Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Photograph taken c. 1854 when Darwin was aged 45

Courtesy Wikipedia Commons

‘The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined the whole of my existence.’

Charles Darwin – Autobiography

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) – social recluse, meticulous scientist, and victim of Crohn’s disease – saw the world through new eyes. His monumental work On the Origin of Species, which he reluctantly published in 1859, presented a closely argued biological grand narrative, a unifying theory of the life sciences in which natural selection was invoked to explain the proliferation of the entire community of life from a common ancestor. It was a carefully crafted new and challenging scientific paradigm to be reconciled with the social, biological, and religious thought of his day.

To secure his achievement would require the moral support and temperaments of three other men who had all passed through the rigours of the southern ocean around Australia. They were men who helped carry their friend Darwin’s coffin to its resting place alongside Isaac Newton at the funeral in Westminster Abbey: Joseph Hooker (botanist Director of Kew Gardens, a biogeographer who fought hard in support of Darwin’s thesis), Thomas Huxley (brilliant scientist and confident public Darwinian advocate) and Alfred Wallace (shy and self-effacing naturalist, biogeographer, and co-originator of the theory of natural selection – but who was happy to defer to the senior man). Together they changed the world for all time.

HMS Beagle

From 1826 to 1830 an expedition to map the coasts of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego had been sent out from Britain. It comprised two vessels, HMS Beagle under Captain Pringle Stokes and HMS Adventure under the command of Captain Phillip Parker King. In tragic circumstances captaincy of the brigantine Beagle was handed over to the 23 year-old Robert Fitzroy (1805-1865) in 1828 when the deeply depressed Stokes, his ship in poor condition, scurvy rife, and in wretched weather, shot himself while the ship was wrestling with the bleak Strait of Magellan.

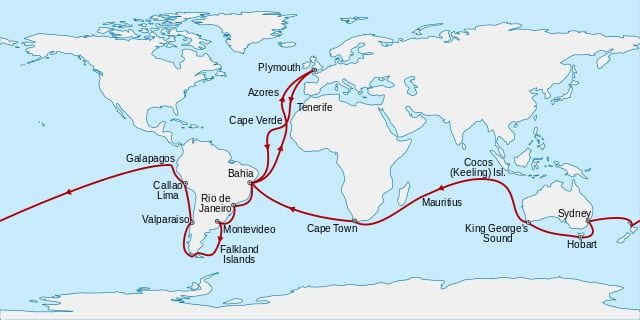

It was an unfortunate omen for Robert Fitzroy, now Commander of the second survey expedition of the Beagle[4] as he set out from Plymouth on the 27 December 1831 to complete King’s charting work along the coasts of Chile, Peru and Pacific islands while simultaneously making chronometric observations. On board was his self-funded companion-naturalist, the inexperienced young graduate Charles Darwin. This voyage was to be of momentous scientific significance and is briefly outlined here.

Early days

Darwin’s childhood was unremarkable. He was the grandson of Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) a prominent physician, philosopher, poet, and dilettante. As the son of a wealthy land owner Charles enjoyed ‘fishing, raiding birds’ nests, stealing fruit, collecting shells and hunting rats’[13] He never needed to earn a salary. As a boarder at the Anglican Shrewsbury School the young Darwin showed no aptitude for the traditional classical studies and his fooling around with chemicals had earned him the nickname ‘Gas’. He was tall and strong, sensitive and pleasant company but his school results were ordinary and he was frequently bored and much more interested in reading adventure stories and joining in the riding, hunting, and shooting jaunts on his other grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood’s, country estate. Wedgewood was a slave-trade abolitionist who founded the famous Wedgwood pottery and he wore a medallion saying Am I Not A Man And A Brother?

When Charles was only eight years old his mother, Susannah Wedgwood, died and his domineering father recommended that the young boy should follow his grandfather, father and elder brother into medicine by enrolling as a medical student at the prestigious Medical School of Edinburgh University.

Medical School at Edinburgh (1825-1827)

Darwin was bored by the lectures and appalled by the agony, suffering and bloodshed that was part of the surgery without anaesthetic at this time. He amused himself as a collector of butterflies, minerals, shells and other natural history curia, these interests probably instilled in him through the active and inquisitive mind of his other famous grandfather Erasmus Darwin – poet, botanist, physiologist, and naturalist. Erasmus was a believer in organic ‘evolution’ and, like his other grandfather Wedgwood, he was an abolitionist. Erasmus was an Enlightenment ‘freethinker’, someone who believed that opinions should be formed on the basis of logic, reason and empiricism – not authority, tradition, and dogma.

Another influence would have been the Reverend Gilbert White (1720 – 1793) who was renowned for his simple love of nature which he coupled with meticulous ecological observation. Gilbert’s The Illustrated Natural History of Selborne had proved one of the best-selling books in the English language (a recent reprint appeared in 2007). ‘Earthworms, though in appearance a small and despicable link in the chain of nature, yet, if lost, would make a lamentable chasm … ’.[17] It is perhaps no coincidence that Darwin’s final book was on the topic of earthworms.

Though Darwin neglected his medical studies at Edinburgh he nevertheless immersed himself in the fabulous collections of the Edinburgh Museum, studying in particular the lifestyles and anatomy of the marine invertebrates of the Firth of Forth, first in 1826 with his brother (also called Erasmus), and then in 1827 with the eminent Edinburgh zoologist Robert Grant, these times probably accounting for his later passion for barnacles. As a member of the student Plinian Society, a natural history society, there would also have been exposure to vigorous debates about ‘transformation’ and ‘transmutation’. These discussions strayed into ‘radical materialism’ the view that everything in the universe was comprised of matter or energy, including consciousness, a philosophical position bitterly opposed by the various spiritual ideas of the day as well as the philosophical position of ‘idealism’ which argued that reality, as we can know it, is an immaterial construct of the mind and that, in essence, all entities are composed of mind or spirit . . . here was the philosophical battleground: was the universe a great thought or a great machine? Were you a Platonist or an Aristotelian?

Young Charles’s interest in natural history was not viewed by his parents as a promising start in life for a gentleman. Botany and natural history were considered mostly lower-order pursuits, the hobbies of idle clergymen, genteel young women artists, plant-pressers, and artisans trying to better themselves. Botany at Edinburgh University at this time was not very stimulating, being essentially a preparation for life in the colonies where medicines were in short supply.[14]

Christ’s College Cambridge (1828-1831)

Darwin returned home from Edinburgh disenchanted with medicine and at his father’s suggestion unenthusiastically agreed to enroll in a Bachelor of Arts degree at Christ’s College Cambridge which promised a quiet future as an Anglican parson. Here he became friends with two clergymen professors, botany professor Reverend John Henslow,[15] a botanist-geologist, and Adam Sedgwick a geologist; he also befriended the botanist Robert Brown.

Still unsettled he preferred the outdoors to study and he spent a lot of time collecting beetles and enjoyed reading the natural theology arguments of of William Paley, and the other major supporter of intelligent design in nature, the astronomer John Herschel. His final results from College were not bad, tenth out of a total of 178 students.

In 1831 he joined the geology Professor Adam Sedgwick on a study tour of Snowdonia in North Wales but soon excused himself to join student friends at Barmouth on the nearby Welsh coast. It was shortly after this trip that he received a letter from John Henslow inviting him to join HMS Beagle on a circumnavigation of the world.

Voyage of HMS Beagle (1831-1836)

In 1831 with promising university results but mounting personal debt[10] he accepted his likely future as a country parson: at least it would allow him to indulge his interest in natural history. But before that the 22-year-old Charles was keen to see the world, although it needed grandfather Wedgwood to persuade his reluctant father to fund his passage.

Voyage of the Beagle

1831-1836

Courtesy Sémhur – Wikimedia Commons – Accessed 23 April 2018

Darwin especially admired the German explorer von Humboldt (1769-1859) whose Personal Narrative he would read again and again on the voyage, appreciating Humboldt’s theme of the harmony of nature’s diversity. He also took Milton’s Paradise Lost for on-board reading (perhaps he had heard of Banks’s reading list on the Endeavour, or even knew how Alexander always carried a copy of Aristotle‘s works of Homer while on his military campaigns), along with the Romantic poets. Throughout the voyage he constantly battled sea-sickness and shared a cabin with Philip Gidley King who would later make a major contribution to Australian navigational history. Collections from the voyage were in demand and they could go to whomever he wished, most being sent to Henslow at Cambridge but others retained for the Crown, passing first to the Admiralty and thence to the British Museum (Robert Brown had expressed interest).

Robert FitzRoy

Aristocratic Captain Robert Fitzroy at age 26 was already an accomplished seaman with a promising future. His father was a wealthy land owner and young Fitzroy had been educated at Harrow before graduating to the Royal Naval College at Portsmouth where he had excelled in maritime disciplines like cartography, hydrography, mathematics, and mechanics. Fitzroy was, however, sensitive to Stokes’s fate and, recognizing that he was himself prone to bouts of rage, suspicion and melancholy, he was looking for a steadying influence during the voyage. Henslow’s letter to Darwin had stated ‘. . . Captain F. wants a man (I understand) more as a companion than a mere collector & would not take anyone however good as a naturalist who was not . . . a gentleman.’

There were striking differences between the pair although it seems that as ‘gentlemen’, and in spite of Fitzroy’s hauteur, they got along together most of the time with only the occasional confrontation. Darwin was working mainly ashore on his geology and natural history collections while Fitzroy was busy with the main business of the voyage, the coastal hydrographic survey which was needed to draw up accurate nautical charts, part of which was painstaking recording of depths and accurate calculation of longitudes using precision chronometers (these had only become affordable after about 1800).

At first the naval preoccupation with rank and discipline irked Darwin but his letters home indicated that, over time, he began to take a pride in the ship and its achievements, the efficiency of the crew during crises and the necessity for onboard routines: he even asked to join the military action, armed with musket and cutlass pirate-style, when the ship was requested to quell a minor revolt in a fort at Montevideo.

On the ship were three Fuegians who had been brought back by Fitzroy from the previous voyage and he had personally paid for their Christian education. Dressed in European clothes and with European belongings along with a Fitzroy-sponsored English missionary it was assumed that they could be returned home to spread the principles of civilization and Christianity among their native people while also acting as translators and otherwise assisting with any further British contact in the region. Fitzroy had also paid for an artist, Augustus Earle (later replaced by Conrad Martens) and other items he particularly required, including 22 of the latest chronometers and a state-of-the-art lightning conductor.

His naturalist-companion Darwin was to be self-financing (that is, financed by his father) but fed and clothed by the navy. By this time the post of naturalist was regarded as an extravagance, these duties generally being allocated to the ship’s surgeons.

Later, back in England, Fitzroy was appointed to the House of Commons in 1841 and in 1843 Governor of New Zealand; then partly on the strength of new meteorological work in 1857 he was made Rear Admiral, Darwin inviting him to spend a couple of days in the country. Finding him embittered and exhausted Darwin wrote to his sister that Fitzroy had ‘the most consummate skill in looking at everything and everybody in a perverted manner’.[8]

His name is commemorated in the Patagonian conifer genus Fitzroya described by Joseph Hooker in 1851, although it had bern introduced to cultivation in Britain by nurseryman William Lobb in 1849.

The voyage

Social etiquette required that Darwin be called ‘sir’ by junior officers as he was a guest and social equal of the captain.[24] However it was not long before the amenable young man was known to the crew as ‘our flycatcher’, to the officers as ‘dear old philosopher’ (he was 22), and to FitzRoy as ‘Philos’.

After leaving Plymouth the ship touched in at Madeira, then called at Tenerife where a cholera epidemic prevented anyone going ashore.

Santiago, Cape Verde (Jan, 1832)

Darwin’s journal begins at the first major stopover which was Porto Praya on the island of St Jago (Santiago, Cape Verde islands) a volcanic island where the ship moored for 23 days. Here he was able to experience the tropical luxuriance of bananas, tamarinds, coconut trees and other palms – but it was the geology that would hold his attention.

Darwin was now familiar with the famous geologist Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830) which appeared in print the year before the Beagle set off. It was the most respected geology text of its day and a copy of volume one had been given to him by FitzRoy who knew the author, a creationist who believed in the immutability of species.

In the early 19th century geology was still extricating itself from the biblical story of creation in Genesis, the flood, Noah’s ark (Deluvianism), and the biblical timeframe that started in 4004 BCE. One school of thought, Neptunism, held that rocks were formed as strata settling out in water by sedimentation, the oldest being granite while newer layers contained fossils as a result of further flooding. In contrast Plutonism (Vulcanism), held that rocks were formed in fire, eroded by weathering and then re-formed and uplifted under heat and pressure, the whole process taking eons of time rather than the thousands of years assumed by biblical time-frames. It was only in the mid 19th century that geology began its escape from a literal interpretation of the bible and the story of the flood although there was general acceptance of three human phases of history based on the technological phases of stone, bronze and iron.

Scottish geologist and naturalist James Hutton had written in 1785 that ’no processes are to be employed that are not natural to the globe; no action to be admitted except those of which we know the principle’. He espoused Plutonism, and the radical view that the Earth was a super-organism. His dictum was the clarion call of ‘uniformitarianism’ whose later principle exponent was Charles Lyell. Lyells uniformitarian approach appealed to Darwin as he examined fossil shell deposits in the upper volcanic strata of the island and speculated on how the shell layer had been elevated so high by volcanic activity.

Brazil, Bahia (28 Feb.)

In South America the ship stayed at Fernando de Noronha for a day before putting into the Bay of All Saints in Bahia (Salvador), today’s eastern Argentina. It was one of the most memorable parts of the voyage for Darwin where for three weeks he was free to explore the delights of the Brazilian rainforest.

There was however a falling out between Fitzroy and Darwin fell out here as Darwin was appalled by the cruel treatment of black slaves while Fitzroy regarded this as a necessity of life. Darwin experienced FitzRoy’s temper when he grumbled about the inhumane treatment. FitzRoy’s temper was familiar to those aboard ship who passed it off as ‘hot coffee’. FitzRoy soon apologized to Darwin and the two were quickly on speaking terms again. Politically Darwin was from a liberal Whiggish background and with an abolitionist history while Fitzroy was a high Tory, a conservative traditionalist.

Rio de Janeiro (4 Apr.)

In Rio Darwin moved into a rented house at Botofogo from 26 April to 5 July spending three months absorbed in the bizarre tropical exuberance of plant and animal colour and form, collecting all the time while FitzRoy continued his charting.

Montevideo (26 Jul.)

There was then a short stay at Montevideo then on to Bahia Blanca where he was amazed by a find of fossilized bones. These bones threw up all sorts of questions about the history and age of the Earth and the different organisms that lived on it currently and in the past. Back aboard ship he explored his questions with Fitzroy whose literal interpretation of the Bible Darwin found exasperating.

In August the Governor of Montevideo asked Fitzroy to assist with a local uprising and Darwin eagerly joined the 52 sailors and marines armed with muskets and cutlasses to attack the fort occupied by the rebels but to his disappointment they surrendered peacefully.

Off Bahia Blanca (Aug.-Sept.)

On 19 August the first box of specimens was sent off to Henslow who had been instructed to hold them in store ready for Darwin’s return. Charting began off the Bahia Blanca coast which consisted of scrubby hills and pampas which Darwin explored on horseback with the gauchos (rugged half-caste Argentinian-Indian soldiers), eating ostrich eggs and roast armadillos. He learned with annoyance that the French government in its support for science had sponsored Alcide d’Orbigny to a six month expedition in the region (and six years overall) collecting specimens for the Paris Museum while Darwin himself was expected to pay privately for a similar brief privilege. But he was to be rewarded on 22 September when fossil bones of a giant megatherium were excavated from the Punta Alta cliffs.

Tierra del Fuego (Dec. 1832)

In Dec 1832 the vessel was in Tierra del Fuego where the sight of naked painted Fuegians set Darwin to musing about human origins. Two of their three Fuegians were, with some consternation, returned as ‘missionaries’ to their people, referred to by Darwin as ‘miserable degraded savages’. The aim was to establish a Patagonian mission led by English missionary Matthews and aided by the Anglicised Fuegians now named Jemmy Button,York Minster, and Fuegia Basket. Returning a year later in Apr. 1834 the mission had been abandoned with Matthews fearing for his life. York and Fuegia had moved to their ownpeople and Jemmy Button now near- naked again had married, declining an offer to return to England.[5]

Argentina Aug-Oct.1833

Trekking 500 km with gaucho cattlemen.

Into the Pacific (10 Jun. 1834)

Beagle sailed through the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific on 10 June with the west coast of South America looking unappealing as they put in to the main Chilean port of Valparaiso on 23 July.

Island Chiloé (Jan. 1835)

Off this island Darwin, spellbound, watched the eruption of Mt Osorno on the mainland discovering when, a few weeks later, they put into nearby Valdivia and Conceptión, a devastated landscape and being told that the eruption had been accompanied by the worst earthquake in a generation accompanied by a Pacific Tsunami. Then back to Valparaiso where Darwin in March climbed the western face of the Andes to about 4,500 m then downthe easternside of the Cordillera range. Having now read Lyells’s volume 2 he was musingon the effects of such a geographic barrier on the climate and composition of the vegetation, his thoughts challenged by the fossilized trees that he found in the rock at the tip of the Andean mountains and the possibility of totally different vegetation in the geological past. Before departing he made a last trek of about 700 km up the coast to the port of Copiapó where he was to meet up with the Beagle.

Falkland Islands

From Tierra del Fuego the ship sailed to a brief stop at the Falkland Islands before Darwin was left for three months at Maldonado travelling into the interior then packaging his specimens for dispatch back to England. Then putting in to El Carmen, the southernmost point of colonial presence in the pampas Darwin decided to trek in an armed party of six gauchos 1,000 km across the pampas to meet the ship at Montevideo. After journeying on the inhospitable coast and putting in to Valparaiso Darwin set back on a 6-week excursion on horseback studying the geology of the Cordilleras discovering shells and petrified pines in a region where earthquakes and eruptions were still evident.

The Beagle was a small vessel inadequate for some of its surveying tasks and while Darwin was trekking, Fitzroy had purchased a larger American vessel but without contacting the Admiralty. Eventually news came through that the purchased could not be supported throwing Fitzroy into a rage and despair, feeling he was losing control and telling his officers that ‘there was insanity in the family’.[6] Eventually the ship was sold at a slight profit and Fitzroy calmed down the ship proceeding to the islands off the coast of Chile before putting in to Valdivia where Darwin experienced several earthquakes. Darwin left the Andes crossing the Cordillera by a high and dangerous route arriving in Mendoza on the other side feeling in great physical condition, then proceeding 700 km to Copiapo to meet up with Fitzroy now in good spirits having received a promotion to captain.

Moving on to Peru Darwin made a brief visit to Lima before they headed to the place Darwin had been looking forward to, the Galapagos Islands.

Galapagos Islands

Here the ship sailed from island to island Darwin drinking in the exciting volcanic geological formations and observing how the animals were adapted to their local conditions. His most profitable time was spent on James Island (San Salvador) where he spent a week with four others admiring the giant tortoises, huge iguanas, and the range of finches whose beaks provided an interesting comparison with those on other islands, their form being a clear adaptation to their food source. These finches were to later feature in his argument for ‘natural selection’ in the Origin of Species although their significance was not appreciated at the time.

It was in the Galapagos that he first seriously entertained the idea of variation deriving from common ancestral forms; that is the mechanism of speciation. He was so excited by these ideas that he wrote to his sister saying that he was having difficulty in sleeping.

Return journey

The main official work of the voyage was now complete and the men relaxed a little with only a few chronometric measurements left. From this point Darwin’s journal indicates travel fatigue and a desire to be back in England his dismissive remarks being even more marked than usual. The ship putting in to Tahiti where Darwin was disappointed by the women (now no doubt Europeanised in various ways), then on to the Bay of Islands in New Zealand where the Maoris did not make them welcome although Darwin especially noticed the quality of the colonial gardens. Missionaries had been in strong evidence in both stops and appeared to be giving some assistance.

Sydney & Hobart

Arriving in Sydney on 12 January 1836 Darwin felt proud of the rapid English progress and prosperity and he enjoyed pleasant strolls in the Botanic Gardens and Government Domain. There were now impressive large buildings and many others under construction although people were complaining about the cost of both houses and rent. Carriages with liveried servants were evident. He made several critical observations: in a city of about 23,000 people he noted that there was an idle class living off the labour of the convicts; there was tension between emancipists and free settlers; an absence of literature and a preoccupation with acquiring wealth; luxuries were plentiful and food cheaper than in England; the number of Aboriginals was rapidly declining and they appeared uncomfortable in their own land; animals like the emu and kangaroo were becoming scarce from the use of hunting dogs. While in the colony for about six weeks he rode over the Great Divide to Bathurst impressed with the macadamized road surface, especially through to Parramatta, and he enjoyed catching the sight of a platypus.[11] It was clear to him that the lack of water would hamper future development.

Sailing on to Hobart the Aboriginals seemed in even worse condition and he did not really like Hobart town although the countryside appealed and he climbed to the top of Mount Wellington, admiring the tree ferns and noble eucalypts.

Then on to King George Sound in the west of the continent, a settlement of 30-40 small whitewashed cottages, where he experienced a Corroboree but all-in-all was happy to leave on March 14th. Darwin was tired of journeying and pleased to be setting off home: he had not seen the more biologically stimulating landscapes of the continent and Australia was not given a good report. Most of the places he visited he was pleased to leave behind but none more so than King George Sound and Australia ‘if he thinks, like me, he will never wish to walk again in so uninviting a country’. On leaving King George’s Sound Darwin wrote in his journal: ‘Farewell Australia, you are a rising infant and doubtless some day will reign a great princess in the South, but you are too great and ambitious for affection, not great enough for respect; I leave your shores without sorrow or regret.’ This remark should be taken in the light of his other journal comments: he was ‘glad to leave’ New Zealand, and later found the Cape Town area ‘the most uninteresting country he’d seen’.

In spite of this disdain some of his most important biological insights were made among the islands and continents of the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Cocos Keeling

The ship moved on to the Cocos Islands(Cocos Keeling) where Darwin theorized about the formation of coral reefs.

Cape of South Africa

Calling in at the Cape Fitzroy and Darwin visited Darwin’s student hero and FitzRoy’s acquaintance astronomer John Herschel. Between 1834 and 1838 he was cataloguing the stars and nebulae of the southern skies. Herschel who in England was highly respected and in much demand was happy to get away from his hectic life, regarded his time in Africa as probably the happiest time in his life as, taking a break from his astronomy, he and his wife Margaret shared the work of producing 131 delightful botanical illustrations of the Cape flora using a camera lucida to ensure the accuracy of the floral outline and dimensions., a compilation of the 112 best being published in 1996 as Flora Herscheliana.

Then on to Mauritius, St Helena, Ascension and, to Darwin’s disappointment, before returning to England Fitzroy steered once more to South America.

Finally the ship completed its voyage on 2 October 1836. Of the nearly five years away Darwin had spent three years and three months on land. Though travel-weary and keen to get back to England Darwin was consistent in his disdain. On his return he wrote ‘To my surprise and shame, I confess the first sight of the shores of England inspired me with no warmer feelings than if it had been a miserable Portuguese settlement . . . ’ Was he already thinking of further travel? It seems unlikely as he later admitted to his family ‘I loathe, I abhor the sea and all the ships which are on it’.[18]

Back in England

For the first two years back in England bachelor Darwin worked hard and joined the social whirl, befriending geologist Lyell (who had placed geology within a timeframe of millions of years contrary to the prevailing accepted view of Irish Bishop Ussher who had dated the creation to the night preceding Sunday, 23 October 4004 BCE according to the proleptic Julian calendar) and comparative anatomist Richard Owen (who would later attack Darwins new theory) and botanist Director of Kew gardens Joseph Hooker (one of his most outspoken advocates). However this brief period of London parties and the entertaining of international scientists didn’t suit the retiring Darwin, who was totally unlike his highly sociable predecessor Joseph Banks. Darwin became ill and in 1839 he moved with his new wife to the country town of Downe in Kent. Here Darwin assembled his work and ideas at the family home called Down House where he constructed a perimeter gravel path which he called the ‘sandwalk’ or his ‘thinking path’, one side flanked by an oak wood and the other with picturesque views across the adjacent valley. He took a daily walk of several circuits, not only for exercise but also to mull over his ideas. At one place he had a number of stones on the side of the path, kicking one to the other side with each circuit so that he instantly knew the number of circuits he had completed without having to interrupt his thoughts by counting.

About this time he also met his former explorer hero and inspiration von Humboldt, a major reason why he set sail in the Beagle but, as on so many other occasions in his life, could not be complimentary, describing him as ‘only a paunchy little German’.[22]

Acquaintances were renewed with botanist John Henslow, who had agreed to process his botanical specimens collected on the voyage, and Robert Brown who he held in great respect, and he struck up a correspondence with Asa Gray in America. Darwin would later dedicate The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species (1877) to this Harvard Professor of Botany who was arguably the most important American botanist of the 19th century.

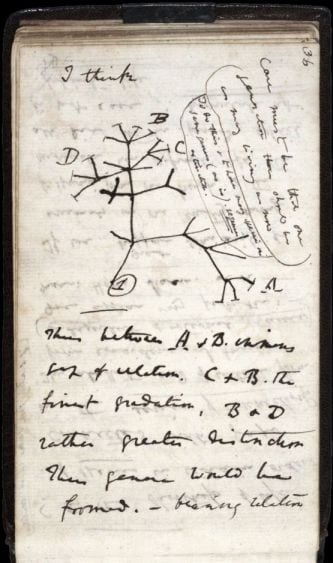

With inherited wealth Darwin’s time was his own and he set about writing up and publishing his work. He was now totally convinced that evolution was a fact but still uncertain of the precise mechanism by which it occurred. By July 1837 he was sketching evolutionary trees showing branching descent and describing as ‘absurd‘ the notion that some organisms were ‘higher‘ than others. In 1838 he read Thomas Malthus’s On population. The ‘struggle for subsistence’ that Malthus noted corroborated what Darwin saw everywhere in nature and it was to be the stimulus for his theory of natural selection. He spent much of his time in markets and with farmers and pigeon-fanciers examining the human process of ‘artificial’ selection of birds, dogs, cattle, sheep, and horses as well as plants.

Darwin had married his cousin and childhood friend Emma Wedgwood, Emma giving birth to 10 children (the large numbers were not unusual for this time) of which four sons survived their father. Darwin’s 1839 publication of the voyage of the Beagle (a third volume of a series of three) proved more popular than that of Fitzroy, his version being published separately in 1845 and subsequently translated into many languages.

For Darwin, however, everything was a strain. He stopped travelling in 1842 and after 1859 avoided appearing in public observing much later, in 1871, that he had never spent a day without feeling ill ‘always suffering from gastro-intestinal problems accompanied by vomiting, somnolence, and heart trouble. The doctors were unable to ascribe this incurable illness to any organic cause’[7] His palpitations, ‘accursed stomach’, periods of ‘inexpressible gloom’, sleeplessness, head noises, trembling, and vomiting (a terrible reminder of the endless seasickness when on the Beagle) have been the subject of much debate, being attributed variously to guilt, depression, psychoneurosis and Chagas’s disease caught from the great black bug of the Argentinian pampas. He had desperately sought a diagnosis from 18 doctors but without success. Certainly the very real symptoms allowed him to avoid the various social and academic chores that would have diverted him from his own interests.

In 2014 two of Darwin’s 130-year-old beard hairs (stored by his daughter in an envelope away from sunlight in her writing box and donated by his great, great grandson for analysis) were subjected to a genetic screening that revealed he suffered from the hereditary Crohn’s Disease: a total of twenty-one markers for Crohn’s disease were found, five of them being diagnostic, including the major marker on chromosome 16. Crohn’s Disease had not been discovered in Darwin’s day and it is ironic that his sickly children (only four of the ten survived him) were, in effect, victims of natural selection.

In 1842 he penned a 35-page resume of his theory and by 1844 this had expanded to 230 pages. Ten years would pass after the return of the Beagle before he finally confessed to his friend Joseph Hooker at Kew that he was now working on the theory of evolution. He did not find it a pleasurable task as it conflicted with the religious views of the time held dear by his wife and many of his friends and associates. His concerns may have contributed to his various ailments and the long procrastination over publication.

In 1856 after 20 years work he began assembling his definitive theory and had completed 10 chapters when, in 1858, he was asked to comment on a manuscript sent to him by geologist Alfred Russell Wallace who had, in a fever of Malaria while on the island of Ternate in the Moluccas, come to the same conclusions as himself. It was a dilemma solved by Lyell and Hooker when the two theses were jointly presented at the Linnean Society on 1 July 1858, while the following year Darwin released On the Origin of Species which was an immediate success, the stock of 1,250 copies sold out immediately and quickly followed by another couple of printings.

Release of On the Origin . . . prompted the inevitable rancorous debate. Darwin described the view that species were not immutable as ‘like confessing a murder’ and excused himself from the public fracas on the grounds of ill health, especially one critical meeting of the British Association at the Oxford University Museum in 1860 where the new theory was subjected to open critical public debate, his fear of being labelled ‘The Devil’s Chaplin’ being vindicated. In Darwin’s absence the tough debater and defender of evolution Thomas Huxley clashed acrimoniously with the special creation advocate Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, Huxley carrying the day and earning himself the sobriquet ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’.

The impact of Darwinism – from ladder to tree

Charles Darwin’s Tree – 1837

His first sketch of an evolutionary tree – from his First Notebook on the Transmutation of Species

The notes say ‘I think … case must be that one generation should have as many living as now. To do this and to have as many species in same genus (as is) requires extinction. Thus between A+B the immense gap of relation. C+B the finest gradation. B+D rather greater distinction. Thus genera would be formed. Bearing relation (next page) to ancient types with several extinct forms‘

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Scewing – Accessed 23 April 2018

Darwin’s theory deeply insulted the sensibilities of his day, undermining many widely- and tenaciously-held beliefs.

First, there was the conviction that species were immutable, each uniquely placed on Earth by God and unchanging over time. The idea that new species could gradually arise over many generations was considered not only absurd but blasphemous. Scientifically, Darwin had replaced unchanging and discrete species with organic change and a physical connection in time that embraced the entire community of life. He had brought history and time into biology.

Second, and even more insulting to the dignity of humans (the pinnacle of God’s Creation) was the implication that humanity had emerged in a decidedly undignified way from ape-like ancestors. For this suggestion Darwin was mercilessly lampooned in the daily press by cartoonists who depicted him as a monkey.

Third, Darwin’s theory placed in question the imagery of one of Aristotle’s most widely-accepted ideas about the structure of the natural world, the scala naturae or Great Chain of Being as adapted by Christianity. This was a popular understanding of the whole of the Creation on Earth arranged hierarchically from higher to lower like the rungs of a ladder, and surmounted by its crowning glory, the human being eclipsed only by God. While contemplating the origins of living organisms Darwin had drawn in his notebooks, not a top-to-bottom ladder, but a tree-like structure where humans, for all their magnificence, were not at the top of the ladder but at the tip of just one branch. Though evolutionary paths were constrained by what had gone on before, the selective interaction between organisms and their environments had many solutions. Darwin had replaced the popular image of the living world as a hierarchical ladder with the image of a tree.

Fourth, and most disturbing of all, Darwin’s theory undermined a universal human belief that dated back into prehistory, the conviction that there was a supernatural grand design to the living world, the universe, and everything in it: On the Origin of Species had removed the necessity for God as an integral part of our understanding of nature, and this changed human perception of the world forever.

From a Darwinian perspective the community of life had arisen over many generations in a perfectly intelligible mechanical sequence of events according to the laws of physics and natural selection – even if the whole process took an extremely long time and we may never know every step in precise detail. For natural scientists the theory of evolution neatly combined into a unifying and coherent theory anomalous information that had been steadily accumulating in biogeography, geology (notably its fossils, geological strata, and much-extended time-frame), embryology, and studies of artificial selection in the domestication of animals and plants. It placed humans within a branching evolutionary tree that dated back many thousands of years, and a geological time frame of eons that, less than 200 years ago from today, most Europeans, including the brilliant mathematical physicist and engineer physicist Lord Kelvin, believed was no greater than about 6,000 years, and insufficient time for evolution to have occurred. Under the influence of Thomas Huxley natural theology was now challenged by what became known as ‘naturalism’, a form of Huxley’s agnosticism, which asserted that only the natural world and natural laws exist: that there is no credible evidence for spiritual or supernatural forces.

No longer able to resist the explanatory power of Darwin’s thesis the various Christian churches eventually moved away from a literal interpretation of the Bible. Much of the Bible’s historical content now became interpreted as metaphor, allegory, and parable. To this day many people still question the theory of evolution, claiming that it is mistaken, preferring to believe the Christian biblical story of Adam and Eve and the Creation as described in Genesis. Others argue that there is no conflict between the two accounts. The power of Darwin’s idea has continued to attract intellectuals wishing to apply it to other aspects of human life, especially the socio-cultural.

Darwin had in 1860 sent the internationally famous Melbourne botanist Ferdinand Mueller a personal copy of On the Origin of Species . . . but Mueller died in 1896 still believing in the immutability of species.

Darwin was a Platonist who in later life became an Aristotelian (see Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle): he increased our existing wonder of the natural world through the staggering simplicity of his thesis. Fifty years before Einstein devised the mass-energy equivalence equation e = mc2, Darwin had explained the history of all life on Earth through the idea of replication with variation and selection.

Timeline

[23]

1809 – (2 Feb) Charles Darwin is born at The Mount, Shrewsbury, the fifth child of Robert Waring Darwin, physician, and Susannah Wedgwood

1817 – Darwin’s mother dies, his three older sisters assuming her role. Darwin starts at Unitarian day school

1818-1825 – Darwin attends Shrewsbury School as a boarder but hates it, dewscribing the school as ‘narrow and classical’

1825 – Removed from school, regarded as unsuccessful he spends the summer accompanying his father on his doctor’s rounds before being sent in the autumn to Edinburgh University with his brother Erasmus to study medicine

1825-1827 – Attends medical school at Edinburgh University but becomes disillusioned and spends his time mostly on natural history interests

1826-1827 – Studies marine invertrebrates in the Firth of Forth with brother Erasmus and then scientist Robert Grant; a member of the University Plinian Society which debated controversial issues in biology

1826-1830 – HMS Beagle and HMS Adventure sent by British Admiralty to map the coasts of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego; suicide of Captain Stokes and replacement by Robert Fitzroy

1826 – Joins the Plinian Society in Edinburgh and meets his most influential Edinburgh mentor Robert Grant

1827 – Finding medicine abhorrent he leaves Edinburgh without taking a degree, his father, fearing Charles will become idle, insists that he take up clerical studies in Cambridge

1828 – After re-learning Greek, Darwin enters Christ’s College, Cambridge

1830 – Charles Lyell publishes Principles of Geology

1828-1831 – Attends Christ’s College Cambridge to complete the Bachelor of Arts needed to become an Anglican minister but cultivates his relationship with botanist John Henslow and geologist-botanist Adam Sedgwick, joining Sedgwick on a study tour of Snowdonia in North Wales in 1831; received letter from John Henslow inviting him to join the HMS Beagle circumnavigation

1831-1836 – Voyage of HMS Beagle – Madeira, Tenerife, Santiago, Bahia, Rio, Montevideo, Tierra del Fuego, Chiloe, Falklands, Galapagos, Hobart, Sydney, Cocos Keeling, Cape of Good Hope

1836 – 12 January docks in Sydney and explores the Botanic Gardens and Domain, then on to Hobart, arriving in the West in March

1831 – Sits BA exam and is amazing to be ranked 10th out of 178 candidates

1831 – (27th Dec.) finally sets sail on HMS Beagle

1836 – (October) – HMS Beagle returns to England, docking at Falmouth in October. Darwin finds that Henslow has already published some of his letters in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society and Sedgwick had read extracts to the Geological Society of London

1836 – Between 1826 and 1836 Darwin publishes five volumes of his Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle establishing his reputation as a scientist and author

1836 – Meets the geologist Lyell for the first time

1837 – Sketches preliminary evolutionary trees in his notebooks

1837 – (4th Jan.) Reads his first scientific paper Observations…on the coast of Chile at the Geological Society in London

1837 – Moves from Cambridge to 36 Great Marlborough Street, London

1838 – Elected to the Athenaeum

1838 – Reads and is impressed by Thomas Malthus’s On Population; spends time studying the artificial selection of palnts, birds, dogs, horses and birds

1839 – Moves to Down House in Downe, Kent; publication of Voyage of the Beagle with Fitzroy (published separately in 1845)

1839 – Joseph Dalton Hooker sails to the Antarctic in HMS Erebus

1839 – HMS Beagle journal is published under the title Journals and Remarks volume three of Darwin’s Narrative …

1839 – Marries Emma Wedgwood, his first cousin: first child, William Erasmus, born on Dec. 27

1839 – Elected to the Royal Society

1840 – Elected to the Council of the Royal Geographical Society

1841 – Fitzroy appointed to House of Commons

1841 – Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs published

1842 – Writes a 35 page sketch of his evolutionary theory

1842 – Writes a 35-page synopsis of his theory which has extended to 230 pages by 1844

1842 – Darwin and his young family move to Down House

1843-4 – Writes Volcanic Islands

1843 – Fitzroy appointed Governor of New Zealand

1844 – Pleased by Joseph Hooker’s response to early drafts of his evolutionary theory, Darwin completes a 231 page manuscript while, in the same year, Robert Chambers publishes Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a popularisation of evolution theory that is generally rejected

1846 – Darwin completes his last book describing the voyages of HMS Beagle, Geological Observations on South America

1846 – Huxley appointed Assistant Surgeon on HMS Rattlesnake

1847 – Huxley meets Henrietta, the girl of his dreams, in Sydney

1849 – Darwin no longer attends Church but goes for walks instead

1850 – Huxley appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society

1851 – The first of two volumes on stalked barnacles is published, revising this subclass of both fossil and living Cirripedia

1853 – The Royal Society awards Darwin the Royal Medal for his work on barnacles

1854 – Elected to the Royal Society Philosophical Club and to the Linnean Society

1855 – Performs experiments to show that seeds, plants and animals can reach oceanic islands, where they might produce new species in geographic isolation

1856 – (April) Invites Huxley and other naturalists to a weekend party to discuss his ideas on the origin of species and then begins writing encouraged by Lyell and the concern that others might publish first

1856 – Darwin begins final work on his Origin, completing 10 chapters

1857 – Fitzroy appointed Rear Admiral of the Fleet

1858 – Darwin is asked to comment on Alfred Wallace’s views on evolution, so similar to his own; on 1 July the two views are jointly presented to the Linnean Society

1858 – (1st July) Wallace sends Darwin his own similar interpretation of evolution. Advised by Hooker and Lyell extracts from Darwin’s work and a paper by Wallace are presented at the Linnean Society, later published as On the tendency of species to form varieties in the Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society (Zoology). Wallace is informed after the event but is content

1859 – Darwin writes the book without references and therefore appropriate for a general reading public and titled On the Origin of Species … The 1859 print run of 1250 copies is oversubscribed so he begins corrections for a second edition. Huxley proveds a forthright defender of Darwin’s thesis

1859 – Publishes On the Origin of Species with 1,250 sold immediately followed rapidly by two more print runs

1860 – Public debate on evolution organised by the British Association at the Oxford University Museum. Thomas Huxley clashes with Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, Darwin does not attend

1864 – Awarded the Copley medal, a scientific award given by the Royal Society for ‘outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science’ and alternating between the physical and the biological sciences. On the Origin of Species is omitted from the award

1865 – FitzRoy commits suicide by cutting his throat with a razor

1866 – Darwinism dominates the views of the British Association as his supporters Hooker and Huxley assume consecutive presidency

1868 – The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication is published

1869 – Huxley coins the word ‘agnostic’

1871 – The Descent of Man is published, and the … Origin … is extensively re-written to answer arguments by Mivart – the sixth and last edition uses the word ‘evolution’ for the first time

1872 – Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals completes his evolutionary writings

1877 – Cambridge bestows Darwin with an honorary doctorate of law

1877 – The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species dedicated to Harvard Professor of Botany Asa Gray

1880 – The Power of Movement in Plants published 6 November 1880 by John Murray, soon selling 1500 copies

1881 – The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms assisted by his son Francis

1882 – (10th April) After a heart attack followed by seizures, Charles Darwin dies in great suffering at Down House. He is later buried in Westminster Abbey

2014 – Genetic analysis of Darwin’s beard hairs reveal that he suffered from Crohn’s disease

Commentary & sustainability analysis

‘Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways; but they were mere schoolboys to old Aristotle’

The Life & Letters of Charles Darwin

Darwin’s funeral at Westminster Abbey was attended by a congregation of about 2,000 people. Starting out life training for the Christian ministry he had long struggled with his religious beliefs moving from literalist to natural theologist to a Huxleyan agnostic.[21] While on the Beagle he was anticipating a future as an Anglican parson and he had made a special study of missionary work in the countries visited in the latter part of the voyage. As his ideas changed it was clear that in later life he had rejected God. From 1849 he would go for walks on Sundays while his family attended church and he was not concerned by the possibility of eternal damnation, his last words being ‘I am not in the least afraid to die’.[12] Though he would have preferred a small funeral service at his local church his wife Emma agreed to a state funeral in London although she did not attend.

Though his intellect cut through many of the scientific prejudices of his day his general views about life reflected his times: the secondary place of women in society, the superiority of European civilisation (although he abhored slavery and the mistreatment of indigenous peoples). He never linked himself to the ideas of eugenics or social Darwinism.

As men of means Banks and Darwin were self-financed and free to pursue their own interests without the stress of obtaining a regular income. Gentleman Joseph Banks took an entourage of 11 servants and assistants on Cook’s Endeavour and a couple of greyhounds while gentleman Charles Darwin was, before the voyage on the Beagle accompanied by a single manservant, Joseph Parslow, who for over thirty years worked variously as his butler, head servant, companion, scientific assistant, and nurse. Parslow was replaced by Syms Covington,[25] his manservant on the Beagle, and for a while after.

Though Darwin himself was inoffensive his theory was an affront to the beliefs of his day. It seems likely that his lifelong ailments, and long procrastination in publishing his theory, were in part a manifestation of his dread of the inevitable reaction that would greet his life’s work. He was right. The papers dubbed him ‘The Devil’s Disciple’ and pointed out the arrogance of his challenge to natural theology’s intelligent design by a divine creator. Cartoonists had a field day lampooning the degrading implication that humans were related to monkeys.

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection provided a coherent explanation and mechanism for the origin and diversity of organic life – for descent with modification from a common ancestor. This challenged the prevailing view that each species had been created uniquely and placed on Earth by God. It was a theory suggesting that humans arose in an undignified way from apes and it attacked the classical assumption of a Great Chain of Being arranged from high to low in which humans were the moral pinnacle for which the whole of Creation existed. Darwin perceived humans as one branch among many on an evolutionary tree. Humans, according to Darwin, had not arisen as a consequence of either their own, or God’s, willing but as a result of a selection process that existed in nature itself – ‘natural selection’. There was no longer an indisputable need for special creation, a supreme designer, or divine plan and this would change human perception of the world forever.

The theory of evolution, descent with modification under natural selection, was in many ways the culmination of Enlightenment science: it created a new grand narrative because it placed humans within nature rather than separate from it and challenged the idea of human moral superiority within the universe. Like Aristotle, Darwin was a great theoretician who spent many laborious hours engaged in the practical work of dissecting, observing and analysing plants and animals directly.

By about 1870 his new grand narrative, the reality of evolution, was broadly known and appreciated but Darwin’s claim for natural selection as its driving force remained controversial until the modern evolutionary synthesis of the period 1930-1950. The significance of what he had done was hardly appreciated.

In 1860 William Hooker (1785-1865), first Director of Kew Gardens (following Joseph Banks) from 1841 to 1865, published with George Arnott a new seventh edition of The British Flora in which it was stated: ‘Many species … were simultaneously called into existence on the third day of creation each distinct from the other and destined to remain so.’. The 7th edition of 1855 had stated ‘A species … is formed by our Maker, as essentially distinct from all other species as man is from the brute creation; it can neither for convenience be united with others, nor be split into several; but the difficulty is to ascertain what is such a primitive or natural species; and it is here so great a difference of opinion exists‘. We can see a generational shift in thinking between William Hooker and his brilliant botanical son Joseph, Kew’s heir-in-waiting to the Directorship (he was eventually Director from 1865 to 1885) who defended and supported Charles Darwin and his world-changing new theory of natural selection published one year previously in 1859. Australia’s greatest ever botanist, Ferdinand Mueller (1825-1896) died near the start of the 20th century believing in the immutability of species and the falsity of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Philosopher Dan Dennett

The significance and impact of Charles Darwin’s ideas.

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

Voyage of the Beagle – 1831-1836

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons