Josephine Bonaparte

Josephine de Beauharnais – 1763-1814

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

Josephine Beauharnais (1763-1814), wife of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, lived through the peak of Enlightenment history when Britain and France were the major European powers vying for ascendancy, when Enlightenment voyages of scientific exploration were to bring back treasures and stories from the South Seas, and when Australia would be finally settled by the British. Above all she epitomised the Botanophilia that gripped European high society at this time.

As first Empress of France Josephine was a key figure of the Enlightenment. As the first Empress of France she was a major European trend-setter in the social obsession with plants that characterises this period in history. Josephine’s fascination with natural history and plants was insatiable and she indulged this interest at her two estates, the Château de Malmaison in Paris, which she had bought on borrowed money in 1798, and the Château Navarre in Normandy which had been given to her by Napoleon after their divorce in 1810 (she had not borne him any children).[1] For about 15 years under her keen eye at Malmaison one of Europe’s finest collections of exotic plants was amassed including not only the world’s most extensive collection of roses but also her prized treasures from around the world but especially those from ‘Nouvelle Hollande’. To celebrate her plants she also commissioned some of the world’s most accomplished botanical art.

Politics & society

Napoleon and Empress Josephine routinely entertained the infuential intelligentsia of the day including the new and highly respected Enlightenment scientists. This was a way of keeping informed of political and social concerns and thinking about the latest issues as well as staying ahead of the social gossip. It was a form of social networking that we also see practiced by Joseph Banks. Josephine was the most celebrated hostess of her age – fashion’s leading figure, delighting Parisian society with her galas, dinners and balls … her dinnerware at Malmaison proudly depicted Australian exotica. At Malmaison the couple regularly entertained scientists and artists along with the inevitable politicians and military. In her own dealings Josephine respected the Enlightenment code of not allowing politics to intrude on her personal interests so, in spite of France’s parlous relationship with Britain, she maintained regular communication with her British gardening friends.

Josephine & Napoleon

Both Napoleon and socialite Josephine were expatriots. Napoleon was a Corsican and Josephine the daughter of a wealthy creole sugar plantation owner from Martinique in the West Indies. She had moved to Paris with her first husband who was guillotined in the Reign of Terror when she was imprisoned but soon released after the death of Robespierre. She had two children from this married, a son Eugene and daughter aptly named Hortense (a name derived from the Latin meaning ‘gardener”) who married Napoleon’s brother Louis in 1802.

Natural history & botanophilia

Josephine was familiar with botanical names and the latest botanical literature, her deep interest in botany exasperating guests at her estates as she regaled them with a torrent of Latin plant names and ceaseless botanical chatter.

Josephine’s fascination with natural science and New Holland was shared by Napoleon, although writers have understandably emphasized Napoleon’s military exploits over his scientific interests. When aged 15 and a student at the Ecole Militaire in Paris, Napoleon had made an unsuccessful application to join the La Pérouse expedition to the South Seas, and when 26 he had been elected a member of the mathematical section of the newly formed Institut National (the Académie des Sciences before the French Revolution). After the Revolution in 1789 science was strongly encouraged and the number of professorships at the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle was increased to 12, three of which were botanists, and Napoleon continued to support this initiative. Included in his reading were Cook’s publications and even botany text books.[9]

A few months after assuming the position of First Consul in 1799, a title he held until 1804, Napoleon authorized Baudin’s scientific expedition to Nouvelle Hollande, an expedition that was to provide Malmaison with many of its antipodean plant prizes.

Between 1798 to 1801 Napoleon mounted an expedition to Egypt as part of his campaign of Revolutionary wars. Enlightenment interests meant that the advancement of knowledge and science remained political priorities. He included many ‘savants’ exploring all aspects of Egyptian natural and other history. This was published as Description de l’Égypte in many and lavish forms from 1809 to 1829. In 23 volumes and over 1000 plates it included the work of over 160 scientists and vast numbers of engravers and artists. It was the most comprehensive study of Egypt before the deciphering of hieroglyphics.

Botanophilia was at its height. In 1801, although France and Britain were at war relations were thawing in the year before the Treaty of Amiens and Josephine wrote to the plenipotentiary in London asking if George III could be persuaded to send her some plants from ‘son beau jardin de Kew’, just one letter of an extensive correspondence she built up on the plants and animals at Malmaison.[12] Australian plants at Kew were not doted on by George III and British royalty in the way they were in France: the 16 Banksia, 11 Acacia and 4 Lasiopetalum growing at Kew in 1806 (mentioned in a Robert Brown letter) did not get published and nor did the 70 Australian plants recorded as growing, in 1802, in the present-day Glasnevin Botanic Gardens in Ireland. Josephine eventually published 71 Australian plants in her books on Malmaison even though many of those grown were not mentioned, including some eucalypts and casuarinas.[13]

Like Britain’s Chelsea Physic garden (est. 1673, see Philip Miller) and Oxford Physic Garden (est. 1632) France had its iconic physic gardens, dating back earlier than those in Britain as the botanical and horticultural Renaissance had passed across Europe from Mediterranean Italy to the north-west Europe, reaching France before crossing the Channel. The Jardin des plantes de Montpellier on the Mediterranean coast of France was established in 1593 as the oldest Botanic garden in France and it was associated with the university at Montpellier and serving as a model for the Jardin des Plantes in central Paris which was established 33 years later in 1626. It was Josephine’s intention to surpass these two gardens in both content and reputation.

Château de Malmaison

Château de Malmaison was situated on the Banks of the Seine just one hour’s drive by carriage from central Paris. Among the attractions at the 726 ha estate were a heated orangery and several hothouses including a state-of-the-art 50 m long hothouse, her Grande Serre Chaud (superior to that at the Museum of Natural History) heated by 12 large charcoal stoves – and here she cosseted many of her Australian plants.

At first she asked André Thouin (1747-1824) (who had a good working relationship to the private collection of Jacques-Martin Cels and Louis-Claude Noisette (1772-1849) to assist her in expanding her collection of exotic plants. Noisette was a botanist and agronomist, son of Joseph Noisette, gardener to the Count of Provence, the future Louis XVIII. Louis founded in 1806, along with his brothers, a botanical facility to assemble ornamental plant rarities but is perhaps best known for his outstanding collection of roses.[20]

Botanical exploration

Josephine took great pride in her much-envied collections of new plant introductions from distant lands – gathered from Humboldt and Bonpland expeditions to South America and Mexico, Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, Baudin’s expedition to Australia (1800-1803, see Baudin expedition), also purchased and exchanged with other gardens of Europe. When French troops occupied German states 600 plants were sent to her from Berlin in 1806, and in 1809 she received 800 plants from the Palace at Schönbrunn, sending the director a ring worth 2,000 francs in compensation.[6] New Holland plants were acquired from many sources including the Baudin expedition, the Lee & Kennedy Nursery in London, the nursery of Jaques Martin Cels outside Paris, and as gifts from botanists and admirers around the world, including Joseph Banks.[8] Malmaison itself had a nursery where plants, including those from New Holland, were dispatched to other gardens around France.

Rose collection

Most of Josephine’s rose collection was assembled in the years 1804 to 1810 and was a factor in the upsurge in rose breeding that occurred in France in the first half of the century, mostly associated with the names Vilmorin and the Freemason and physiocrat Jacques-Louis Descemet (1761-1839) the foremost rose breeder of France, but also associated with the rose nurseries of Du Pont I in France, Van Eeeden of Holland, and Lee & Kennedy of Britain. Her horticultural advisor on roses was Andre Dupont.

Josephine’s magnificent rose garden included lawns, streams, and a Temple D’Amour. Her French advisor André Dupont took special care of her favourite collection of 150 different Gallica roses, he was the director of the Jardins de Luxembourg in Paris where there was another famous collection of roses. She grew the roses in pots and together they constituted the most famous collection in Europe, numbering between 500 and 800 species and varieties at the time of her death. Malmaison was the birthplace of the tea rose.

What made Josephine’s rose collection especially compelling was the botanical illustration that she commissioned from Pierre-Joseph Redouté, court painter to Queen Marie-Antoinette, and arguably the most accomplished botanical artist of all time. His superlative three-volume Les Roses (1817-1824) was completed after Josephine’s death, the plant descriptions by the botanist Claude-Antoine Thory. This collection of 168 plates became a reference work and masterpiece of the print medium, his painting of the cultivar ‘Blush Noisette’ singled out as one of the world’s greatest ever works of botanical illustration.[15]

Josephine was the premier rosarian of the nineteenth century producing the first of many histories of the rose and staging the world’s first rose exhibition in 1810. She also popularised the use of vernacular names for the horticultural varieties (cultivars) as a relief from the pompous Latin ones. As France’s first Empress she set the fashionable social agenda as in both France and Britain rose collections were quickly assembled and bitter social rivalries and jealousies were played out on the grand estates of the wealthy. In France, Josephine’s closest rival was the Countess of Bougainville.[15]

Much of her collection survived the allied occupation of Paris in 1815. Even with a naval blockade in place the British Admiralty allowed free passage to the Kennedy and Lee nursery assignments of China roses to Malmaison, and Kennedy himself assisted with the design of the garden. One draft plan (never used) apparently closely resembled the Union Jack.[15] Meanwhile Descemet’s fortunes declined with the fall of the empire. Bankrupt he went into exile in Russia, settling in Odessa where he established a botanic garden with himself as director and is noted for the introduction of many exotic trees to Crimea. The Vilmorin name persists in horticulture, the company operating from an estate that was a former hunting lodge of Louis XIV, and noted for its gardens and arboretum.

The rose is the single most popular ornamental plant of all time. It has always been a hallmarker of social status in an aristocratic tradition of rose appreciation that dates back to the ancient royal gardens of Egypt and the villa gardens of Greece and Rome. Economically the rose was the most important ornamental plant in France and no doubt elsewhere in Europe. Josephine defined a horticultural era through this plant alone.

Menagerie

Josephine’s menagerie (the aristocratic or royal tradition of exotic animal collections dating back to antiquity but reaching its height at Versailles in the reign of Louis XIV from 1643-1715) proudly displayed exotica from Nouvelle Hollande including emus, kangaroos and black swans.[4] And from other climes came ostriches, zebras, gazelles, antelopes, llamas, chamois and a seal. Combining animal and plant curiosities was a tradition passed on to public botanic gardens, the collection of animal trophies being a precursor to the modern zoo and a probable source of the apparently strange binomial ‘zoological garden’. It was in this tradition, for example, that a menagerie was established in the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne (and other Australian public gardens) under the Directorship of Ferdinand Mueller although like many similar animal collections on display in public gardens was later removed. Royal collections of exotic animals date back to antiquity. The Tower of London was constructed by Norman conqueror William I in 1078 and played a part in the history of zoos. The Royal Menagerie is first referenced during the reign of Henry III (1207-1272) who received three leopards from Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III in 1235. Lions were especially popular. A polar bear is recorded in 1251 drawing attention when it went fishing in the Thames and in 1254 an elephant house was constructed at the Tower while the lions wee confined to the Lion Tower. The royal court of James I (1567-1625) enjoyed animal baiting viewing the action from a specially constructed platform as dogs, bears and lions fought to the death below. Animals were among the prized diplomatic gifts exchanged between royalty at this time and by the 18th century the menagerie had been opened to the public: admission of three half-pence was waived if a cat or dog was brought to feed the lions. In 1828 there were over 280 animals representing at least 60 species. Finally in 1832 following several escapes, when the animals attacked both staff and visitors, the animals were transferred to Regent Park Zoo by the Duke of Wellington who was constable of the Tower.[18]

The British connection

Ignoring the politics of the day Josephine insisted on laying out her garden at Malmaison á l’Anglais, the English Romantic style that was the fashionable landscape style of the day by deploying sinuous paths, trees and shrubs grouped in island beds combined with water features and flower beds, all in a park-like setting. In Australia this style is best represented at the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne and the adjacent Government House.

To achieve her goal she employed two Scotsmen, Thomas Blaikie (1750-1838), and Alexander Howatson. Blaikie’s story is similar to those of other social gardeners of the day. He had travelled to France as a botanical collector but set himself up in Paris as a landscaper working first in 1776 on the gardens at Bagatelle, Monceau and le Petit Trianon and subsequently at Malmaison where he worked with Howatson. His time employed by the French aristocracy is recorded in Francis Birrell’s The Diary of a Scotch Gardener at the French Court at the End of the Eighteenth Century.[2] Among Blaikie’s recollections are a breakfast with Joseph Banks in 1775 and then, in 1776, thanks to James Lee he was employed by the Comte de Lauragais on an estate in Normandy, the Comte introducing him to further commissions from the French aristocracy. Blaikie was a keen contributor to Loudon’s Gardener’s Magazine ( see Horticultural literature).[3]

Josephine imported more and more plants and seed, favouring those from New Holland, and most coming from the Vineyard Nursery of Lee and Kennedy in London. From Britain Josephine also received gifts of seed from Joseph Banks while James Smith sent her seed from Botany Bay.[11] Lee had visited her himself and, although England and France were at war the plant shipments were permitted to pass through the British naval blockade unimpeded, her purchases from the nursery pushing the limits of her allowed budget. With the revival of war between France and Britain, John Kennedy had a special permit to come and go to the Continent, advising the Empress on the collection she was forming at Malmaison. There were setbacks: in 1804 she complained in a letter that shipments of seeds had been captured and detained; but in 1811 her expenditures with the firm blew out to £700. All this attention and expense dedicated to France’s political enemy would have tested Napoleon’s patience as she continued an amicable exchange of plants with Joseph Banks (Banks is known to have sent her roses and plants for her collection). Nurserymen Lee & Kennedy shared with her in 1803 the cost of sponsoring a collector trained at Edinburgh Botanic Gardens, Scotsman James Niven (?1774-1827) on a trip to the Cape of Good Hope in return for some of his botanical spoils.[5] It is a measure of her specialist interest and Niven’s tenacity that her collection of Erica (heath), one of her favourite genera, rose from 50 species in 1805 to 132 species in 1810.[7]

The New Holland connection

French achievements in Nouvelle Hollande were impressive: the first complete continental coastal map of Australia; the first scientific descriptions of the eucalypt, wombat, platypus and emu; the scientific proceeds of the French voyages of scientific exploration, especially the Baudin expedition which was the largest and most ambitious of these expeditions, – out of these flowed, for example, the first extended account of the continent’s plants, Labillardière’s 7 kg Novae Hollandiae Plantarum Specimen published between 1804 and 1807 which contained 265 black and white engravings by artist Pierre Antoine Poiteau (1766-1854).

Redouté’s florilegium Jardin de Malmaison

Labillardière’s work was published at the same time as Josephine’s commissioned work Jardin de Malmaison (1803) illustrated in colour by the celebrated Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Josephine was determined to employ the world’s greatest botanist for the description of plants growing in her hothouses and the descriptions were to be illustrated by the world’s most accomplished botanical artist. She chose as botanist the illustrious Étienne Pierre Ventenat who was Lycée professor in charge of the Pantheon library and a member of L’Institut. His book Description des Plantes Nouvelles at Peu Connues Cultivées dans le Jardin de J.M. Cels which described plants in the garden of Jacques Martin Cels at Montrouge just outside Paris had gained wide recognition, in part because it contained 81 black and white drawings by Redouté, eight by Redouté’s brother Henri Joseph Redouté (eleven of them were plants returned from Australia by Labillardière – species of wattles, bottlebrush, paperbarks and hakeas). Ventenat now worked closely with Redouté for several years describing and illustrating the plants growing in the park and hothouses at Malmaison. After the death of Ventenat in 1808 Aimé Bonpland took over his work, holding the combined position of Botanist and Conservator at Malmaison until 1814 and further botanical descriptions of plants growing at Malmaison were published. Bonpland in 1814 mentions seed of Eucalyptus diversifolia sent to Toulon Botanic Garden on the Cote d’Azur where it thrived, and de Candolle had described Acacia paradoxa, Prickly Moses, from plants cultivated in the Montpelier Jardin des Plantes in the south. Wattles and eucalypts were soon to become a spreading menace not only in this region but also in Corsica, Algeria, South Africa and St Helena.[14]

Redouté would also produce an 8 volume work on lilies Les Liliacees (1802–1816) and more than 100 colour plates of the Australian flora. Etienne-Pierre Ventenat, librarian of the Pantheon in Paris, now named ‘Botanist to Her Majesty’ (whose brother of Louis Ventenat (1765-1794) was a Catholic priest and chaplain naturalist who died on the d’Entrecasteaux expedition sent in search of the lost La Perouse expedition) wrote the accompanying plant descriptions referring to Australian plants as the ‘rarest plants growing on French soil’. A number of engravers were employed to produce colored stipple engravings of Redouté’s watercolors and this work appeared in twenty installments between April 1803 and November 1805 at a time when the work of British artists on the Australian flora remained hidden in folios and archives. It was 40 years from the naming of Botany Bay before substantial (unillustrated) botanical works describing the botanical collections of the Endeavour voyage were to appear. In spite of the Napoleonic wars that lasted from 1793 to 1815 it was over this period, with a few months respite, when Britain was at war with France that the Malmaison’s plant collections from the British colony of Nouvelle Hollande grew in splendour, Labillardière’s botany of Australia was published, and Redouté’s magnificent illustrations shone out across Europe.

Napoleon did not approve of the British employees and on being presented with an excessive bill by Howatson for transportation of shrubs to Malmaison, Napoleon had an opportunity to dispense with his services. The post of Superintendent of the Château de Malmaison gardens was given, in 1803, to the French botanist Charles-Francois Mirbel (1776-1854) who, when Josephine was absent, had full authority to manage the estate’s farming and botanical operations, even drawing up an inventory of the collections, but dismissed by Napoleon in 1806 for apparently encouraging Josephine to continue the drain on the estates finances. Howatson was replaced first by arborist-horticulturist Jean-Baptiste Louis le Lieur (1765-1814) and then in 1808 by a new Josephine appointment Aimé Bonpland (1773-1858) who remained in the position until her death in 1814.

Head Gardener Félix Delahaye

It was through de Mirbel that Félix Delahaye eventually obtained the position of Head Gardener at Malmaison, his original appointment in 1805 based on his experience with the Australian flora, the successful restoration of the gardens at Le Trianon, and also his work in Marie Antoinette’s old garden at Versailles. Delahaye was a prodigy of the Professor of Horticulture Thouin at the Jardin du Roi in Paris and the most fascinating of the many gardener-botanists sent on voyages of scientific discovery during the Enlightenment and who visited Australia.[17] He was gardener on the D’Entrecasteaux voyage sent out in search of the lost La Pérouse expedition in 1792. He had collected Australian plants during a 25-day anchorage at Tasmania’s Rechereche Bay (later named after one of the research vessels on the expedition) where he also set up a vegetable garden, later calling in at Adventure Bay. The garden at Malmaison was probably the most important collection of living Australian plants anywhere in Europe in this period and for several decades Delahaye was the only gardener in Europe who had actually seen the plants from New Holland growing in their natural habitat, and many of which he had collected himself. Although tensions developed between Delahaye and Josephine’s chief botanist Bonpland, Delahaye continued to work for Josephine until her death in 1814 after which he started his own business entered business (possibly in 1826 when Malmaison was sold).

End of an era

Josephine, at first regarded as socially gauche, adjusted to her elevated social position, living at Malmaison from the time of her divorce from Napoleonin 1810. In spite of her dalliances and lurid lifestyle, for 15 years she maintained the respect of the French public and her peers.

Josephine created a world of horticultural excitement, raising the rose once again to its aristocratic height, instigating some of the world’s most accomplished botanical art, and joining in the thrill of foreign exploration and Enlightenment science.

The end to this glamourous and romantic era came quickly. It took four days for her to die of pneumonia in 1814; Napoleon’s French Empire came to an end in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo; and Malmaison quickly fell into disrepair to be sold in 1826. Her rich horticultural legacy has, however, continued to this day.

Commentary & sustainability analysis

With the end of the French Empire in 1815 following the defeat of Napoleon by English and Prussian armies at Waterloo and the Treaty of Paris French influence and colonial power declined and the British aspiration to Empire gathered momentum. French claims to land in the antipodes included the Marion Dufresne claim to Van Diemen’s Land in 1772, Louis St Allouarn’s claim to the west coast of New Holland in the same year and the claims to the south coast of New Holland under the name Terre Napoleon made by Napoleon’s Baudin expedition of 1800-1803. Many French names disappeared from the charts and without subsequent settlement all these claims were to lapse.

Classical influence was a major part of French public life from the styling of its leaders as Emperor, Empress and Consul to the architecture and aesthetics. Empire, honour and military glory still gripped the male psyche.

Paradoxically, France at the time of Empress Josephine was caught in a frenzy of ‘anglomania’, the fashionable social elite seeking out English fabrics and teas – even assuming English manners like eating roast beef, wearing riding coats, enjoying horse-racing … and setting up gardens in the romantic English tradition, á l’anglaise, in preference to the formal rectilinear parterres so popular in France at the time.[10] In keeping with Roman and Greek tradition it was mostly the wives of powerful men who cared for these garden estates while the men were engaged in public affairs. In common with the rest of European society, France’s fashionable were also in the grip of ‘botanophilia’ and its love of natural history especially the plants. When the hopeful Revolution of 1789 turned into the Reign of Terror, botanophilia beamed out as a tantalizing other-world for the wealthy and influential – in a strange way it was an anodyne preoccupation for an age, a fusion of botany and horticulture: a coupling of science and aesthetics that could prevail for brief moments of respite in world away from grimy politics.

Josephine’s garden:

… may not only be regarded as housing the first international collection of roses – and thus starting their present popularity – but as being one of the first gardens in the new genre, where the design was explicitly to demonstrate the beauties of the plants themselves. This style has since become known as the Gardenesque … [16]

After Josephines death in 1814 Malmaison quickly fell into disrepair but the tradition of rose breeding and cultivation has continued to this day through people connected with Malmaison. Josephines favourites would now count as ‘heritage’ varieties, replaced by modern groups of cultivars like the teas, hybrid perpetuals, David Austin’s and so on.

Like her English contemporary Joseph Banks, Empress Josephine was a key link in the European network of social connections that included royalty, aristocracy, the wealthy, intellectuals and scientists, nurserymen, garden designers, social gardeners, explorer-gardeners, botanists and government officials. Because of her staus as first Empress of France she was able to set the fashionable trend of the day, not only in France but across Europe, and in so doing play a key role in delineating the future path of botany and horticulture by advancing the ideas and practice of: novelty plant introduction; botanical exploration and plant hunting; plant exchange and acclimatization; garden design and the use of professional landscapers; hothouse cultivation; botanical description; restoration of the rose as an aristocratic symbol; botanical illustration; and the elevation of science above politics.

Josephine freely shared her botanical spoils and is commemorated in the botanical names Amaryllis josephinae, (Josephine’s Lily, now named Brunsvigia josephinae), also a plant from western Australia described by Ventenat and called Josephinia imperatricis (now ), and the Chilean national flower Lapageria rosea, the Chilean Bell Flower, which recalls her maiden name, Marie-Josèphe-Rose de Tascher de La Pagerie (Napolean had invented the name Josephine from her Christian names since he did not like the very appropriate name by which she was generally known: Rose). The exquisite ‘Souvenir de Malmaison’ is a bourbon rose selected in 1843 by Lyon rose breeder Jean Béluze and it remains a favourite today.

Timeline

1798 – Josephine purchases Château de Malmaison while Napoleon leads the French army on a campaign in Egypt>

1800 -The European plant obsession ‘botanophilia’ reaches its height>

1800-1803 – Napoleon orders the Baudin & Hamelin expedition to the South Seas

1803 – Publication of Jardin de Malmaison an illustrated account of plants growing at Malmaison, by Pierre-Joseph Redouté

1803-1806 – Charles-Francois Mirbel appointed Superintendant Gardener at Malmaison>

1804 – Josephine crowned Empress of France by Napoleon in Notre Dame

1806-1808 – Jean-Baptiste Louis le Lieur replaces Mirbel

1804-1807 – Labillardière publishes Novae Hollandiae Plantarum Specimen

1804-1814 – Assemblage of horticultural collections at Malmaison, in particular the rose and Nouvelle Hollande collections>

1808-1814 – With the death of Ventenat, Bonpland takes over as Botanist & Conservator at Malmaison>

1811 – Shares cost of plant collection by Scotsman James Niven at the Cape of Good Hope with English nurserymen Lee & Kennedy

1814 – Napoleon exiled to Elba, escapes to Paris where he assembles army

1815 – Napolean defeated by a coalition of English and Prussian armies at Waterloo, banished to St Helena, the end of French Empire coming with the signing of the Treaty of Paris: his letter of surrender to the British throws him to their mercy ‘like Themistocles‘

1817-1824 – Publication of Les Roses by botanical illustrator Pierre-Joseph Redouté

Key points

- As a celebrated hostess and first Empress of France Josephine had a considerable influence over Europe’s fashionable social life, especially through the pride she took in the gardens and plant collection that she built up at the Château de Malmaison

- The rose garden at Malmaison was the first international collection and exhibition of roses and was a major stimulus to their present popularity and the Gardenesque style of garden planting. Malmaison was also the birthplace of the tea rose. Acclaimed botanical artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté was commissioned to produce a superb three-volume Les Roses (1817-1824) which was completed after Josephine’s death, the plant descriptions provided by the botanist Claude-Antoine Thory. She produced the first substantial history of the rose and encouraged the use of vernacular cultivar names in place of the usual Latin

- Josephine played a key role in delineating the future path of botany and horticulture by advancing the ideas and practice of: novelty plant introduction; botanical exploration and plant hunting; plant exchange and acclimatization; garden design and the use of professional landscapers; use of manageries in public gardens; hothouse cultivation; botanical description; restoration of the rose as an aristocratic symbol; botanical illustration; and the elevation of science above politics

- Josephine’s fascination with natural science and New Holland was shared by Napoleon who had made an unsuccessful application to join the La Pérouse expedition to the South Seas. After the Revolution in 1789 science was strongly encouraged and the number of professorships at the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle was increased to 12, three of which were botanists, and Napoleon continued to support this initiative

- Contact with England was close through Joseph Banks, Captain Cook’s publications on the South Seas, the Scottish landscapers Blaikie and Howatson, and the London nursery of Lee & Kennedy>

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

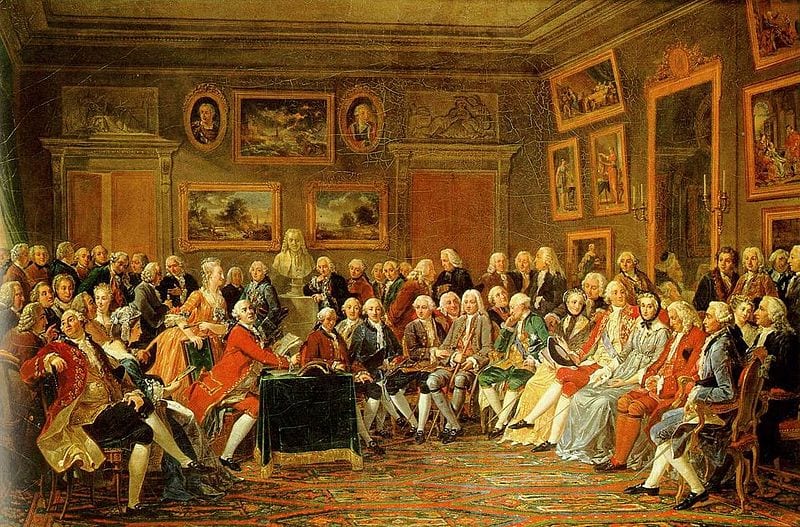

Eminent figures of the French Enlightenment as guests in the salon of Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin

This 1812 painting by Anicet Lemonnier (1743-1824) is now in the Chateaux de Malmaison

Back row, left to right: Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gresset, Pierre de Marivaux, Jean-François Marmontel, Joseph-Marie Vien, Antoine Léonard Thomas, Charles Marie de La Condamine, Guillaume Thomas François Raynal, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jean-Philippe Rameau, La Clairon, Charles-Jean-François Hénault, Étienne François, duc de Choiseul, a bust of Voltaire, Charles-Augustin de Ferriol d’Argental, Jean François de Saint-Lambert, Edmé Bouchardon, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, Anne Claude de Caylus, Fortunato Felice, François Quesnay, Denis Diderot, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune, Chrétien Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, Henri François d’Aguesseau, Alexis Clairaut

Front row, right to left: Montesquieu, Sophie d’Houdetot, Claude Joseph Vernet, Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle, Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin, Louis François, Prince of Conti, Duchesse d’Anville, Philippe Jules François Mancini, François-Joachim de Pierre de Bernis, Claude Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon, Alexis Piron, Charles Pinot Duclos, Claude-Adrien Helvétius, Charles-André van Loo, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, Lekain at the desk reading aloud, Jeanne Julie Éléonore de Lespinasse, Anne-Marie du Boccage, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, Françoise de Graffigny, Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Bernard de Jussieu, Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons