Ancient Egyptian gardens

Garden of Sennufer who lived in the reign of Amenhotep II (c. 1427 to 1401 BCE) A 19th century copy of an original Egyptian painting found in the funerary chapel of Sennufer

This walled garden was probably near the Temple of Karnak in Easten Thebes. Visitors arrived by boat, passing (on the right of the plan) through a lodge to a central vine-shaded courtyard with trellised arbors and awned pavilions. Garden pools are decorated with flowering plants, occupied by ducks and decorated with poolside potted lotus. Similar original illustrations indicate that pools were stocked with edible fish. This was a place where wealthy households could relax in walled villa estates, often situated outside the city limits as a retreat from the trials of daily life. Shady colonnaded watered courtyards were the source of clean water Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The series of articles on historical gardens focuses on garden structures and practices that have become part of cumulative horticultural tradition.

If we define gardens loosely as places where plants are grown for their beauty and rarity as well as their utility, then among the first recorded gardens to emerge in the written record of the West are those in of Egypt and Mesopotamia, ancient civilizations that were sustained by water from the deltas of the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates rivers. The annual food cycle depended on the inundation by the fertile flooding waters of the Nile that occurred in late summer, followed by planting and cultivation in winter, with harvesting at the end of winter and in early summer.

The gardens of Egypt and Mesopotamia exhibit many of the characteristics we associate with gardens of today as they had an obvious influence on the civilizations of Greece and Rome that would dominate later western culture. This was a tradition whose apogee was the great Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, along with the Egyptian and Assyrian palaces with their monumental architecture, massive doorway statues, and sumptuous palace decoration in bronze, gold and silver.

Archaeology has unveiled a suite of plants cultivated for their beauty, utility, or symbolism exchanged through a trading network of cultures that included ancient Egypt, Minoans in Crete, Assyrians in Mesopotamia, and Myceneans of mainland Greece.

We know about the plants and gardens of ancient Egypt (2600-350 BCE) from funeral bouquets and wreaths found in tombs, also the paintings and reliefs found in ancient tombs and the references to gardens, trees and flowers that occur in hieroglyphic texts engraved on stone, as motifs on jewellery, pottery and other household objects, or written on scrolls called papyri that were made from the pith of the rush Cyperus papyrus. We have, for example, accounts written by senior officials of the Old Kingdom describing how they returned from town to enjoy the pools and groves of trees on their estates.[3] These gardens demonstrate many of the elements of the modern Western garden although they were mostly utilitarian plants that included Sycamore Figs (Ficus sycamorus), Common Fig (Ficus carica), Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera) Pomegranate (Punica granatum), grapes (Vitis vinifera), Papyrus reed (Cyperus papyrus), Sacred Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), they were clearly carefully arranged to please the eye and display the beauty of the plants to best effect: they were landscaped.

Historical context

Upper and Lower Egypt were unified under the first Pharoah in about 3150 BCE, subsequent history divided into three stable Kingdoms: the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BCE) of the Early Bronze Age, the Middle Kingdom (2134-1690 BCE) of the Middle Bronze Age, and the New Kingdom (1549–1069 BC) of the Late Bronze Age, each separated by an unstable Intermediary period. Egypt was at its zenith during the New Kingdom, when it rivalled the Hittite, Assyrian, and Mitanni Empires. From more utilitarian gardens of the Egyptian Old Kingdom over 4,000 years ago evolved the elaborate pleasure gardens of the New Kingdom that already expressed some formal characteristics that we would recognize in our parks and gardens today.Old Kingdom – 2350-2150 BCE

Perhaps the oldest known written description of a ‘garden’ is an Old Kingdom grove of trees planted adjacent to the pyramid of King Sneferu (reigned c. 2613-2589 BCE), first king of the 4th Dynasty at Dahshur and dating to about this period.[8] We find this record writen on the tomb wall of Methen or Amten, Governor of the northern delta district. Occupying about 1 ha his garden boasted a vinyard, large lake, and fine trees almost certainly planted in a formal style as depicted in later tomb paintings.[22] Reliefs depicting men working in orchards and vegetable plots date to the Sixth Dynasty at Saqqara (2345-2181 BCE), and tomb paintings from el-Bersheh and Ben hasan dating to c. 1800 BCE show square vegetable patches with raised edges tended by men gathering lettuces and onions.[10] During the Old Kingdom of 2350-2150 BCE the estates of wealthy men were used for farming, the houses having formal geometrically arranged beds, pools and trees, but they were utilitarian with fruit trees and vegetable plots. Though gardens were clearly ‘landscaped’, no illustration of an ornamental garden exists from the period of the Old Kingdom.Middle Kingdom – 2134-1690 BCE

Mentuhotep II, who reigned c. 2046 – 1995 BCE, was a Pharaoh of the 11th dynasty who ended the First Intermediary Period by reuniting Egypt to become the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom. The tomb of his Chancellor, Meketre, contained what is possibly the first formal representation of a garden layout as a doll’s house sized wooden model with pool, sycamore trees, and pillars sculpted as papyrus.[23] The Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1802 BCE) was a 200-year Golden Age of stability marked by industrial and intellectual activity beginning with the great military and administrative leader Amenemhet I, . Ineni, a builder for Tuthmosis I (reigned 1528-1510 BCE), listed his orchard trees taken to be Phoenix dactylifera, Ficus sycomorus, Mimusops laurifolia, Zizyphis spina-christi, Punica grantum, Myrtus communis, Medemia argun, Salix subserrata, Tamarix spp. and Twn tree (possibly Acacia nilotica).[25]New Kingdom – 1500-1250 BCE

In the period of the New Kingdom from 1500-1250 BCE the Nile floodplain allowed year-round irrigation for vegetables, palms, fruit trees. Design elements have become more complex with enclosed estates, elaborate architecture, groves of trees, pavilions, temples, and pools for lotus and birds. From about 1500 BCE ‘native trees and flowers were being steadily augmented by foreign introductions from the east and south-east of the Mediterranean‘ including the pomegranate, Punica granatum, from the Caspian Sea region, also Cornflower, Centaurea depressa, and Poppy, Papaver rhoes, from the eastern Mediterranean.[23]

By 1350 BCE in El Amarna there are grand houses with enclosed gardens laid out in suburban style, some relatively informal. There are wall frescoes of plants and landscapes in open areas fronting pools and courtyards. Gardens as sanctuaries now feature in art, literature and poetry, often with strong symbolic associations.[2] Thebes in about 1,400 BCE was a ceremonial capital with an elaborate landscaped urban space of temples and trees set on the Banks of the Nile.[4] There is also the first painting of the shaduf a water lifting fulcrum used for horticulture and still popular in India and Egypt.[4] Gardens were clearly associated with the symbolism of an afterlife and plants were sometimes associated with deities, like the connection of the Dom Palm, Hyphene thebaica with the god Thoth.[4]

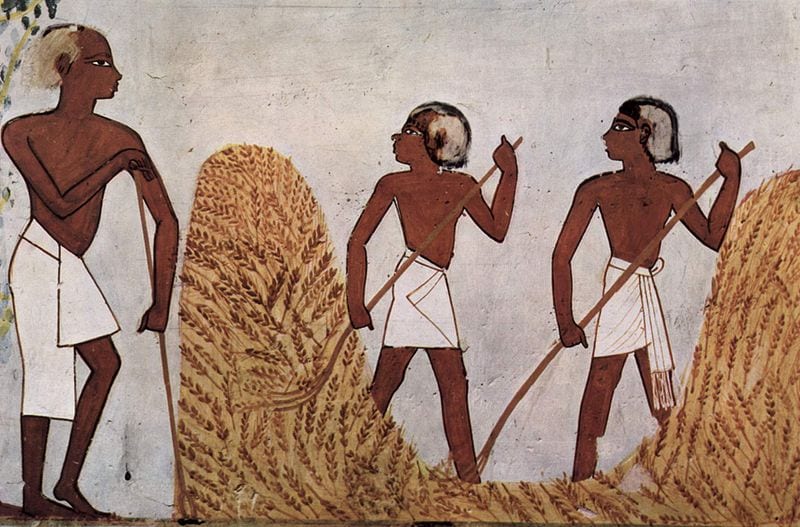

Wheat farmers at work

Painting in the tomb of Menna an ancient Agyptian artisan and ‘Scribe of the Fields of the Lord of the Two Lands’, probably in the reign of Thutmosis IV c. 1422-1411 BCE

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Trading expeditions to Punt (a trading partner that produced gold, aromatic resins, African blackwood, ebony, ivory, slaves and wild animals) located either in the region of Ethopia and Somalia or maybe the Arabian Peninsula, are recorded from the Fifth Dynasty c. 2400 BCE but others had followed in the sixth, eleventh, and twelfth dynasties, the latter commemorated in popular Egyptian literature through the Middle Kingdom’s Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor which must count as one of the first of a genre best exemplified in Homer’s Odyssey. An inexperienced heroic sailor becomes lost at sea following a storm after which he discovers a magical island and prevails over monsters of the deep and other trials and tribulations before returning home.

Tree transportation by boat

Relief showing a tree in transit from Punt to Egypt

Deir el Bahari Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, pharaoh of the 18th dynasty of Ancient Egypt, reigning from c. 1479 to 1458 BCE

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Queen Hatshepsut (1508–1458 BCE) was the fifth and much-revered pharaoh of the Eighteenth dynasty (‘for whom all Egypt was made to labour with bowed head‘)[24] was an accomplished leader who after restoring broken trade networks sent another expedition to Punt. It consisted of five ships, each about 21 m long with several sails and a complement of over 200 men including 30 rowers. The expedition returned with 31 live myrrh trees[9] stored with their roots in baskets and returned with some people from Punt itself. This appears to be the first recorded transplantation of trees from a foreign expedition. Hatshepsut planted the trees in the courtyard of the Deir el Bahri tomb complex which she dedicated to the god Amon. Soon after the Punt expedition Hatshepsut sent raiding parties to Byblos and Sinai and early in her reign had initiated successful military campaigns to Nubia, the Levant and Syria. We also know from tomb paintings that Egypt was in contact with the Aegean (Crete and Thera) during this period.[14]

The account of Hatshepsuts’s exploits must surely be among the first outlining the familiar theme of military conquest, the spoils of trade and war accompanied the heroism of long sea voyages with the challenges and spectacles that they provide providing a model for Alexander the Great and the Lyceum garden of Aristotle and Theophrastus and 1800 years later the European Age of Discovery, and later voyages of scientific discovery: heroic Banks and Solander, plant collectors facing the trials and tribulations of global circumnavigation and the delights of the enchanted islands of Otahiti. Enlightenment ‘Shipwrecked Sailors’ repeating the pattern of exploits carried out over 3000 years before.[see Wikipedia Hatshepsut and Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor]

Hatsheput’s successor was Tuthmosis III (1479-1425 BCE) who in his reign of nearly 54 years waged 17 military campaigns to create Egypt’s largest empire extending from northern Syria to the fourth waterfall down the Nile. His victories were marked by the construction of a Festival Hall at the Temple of Amun at Karnak, its entrance carved with a list of conquered territories in Syria, Palestine and Lebanon. On a wall at the back of the Hall was a relief depicting native Egyptian plants like figs, dates, vines and lotus, but also plants from Syria and Palestine like Iris, Arum and Kalanchoe, presumably trophies of war, taken for their medicinal and religious use as well as their natural beauty. Modern historians praise him as a military genius.[12] Later kings built memorial temples fronted by lakes and avenues of trees.

Frescoes painted in the Minoan style and dated to 1500-1450 BCE have been discovered at Tell el-Dab’a (Avaris) confirming a cultural connection between Egypt, Crete, and Thera at the time when Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III were importing foreign plants.[18]

In the reign of Akhenaten (1352-1336 BCE) a garden city was built at el-Amarna in Middle Egypt, the city-centre with sunken gardens which had decorative tiles illustrating individual plants (perhaps a guide to identification) and vineyard, while just outside the city centre was a sacred area, Maru-Aten, with a central lake, avenues of trees, garden beds and temples. Important officials had gardens associated with their houses and workers, who lived on the outskirts of the city, grew vegetables in their own gardens.[11]

Gardens were not only a source of plenty for the afterlife but also for the routine supply of produce for rituals and as food for the priests. In a massive garden complex at the temple of Amun at Heliopolis Rameses III (1186-1155 BCE) planted fruit trees, dates, olives, myrrh, persea, vines, flowers, and pools with waterlilies and papyrus.[19]

The picking and pressing of grapes

Painting from the Theban burial Tomb of official Nakht of the New Kingdom showing the picking and pressing of grapes Adaptation courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Ptolemaic period – 332 BCE to 641 CE

In the 6th century BCE Egypt was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire, the entire 27th Dynasty of Egypt (525-402 BCE) except Petubastis III, being Persian, the Achaemenid kings being granted the title of pharaoh. The 30th Dynasty was the last native ruling dynasty of pharaohs, falling again to the Persians in 343 BCE after the defeat of native Pharaoh, King Nectanebo II.The history of Persian Egypt is thus vdivided into three eras: Achaemenid Egypt (525–404 BC and 343–332 BCE) comprising two intervals of Achaemenid rule divided by an interval of independence and a 27th Dynasty of Egypt (525–404 BCE), also known as the First Egyptian Satrapy. Following the Persian overthrow by Alexander the Great, there was a period of Greek rule that lasted from 332-30 BCE during which a dynasty of 15 Ptolemies reigned before Egypt was annexed by Rome. This was a period when coastal Alexandria was a Mediterranean centre of learning and trade. Palace precincts had gardens as did the large private houses: new crops were introduced and the area under cultivation increased by land reclamation. Ptolemy II, Philadelphus, introduced new crop plants familiar to the Greek settlers such as wheat, vines, olives, garlic and cabbage in two main centres at Memphis and Philadelphia. Land was reclaimed and crops such as cereals, pulses, fodder and vegetables successfully grown, vineyards around a lake just south of Alexandria produced wine that became popular throughout the Mediterranean world. Ptolemy II also built a zoo,[5] and Ptolemy VIII was so fascinated by birdlife that he wrote a treatise about them.[17] There were market-gardens in the city, crops in the Nile delta and some specialized cultivation of papyrus, aromatic plants for the perfume trade, and ornamental plants. Emphasis was on food trees and plants but there were some sacred temple groves like the acacias at Abydos. Mostly the housing was compact with scattered trees and the use of potted plants on roofs and around doorways.[1] The Museion in Alexandria specialised in natural history and geography with an emphasis on mapping and topography. All plant cultivation depended on effective irrigation and this was assisted by the Archimedes screw and the ox-driven water-wheel which became widely used in the Roman period. Romans admired the Egyptian gardens of the period which were portrayed in Roman mosaics and paintings, Egyptian features being emulated in Roman villa gardens of the second century.Design elements

Early gardens were functional with fruit trees, vines, vegetables and herbs, papyrus for paper and flowers grown for their beauty and scent. Sacred groves of trees were established around the royal funerary temples.

Plants collected from Punt

Relief depicting Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

New plant introductions

One of the most elaborate wall reliefs in the Temple of Karnak is known as the ‘botanical garden’, sculpted around 1440 BCE at the time of King Thutmose II. It shows all kinds of plants and birds collected during campaigns in Syria and Palestine. It is one of the first visual indications of botanical specialization.[4]

Economic botany

Gardens and their plants[6][7] were a feature of temples and official buildings where they assumed the role of mystical landcsape, their fruits and aromatic trees planted for the benefit of the gods. Architecture mirrored garden plants – columns the papyrus, lake the primeval ocean, the waters of creation decorated with lotus lilies as beautiful offerings to please the gods.

Many, if not most, of the plants grown in ancient Egyptian gardens had religious or symbolic significance: sycamore fig and tamarisk as resting places for the soul and a manifestation of the goddesses Nut, Isis, and Hathor were planted near tombs and mausoleums. Lotus and papyrus for funeral ritual, poppy and mandrake for rebirth.[13] Persea (Mimusops laurifolia) was a sacred plant of the Sun and said to only tolerate the waters of the Nile while willows were sacred plants of the god Osiris and fequently planted as temple groves. Myrrh and date symbolised fecundity and victory.[15] The multiseeded imported Pomegranate was a symbol of fertility.

Of some interest is the mention by Theophrastus of the rose and gillyflower being cultivated in Egypt: ‘… while all other flowers and sweet herbs are scentless, the myrtles are marvellously fragrant. In that country it is said that the roses, gilliflowers and other flowers are as much as two months ahead of those in our country, and also that they last longer …’ (EP VI.V.iii,5-6).

Includes plants found in wreaths, chaplets and posies.

Ludwig Keimer lists about 40 plants cultivated in ancient Egypt while Baines et al list, in addition to the above, the culinary herbs dill, cumin, marjoram, and rosemary along with Safflower (Carthamnus tinctorius), Tamarix, and Garland Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum coronarium).[21]

Studies of the historical weed flora, including flowers and leaves of weed species used in garlands and bouquets, are used to assess past agricultural practices and historic ecological conditions.

Today’s Egyptian weed flora comprising about 470 species (c. 20% total flora). Archaeological records indicate the introduction of 57 species from Mediterranean, Irano-Turanian and cosmopolitan sources but the times of introduction are undetermined. But records like these indicate the establishment of farming in Egypt more than 7000 years ago.[20]

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

Gardens of Egypt are among the first that are associated with the complex social organization of the Bronze Age cities of Agraria. These cities were made possible by the adoption of agriculture using the fertile soils of the Nile valley. Large communities now had the resources to improve technology and reach beyond their own boundaries in trade, diplomacy, and military conquest. It is the scale of these, and other cities of the Fertile Crescent, that made possible the construction of public parks and gardens and the imposing landscape design that was associated with royal palaces, temples, and tombs. These were the foundations of Western urban design passed on, via the Greco-Roman and Persian civilizations, to the present day. A similar pattern of development would also occur in Asia. In the history of plant science we see not only the increasing sophistication of agriculture at a time when ‘ . . . gardens emerge as distinctly meaningful spaces’,[18][19] but also: the transformation of old animistic medicinal practices into a new academic tradition of medicine associated with high status priests and a writing tradition that entailed the formal training of scribes and acceleration in the process of collective learning; the rise in status of herbs, spices, and medicinal plants, and the initiation of voyages of exploration to access new plant and other resources; increasing development of home and market gardens, avenues and other use of plants and trees in urban design. We see many similarities between the gardens of Egypt and Greece: the plants dedicated to the gods; temples with gardens representing a sacred landscape, the columns of buildings possibly as the trunks of trees and religious concerns with with creation, rebirth and especially death. The Sun was, effectively, a travelling god resembling the Greek myth of the Sun being driven by Apollo in his chariot. Plants were obtained as trophies from trade and military expeditions from the earliest times.Ancient Egyptian believed that animal had sacred supernatural knowledge of the world several were specially immortalized as gods or regarded as communicators with the gods. Candles and animals were used as votive offerings that would deliver messages to the gods. Animals had souls, the heart being the seat of the soul. Animal mummies were quite common as they ensured a transition to the afterlife, burial sites sometimes including animal catacombs. Myrrh and cinnamon were used as part of the stuffing that replaced internal organs, other valuable embalming agents included pistachio resin obtained from Mediterranean countries and sanderac from Africa. Included here were the Ibis of the flooded Nile wetlands (extinct in Egypt since the 19th century). Roman occupation of 380 CE ended mummification, closed the temples, and terminated the world’s longest-lasting civilization.

Egyptian women could occupy senior positions, own property, do business deals and command social respect.

Technologically the Egyptians worked at drainage, irrigation, soil preparation and sometimes constructed terraces?. Greeks added to the intellectual component by studying plants themselves (their description, physiology, reproduction, geography etc.) not only for their religious, medicinal or other utilitarian reason – that is, they created plant science. Romans built on this legacy, enhancing their gardens with statuary and a more in-depth consideration of the principles of landscape as well as adding more practical elements to agriculture and horticulture like budding, grafting, new cultivars, and the first greenhouses. It is likely that most of these elements found expression in the gardens of Ptolemaic Alexandria.[16]

Key points

- first designed and cultivated ornamental domestic gardens c. 2800 BCE, perhaps the oldest known written description of a ‘garden’ dating to the Old Kingdom and a garden planted adjacent to the pyramid of King Sneferu (reigned c. 2613-2589 BCE)

- Egyptian paintings are the first known representations of gardens c. 1400 BCE

- design elements of the Old Kingdom included: colonnades, estate gardens, sacred groves of trees, orchards, pavilions, pools, professional gardeners, vegetable plots and court life

- from the New Kingdom: flower beds, granaries, a ‘botanical garden’ with plant trophies collected from foreign lands, potted plants

- Queen Hatshepsut (1508–1458 BCE) transport of live ‘balled-rooted’ trees

- first painting of the shaduf water lifter, also waterwheels drawn by oxen, and ?extracted by the Archimedes screw

- floors and walls painted with foliage and wildlife, statues, temples and palaces

- use of market gardening – the intensive cultivation of fruit and vegetables

- use of garden villas as country retreats from civic duty

- several plants are also key to Greek and Roman culture and passed on to the Western tradition such as daisies, lilies, roses and olives

- possible first formal representation of a garden layout as a doll’s house sized wooden model in tomb dated c. 2046 – 1995 BCE

Media Gallery

Ancient Egypt: Crash Course World History

CrashCourse – 2012 – 11:54Garden History: 4 Week Online Course with Dr Toby Musgrave

Learning with Experts – 2012 – 5:32First published on the internet – 1 March 2019 . . . revised 22 March 2021 . . . 20 July 2023 – minor revision

Plants collected from Punt Relief depicting Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt Courtesy Wikimedia Commons