Ferdinand von Mueller

Between 1880 and 1890

National Library of Norway under the URN no-nb_nansen_147

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Johnstone O’Shannessey & Co. – Accessed 26 May 2021

The introductory article Plant People sets the scene for the selection of plant people described in this series of articles, placing them within a global and plant science context. For a more extended discussion of changes in the form and context of plant study over time see the history of plant science.

This article focuses on a uniquely Australian botanical celebrity.

From the early days of settlement horticulture was a popular pastime in Australia and associations were soon formed, mostly as extensions to agricultural and pastoral societies. In New South Wales there was the Agricultural and Horticultural Society (est. 1826) and in Tasmania there were horticultural societies in Launceston (est. 1838) and Hobart (est. 1839). These societies were of two kinds based on British precedents – those for ‘. . . gentlemen of wealth and standing’ modelled on the (Royal) Horticultural Society of London (est. 1804), and those ‘. . . based on gardeners’ mutual improvement societies of the 1830s’[18]. A related institution, the Mechanics Institute, was first introduced in Britain by wealthy industrialists in the early 1820s for the general moral improvement and education (they had lectures, maintained libraries etc.) of the working man – a foil to the prevalent gambling and drinking – soon arrived in Australia and flourished from the 1870s to the 1920s.

The Victorian Horticultural Society (granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria in 1885) was inaugurated in 1848 by John Pascoe Fawkner at a meeting convened in the Queen’s Head Hotel in Melbourne.[19] Superintendent Charles La Trobe was elected Patron and Mayor Henry Moor elected President.

The British Government granted Victoria independence from the Colony of New South Wales in 1851, and self-government in 1855 and the new colony had soon established its own learned institutions – a university in 1853 (opened in 1855), public library and museum in 1854, a philosophical institute in 1855, and an art gallery in 1861.

After arriving in South Australia in 1847 Mueller was appointed Government Botanist of Victoria in 1853, a post he held for 43 years. Mueller’s botanical expertise and enthusiasm were beyond doubt so, four years after his appointment as Government Botanist and 11 years after the foundation of the Melbourne Botanic Gardens he was, in 1857, appointed director, a post he would hold for 16 years until his style of management eventually proved unacceptable to Victoria’s public and its administrators.

Arrival in South Australia

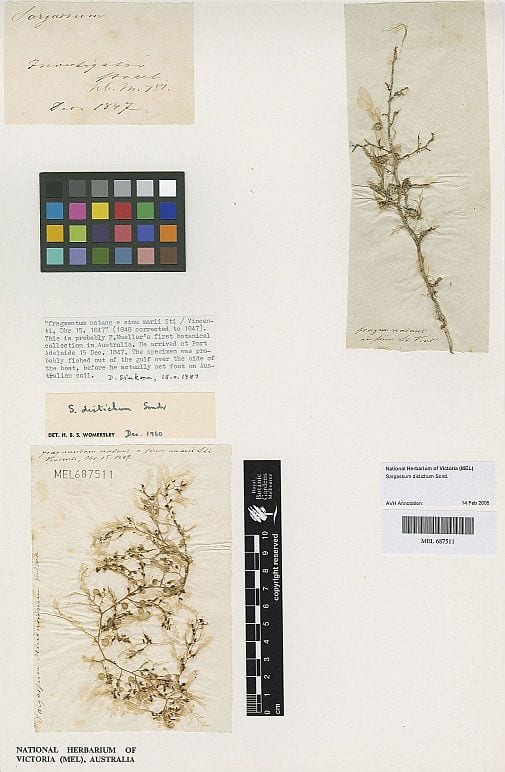

Mueller, who was born in Rostock, Germany, arrived in South Australia on 15 December 1847 when he was just 22 after studying pharmacy and completing a doctorate in botany at the German University of Kiel surveying the flora of southern Schleswig. A measure of his botanical zeal and obsession can be gauged from his first botanical collection held in the National Herbarium of Victoria – a Sargassum seaweed collected in December 1847, its locality written on the herbarium specimen label as ‘Investigator Strait’, presumably plucked out of the sea before he had set foot on Australian soil.

In South Australia Mueller purchased land in the Adelaide Hills, joining the German community and working as a pharmacist. In 1849 he became a British citizen, changing his name from Müller to Mueller, and was familiarizing himself with the vegetation in South Australia, the Flinders Ranges, Lake Torrens and the southeast of the colony he would get to know better than anyone else. With influential scientific friends in Europe and a commendation from William Hooker at Kew he was an obvious choice, in 1853, for the post of first Government Botanist in Victoria, a position he held for 43 years.

Sargassum Seaweed – Sargassum distichum

Collected at Port Adelaide, presumably before Mueller had stepped off the boat when first arriving in Australia on 15 December 1847

Courtesy National Herbarium of Victoria

Discovering & documenting the Australian flora

With no resident botanists, facilities, equipment or books Mueller immediately set about accumulating a reference herbarium and library to overcome the frustrating dependence on distant European expertise. He was to almost single-handedly transform the face of Australian botany while significantly contributing to the political and civic life of the expanding colony. In many ways he took over where Banks had left off demonstrating a keen eye for plants of value to commerce and industry and a doggedly single-minded scientific desire to complete an inventory of the plants of the entire continent for which he would harness a vast network of collectors including explorers, miners, pastoralists, clergymen, teachers, surveyors, and amateur naturalists.

In Victoria Mueller’s first task was to familiarize himself with the land under his charge making two collecting trips that were to set the pattern for the future. After about six weeks in his new position he set off alone with a pack horse occasionally using Aboriginal assistance and accepting settler hospitality for three-months visiting the alpine region of Mounts Buffalo and Buller, then to the sources of the Latrobe River and on to Wilson’s Promontory before returning to Melbourne. This trip was followed immediately by a more ambitious trek of about 2,500 miles starting in Nov. 1853 lasting five and a half months, this time to the west including the Grampians, Avoca River, through the mallee to Swan Hill, along the Murray to Omeo and the Cobberas, down the Snowy to Gippsland and back to Melbourne. The two trips covered about 4,000 miles through the state’s major vegetation types and accumulated about 1,500 new plants, all needing description and classification a task that he tackled with undaunted efficiency. Many of his early specimens were sent to Garmany and described in the journal Linnaea under the heading Plantae Muellerianae.

He was an avid supporter of inland expeditions and from 1855 to 1856 he joined Augustus Gregory’s expedition to North Australia, the party travelling from Victoria River on the northwest coast of WA to Moreton Bay on the east coast on the way collecting around Sydney, Brisbane and Cape York, overall accumulating about 800 plants new to science.

Director Melbourne Botanic Garden

Excursions were curtailed in August 1857 when Mueller was appointed Director of Melbourne Botanic Gardens. We are given a full insight into Mueller’s vision for his gardens at the very end of his time in charge.

Two years before Mueller was removed from the office of gardens’ director he delivered a lecture at Melbourne’s Industrial and Technological Museum (a precursor to the Museum of Victoria) on 23 November 1871 in which he set out what he considered to be the broad functions of a botanic garden. These functions aligned closely with the goals of other colonial botanic gardens but they were enumerated in extraordinary fine detail using Melbourne Botanic Garden as his example. Though titled The objects of a botanic garden in relation to industries . . ., Mueller broadened his theme of ‘industrial pursuits’ into an overview of the objectives of botanic gardens in general since ‘I found occasion to overstep these precincts, to bring the many other objects of a true botanic garden also, at least briefly, under the view of this audience’.[20]

Mueller’s scientific management of the Gardens was at this time being challenged by those who wanted a more visually pleasing garden landscape. His paper was no doubt in part a response to critics, a thorough exegesis and defence of his views presented like a manifesto. His efforts were to no avail as, in 1873, though retaining the title Government Botanist, he was relieved of the directorship and re-located to his Domain herbarium where he worked until his death in 1896.

The Vision

Mueller’s 37-page ‘brief’ lecture provides a valuable insight into the man himself, his brilliant attentive mind, the depth of his plant knowledge and the rigour of 19th century scholarship, all expressed through the circumstances and objectives of a colonial botanic garden. Like other academics and administrators of his day he showed extraordinary dedication to duty and obsessive work habits leading to with a prodigious output – around 6000 letters a year and a career total of over 1500 publications.[21

As an impassioned botanical advocate his thoughts tumble onto the page in a torrent, his busy brain exploring all aspects of the relation between plants and people – from fashionable ferns to the public funding of botanic gardens. He builds to a crescendo of sentiment, praising nature and reminding his audience of their mortality by noting that the cycles of nature are ‘. . . a symbol of an imperishable existence and of an eternity beyond this world’ before concluding with words from German Romantic poet Friedrich Schiller. This is the tirade of a fanatical plant preacher delivering a botanical sermon that would have driven both himself and his audience, if not to distraction, then certainly to exhaustion. But he never shies away from the enormity of his task, stating clearly how he believes botanic gardens are the appropriate institutions to examine the place of plants in both nature and culture.

The Objects, for all its flamboyant extravagance, must rank among the most astute and in-depth critiques of the notion of a botanic garden that have ever been written. It therefore warrants quoting at some length because it invites us to not only place ourselves in Mueller’s historical shoes, but to rethink the role of botanic gardens in our own times. By articulating his vision so clearly (nothing written by his Melbourne predecessors was remotely equivalent) he facilitated future comparisons between ‘then’ and ‘now’ in the constant re-evaluation of the aims and objectives of botanic gardens.

The Objects . . .

Mueller’s account begins by asking the extent to which botanic gardens can ‘. . . exercise a vivid and powerful influence on education, on technology, on rural pursuits, and on the advancement of independent researches for the enlargement of phytologic knowledge’ (. . . Objects . . . , p. 151). He then provides an intentional definition that distinguishes botanic gardens from other kinds of garden by their programs of science and education:

‘. . . the true botanic gardens of this age [are] scientific gardens; while all those institutions, in which no real phytologic researches are carried out, or in which the main aim does not consist in affording instruction, might well be called public pleasure gardens, or perhaps recreation grounds or parks, according to the design for which they are created, or in consonance with the requirements for which they are maintained (p. 152).

The early origins of botanic gardens he places firmly in ancient history, well before the medicinal gardens of early modern Renaissance Italy, noting that the gardens of his times were much more than mere medicinal gardens. Botanical science, he claims, began with the ancient Greeks and the special contribution of Theophrastus and his garden (370-288 BCE).

‘. . . from the early transcendental days of Greece up to the most recent decennia all institutions designated as botanic gardens were mainly or exclusively devoted to the rearing of such plants as were adopted for medicine, for alimentary or industrial purposes; and it would be little short of relapsing into barbarism, were we to alienate any such institutions of ours entirely from their legitimate purpose’ (p. 155).

He refers to early precursor medicinal gardens of the Italian Renaissance when monastery-style physic gardens opened to the public . . . that ‘In 1333, the botanic garden of Venice was established as an institution accessible to the public’ ( p. 154). We also know, for example, of similar medicinal gardens in Italy like that at Salerno established by Matthaew Sylvaticus in the south (founded ?1309), and the Vatican physic garden (1447). In Germany there was the municipal apothekengarten of Hamburg est. 1316, No doubt there were others. All recalled the earlier monastic physic gardens.

Today it is Pisa (founded in 1544) that is frequently cited as the first modern botanic garden, probably because at this garden there was the first appointment of a chair of botany in an act that symbolically distinguished a new scientific discipline, botany, as being distinct from medicine.

After a brief outline of some of the major contemporary botanic gardens of his day he concludes this section with a note of deference:

’. . . among all existing state gardens none can be compared to the grand and justly-famed establishment of Kew.’

Then, with gusto, he elaborates on his main theme:

‘As an universal rule, it is primarily the aim of such an institution to bring together with its available means the greatest possible number of select plants from all the different parts of the globe; and this is done to utilise them for easy public inspection, to arrange them in their impressive living forms, for systematic, geographic, medical, technical or economic information, and to render them extensively accessible for original observations and careful records. By these means, not only the knowledge of plants in all its branches is to be advanced through local independent researches, conducted in a real spirit of science, but also phytologic instruction is to be diffused to the widest extent; while simultaneously, by the introduction of novel utilitarian species, local industries are to be extended, or new resources to be originated, and, further, it is an aim to excite thereby a due interest in the general study and ample utilisation of any living forms of vegetation, or of important substances derived therefrom. All other objects are secondary, or the institution ceases to be a real garden of science. But the detailed interpretation of these fundamental rules may be more or less rigorous, as the extent of the operations thus designed must very largely depend on the natural facilities and monetary means which are at command for the purpose (p. 156).

He then looks to the specific colonial problems of settlement, future developments and aesthetic considerations:

‘Moreover, the early attainment of any of these varied objects must evidently be all the more difficult in a new country, where in the first generation we are passing yet through the laborious and expensive process of founding all those institutions, from which in the natural course of events a later time can only derive the fullest benefit. But in all these planting operations indicated for scientific demonstration we can still find full scope for the display of tasteful ornamentation and picturesque grandeur’.

This is followed by his account of some of the many meanings for the expression ‘plant diversity’ – from global ecology to individual variability, while also alluding to additional comparative ecological, geographic, aesthetic, social and even religious considerations . . . and all related to Melbourne’s unique climatic conditions:

‘A real botanic garden, then, ought to display the living vegetation in its multifarious forms as far as ever local circumstances will permit. All the plants of the globe build up together a great harmonious system in nature; they are all referable to distinct specific forms, all created by design of an Almighty power for special purposes; they are, moreover, all endowed with well-defined qualities, all interesting and beautiful in themselves, and eligible for our varied wants. We may accumulate collections still more extensive for our phytologic museums than for our garden displays; but we still need to study, as far as we can, the forms of the vegetable empire in their living freshness, their natural grace and vital beauty. What can be more instructive than to compare allied species, from often widely distant parts of the globe, when placed in culture side by side . . . To accomplish great results in all these respects we have in our climatic zone enviable facilities; and thus horticultural pursuits for strictly scientific purposes become also here far more grateful than in the countries of colder climates where most of us spent our youth. . . . how we can rear here without protection the marvellously rich and varied vegetation of South Africa; how in our isothermal zone we can bring together the plants of California, New Mexico, Florida and other southern states of the American union, and how we need no conservatories for most of the plants of Chili, the Argentine State and South Brazil. In Australia we require hardly to allude to the singularly peculiar vegetation of New Zealand, or the gay, curious and remarkably varied vegetation of West Australia, because We are rightly accustomed to regard these neighbouring colonies as portions of the great integral southern empire of Britain; but it requires to have studied the vegetation of Australia and New Zealand specially to appreciate its richness, and to understand fully its value for a garden in a colony like Victoria (pp. 156-157).

Mueller’s colourful German-English prose makes point after point, each as direct and pertinent today as it was when written down 150 years ago.

There follows a discussion of different plants and their possible utility when cultivated in Melbourne, following the theme of colonial botanic gardens as experimental stations. The article is rich in factual detail and deserves reading in full, but the following collection of snippets catches the flavour of his creative imagination:

‘Test experiments, initiated from a botanic garden, might teach us whether the Silk Mulberry tree can be successfully reared in the Murray desert, to supplant the Mallee-scrub . . .’.

Which oaks are ‘. . . eligible for avenues’ or as ’. . . timber trees’. ‘. . . from a single imported Asiatic Ash 15,000 young trees were obtained by me for Victoria’. ‘. . .how many of the 160 true species of Willows and of their numerous hybrids are available for wickerwork; and we should learn, whether any of the American, the Himalayan or the Japan Osiers are in some respect superior to those in general use’. Which trees ‘. . . can be adopted as a forest tree for this colony’ . . . ‘. . . how far Californian Red-wood trees (Sequoia gigantea), or New Zealand Totaras, may give us good timber, when merely grown from cuttings in the open’. ‘What other utilitarian plants, such as the Fig, various Coniferae, Tanners’ Wattles, grasses, &c., we may gradually establish …’ ‘Numerous Pines and other industrial trees have been secured for this country . . .’. ‘. . . I cannot imagine anything more interesting than a full collection of Acacias . . .’ . . . ‘To me 300 Acacias appear far more valuable than 300 varieties of particular fancy flowers, at least in a young botanic garden, where their names, their native countries, and perhaps even the uses of many could be learnt.’ . . . ‘Good Wattle-bark is three times as rich as Oak-bark in tanning principles, and much quicker produced, and that in localities where no oak will thrive.’ ‘We should watch their growth in various geologic formations; we should note their adaptability to certain climatic regions.’

Mueller is well known for his introduction of blackberries to the Australian bush, his willingness to replace natural vegetation with introduced species contrasting strongly with today’s sensibilities, but reflecting what the establishing colony believed important at the time.

He praises many native plant genera as easy to cultivate and notes the outstanding potential of those from Western Australia, discussing some that would be suitable for conservatories, and how a botanic garden can offer economic, scientific, and horticultural evaluation and sustenance for the human spirit:

‘Such an assemblage affords at all times ample material for original study and designing art, while its contemplation raises the taste and standard of horticulture . . . a botanic institution should aspire to these higher aims. . . . ‘such a collection . . . can also become commercially one of quite a lucrative gain.’

‘. . . simultaneously every one, as a rule, evinces a desire of acquiring some more accurate horticultural information, and of becoming acquainted with some item or the other of knowledge relative to the plants around him. This applies, with equal force, to the native vegetation, by which we are surrounded anywhere.’ ‘In all the changeable events of this versatile life, whether the saddest or most hopeful, we are longing to find in the floral world some emblems for our joyfulness, as well as for our deepest grief.. . . flowers seem identified with all the tender feelings and all the gentle sentiments of mankind.’ ‘One of the great objects, which a scientific garden is to fulfil for whole communities, indeed, consists in elevating the traditionary notions or the simple conceptions of plants to scientific cognisance and the highest educational standard.’

He anticipates today’s (2020) RBGV Vision Statement (‘Life is sustained and enriched by plants’).

‘The very existence of the whole animal creation, indeed of man himself, is dependent on plants.’

He draws attention to the need for infrastructure:

‘For the full utilisation of such collections we need moreover to maintain a laboratory and ateliers of other kinds . . . to fix all observations by lasting records, and render them, by issued volumes or by illustrations of pictorial or plastic art, accessible at all times. No sooner does a seed-grain germinate, than it can be utilised for research.’

A year earlier, in November 1870, Mueller had given a lecture on the use of plants in industry at the new Industrial and Technological Museum (opened Sept. 1870) recommending establishment of a botanical section and emphasising mainly exotic timber and forest products. [22] He had previously contributed to the Paris Exhibition of 1855, the wood exhibits being then forwarded to William Hooker at Kew.[23] In November 1861 Mueller’s plant exhibits were on display at the Exhibition Building before they were shipped to London’s 1862 International Exhibition noting its potential as timber for shipping and railway sleepers.[23] Mueller’s own recently completed Botanical Museum was already bursting with his timber, carpological and herbarium specimens. In 1865 he sent a ‘small collection of colonial woods’ to Dublin’s International Exhibition of Arts and Manufactures before preparing at the Intercolonial Exhibition of Australasia for the international Paris Exhibition of 1867. Then again exhibits were displayed in the Industrial & Technological Museum in 1872-3 prior to London’s 1873 International Exhibition which included phytochemical samples. In spite of his demise as director, Mueller was commissioner and judge at Melbourne’s 1880-81 International Exhibition in the new (completed Oct. 1880) Royal Exhibition Building in Carlton Gardens.[23]

He makes quantitative estimates of plants suitable for cultivation. Should native plants be preferred – and are there any plants that should not be cultivated in botanic gardens?

‘Should we not largely surround ourselves with our own native plants, handsome and instructive as they are. The range of cultivation in our state garden has at times been already extensive. In 1865 seeds were collected of 700 species of trees and shrubs in the garden; seeds also of 170 kinds of grasses, of 1100 herbaceous plants, and of 80 species of ferns.’

‘Should we not be able to show in culture the poisonous herbs, against which the squatter as well as the explorer must guard? . . . ‘Of the 110 Saltbushes of Australia, some are ascertained to be eligible as culinary esculents; the majority of these plants are of high value for sheep-pasture’.

What should be the policy for plant exchange and distribution?

‘The command of large collections of museum plants, commenced by my personal field exertions more than thirty years ago, gave here local advantages for affording also to correspondents in other colonies a fuller insight into the characteristics of the vegetation of their respective localities.’

His report for 1861 alone records that the Gardens sent out 51,920 seed packets, 31,455 plants, and 36,474 cuttings.

He is aware of the scientific and social power of botanical illustration in an era when the technology of printing images was changing rapidly (Fig. 28).

‘I suggested the publication of these illustrations in a weekly journal. . . . Sydney Mail’

. . . with an ulterior object of re-issuing the plates and descriptions in a connected form . . . the first illustrations, to be followed, in regular succession, by others, an electro-plate’

Botanic gardens must provide periodic catalogues of their collections:

‘It is unquestionably of importance to provide in any scientific garden from time to time accurate catalogues of the contents . . .’ ‘by united efforts we could provide for the publication of an universal catalogue in annual editions . . . so all horticultural establishments . . . should enjoy the universal use of the best index which at the time can be compiled’.

On providing scientific inspiration, fostering a love of plants and the role of botanic gardens:

‘I have a vivid remembrance with what an enthusiastic avidity many a student commenced his scientific collection of plants from gatherings in a botanic garden; how he sought for correct appellations, traced the indigenous localities of any species, endeavoured to understand the particular relationship of plants, and commenced to arrange systematically what he had gathered … greeted any rarity or novelty with the outburst of absolute delight’.

. . . ‘Such was the first commencement of the luminous career of some of our great naturalists, and such was also the first origin of some of the most important museums of plants. As means of education the collections of a botanic garden, whether exhibited in their vivid freshness, or stored for preservation and reference, may exercise a vast influence’ . . . ‘even the study of languages and geography, through scientific garden plantations, may be fostered, and this in a manner more pleasing than in most other forms . . .’

Plants pervade all aspects of our lives and botanic gardens reflect the particular needs and interests of the times:

‘ . . . Perhaps even it is not too much to contend, that no observant visitor can pass through a scientific garden, be it ever so often, without taking with him in each instance some new instructive information . . . very few may really have a comprehensive persuasion of that actual relation which exists between botanic inquiry and utilitarian application . . . much more difficult then must be the recognition of all that which is only foreshadowed in a dim future. . . . we cannot cast our views around us without meeting, in every direction, objects derived from vegetation . . . what can more readily lead to new local industries . . . to secure by interchange or otherwise additional treasures for the institution . . . recognising the real value and significance of the riches which in his institution are already accumulated . . . the diffusion of special knowledge in a manner best adapted to the requirements of time and place’

‘When an important plant has once been introduced or tested, a task in which a botanic garden must always take a leading share, then rural enterprise and private capital are expected to advance the cultivation and utilisation of such a plant to commercial dimensions’ . . . ‘The miners, in prospecting through the ranges, might scatter the seeds of berries . . .’ ‘. . . the medicinal Squill on our sea-shores.’ ‘. . . the uses of a botanic garden as a horticultural school’ . . . ‘For toxicologic experiments in a botanic garden the various poison plants become of importance . . .’

Mueller evaluates the colony’s development, the need for increased local expertise and the maturing of scientific institutions:

‘We are no longer in the earliest youth of our colonial existence . . . ‘A central institution for phytologic information requires to be maintained among us somewhere . . .’ ‘ . . . A botanic garden, which cannot afford to maintain at least one collector in the field, must be regarded as a very imperfect . . .’.

He is aware of the vagaries of horticultural fads and fashions and the particular attraction of those coming from European cities. But, while conceding the appeal of horticultural display, he holds firm to his predominantly scientific vision by pointing out costs in both money and labour . . . all for questionable lasting benefit:

‘In some parts of Europe the fashions of horticulture have recently undergone some changes again, so far as to render the growing of flowers in masses, or hands, or decorative figures less predominant, as this extremely artificial culture is giving way largely to the far more natural one of picturesque or scenic grouping. I advisedly do not apply to this system of planting the term ‘subtropical gardening’, which is yet retained in the excellent book published this year by Mr. William Robinson, of Kensington, who has contributed by this and other works (such as the one on the gardens, parks and promenades of Paris) so much to ennoble horticulture to simpler natural grandeur, and lead it to higher scientific tastes.’

‘. . . these various cultural systems might even in some instances and to some extent be advantageously blended; but while they may all be represented in a botanic garden, the formal decorative planting or the cultures for exclusive ornamentation should there at least not prevail, but be made subservient mainly to scientific objects. Much in respect to bedding flowers and other simply decorative planting may be fairly left to the gardens formed for private entertainment and pleasure. . . . I hold, that in a public cultural establishment, even in older countries, its endowments are more legitimately employed by devoting them to produce works of permanency and utility; not however falling into the other extreme of shutting out altogether ornamentation in its less expensive form.’ ‘But incontestably a reaction of public opinion will ere long set in; there will be little or nothing to show for much of the expenditure of years, and a just and resentful censure will sooner or later overtake us.’ ‘ . . . Let us study to embrace all that is attractive in any form, whether native or foreign, into one grand whole of magnificence, without singling out a few transitory plants for almost exclusive culture’.

‘. . . we need not disdain those ornamentation works which serve to embellish still more a stately structure. We can build grottos … raise islands, and convert swamps into lakes … have fountains playing … raise statues … to glorify monumentally what is noble and great…’ ‘But … we should never lose sight of the still higher objects for which a botanic institution is founded; otherwise, while trifling away slender means on perhaps even trivialities, we have failed to afford our early guidance to lasting prosperity or progressive and enduring advancements’

He contemplates the blending of art and science:

‘Though . . . if ever we attempted to restrict an institution of this kind to absolutely utilitarian purposes, we assuredly would find the separation or exclusion of simple means of enjoyment a total impossibility. The avenues, formed of timber trees, as forest representatives from wide distances, will afford to the strolling visitor no less of cool umbrageous expanse than if raised for his recreation only. The colouring changes of the vegetation throughout the seasons, or the varied periodic hues of foliage and blossoms, are assuredly not diminished in their impressiveness because the perhaps tyrannic sway of fashionable predilections, or of tastes subject to endless dispute, are left unobeyed in the exercise of the free judgment of science.’

He draws attention to botanic gardens as experimental sites, especially for economic botany:

‘Test plantations as prominent among the obligations of a scientific garden. Some of the results of my experiments on [fibre] strength were given in the descriptive catalogue of Victorian sendings to the Sydney Exhibition of last year. But such tests must be continued or extended . . .’

‘There ought to be, in a scientific garden, representative plants of any important fibre hitherto drawn into industrial use. So it should be with . . . starch-plants, dye-plants, oil-plants, fodder-plants . . . any species adopted in medicine.’

‘Manures in their varied constitution and application require also experimental tests. Diseases of plants, in their increasing multiplicity, need to be carefully traced and elucidated’

Finally, his spiritual conviction and respect for the wonder of nature is expressed eloquently in lyrical form:

‘The soul, sunk in mournful sadness, will also find yet some consolation in a garden of knowledge, and will feel how the power of a Divine Providence pervades every leaf and flower; or the mind susceptible to the religious teaching of nature will there also recognise how the apparently lifeless root or grain sprout under the spring rays again with hopeful vitality from the cold darkness beneath— a symbol of an imperishable existence and of an eternity beyond this world.’

In his ‘Objects . . .’ of 1871 Mueller had clearly articulated an all-embracing vision for the tasks associated with the role of botanic gardens. There is a historical layering of these goals reflecting the changing history and emphases of botanic gardens themselves which included: a concern for herbs, spices and medicinal plants (following the earliest phase of botanic gardens, the physic gardens or hortus medicus with its apothecaries and simples in the age of herbalism); ornamental novelties (reflecting the 15th to 18th century ages of European discovery and enlightenment that brought back novel, beautiful and curious and new plants from distant lands – also reflecting the Enlightenment botanophilia, the fashionability of plants among the European wealthy; economic botany -that echoed the period of colonial botanic gardens, especially the Jardin du Roi in Paris and the Royal Garden at Kew under the de facto directorship of Joseph Banks who facilitated the development of a network of botanic gardens to process plant economic resources from round the globe, the construction of economic museums displaying dyes, plant craft and products, fibres, textiles and so on); plant taxonomy (the period of the Enlightenment associated with the development of descriptive botany which included plant nomenclature, classification systems, especially the artificial ‘sexual system’ of Linnaeus and the ‘natural systems’ of the de Jussieu family and description of plants from round the world).

Colonial context

Early 19th century botanists like Mueller were aware of the scientific magnificence of Paris’s Jardin des Plantes with its associated Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, but with the acquisition of Linnaeus’s natural history specimens in 1778 and the swelling of the living collections at Chelsea and Kew ‘. . . London had become the botanical centre of the world. Nowhere else was there such an accumulation of foreign plants – dried and living – as well as botanical knowledge.[24] Joseph Banks’s interest in economic botany was taken up by William Hooker and his son Joseph at the Royal Botanic Garden Kew where a Museum of Economic Botany was opened in 1847. This tradition was passed on to Australia where the most impressive extant economic museum today can be visited in the Adelaide Botanic Gardens. Opened in 1881 it dates to Schomburgk’s directorship and is now magnificently restored as the Santos Museum of Economic Botany.

The European population of Australia in 1818 was 25,000, at Federation in 1901 it was 3.7 million. In 2019 it stands at 25.5 million.[25] When Mueller became Director the cultivated part of the RBGV comprised six raw hectares (it is now close to 40 ha) containing around 1600 species of plants (Royal Botanic Gardens 1984). Even with meagre resources, he was determined to develop a botanic garden representing as much as possible of the plant kingdom, in a garden following European botanic garden tradition and demonstrating world class botanical thought. Mueller’s correspondence with Kew was at first with William Hooker (1785-1865; Director from 1841 to 1865) who had expanded Kew’s grounds and included a new herbarium, museum of economic botany, and an impressive array of glasshouses. Son Joseph (1817-1911) was appointed Assistant Director in 1855 and eventually succeeded his father as director in 1865, a position he held until 1885. Though a brilliant plant geographer Joseph is perhaps best known as a friend of Charles Darwin and, in the world of horticulture, as a plant hunter who initiated a passion for rhododendrons, introducing many from India to Kew and writing a popular Himalayan travelogue in 1852.

London’s Great Exhibition in 1851 was a statement of Britain’s economic and technological accomplishments that set an example for many trade exhibitions that would follow. Mueller, like Banks and the Hookers, was keenly aware of the political and economic significance of both plant imports for the new colony and the possibility of yet-to-be-discovered plant resources.

By the 1850s economic expectations had shifted from bonanza plants like sugar and tea to plant products that could be processed by manufacturing and industry – and that included the timber produced by forestry.

Mueller investigated local plants as a source of fibres, dyes, perfumes, oils, timbers and construction materials while at the same time acclimatizing crops and evaluating ornamental plants for the decoration of not only his own systematically arranged garden beds but also Melbourne city and regional Victoria’s avenues, parks and gardens. Thousands of plants were distributed free to local residents in the 1860s.

To assist this work Mueller sought a Museum of Economic Botany, a Botanical Museum or Phytologic Museum as he called it, where he could also keep his herbarium of dried plant specimens. This was finally built in 1859-60. In 1865 he established a phytochemical laboratory ‘in a brick building sited next to a stable’. Here exercised his youthful German training in pharmacy and chemistry employing three fellow German researchers to assist him in the task[26]

To meet the demands of economic botany he mounted exhibitions to educate the public, to publicise the potential commercial applications of plant products and to generally promote his entrepreneurial ideas. His first exhibition was for the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the exhibits being previously displayed in the impressive new Exhibition Building in William Street (Gillbank 2008) but he also provided samples for the 1862 International Exhibition in London and the 1866-7 Intercolonial Exhibition of Australasia of 1866. Small exhibitions had also been hosted in Melbourne in 1854 and 1861.[27]

The museum exhibits included oils, dyes, tars, wood vinegar, spirits and tannic acids, all from native plants and all displayed in an 1872 exhibition that was subsequently sent to the London Industrial Exhibition (Watson 1999, p. 56). His efforts culminated in preparation for the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889 which was on the site of the earlier Paris Universal Exhibition of 1867. It marked the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille and was a colonial exhibition symbolised by the construction of the Eiffel Tower which was the tallest built structure in the world for 40 years.

Mueller had envisaged a true botanical museum as an educational building that would also contain his herbarium specimens but the plant industrial products from the Phytologic Museum (as he called it) ended up in the Industrial and Technological Museum that opened behind the Swanston Street library in 1870 with a section, on Mueller’s insistence, devoted to botany.[27] Mueller was finally banished to his Domain herbarium in 1873 (built in 1860 and demolished in 1934 to make way for the Shrine of Remembrance).

Mueller showed a special interest, shared by colonial botanic gardens across the world at this time, in forests – both their conservation and exploitation including the investigation of a whole new range of timbers and their products.[23] Prior to European settlement most of Victoria was ‘forested’. By the mid-1840s, only the Mallee, the eastern ranges and parts of Gippsland remained largely unsettled. Even so, widespread clearing did not occur until the gold rushes of the 1850s though much land remained forest. This all changed when large areas of Crown land were made available for selection in the 1860s, 1870s and 1880s[28][29][30] although wholesale clearing did not occur until after the Second WW. Organised forest management came gradually to Australia between 1870 and 1920, the Forests Commission of Victoria formed in 1918. Mueller was a firm advocate of Pinus radiata as a plantation tree and was possibly responsible for its introduction in 1857 while conifers in particular, under Mueller’s influence, became popular street trees between about 1850 and 1870 probably because many impressive new species had been introduced to western horticulture in the previous 50 or so years[33] Conifers were also a feature of botanic gardens, public parks, cemeteries, schools, and experimental forestry plantations, including his own pinetum in the Gardens, with remnants of the original planting remaining on today’s Hopetoun Lawn, and a few others remaining from his old avenues in the Domain (Fig. 30). Conifers were a favourite of Mueller’s as they were of Clement Hodgkinson (1818-1893), Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands and Survey, who was responsible for plantings in Melbourne’s public space.[31][32]

Mueller was instrumental in gathering the plant science infrastructure needed by the new colony including his museum, library, botanic garden and laboratories. Much of the economic botany he set in train would pass on to other institutions, disciplines and government departments – agriculture and agricultural chemistry, industrial technology and plant pathology. This was, in part, a consequence of the 19th century fragmentation of academic disciplines into new specialisations. Formal academic education in plant science at this time was increasingly absorbed by schools and universities. Melbourne University was established by Act of Parliament in 1853 and opened in 1855 with Mueller’s contemporary Frederick McCoy the founding Professor of natural science (appointed in 1854), beginning work on a System Garden in 1856. It would still be some time, though, before academic disciplines were firmly established: the School of Botany in 1880, School of Biology in 1887, and School of Forestry in 1941. Burnley School of Horticulture (now Burnley College, University of Melbourne) was established in 1891 on the site of the (Royal) Horticultural Society of Victoria whose grounds were laid out in 1861.

This was also a time when many colonial botanic gardens served as agricultural research stations.[35] In Melbourne agriculture was largely independent of the RBGV (The Agricultural Society of New South Wales was founded in 1822; the Port Phillip Agricultural Society was formed in 1840 and followed by many local versions in the other settlements.[34] Gradually not only agricultural influence was shed but, more slowly the plant technology, and plant pathology, the passing of functions from the RBGV to other institutions eating into Mueller’s vision of botanic gardens as social centres for his twin pillars of education and science.

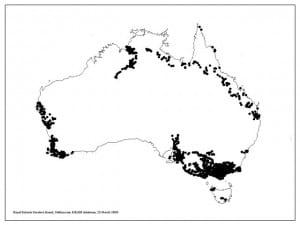

In his role as Government Botanist Mueller concentrated on the taxonomy of the native plants of the entire continent (Fig. 31). Undaunted, this project was completed, as Flora Australiensis, in seven volumes between 1863 and 1878 overseen by the primary author George Bentham based at Kew (Bentham, like Mueller, was also a workaholic. Bentham never visited Australia: Mueller never visited Britain). This inventory of Australian plants was part of a broader descriptive account of plants growing throughout the British Empire, and therefore a major step towards the global flora that is in progress today.

In a remarkable turnaround from the early days of settlement, Melbourne was taking its place on the world stage, enriched by mineral wealth and agriculture. Melbourne had gathered a measure of wealth from the gold rush and the thriving agriculture was providing citizens with regular meat, unlike their fellows in the cities of industrial Britain. Australian native plants, so much a part of botanophilia, had lost their fascination by being so difficult to cultivate. British horticultural fashions and interests had moved elsewhere although Europeans were still enthralled with natural history in general and exotic plants in particular. Colonists, socially isolated from the mother country, hankered after the amenity attractions of new parks so admired in the rejuvenated cities of Europe. The search continued for hardy and attractive street trees. There was now the relief of colourful autumn foliage on deciduous trees, a menagerie (Sydney also boasted a zoo in its gardens from 1862 to 1883), bandstands for brass bands, and gardens perceived more as a pleasant background for the Victorian pursuit of promenading.[36]

One measure of Mueller’s remarkable influence was the presence, in 1872, of more than 20 botanic gardens in the state[37][38][39] although Pascoe[40] now lists 45.

His educational ambitions and achievements are discussed in some detail in Lucas, Maroske & Brown-May[41] and will not be developed here except to point out his obvious determination to serve both the public and science. His passion for plants meant that he would seize every opportunity to promote botany and the gardens, through lectures, articles in journals and newspapers, reports, books, pamphlets, exhibitions and their associated publications, along with a constant stream of scientific papers and a vast correspondence.[21]

Mueller’s mission ranged widely across the nexus humans/plants/science. Clearly, he wanted to be all things to all people, embracing every plant possibility. Several thicker strands emerge from the many threads of his thought. He was deeply concerned with: economic botany; the need to experiment with and explore all possible economic opportunities; a desire to engage with his wider community; to provide public education; carry out independent scientific research; acknowledge the botanical debt to medicine and food plants; empirically test, trial, acclimatise and evaluate plants in many different ways; display plant diversity; emphasise geographic, economic and technological values; maintain records; the choice of plant arrangement being scientific in intent but pleasing to the eye and with restrained decorative display; promotion of botanical institutions; plant trials and experimentation; horticultural evaluation; economic and ecological applications; tree potential for forestry; plant promotion within its full cultural context of plant meaning and symbolism that was so much stronger in those times than it is today; add to the scientific community and its research capacity; encourage plant exchange where beneficial; assess the role of native plants and plants appropriate for the collections.

Taxonomy continues

Exploring continued in 1867, this time in the West, first at Albury, Stirling Ranges and SW WA, and then in 1877 when he was in his 50s, along the Murchison and Gascoyne Rivers inland from Shark Bay. Eventually he disappointed his public who resented plants displayed in a didactic and formal style when the Romantic idiom of more aesthetic display had become so popular in Europe. Replaced in 1873 as Director by landscaper William Guilfoyle he nevertheless retained his title and duties as Government Botanist, working in his herbarium in the nearby Domain but bitterly refusing to ever set foot again in the gardens. Like many of his predecessors he was keen to introduce plants not only to his gardens but also into the bush where it might be useful being one of the possible introducers of the weed menace blackberry. He supplied seed to Giles and to Burke and Wills (not used). Clarke and was a leading light in the Acclimatisation movement.

Herbarium

A first task was the construction of a herbarium building in the King’s Domain near the Shrine of Remembrance where he could house his specimens, a job that was completed in 1861. From 1858 to 1861 his herbarium increased from 45,000 to a capacity of 160,000 specimens. By 1865 the number had risen to 286,000 and in 1868 he estimated that the collection now totalled 350,000,[1] its numbers strengthened by the voluntary collections of pastoralists, miners, clergymen, teachers, surveyors and amateur naturalists, some of whom he had inspired on his trips. This work was crowned by the publication of Plants Indigenous to the Colony of Victoria in 1862 and, in 1863 his announcement that ‘the botanical investigation of the territory of our colony is now nearly completed’. The numbers would continue to climb, reaching 500,000 in 1888, 750,000 in 1891 until by 1894 it was close to a million.[2] His vision for the herbarium was clear, it was to: house a reference collection of specimens and library that would serve as a basis for research and publication; to assist in the development of industry; and be available to the general community.[15]

Supplemented by specimens sent from overseas the herbarium expanded to become the largest in the Southern Hemisphere and remains one of the largest. At its height Mueller considered it among the top nine herbaria of the world, the others being: Berlin, Boston, Florence, Geneva, Kew, Leiden, Paris, and Petersburg.

Flora of Australia

Like the scientists of his day Mueller exchanged numerous letters with his fellows (around 3000 a year for several years) among these being a regular correspondence with the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, William Hooker and William’s successor-son Joseph. Although Mueller had always wanted to write a Flora of Australia this huge task fell to the well-heeled and brilliant George Bentham (1800-1884) chosen by the Hookers of Kew where he had worked daily after donating his private herbarium in 1854. Bentham was a trained lawyer who found botany a lure that was impossible to resist. In 1855 Bentham moved to London and, for the rest of his life, worked at Kew for five days of the week, taking only short summer holidays. Though these achievements alone were monumental his popularity had come through his Handbook of the British Flora of 1858 which he completed in about six years, and the foundational three-volume Genera Plantarum (1862–1883) which was a collaboration with Kew’s director Joseph Hooker. Bentham had access to the early collections made in New Holland and the literature needed for this task was all housed in Europe. This did not deter Mueller who established his own journal Fragmenta phytographiae Australiae ‘to accumulate gradually the literary material for a Universal Flora of Australia’. The seven volume Bentham and Mueller Flora Australiensis was published between 1863 and 1878, taking 15 years to complete, Bentham had started the task when he was over 60 and saw it to completion when he was 78. He never visited Australia. It was the largest flora of its day and, unlike similar works of the day, based on a natural classification. Mueller was a major contributor to the project with first-hand knowledge of the flora and extensive herbarium collections, all of which were sent to England. All-in-all he was a prime example of Victorian industry, writing more than 800 papers or major works on botany.[16]

Bentham shared Mueller’s capacity for dedication and voluminous publication: while working on Flora Australiensis he was President of the Linnean Society from 1861 to 1874 and just before starting work on the Australian flora had published the Flora Hongkongensis in 1861. While working on Australian plants he was also assembling, with Joseph Hooker, an account of the world’s genera of flowering plants Genera Plantarum which was published between 1862 and 1883.[3] With no school or university education he was skilled in many languages and other subjects including law and philosophy – no doubt benefitting from the influence of well-educated relatives like his uncle the reformist philosopher and lawyer Jeremy Bentham. Mueller would have dearly loved to complete the project himself, and he certainly had the botanical expertise, their combined work has been universally admired by taxonomic botanists, not least those tens of botanists contributing to Bentham and Mueller’s update, the current multi-volume Flora of Australia project whose first was published in 1981 and still continues in 2014 with many volumes still to be published.

Dismissal as director

Mueller had ambition beyond any reasonable expectation as he set out to explore an entire continent, discovering and documenting its indigenous flora and, by managing a botanic garden in a young colony, advise and assist in the management of colonial plant resources – their import and export and use – both native and exotic. It was an astounding vision and challenge that, to all intents and purposes, he achieved.

Mueller’s science was impeccable, and his encyclopaedic knowledge of plants placed him in an ideal position to pronounce on plant needs in the blossoming colony. But his diet of science and education was not what the people of Melbourne wanted in their garden. Visiting English novelist Anthony Trollope in 1870 observed that ‘The Gardens at Melbourne are as a long sermon by a great divine, whose theology is unanswerable but his language tedious’ (see Hyams and McQuitty 1969, p. 245) while Crosbie Morrison (1946, p. 26) in a guide book to the RBGV spelled out the disenchantment as follows ‘. . . the gardens became, with humourless teutonic thoroughness, a living text-book of systematic and economic botany, with garden beds for pages’. The Victorian Board of Enquiry Report that led to his dismissal complained of his lack of experience in practical horticulture and the need for . . . art skilfully applied to the embellishment of nature (cited in Pescott 1982, p. 65).

After Mueller

When Mueller departed the scale of herbarium activity was reduced to being a plant identification and information service with special emphasis on weeds. Donations from overseas dropped sharply and native species were mostly supplemented by donations and botanists working in their spare time. In the 1950s, after the two World Wars and Depression, field collection resumed and scientific publication began with the first issue of the eponymous journal Muelleria in 1956. The clear need for a new herbarium was met with the opening of the present herbarium in 1934 marking the centenary of Melbourne. Construction of a circular extension to this building began in 1988 and it was opened in 1989.

The relation between the gardens and other government departments had always created difficulties in devising objectives and budgets. In 1992 a Board of management was appointed under the Royal Botanic Gardens Act of 1991 when the herbarium was designated part of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne (now Victoria) and the specimens and library referred to in combination as the State Botanical Collection. In the same year the recording of all specimens on a computer databse began as MELISR, now (2017) numbering 873,000 entries and ongoing. Staff numbers and activities continued to increase with the employment of a botanical illustrator and more research scientists. Notable projects include the placing of the Flora of Victoria and Horticultural Flora of Southeastern Australia online, the Millennium Seedbank, the Australian Virtual Herbarium (specimen data entries) available online, and the imaging of Type specimens.

The position of Government Botanist has subsequently been held by:

Johann Luehmann (1896-1906)

Alfred Ewart (part time 1906-1921)

William Laidlaw (1924-1925)

Frederick Rae (1926-1941)

Alexander Jessep (1941-1957)

Richard (Dick) Pescott (1957-1970)

James Willis (1970-1971)

David Churchill (1971-1992)

James Ross (1992-2005)

David Cantrill (2006- )

Garden Curators & Directors:

John Arthur (1846-1849)

John Dallachy (1849-1857)

Ferdinand Mueller (1857-1873)

William Guilfoyle (1873-1909)

John Cronin (1909-1923)

William Laidlaw (1923-1925)

Frederick Rae (1926-1941)

Alexander Jessep (1941-1957)

Richard (Dick) Pescott (1957-1970)

David Churchill (1971-1986)

John Taylor (1986-1992)

Philip Moors (1992-2012)

Timothy Entwisle (2013-)

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

Mueller never married and was, by today’s standards, a workaholic, describing more than 2,000 Australian plant species and producing more than 2,000 publications. Many of his articles provided perceptive commentary and insight on matters related to botany and horticulture – such as the role and function of botanic gardens, papers on economic botany, forestry, and even conservation. In 1857 he produced a review of exploration in Australia which followed the theme of geographical research promoted by the popular and influential von Humboldt a fellow Prussian that he admired.[10]

Mueller was conservative, even for his day, regarding Aboriginals as a ‘barbaric people in need of the civilizing influence of Europeans’[4][5][6][7] His desire to modify and improve the environment for human use through acclimatization would alarm today’s botanists. In 1870 at a public lecture at Melbourne’s new Industrial and Technological Museum he had intimated that the ‘400 coniferous trees and 300 sorts of oaks’ could be naturalized in Victoria’s ranges and that ‘of about 10,000 kinds of trees, which probably constitute the forests of the globe, at least 3,000 would live and thrive in these mountains of ours’.[8][9] His habit of spreading blackberry seed while on collecting trips as a future source of food has become legendary.

In 1860 Mueller received a presentation copy of the first edition of Darwin‘s On the Origin … another being sent to Charles Moore at Sydney. Darwin had corresponded with Mueller in 1857 asking about the performance of north European plants in South Australian conditions, Mueller’s reply being lost: Mueller did not reply to a subsequent letter from Darwin in 1858, the year that Darwin had signed Mueller’s nomination for Fellow of the Linnean Society.[13] Darwin also canvassed and received Mueller’s assistance concerning Aboriginal facial expressions while rsearching for his ‘The expression of emotion‘. Like the other eminent natural historians of his day, Frederick McCoy and William MacLeay, Mueller remained a theist, misunderstanding key aspects of Darwin’s theory. He accepted that natural selection could operate within a species but not sufficiently to produce speciation saying that he must ‘oppose with sadness‘ the theories of Darwin and in one of his few recorded statements on the matter regarding atheism as a threat to social order.[14] In the face of Mueller’s momentous contribution to the botany of a continent entirely new to Europeans it has been pointed out that his attention was focussed unswervingly on descriptive botany, and that he made a limited contribution to theoretical and experimental botany.[14]

The exploration was to continue throughout his life, both within and outside Victoria. In 1880 he told French botanist Alphonse DeCandolle he had ‘travelled on horseback and on foot 28,000 English miles [45,062 km]!’, a figure he repeated elsewhere[11] – this was in all states and through the continent’s major vegetation types, possibly a greater distance, and certainly more varied, than any other explorer in Australian history including Leichhardt, and a feat that will never be repeated.

Much of his time was spent battling government bureaucracy and, as an eccentric, he was mercilessly lampooned by both the public and press for his ever-present scarf (he had a dread of tuberculosis), love of meringues, and a steady flow of English neologisms spoken in a rich German accent.

Mueller was profusely decorated, becoming a baron when the King of Wurttemberg added the ‘von’ to his name in 1871 and being awarded a KCMG (knighthood) the from the British Crown. He was always a prominent and contributing figure in both academic and public life. With a well-established international reputation he was, without doubt, Australia’s most outstanding botanist and arguably Australia’s greatest ever scientist.

Timeline

1847 – Arrives in South Australia aged 22

1853 – Appointed first Government Botanist of Victoria in January. Travels on horseback for three months to the alpine region of Mounts Buffalo and Buller, then to the sources of the Latrobe River and on to Wilson’s Promontory, then in November for five and a half months to the Grampians, Avoca River, through the mallee to Swan Hill, along the Murray to Omeo and the Cobberas, then down the Snowy to Gippsland collecting about 1500 plants new to science and travelling about 4000 miles

1855-1856 – Augustus Gregory Expedition to North Australia from Victoria River on the northwest coast of WA to Moreton Bay on the east coast collecting about 800 undescribed species

1857 – Appointed Director of Melbourne Botanic Gardens his emphasis on plant classification, order beds, and economic botany for the colony, distributing plants from the gardens around the state; explores the Otways

1860 – Returns to unexplored parts of the alps, then on to eastern Victoria and adjacent New South Wales

1861 – First Herbarium building erected in King’s Domain, remaining until 1934 when the current National Herbarium of Victoria was built

1862 – Publishes Plants Indigenous to the Colony of Victoria

1867 – Explores Albury in Victoria then to the Stirling Ranges and Southwest Western Australia along the Murchison and Gascoyne Rivers inland from Shark Bay

1873 – Replaced as Director of the Botanic Gardens by William Guilfoyle but retains his position as Government Botanist moving into his herbarium in the Domain

Key points

- He was the first Government Botanist of Victoria and the first Director of Melbourne’s Botanic Gardens (though not its first Curator)

- Australia’s first significant resident botanist and a leading Australian scientist at least of the nineteenth century and arguably of all time

- A prolific author with a vast correspondence, producing more than 2,000 publications and describing more than 2,000 new plant species, mostly Australian but also from New Zealand Papua New Guinea and Pacific islands, usually in his own journal the Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae and as co-author with London’s George Bentham of the monumental Flora Australiensis (1863-1878)

- As an explorer over the years he travelled on horseback possibly more than any other explorer of the Australian continent covering more than an estimated 45,000 km

- He played a leading role in the scientific institutions and societies of his day

- By 1868 he estimates his plant collections, supplemented by those acquired by others, amounts to about 350,000 herbarium sheets, in 1891 about 750,000 and by 1894 close to a million

- (1863-1878) was the largest Flora of the day and one of several which in combination constituted a Flora of the British empire

- He wrote more than 800 papers or major works on botany

Media Gallery

State of the Ark: What is an Herbarium?

Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria – 2017 – 1:29

State of the Ark: That’s a Wrap

Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria – 2017 – 0:58

State of the Ark: Library Adventures

Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria – 2017 – 3:10

Five Questions with Tricia Stewart

Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria – 2020 – 10:24

State of the Ark: Specimen Inspection

Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria – 2017 – 1:28

Explore the Weird and Wonderful Garden at Cranbourne Gardens

Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria – 2020 – 2:43

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . substantial revision 14 October 2020