European navigators

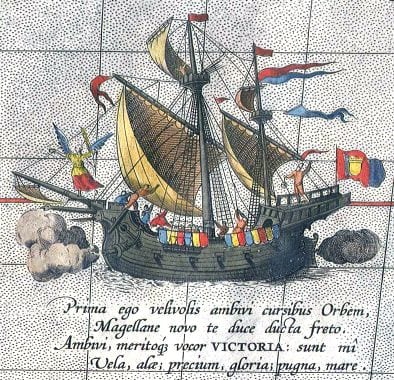

On the first circumnavigation of the world from 1519 to 1522

Magellan was killed in the Philippines in 1521

Detail from map Maris Pacifici by Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Introduction – European Navigators

We do not know what Aboriginals called the continent we now know as Australia,[6] or even if they were aware that it was a vast island. Records of Aboriginal water trade are meagre, the watercraft, mostly for fishing, were rafts of logs, reeds, bark, and simple dugout wooden canoes that were sufficient to meet small-scale local needs.[7]

Water-based trade is strongly associated with the elaboration of technology and social organization. European colonial expansion – riverine and maritime exploration and trade – can be traced back to its Mesopotamian core and the commerce that developed between the civilizations along the Tigris, Euphrates and Nile river-valleys. In Asia it occurred along the valleys of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers where settled communities developed the trappings of civilization. In Europe, river trade expanded into the Mediterranean as a trading arena for Minoan, Mycenean, Phoenician, then Greco-Roman civilizations. In Roman times there had been limited contact with India across the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea and Alexandria.

From antiquity came the assumption that there was a large land mass to the south that balanced the mass of the land in the north, referred to in classical times as Terra Australis Nondum Cognita (southern land not yet known), generally abbreviated to Terra Australis.

At the end of the 15th century Columbus had crossed the Atlantic (over 100 years after a small Viking settlement was made on America’s northern coast) launching a new age of maritime exploration and trade. Portuguese and Spanish explorers, buoyed by finds of gold and silver in the Americas, then rounded the Cape of South Africa to cross the Indian Ocean and thence to the Pacific in the first circumnavigation of the globe. So, by 1520 Portuguese ships had penetrated the islands to the north of a land they called Java la Grande.

Private companies, like the Dutch and British East India Companies forged trading links across the world, even assembling armed navies, and sometimes assuming the role of government, issuing coinage etc. notably the British in India and Dutch in the East Indies. Trading by these companies, forerunners to today’s multinational corporations, gave rise to the modern stock exchange and global economy. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was incorporated by English Royal Charter in 1670 and, for nearly 200 years, functioned as the government in parts of North America until the land it owned (the Hudson Bay drainage Basin) was sold to Canada in 1869. Trading fur for much of its existence, throughout much of the English- and later British-controlled North America, HBC now manages retail stores in Canada and the United States.

For Europeans the Pacific was the last major maritime frontier.

Then, with changing political fortunes, it was Dutch ships of the VOC (Dutch East India Company), often blown off course, that made most frequent coastal contact with this southern land that they called Nova Hollandia (New Holland).

Even the French, through explorer Baudin, left their mark by briefly claiming the southern coast as Terre Napoleon.

The Pacific

European maritime exploration of the Pacific began in about 1500, preceding Australian settlement (1789) by nearly 300 years (longer than the post-settlement period).

This maritime activity occurred during the European Age of Discovery and Exploration dominated by the Spanish and Portuguese (1488-1522) – their search for precious metals and desire to spread the Christian gospel to native peoples. This was followed by a Dutch golden age of commercial expansion (c.1600-1700) then British and French ascendancy (c.1750-1820) during the Age of Enlightenment dominated by a hopeful intellectual class keen for social and political change based on humanism, science, logic, and reason.

The many advantages to be gained by expanding colonial empires, establishing new trade routes, and extending diplomatic and trade relations to new territories, were abundantly clear. With the advent of printing and wider access to ancient texts intelligent readers could see that this had been a successful formula for the ancient Mediterranean empires, especially the Romans, whose legacy of culture, buildings and infrastructure could be seen across Europe.

The Pacific was Europe’s last major geographic frontier. With vast fortunes already made from the spice trade, speculation was rife concerning the presence of yet unknown treasures still to be found. Would there be economically important botanical treasures like the precious metals, maize, potato and tobacco that had been found by the Spanish and Portuguese in the Americas?

Spain and Portugal were the European maritime powers in the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal acquiring trading territory in Timor, Indonesia and New Guinea places where they would also send missionaries. However their declining fortune saw the rise of a new world economic and sea power: it was the Dutch Golden Age as territories were overrun and this region became known as the Dutch East Indies.[1] As trade between Europe and the Dutch East Indies increased, there was corresponding speculation about the commercial potential of Terra Australis Incognita to the south.

Early European based ‘monopoly companies’ trading in Asia included the Portuguese Estado da India (first monopoly of this kind), the Muscovy, the Ostend, the Swedish, the English East India Company and the VOC (Dutch East India Company), the latter by far the most significant in early Australian maritime history by placing this southern continent on the world map well before the better-known English seafarers Dampier, Cook and Flinders. Of the 54 recorded European ships that sailed into Australian waters before 1770, 42 were VOC ships. “Sloepie” was the first ship constructed on the continent by Europeans and it was built by a shipwrecked VOC crew. The first European immigrants, Wouter Loos and Jan Pelgrom De Bye, were convicted criminals, abandoned on the mainland in 1629 as ex VOC employees.[5]

The first exploration of this unknown land occurred in the context of the commercial interests of the Dutch East India Company which, for about 150 years, controlled trade in the region to the north of the future of Australia. After a circumnavigation of the continent by VOC employee Abel Tasman the new land was deemed of little commercial value and any thought of future activity there was abandoned. Dutch claims of possession were not followed up by settlement and subsequent visits were by the new European powers of the 17th and 18th centuries, Britain and France, driven not only by political and commercial interests but a new and fashionable interest among the social elite in science and learning. Over time Dutch interest waned. Abel Tasman’s reconnaissance of the region in the mid 17th century had concluded that the region offered few commercial, or indeed any other, prospects. With diminishing Dutch political and economic influence it was left to the ascendant Britain and France in the 18th century to exert European influence in the region with navigator James Cook finally dispelling the myth of a vast undiscovered southern land mass.

Cartography and reconnaissance

The task was one of exploration and cartography – to delimit the boundaries of this unknown southern land by the hazardous and painstaking process of coastal mapping while, at the same time, making observations on its resources, making contact with any inhabitants and assessing their willingness to trade.

Dutch resourcefulness through the period 1640 to 1760, and especially Abel Tasman’s voyages, defined the outline of the region. Terra Australis became New Holland (Hollandia Nova, a name given by Tasman in 1644 and retained for 180 years until ‘Australia’, proposed by Flinders, was officially sanctioned by Britain in 1824). Tasman also ‘discovered’ and named Staten Landt (New Zealand), Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), as well as Fiji and New Guinea. After his voyages the search for Terra Australis Incognita moved into higher latitudes below the southern coast of Staten Landt.

Illustration – Roger Spencer – 2014

With vast fortunes already made from the spice trade of the Banda Islands in the East indies, speculation was rife concerning the presence of yet unknown treasures still to be found in lands unfamiliar to the European. Could there still be economically important botanical or other treasures like the precious metals, maize, potato and tobacco that had been found by the Spanish and Portuguese in the Americas? Many of the early explorers and collectors were medical men, French and English naval surgeons.[2]

Spain and Portugal were the European maritime powers in the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal acquiring trading territory in Timor, Indonesia and New Guinea – places where they would also send missionaries. However their declining fortune saw the rise of a new world economic and sea power: it was the Dutch Golden Age (see … for more of the cultural and political background to this phase of history) territories were overrun and this region became known as the Dutch East Indies.[1] As trade between Europe and the Dutch East indies increased, there was increasing speculation about the commercial potential of the Terra Australis Incognita to the south.

The first exploration of this unknown land occurred in the context of the commercial interests of the Dutch East India Company which, for about 150 years, controlled trade in the region to the north of the future of Australia. After a circumnavigation of the continent by VOC employee Abel Tasman the new land was deemed of little commercial value and any thought of future activity there was abandoned. Dutch claims of possession were not followed up by settlement and subsequent visits were by the new European powers of the 17th and 18th centuries, Britain and France, driven not only by political and commercial interests but a new and fashionable interest among the social elite in science and learning. Over time Dutch interest waned. Abel Tasman’s reconnaissance of the region in the mid 17th century had concluded that the region offered few commercial, or indeed any other, prospects. With diminishing Dutch political and economic influence it was left to the ascendant Britain and France in the 18th century to exert European influence in the region with navigator James Cook finally dispelling the myth of a vast undiscovered southern land mass.

The task was one of exploration and cartography – to delimit the boundaries of this unknown southern land by the hazardous and painstaking process of coastal mapping while, at the same time, making observations on its resources, making contact with any inhabitants and assessing their willingness to trade.

Dutch resourcefulness through the period 1640 to 1760, and especially Abel Tasman’s voyages, defined the outline of the region. Terra Australis became New Holland (Hollandia Nova, a name given by Tasman in 1644 and retained for 180 years until ‘Australia’, proposed by Flinders, was officially sanctioned by Britain in 1824). Tasman also ‘discovered’ and named Staten Landt (New Zealand), Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), as well as Fiji and New Guinea. After his voyages the search for Terra Australis Incognita moved into higher latitudes below the southern coast of Staten Landt.

Though the Dutch made the first observations on the vegetation, possibly making the first plant collections in the new land it was, however, the later British and French who began the meticulous process of plant collection, classification, naming, and documentation. In the 1780s England’s main overseas empire was India rather than North America and in wartime its merchant ships had to manouvre the 9000 km journey with ponly one friendly stop at the island of St Helena in the south Atlantic. The Dutch held the African Cape of Good Hope and the French Mauritius and Reunion both in highly strategic localities prompting the British occupation in 1786 of the coral atoll Diego Garcia halfway between Mauritius and Sri Lanka. Trade routes dictated the consumption of tea and coffee in Europe. English tea drinkers were supported by a vibrant trade in tea that passed from southern China through the East indies and sometimes Penang (founded as a British port in 1786) and past Africa while the French drank coffee from the West Indies.[3]

Strategically a port at Botany Bay would prove a valuable Pacific provisioning centre for whaling vessels and ships on their way to the Chinese tea ports and the fur seal trade in north-west America, as well as providing access to the potential flax on Norfolk Island not to mention the possibility of ships masts constructed from the many straight Norfolk island Pines, Araucaria heterophylla also growing on the island (see Norfolk Island Pine). Britain at that time depended on sails and ropes made from flax imported from the easily blockaded Baltic. The French were aware of British intentions and in 1785 La Pérouse had been instructed to collect living specimens for return to France.[4]

Table showing Dutch voyages making botanical observations; English, Spanish and French voyages of scientific exploration that made landfall in New Holland. [dates and places of landing?]

| DATE/PLACE | SHIP | COMMANDER | BOTANIST/NATURALIST |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1642-1643 | Heemskerck, Zeehaen | Tasman | Three brief landings. Ship loaded with goods for sale or barter |

| 1 Dec,1642 Visscher Is | |||

| 1644- | Limmen, Zeemeeuw, Braek | Tasman | |

| 1686-1691 | Cygnet | Dampier | Dampier as crew member |

| 1696-1698 | De Geelvink, De Nijptang, Weseltje | Vlamingh | |

| 1699-1701 | Roebuck | Dampier | Dampier making natural history observations |

| 1768-1771 | Endeavour | Cook | Banks, Solander |

| 1772 | Du Fresne & Crozet | ||

| ?Cape Fred Hendrick | |||

| 1772-1775 | Resolution | Cook | W Anderson, JR & JG Forster, Sparrmann, Masson (passenger) |

| 10-15 Mar. | |||

| Adventure Bay | Adventure ?Discovery | Furneaux | |

| 1776-1779 | Resolution | Cook | Anderson |

| Discovery | Clerke | Nelson* | |

| 1785-1788 | Boussole | La Perouse | Prévost (ygr), Collignon* |

| Astrolabe | La Martiniére, Prévost (uncle) | ||

| 1787-1790 | Bounty | Bligh | Nelson* |

| 22 Aug 1788 | |||

| Adventure Bay | |||

| 1789 | Hunter | ||

| Adventure Bay | |||

| 1789 | Cox | ||

| Coxs Bight, Oyster Bay | |||

| 1789-1793 | Atrevida, Descubierta | Malaspina | Née, Haenke |

| 1791-1794 | Recherche | DEntrecasteaux | Labillardière, L. Ventenat, Delahaye* |

| Feb 1793 Recherche Bay | Riche | ||

| Espérance | Kermadec | ||

| 1791-1795 | Discovery, Chatham | Vancouver | Menzies |

| 1791-1793 | Providence & Assistant | Bligh | James Wiles*, Christopher Smith* |

| 9-24 Feb 1792 | |||

| Adventure Bay | |||

| 1800-1804 | Géographe | Baudin | Leschenault, Riedlé,* Sautier,* Guichenot* |

| Michaux, Delisse | |||

| Naturaliste | Hamelin | Cagnet,* Merlot* | |

| Casuarina (Sydney 1802) | Freycinet | ||

| 1801-1805 | Investigator | Flinders | Brown, Good,* Bauer |

| 1817-1820 | Uranie | Freycinet | Gaudichaud |

| [Physicienne] | [Guichenot] | ||

| 1822-1825 | Coquille | Duperrey | DUrville, Lesson |

| 1824-1826 | Thétis, Espérance | Bougainville | Busseuil |

| 1826-1829 | Astrolabe (Coquille) | DUrville | Lesson, Gaimard |

| 1831-1836 | Beagle | Fitzroy | Darwin |

| 1836-1837 | La Bonite | Vaillant | Gaudichaud |

| 1837-1840 | Astrolabe (Coquille), Zélée | DUrville | Hombron |

* = gardener-botanist

† = botanical artist

Plants

Though the Dutch made the first observations on the vegetation, possibly making the first plant collections in the new land it was, however, the later British and French who began the meticulous process of plant collection, classification, naming, and documentation.

TABLE – Dutch voyages making botanical observations. English, Spanish and French voyages of scientific exploration that made landfall in New Holland including dates and places of landing

* = gardener-botanist

† = botanical artist

Age of Discovery

By the early 17th century Spanish and Portuguese seafarers had opened up much of the world to European experience, charting sea lanes to southern Africa, the Americas (New World), Asia, and Oceania. Searching for a sea route to India Bartholomew Diaz had, in 1488, sailed eastward around the Cape of southern Africa to be followed by Vasco da Gama in 1497 who continued to India itself.

Spanish & Portuguese – 1488-1522

Determined to find a western route to the spice islands Christopher Columbus, from 1492-1504, made four journeys across the Atlantic preparing the way for European colonisation of the New World; then, from 1519–1522, Ferdinand Magellan (who died en route in ) commanded an expedition that sailed westward across the Atlantic, then round the foot of South America at Cape Horn and on into a new body of water that he named the Pacific Ocean, then forging on in the same direction to complete the first circumnavigation of the Earth and demonstrate beyond any doubt that the Earth was essentially a sphere.

The history of Portuguese exploration may seem remote and dwarfed by the activities of Columbus and the Spanish. But it was Portuguese sailors who made major advances in the methods navigation, trade and maritime technology, making maximium use of the Atlantic trade winds, sending Vasco da Gama to India and eventually opening up the Far East to Europeans by being the first to reach the mysterious and lucrative spice islands in the Banda Sea, a discovery that initiated the first the first Europeans since Alexander the Great to found an Asian empire but reaching further, and this time making it the first of several European maritime empires.

Over a period of about thirty years ruthless and religiously fanatical Portuguese buccaneers assumed control of the Indian Ocean, breaking the Islamic hold on world trade, setting the precedent for 500 years of European colonisation and initiating the preconditions for globalisation. As early as 1511 Portugal had annexed the Aru Islands and Timor sending Dominican missionaries into the islands just north of Australia.

The Dutch Golden Age – c.1600-1700

For Australia-to-be. the Age of Discovery and Exploration had established trading posts in the East Indies to its north. But political fortunes in Europe were changing as Dutch science, trade and art were the most admired in Europe. In the Pacific Holland was determined to wrest control of the spice trade from the Portuguese. Though in the early Spanish and Portuguese phases dominated by the lure of spices and precious metals and the opportunity to gain souls for Christianity, had always contained the element of adventurous curiosity. Dutch interests, through the Dutch East India Company in Batavia (Jakarta), were strongly commercially centred but their forays by Tasman and others did include accounts of the people, animals and plants.

In 1644, more than 120 years before Cook’s visit to New Holland, the Dutch had assembled a provisional chart of all but the east coast of Australia, including Van Diemens Land and a portion of New Zealand, thus providing a cartographic framework that would prove vital for the botanical and scientific exploration that would follow. The Dutch as contributing to Australian history and yet they made the first undisputed European sighting of Australia

Dutch interest in New Holland was more commercial than scientific but this phase of Australian history did result in a Dutch botanical legacy that included: the first description of Australian vegetation (Tasman 1642); the first scientifically named Australian plants (Burman 1768); and the first indubitable record of seeds of Australian plants reaching Europe (Vlamingh 1698).[6]

Visits to New Holland by Englishman William Dampier in the period 1688 to 1699 stirred the Dutch East India company into renewed navigational forays to the north coast but most of these met unfortunate endings and by 1756 Dutch interest in the region was over. With three ships Tasman charted in detail the southern coast previously covered by Thijssen in 1627, from Cape Leeuwin (discovered by the Dutch ship Leeuwin five years before) all the way to Nuyts Archipelago, some 1800 km to the east, including a landing on Rottnest Island.

Tasman’s names New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land have not survived time but bear witness to his discoveries. He had travelled further south than any other seafarer, the European who discovered Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), Staten Landt (New Zealand), and Fiji. His charts provided the first broad outline of Australia’s northern, western and southern coasts. With a rather dismal impression of New Holland European interest waned for more than 50 years until visited again, this time by an educated English pirate, William Dampier.

These pre-Enlightenment voyages left little botanial legacy compared with the voyages of scientific exploration that would follow.

Age of Enlightenment

It had been the glitter of treasure and the fortunes to be made from spices that drew out the maritime adventurers. But with the European Enlightenment came a new curiosity about the world, its peoples, animals, plants, and natural history, as intellectuals advanced the virtues of reason and science.

In England, under the influence of Joseph Banks, it would be economic botany that would occupy the empire. From the colonies came cocoa, sugar, quinine, coffee, tea, cotton, timber, and ornamental plants many processed into other products – cocoa for chocolate, timber for ships and so on: tropical crops plants like the breadfruit were exchanged across hemispheres east and west, Caribbean to East Indies . . . and elsewhere. Passing in the other direction from Britain to these colonies went the food plants of Europe, the familiar cereals, root crops, fruits, herbs, as well as domesticated animals, that they had known in Britain since the Neolithic, supplemented mostly by the Roman food plants brought to Britain during its occupation.

It was a time when science flourished as never before, the old natural history splintering into a plethora of new disciplines and sub-disciplines. Starting with the expeditions themselves there was the cartography, hydrography, hydrology, meteorology, and astronomy along with improvements in navigation techniques and shipbuilding. Animals and plants shipped back to Europe in their thousands needed description and classification not only with botany, and zoology, but ichthyology, conchology and many more ‘ologies – all contributing to the sense of ‘improvement’ and ‘progress’ that characterized the Enlightenment.

There was now a robust community of scientists: members of new learned scientific societies like the Royal Society in London. They were contributors to new scientific journals, a rush of books, encyclopaedias and compendia of lists and knowledge, an increased scientific rigour. As a period of European collection around the world government naturalists began accumulating specimens in public museums like the British Museum rather than working under patronage to fill the curiosity cabinets of wealthy dilettantes.

It was only with the arrival of the Enlightenment (c.1675-1800) and the scientific, (and especially plant) obsession of the British and French that the systematic collection, description and analysis of specimens began in earnest. It was a new motive for exploration supplementing the old religious, commercial and political motives of the past .

The French

English domination of Australia today can easily overshadow the achievement of French science in the early days of the continent. When itemised we understand both how similar and how closely run were the goals of the two countries. It was France that produced the first complete navigational chart of the country’s coast. The first European garden on mainland Australia was almost certainly the vegetable garden, known as the ‘French Garden’, constructed at Botany Bay between 26 January and 10 March in 1788 (shortly ahead of similar vegetable gardens created by the British settlers at Port Jackson) and, presumably overseen by gardener-botanist from the Jardin du Roi in Paris, Jean-Nicolas Collignon. It was French scientists who first described many iconic Australian plants and animals including the eucalypt, wombat, platypus and emu.

At Josephine‘s Malmaison in Paris Australian animals like the kangoroo (collected on Kangaroo Island during the Baudin expedition) and black swans were placed on display along with a collection of ethnographic artefacts purchased from George Bass. Josephine’s garden A L’Anglais not only revitalised European interest in roses but plants, collected personally by her gardener Felix Delahaye (the only gardener of this period to return to Europe) in Tasmania on the D’Entrecasteaux expedition of 1791-1794 and cultivated in her garden, were illustrated by the world’s possible greatest-ever botanical illustrator, Pierre Redoute. Redoute, the ‘Raphael of flowers’ was court artist to Marie Antoinette when Paris was the cultural and scientific centre of Europe during a golden age of botanical illustration (1798 – 1837) that was part of the phenomenon of ‘botanophilia‘. From this voyage came the first extended account of the continent’s plants by the voyage’s botanist Jaques-Julien Labillardière whose 7 kg Novae Hollandiae Plantarum Specimen was published between 1804 and 1807, containing 265 black and white engravings by artist Pierre Antoine Poiteau. The subsequent Baudin expedition of 1800-1804 was the best equipped and most ambitious of all the Enlightenment voyages of scientific exploration, supported by Napoleon and returning far greater scientific specimens to Europe than any other, though at great human cost.

English

Although Dampier’s accounts included astute observations of New Holland biota it was undoubtedly Cook and Banks who captured the imagination of public and scientists alike and stimulating the French to mount similar expeditions. Above all it was Banks’s ability to coordinate a vast international network of scientists, politicians and royalty that provided some unity of purpose to this enterprise. He was known and respected by not only the English scientists (from members of the Royal Society to his familiarity and patronage of the gardener-botanists that travelled on the expeditions, but internationally by French, German and Russian royalty, French scientists including botanist Labillardière and the socially influential Empress Josephine). In England even parliament and the King George III would defer to his authority. He was the unspoken fatherly coordinator of a global scientific Renaissance that for over 100 years centred on maritime exploration.

Dampier was the first person to circumnavigate the world three times, visiting the Australia-to-be twice in the process. He made the first fully authenticated plant collections in New Holland, and was the first to give a wide-ranging account of the country’s natural history and people although his overall impressions were inagreement with the sentiments of the Dutch mariners that had preceded him. His escapades were the source of inspiration for Danial Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Coleridge’s poem Rime of the Ancient Mariner. His accounts were to be standard reading for all the subsequent voyages of scientific exploration.

When Britain’s political fortunes changed there was the opportunity to learn from the colonial experiences of Spain, Portugal, and Holland. Cook and Banks, when sailing on HMS Endeavour, had called in for provisions at the Dutch port at Cape Town, which impressed the 28-year-old Banks.

Cook had shown that New Zealand consisted of two fertile islands suitable for colonization; that New Guinea was separate from the mainland, as was Espiritu Santo (the largest island of present-day Vanuatu); that the east coast of New Holland was more verdant that the other coasts that had been so repellant to the Dutch. He had also shown that there was a large area of the Southern Ocean that was not occupied by a Terra Australis Incognita.

In the course of the voyage Banks and his naturalists had accumulated 30,382 natural history specimens representing 900 Australian species, of which 331 were plants. Parkinson managed to draw or paint more than 1300 works, mostly while the Endeavour steadily charted the east coast.[7]

Banks had intended to put together an extensive account of the natural history of the voyage and naturalists world-wide eagerly awaited the publication of what would be a glorious celebration of the most successful scientific voyage of exploration so far in the Age of the Enlightenment. Banks had employed an impressive team of draughtsmen, under Solander’s supervision, to work up Parkinson’s 950 plant sketches ready for copper plate engraving. Unfortunately it was to be a long wait.

Sadly, descriptions of the new plants were to appear bit by bit often in horticultural periodicals, many of them actually described from collections made by other botanists at a later date. It was only with the much later work of Robert Brown that some of the backlog was to be completed. First plant descriptions from the voyage appeared in Smith & Sowerby’s A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland (1793-95).

Banks did not return to New Holland but was an influential government advisor on political and scientific appointments and general matters concerning the new colony while at the same time retaining a keen botanical interest, receiving specimens from ships surgeons, governors, and residents while also financing botanical and horticultural collectors.

Fortunately Banks’s herbarium was not split up and in 1827, after Banks’s death in 1820, Brown transferred these to the British Natural History Museum: they number about 23,400 specimens.

Although Cook no doubt enjoyed the exuberance of the botanists during the voyage he wryly admitted that prospecting for plants of economic importance had proved a disappointment:

The Land naturly [sic] produces hardly any thing fit for man to eat and the Natives know nothing of Cultivation.[12]

A product of the Enlightenment, Cook’s life spanned the death of Newton and the birth of Darwin at a time when the Royal Society was gaining political influence. The three voyages had earned him international respect for his navigation and cartography. To the existing knowledge of the Pacific he had added the outline of the east coast of New Holland and New Zealand, discovered New Caledonia, accurately placed a number of island groups and established the limits of any possible southern continent(s). He had contributed to nautical medicine through his treatment of the scurvy that had plagued mariners for centuries, returning from his first voyage without losing a single man to this particular curse; he had applied a long-awaited short-hand way of calculating longitude, testing out John Harrison’s revolutionary marine chronometer on his second voyage, revolutionising the calculation of longitude by calculating a ship’s distance to the east or west of a prime meridian more accurately than ever before[6]; he had travelled further south than any other explorer; pioneered the ‘Great Circle’ route[5] to be followed by so many mariners in the years to come; and, finally, on the second voyage, he had put the myth of the Great Southern Land to rest once-and-for-all. Natural history specimens had been brought back by the thousand giving biology, geology, and anthropology a global dimension. It had been a scientific triumph.

As a commercial venture little was gained. Nothing had been found to rival the sugar plantations of the West indies, the tobacco plantations of Virginia, or the spices of the East Indies – although it was hoped that something could be made of the flax and pines which had unrealized economic potential. Could they feed the hungry textile mills of Yorkshire and Lancaster, and supplement the flagging supplies of timber needed to keep a modern navy afloat?

From all three of Cooks voyages plants were returned to England and introduced into cultivation (see page) his peregrinations leading to the English-speaking occupation of Australia and New Zealand and the acquisition of islands of later strategic importance.

Thwarted on his first expedition William Bligh was, following Banks’s recommendation to the Admiralty, directed for a second time to transplant bread-fruit from Tahiti to the West Indies. He set out in Nov. 1791 in command of HMS Providence with a small brig HMS Assistant commanded by Lt Nathaniel Portlock – and this time he was successful, faring better with the crew but he managed to fall out with midshipman Matthew Flinders, one of Cooks former crews.

Joseph Hooker could not praise Brown’s voyage enough saying that it was ‘ … the most important in its results ever undertaken’ and stating in 1859 of Brown’s Prodromus … that it ‘… has for half a century maintained its reputation unimpugned, of being the greatest botanical work that has ever appeared’.[28]

Botanically, Brown’s Prodromus … of 1810, though imcomplete, was an outstanding work preceded in publication by Labillardiere’s Novae Hollandiae Species Plantarum … of 1804-1807. Some 30 years after the collections of Banks and Solander, those of Robert Brown constitute the largest collection of plants from Australian shores during this period and the first recorded collections from the southern coast. His Prodromus was a true botanical exploration of relationships as well as a listing of taxa,[20] it remained the major source on Australian plants until the monumental six volume Flora Australiensis of Bentham and Mueller (1863-1878).

Flinders’s charts completed the continental coastline while also confirming that New Holland and New South Wales was a single landmass; they were used for many years after his death although, because of the time spent in detention in Mauritius, it was the French who, in 1807, were the first to produce a detailed map of the Australian continental coast. Flinders’s completed work was back in England by 1805 finally published as A Voyage to Terra Australis in Jan. 1814 the day before Flinders died: it contains 16 maps, landscape paintings and sketches by William Westall, and 10 botanical paintings by Ferdinand Bauer. In the Introduction Flinders notes his preference for the name Australia ‘… when speaking of New Holland and New South Wales, in a collective sense’.[30] English names steadily replaced French names except for those parts that Baudin had surveyed and Flinders had not seen, as on the west coast.

With the voyage of the Investigator we see the end of European maritime exploration in Australia: further voyages, like that of Darwin in the Beagle were made essentially as visiting observers. Charting would continue following the release of men and ships after the Napoleonic wars, starting with Philip Parker King’s coastal survey in 1820 – but this was now essentially the work of Australian residents.

Inland exploration continued the maritime tradition of prioritizing plant collection.

Plant commentary & Sustainability Analysis

The Agricultural Revolution had provided the energy of cultivated crops to power population growth and the increase in social organisation required to construct cities and the basic elements of modern arts and sciences. Hierarchical social structures facilitated the governance that enabled the expansion of commerce, trade and exploration.

The European maritime exploration and scientific discovery we associate with the Age of Discovery and Enlightenment was a period of global colonial expansion with momentous implications for the world. Western Europe was now reaching out from cultures founded in the Mediterranean to those of, first, the Atlantic Ocean and then the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Diaz, Columbus, Magellan and Cook opened up four new continents to the people of the Old World.

The establishment of regular contact between Europe and the world marked a quantum leap in the globalization of trade and the launch of modern capitalism as Europe increased in global economic and political power through a period known as the Great Divergence. This period was also marked by major advances in technology, transport, and communication systems. Increase in connectivity and social complexity based on the more efficient use of energy resulted in growth of many kinds that placed increasing demands on the global environment.

The former trickle of food plants and animals between nations now gathered momentum in a major phase of biological globalization that included pests, diseases, pathogens and invasive organisms. This occurred first as a ‘Columbian Exchange’ between the Old and New worlds, later spreading to the Pacific. Scientifically the maritime charting that was completed during this maritime phase of history would establish the boundaries of the world’s major landmasses thus delimiting the regions of future biological inventory. Charts of the world’s coastlines also opened up the world to a subsequent phase of colonial inland penetration.

For about 200 years Europeans skirted the Australian continent making tentative observations and landings as two vastly different cultures confronted one-another for the first time.

Gentlemanly Europe took pride in displaying the animal and plant trophies in cabinets full of stuffed and pressed treasures from the Age of Discovery and all enjoyed the beauty and scientific wonder of the world’s flora more than has ever been the case before or since (see Botanophilia).

Cook’s voyages enabled the later English-speaking occupation of Australia, New Zealand and islands of strategic importance. Britain had the history of social organisation that had made possible the technologies needed for such voyages to take place. Modern technology could however be over-rated. Cook noticed what astounding feats had been achieved with the boats and maritime knowledge of the Polynesian navigators who used comparatively fragile craft monoeuvered using a knowledge of the stars, currents, flight of birds, also the weather, wind,and wave action related to islands. All this contrasting with the massive European galleons navigating by means of the compass, chronometer and sextant (and its precursors the quadrant and octant) whose construction and application required delicate engineering and mathematics.

The long history of developments in social organization emanating from the Mesopotamian core had culminated in the world’s most sophisticated shipbuilding, navigation, and cartography, though Chinese shipbuildng and technology of the 15th century far exceeded that in the West at this time.

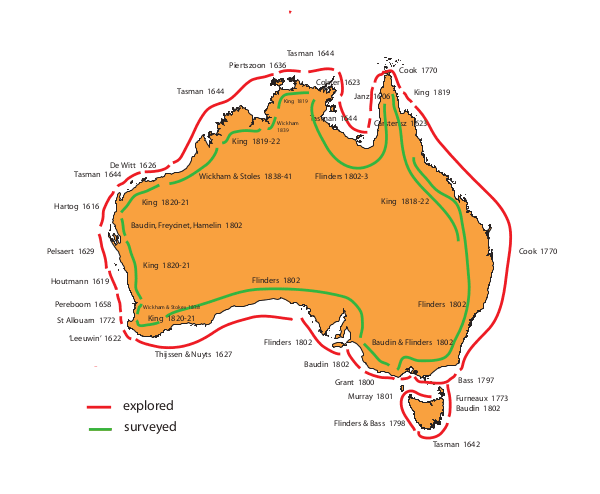

The map opening this article indicates the gradual maritime encirclement and subsequent Europeanization of the continent of Australia. The first glimpses of the Portuguese and Spanish before a more close inspection by the Dutch, especially those visiting or cast onto the west coast. And finally the circumnavigation and charting of the entire coast during settlement. This is a reminder of how easily Australian settlement could have followed a different path, to be dominated by people from Asia or one of several European countries.

For Europeans Australian settlement occurred during the Enlightenment, an exciting and optimistic period where reason and science were a social beacon and scientific discovery of the world’s biota and minerals was at its height as natural history specimens poured into Europe. This was also at the height of botanophilia.

In many ways this was a prelude to the expression of the most powerful biological idea yet known – Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution whose evidential base grew out of cogitations and observations made during his five year voyage on HMS Beagle. It is a great pity that Banks did not live to witness the publication of Darwin’s biological insight as an extended argument for evolution in the ‘Origin of Species . . .’ (1859). This remarkable book produced an explanation for the origin of the vast diversity of organic nature revealed to European eyes during the scientific voyages of exploration that started in earnest with Cook and Banks in 1769 and concluded with his own voyage in the Beagle in 1836. In many ways ‘Origin of Species . . .’ was the Enlightenment ideal of humanism, logic, science, and progress coming to fruition before science entered a new phase as patronage was reduced and science was pursued more by trained scientists and government institutions than wealthy dilettantes and scientific knowledge passed from its European homeland into the territories that it had opened up.

By the middle of the 19th century all of the world’s major land masses, and most of the minor ones, had been discovered by Europeans and their coastlines charted.[7] This marked the end of this phase of science as the “Challenger” expedition of 1872–1876 began exploring the deep seas beyond a depth of 20 or 30 meters. In spite of the growing community of scientists, for nearly 200 years science had been the preserve of wealthy amateurs, educated middle classes and clerics.[5] At the start of the 18th century most voyages were mostly privately organized and financed but by the second half of the century these scientific expeditions, like Cook’s three Pacific voyages under the auspices of the British Admiralty, were instigated by government.[6] In the late 19th century, when this phase of science was drawing to a close, it became possible to earn a living as a professional scientist although photography was beginning to replace the illustrators. The exploratory sailing ship had gradually evolved into the modern research vessels.

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . 22 July 2023 – minor edit

Venus Bay, Victoria, Australia

Venus Bay was named by a French maritime expedition led by Nicholas Baudin: apparently commemorating George Bass‘s trading ship the Venus. Baudin had traded with Bass in Sydney around 1801.

Image – Roger Spencer – 22 May 2021