Cook’s voyages

Official portrait of Captain James Cook in 1775

Oil on canvas portrait by Nathaniel Dance

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Accessed 10 March – 2021

Introduction – Cook voyage1

Dampier’s two voyages in 1686-1691 and 1699-1701 had left many unanswered questions about New Holland which remained an enigmatic land mass. How far was it from Staten Landt (New Zealand); was Van Diemen’s Land an island or a promontory; was New Guinea part of the mainland; was the east coast as inhospitable as the other coasts?

With the mapping of the east coast of New Holland still to be completed a further voyage was planned by the British Admiralty, ostensibly for purely scientific purposes, and it was placed under the charge of expert navigator Lieutenant James Cook in HMS Endeavour.

Cook’s voyage of scientific exploration in HMS Endeavour was to be a momentous event for both the continent of Australia and its botany: it was the first of three great voyages to the Pacific between 1768 and 1780, the last ending with Cook’s death in Hawai. Cooks voyages, more than any others, captured the imagination of Europeans, with Cook and Banks lionized as heroic adventurers. As ship’s botanist on the first voyage, the socially established, charismatic, and internationally influential Banks (who would become president of the Royal Society for over 40 years) ensured that plants would be high on the European scientific and political agenda for many years.

The first voyage in HMS Endeavour (1768-1771)

The crew for this voyage totaled 94 people and reflected the increasing Enlightenment emphasis on natural history (see page) as it entailed a largely ‘professional’ scientific party that included: the Astronomer Royal, Charles Green; two artists, an illustrator Sydney Parkinson to record the colours and shapes of the biological specimens before they were preserved for the journey home (who was to die after contracting dysentery in Batavia) and landscape artist Alexander Buchan (an epileptic who died of a seizure in Tahiti); and the self-financed naturalist Joseph Banks.

Banks & Solander

The 25-year-old wealthy Banks brought his own entourage on the expedition, his company including an assistant naturalist, the Swedish botanist Daniel Solander, a Fellow of the Royal Society and a respected pupil of Linnaeus (and therefore familiar with the latest methods of plant description and classification) who Banks had met while Solander was cataloguing specimens at the British Museum. There were also four domestic servants (two were negroes), a secretary botanist the Finnish Herman Spöring (who died at sea), his two pet greyhounds, and a mound of baggage and the latest scientific equipment: he also had his own cabin.

Young, dashing and self-assured, Banks was ten years junior to the portly Solander and was prepared to swap the security of his wealth for the adventure of the high seas. When asked if he would do a Grand Tour he is said to have replied:

‘Every block-head does that. My Grand Tour shall be one around the world.’[1]

Dr Daniel Solander, Sir Joseph Banks, Captain James Cook, Dr John Hawkesworth and Lord Sandwich

Painted by John Hamilton Mortimer, 1771.

Cook centre, Banks seated with Solander behind

National Library of Australia (NLA) digital collections: http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an7351768 In publishing this image on their website, the NLA request that users cite the artist, title, the National Library of Australia as the custodian of the original work and their catalogue reference number

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Accessed – 10 March 2021

Cook & Banks

East Yorkshireman James Cook (1728-1779) was from humble stock working as a grocer boy, his father a farm labourer. Joining the navy at age 18 he had served on merchant ships and seen action against the French in the Seven Years War (1756-1763). He had won praise from the Admiralty for his charting and navigational skills while working in the north Atlantic on the Canadian Labrador and Newfoundland coasts and the St Lawrence River near Quebec which was a French possession. As a sea captain he was a strong disciplinarian who took good care of his crews soon gaining their respect, insisting on food that would counter the marine scourge of scurvy. HMS Endeavour was a sturdy barque originally built to carry coal.

The brief

Cook’s instructions from the Admiralty were to observe the transit of Venus in Tahiti on 3 June 1769. Venus crosses the face of the Sun about twice each century and measuring the duration of the transit would yield an estimate of the distance between the Sun and Earth also the Earth and Venus which would scale the solar system and assist with navigation. With this task completed he was to open sealed instructions which would direct him to continue west in search of Terra Australis Incognita, the Great South Land, by navigating the unexplored seas between New Zealand and South America. He was to take possession of any new lands that might be of benefit to Britain ‘in the name of the king’.

‘with the consent of the natives take possession of convenient situations in the name of the King … or if you find the land uninhabited, take possession for His Majesty’.

Banks’s background contrasted with that of Cook. Cook was raised on a farm in Yorkshire, starting out life as a grocer’s lad, while Banks (see Banks) was the son of a wealthy country gentleman on a large estate. He had taken up natural history when he became fascinated by the wildflowers growing around his elite school of Eton College (see Banks). By an unusual coincidence, while Cook was honing his navigational skills charting the coast of Newfoundland Banks was, at the same time, collecting specimens of the island’s natural history: it seems truly remarkable that, with the ship so commandeered by Banks’s presence, staff and belongings, that this unlikely pair got along so well.

Botanists, including Linnaeus himself, had experimented and written about plant and seed preservation and storage on long sea voyages. But much was still to be learned on this voyage in the constant battle against damp, disease, insects and mould – practical experience that Banks would later pass on to the many collectors he would send out to New Holland.

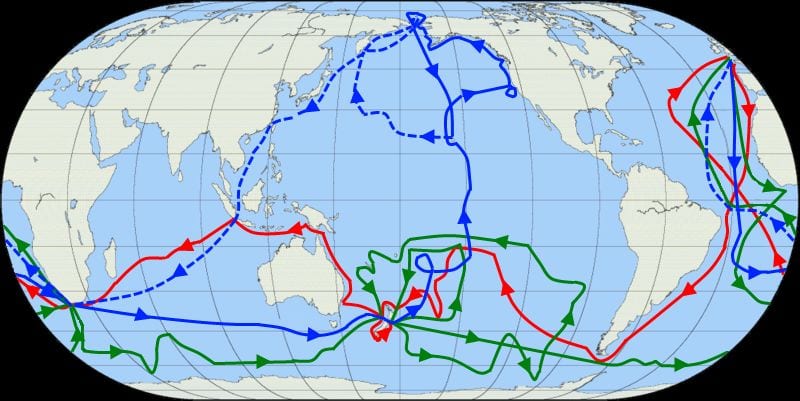

James Cook’s three voyages

First voyage in red, second in green, and third in blue. The route of Cook’s crew following his death is shown as a dashed blue line.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Jon Platek – Accessed 19 March 2021

Outward voyage

HMS Endeavour left Plymouth on 26 August 1768 making provisioning stops at Madeira and Rio de Janeiro. After struggling through gales the ship rounded the Horn and anchored in the Bay of Good Success on the South American Pacific coast where the naturalists enjoyed time collecting before heading to Tahiti, arriving on 10 April 1769 (the third European ship to have called here) in plenty of time to record the transit. There was some collecting in Tahiti but there were other distractions during the three month stay, Banks becoming an ‘Otahitean’ (local name for what is now Tahiti) enjoying the company of the welcoming indigenous people, even receiving a tattoo on his arm and taking a young Tahitian mistress.[2] French Admiral Bougainville, one of the previous callers at the island in 1768, subsequently described in a 1771 travelogue an earthly paradise of innocence, peace, happiness, and sexual freedom that had no doubt fuelled romantic notions of ‘innocent and noble savages’ free from worldly corruption.[13] Cook was to note in his journal that there had been ‘too free use of the women’ and that of his crew ‘half of them had got the venereal disease’.[14]

The ship now headed northwest allowing Cook to survey, name and claim the Society Islands before heading south in search of Terra Australis Incognita along lower latitudes but eventually reaching Aotearoa (then known to Europeans as Staten Landt, now New Zealand), the first European ship to do so since Abel Tasman’s Heemskerck in 1642. Between October 1769 and March 1770 Cook circumnavigated, charted and claimed for Britain the two islands of New Zealand, landing at Poverty Bay in October 1769, a visit that cost several Maori lives. Then, with winter setting in it was decided not to follow the intended route through the high latitudes to the Cape of Good Hope but, instead, to return to Britain via the east coast of New Holland and the East Indies – that is, Batavia, Cape of Good Hope, St Helena.

Point Hicks to Botany Bay

Sailing towards New Holland the first sighting was on 20 April 1770 at Point Hicks (between present-day Orbost and Mallacoota in Victoria and now named after Lieutenant Zachary Hicks, the sailor who first spied land) the Endeavour continuing northward (thus leaving unresolved the question of whether Van Diemens Land was part of the mainland) along the east coast doing a ‘running survey’ until a large bay was spotted.

Botany Bay

On 28 April the anchor was dropped in what Cook called in his diary Sting-Rays Harbour. It was an exciting time for the botanists who reveled in the discovery of the now iconic plant genera Acacia, Banksia, Brachychiton, Callistemon (bottlebrush), Eucalyptus, Grevillea, Isopogon (drumsticks), and Telopea (waratah). To commemorate this memorable moment Cook changed his earlier name to Botany Bay and the enclosing headlands at the entrance Cape Banks and Cape Solander to permanently record the two botanists of the voyage who, over a period of six days had collected about 3,000 plant specimens, challenging the storage capacity of the ship.(E Charles Nelson 1998) To keep the specimens fresh for Parkinson’s illustrations the collections had been stored in tin chests wrapped in damp cloth.[3]

Cook weighed anchor on 7 May briefly noting Port Jackson as he sailed past. By 12 May Parkinson had completed 94 sketches of plants from the bay.[4]

Banksia serrata – Saw Banksia

Iconic Australian plant in the family Proteaceae, a plant family widespread across ancient Gondwana before its separation into continental plates.

Specimen collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander in April 1770 at Botany Bay on Cook’s first scientific voyage of scientific exploration in HMS Endeavour

Courtesy National Herbarium of Victoria

Endeavour River

Continuing up the east coast, charting all the way, naming geographic features such as the Yuin peoples’ Gulaga (named Mt Dromedary) and Didthul (named Pigeon House Mtn). The ship landed briefly at Bustard Bay and unwittingly sailed into the waters between the mainland and Great Barrier Reef. On 11 June the Endeavour struck a reef off present-day Cooktown, puncturing the hull, only escaping by the ingenious method of pulling a sail over the breach. Beaching the ship for repairs at what Cook named Endeavour River gave the naturalists another opportunity for collections, making observations on the strange animals and other natural history as careening and repairs were completed over the next six or seven weeks. Many of the specimens already collected had been saturated as the bread compartment where they were stored had taken in water, so these were laid out to dry and new specimens of the same species collected where this was possible.[5] Plant collections at this site included over 200 species and 190 sketches by Parkinson among which was Toona australis, the Red Cedar, a tree that was later to become the mainstay of the timber industry in the new colony for many years as vast areas of the Queensland and New South Wales coast were cleared. For each collecting spree Solander was to maintain specimen catalogues, drawing up plant descriptions as time permitted. With pressing paper now running out Banks resorted to using unbound sheets of a copy of Milton’s Paradise Lost that he had brought to read on the voyage.[15]

Claims a continent for Britain

Endeavour set off northwards on August 4 and on 22nd of the same month Cook landed on and named Possession Island at the tip of the Cape York Peninsula. Here, to volleys of gunfire, three cheers, and a hoisted Union Jack, Cook claimed in the name of King George III the eastern coastline of New Holland as British territory, calling it New South Wales.

Torres Strait to Batavia

He then proceeded carefully through the archipelago of Torres Strait, limping to Batavia where the ship was again careened and repaired ready for the journey home.

As so often at this port, the crew contracted malaria and dysentery, and over the next 3 months 30 of the crew died, including two Tahitians who died in Batavia after being taken on board in Polynesia.[10] Also, on the way to the Cape of Good Hope, Banks’s assistant Herman Sporing and the artist Sydney Parkinson with both Banks and Solander ill as well, the ship limping home, recuperating for a month at the Cape of Good Hope before docking at Dover on 12 July 1771 almost three years after their departure.[6]

Delay in scientific publication

In the course of the voyage Banks had accumulated around 30,000 specimens of about 3000 species, probably around 1400 new to science, and most of these from Australia.[8]

Solander, using the Linnaean sexual system of classification, had described many of the plants while on board ship, accumulating 25 ‘volumes’ of small cards, one for each plant specimen, not to mention a similar number of volumes for zoological specimens.[8] Back in London Solander revised, ready for publication, the plant descriptions he had worked on during the voyage and then awaited the completion of their associated illustrations.

Banks, probably by 1771, had set aside £10,000 ($1.6M in 2019) to publish the results of the voyage.[9] Unfortunately the project faltered. Banks had planned a massive 14 volumes of descriptions and drawings but he now had many distractions.

Part of the delay may have been the illustrations. Mabberley[9] quotes Wilfrid Blunt (1901–87) before making his own assessment:

‘The fact remains that to place a [Ferdinand] Bauer beside a Parkinson is to be compelled immediately to admit that we are contrasting the work of a genius with that of a very competent and conscientious craftsman . . . as an artist [Parkinson] nor any of those who completed his unfinished task were . . . in the same class as [Claude] Aubriet, [Georg Dionysius] Ehret, or either of the two [Ferdinand and Franz] Bauers’. Banks later embraced the Austrian Bauer brothers, whose work was known to him from 1788 at the latest. Although Parkinson’s work was infinitely superior to any earlier illustrations of Australian plants, with the Australian work of Ferdinand Bauer a few years later came the highest pinnacle of botanical art to be reached before modern times. And Banks, yet again, was behind it.

No sooner had he returned than the planning for a second voyage was underway. Banks’s friend and confidante, King George III, appointed Banks Official Advisor to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – essentially its first Director. By 1778 five hundred plates had been completed, but it had been hoped to include twice this number and in the same year Banks was elected President of the Royal Society, a post he held until his death in 1820. By 1782 only another 200 plates had been prepared and interest had waned. Banks himself published little. Solander had promised Linnaeus specimens from the voyage but these were never sent. Banks’s wealthy friend James Smith acknowledged the delay in publication caused by Banks’s many commitments but also blamed Solander, now a sought-after celebrity in London society, Smith accusing Solander of general ‘dissipation’.[9] Parkinson’s botanical illustrations, which consisted of 412 sketches of New Holland plants, had been retained by the British Museum. Of the sketches 362 were converted to finished drawings of which 340 were made into copper engravings. Only in 1900 were 318 of the latter printed by the museum, effectively the first opportunity for scientists and public to experience what the voyagers had seen on the other side of the world. All-in-all 742 copper plate engravings were made at a cost to Banks of £10,000 but these were not to be published until 1980.

Solander died in 1782 so it was left to later botanists to describe the specimens which, along with Solander’s manuscripts, were freely available at Banks’s home in Soho Square. Botanists who used these specimens included James Smith, Joseph Gaertner, Linnaeus’s son, Robert Brown who became Banks’s librarian after Solander’s death, eventually publishing the monumental Prodromus Florae Hollandiae in 1810. Even so, many of the first descriptions of New Holland plants were needlessly based on collections made after Cook’s first voyage and Solander’s unpublished work was not always acknowledged. William Aiton (Head Gardener at Kew) in his catalogue of plants grown at Kew, Hortus Kewensis, including extracts from Solander’s manuscripts without acknowledgement of their source.[10]

Banksia was first described by a Swede in 1782, Linnaeus’s son Carl, some of the first collected species being described by Spanish botanist Antonio Cavanilles from collections made by Luis Née, naturalist on Alessandro Malaspina’s visit to Port Jackson in 1793; the genus Eucalyptus was first described by a Frenchman Charles L’Heritier in 1788, the first Grevillea by Robert Brown based on a name used by Joseph Knight in his On the Cultivation of Plants Belonging to the Natural Order of Proteeae of 1809. Knight, an eminent nurseryman of the Kings Road, Chelsea in London, had trained the father of William Guilfoyle (Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne from 1873 to 1909) in landscape gardening.[11] The first Callistemon (bottlebrush) to be described in Europe, present-day Callistemon citrinus, was first described as Metrosideros citrina from an illustration in Curtis’s Botanic magazine “ . . . our drawing was made from a plant . . . at Lord Cremornes, the root of which had been sent from Botany Bay; . . .

The second voyage in HMS Resolution (1772-1775)

About a month after returning from his first voyage to the Pacific Cook was promoted to Commander and in November received notification from the Admiralty of a second expedition. Cook’s successful first voyage had captured the public imagination and curiosity about the mysterious great southern land. The Royal Society commissioned two ships to explore further, HMS Resolution, under Cook’s command and HMS Adventure under captain Tobias Furneaux, Cook’s second-in-command.

The Forsters, Anderson & Sparrman

Though productive botanically the significance of these voyages to Australia lie in the nine days spent in Adventure Bay, Van Diemen’s Land (Furneaux for five days in 1773, Cook for four days in 1777) along with an appraisal of the potential of Norfolk Island (briefly visited on 11 October 1774) for possible settlement and as a source of two potentially vital resources – timber for shipbuilding and flax for the British textile factories, essentially to produce the linen for sails and also cordage and ropes for rigging.

Banks was invited to join the team but eventually declined after bickering about his allotted space. Nevertheless he recommended Prussian Johann Forster, a member of the Royal Society, as naturalist for the voyage. Forster’s father was English and was known for his translations of foreign travel. Johann, in turn, chose his 17-year-old son Georg as ship’s artist. By studying the Endeavour collections of Banks & Solander the family duo prepared for what they might encounter. Like those before them the Forsters used Solander’s text in later publications, with little acknowledgement.[1]

The Resolution and Adventure sailed from Plymouth in 1772, putting in at the Cape of Good Hope where they were joined by Swedish botanist Anders Sparrman, a former pupil of Linnaeus. Although there were rich botanical pickings in New Zealand later published by the Forsters in several volumes.[check] Cook did not land in either New Holland or Van Diemens Land but Furneaux, after being separated from the Resolution headed for the Van Diemen’s land’s Storm Bay (named after the storm that had prevented Abel Tasman from landing there 130 years before in 1642) on Bruny Island off the south-east coast.

Adventure Bay

HMS Adventure remained in Storm bay for five days in March 1773 replenishing the water supply and carrying out repairs. Furneaux was to change the name Storm to Adventure Bay, to commemorate his ship, and it would prove a popular anchorage on the way from the Cape of Good Hope to Port Jackson, being later visited by Cook (HMS Resolution 1777), Bligh (HMS Bounty 1788, HMS Providence 1792 ), Bruni d’Entrecasteaux (Recherche 1792, 1792), (Flinders attempted entry in HMS Norfolk in 1798), and Baudin (in the Géographe in 1802), subsequently being used as a base for whaling and the timber industry.

Cook accepted with some reservation, Furneaux’s conclusion that Van Diemen’s Land was part of the mainland. From the Cape of Good Hope Cook sailed into the high latitudes, actually crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time in history, to be confronted by an ice pack at latitude 67o15’, just 120 km short of the undiscovered continent of Antarctica.[2]

Norfolk Island flax and pines

Returning to warmer seas on 11 October 1774 Cook put in to Norfolk Island (one of many islands in the region). Here the flax plant grew more densely than on New Zealand and Cook noted the straight ‘pines’ (Araucaria heterophylla), cutting a sample which was used successfully as a topgallant (cross bar for the small sail at the top of the mast) and concluded that here was a source of sound timber for masts – an observation that had greater commercial implications than any findings and observations made on economic potential of plants growing on New Holland shores.

Cook on his return voyage to New Zealand in 1774 landed three times on the Friendly Islands (Tonga) and also visited Easter Island and Norfolk Island. He mapped and named much of the coastline of New Caledonia, and Vanuatu (at that time the New Hebrides). He returned Resolution to Spithead on 30 July 1775: it had been a three-year odyssey with only one man lost out of 118.

Forsters’ publication

Without the delay that accompanied publication of the findings of the first voyage the Forsters’ botanical account of the voyage was published in 1776.[7]

The Forsters were welcomed at Banks’s house in Soho Square but lack of publication of the findings of the first voyage, so carefully prepared by Solander, meant that many of the South Pacific plants new to science were first described, not from specimens collected on the Endeavour expedition, but from specimens collected by the Forsters on the second voyage and then dispersed among various European institutions where they were accessible to botanists.

The third voyage (1776-1779)

When the ships returned from this second voyage Banks and Smith were quick to buy a duplicate herbarium of the specimens and illustrations collected and produced produced from the voyage.[3]

The scientific world was in awe of Cook’s achievements, but the much lionized and decorated Cook could not acquiesce, setting out yet again in July 1776 with HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery, this time with the major goal of finding the elusive north-west passage, a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic Ocean passing across the northern coast of North America through the tricky Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Storage room was created for some domestic stock and further provisions and fodder loaded at Tenerife and the Cape and provision made for planting vegetables at key landing points. Tahitian Omai (who he had brought back to London from his second voyage) was also to be returned to his homeland. His true name was Mai but the belittling name Omai had become generally accepted.

Cook first returned Omai then set about his main task – but finding the Bering Strait impassable he returned to Hawai’i. By making a further demand for supplies he had outstayed his welcome and, after a series of altercations, was killed by the inhabitants on 14 February 1779.

William Anderson & David Nelson

Naturalists on this last fateful voyage for Cook were surgeon-naturalist William Anderson, and David Nelson a gardener from Kew. Anderson who was Surgeon’s mate on the second voyage was promoted to Surgeon-Naturalist on the third (he was to die on 3 Aug. 1778 while searching for the new passage). The artist to record the voyage was John Webber, remembered for his depictions of Australasia, Hawai’i (then known as the Sandwich Islands where Cook was the first European to make formal contact) and Alaska.

Adventure Bay

Botanical finds on the voyage were made during a four day stay in Adventure Bay from 26-30 January 1777 when plants and seed were collected by the naturalists William Anderson and David Nelson, among the collections being specimens of Eucalyptus obliqua deposited at Kew and from which Frenchman Charles L’Héritier published the first description of the genus Eucalyptus in 1788. While in the bay Anderson made extensive notes on the natural history of the area from Resolution Inlet to Penguin Island, collected live plants of Melaleuca squarrosa for return to England, and planted a small vegetable and fruit garden.[4]

Commentary

For a collective sustainability analysis of the European maritime activity during the Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment see the introductory article coastal navigators.

As a character in the period referred to as the Enlightenment Cook’s life spanned the death of Newton and the birth of Darwin at a time when the Royal Society was gaining political influence. The three voyages had earned him international respect for his navigation and cartography. To the existing knowledge of the Pacific he had added the outline of the east coast of New Holland (intended but not achieved by Abel Tasman in 1644 or Louis de Bougainville in 1766) and New Zealand, discovered New Caledonia, accurately placed a number of island groups and established the limits of any possible southern continent(s). He had contributed to nautical medicine through his treatment of the scurvy that had plagued mariners for centuries, returning from his first voyage without losing a single man to this particular curse (though men were lost to malaria, dysentery, and possibly typhoid); he had applied a long-awaited short-hand way of calculating longitude, testing out John Harrison’s revolutionary marine chronometer on his second voyage, revolutionising the calculation of longitude by calculating a ship’s distance to the east or west of a prime meridian more accurately than ever before[6]; he had travelled further south than any other explorer; pioneered the ‘Great Circle’ route[5] to be followed by so many mariners in the years to come; and, finally, on the second voyage, he had put the myth of the Great Southern Land to rest once-and-for-all. Natural history specimens had been brought back by the thousand giving biology, geology, and anthropology a global dimension. It had been a scientific triumph.

As a commercial venture little was gained. Nothing had been found to rival the sugar plantations of the West indies, the tobacco plantations of Virginia, or the spices of the East Indies – although it was hoped that something could be made of the flax and pines which had unrealized economic potential. Could they feed the hungry textile mills of Yorkshire and Lancaster, and supplement the flagging supplies of timber needed to keep a modern navy afloat?

From all three of Cooks voyages plants were returned to England and introduced into cultivation (see page) his peregrinations leading to the English-speaking occupation of Australia and New Zealand and the acquisition of islands of later strategic importance.

Cook is generally regarded as a heroic British adventurer-explorer and, as such, has accumulated a vast literature. Wikipedia has an excellent account of his achievements and for the more serious historians there are the definitive works of Professor J.C. Beaglehole.

Cook’s reputation as heroic adventurer is today more nuanced. As a representative of a colonial empire he is associated with the fate of native peoples who suffered venereal and other European diseases, were subjected to violence close to genocide and the dispossession of land. Native peoples were almost universally treated with European arrogance that ensured they were either exterminated, confined to missions, reserves, or other forms of containment, and either reduced to the status of the lowliest members of society or totally ignored. In 2019 the First People of Australia still have no recognition in the country’s constitution.

Cook was a social celebrity into the 1780s. The last official account of his voyages was published in 1784 and he remains one of Britain’s most revered historical figures. There was money to be made in the journals of seafaring adventure and journals by unofficial authors (such as that of the second voyage, written by Johann R. Forster) were sometimes suppressed by the Admiralty.

Cook’s wife Elizabeth, who survived him by several decades, is known to have retained, distributed, or destroyed many of Cook’s drafts of his journals and maps.

Cook had shown that New Zealand consisted of two fertile islands suitable for colonization; that New Guinea was separate from the mainland, as was Espiritu Santo (the largest island of present-day Vanuatu); that the east coast of New Holland was more verdant that the other coasts that had been so repellant to the Dutch. He had also shown that there was a large area of the Southern Ocean that was not occupied by a Terra Australis Incognita.

In the course of the voyage Banks and his naturalists had accumulated 30,382 natural history specimens representing 900 Australian species, of which 331 were plants. Parkinson managed to draw or paint more than 1300 works, mostly while the Endeavour steadily charted the east coast.[7]

Banks had intended to put together an extensive account of the natural history of the voyage and naturalists world-wide eagerly awaited the publication of what would be a glorious celebration of the most successful scientific voyage of exploration so far in the Age of the Enlightenment. Banks had employed an impressive team of draughtsmen, under Solander’s supervision, to work up Parkinson’s 950 plant sketches ready for copper plate engraving. Unfortunately it was to be a long wait.

Sadly, descriptions of the new plants were to appear bit by bit often in horticultural periodicals, many of them actually described from collections made by other botanists at a later date. It was only with the much later work of Robert Brown that some of the backlog was to be completed. First plant descriptions from the voyage appeared in Smith & Sowerby’s A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland (1793-95).

Banks did not return to New Holland but was an influential government advisor on political and scientific appointments and general matters concerning the new colony while at the same time retaining a keen botanical interest, receiving specimens from ships surgeons, governors, and residents while also financing botanical and horticultural collectors.

Fortunately Banks’s herbarium was not split up and in 1827, after Banks’s death in 1820, Brown transferred these to the British Natural History Museum: they number about 23,400 specimens.

Although Cook no doubt enjoyed the exuberance of the botanists during the voyage he wryly admitted that prospecting for plants of economic importance had proved a disappointment:

‘The Land naturly [sic] produces hardly any thing fit for man to eat and the Natives know nothing of Cultivation’.[12]

. . . a statement that echoed the sentiments of Dampier many years before.

Cook was a social celebrity into the 1780s, the last official account of his voyages published in 1784 and he remains one of Britain’s most revered historical figures. There was money to be made in the journals of seafaring adventure and journals by authors such as that of the second voyage, written by Johann R. Forster, were suppressed by the Admiralty.

Cooks wife Elizabeth who survived him by several decades is known retained, distributed, or destroyed many of Cook’s drafts of his journals and, maps.

Cook had shown that New Zealand consisted of two fertile islands suitable for colonization; that New Guinea was separate from the mainland, as was Espiritu Santo (the largest island of present-day Vanuatu); that the east coast of New Holland was more verdant that the other coasts that had been so repellant to the Dutch. He had also shown that there was a large area of the Southern Ocean that was not occupied by a Terra Australis Incognita.

In the course of the voyage Banks and his naturalists had accumulated 30,382 natural history specimens representing 900 Australian species, of which 331 were plants. Parkinson managed to draw or paint more than 1300 works, mostly while the Endeavour steadily charted the east coast.[7]

Banks had intended to put together an extensive account of the natural history of the voyage and naturalists world-wide eagerly awaited the publication of what would be a glorious celebration of the most successful scientific voyage of exploration so far in the Age of the Enlightenment. Banks had employed an impressive team of draughtsmen, under Solander’s supervision, to work up Parkinson’s 950 plant sketches ready for copper plate engraving. Unfortunately it was to be a long wait.

Sadly, descriptions of the new plants were to appear bit by bit often in horticultural periodicals, many of them actually described from collections made by other botanists at a later date. It was only with the much later work of Robert Brown that some of the backlog was to be completed. First plant descriptions from the voyage appeared in Smith & Sowerby’s A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland (1793-95).

Banks did not return to New Holland but was an influential government advisor on political and scientific appointments and general matters concerning the new colony while at the same time retaining a keen botanical interest, receiving specimens from ships surgeons, governors, and residents while also financing botanical and horticultural collectors.

Fortunately Banks’s herbarium was not split up and in 1827, after Banks’s death in 1820, Brown transferred these to the British Natural History Museum: they number about 23,400 specimens.

Although Cook no doubt enjoyed the exuberance of the botanists during the voyage he wryly admitted that prospecting for plants of economic importance had proved a disappointment:

‘The Land naturly [sic] produces hardly any thing fit for man to eat and the Natives know nothing of Cultivation’.[12]

Simple timeline of three voyages

1768-1771: First Voyage

1768: Departure from England.

1769: Reached Tahiti; Observed the Transit of Venus.

1769: Explored Society Islands; Botanical discoveries: Breadfruit, Tiare Gardenia.

1770: Charted New Zealand; Botanical discoveries: Flax (Harakeke).

1770: Landed in Australia; Botanical discoveries: Banksia, Eucalyptus, Acacia.

1772-1775: Second Voyage

1772: Departure from England.

1773: Crossed Antarctic Circle; Discovered South Georgia Island.

1773: Explored Easter Island; Botanical discoveries: Toromiro, Yams.

1774: Explored Tonga; Botanical discoveries: Kava, Coconut.

1774: Explored New Zealand; Botanical discoveries: Pohutukawa, Tree Ferns.

1776-1779: Third Voyage

1776: Departure from England.

1777: Explored Tahiti; Further studied breadfruit cultivation.

1778: Charted Hawaiian Islands; First European contact with Hawaii.

1778: Explored Pacific Northwest; Botanical discoveries: Sitka Spruce.

1779: Killed in Hawaii; Botanical discoveries: Metrosideros polymorpha (ʻŌhiʻa).

Key points

Cook’s three circumnavigations of the world from 1768 to 1780 included his now famous exploration of the Pacific.

The product of Enlightenment ideas Cook included scientists, artists and other naturalists on his voyages of discovery. He connected Europe with peoples on the opposite side of the world but by claiming lands for Britain he heralded native dispossession.

His nautical achievements included:

- a map of New Zealand

- charting of the east coast of Australia

- confirmation that the Great South Land terra australis did not exist

- searched for the northwest passage to Asia and confirmed Bering’s discoveries in the Arctic

- documented flora and fauna and completed other scientific investigations including the recording of the transit of Venus

- European discovery of Hawaii and other Pacific Islands

- Confirmed the effectiveness of anti-scorbutics in the battle with scurvy

- Advanced the state of navigation & cartography

Media Gallery

The Amazing Life and Strange Death of Captain Cook: Crash Course World History #27

Crash Course – 2012 – 10:32

Wikipedia

Dharawal elder recounts Captain Cook’s arrival in Australia 250 years ago

James Cook (Documentary)

*—

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . revised 19 March 2021

. . 29 July 2023 – minor edit

HM Bark Endeavour – Replica in Darling Harbour, Sydney – 2013

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Hpeterswald – Accessed 10 January 2021