Late Middle Ages – 1100-1500

Medici Villa Petraia near Florence – c. 1500-1550

Laid out by Niccolò Tribolo a Mannerist artist employed by Cosimo I de Medici, the garden demonstrates the geometric formalism of the early Italian Renaissance

Geometric layouts were also used in the first modern botanic gardens that originating in Italy c. 1550

This was a fashionable private garden influencing the rest of Europe

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

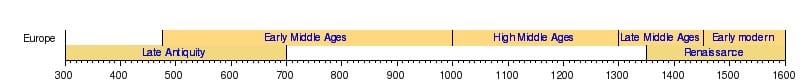

This article describes Medieval gardens in the historical period generally referred to as the High Middle Ages (c. 1000-1300) and Late Middle Ages (c. 1300-1500).[17]

This was a time of constant dynastic and territorial wars that included the loss of a newly acquired Scotland at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, the 100 years war over territories in France, and finally the War of the Roses which ended in 1485 with the defeat of the Plantagents at the Battle of Bosworth Field. The accession of Tudor Henry VII in 1485 has been used by historians as a convenient marker for the beginning of Renaissance England and the early modern period.

Devastation was at its greatest during the Great Famine and Great Plague exacerbated by the start of a Little Ice Age the rapidly growing population, problems in agriculture including the depletion of soil nutrients.

International context

The High Middle Ages are marked by a period of population increase and social change up to about 1250.

During the eleventh century large areas of forests and marshes across Europe were cleared, drained, and converted to cultivation.

The Catholic Church launched a series of Crusades against the Seljuk Turks.

Cultural change included a gathering ethnic awareness that would eventually lead into nationalism. There was a recovery of learning as the first universities appeared as developments from former religious schools while the study of Aristotle produced a mode of education and learning known as Scholasticism. There was a flourishing of Byzantine art and the building of magnificent Gothic cathedrals.

End of the Crusades

Islam had made major inroads into the former territories of Christendom, prompting four further Christian Crusades to regain lost lands. The Crusades of 1096 to 1487 engaged Christian and Muslim in an expensive 200-year religious contest for the Holy Land.

Second Crusade (1147-1149)

The Second Crusade was pronounced by Pope Eugene III in response to the fall of the County of Edessa (founded during the First Crusade) to the forces of Zengi. Edessa was the first Crusader state to be founded and the first to fall.

This Second Crusade was led by the European Kings Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe and, after crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both were defeated by Seljuk Turks. However, Louis and Conrad, with their depleted armies, reached Jerusalem and in 1148 made an unsuccessful assault on Damascus.

This Christian failure would influence the later fall of Jerusalem and initiate the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century.

Only one Christian success occurred when a combined force of 13,000 Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English, Scottish, and German crusaders on the way to the Holy Land aided a small contingent of 7000 Portuguese regain Lisbon from its Moorish occupants in 1147.

Third Crusade (1189-1192)

Saladin (1137-1193) was a Kurdish Suni leader who styled himself Sultan, as he expanded Muslim territory into Syria, Arabia and Egypt.

In 1187 he defeated a Christian army at the Battle of Hattin, taking the city of Jerusalem without bloodshed to become an Islamic hero.

The taking of Jerusalem prompted Pope Gregory VIII to declare another Christian Crusade with Saladin as the Devil. In 1189 Richard I (Richard the Lionheart) became king of England and dedicated more than half the nation’s revenue to the Pope’s cause, deciding to attack by sea in 1190 departing from Marseilles to land in Acre, Palestine where he soon met and defeated Saladin’s army, marching north to Jerusalem. However, with provisions held by his offshore fleet running low, and seemingly incapable of a protracted battle, he returned to Europe in 1192 without entering the city. At the same time Saladin, facing internal disaffection between his Turk and Kurd soldiers, decided to abandon Jerusalem.

Fourth Crusade (1202-1204)

The fourth Crusade (1202–04) gathered in Venice in 1203 with a fleet of over 200 ships intending to recapture Jerusalem from Muslim control with an invasion beginning in Egypt. However they were diverted to Constantinople by the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos to restore his deposed father as emperor before attacking the Holy Land with probably Byzantine financial and military assistance. In June, with the arrival of the fleet at Constantinople Angelos was crowned co-Emperor with crusader support but soon deposed as the residents rebelled. The murder of Alexios IV in early 1204 prompted the slaughter of residents, looting of icons, mosaics and buildings, and the establishment of a Latin empire partitioned between the conquerors.

However, the Byzantines fought back and Constantinople became Byzantine once again in a concluding phase of the Great Schism before Islamic rule.

The final fate of the Holy Land was decided in the 13th century in Egypt by the Mongols. The eastern extent of Christendom was marked by a narrow coastal strip of land extending from Antioch to Tripoli and Jerusalem, the remaining Crusader States. The continuing Crusades were fought by military orders of Knights, among them being the Hospitalers (initially caring for the poor but then adopting a military lifestyle), the Teutonic Knights and the better-known Knights Templar who maintained military forts in Acre and Palestine. Supported by the wealthy nobility they engaged un manufacture, minted their own money, and traded with their Islamic neighbours. The Crusading spirit was revitalised by the fervent French Louis IX who after recovering from a severe illness dedicated his life to restoring Christianity to the east, borrowed a vast sum of money and assembled a massive fleet of about 1800 ships and 25,000 professional soldiers. To achieve his objective he planned an attack on the Islamic power base in Cairo south of the mouth of Egypt’s Nile. Pressing south he was defeated and in 1250 he was captured, to be freed in humiliation for a vast ransom.

The Muslim army had employed the military skills of highly trained Russian steppe slaves called Mamluks who took over Cairo. However, to the north the Mongol armies of Ghengis Khan had created an empire that stretched from China to Europe and in 1260 threatened to take the Middle East. A Mamluk army met and defeated the Mongols in Galilee and tok Syria but the victorious Sultan was killed by a rival, Beibar, who returned to Cairo where he set up a Suni Caliphate as a highly organised military state. In May 1268 the Mamluks took Antioch in one day. Gradually the Crusader States were taken back and with the fall of Acre in 1291 the Middle Eastern Christian-Muslim conflict closed, the Christians simply onlookers through the final years.

Great plague

In 1348 the Great Plague struck as in 18 months half the population had died: the bubonic plague would eventually claim a third of the world population, while those that survived entered a new period of growth and prosperity.

As the new learning of the Renaissance gathered momentum the social and intellectual trends of Renaissance Italy passed across Europe to the cities emerging on Europe’s north-west Atlantic coast.

Age of Discovery

The Late Middle Ages was a period of major European globalization during the Age of Discovery and European colonial expansion as ships from the coastal cities of north west Europe sailed beyond the Mediterranean. In 1453 the Seljuk Turks captured Constantinople with many artists, intellectuals and merchants fleeing to the major cities of northern Italy that would become the epicentre of a Renaissance revival in ancient learning, art and trade..

The Age of Discovery began with the Portuguese and Spanish discoveries of the Atlantic archipelagos of the Canaries, Azores and Cape Verde (Madeira 1419; Azores 1427) then the coast of west Africa after 1434; rounding the Cape by Diaz in 1488; the establishment of a sea route to India’s Calicut by Vasco da Gama in 1498; the trans-Atlantic voyages of Christopher Columbus to the Americas between 1492–1502; Antonio de Abreu’s landing on the Spice Islands in 1512; and the first circumnavigation of the globe between 1519–1522 by the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan (completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano and Enrique of Malacca).

There followed a consolidation of trade routes across the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans, leading to land expeditions in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia that continued into the late 19th century. All this opened up global trade by European colonial empires, most notably the interaction between the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa) and the New World (the Americas and Australia), part of which was the Columbian exchange, a wide interchange of plants, animals, food, and human populations (including slaves). It also included communicable diseases (that decimated the already mistreated indigenous populations), religious, political and other cultural exchange between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres.

The mapping of the world’s continents set boundaries on the known world, encouraging biological inventory and further exploration and conquest.

British context

In England, with the arrival of the French Normans (of Viking ancestry) after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 came the Plantagenet dynasty bringing with it ideas, traditions, and conflicts from the continent and Eastern Mediterranean (see ‘Royalty’ below). The family originated in Anjou France, its 15 kings being the longest-serving dynasty, dominating England for nearly 300 battle-scarred years, conquering Wales and half of Ireland.

Landscape

The Black Death of 1348-9 was one factor in a period of economic decline that began in about 1300 during which land was abandoned, building programs ceased, farming was reduced and the total population of England had declined to probably about 3.5 to 4 million people. However, fortunes changed and, from about 1450 there was an economic resurgence in which farming shifted from arable to pastoral, the wool industry gained momentum, the construction of general housing and bridges, and especially churches, picked up up; canals were improved for the first time since the Roman occupation, and the population once again began to increase. Building standards reached a new high as a newly affluent class of rich tenant farmers, miners (especially the tin of Devon and Cornwall) and fishermen, became independent yeomen and merchants who could now afford, for the first time, substantial housing of their own.[12]

As regards the built environment Taylor in The Making of the English Landscape points out that the location of urban settlements was not always due to geography or the prevailing economics (resources and their availability, ports, mining and manufacturing centres) but also the result of selection by planners and administrators whether they be royal, parliamentary or religious. From the earliest days there is archaeological evidence indicating much rebuilding on former sites. After the 16th century, though expansion proceeded apace, few new towns were created.[13]

Around 1300 a Little Ice Age commenced that would last until about 1850.

Castles

Though a few castles were built in England in the 1050s, after the Norman invasion of 1066 William set about controlling his new territory by building motte and bailey castles with square keeps occupied by his barons, and increasingly constructed in stone. These Norman lords then had defended centres from which to manage their estates. These were also introduced to Scotland and Ireland in the 12th century.

London

By the 11th century London was by far the largest city in the country that in the 13th century had a population of around 80,000 people in two settlements: the exclusive and aristocratic royal precinct at the West End, dominated by the iconic Westminster Abbey (rebuilt by Henry III, beginning in 1245) and the eastern merchant City of London dominated by Guild Hall.

By the 12th century the strict hierarchy was beginning to dissolve. Rural life was becoming more peaceful, spreading out from the castles or the more recently built manor houses. Intra-dynastic territorial wars followed ending in 1216 with the death of King John marking a transition from the Angevin period (Anjou) to a Plantagenet dynasty. By this time the Church had become an independent organization answering to Catholic Rome which had inspired several Crusades against Muslim assertion in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Towns, especially along the eastern and southern coast were engaging in both local and continental trade.

The positivism that had developed up to 1250 was curtailed by the arrival of the Black Death in 1348 and the Little Ice Age, during a time of internal popular revolt and constant warfare between countries (The Hundred Years War) and the splitting of the Catholic Church into western and eastern chapters- known as the western schism.

In 1348 the Great Plague, Yersinia pestis, struck as in 18 months half the population died. Those that survived entered a new period of growth and prosperity.

The two settlements were divided by a river known as the Fleet which was filled in Tudor times the two combined settlement divided by Fleet Street as a major artery of communication between the two. In the 1530s about 60% of the property in London was owned by the Catholic Church and much of this property passed to Henry VIII in a land grab that including the 650 acre Hyde Park. Henry confiscated Whitehall and Wolsey’s Palace for himself, passing on other properties to his nobles.

Declining numbers of monasteries in the early 16th century showed increasing ornamentation and it was classical themes that took precedence in the new Renaissance mansions of the wealthy.

Famine & Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453)

Between 1300 and 1400 Britain experienced a famine in 1315, the start of the 100 years war (a battle for the French throne that lasted from 1337 to 1453) and the Great Plague (Black Death) in 1348. The Black Death decimated the peasantry, already weakened by Richard IIs Poll tax. Following the Black Death labour was once again in demand as wages rose and with peasant status increased it was possible to mount the Peasant’s Revolt against the Poll Tax in 1381. Peasants began copying the dress of their social superiors prompting the Act of Apparel which returned them to ‘their proper estate and degree’.

Royalty

Henry II (1154-1189) had inherited the throne at an early age and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Scotland to the Pyrenees, setting up a system of common law still used in the UK and US. By the time of Henry III most of the ancestral French lands had been lost and allegiances divided between the two countries. Henry III (1207– 1272) ruled from 1216 until his death as King of England, Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine. Most of the ancestral French lands were now lost and allegiances became divided between the two countries and he assumed the throne age 9 while there was a Baron’s rebellion, his knight-protector William Marshal defeating the rebels at the battles of Lincoln and Sandwich in 1217. Later he promised to abide by the Great Charter of 1225, which limited royal power and protected the rights of the major barons.

In 1230 the King attempted to reconquer the provinces of France that had once belonged to his father, but was repulsed. He married Eleanor of Provence who had five children. Henry was pious, rebuilding Westminster Abbey and spending prodigiously on castles much of the money obtained from English Jews. In a fresh attempt to reclaim lands in France, he invaded Poitou in 1242 but was defeated at the Battle of Taillebourg.

Henry’s rule became increasingly unpopular for his profligacy, tax collecting, and failed military campaigns. In 1258 fifteen barons seized power, reforming government through the Provisions of Oxford and sharing government through this ‘parliament’. Henry and the barons made peace with France in 1259, Henry abandoning his desire for French land in return for King Louis IX of France acknowledging him as legitimate ruler of Gascony. The baronial rule was disbanded but there was continued instability. Eventually in 1263 the baron Simon de Montfort, seized power prompting the Second Barons’ War. Henry called on Louis for support but was defeated at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 and taken prisoner. However, Henry’s eldest son, Edward, escaped and defeated de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham, liberating his father and succeeding him as king in 1272. Edward 1s rule would last until 1307 during which he captured Wales where he built impressive Medieval castles but was halted, in his attempt to take Scotland, by William Wallace at the Battle of Stirling Bridge and dying during a subsequent clash with Robert the Bruce. Edward II, who ruled from 1307 to 1327 had a quieter disposition, preferring to spend time in his garden and with his friend Piers Galveston resulting in conflict with his barons. Ground was also lost in Scotland where Edward’s army was decisively defeated by Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. The barons, managed to engineer Galveston’s death, Edward befriending Hugh Despenser as an advisor, but in 1321 Lancaster and some barons subsequently seized the Despensers’ lands Edward retaliating by capturing and executing Lancaster. Reaching a stalemate in the conflict with Scotland, Edward signed a truce with Robert the Great but Edwards popularity was low. His wife Isabella, when sent in 1325 to negotiate a treaty with France, turned against him and, with her exiled lover Roger Mortimer, she invaded England in 1326, Edward retreating to Wales but soon captured, relinquishing the crown to his fourteen-year-old son, Edward III (the Black Prince), in 1327.

Edward III ruled for 50 years restored respect for the monarchy by re-establishing his military power, the Kingdom of England undergoing important changes in legislation and government including the maturing of parliament, in spite of the huge toll wrought by the Black Death. When only aged 17 he defeated Mortimer, England’s ruler by default. Then winning ground in Scotland in 1337 he claimed the French throne (from the time of William the Conqueror, French had remained the language of the ruling class) from his cousin King Phillip but was resisted, a slur that launched the One Hundred Year’s War which began with English victories at Crécy and Poitiers forcing the Treaty of Brétigny. However, his later years were arred by international disgrace and civil strife in England itself.

Richard II (1377-1399) in squandering state money had clashed with his nobles notably Henry Boligbroke who, with the assistance of the nobles, deposed Richard. Perceived as a usurper and Lancastrian Henry IV launched 14 years of conflict. On on his death in 1413 was replaced by his son as King Henry V. Determined to regain power in France Henry V crossed the Channel in 1417 with 1500 ships, 8000 archers and 2000 men-at-arms on a rampage from city to city but gradually weakening he gained a surprising victory over the French army in 1415 at Agincourt. He had recaptured much of Normandy and having secured a marriage to Catherine of Valois was close to securing the French throne as well as most of France.

Royal bickering between two Plantagenet dynasties resulted in the Wars of the Roses (1455 and 1487), a conflict symbolised by the white rose of York and the red rose of Lancaster, ?ending with the triumphal enthronment of Lancastrian Henry IV (1366-1413) in 1399.

The people

Most people were peasants who lived as tenant farmers, free labourers or as villeins (serfs to a landlord: known as ‘houseboundmen’, hence the word ’husbandry’).

Peasants had cottages with an associated garden, this period ushering in the era of the English cottage garden.

Medieval villages had narrow lanes, stone churches, the manor, and peasant cottages with enclosed front gardens that grew vegetables, herbs and flowers that had been gathered from the field: primroses, cowslips, oxlip, mallow and the like and perhaps a few special plants that had been brought back by knights from the religious Crusades against the Muslims in the 11-13th centuries.[9]

Gardening and farming were closely associated. In the strip fields the peasants used home-made scythes, rakes and other tools and there was a special area of land, the garth, which was protected from wandering livestock and geese by ditches, palings and hedges of holly and hawthorn, which contained medlar, quince, plum, walnuts, chestnuts, filberts and vegetables of various kinds. These were all tossed into the daily pottage flavoured with strong herbs like nettles and docks along with onion and garlic. Wealthier peasants owned pigs, ducks, chickens cows and geese.[10]

Gardens

Through royal marriage connections the Plantagenets, the name possibly derived from Planta Genista, had associations with Burgundy, Provence, the Low Countries and Castile.

The record of castle gardens is poor. Troubadors and minstrels were not active until the 12th century and miniature painters until the 14th and 15th centuries. However, we know that The mistress of the castle (the châtelaine, or castle-keeper, from the Medieval Latin castellanus or castle occupant), following classical tradition, managed domestic affairs, the care of the sick, the kitchen, medicines and potions, and a patch of useful plants.

In 1110 Saxon King Henry I constructed a walled garden at Woodstock, Oxfordshire (Woodstock – a clearing in the woods) where, following classical tradition, he kept a menagerie that included lions and leopards, camels, lynxes and a porcupine, Henry II later replacing this with a maze called Rosamond’s Bower. Castles were simple with a motte and bailey (moat and drawbridge).[3]

Wives of Henry II (1154-1189) and Henry III (1216-1272) brought with them an entourage of servants that included gardeners who, following Roman, tradition set out herb gardens, chapel courtyards, orchards, vineyards, lawns and fountains.[1]

But gardens were also part of the lives of second-tier echelons of society, the private dwellings of merchants and courtiers. Outside London’s walls were manor houses owned by the wealthy each with its small estate of trees. Were these based on the hill garden retreats of Attic Greece?

Though gardens were hardly a feature of this period Edward III’s reign (1327-1377) was noted for its pageantry and encouragement of the arts while the Dominical Friar Henry Daniel (fl.1379) boasted about the 252 different plants in his garden at Stepney making him possibly England’s first botanical collector and gardening expert.[8]

Medieval gardens (400-1450)

Knowledge of Medieval gardens, even on a European scale, is poor as no gardens of the period exist, literature is sparse, and there are only a few illustrations dating mostly from after 1400. Much of what we know is derived from literature that mentions gardens only in an incidental way.[2]

Our interest in Medieval gardens relates to the general character of the horticultural tradition that arrived in Australia with its colonial settlers.

Following the departure of the Romans c.410 CE there is a true dark age with virtually nothing known until 800. With the Carolingian empire we hear not only of the plants in Europe but the existence of pleasure gardens and parks with animals and peacocks in relation to the monasteries and emperor probably reflecting the influence of eastern ‘paradise’ gardens.

Muslims of Persia and the Near East had translated into Arabic the classical learning of the ancient world the plant science being continued and taken by Abu Hanifah (c. 820-895) as the Book of Plants when the Muslims conquered Spain. Cordoba was to become a Western intellectual centre with the nearby palace city of Medina Azahara, constructed in about 936, displaying magnificent architecture, aqueducts, reception halls, mosques, baths and more. Vast terraced gardens and orchards were constructed with carefully nurtured plants specially imported from Africa, India, Syria and elsewhere and garden features that included singing birds, fragrant flowers and water wheels – but its glory was brief the city abandoned in 1010 after a civil war. Ideas like clover lawns as ‘flowery meads’, fragrant flowers, aviaries, water features, fruit trees were all appreciated by visitors from northern Europe. [3]

Apparently following the Roman tradition special areas were set aside in larger establishments for specific purposes. Kitchen gardens grew vegetables, fruit and herbs; physic gardens grew medicinal herbs either on a large scale and in discrete beds as in a large monastery, or as a few plants tended by the housewife for the home table.

Kitchen gardens and pleasure gardens

Pleasure gardens in larger houses were enclosed areas for relaxation with a lawn, paths, central water feature, flowery mead, border of roses, lilies, iris, peony and a few other bulbs, also trellises with vines, roses and ivy although illustrations indicate a variety of designs and evergreen plants were popular like box, juniper, and yew. Another kind of pleasure garden was based on tree plantings like fruit trees, quince, medlar, apple, pear, cherry and mulberry sometimes interspersed in woodland. Historian Harvey contests the existence of Medieval cloister gardens.[4]

Influence of eastern paradise gardens; existence of named apples, pears and other fruits; introduction of new plants from the East and Spain; specialised plant containers for transporting living plants, bulbs, and seed; plant transport for vast pleasure gardens in Spain; by the 13th century seed and plants were being sold, at least in major cities.

c. 900-1100

Hospital gardens were often run by women whose expertise lay in herbalism and the preparation of assorted ointments, poisons, infusions, purgatives, sedative, stimulants and other concoctions. It was still the classical work of Dioscorides’s (40-90 CE), De Materia medica, that served as the source of herbal authority.

Garden historian Jenny Uglow cites a list of garden plants recommended by the Augustinian abbot of Cirencester who taught at the universities of Paris and Oxford. Like the list of Charlemagne it speaks of the functional emphasis of these gardens – the prevalence of herbs (both culinary and medicinal) and vegetables. There were however a few functional plants that served as ‘adornment’ like roses, lilies, poppies, acanthus, peony, daffodil and pot marigolds:

The Abbot’s list included roses, lilies, turnsole, violets, mandrake, parsley, cost, fennel, southernwood, coriander, sage, savory, hyssop, mint, rue, dittany, smallage, pellitory, lettuce, cress and peonies. He recommended beds of onions, leeks, garlic, pumpkins, shallots, cucumber along with poppy, daffodil and acanthus. Pottage (herbs used for the regular diet of soup) herbs recommended were beets, herb mercury, orach, sorrel (Rumex spp.) and mallow.[5] There were areas for fruit (some tender and needing special care): pomegranate, date, lemon and orange.

Ancient tradition was clearly evident in basic features of kitchen garden, meadow, vegetable garden, pond, an area for domesticated animals. Courtyards, or cloisters as they were better known, tended to follow the Roman tradition with a rectilinear layout of paths, lawn and gravel and possibly a central water feature. They were intimate spaces used for peace, relaxation, meditation and sometimes romance. The original Persian-derived term ‘paradyse’ was used for the flower gardens at church entrance or special areas used to source flowers for the various church festivals.

c. 1100-1300 – Early Middle Ages

Different gardens: formal orchard; enclosed bower; little park of trees and walks and possibly animals, sometimes a walled garden with menagerie but most of this was the activity of the rich for the wealthy after the severity of the Norman castles. Royalty dictated fashion especially the Plantagenets (a royal dynasty continuing as the Houses of York and Lancaster and the War of the Roses) 1154-1399 (1485) brought ideas from Europe and the East. The Herb Garden was used by royalty and generally greater appreciation of gardens there being orchards and trees and gardens of all sizes in the cities as royalty in mid 12th century[6]. Then in 1260 Albertus Magnus a German Dominican cleric (1193/1206– 1280) defined the Pleasure Garden as it had probably developed over the previous 100 years as pleasing the senses of sight and smell with a lawn, fragrant flowers and herbs, turf benches and fruit trees or vine-draped pergola for shade and a central fountain.

The idea of the closely cropped and rolled lawn was now established in Britain and by 1279 lawn bowls had begun.[7]

“turf, stretch of grass,” 1540s, laune “glade, open space between woods,” from Middle English launde (c.1300), from Old French lande “heath, moor, barren land; clearing” (12c.), from Gaulish (cf. Breton lann “heath”), or from its Germanic cognate, source of English land (n.). The -d perhaps mistaken for an affix and dropped. Sense of “grassy ground kept mowed” first recorded 1733. In sport turf, pitch, field or green or Apparently from Laon, a town in France known for its linen manufacturing.

Plants

It is possible that during this period more plants were introduced than during the Roman occupation. Gardening historian Jenny Uglow paints a picture of the 12th century monasteries with a head gardener (hortulanus or gardinarius) and maybe vinyards, orchards and ponds stocked with edible fish. A range of vegetables would be grown for the regular diet of broth spiced with salt, mustard or vinegar and then there was also the weak ale produced from home-grown yarrow (Achillea) and tansy (Chrysanthemum) and probably a mead called Dandelion and Burdock brewed from fermented dandelion, Taraxacum officinale, and the roots of Burdock, Arctium lappa, not mention cider and other alcoholic beverages. Among plants grown in the kitchen gardens were beans, leeks, oats, hemp, rye and beehives for honey and wax candles. There waqs now a full set of gardening tools including axes, saws, spades, hoes, rakes, scythes, knives, buckets. Some tools were possibly the result of experiences on the Crusades among them being the wheelbarrow, a new introduction in the 12th century. Monks connected with their fellow orders on the continent, using Latin for communication, and exchanging plants and seed transported in special leather bags and airtight wooden containers.[8]

Plants were the medicines of the day and that would be what most gardens contained: Mallow, Marigold (Calendula officinalis), Valerian (Centranthus ruber), Comfrey (Symphytum officinaleTanacetum parthenium), and Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium).

Dianthus caryophyllus, Clove Pink, with rocks brought from Caen France and used to build Norman castles, Platanus orientalis and Anemone coronarius returned with the Knights Templar from the Holy Land during the Crusades, Pyrus ‘Warden’ from Burgundy monks to the Cistercians of Warden Bedford.

Ficus carica brought from Rome by pilgrim Thomas a Becket to the priory of West Tarring.[7]

Chivalry

From the 12th to 14th centuries in an era of knighthood, chivalry, and romantic love, the garden had become a special space for meals, storytelling, music, dancing, and all kinds of entertainment – even a pool for bathing.

A typical garden of the period consisted of a walled courtyard but there were formal orchards and small treed parks. The enclosed garden was Islamic in style in the tradition of Andalusia and Granada and brought to England from Spain, Sicily and southern Italy by the Normans.[2] In the era of courtly love enclosed gardens were the place for romance, for the lovers trysts of knights and their ladies.

Guilds

Gardening now entailed not only the diverse techniques of plant cultivation but also the specialist skills of grafting, pruning, overwintering and more. In the London of 1180 wholesale merchants formed a pepperers’ guild which later merged with the spicers’ guild. In 1345 the Worshipful Company of Gardeners was established as gardening expertise became formally recognized through a professional guild. Much later still, in 1429, the Grocers’ Company was formed. These guilds were the forerunners of apothecary associations – the term ‘apothecary’ combining the vocations of botanist, chemist, druggist, herbalist, merchant and physician and reinforcing the persistent vital role of herbs and spices in Western medicine.

‘In the 13th and 14th centuries the City had important royal, religious and lay residences and most of them had gardens, some of them quite large such as that of the Bishop of Ely with a perimeter of over 600 yards. These medieval gardens had fruit trees, vines, and herbs for the kitchen or for strewing on the floor. Vegetables were less important because this was an age of meat eating but lettuce, spinach, cucumber and cabbage were used for flavouring and sauces. Some gardens also had bee hives, because sugar was a rare commodity. Leisure use was important too and there were fine lawns with flowers such as violets, roses and lilies.’[15]

There are records of gardens in 1555 and in 1597 a collection of plants was advocated by the famed herbalist John Gerard.

Nurseries

Commercial nurseries (called ‘impyards’ after grafts which were known as ‘imps’) were scattered around the country and sold seed, plants, turf and trees used for orchards, hedging and fencing (especially willows, aspen, poplar and alder).[11]

John Harvey, the historical authority on this period of plant introduction and commerce, points out that monasteries and gardens of the nobility had, by 1100, taken on the business nurserymen and seedsmen and by the 13th century “. . . there was a commercial gardening trade, selling seeds and plants in large numbers at centres such as Paris, London, and Oxford.”[7]

Plant introduction

Crusading knights experienced the gardens of the Middle East with their Persian and Islamic influences bringing back with them the damask rose, carnation, jasmine, bulbs. Also trees and shrubs that included pomegranate, lemon, sour orange and Cedar of Lebanon.

Garden hedges included the native wild rose Rosa rubiginosa the Eglantine or Sweet Briar. The more ornamental Rosa ‘Alba’, the Great White Rose, emblem of Edward I the son of Eleanor of Provence, and the red Rosa gallica emblem of his brother Edmund. These roses would later symbolise the Houses of York and Lancaster in the ‘War of the Roses’.

More gardening traditions were imported from the Continent by Edward I with his famous castles at Carnarvon and Harlech. He married Eleanor of Castile who introduced Moorish elements from the East (and an Italian gardener). Plants including the Sweet Rocket, Hollyhocks (Rose of Spain), pears ‘Calville Blanc’ (then ‘Blandurel’) the orchards now rowed out with medlar, mulberry, quince, and cherry.

After 1399 wealth was increasing based on wool trade and manorial estates became more abundant complete with kitchen gardens, parks, enclosed herbers, fish ponds with herb plots.[4]

One glimpse into the plants grown in 14th century England is the list (incomplete) provided in John Gardyner’s The Feate of Gardening, although we do have a list of native trees, presumably cultivated, passed on to us by Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400). However, Harvey notes the difficulties of identification to species level as well as the possibility of mistakes of various kinds. Nevertheless, it gives some idea of the meagre cultivated flora of 1375-1400: about 33 trees including both forest trees and fruits, and 103 vegetables, salads, herbs and flowers.[14] This was truly a utilitarian flora of mostly medicinal plants and culinary herbs and stands in stark contrast to the several hundred thousand different kinds available in Britain today.[16]

Literature

In 1440 the first true gardening book was produced, Jon Gardyner’s The Feate of Gardening.

A popular encyclopaedia of the day was compiled by Bartholomew de Glanville. Completed in about 1224 it included a section on plants and gardens and referred to the ‘herber’ (virgultum), that part of the garden for pleasure as distinct from the kitchen garden. By 1260 the idea of the ‘Pleasure Garden’ for the times had emerged, its elements outlined by Dominican monk Albertus Magnus who borrowed from de Glanville in his De Vegetabilis et Plantis (c. 1260): a lawn, a bed of fragrant flowers and herbs, turf seats, fruit trees, a pergola covered with trailing plants and perhaps a central fountain. Another influential gardening manula of the period was Liber Ruralium Commodorum (c. 1304-1309) written by Pietro de Crescenzi.[6]

It was probably in this period of history when lawns were first taken seriously as turves were laid, trimmed and rolled as, by 1280, the game of lawn bowls had begun. The world’s oldest surviving bowling green is the Southampton Old Bowling Green which was first used in 1299.[5] There is the use of earthenware pots and wooden tubs.

Key points

-

Cottage garden, husbandry, Worshipful Company of Gardeners, Jon Gardyner’s The Feate of Gardening.

-

The first use of the word ‘lawn’ is derived from the French laund – a green space in the woods – and used in the 13th century to refer to the smooth green space of monastic cloisters which were themselves derived from the Roman peristyle gardens.

- Emergence of hereditary surnames in 13th and 14th centuries

Timeline of the Middle Ages

1066 - Norman invasion

c. 1300 to c. 1850 - The Little Ice Age lasts for about 550 years

1314 - England defeated by Scotland at the Battle of Bannockburn

1378-1417 - The Western Schism was a split within the Catholic Church when two men claiming to be the true pope ruled (by 1410 this was three) each excommunicating the another. The schism was ended by the Council of Constance (1414–1418).

1400-> -Italian Renaissance from the 15th (Quattrocento) and 16th (Cinquecento) centuries, spreading across Europe and marking the transition from the Middle Ages to Modernity

1419 -Portuguese discovery of Madeira

1427 - Portuguese discovery of the Azores

1434 --> - exploration of coast of west Africa

1440 - Advent of the Gutenberg printing press. Western European lists of medicinal plants appeared for the first time, not in copied manuscript form, but as printed herbals. From Spain and Portugal came the herbals of de Orta (1490-1570), Monardes (1493-1588), and Hernandez (1514-1580) and mention of plants from the New World and Asia. From Germany the works of Brunfels (1489-1534), Bock (1498-1554), and Fuchs (1501-1566), from the Low Countries Dodoens (1517-1585) appointed Professor of Medicine in Leiden in 1582, Lobel (1538-1616), and Clusius (1526-1609). From Italy Mattioli (1501-1577) who studied at the University of Padua in 1523 and Alpino (1553-1617) who assisted the establishment of the Botanic garden at this university in 1545. From England of this period came the herbals of Turner (c.1508-1568) and Gerard (1545–1612),

1453 - Seljuk Turks captured Constantinople with many artists, intellectuals and merchants fleeing to the major cities of northern Italy that would become the epicentre of a Renaissance revival in ancient learning, art and trade

1485 – The accession of Tudor Henry VII with the defeat of the Plantagenet Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field has been used by historians as a convenient marker for the commencement of both Renaissance England and the early modern period

1488 - Diaz rounds the Cape

1498 - Vasco da Gama finds sea route to India’s Calicut

1492–1502 - Christopher Columbus's trans-Atlantic voyages to the Americas

1512 - Antonio de Abreu lands on the Spice Islands

1519-1522 - Ferdinand Magellan's first circumnavigation of the globe between 1519–1522, completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano and Enrique of Malacca

CRUSADES

1096-1099 – Pope Urban II

1147-1149 – Pope Eugene III

1189-1192 – Pope Gregory VIII

1202-1204 – Pope Innocent III

BRITISH MONARCHS

SAXON - 802-1066

DANE (Viking) = D

Egbert - 802-839 - Wessex

Æthelwulf - 839-856

Æthelbald - 856-860

Æthelbert - 860-866

Æthelred I - 866-871

Alfred-the-Great - 871-899

Edward the Elder - 899-924

Athelstan - 924-939

Ælfweard - 924

Edmund I the Elder - 939-946

Eadred - 946-955

Eadwig the All Fair - 955-959

Edgar I - the Peaceful - 959-975

Edward the Martyr - 975-978

Æthelred II - Unready - 978-1013

Sweyn I Forkbeard - 1013-1014D

Æthelred II Unready - 1014-1016

Edmund Ironside - 1016

Canute the Great 1016-1035 - D

Harold Harefoot - 1035-1040 - D

Harthacanute - 1040-1042 - D

Edward t'e Confessor 1042-1066

Harold II - 1066

Edgar Ætheling - 1066

NORMAN - 1066-1154

William I - 1066-1087

William II - 1087-1100

Henry I – 1100-1135

Stephen of Blois – 1135-1154

PLANTAGENET - 1154-1485

Henry II – 1154-1189

Richard I Lionheart – 1189-1199

John Lackland – 1199-1216

Henry III – 1216-1272

Edw' I Longshanks – 1272-1307

Edw' II of Carnarvon - 1307-1327

Edward III – 1327-1377

Richard II – 1377-1399

Henry IV – 1399-1413

Henry V – 1413-1422

Henry VI – 1422-1461

Edward IV - 1461-1483

Edward V - 1483

Richard III - 1483-1485

TUDOR - 1485-1603

Henry VII – 1485-1505

Henry VIII – 1509-1547

Edward VI – 1547-1553

Lady Jane Grey/Dudley – 1553

Mary I/Mary Tudor – 1553-1558

Elizabeth I – 1558-1603

STUART - 1603-1714

James I – 1603-1625

Charles I - 1625-1649

Civil War – 1642-1651

Commonwealth - 1649-1653

Protectorate – 1653-1659

Charles II – 1660-1685

James II (VII Scotl'd) -1685-1688

Mary & William - 1688-1694

William of Orange – 1694-1702

Anne – 1702-1714

HANOVER - 1714-1901

George 1 – 1714-1727

George II – 1727-1760

George III – 1760-1820

George IV – 1820-1830

William IV – 1830-1837

Victoria – 1837-1901

SAXE-COB' GOTHA 1901-1910

Edward VII - 1901-1910

WINDSOR – 1910->

George V – 1910-1936

Edward VIII – 1936

George VI – 1936-1952

Elizabeth II – 1953->

EARLY UNIVERSITIES – FOUNDATION DATES

Bologna – 1088

Oxford – c. 1096

Salamanca – 1134

Paris – 1160

Cambridge – 1209

Padua – 1222

Naples – 1224

Siena – 1240

Montpelier – 1289

Lisbon – 1290

Coimbra – 1290

Madrid – 1293

Rome – 1303

Perugia – 1308

Florence – 1321

Pisa – 1343

Prague – 1348

Vienna – 1365

St Andrews – 1410

Glasgow – 1451

Aberdeen – 1495

CALIPHATES

Rashidun – 632-661

Umayyad – 661-750

Abbasid – 750-1258

Ottoman – 1517-1924

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Medical practitioners &

medical terms

Apothecary is the medieval name for a seller of drugs and spices loosely equivalent to today’s pharmacist as someone who prepares and sells medicines. When the medicines are plants or their extracts the person may be called a herbalist while a book that lists these plants, with their medicinal properties and probably some illustrations, is a herbal or, as in the case of Dioscorides work, a Materia Medica. The medicinal plants themselves may be known as botanicals, simples, or officinals and in ancient times their medicinal properties were referred to as virtues. Medicines supplied by apothecaries were generally mixtures of multiple or compound ingredients: ‘simple’ refers to one of these basic ingredients. ‘Officinal’ (of commerce) suggests that these simples were sold by the apothecaries. Sometimes the medicinal drugs (or the art of medicine itself) was called physic hence a garden of medicinal plants was known as a physic garden. In more recent times someone who studies drugs and their effects in a scientific way is known as a pharmacologist and the book, often a government publication, that lists the medicines, their formulas, preparation, strength and purity, is known as a pharmacopoeia and when plants are the specific source of drugs the study may be termed pharmacognosy. A physician is a medical practitioner who is highly skilled in diagnosis (rather than surgery), a specialist who has usually had a longer training than a doctor or GP.