Roman gardens

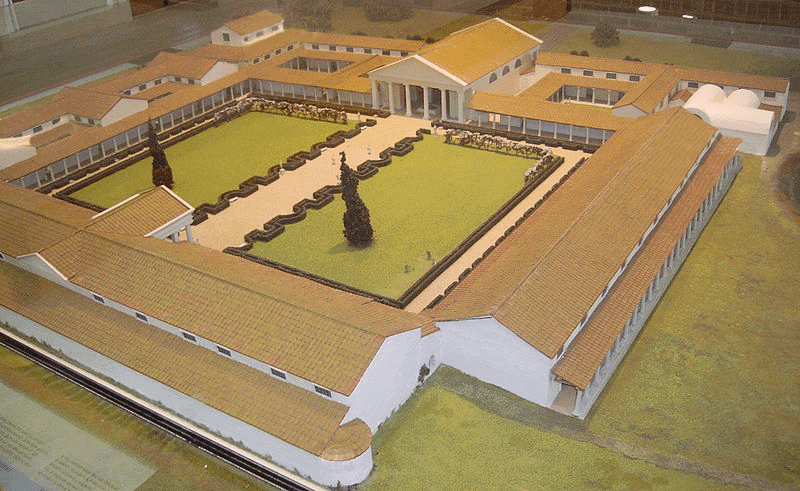

Model of Roman Palace, Fishbourne, West Sussex

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Introduction – Roman Gardens

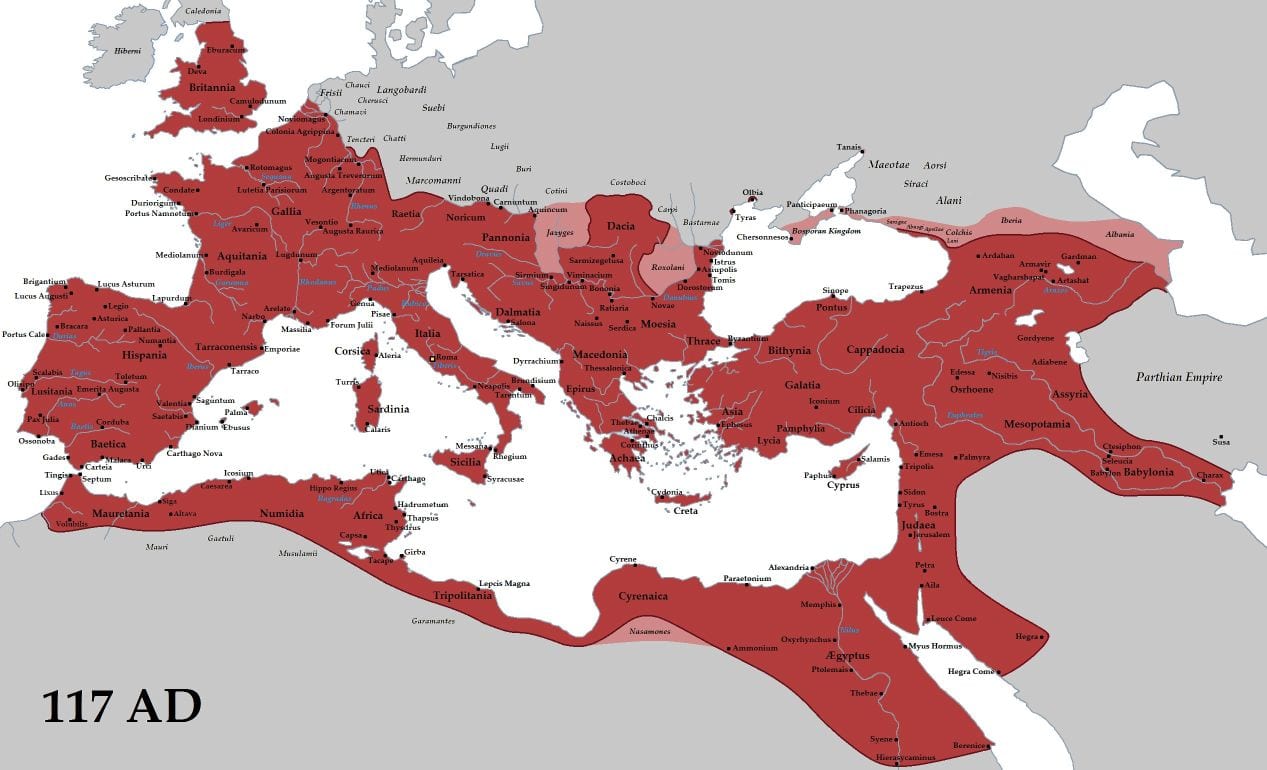

When Roman garrisons crossed the North Sea and occupied Britain in the first century CE, they brought their collective learning about plants and plant management.

The written history of Britain begins with the observations of educated and articulate Roman authors, albeit often biased and distant in time from the events they describe.

Agriculture had taken around 8000 years to be move across Europe from its origins in Mesopotamia, arriving in the British Isles around 4000 BCE. Though British landscapes had been transformed during the British Neolithic Revolution, the other methods of plant husbandry adopted by Romans were alien to Britain’s rustic Celtic tribes.

The plant traditions followed by Roman society had developed out of the Mesopotamian core of civilization as it had developed in the civilizations of the Mediterranean, Near East, and West Asia. These plant practices had proved effective for cities and large populations and they included not only the husbandry of orchards, vineyards, and forests, but also the maintenance of decorative parks, gardens, and avenues of trees. The first gardens, like those we know today, had arisen out of trade, diplomacy, and military conquest in the Bronze Age region of Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Aegean in the third to second millennia BCE.

Rome was, at this time, by far the largest city in the world with well over a million inhabitants. Urban populations like this would only be reached again when London was the hub of its vast British empire in the mid 19th century. The Roman social organization index also indicates a degree of social complexity that would not be attained again until Europe in the 18th century.

Romans had a fully developed agriculture, horticulture, and forestry, all linked to a global economy. To simple Celtic agriculture the Romans added elaborate plant husbandry, introducing more efficient farming technology, novel ornamental plants to decorate gardens, herbs and spices to liven up the bland local food, along with additional domesticated cereals and animals.The modern era of garden design was strongly influenced by the classical gardens that formed part of the of the Italian Renaissance in the 15th and 16th century.

Over the next 2000 years gardening in Britain would inherit reconfigurations of design that were passed across the English Channel from the continent of Europe. With the rise of the British empire Britain would assume its own styles and horticultural traditions to emerge as the world’s greatest gardening nation.

Australian horticulture was a manifestation of British colonialism that harked back to the time when Britain itself had become a north-western colony of the vast Roman Empire.

Emperor Hadrian’s Villa – Tivoli

Remains of the Maritime Theatre dating to c.120-130 CE

Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Historical context

Roman history is divided into two periods: the Roman Republic lasted from 509-27 BCE (Early Republic 458-274 BCE, Middle Republican 274-148 BCE, Late Republic 147-27 BCE), this followed by the Empire which lasted (in the west) from 27 BCE to 476 CE.

Agriculture & horticulture

Though different kinds of plant husbandry had existed for millennia before, it was the Romans who made a firm distinction between agriculture, which used ploughs in fields (agri), and horticulture which used the hoe and digging stick in enclosed spaces called gardens (horti). A feature of both the hortus and main garden was its boundary, clearly defined by a fence or wall, sometimes softened by concealing hedges.

Poet Ovid describes the festival of Terminalia, a celebration of the minor Roman deity Terminus who protected property boundaries. Terminus is reminiscent of Priapus a minor rustic fertility god in Greek mythology who was the protector of livestock, fruit plants, and gardens.

Gardens were attached to private homes, public spaces, shops and inns,[16] the Romans probably being the first to have gardens as essential extensions to their houses[17] although the division between their ornamental and food uses was not always observed.

Agriculture

Romans regarded themselves as farmers by tradition, respecting and celebrating their history on the land. Love of nature and the countryside was sensitively expressed by Cato, Cicero, Catullus, Horace, and Virgil, all praising the enjoyment of retreat (otium) from the onerous duties of civic life (negotium) in a tradition sometimes compared to the peaceful escapism of Greek philosopher Epicurus (see Epucureanism and religion).[30]

Both farms and gardens both changed considerably over the period of Roman ascendancy. In about 500 BC the farms were small and family-owned while at this time there were, in Greece, a few large estates practicing crop rotation. By the late Republic small farms had become absorbed into large country estates called infundibula.

Horticulture

The origin of gardening in the West has been traced to the early settled communities of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Between these early civilizations and the rise of the Roman Empire. the Mediterranean and West Asia (Asia Minor) was a region where countries and empires had waxed and waned, expanded and contracted.

There was early conflict between Egypt and Assyria. In the eastern Mediterranean Persians conquered Babylon and marched west to be met by a Greek army which, under the leadership of Alexander, who fought back, taking all Asia Minor as far as India as a Greek (Hellenistic) empire. had shown not only extraordinary economic and military strength but in absorbing the learning and skills of the ancient world Greek culture marked a culmination of intellectual, scientific and artistic thought. Though the Roman Empire would prevail over all, Roman culture retain its respect for the lifestyle and intellectual brilliance of the culture that it had superceded.

Assyrians and Babylonians were renowned for their parks and hunting reserves a feature of which was the planting of trees. This was admired and emulated by the Persians whose young men were trained in both tree cultivation and the forging of armour.[11] The word ‘Paradise’ is derived from the Greek translation of the Persian word pardes from which we get ‘park’, ‘yard’, and ‘orchard’. Persians conquered Egypt in 525 BC and here they found and copied walled geometric gardens.

Essentially the gardens of the Egyptians, Syrians and Persians were functional, growing mostly food plants, herbs and trees with water to produce shade. With the Romans came heavily designed garden for decorative purposes closely associated with the house, food plants being allocated their own separate area by the kitchen.

Imperial conquests entailed not only plundering and land redistribution but also the reorganization of trading relations along with a realignment of access to resources and ideas. The Roman Empire too would wane but its classical tradition coming from the ancient Mediterranean civilizations would re-emerge during the European Renaissance to remain with us today.

Present-day Greece, the Greek peninsula, had submitted to Roman rule in 146 BC and it is shortly after this time along with the economic success of the empire that Roman gardening thrived, spreading first through Italy and then the Roman Empire. Though the Greeks mounted a brief rebellion the region was finally subjugated by the Roman General Sulla in 88 BCE. About this time Roman gardening reached its peak in the magnificent and luxurious gardens known as the villa urbana, probably modelled on those they had encountered around the Attic residences of wealthy Greek families, themselves influenced by gardens of Persia and elsewhere.

Roman garrisons were a mobile military presence that stimulated the spread of goods and ideas including the introduction of new foods, plants and husbandry techniques, notably the production horticulture used for vegetables, fruits, herbs and nuts now cultivated in market gardens and orchards as cash crops to be sold at market to the military and townsfolk. Roman horticulture had borrowed ideas and traditions from Egypt, Persia (Iran), and the Hellenistic world. From these sources it forged the foundations of the gardening we all know today. Garden history authority Edward Hyams says of the Romans. ‘Their gardens, like their architecture and sculpture and engineering, they owed to the Greeks.’[10] But he adds that as Romans were conscientious students with access to money and labour they were soon constructing gardens that excelled those of their Greek mentors. It was a gardening tradition that was strongly linked to architectural and artistic style, social structure and lifestyle – remembering that the story of Roman gardens like the story of most of early garden history, an account of the traditions of a wealthy class.

Pliny the Elder credits the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341 –270 BCE) as introducing the idea of the pleasure garden, the wealthy Romans also using their gardens as leisurely retreats from the demands of business and public life, although with the increasing wealth of the late Republic of the first century CE empire the pleasure garden changed from being a humble place for simple pleasures into an opportunity for displaying luxury and extravagance.

Roman gardening appears to have been pursued with great passion, culminating at about the time of the author Pliny the Younger (c.61 -112 CE) at the time of the Late Republic when such gardens were found on the periphery of cities combining the benefits of city (urbs) and country (rus). By this time both the literature of the day and archaeological remains attest to many garden elements that are familiar today including: design using hard landscape and elaborate sculpture; use of roses, lawns, topiary and trimmed box hedging and cypresses; hothouses; indoor and outdoor fountains; baths; fish pools; solariums; arbours; dovecots; outside dining areas; trellised pergolas; roof gardens; grottoes. Among the popular plants were: plane trees and sycamore for public parks, cypresses, oak, pine and spruce, but also mulberries, figs, bay (Laurus nobilis) and myrtle (Myrtus communis), and for ground cover ivy, ferns and periwinkle (Vinca major). Other luxurious tuches included painted murals and exotic and entertaining fauna including song-birds and peacocks. Pliny mentions 12 varieties of rose as well as various bulbs and violets.

Romans brought horticultural practices and plants from the Mediterranean and introduced new breeds of farm animals like the prized white cattle, Guinea fowl, chickens – and game that included the Brown hare and pheasants. Oxen and mules did the heavy work on the farm. Sheep and goats were cheese producers, and were prized for their hides. Horses were not widely used in farming, but were raised by the rich for racing or war. There was beekeeping for honey and some Romans raised snails as luxury food (Helix pomatia, Burgundy Snail or Roman Snail, not the Common garden Snail Helix aspera).

Today relatively few Roman gardens still remain, with the notable exception of those of Pompei, Herculaneum, and Stabies, preserved in the larva that flowed from the eruption of Mt Vesuvius in 79 CE. Another notable exception is the villa of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 CE) at Tivoli (figured at the head of this page), although we have detailed descriptions of magnificent gardens constructed when Rome was at its height. No archaeological evidence of Roman gardens was found in Britain until the 1960s when sites were located at Frocester Court, Gloucestershire, and then at Fishbourne, Sussex. Pompeian houses and their dining rooms and even tomb walls displayed wall paintings of garden scenes that included conifers, oak trees, quince, pomegranate, palms, laurels, oleanders and plane trees and the flowers roses, chrysanthemums, daisies, poppies, lilies and violets.[15] In about 90 BC there is some evidence of villa gardens dating from the end of the second century BC and of their rapid increase in numbers in both town and country, also along the east coast facing the Tyrrhenian Sea, and at the mouth of the Tiber. They were soon to spread throughout Italy and the Roman Empire from Syria and Islamic countries in the East to Britain in the west.[12]

From the earliest times plants were collected as trophies of travel and military campaigns. ‘ … aristocratic Roman Generals returning from their military campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean were interested in exotic trees and garden plants, and they brought back such specimens as the cherry, the peach, the apricot, and the pistachio for the public parks and their own villas … ‘[1] Pliny the Elder in his Natural History notes that the cherry was introduced to Rome in the early 1st century BC finding its way to Britain 120 years later.[2]

Greek influence

Greek culture left its influence on plant science through the work of Theophrastus who succeeded Aristotle as head of the Lyceum in ancient Athens. He left what were, in effect, the world’s first two textbooks on botany. The Romans were practical, their interests reflecting the farming that underpinned the Roman economy. They added little to the collective knowledge of Greek science but they both admired, and embellished, the Hellenistic garden tradition.

From these historical sources wealthy Romans forged the foundations of the gardening that we have inherited today. Garden historian Edward Hyams notes of the Romans: ‘Their gardens, like their architecture and sculpture and engineering, they owed to the Greeks’ adding that as conscientious students with access to money and labour, Romans were soon constructing gardens that excelled those of their Greek mentors.[2]

The Greeks of course had their own influences. Theirs was a gardening tradition with architectural and artistic style produced by a social class that intended to compete and impress. We know about Roman gardens from both their archaeological remains and a written record of several generations of highly articulate Roman authors.

Pliny the Elder credits the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341 –270 BCE) with the introduction of the idea of the pleasure garden, the wealthy Romans also using their gardens as leisurely retreats from the demands of business and public life, although with the increasing wealth of the late Republic of the first century CE empire the pleasure garden changed from being a humble place for simple pleasures into an opportunity for displaying luxury and extravagance.

Roman villa gardens created a strong sense of space through the use of hedges, clipped three-dimensional shapes, and sculptures, as well as exploring the natural colour and form of the plants. There was the origination of plant cultivars, both ornamental and fruits and the control of growth through topiary, pruning, pollarding (chamaeplatanus) and training on structures; the forcing of plants in rudimentary glasshouses, all of which appear in the early Imperial era. These crude conservatories and hot-houses are first mentioned by Martial (VIII.14, 68, IV.19, XIII.127) as places to preserve foreign plants and to produce flowers and fruit out of season. Columella (XI.3§§51, 52) and Pliny (H.N.XIX.5s23) speak of forcing-houses for grapes, melons,&c. and in every garden there was a space set apart for vegetables (olera).[37] It explored the themes of culture (cultura) and nature (natura) present through most of garden history.

Romans were keen gardeners and accomplished at topiary especially with box hedges (Buxus) and at forcing flowers and fruits to bloom and mature outside the natural season.[14] Pliny the Elder remarks ‘nowadays the cypress is clipped and made into thick walls‘ and ‘trimmed shrubberies were invented within the last 80 years by a member of the Equestrian order named C. Matius, a friend of the late Augustus’[16]

Plants were forced to mature out of season by exposing them to heat in a controlled environment. Pliny the Elder describes how emperor Tiberius (42 BCE-32CE, ruled 14-37 CE) was provided year-round with ‘cucumbers’ by growing them in wheeled carts brought indoors at night and placed during the day in forcing houses which we can regard as precursors to our ‘greenhouses’: they were constructed of either oiled cloth (specularia) or thin sheets of cast glass (selenite or mica) and called lapis specularis, vitrum, gemma or just specularium , one known site of use being Tiberius’s villa on the isle of Capri. Warmth was also maintained by the use of animal dung. Later Roman emperors improved on the original designs, using more elaborate constructions for growing grapes and roses.[33]

A professional gardener-designer was called a topiarius (pl. topiarii). We know about them mostly from epitaphs written in the first century CE which indicate their social status and where they worked, some 50 being recorded as working for royal or influential families. Some were members of collegia which were like guilds or clubs of people with common interests, and some were clearly serving as apprentices (discentes).[32]

The first century CE was a period of plant exchange, ideas and experimentation when, for example, records of figurative topiary occur in the literature, Pliny referring to the clipping of cypress so that it ‘ … is even made to provide representations of ornamental gardening, depicting hunting scenes or fleets of ships and imitations of real objects’(HN 16.140).

Literature

Most Roman literature on plants was dedicated to agriculture, notably three major treatises, all called De Agricultura (On Agriculture) and written by: Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE), Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BCE), and Junius Moderatus Columella (fl.60-65 CE, who lived in Cadiz, southern Spain). Roman agricultural writer Palladius of the mid 5th century wrote authoritatively on agriculture and it was his work especially that served as a respected text across Europe in the Middle Ages. In 146 BCE Rome had sacked the city of Carthage, some of the contents of its libraries eventually finding their way to Rome. Among these were 28 books written on agriculture by Carthaginian Mago, written in the Punic language. Most were lost but some translated first into Greek and then Latin (as De Re Rustica).

Almost all the Roman literature relating to plants is to do with agriculture, there being three major treatises titled On Agriculture by Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE), Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BCE), and Junius Moderatus Columella (fl.60-65 CE) who lived in Cadiz (southern Spain).

Cato the Elder was a politician and statesman in the mid-to-late Roman Republic. His account, written c. 160 BCE, was the first and most respected by Roman writers, he recognised several farm components: the vineyard, irrigated garden, willow plantation, olive orchard, meadow, grain land, forest trees, vineyard trained on trees, and lastly acorn woodlands. Cato’s description of a Roman farm of size 100 iugera (4 iugera = 1 ha) gives an idea of the sophistication of Roman agriculture and the farm management techniques at this time.

A farm of 25 ha should have ‘a foreman, a foreman’s wife, ten labourers, one ox driver, one donkey driver, one man in charge of the willow grove, one swineherd, in all sixteen persons; two oxen, two asses for wagon work, one ass for the mill work’ and in addition there should be ‘three presses fully equipped, storage jars in which five vintages amounting to eight hundred cullei can be stored, twenty storage jars for wine-press refuse, twenty for grain, separate coverings for the jars, six fibre-covered half amphorae, four fibre-covered amphorae, two funnels, three basketwork strainers, [and] three strainers to dip up the flower, ten jars for [handling] the wine juice …[3]

Cato, in his writing, draws attention to the fact that the labour needed to run large productive country estates was provided by slaves with Roman overseers.

New cultivars included the soft wheats (Triticum aestivum) were introduced to Roman agriculture as Roman dominions spread Eastwards around the time of Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great. The new wheat required less work to mass-produce flour and facilitated a greater variety of breads and cakes than the traditional ’farr’ or Spelt (Triticum Spelta – rugged wheat). Fruits like peaches and lemons were also introduced at this time (see Roman gardens).

Careful breeding of cows, pigs and sheep with improved supplies of winter crops improved the quantity and quality of meat and dairy productsGardens are mentioned briefly by poets like Ovid, Propertius, and Martial. Mention of gardens is brief but can be found in works by Palladius (late 4th century CE), the Natural History of Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE)[25] and a few references to gardens in the Georgics of poet Virgil (70-19 BCE). Only Columella and Palladius provide extended commentary on gardens. With few physical remains of Roman gardens accounts of garden detail rely heavily on the few remaining wall frescoes and accounts written by the Romans themselves. Almost all this literature is devoted to agriculture the most notable being three major treatises called On Agriculture: Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE), Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BCE), and Junius Moderatus Columella (fl.60-65 CE) who lived in Cadiz (southern Spain). Writings including mention of gardens are by Palladius (late 4th century CE), the Natural History of Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) and in the Georgics of Virgil (70-19 BCE). However, it is only Columella and Palladius who provide extended commentary on gardens, while the letters of Pliny the Younger (c. 62-113 CE) provide some descriptions of famous parks and gardens in the introduction to Book 9 of his Naturalis Historia. In Columella’s 12 volume work On Agriculture it is only in book 10 that the subject turns to gardens (cultus hortorum) expressed as a poem conceived as a supplement to the Georgics of Virgil.[13] Varro gives a list of over 50 Greek treatises on agriculture but no such treatises on gardening survive and, indeed, may never ave been written although there is no doubt that gardening was practised.[14] It is to the Greeks that we must first turn to see how they influenced the Romans.

The letters of Pliny the Younger (c. 62-113 CE) provide some descriptions of famous parks and gardens in the introduction to Book 9 of his Naturalis Historia. Columella’s account of agriculture runs to 12 volumes but it is only in Book 10 that he turns to gardens (cultus hortorum) written as a poem conceived as a supplement to the Georgics of Virgil.[7] Varro, in his work, cites over 50 Greek treatises on agriculture but none survive and it is possible they were never written.[8]

Pliny the Elder devotes 16 of the 37 encyclopaedic books comprising the Naturalis Historia to plants, mostly their medicinal uses but with some advice on cultivation. Sadly Gargilias Martialis’s third century work De Hortis has not survived, a single remaining fragment on arboriculture suggesting an acute mind.[19]

Greek bard Homer’s fictional garden of King Alcinous was probably the inspiration for Roman poet Virgil’s (70-19 BCE) poem Hortus in the Georgics.[22] Here Virgil compares the simple pleasures of a country farmer to the luxury estates of kings, the prose evoking a Mediterranean vision of the satisfaction reaped by the honest toil of a man working in harmony with the seasons. We can hear Homer’s influence on the work of the English Romantic poets like Keats and their idealisations of pastoral bliss that were produced some two millennia later:

‘… I saw an old Corycian, who had a few acres of unclaimed land and this, a soil not rich enough for bullocks ploughing, unfitted for the flock and unkindly to the vine. Yet, as he planted herbs here and there among the bushes, with white lilies about, and vervain, and the slender poppy, he matched in contentment the wealth of kings, and returning home in the late evening, would load his boards with unbought dainties. He was the first to pick roses in spring and apples in autumn; and when sullen winter was still cracking rocks with cold, and curbing running waters with ice, he was already culling the soft hyacinth’s bloom, reproaching laggard summer and the loitering zephyrs. So he, too, was the first to be enriched by mother-bees and a plenteous swarm, the first to gather frothing honey from the squeezed comb. Luxuriant were his limes and wild laurels and all the fruits his bounteous tree donned in its early bloom, full as many it kept in the ripeness of autumn. He, too, planted out in rows elms far-grown, pear trees when quite hard, thorns even now bearing plums, and the plane already yielding to drinkers the service of its shade.

Virgil, Georgics 4.125-146

With few physical remains we must build up a picture of the Roman garden through the evidence of wall frescoes and accounts written by the Romans themselves. Respected politicial and commentator Cicero (106-43 BCE, also known as Tully), perhaps more than any other Latin writer, sets the scene for us, making general reference to gardens as desirable possessions and an appropriate vehicle for the demonstration of taste, learning or, when carried to excess, of dissipation and decadence.[21] Indeed, disapproving chroniclers are not hard to find. Both the influential statesman and dramatist Seneca the Younger (4 BCE-65CE) and his literary father Seneca the Elder (54 BCE-39 CE) regarded large-scale villas and elaborate designs as excessive luxuria, Seneca the Younger deriding the opulent villa of the politician Vatia as an escape from the responsibilities of life. On occasion grumbling was assuaged when wealthy owners bequeathed their land to the people of Rome.

The classic description of an outstanding Roman garden appears in a letter of the younger Pliny, in which he describes his Tuscan villa (Plin. Epist.V.6). In front of the porticus there was a xystus, or flat piece of ground, divided into flower-beds of different shapes by borders of box. There were flower-beds elsewhere, sometimes raised to form terraces, their sides planted with evergreens or creepers. Most striking were the avenues of large trees, the plane being the most popular along walkways (ambulationes) formed by clipped hedges of box, yew, cypress, and other evergreens; beds of acanthus, rows of fruit-trees, especially of vines, with statues, pyramids, fountains, and summer-houses (diaetae). Structures were covered with ivy (Plin.l.c.; Cic. adQ.F.III.1, 2). Topiary (ars topiaria) was especially popular as indicated by the use of the word topiarius for the gardener. Cicero (Parad.V.2) regarded the topiarius among the higher class of slaves.[37]

Prolific author, lawyer and civic dignitary Pliny the Younger (61-112 CE) lived at a time when great wealth was channelled into private estates where plants and structures were combined to form a vision of perfected nature: his own villas in the Apennine mountains (the Tusci) and his estate called Laurentinum of the coast near the port of Ostia outside Rome, give us insight into this period[3] and descriptions of his magnificent villas (the Tusculan villa had two gymnasia called, following th Greeks, the Lyceum and Academy) would be a source of inspiration during the Italian Renaissance much later when the association of gardens with men of learning and sensitivity was continued through leading social figures like Lorenzo di Medici whose garden, called the Academy, was constructed in 1439 in Careggi just outside Florence.[20][27] Pliny famosly connected gardens to landscape painting describing his Tuscan garden as ‘not a real, but some painted landscape, drawn with the most exquisite beauty and exactness’.

There is only one formal account of architecture and design in the Roman world, De Architectura Libri Decem[1] (Ten Books of Architecture) by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (75-15 BCE). Better known simply as Vitruvius, this soldier in the army of Julius Caesar gives us the only insight into the architectural brilliance of the Romans and, sadly, his compendium contains little reference to gardens and designed landscapes. Even so, from this work can be gleaned the preferred Roman terminology for parks and gardens: hortus as a vegetable or market garden); paradeisos, for park; silvae, for a luxury plantation; topia, both topiary as we know it today, but especially landscape gardening; viridia, a formal display of plants, often exotic and skilfully pruned and curated (viridarium, a collection of viridia); within architectural elements were walkways known as ambulationes and xysti.[2] By 100 CE the word viridia referred specifically to specially clipped evergreen trees and shrubs.[15] Apellations herbularius and hortus medicus, denoting a herb garden (hortulanus was a later term), are probable Medieval additions.

Associated with the more extravagant gardens were places for exercise, the gestatio and hippodromus. The gestatio was a sort of avenue, shaded by trees, for the purpose of taking gentle exercise (Plin. Epist. V.6, II.17). The hippodromus was a place for horse exercise with several paths divided by hedges of box, ornamented with topiarian work, and surrounded by large trees (Plin.,l.c.; Martial, XII.50, LVII.23). An ornamental garden was also called viridarium, the gardener a topiarius or viridarius or, more commonly the villicus or cultor hortorum. The aquarius had charge of the fountains both in the garden and in the house (Becker, Gallus, vol.I p283, &c.; Böttiger, Racemationen zur Garten-Kunst der Alten).[37]

Hortus to Villa Urbana

During the Early Republic (458-274 BC) and Middle Republic (274-148 BC) the average Roman citizen’s smallholding consisted of a fruit and vegetable garden with herbs – what we would now call a kitchen garden or, if larger and more productive, a small market garden. This was generally protected from animals by a wall and situated at the back of the house close to the kitchen. The Romans called it a hortus. It is clear that, like today, the hortus proved labour intensive for meager results.

Villa Rustica

In about 90 BCE there is some evidence of villa gardens dating from the end of the second century BCE and of their rapid increase in numbers in both town and country, also along the east coast facing the Tyrrhenian Sea, and at the mouth of the Tiber. These were soon to spread throughout Italy and the Roman Empire from Syria and Islamic countries in the East to Britain in the west.[4]

Towards the end of the Late Republican period these gardens had become large and elaborate with formal parterres, long avenues of trees and vast lakes with associated parkland stocked with game for the recreational hunting forays of landowner and guests. It is not possible to ignore the parallel between this and the English country estate of the landed aristocracy and gentry. However, this was still essentially gardening within a hard landscape, the architecture defining the space. There were also garden eating areas, taverns, and pavilions.

The villa rustica of the Late Republican period (147-30 BC) was more like an estate with a vineyard and some domestic animals for dairy products.

Villa Urbana

Town houses or villa urbana were characterised by a smallish courtyard-like gardens surrounded by architecture which had, in addition, decorative plants.

With Late Republican politician, orator, lawyer and philosopher Cicero (106-43 BC) the grand Roman garden emerges as a gymnasium combined with the villa urbana to include lawns, grass, statuary, trees (mostly cypresses and planes), vine and rose pergolas, trellises, arbours, also grottos and elaborately constructed irrigation and water features which included elaborate fountains in the more opulent gardens. Their conceptual basis was essentially the Greek nymphaeum. Terraced hillside gardens were reminiscent of the ziggurats of Mesopotamia, possibly even the Hanging Garden of Babylon, with staircases alongside waterfalls with, at their base, a grove of trees with seats in the shade, the whole area surrounded by clipped hedges.

Towards the end of the Late Republican period these gardens had become even more ornate, spacious and artistic with formal parterres, long avenues of trees and vast lakes, even garden eating areas, taverns, and pavilions all with an associated parkland stocked with game for the recreational hunting forays of landowner and guests, emulating the Persian Paradeisos. For example, Gaius Maecenas (c. 70 – 8 BCE) was a friend and political advisor to Octavian, later Augustus, also an important patron for a generation of Augustan poets that included both Horace and Virgil. During the reign of Augustus, he served as a quasi-culture minister but chose not to enter the Senate, remaining of equestrian rank. His famous gardens on the Esquiline Hill in Rome were the first constructed in the Hellenistic-Persian garden style astride the Servian Wall and its adjoining necropolis, near the gardens of Lamia. It contained terraces, libraries and other artefacts of Roman culture. He was possibly the first to construct a hot water swimming bath in Rome, possibly within the gardens. The flagrant opulence of his gardens and villas was resentfully recorded by Seneca the Younger. The Auditorium of Maecenas, a probable venue for dining and entertainment, may still be visited upon reservation. When Maecenas died the gardens became imperial property and were occupied by Tiberius lived when returning to Rome in 2 CE.

Villa gardens of Imperial Rome appear to display a new approach to that of the earlier Egyptians, Persians and Assyrians. The Mesopotamian gardens, though attractive had retained functionality with many of the plantings being used for food. With the Romans gardening became a passion of the social elite, the ‘pleasure’ garden and its decorative qualities became paramount, the garden strongly associated with the house through colonnades and statuary, the herbs, fruit trees and vegetables often being assigned to a separate and distinct area. The steady supply of water needed for pools and fountains, a feature of the peristyle garden (a colonnaded surround to an internal courtyard garden) could only be accessed by the wealthy. Courtyards like these were used for open-air dining, a popular Roman domestic past-time with the three-seated couch or triclinium which permitted refreshment in a semi-reclining position. There were art objects like sculptures of animals and deities. Painted walls extended the boundaries of the garden, plants and other trophies of war were displayed in the gardens of military men and bathing pools were also included. Flowers would be used to decorate the family shrine and for celebrations and festivals.

Here we can see a model for later European styles including the English country estate of the landed aristocracy and gentry. However, this was still essentially gardening within a hard landscape, the architecture defining the space.

Parks & public space

Vast parks were established, the emperor Nero in 64 CE constructing a landscaped park with a lake, woodland, pasture, and vineyards. Plane trees were popular avenue subjects with welcome shade for drinkers as poet Virgil tells us.[29] At its height Rome possessed some 70 city and villa parks with luxury villas (domus) on the outskirts of the city or in the surrounding hills. Some had extensive grounds, like the Domus Augustana on the Palatine Hill which boasted a hippodrome and the most, but probably the best known was the Domus Aurea of Emperor Nero.

Roman art

In the absence of extensive garden archaeology, much of what we know about Roman attitudes to plants comes to us from written and pictorial sources like wall frescoes.

Landscape painting

The origin of landscape painting is contentious. Landscapes were painted in Minoan buildings of the Aegean islands of Crete and Santorini (Thera) with its Bronze Age settlement of Akrotiri, and Milos in the second millennium BCE. Roman authors Vitruvius and Pliny refer to Studius as the first artist to specialise in landscape painting (opera topiaria) in the first century BCE[24] although frescos from Minoan Crete dating to c. 1500 BCE depict landscapes without human presence as do some Egyptian paintings, albeit without the same ‘atmosphere’. The first surviving painting of a Roman garden covers the walls of a hall in the villa of emperor Augustus’s wife Livia in Prima Porta north of Rome although they have been found in other villas too. Many examples of garden paintings survive from the Roman period that show Etruscan, Persian and Greek influences, often combining elements of both garden and the wider landscape.[24] By the early empire following the increase in wealth and cosmopolitanism greater space was devoted to gardens and more care taken with the placement of sculptures (as mythic and historic figures and often imported from Greece), buildings and monuments.

Pliny the Younger makes the comparison between art and nature when viewing the scenery from his Tuscan villa ‘It is a great pleasure to look down on the countryside from the mountain, for the view seems to be a painted scene of unusual beauty rather than a real landscape, and the harmony to be found in this variety refreshes the eye wherever it turns’ indicating the reciprocity of art and nature that has been so important in the history of garden design.(Ep. 5.6.13) [cited in Cook & Foulk, p.188] Statuesque Stone Pines (Pinus pinea, source of edible pine nuts) with their umbrella-shaped canopies were grown on the hills.

By the late first century BCE landscape painting had been incorporated in murals and ceiling stuccoes, in corridors, dining areas, and bedrooms. Garden murals decorated the enclosed space of the viridaria. Clearly villas were built and designed to take advantage of views and vistas.[23]

Pompeian houses and their dining rooms and even tomb walls displayed wall paintings of garden scenes that included conifers, oak trees, quince, pomegranate, palms, laurels, oleanders and plane trees and the flowers roses, chrysanthemums, daisies, poppies, lilies and violets.[3] Varro offered advice on the popular commercial rose-growing which was centred in Paestum.[36]

Mosaics

The use of mosaics tiling associated with Roman villas had developed earlier in Greece and North Africa[34], they were used to decorate both floors and ceilings especially in the Late Republican and Early Empire periods when they could also be seen decorating grottos, nymphaea, musaea, and water shrines with vegetation motifs, the mosaics often incorporating pumice, marine shells and Egyptian glass.[35]

Garden innovation

The complexity of Roman social organization is reflected in its capacity to both maintain established traditions and to provide innovations as increased efficiencies and ideas. It is difficult to know when, precisely, new ideas and technologies arose as change often comes from established tradition, however insignificant, but the following is a suggested list of Roman contributions to the history of gardens and horticulture:

Roses, grown as prized ornamental plants, date back to ancient Egypt. Their special favour across Europe – including their intensive breeding in France and Britain, and no doubt stimulated by the extensive collection accumulated by Josephine Bonaparte at her Malmaison retreat – owes its origins to the love of ancient Romans for this flower, which they celebrated each year from May to June in a festival of roses (Rosaria).

Plant introduction

Among the garden plant genera mentioned by Latin writers are the trees: – Cupressus (Cypress), Populus (Poplar), Salix (Willow), Ulmus (Elm), Fraxinus (Ash), Laurus (Bay), Picea (Spruce), Pinus (Pine), and Platanus (Plane). Fruits included Arbutus, Citrus, Ficus (Fig), Lotus, Morus (Mulberry) ?Tubur, Ziziphus. Shrubs and flowers – Acanthus, Adianthus, Buxus, Cynoglossum, Hedera, Jovis-barba, Lilium, Myrtus, Rhododendron, Rosa, Rosmarinus, Viciapervica, and Viola.[13, for example] Violets were used in garlands, although ‘violet’ referred to plants other than those in the genus Viola.

Lucius Lucullus (118 – 57/56 BCE) is credited with introducing the cherry, peach and apricot via his campaigns in the East – the apricot from today’s armenia, and peach from Persia. Specimens and knowledge of the plants were probably obtained from Mithridates VI (134–63 BCE) of Pontus (near the Black Sea). Mithridates ruled over most of the Parthian Empire (essentially ancient Persia). His court physician and herbalist Crateuas (fl. 120-60 BCE) published a respected alphabetical list of medicinal plant descriptions as well as botanically accurate painted illustrations . . . and, in so doing, made a pioneering contribution to the discipline of botanical art. Cherries found their way to Britain 120 years later.[6]

Other flowers included crocus, narcissus, lily, gladiolus, iris, poppy, and amaranth.

The modern era of garden design was strongly influenced by the classical gardens that formed part of the Italian Renaissance period in the 15th and 16th century.

From the earliest times plants were collected as trophies of travel and military campaigns. ‘ . . . aristocratic Roman Generals returning from their military campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean were interested in exotic trees and garden plants, and they brought back such specimens as the cherry, the peach, the apricot, and the pistachio for the public parks and their own villas . . . ‘[5]

Pliny mentions the horseman (eques) Corellius developing a new variety of the chestnut ‘Corelliana’ (HN 17.122) and Allenius imported the azarole and Ziziphus from Italy, also different cultivars of myrtle (HN15.122)

Pliny also refers to the importation of the Plane tree (Platanus orientalis) for its shade and that it is the most frequently mentioned tree in Roman literature being cultivated around the Mediterranean, even in a dwarf form produced by pollarding (chamaeplatanus).(HN15.122).[31] Regardless of warnings from Dioscorides and Galen that the plane affected breathing and the lungs (this was probably from the fine hair associated with the fruit) the tree had been introduced to Italy from Greece proving popular in both public space and private gardens.[30]

In a review of archaeobotanical records in Britain from this period[11] it was found that prior to Roman occupation there had been a few plant introductions in the Late Iron Age (along with preserved foods like wine and olive oil), and the introduction of wheat and barley in the Neolithic. With the arrival of the Romans there was a rapid introduction of about 50 new plants, mostly fruits, herbs and spices, and vegetables, extending the flavours and nutrient content of the traditional food palette. Most of these new plants grew naturally around the Mediterranean but some were the result of trade in more distant lands – like black pepper from India, dates from the Near East and North Africa. It is not possibly to distinguish domesticated variants (cultivars) from the seed in archaeological deposits although they probably existed. The pernicious ground elder, Aegopodium podagraria, is believed to have been introduced to Britain by the Romans as a salad crop.

| Botanical name | Common name | Status | Naturalised in Australia |

| Cereals | |||

| Panicum miliaceum | Millet | * | |

| Triticum monococcum | Einkorn | ||

| Pulses | |||

| Lens culinaris | Lentil | ||

| Vicia ervilia | Bitter Veitch | ||

| Fruits | |||

| Ficus carica | Fig | * | |

| Vitis vinifera | Grape | ||

| Morus nigra | Mulberry | * | |

| Olea europaea | Olive | * | |

| Persica vulgaris | Peach | * | |

| Phoenix dactylifera | Date | * | |

| Punica granatum | Pomegranate | * | |

| Malus spp. & cvs | Apples | * | |

| Pyrus spp. & cvs | Pears | * | |

| Prunus avium | Sweet Cherry | * | |

| Prunus cerasus | Sour Cherry | * | |

| Prunus cerasifera | Cherry Plum | * | |

| Prunus domestica subsp. domestica | Plum | * | |

| Prunus domestica subsp. insititia | Damson | * | |

| Vegetables | |||

| Beta vulgaris | Leaf Beet | * | |

| Brassica napus | Rape | * | |

| Brassica oleracea | Cabbage | * | |

| Brassica rapa | Turnip | * | |

| Allium porrum | Leek | * | |

| Cucumis sativus | Cucumber | ||

| Daucus carota | Carrot | * | |

| Pastinaca sativa | Parsnip | * | |

| Lactuca sativa | Lettuce | ||

| Asparagus officinalis | Asparagus | * | |

| Condiments | |||

| Piper nigrum | Black Pepper | ||

| Coriandrum sativum | Coriander | * | |

| Anethum graveolens | Dill | * | |

| Apium graveolens | Celery | * | |

| Foeniculum vulgare | Fennel | * | |

| Petroselinum crispum | Parsley | * | |

| Pimpinella anisum | Anise | ||

| Satureja hortensis | Summer Savoury | ||

| Origanum vulgare | Marjorum | ||

| Mentha spp. & ? cvs | Mint | * | |

| Marrubium vulgare | Horehound | * | |

| Nigella sativa | Black Cumin | ||

| Ruta graveolens | Rue | ||

| Sinapis alba | White Mustard | * | |

| Levisticum officinale | Lovage | ||

| Oil seeds | |||

| Sesamum indicum | Sesame | * | |

| Camelina sativa | Gold of Pleasure | * | |

| Cannabis sativa | Hemp | * | |

| Papaver somniferum | Opium Poppy | * | |

| Brassica nigra | Black mustard | * | |

| Nuts | |||

| Juglans regia | Walnut | ||

| Pinus pinea | Pine Nut | ||

| Amygdalus communis | Almond | ||

| Castanea sativa | Chestnut | ||

| Other | |||

| Humulus lupulus | Hop | * | |

| Buxus sempervirens | Box |

New breeds of farm animals were introduced, like the prized white cattle, Guinea fowl, chickens – and game that included the Brown hare and pheasants. Oxen and mules did the heavy work on the farm. Sheep and goats were cheese producers, and were prized for their hides. Horses were not widely used in farming, but were raised by the rich for racing or war. There was beekeeping for honey and some Romans raised snails as luxury food (Helix pomatia, Burgundy Snail or Roman Snail, not the Common garden Snail Helix aspera).

Plant introductions to Britain

It is likely that many of the Mediterranean culinary herbs and food plants now growing in the temperate and warm climate British colonies and Neo-Europes (like North America, Australia, and New Zealand) originated from Britain.

We know the Romans used plants and flowers for many purposes. Apart from flavourings and food they were used for decoration, religious rites, medicine, making honey, garlands, and perfume and that many of these were brought with them to Britain. There were changes in popularity of various herbs over time and the attribution of Roman introduction of a number of garden plants has been challenged but the following working list gives us a general idea of Roman plant introduction. It is sourced from New Plant Foods in Roman Britain — Dispersal and Social Access by Marijke van der Veen, Alexandra Livarda and Alistair Hill (available as a pdf online).

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

Villa gardens of Imperial Rome display a new approach from that of the earlier Egyptians, Persians and Assyrians. The Mesopotamian gardens, though highly attractive, had retained functionality with many of the plantings being used for food. With the Romans gardening became a passion of the social elite, the ‘pleasure’ garden and its decorative qualities became paramount, the garden strongly associated with the house through colonnades and statuary, the herbs, fruit trees and vegetables often being assigned to a separate and distinct area.

The steady supply of water needed for pools and fountains, a feature of the peristyle garden (a colonnaded surround to an internal courtyard garden) could only be accessed by the wealthy. Courtyards like these were used for open-air dining, a popular Roman domestic past-time with the three-seated couch or triclinium which permitted refreshment in a semi-reclining position.

Flowers and plants were also a feature of the central space in a peristyle garden. Frescoes often features gardens where these could not be grown, and they included trees, fountains, birds, &c (Gell’s Pompeiana, II.4). There were art objects like sculptures of animals and deities. Painted walls extended the boundaries of the garden, plants and other trophies of war were displayed in the gardens of military men and bathing pools were also included. Flowers would be used to decorate the family shrine and for celebrations and festivals, they would appear as decoration on jewellery, pottery, household objects and elsewhere. Acanthus, ivy and grape vines were a decorative motif for sculptures and architecture. Shady trees now framed public meeting places of all kinds.

Roman gardening appears to have been pursued with great passion, culminating at about the time of the author Pliny the Younger (c.61 -112 CE) at the time of the Late Republic when such gardens were found on the periphery of cities and therefore combining the benefits of city (urbs) and country (rus). By this time both the literature of the day and archaeological remains attest to the many garden elements that are familiar to us today including: design using hard landscape and elaborate sculpture; use of roses, lawns, topiary and trimmed box hedging and cypresses; hothouses; indoor and outdoor fountains; baths; fish pools; solariums; arbours; dovecots; outside dining areas; trellised pergolas; roof gardens; grottoes. Among the popular plants were: plane trees and sycamore for public parks, cypresses, oak, pine and spruce, but also mulberries, figs (many varieties), bay (Laurus nobilis) and myrtle (Myrtus communis), and for ground cover ivy, ferns and periwinkle (Vinca major). Other luxurious tuches included painted murals and exotic and entertaining fauna including song-birds and peacocks. Pliny mentions 12 varieties of rose as well as various bulbs and violets.

In the reconstruction that followed Rome’s great fire of 64 CE emperor Nero constructed a vast and luxurious Domus Aurea (Golden House) in the valley between the Esquiline, Palatine and Caelian hills criticised for its decadence by historians Tacitus and Suetonius who described its opulent architecture, woodlands, vineyards, artificial lake simulating the sea, magnificent vistas and even ploughed fields, domestic animals and wild beasts. Criticism was directed not only at the material extravagance but also the artistic audacity of trying to ‘better’ nature within the urban environment (rus in urbe), Suetonius making a clear distinction between wild (ferarem) and domestic (pecudum) animals, and differentiating natural and cultivated spaces and the inappropriateness of a transplanted landscape.[Cook & Foulk, p. 192]

By 155 CE Rome was enjoying the spoils of its empire. Romans as cultivators of gardens, landscapes and men is aptly expressed through a panegyric by Aristides called Regarding Rome which declares (in part):

’Everything is full of gymnasiums, fountains, gateways, temples, handicrafts and schools … Indeed the cities shine with radiance and grace, and the whole earth has been adorned like a pleasure garden.’ Aristides goes on to praise the garden as not only a place of pleasure and learning but also as a mark of civilization, and then expands his horizon to the landscape as a whole by claiming that when Homer declared ‘The earth was common to all’ Rome had made this a reality ‘… by surveying the whole inhabited world, by bridging the rivers in various ways, by cutting carriage roads through the mountains, by filling desert places with post stations, and by civilizing everything with your way of life and good order. Therefore I conceive of life before your time as the life thought to exist before Triptolemus,[17] harsh, rustic, and little different from living on a mountain …’[18]

What have the Romans ever done for us?

Gardening, along with all the basic gardening tools,[28] was introduced to Britain by the Romans.

A quick glance down an Australian suburban street at the design confusion of the diverse array of picket and other fences, walls and hedges, all so different from one-another, shows us how deep-seated is the need for surrounding boundaries and limits that define our territory, declare ownership, and maintain order in social space. Here the Roman god Terminus is alive and well, giving us each a physical space where we can be law-abider or transgressor.[16]

Most of the non-native plants in Australia would have come from Britain and it is interesting to note that 67% of the 54 plants introduced to Britain during the Roman occupation are now naturalised in Australia suggesting the amenability of a Mediterranean climate.

The love of roses so prevalent in Britain and evident over much of Australia’s gardening history can probably be attributed to the Romans who celebrated a festival of roses (Rosaria) each year in May and June.

By the end of the Roman era gardens have taken on many of the faces we might recognise today: a simple source of herbs, medicines, vegetables and fruits, a lovers retreat, a sanctuary, a decadent display of opulence, an idyllic paradise, a place of civilised and cultured learning.

Key points

- Distinction between agriculture which used ploughs in fields (agri) and horticulture which used the hoe and digging stick in a spaces referred to as gardens (horti)

- Gardening was introduced to Britain by the Romans

- Romans introduced the rabbit to Britain

Garden structures & practice:

- First systematic records of named plant cultivars

- Use of roses, lawns, topiary and trimmed box hedging

- Elaboration of the Greek peristyle garden

- Popular garden trees: plane trees and sycamore for public parks; cypresses, oak, pine and spruce; also mulberries, figs, bay (Laurus nobilis) and myrtle (Myrtus communis)

- Tools: the coulter, plough, sickle, billhook, 2-handed scythe, pruning hook, hoe, mattock, spud, rake, iron spade, iron fork, tuf cutter, ox goad, carding comb, axe

- Sculpture; hothouses; indoor and outdoor fountains; baths; fish pools; solariums; arbours; dovecots; outside dining areas; trellised pergolas; roof gardens; grottoes. Also song-birds and peacocks (a symbol of eternity)

- First to develop gardens as extensions to their houses[8]

- Female of the house maintains the garden and its food produce also flowers used on the household altar

- Physical labour was, by Greek gentleman, considered degrading a and this no doubt applied to the Roman aristocracy as well (except for warfare and athletics).[9]

- Garden a place of pleasure and relaxation (otium), a haven from busy city life (negotium)

- Avenues of plane trees

- Professional gardeners (topiarii) employed on the luxury estates of aristocrats and emperors as landscapers arranging plants often in symmetrical or designed patterns often with clipped evergreen hedges and trees

- Soil improvement with manure, chaff, straw, shells, seaweed and animal dung

- Market gardening used to provide vegetables, fruits, herbs and nuts for the garrisons and local markets

- Propagation by cuttings and seeds in clay pots

ROMAN REPUBLIC & EMPIRE

REPUBLIC BCE

Early Republic – 458-274

Middle Republic – 275-147

Late Republic – 148-27

EMPIRE CE

Western – 27 BCE – 476 CE

Eastern – 27 – 1453

ROMAN EMPERORS

1st CENTURY CE

Augustus - 31 BCE –14 CE

Tiberius - 14–37

Caligula - 37–41

Claudius - 41–54

Nero - 54–68

Galba - 68–69

Otho - Jan,-Apr. 69

Aulus Vitellius - July–Dec. 69

Vespasian - 69–79

Titus - 79–81

Domitian - 81–96

Nerva - 96–98

2nd CENTURY CE

Trajan - 98–117

Hadrian - 117–138

Antoninus Pius - 138–161

Marcus Aurelius - 161–180

Lucius Verus - 161–169

Commodus - 177–192

Publius Pertinax - Jan.-Mar. 193

Marcus Julianus - Mar.-Jun. 193

Septimius Severus - 193–211

3rd CENTURY CE

Caracalla - 198–217

Publius Sept. Geta - 209–211

Macrinus - 217–218

Elagabalus - 218–222

Severus Alexander - 222–235

Maximinus - 235–238

Gordian I (Mar.-Apr.) - 238

Gordian II (Mar.-Apr.) - 238

Pupienus Max. (Apr-July) - 238

Balbinus (Apr.-July) - 238

Gordian III - 238–244

Philip - 244–249

Decius - 249–251

Hostilian - 251

Gallus - 251–253

Aemilian - 253

Valerian - 253–260

Gallienus - 253–268

Claudius II Gothicus - 268–270

Quintillus - 270

Aurelian - 270–275

Tacitus - 275–276

Florian (Jun.-Sept.) 276

Probus - 276–282

Carus - 282–283

Numerian - 283–284

Carinus - 283–285

Diocletian (E Empire) 284–305

- divided empire into E and W

Maximian (W Empire) 286–305

4th CENTURY CE

Constantius I - W 305–306

Galerius - E 305–311

Severus - W 306–307

Maxentius - W 306–312

Constantine I - 306–337 (reunif.)

Galerius Val. Max. - 310–313

Licinius - 308–34

Constantine II - 307–340

Constantius II - 337–361

Constans I - 337–350

Gallus Caesar - 351–354

Julian - 361–363

Jovian - 363–364

Valentinian I - W 364–375

Valens - E 364–378

Gratian - W 367–383

- coemperor with Valentinian I

Valentinian II - 375–392

Theodosius I - E 379–392

E& W 392–395

Arcadius - E 383–395

- coemperor

395–402 sole emperor

Magnus Maximus - W 383–388

Honorius - W 393–395

- coemperor

395–423 sole emperor

5th CENTURY CE

Theodosius II - E 408–450

Constantius III - W 421 co-emp.

Valentinian III - W 425–455

Marcian - E 450–457

Petronius Max. - W Mr–My 455

Avitus - W 455–456

Majorian - W 457–461

Libius Severus - W 461–465

Anthemius - W 467–472

Olybrius - W Apr.-Nov. 472

Glycerius - W 473–474

Julius Nepos - W 474–475

Romulus August.- W 475–476

Leo I - E 457–474

Leo II - E 474

Zeno - E 474–491

Media Gallery

Ancient Roman Gardens

Emily Reburn – 2019 – Emily Reburn

Roman Food and Agriculture

Lane Gray – 2016 – 4:51

The Roman Domus

Houses of the Wealthy

Metatron – 2017 – 14:45

BBC Italian Gardens Rome Part 1of 4

Music Mountain & Moors – 2017 – 59:01

Wikipedia

Roman agriculture

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . 13 October 2022 – minor editing

. . . 27 July 2023 – minor editing

Roman Empire at the time of Trajan 117 CE–

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons