Anglo-saxons

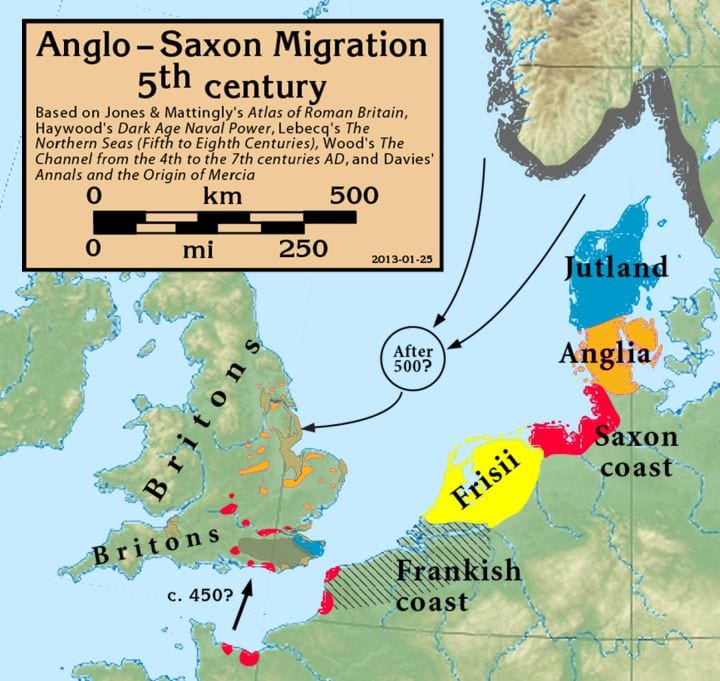

Historian Bede’s suggestion for Germanic migration into Britain writing about 300 yrs after the event

Archeological evidence suggests settlers came from many continental locations

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. Notuncurious. Accessed 24 April 2017

This article is mostly concerned with the socio-political aspects of Anglo-Saxon society. The article on the horticulture of the Early Middle Ages deals with the role of plants over this 600 year period.

Introduction – Anglo-Saxons

Following the decline of the Roman empire and the exodus of Roman garrisons from Britain in 410 CE, and the fall of the Western Roman empire in 476, Europe fell into a period known as the Dark Age. Southern and eastern regions of the island were occupied by Germanic tribal people migrating from continental Europe. During this period, a small number of kingdoms were established, and the native polytheistic and animistic belief systems were steadily replaced by the Christian faith which was administered from Rome. The British Isles were now divided into two regions separated by ethnicity and culture: first, the Celts of Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and England’s northwest and southwest; second, the Anglo-Saxons who, by the year 600, consisted of just seven kingdoms: Mercia, Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Wessex, Sussex, and Kent.

We know little of the 400-year period up to about 800 as literacy, and therefore the written record, was minimal. Historians rely on two major accounts. First, there was the unreliable De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, an account by the monk Gildas (c. 500-c. 700) of the history of the Britons before and during the Saxon invasions. Second was Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the work of another monk, the Venerable Bede (672/3-735), who worked at St Peter’s Benedictine monastery in Anglian Northumbria where he compiled his collection of oral testimonies into a history.

The best historical evidence we have for the Anglo-Saxon period are its physical artefacts and from these we know that pottery and glassmaking ceased, that the removal of coinage hampered trade, and that buildings were once again made of wood rather than stone.

c. 450-800 CE

Anglo-Saxon Britain encompasses a period of about 20 generations extending from around 450 CE through to the Golden Age of the Vikings which lasted from about 700 until the Early Middle Age Norman invasion of 1066. The Christianization of Britain took place from about 500-1000 CE as the Roman Catholic faith spread through Europe (the converted nations referred to as Christendom) and into Britain following the conversion to Christianity in 312 CE of Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (c. 272–337 CE).

Landscape

Much of England supported a mix of villages(a few remnants from Romano-British times) distanced by about two to six miles but also, depending on locality, with interspersed hamlets and farmsteads, many of Celtic origin.

The land was relatively treeless except for a few areas and although clearing for agriculture no doubt occurred there was, by about 800, probably more woodland than had existed in Roman times. However, field expansion probably continued to the early 14th century.[16] Woodland had been managed and trees coppiced for fencing from the Neolithic, being carefully managed from these early times through the Roman and Anglo-Saxon period as timber was used for a host of purposes: houses, ships, farming tools and household utensils and of course as a fuel. Livestock would clear the understorey of woodland to give it the appearance of parkland.

Farming was in ‘strips’ of varying dimensions but generally occupying about half an acre. End-to-end strips together made up a ’furlong’; a ’field’ (or campus) then comprised perhaps several hundred strips, and a village might be supported by, perhaps, 2-3 ‘open’ fields. Ploughing of strips gave rise to a central ridge, strips being separated by a double furrow or grassed area giving rise to a characteristic ‘ridge and furrow ’land pattern. It is however difficult to interpret this pattern in relation to Medieval practices especially as modern ridge and furrow patterns are quite common.[13]

Most of today’s English villages would have been in existence by the 11th century, some dating back to the fifth and sixth centuries but considerably modified over time. The village green probably emerged through this period as did the signature well (on which the people depended), the church and the smithy. Some enclosure probably existed in wooded areas to impound the livestock and keep out the wolves. Itisalsopossible to trace in the landscape the ditches andbanksthat marked the boundaries of great estates. Potentially the Domesday book could have been avaluable source of their record but it only listed land holdings and values, not names of settlements.[14]

Viking insurgency in the ninth century possibly resulted in an increased number of villages although many were simply renamed and the physical evidence of Scandinavian presence is negligable.[15]

Arrival of Christianity

Of special importance to the Middle Ages and beyond, was the unlikely establishment of a new religion, Christianity. This originated in the Middle East with Jesus of Nazareth whose teachings were later compiled into a sacred text, the Bible.

Christianity – like Judaism, Islam, and some other lesser religions (the Abrahamic religions) – was a monotheistic semitic faith that claimed descent from the Judaism of ancient Israelites and worship of the God of Abraham.

Christianity arose out of Judaism, the bible recording oppressed and marginalized people on the fringes of powerful empires, the early Old Testament being about nomadic tribes persecuted by the polytheistic Babylon, and the New Testament an account of similar people, now Christians, under the persecution of Rome with Jesus crucified for his beliefs. The Christian mission was continued by Jesus’s followers (disciples), the most influential being the apostle Paul, who was a Greek-educated orthodox Jew and one-time Roman soldier. Paul travelled widely but was eventually arrested by the Roman authorities. Much of the New Testament consists of fourteen epistles (letters) attributed to Paul, and it is the ideas discussed in Paul’s epistles that have had the greatest influence on the West.

Initial Roman indifference to Christianity was followed by antagonism but took an unusual turn several centuries after Jesus’s death when Emperor Constantine I (c. 272–337 CE) adopted the new religion. With the Edict of Milan in 313 CE Christians were to be treated with respect, and by 325 CE Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman empire. In 330 CE Constantine created an eastern or Byzantine Roman Empire by transferring the capital from Rome to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople after himself). Constantine also instigated the provision of a doctrinal statement of correct belief or orthodoxy, the Nicene Creed, first written in 325 CE and amended in 381 CE.Though, by 476 CE, the western Roman Empire had fallen, the legacy of Christianity flourished, spreading through Latin Europe (Christendom).

Much later, with the Norman occupation of Britain would come new monasteries, impressive abbeys, and further orders of monks – the Augustinians (est. in England c.1250), Cistercians (est. 1128), Carthusians (1173), Dominicans (est. 1221), Franciscans (est. 1224) and those orders associated with the religious Crusades (1095-1291) – the Knights of St John of Jerusalem (est. c. 1190) and the Knights Templar (est. 1154). Orders of nun’s also practiced in convents and mixed communities. Hospitals were either independent establishments, generally staffed by nuns and monks, or part of the monasteries themselves, both of these usually included courtyards and gardens.

Christianity and other monotheistic religions cleared away the complexities and confusion resulting from polytheism and animistic beliefs. Romans had, for example, absorbed the gods of conquered peoples into a vast pantheon. Monotheism identified a single god and, through a holy book, revealed god’s teachings on the Creation, human conduct, the spiritual world, life after death, and the future of humanity. Religion was the medium for social rites of passage, and it underpinned the education system. Collectively these were powerful forces in daily life that had a profound influence on the Middle Ages and beyond not least of which was the Christian calendar which places the origin of Judaism to a covenant between god and Abraham in 1812 BCE, Christianity to the birth of Jesus in the year 0, and Islam to the prophet Mohammed’s teachings in the Quran beginning around 610 CE.

There was, at this time, a transition between pagan Cetic ideas and the new models of the Roman Catholic Church that would later be replaced by Norman traditions. Notable among the clerics of the time was St Augustine (354 – 430 CE) whose Neo-Platonic writings had a profound influence on the Medieval European Church, especially his ideas published in the book City of God (the Roman Catholic Church) which would replace this earthly world of toil and cares.

The first Saxon king to convert to Christianity was King Ethelbert (c. 560-616) of Kent who, after receiving a papal mission from Rome, converted in 600. The other kings followed over the next 80 years as papal Christianity was centred on Canterbury and York. However, the Welsh, Irish, and Gaelic Abbey of Iona followed their own distinctive Celtic form of worship. England, at the Synod (Council) of Whitby in 664, called by King Oswald’s brother Oswy (612-670), decided to follow the Church of Rome, thus severing the connection with the Celtic church and joining mainstream European Roman Catholicism.

Kings and powerful gave financial and other support to monasteries which would, in turn, bless and legitimate their rule. In this way monasteries, also repositories of learning, gathered both wealth and influence.

By 550 CE native Britons in the eastern part of the country had become an underclass as they fell into servitude, the new invaders now occupying seven distinct kingdoms: Mercia, Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Wessex, Sussex and Kent (see map). It was left to the burgeoning Christianity to take control of the process of reconstruction and as the power of the Church increased, monasteries were built along with cathedrals and abbeys. Around these buildings land was cleared, ploughed, and farmed to support the nearby communities. In addition to the cereals grown were apples, pears, mulberries and nuts. Material luxuries like jewellery and other objects made from precious metals also art work, including painstakingly crafted illuminated manuscripts, now became part of the church.

An excellent impression of the monasteries of the day can be obtained from an idealised ground-plan drawn up in 815-820 AD for the Abbey of St Gall in Switzerland, the only surviving major architectural drawing from the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–). The plan shows a vegetable garden with beds for 18 different vegetables and a gardeners house and tool shed, also a separate physic garden.[6] Benedictine monks at this time would have been engaged in pastoral care, providing food, minding the sick and caring for the needy.

Ground-plans of Anglo-Saxon churches in southern England were based on the traditional Roman basilica while in the north the Celtic influence produced narrow, high, and rectangular churches with doors on the sides. In spite of Roman Church authority the Celtic style was used for parish churches in England, only later the Normans rebuilding many of the earlier Saxon churches in the Norman style. Ceorls lived in extended family groups and worked selected plots of land which were part of large blocks of common land: they lived in farmers crofts which had small gardens for food and herbs, kale and colewort being especially popular at the time.[4]

Western coast

Following the Roman exodus from Britain there was a dark age of about 200 years that lasted from c. 410 CE until about 600 CE. During this time the most comprehensive, though unreliable, written record of events was that of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s (c. 1095 – c. 1155) History of the Kings of Britain or De gestis Britonum or Historia Regum Britanniae. This was written some 600 years after the events it describes and with much of his account further embellished in the 14th and 15th centuries. This was the mythical time of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table who fought the Anglo-Saxon invaders from across the North Sea.

History has been primarily concerned with the internal conflict of these times between the Britons and Anglo-Saxons while the archaeological evidence now suggests that this was more a process of assimilation, intermarriage, and integration, and that this period might be better understood in terms of the east coast settlement of Germanic peoples while the west coast Britons were influenced more by the nations of Europe’s south Atlantic coast and Mediterranean.

Tintagel was a small island on the Cornish coast, probably a trading hub for the Roman tin that was mined locally. This was one of only three major sources of tin in Western Europe, the metal needed to produce the bronze weapons and tools.

Tintagel was where Arthur is assumed to have lived and here archaeologists have found the footings of masonry buildings and artefacts, such as pottery, sourced from as far away as Turkey, indicating that this was a local seat of power. These buildings contrasted with the wood and brush dwellings found elsewhere in the country at this time.

South & East

Early Anglo-Saxon history (410–660) entails the migration from the continent to Britain of Angles, Franks, Frisii, Goths, Saxons, Lombards, Suebi, and Vandals, who were being threatened by east European tribal Alans, Avars, Bulgars, Huns, and Slavs. By around 500 CE Anglo-Saxons, possibly numbering 20,000 to 100,000, were established in southern and eastern England although outnumbered about four to one by the indigenous Britons some of whom c. 550 crossed the English Channel, establishing a colony in Brittany (Armoracia) while the remaining population was gradually assimilated into the dominant Germanic culture.

Across Europe the first Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne (742–814 CE) initiated a ‘Carolingian Renaissance’ which sought to revive the industrial vibrancy of the Roman culture and economy. Part of this cultural revival was encouragement for the nurturing of plants and gardens in major cities throughout Christendom. With the Anglo-Saxons came a landed gentry with manorial estates managed by ‘lords’ and land partitioned into parishes, each with its parish priest and church.

At the time of the Roman evacuation some Roman soldiers would have remained. From the continent would have been some administrative officials and a few Christian clerics but south of Hadrian’s wall most people were descendants of the Iron age people who had occupied the country before the Roman invasion.

There arose a small ruling Romano-British (a civic not an ethnic designation) elite who called themselves ‘Roman’ and who in all likelihood spoke and wrote in Latin. The ethnically diverse Anglo-Saxons from north-west Europe who entered and assume control of the country introduced the precursor of what is now the world’s most widely-spoken language, English.[9] By the 490s the Romano-British elite was being displaced as was the Latin they spoke as the Germanic invaders (Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians and others) who assumed control.

By the 9th century the Anglo-Saxons or ‘English people’ denoted those of largely Germanic origin and with an emerging English language.[10]

On the continent with the withdrawal of Roman influence local patricians withdrew to villa estates which became self-sufficient economic units (French ville-town). It was this form of social organisation that set the precedent for the English landed gentry.[11]

Monk Bede, who died in 735 CE, bequeathed the major historical document of the period, the monumental Ecclesiastical History of the English People. When ascribing dates to events he used ‘the year of Our Lord (anno domini, AD)’ which, along with the international dating system the Common Era (CE) starting from the presumed date of the birth of Christ, can be largely ascribed to Bede. Of more secular appeal and written in Germanic language (not Latin as used by Bede) there is the epic poem Beowulf, written in about the 8th to 11th centuries but probably transcribed from an oral tradition dating back to at least 600CE. It is set in southern Scandinavia and tells of loyalty to leaders, warrior skills and bravery against massive odds. Though its historical value is limited it does give us an insight into the social and political ethos of the day.

By the time of the Norman invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066, after the Viking uniting of the East under the Danelaw, Anglo-Saxon England had a more or less uniform centralised administration that could not be matched in Italy, Spain or France. It gave the Normans a sound base from which to launch their government, monasteries and castles.[12]

In 700 CE Arab caliphs in Damascus ruled an empire that stretched from Portugal to Pakistan.

Germanic peoples

Almost as soon as the Romans left the islands the new Anglo-Saxon occupation began in about 450 CE. Famous English Historian, the monk Bede (c. 672–735) in his most famous work Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) recognises three invading Germanic peoples: Angles (from present-day Schleswig-Holstein who probably established the kingdoms of Northumbria, East Anglia and Mercia in the north-east segment of England extending from about the Firth of Forth south to Harwich); Saxons (from Lower Saxony and the Lowlands or present-day Netherlands); and Jutes (mostly from the Jutland peninsula of modern Denmark who settling south of the Thames) although other peoples may have been involved.

At the same time as the Roman garrisons withdrew there was in influx of Jutes and the Frisians from Denmark who retained their own culture and Germanic language, now referred to as the Old English.Coming to us from this time is the word wyrttun or lectun related to the garden[1]and wyrt used for plants in general and with an Indo-European root, changed in Middle English to wort as in liverwort or bladderwort, also referring to a vegetable garden or orchard. These Germanic Anglo-Saxons were farmers and warriors who used timber, not stone, as a construction material. Roman ways were forgotten as pottery and glass-making ceased, coinage was abandoned, trade declined and Roman buildings and infrastructure crumbled: by the seventh century a former prosperous Roman province had changed into a fiefdom of haggling warlords.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had been superimposed on a former Celtic world that now remained in the West: like the tribes to the north of Hadrian’s Wall they had never succumbed to Roman rule It was these people who became known as the Britons whose ancestry dated back to the earliest occupation of the island after the Last Glacial Maximum, mostly by people from the Iberian Peninsula.

Food & housing

The everyday Anglo-Saxon lived on a diet of bread and vegetable stew flavoured with herbs like thyme, nettle, and fennel. Meat being was reserved for special occasions and the drink of choice was the mildly alcoholic honey-based beverage called mead, similar to beer.

The buildings were mostly of a Grubenhäuser style, similar to those of Germanic tribes on the continent, with a pit dug below the house covered by floorboards and with supporting posts. Grubenhäuser were used to store grain and food, also the place to produce tools and for domestic dwellings. Communities would have a larger central building for meetings, feasts and other social rituals. A family Grubenhäus would probably last for a single generation before a new one was constructed.

Social structure

Anglo-Saxon society was hierarchically structured into nobles, ealdormen, ceorls then serfs. Ceorls (churls, lowest rank of freeman, hence ‘churlish’) were the peasants and they were a segment of society sometimes contrasted with the thegns (lords).

Land ownership

The lords built up their landholdings into fortified manor houses or estates. On these manorial estates gardens were sometimes constructed along with a church (often built on a former pagan site of spiritual significance), cemetery and a small community of people.

Land was becoming ordered into bounded parishes, many of today’s parish boundaries probably originating as boundaries of these early Saxon manors.

In 2019 a 1400-year-old royal burial tomb was discovered at Prittlewell about 60 km east of London, this being the earliest Christian royal burial (known as the ‘Prittlewell Prince’) ever found in Britain and containing goods probably obtained from as far away as Syria and Sri Lanka.

Farming

Most people would have worked on the land. Farms of the period grew wheat, barley, rye, oats, beans, turnips, carrots, leeks and onions. And there were sheep, cows, goats, pigs, horses, chickens, ducks and geese. Archaeologists divide this period into three smaller periods of time:

Gardens

Emperor Charlemagne & the Capitulare de Villis

Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 AD by Pope Leo III. Through this act Charlemagne became the first emperor of Western Europe since the Roman collapse three centuries before. Charlemagne developed a Christian empire that stretched across Western Europe and during his imperial rule Europe was to develop a common identity of art, religion, and culture (the ’Carolingian Renaissance’) introduced through the medium of the Roman Catholic Church.

Of greatest horticultural import during his imperial reign was the drawing up of the Capitulare de Villis (On the Management of Estates). With this decree Charlemagne attempted to revive a Roman villa-type garden economy using the medieval Anglo-Saxon tradition of manorial estates. This document insisted that every city should have a garden based on its detailed recommendations.

The Capitulary lists over 70 species of flowers, herbs and vegetables and 16 kinds of fruit and nuts: it represents an excellent synoptic account of vegetables, fruits, and herbs of the day:

70. It is our wish that they shall have in their gardens all kinds of plants: lily, roses, fenugreek, costmary, sage, rue, southernwood, cucumbers, pumpkins, gourds, kidney-bean, cumin, rosemary, caraway, chick-pea, squill, gladiolus, tarragon, anise, colocynth, chicory, ammi, sesili, lettuces, spider’s foot, rocket salad, garden cress, burdock, penny-royal, hemlock, parsley, celery, lovage, juniper, dill, sweet fennel, endive, dittany, white mustard, summer savory, water mint, garden mint, wild mint, tansy, catnip, centaury, garden poppy, beets, hazelwort, marshmallows, mallows, carrots, parsnip, orach, spinach, kohlrabi, cabbages, onions, chives, leeks, radishes, shallots, cibols, garlic, madder, teazles, broad beans, peas, coriander, chervil, capers, clary. And the gardener shall have house-leeks growing on his house. As for trees, it is our wish that they shall have various kinds of apple, pear, plum, sorb, medlar, chestnut and peach; quince, hazel, almond, mulberry, laurel, pine, fig, nut and cherry trees of various kinds. The names of apples are: gozmaringa, geroldinga, crevedella, spirauca; there are sweet ones, bitter ones, those that keep well, those that are to be eaten straightaway, and early ones. Of pears they are to have three or four kinds, those that keep well, sweet ones, cooking pears and the late-ripening ones.[5]

Roman plants

Among the medicinal plants imported by the Romans were Fennel Foeniculum vulgare, Ground-elder Aegopodium podagraria, and Wormwood Artemisia absinthium, which were now finding their way out of the gardens and into the countryside. Sweet and sour cherries survived neglect and Roman introductions like dill, lettuce, kale, radish and beet were all cultivated. Some Roman-introduced fruits and vegetables may have lapsed into disuse.

Anglo-Saxon names for plants, weekdays, and festivals

A list of 200 widespread plants was compiled by Aelfric of Eynsham[17], the Roman introductions possibly indicated by the similarity of the Anglo-Saxon words to their Latin names e.g. Petroselinum-Petersilie-Parsley, Ruta-Rude-Rue. Practical use took precedence over beauty and this is reflected in their Anglo-Saxon names which, from the 10-12th centuries, were given Christian equivalents.[7]

Many common Anglo-Saxon words remain in the English language celebrating weekdays and festivals: Wednesday (Woden – supreme Saxon deity), Tuesday (Tiw – god of law and order), Thursday (Thunor, Thor – god of thunder), Friday (Freya – goddess of fertility), Easter (Eostre – goddess of spring or dawn), Yule (a 12 day Anglo-Saxon festival of Géol).

Timeline

410 – Alaric I, first king of the Visigoths from 395–410 sacks Rome. Roman garrisons leave Britain

476 – soldier-statesman and former barbarian Flavius Odoacer (c. 433–493 CE) deposes child emperor Romulus Augustulus to become King of Italy from 476 to 493 CE (defers to emperor Zeno in Constantinople). A date that marks the end of the Western Roman Empire 563 –St Columba founds Iona Abbey

595 – Canterbury becomes centre of the Christian mission of Pope Gregory I

c. 600 – Saxon King Ethelbert converts to Christianity

604 – St Augustine founds St Paul’s Cathedral

635 – St Aidan founds Lindisfarne Abbey

664 – Synod of Whitby unifies the Church under mainstream European Roman Catholic Christianity

793 – Lindisfarne plundered by Viking raiders

871 – Alfred King of Wessex

878 – Alfred defeats Vikings at the Battle of Edington

991 – King Ethelred pays protection tax to Vikings marking the initiation of Danelaw

1013 – King Forkbeard seizes Saxon throne as Ethelred II flees to Normandy

1014 – Ethelred II reclaims throne on Forkbeard’s death

1016 – Ethelred II dies and Cnut now rules the country, uniting England, Denmark and Norway into a trading bloc

1042 – Edward the Confessor becomes king; Vikings leave England

1053 – Godwin, Earl of Essex dies

1054 – The Great Schism (East–West Schism) was the break between the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Churches resulting from both theological and political differences that had developed during the preceding centuries

1066 – Edward dies and is succeeded by Harold II, last Anglo-Saxon king

1066 – William of Normandy defeats Hariold II at the Battle of Hastings

Sustainability analysis

During the period of Roman occupation Britain was linked in trade, technology and custom to the sophisticated social organisation of the Roman Empire.

Anglo-Saxon England became a collection of warring kingdoms as Roman infrastructure deteriorated. However, Anglo-Saxon Britain was beginning to define the character of future social structures and patterns of land ownership.

European Society of the Early Middle Ages was based on the Feudal concept of the ‘lord’ (French ‘seigneur) reminiscent of structures found in late classical society. This was evident during Charlemagne’s reign when land grants contributed to manorialism and vassalage, the vassal giving the lord labour and military support in return for privileges that might include a grant of land (a fiefdom).

In the 7th century a degree of job specialisation arose in line with an increase in population during the Middle Saxon period. as economy improved. There was now a proliferation of towns and a greater division of labour as the numbers of craftsmen increased.

Plants featured in Anglo-Saxon life through the daily need for food. Early Anglo-Saxon settlements were initially built on the light soils of river valleys and were accompanied by a fall in population after the Roman occupation while the farming at this time was very similar to that of the Iron Age and Roman periods.

Gardens, it seems, took up only a small part of the landscape and daily life being rarely mentioned in official documents like land grants and wills. Plant diversity was probably greatest in the monastic physic gardens.

Estimates of the population number and the relative proportions of Britons and Anglo-Saxons, based on archaeology, are equivocal and genetics is confounded by the difficulty of obtaining a clear genetic signature. Cunliffe suggests that the population of Britain in the mid 5th century had fallen to about two million with the proportion of immigrants in southeast England making up 10-20% of the population.[8]

Maritime shipping would have plied its trade across the English Channel to Armoricia (Brittany) and up the English east coast while archaeological excavation of pottery indicates an active Atlantic sea route extending round the Irish Sea. Technology: axe; fire; domestic, animals.

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

MEDIEVAL PERIOD

Early Middle Ages - 400-1000

High Middle Ages - 1000-1300

Late Middle Ages - 1300-1500

BRITISH MONARCHS

SAXON - 802-1066

DANE (Viking) = D

Egbert - 802-839 - Wessex

Æthelwulf - 839-856

Æthelbald - 856-860

Æthelbert - 860-866

Æthelred I - 866-871

Alfred-the-Great - 871-899

Edward the Elder - 899-924

Athelstan - 924-939

Ælfweard - 924

Edmund I the Elder - 939-946

Eadred - 946-955

Eadwig the All Fair - 955-959

Edgar I - the Peaceful - 959-975

Edward the Martyr - 975-978

Æthelred II - Unready - 978-1013

Sweyn I Forkbeard - 1013-1014D

Æthelred II Unready - 1014-1016

Edmund Ironside - 1016

Canute the Great 1016-1035 - D

Harold Harefoot - 1035-1040 - D

Harthacanute - 1040-1042 - D

Edward t'e Confessor 1042-1066

Harold II - 1066

Edgar Ætheling - 1066

NORMAN - 1066-1154

William I - 1066-1087

William II - 1087-1100

Henry I – 1100-1135

Stephen of Blois – 1135-1154

PLANTAGENET - 1154-1485

Henry II – 1154-1189

Richard I Lionheart – 1189-1199

John Lackland – 1199-1216

Henry III – 1216-1272

Edw' I Longshanks – 1272-1307

Edw' II of Carnarvon - 1307-1327

Edward III – 1327-1377

Richard II – 1377-1399

Henry IV – 1399-1413

Henry V – 1413-1422

Henry VI – 1422-1461

Edward IV - 1461-1483

Edward V - 1483

Richard III - 1483-1485

TUDOR - 1485-1603

Henry VII – 1485-1505

Henry VIII – 1509-1547

Edward VI – 1547-1553

Lady Jane Grey/Dudley – 1553

Mary I/Mary Tudor – 1553-1558

Elizabeth I – 1558-1603

STUART - 1603-1714

James I – 1603-1625

Charles I - 1625-1649

Civil War – 1642-1651

Commonwealth - 1649-1653

Protectorate – 1653-1659

Charles II – 1660-1685

James II (VII Scotl'd) -1685-1688

Mary & William - 1688-1694

William of Orange – 1694-1702

Anne – 1702-1714

HANOVER - 1714-1901

George 1 – 1714-1727

George II – 1727-1760

George III – 1760-1820

George IV – 1820-1830

William IV – 1830-1837

Victoria – 1837-1901

SAXE-COB' GOTHA 1901-1910

Edward VII - 1901-1910

WINDSOR – 1910->

George V – 1910-1936

Edward VIII – 1936

George VI – 1936-1952

Elizabeth II – 1953->