Alfred Russel Wallace

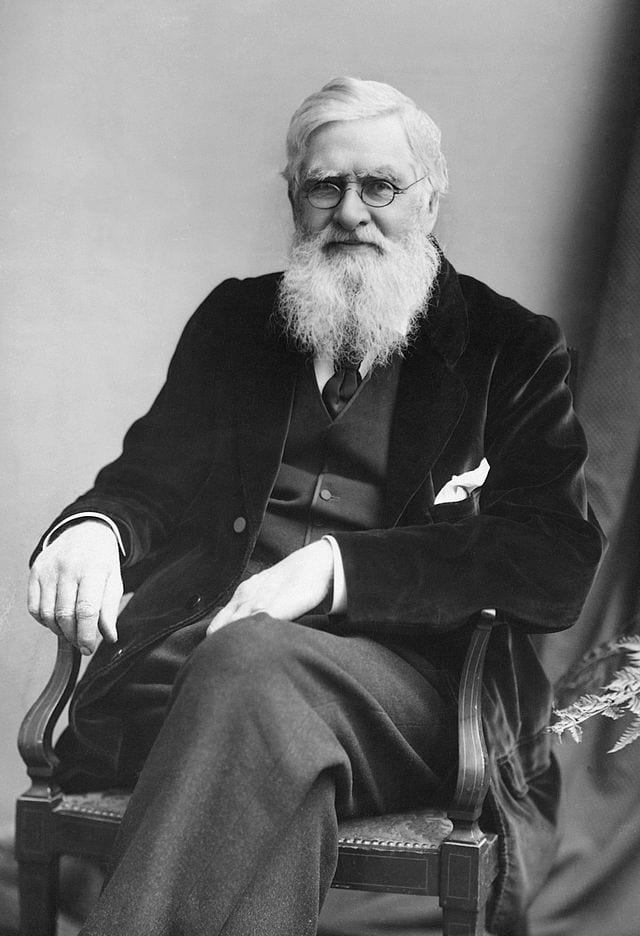

Alfred Russel Wallace c. 1895

First published in Borderland Magazine, April 1896, donated London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The introductory article Plant People sets the scene for the selection of plant people described in this series of articles, placing them within a global and plant science context. For a more extended discussion of changes in the form and context of plant study over time see the history of plant science.

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) was a brilliant and original scientific thinker, naturalist, traveller, and biogeographer. His background broke the prevailing mould of the gentleman naturalist of independent means. He was a modest man with strong ideas, from the emerging and newly educated and sometimes socially rebellious middle class, surviving for most of his life on meagre resources.

Wallace is best known for the Letter from Ternate, his independent discovery of the theory of natural selection, the letter nudging Darwin to finally publish his On the Origin of Species which had been gestating for decades.

Early life

Wallace was born in the small Welsh village of Llanbadoc, Monmouthshire as eighth of nine children in a Wallace family that claimed a relationship to William Wallace a leader in the thirteenth century Scottish Wars of Independence. Though educated in law his father fell on hard times and when Alfred was five the family moved to his mother’s English home in the county of Hertford, attending Hale Grammar School until he was 14 when declining family finances meant a return home, and before long he was forced to board in London with his brother John, an apprentice builder. Later in life he would regard himself as self-taught in natural history.

In London he quelled his natural curiosity reading books available in the London Mechanics Institute which acted as educational institutions for the working class but often associated with political disenchantment, in Alfred’s day this being the radical ideas of social reformers Robert Owen and Thomas Paine. Soon he became an apprentice travelling surveyor to his elder brother William for six years developing an interest in natural history when the pair moved to Neath in 1841. When the business crumbled Alfred took a position as schoolmaster teaching surveying at the Collegiate School in Leicester from 1844-1845 where, in his spare time he spent time reading in the Leicester library devouring the works of Malthus, Humboldt, Darwin, Lyell and Chambers and developing his other interests in natural history. Under the influence of entomologist Henry Bates began building up a collection of insects.

When William died in 1845 Alfred took over the business in Neath one commission being a design for the Neath Mechanics Institute where he was encouraged to give talks on engineering and natural history. Around this time he was reading books of scientific exploration like those by Von Humboldt and especially the 1848 account of a trip to the Amazon by American entomologist William Edwards seminal scientific books of the day that challenged the prevailing natural theology including the pioneering work of geologist Charles Lyell in his Principles of Geology (1830-1833) which extending geological history beyond the few thousand years suggested by Christian belief, Charles Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle (1839) with its fascinating story of natural history as biogeography, Robert Chambers’ evolutionary treatise Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844) which included ideas of stellar evolution and transmutation of species.

First expedition – Brazil 1848-1852

Inspired by his reading, in 1848 at the age of 25 Alfred set out with his entomologist friend Henry Bates aboard HMS Mischief for the Amazon rainforest in Brazil. Like others before the pair hoped to make collections that would raise money from museums and the acquisitive instincts of other avid collectors.

For four years Wallace remained in Brazil (1848-1852) working for a year on the coastal Belém do Pará but in 1850 after a disagreement the pair broke up, Bates following his own path and Wallace charting the Rio Negro and Uaupés Rivers until 1852 – taking extensive nots on many aspects of the natural history of the region. In 1849 he had been joined by his young brother Herbert came out along with and botanist Robert Spruce. In poor health Wallace returned to Britain in mid-1852 leaving this pair behind to work for a further decade his brig HMS Helen which about one month into the return trip caught fire, to be abandoned by the crew along with two years of Wallace’s collections, very little being saved, the survivors drifting in two open boats for 10 days before being picked up and returned to London. Insurance paid out on specimens along with the sale of some of his surviving collections gave him over a year to establish contact with kindred naturalists, including Charles Darwin, and to begin publishing scientific papers and two books: Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses (1853) and Narrative of Travels on the Amazon (1853).

Second expedition – Malayan Archipelago 1854-1862

Keen to extend his biogeographic experience Wallace now headed for the East Indies in Malaysia across to Indonesia, still hoping to fund his studies through sale of specimens.

‘ . . . With a young assistant, Charles Allen Wallace would spend nearly eight years in the region, undertaking sixty or seventy separate journeys resulting in a combined total of around 14,000 miles of travel. He visited every important island in the archipelago at least once, and several on multiple occasions, and collected almost 110,000 insects, 7500 shells, 8050 bird skins, and 410 mammal and reptile specimens, including probably more than 5000 species new to science. His best known zoological discoveries are Wallace’s Golden Birdwing Butterfly (Ornithoptera croesus) and Wallace’s Standard-Wing Bird of Paradise (Semioptera wallacei), both from Bacan island, and Rajah Brooke’s Birdwing Butterfly (Trogonoptera brookiana) from Borneo. The book he later wrote describing his work and experiences there, The Malay Archipelago, is the most celebrated of all travel writings on this region, and ranks with a few other works as one of the best scientific travel books of the nineteenth century.[2]

Beetles were his great passion but it was during this period that his cogitations on natural selection were taking shape, expressed in the epoch-shattering letter to Darwin in 1858. His record of this period was eventually published as The Malay Archipelago (1869) and an instant best-seller, which it remains today.

While staying in a small house in Sarawak, Borneo, Wallace sketched his famous ‘Sarawak Law’ paper On the Law Which Has regulated the Introduction of New Species, which summarised his views on geology and its relation to biogeography as well as his cogitations on organic evolution. His final paragraph read:

It has now been shown, though most briefly and imperfectly, how the law that “Every species has come into existence coincident both in time and space with a pre-existing closely allied species,” connects together and renders intelligible a vast number of independent and hitherto unexplained facts. The natural system of arrangement of organic beings, their geographical distribution, their geological sequence, the phænomena of representative and substituted groups in all their modifications, and the most singular peculiarities of anatomical structure, are all explained and illustrated by it, in perfect accordance with the vast mass of facts which the researches of modern naturalists have brought together, and, it is believed, not materially opposed to any of them. It also claims a superiority over previous hypotheses, on the ground that it not merely explains, but necessitates what exists. Granted the law, and many of the most important facts in Nature could not have been otherwise, but are almost as necessary deductions from it, as are the elliptic orbits of the planets from the law of gravitation. Sarawak, Borneo, Feb. 1855.

Reading this paper Charles Lyell was prompted to visit (Darwin) at Down House in April 1856 and hearing his theory of natural selection recommended that Darwin immediately publish his ideas. Darwin was indeed forced into action but he eventually decided on a book rather than a paper.

The precise mechanism of evolution still evaded Wallace until in February 1858 during an attack of fever in the village of Dodinga on the remote Indonesian island of Halmahera his ideas crystallised sufficiently for him to send a draft of his theory to Darwin via the island of Ternate. His essay titled On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type was read to the Linnean Society at the same meeting as Darwin’s exposition on natural selection thus giving the pair equal credit.

Return home – 1862-1876

Wallace returning to England in 1862 with little money, lodging with his sister Fanny and her husband Thomas. However, his scientific reputation was now established he could deliver lectures and enjoyed the company of luminaries and his former heroes Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin, as well as the popular writer on evolution Herbert Spencer.

While away, Wallace’s specimens had been sold by his agent and the income wisely invested but Wallace had retuned to make poor financial decisions so he was forced to fall back on his publications since he could not find a suitable job. He was supported to a degree by both Darwin and Lyell as he wrote and edited scientific papers, Darwin especially lobbying for an eventual 200 pound annual government pension which was finally awarded in 1881.

His correspondence with Darwin increased on a variety of topics including sexual selection, warning colouration, and the possible effect of natural selection on hybridisation and the divergence of species.[30][31]

After an unsuccessful engagement lasting a year Wallace developed a new relationship, this time with Annie Mitten who he had met through botanist friend Richard Spruce who was himself a friend to Mitten’s father who studied mosses. The couple were married in 1866 and with his old surveying knowledge Wallace built a property, The Dell, where he and Annie produced three children but they left London in 1871, living in several different places in the south of England before settling at Broadstone, Dorset which is where he died.

Wallaces highly popular account of his time in South-East Asia was published in 1869 as The Malay Archipelago and this was followed in 1876 by his Geographical Distribution of Animals which outlined his views on the subject that interested him most, zoogeography.

Wallace’s keen mind was not confined to his interests as a naturalist. He had for a while, starting in 1865, become enthralled by spiritualism later becoming more politically active.

Science 1880-1890s

Now a scientific notoriety Wallace set out in 1886 on a ten month’s lecture tour in America where his brother John had taken up residence in California. His popularity had risen after publication in 1880 of his Island Life, a follow-up to The Geographic Distribution of Animals (1876). Though evolution was the main topic he also found time to discuss biogeography and political reform, not to mention his special interest in spirituality.

Visiting Colorado he teamed up with botanist Alice Eastwood botanising in the Rocky Mountains. This was to give him the material for an 1891 paper English and American Flowers linking glaciation to similarities in the floras of North America, Europe and Asia. He was quite happy with the naming of evolutionary theory ‘Darwinism’, even making this the title of a book published in 1889 which summarized the material he had delivered in his American lectures.

His collections

Most of Wallace’s prolific collections were sold to collectors and dispersed across the world. However, it is believed that he did keep a set of educational specimens for himself in a rosewood cabinet comprising a wide range of insects, shells, pods and items in interest to natural historians.

This rosewood cabinet was purchased for $600 in 1979 by Robert Heggestad in Washington DC in Washington DC. He eventually found out who had assembled the collection publishing a 62-page summary of the contents and evidence of its provenance.

Political activism from 1870

The political battles and debates he experienced as a young man had surfaced in remarks written in The Malay Archipelago these catching the eye of reformer, philosopher and utilitarian John Stuart Mill (1806-1873). This was a prelude to a period of political activism which, between 1873 and 1879, was strongly oriented towards Land Tenure Reform and his concern over land abuse by the gentry.

Land tenure reform

Wallace maintained that land should be owned by the state and leased out to the general benefit of the community. This and his later social concerns would earn him a reputation as a political radical.

‘In 1881, Wallace was elected as the first president of the newly formed Land Nationalisation Society . . . In the next year, he published a book, Land Nationalisation; Its Necessity and Its Aims, on the subject. He criticised the UK’s free trade policies for the negative impact they had on working-class people . . . After reading progress and Poverty, a best-selling book by the progressive land reformist Henry George, Wallace described it as ‘Undoubtedly the most remarkable and important book of the present century’.[1]

Resistance to eugenics

For Wallace as for Darwin evolution had raised the issues of social evolution, ethnic and racial differences, and the question of whether evolution had favoured certain people in the past or was active in the present or should be given a helping hand to move the ‘right’ people in the ‘right’ direction.

Like other eminent thinkers Wallace opposed eugenics because he did not think it was possible decide who was fit or unfit and therefore to be subjected to human-imposed natural selection. He addressed the issue in an 1890 article Human Selection where he pointed out that the successful in society – namely the wealthy – were not necessarily either the most intelligent or virtuous.

Other views

In many ways Wallace’s political passions and general beliefs were ahead of his day, his intellect ranging over many topics and gaining him a reputation as an eccentric. In 1898 he advocated abandoning the backing of money with hoards of gold and silver, preferring unbacked paper money. While a staunch advocate of womens’ suffrage he resisted the use of vaccination.

‘In 1898, Wallace published a book entitled The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and Its Failures about developments in the 19th century. The first part of the book covered the major scientific and technical advances of the century; the second part covered what Wallace considered to be its social failures including: the destruction and waste of wars and arms races, the rise of the urban poor and the dangerous conditions in which they lived and worked, a harsh criminal justice system that failed to reform criminals, abuses in a mental health system based on privately owned sanatoriums, the environmental damage caused by capitalism, and the evils of European colonialism. Wallace continued his social activism for the rest of his life, publishing the book The Revolt of Democracy just weeks before his death’.[1]

His interest in Spiritualism continued through his life as he tried to reconcile his scientific and religious beliefs, regarding the human intellect a consequence of a ‘Higher Intelligence’, raising scientific eyebrows by claiming the non-material origin of the higher mental faculties.

1823: Born in Wales, UK.

1848: Embarked on Amazon expedition.

1858: Developed theory of evolution by natural selection (jointly with Darwin).

1862: Published “The Malay Archipelago.”

1876: Presented on spiritualism.

1881: Elected as the president of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

1883: Became a member of the Royal Society.

1913: Passed away in Dorset, UK.

Commentary

In his twilight years Wallace reflected on his past in My Life (1905) and in The World of Life (1910) he summed up his scientific thinking.

Wallace was eventually a much-decorated man, his awards including the coveted Royal Society Copley Medal for outstanding scientific achievement and an Order of Merit from the monarch: he had become a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1872 and the Royal society in 1893. Appropriately a genus of plants from the Amazon was named Wallacea by the botanist Richard Spruce, a kindred spirit who had worked for 15 years in the Brazilian Amazon jungle. Like Darwin he displayed a self-effacing modesty under which lay ideas that would deeply challenge his society. Unlike Darwin he was of lowly social origin, without financial means and unable to secure a salaried position only obtaining a government pension through Darwin’s initiative in 1881.

Evolutionary biogeography

Wallace was virtual founder of the field of evolutionary biogeography and perhaps the most outstanding tropical field biologist of the nineteenth century time spent in the field singled him out as an extraordinary naturalist of his day. But only in recent times has his name been revived and linked firmly with that of Darwin in the history of evolutionary ideas. His political views and willingness to take an outspoken and controversial position on intellectual and social issues combined with his lowly origins probably counted against him. As an intellectual his interests spanned not only the cutting edge of his own scientific discipline but the controversies and concerns of the society of his day.

Environmental ethics & conservation

Wallace, like other biologists including Ferdinand Mueller, was sensitive to deforestation and its effects on climate and the way that massive erosion that followed clearance and heavy rainfall especially in the tropics, all discussed in his Tropical Nature and Other Essays (1878) to these concerns he added the threat of invasive organisms that he had witnessed after the European colonisation especially the devastation that occurred so often on islands, that of Saint Helena being especially notable as a consequence of erosion following the destruction of vegetation by the rapidly-breeding Portuguese-introduced goats that had been introduced in 1513. Later in The World of Life (1911, p. 279) he joined the small group of environmental ethicists that were 50 years ahead of public concern.

These considerations should lead us to look upon all the works of nature, animate or inanimate, as invested with a certain sanctity, to be used by us but not abused, and never to be recklessly destroyed or defaced. To pollute a spring or a river, to exterminate a bird or beast, should be treated as moral offences and as social crimes; … Yet during the past century, which has seen those great advances in the knowledge of Nature of which we are so proud, there has been no corresponding development of a love or reverence for her works; so that never before has there been such widespread ravage of the earth’s surface by destruction of native vegetation and with it of much animal life, and such wholesale defacement of the earth by mineral workings and by pouring into our streams and rivers the refuse of manufactories and of cities; and this has been done by all the greatest nations claiming the first place for civilisation and religion![1]

Wallace was a vegetarian, liked to attend séances, believed women should have the right to vote and advocated ideas that today would be considered those of an environmentalist.

In a 2010 book, the environmentalist Tim Flannery claimed that Wallace was ‘the first modern scientist to comprehend how essential cooperation is to our survival,’[155] and suggested that Wallace’s understanding of natural selection and his later work on the atmosphere can be seen as a forerunner to modern ecological thinking.

Media Gallery

Alfred Russel Wallace – the forgotten father of evolution

Biographics – 2020 – 22:07

Alfred Russel Wallace, Father of Intelligent Evolution?

Discovery Science – 2021 – 1:01:01

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

… 23 April 2021 – substantial revision

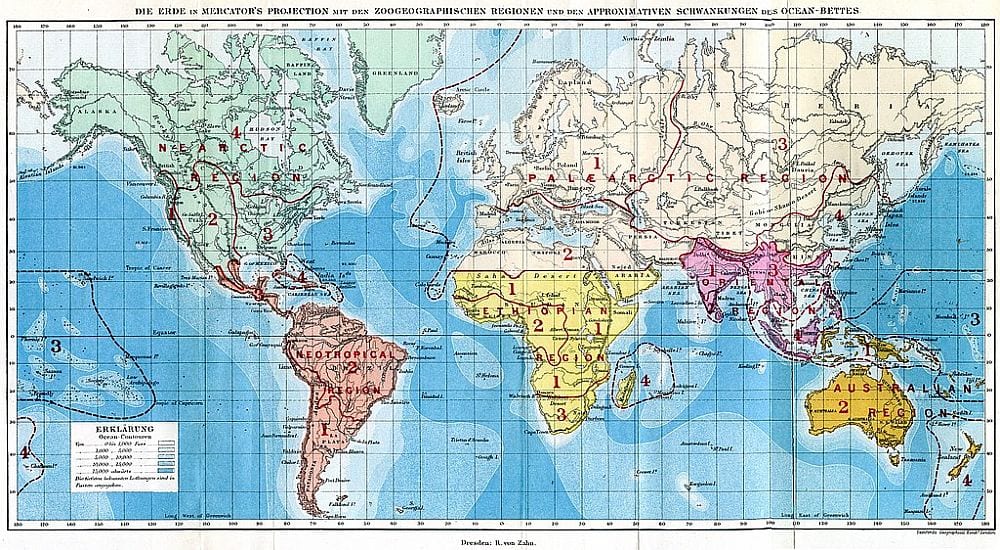

English: World map showing the zoogeographical regions – A map of the world from The Geographical Distribution of Animals shows Wallace’s six biogeographical regions.

Meaning of numbers:

Palæarctic region:

1. Central and Northern Europe

2. Mediterranean sub-region

3. Siberian sub-region (Northern Asia)

4. Japan and North China (Manchurian sub-region)

Nearctic region:

1. Californian sub-region

2. Rocky Mountain sub-region

3. Alleghany sub-region

4. Canadian sub-region

Ethiopian region

1. East African sub-region (Central and East Africa)

2. West African sub-region

3. South African sub-region

4. Malagasy sub-region (Madagascar and Mascarene Islands)

Oriental region

1. Indian sub-region (Hindostan)

2. Sub-region of Ceylon and South India

3. Indo-Chinese sub-region (Himalayan sub-region)

4. Malayan sub-region (Indo-Malaya)

Australian region

1. Austro-Malayan sub-region

2. Australian sub-region (Australia and Tasmania)

3. Polynesian sub-region (Pacific Islands)

4. New Zealand sub-region

Neotropical region

1. Chilian sub-region

2. Brazilian sub-region

3. Mexican sub-region

4. Antillean sub-region

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Dysmachus – Accessed 23 April 2021

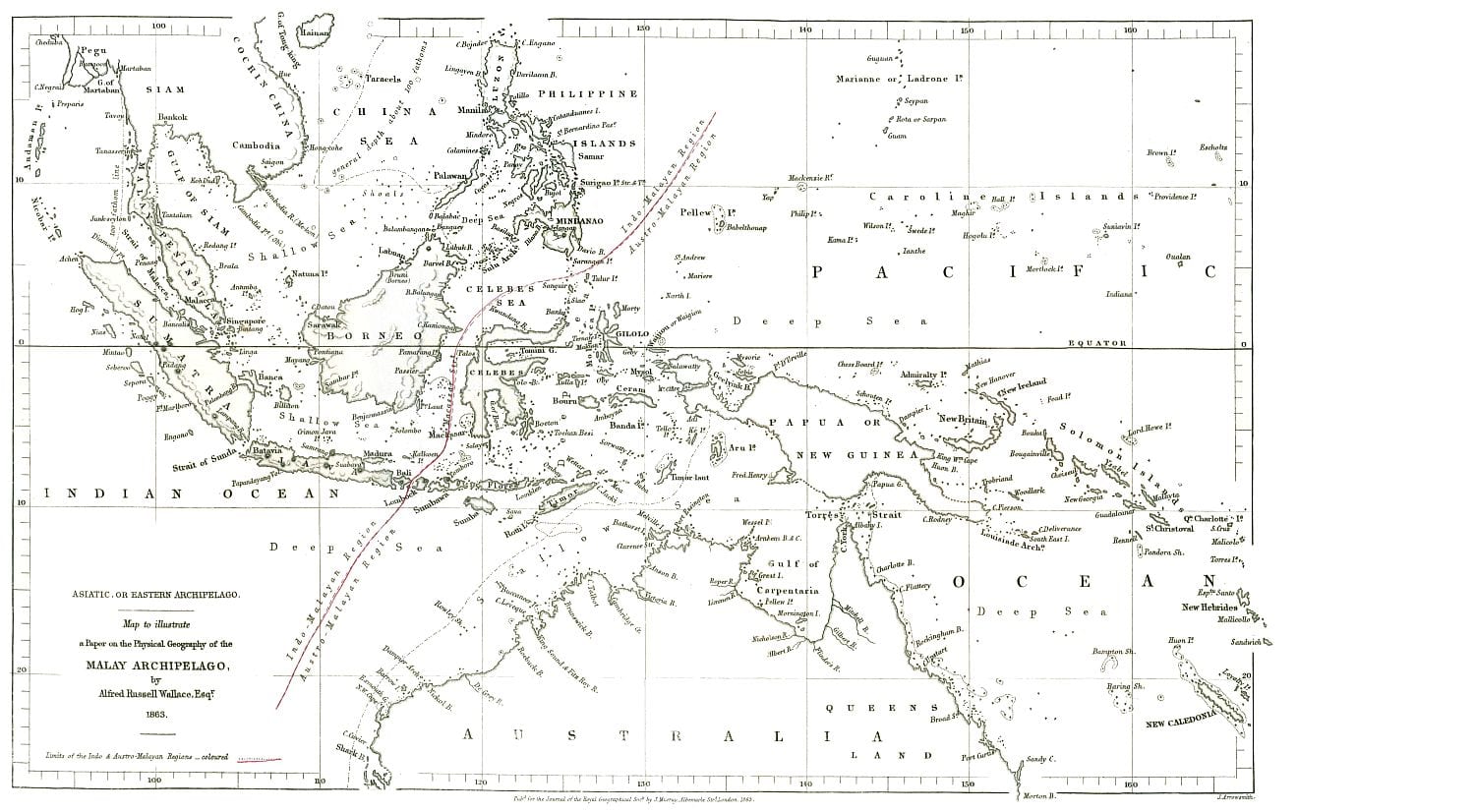

Wallace’s Line – The line separating the Indo-Malayan and the Austro-Malayan region in Wallace’s On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago (1863)

The term ‘Wallace Line’ was coined by Thomas Huxley in 1868 to commemorate Alfred Wallace who in 1859 noted a boundary between the distinct biological communities of Asia to the north-west and those of Asia and Australasia to the south-east. Islands near the boundary have been grouped together as Wallacea, with their own distinctive species.

The Wallace line extends from the Indian Ocean through the Lombok Strait between the islands of Bali and Lombok north through the Makassar Strait between Borneo and Sulawesi (Celebes) and eastward south of Mindanao to the Philippine Sea. The demarcation is more marked for animals than plants being a limit of distribution for many mammals, birds and fish.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Shyamal – Accessed 23 April 2021