Roman Britain

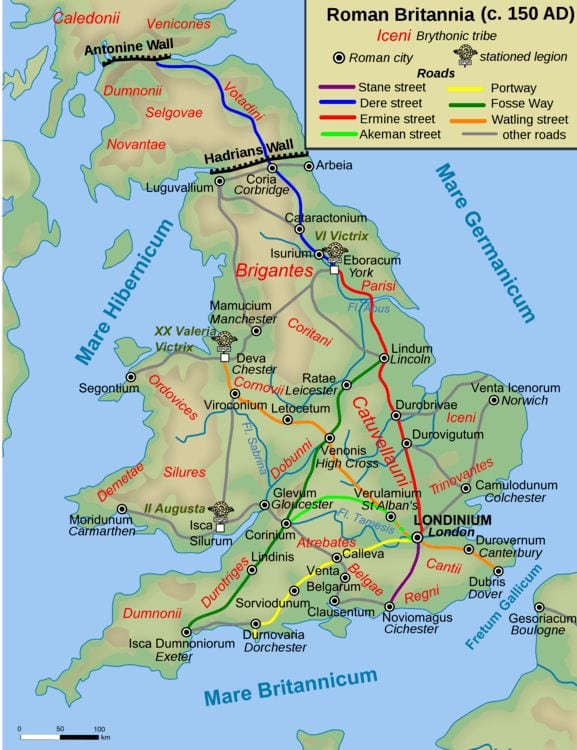

Celtic tribes, Roman settlements, and main roads in Roman Britain c. 150 CE

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

This web site examines the history of ancient Rome from three perspectives: the invasion and occupation of Britain and its implications for the subsequent British Empire and Neoeuropes; the Roman relationship to plants; and what the Roman Empire can teach us about sustainability. For a more contextual account of Romon Britain see Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Introduction – Roman Britain

Roman civilization incorporated much of the Mediterranean culture that preceded it, including the technological and other developments that had occurred in the Fertile Crescent, and the intellectual sophistication of ancient Greece.

As Roman armies spread across Europe, so too would their tradition of imperial administration, culture, trade, law, and local governance, including the artistic use of monumental architecture, elaborate public and private parks and gardens, and avenues of street trees.

Much later, after a European Renaissance that recaptured the spirit of these classical times and an Enlightenment built on humanism, reason, and science, this legacy of Western antiquity was passed on to the world through the European colonial empires, the Neo-Europes of the 18th and 19th centuries, most notably the British Empire that flourished during Victoria’s reign from 1837 to 1901.

It was the Roman period of history, itself derived from the Mesopotamian core, that would establish the general tenor of Western existence . . . including traditions adopted in food, forestry, agriculture. and gardens.

These aspects of Roman life did not develop in isolation so, the Roman Empire must first be set in context before then considering the British manifestation that was passed on to the world through the British Empire.

Mediterranean civilizations

The mythological foundation of Rome by twin brothers Romulus and Remus (dated to 753 BCE) was preceded by the Etruscan civilization of central Italy, a vibrant trading culture in a region rich in copper, tin and iron, and possibly of Greek and eastern Mediterranean origin.

The Etruscan civilization reached its zenith in about 550 BCE when it consisted of 12 city-states with Rome at its urban centre, already displaying monumental architecture, aqueducts, and sewerage engineering. There was sophisticated metalwork in gold and iron and a well-developed sculpture and art that was taken up by the later Romans after an amalgamation with the Roman Republic in the late 4th century BCE. Little written record remains of the Etruscan culture.

Apart from the Etruscan heritage and a profound respect for Greek culture, Roman cultural accretions came from the Greek civilizations of the Aegean including Minoan Crete and Thera, the Mycenean, Classical and Hellenistic cultures with their later admixture of Persian elements from the east, all superimposed on the mix of ideas that had been absorbed from the former magnificence and grandeur of the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean.

Roman history

We know about Rome and its empire mainly from Roman literature of the late Republic and early Empire. This was a highly developed literature that followed 400 years after the great literary tradition of the ancient Greeks.

Rome was at first a humble coastal trading centre close to the port of Ostia before it became a city-state that would expand into an empire that spanned half the world. Though Rome itself, as the largest city in the world at this time, was a symbol of industry and commerce, most Romans celebrated their humble origins as farmers on the land. The rich and powerful owned large estates where they built villa retreats that offered respite from city duties.

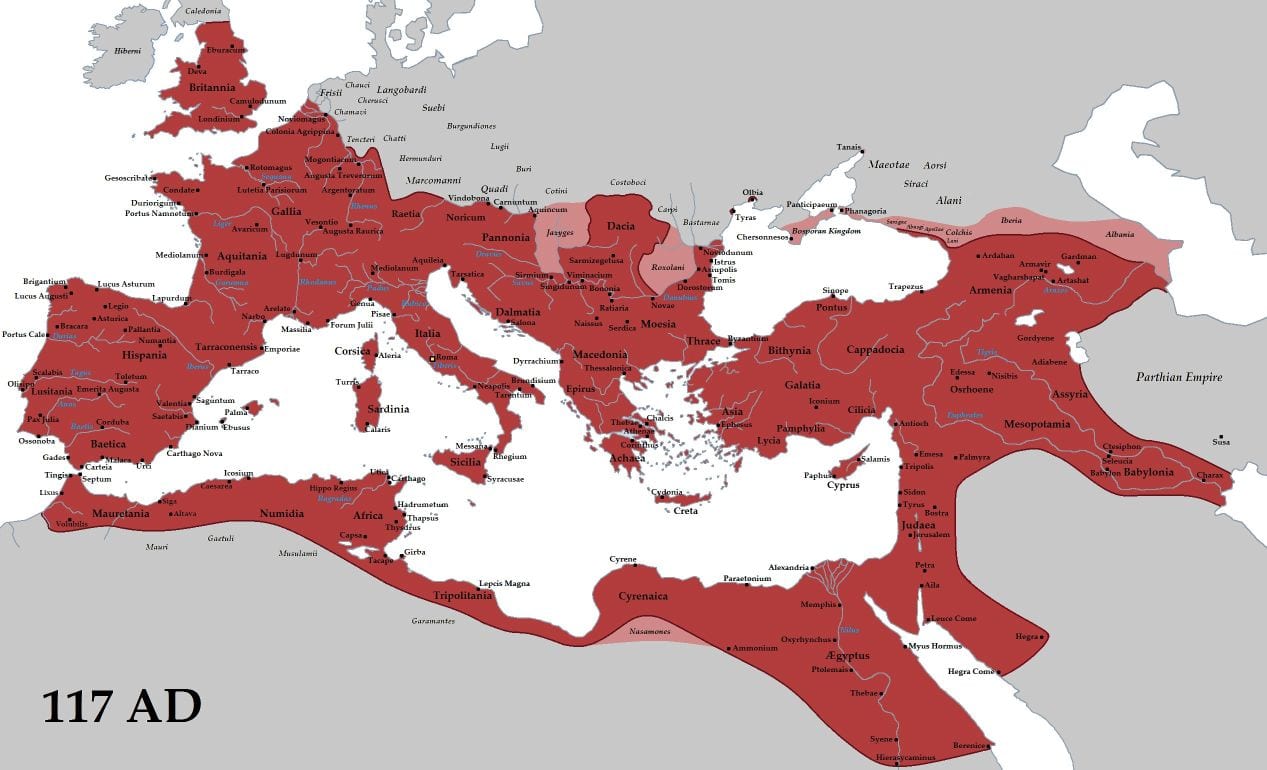

The period of Roman rule, beyond the bounds of Italy itself, is divided into two phases, the Republican period up to the time of Emperor Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) and the subsequent Imperial phase[19] which lasted until about 500 CE (in the West), reaching its greatest extent in about 117 CE. Through the eighth to seventh centuries BCE settlements on the ‘seven hills’ of Rome coalesced to form the city of Rome with settlement reaching into the surrounding district of Latium. Roman mythology tells of two brothers, Romulus and Remus, who fought over which hill should be chosen for the foundation of a new city. Romulus favoured the Palatine Hill and Remus the Aventine Hill. Remus was killed and Romulus founded the city in 753 BCE on the Palatine Hill, appointing himself as its first king and naming it Rome, after himself. There then followed the reigns of seven kings until 509 BCE when popular fear of tyranny led to the establishment of the Roman Republic. Notable among the kings was Tarquin the Elder (616-579 BCE) who constructed stone buildings beginning with a temple to Jupiter, he drained lowland swamps installing a vast city sewer, the cloaca maxima, and also built a city wall and the circus maximus, a large stadium for chariot racing.

At the foot of Capitol Hill with its shrine to the god Jupiter was the city square or Forum Romanum. In this layout Rome was similar to other Mediterranean city states of the day, like Athens with its Agora (market-place) at the foot of the hill called the Acropolis and temple dedicated to the city goddess Athena. During the Golden Age of Athens c. 500 to 300 BCE Rome had been the dominant city of central Italy, trade passing down the river Tiber until, c. 50 CE, the coastal port of Ostia was built by Emperor Claudius.

Rome reached its height under its first Emperor, Augustus in 31 BCE when it was the world’s largest ancient city of 1 million people and a masterpiece of civic organization, the population remaining at about this number for about 300-400 years. It was a city with 5-storey apartment blocks and gravity-fed fresh-water aqueducts extending for 45 miles, that eventually fell into disrepair in about 500 CE. It had taken 1800 years for the transition from village to mega-city.

Under Augustus there were 7000 firemen (vigils) and 20,000 police. Ostia was the main harbor but the artificial Portus was enlarged by Claudius and Trajan. A great sewer or drain, the cloaca maxima, still holds firm in places. London was the first city to reach these numbers in the modern era. As in Greece political conflict arose as conflict between noble aristocratic patrician families interspersed with plebein uprisings. For a while military activity was focused on the Etruscans to the north but in 387 BCE Gallic Celts sacked and burned the city, prompting the construction of an 11 km long fortified Servian Wall that enclosed an area of about 426 ha. Streets of the city were arranged haphazardly and from its dense city centre roads radiated like spokes in a wheel. It was at about this time that the market was removed from the forum which now became an administrative centre replete with temples and basilicas.

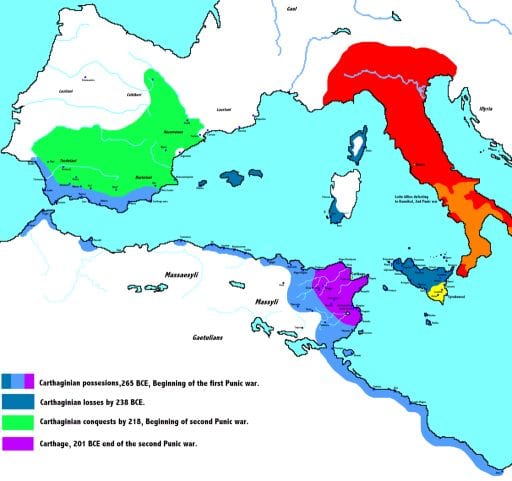

Carthaginian Empire

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Punic wars

Carthage was the Phoenician capital on the North African coast opposite the ‘boot’ of Italy. It was a major Mediterranean trading centre when the Carthaginian empire, at its height during the first millennium BCE, included much of the Mediterranean coast. The Phoenicians had sailed down the West African coast as far as Cameroon and had settled the Balearic Islands, also traded in Iberia and the Bay of Biscay. A clash with Rome was inevitable.

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage (today’s Tunis) from 264 to 146 BCE. From about 900 BCE Phoenician maritime traders had controlled the sea lanes of the western Mediterranean also commandeering a large part of Sicily. Republican Rome was expanding fast and building up its navy. After 100 years of warfare with the Phoeniceans and Macedonians Rome emerged as the dominant Mediterranean power, both east and west, retaining its control until the 5th century CE. Carthaginian General Hannibal during the Second Punic War of 218-201 BCE in 16 days had crossed the Alps that ran across the north of Italy with a team of elephants and 50,000 men to defeat the Roman army convincingly in several battles but failing to achieve conclusive domination. The war was fought simultaneously in Italy, Hispania, and Sicily as well as Macedonia. Seeking revenge the Roman General Scipio Africanus in 202 BCE demolished the Carthaginian fleet at the Battle of Zama, burning the entire fleet in sight of Carthage itself. With the defeat of Carthage in 146 BCE by Tiberius Graccas the Mediterranean became ‘Mare Nostrum’ (Our Sea) and Carthage converted into a major African city of the Roman Empire.

Latium was a city-state (like the Athenian Attica) dominated by an aristocratic class whose military had, by 270 BCE, subjugated southern Italy and, by the first century BCE, extended Roman influence across the Mediterranean, setting up provinces in Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia (227 BCE), Spain (197 BCE), Macedonia and Greece (148-146 BCE), Asia Minor (129 BCE), and Egypt (30 BCE). By the end of the Republican period in 30 BCE Rome’s population was close to 1 million people, a total that would not be exceeded anywhere in the world until the London of Victorian England.

From 27 BCE to 14 CE Augustus, the first Emperor, launched military campaigns into northern Europe with the empire now extending from the Rhine and Danube to the Euphrates, later extending even further to Britain and elsewhere creating the largest empire the world had seen to that time.

British landscape

By the end of the prehistoric period, before the arrival of the Roman armies, most of England’s land had been cleared and exploited: the primeval forests were gone and the area of forested land was, in all probability, less than it is today. Subsequent change was superimposed on this already large human footprint as, during the Bronze Age, the population steadily grew.[12]

Roman Warm Period

Roman occupation of north-western Europe corresponded with a dry era, the Roman Warm Period (Roman Climatic Optimum) which lasted from about 300 BCE to 300 CE with hot, dry summers and winter rain (grapes were grown in southern Britain) as intensive Roman production systems replaced Celtic multiple-species agriculture and pastoralism. This system faltered with the onset of cooler conditions (late spring frosts, damp summers, storm damage, disease and blight) at the end of this period in about 350 CE in NW Europe when conditions worsened in 450 CE. Conditions like this would have increased flooding, soil erosion, and nutrient leaching.

Roman occupation

As early as 330 BCE the Greek navigator Pytheas had sailed from the Greek colonial city of Massilia (Marseilles), up the North Sea and past the British archipelago, reaching what he called Thule, probably Norway.

First contact between Britain and Roman culture was likely the trade that occurred between Celtic tribes and Roman merchants in the last centuries of the Iron Age, and it was probably these trade links that attracted the attention of Julius Caesar.

On the continent, Western Europe (Gaul) fell under Roman rule in about 50 BCE, subdued by the army of Julius Caesar, which had forced large numbers of the Belgae tribe of northern Gaul to flee as refugees to the island.

Prior to his victory over Gaul, Caesar had made two reconnaissance visits to the island in 55 BCE and 54 BCE. He called it ‘Britannia’, as a Latinization of the Celtic peoples’ own name for their land, ‘Prydein’ (Britain).

The first visit was a brief foray with two legions and 500 cavalry which was soon abandoned after four days of relentless storms.

The second visit, the following summer, was more substantial, his massive fleet of about 600 ships landing unopposed near Deal in Kent with five legions and 2,000 cavalry, a total of about 27,000 men.[6] He proceeded inland, defeating the southeastern Britons led by Cassivellaunus (who agreed to pay an annual tribute to Rome), and marched as far as the Thames river, then into Essex before being forced to attend to matters in Gaul after a total stay of only 2 months.

The main occupation of Britain did not take place until about 100 years later, in 43 CE, during the reign of Emperor Claudius (10 BCE-54 CE) when four legions of 40,000 to 50,000 soldiers landed at Richborough, Kent, in southern England, led by general Aulus Plautius. Hearing of the Roman landing, the British tribes united under the command of Togodumnus and his brother Caratacus of the Catuvellauni tribe who were defeated at the Battle of the Medway, acknowledged by 11 Celtic kings at Camulodunum (today’s Colchester).

Claudius himself visited this outpost of the Roman empire before his garrisons (about 16,000 legionaries and 16,000 auxiliaries) took up residence in southern and central England and Wales, but especially the southeast. This process was more like assimilation than invasion as tribal kings agreed to pay tribute (tax) in return for Roman protection of their power.

In 60 CE Boadica, Queen of the Celtic tribe of Icini led an uprising in which St Albans (Verulamium), Colchester (Camulodunum) and London (Londinium) were all burned to the ground, humiliating the Roman invaders. According to Roman historian Tacitus, she had no sons and therefore, on the death of her husband king, assumed the role of tribal leader herself, a position refused by the Romans who flogged her and raped her daughters. Following the Roman rout, Governor Suetonius Paulinus returned to slaughter the Iceni, Baodica killing herself to avoid capture.

The soldiers who arrived in Britannia were not necessarily Roman: many had been being recruited or captured from the continental Gallic tribes or elsewhere in the Roman Empire, mainly today’s Romania and Adriatic coasts – and some were from Britain itself. More force was required to subdue Wales, a process that would take until 75 CE.

In 78 Agricola was appointed Governor to Britain, a post he held until 85, during which time he subdued the Ordovices and the powerful Brigantes who occupied land to the north of the Humber. This led to the establishment of three legionary fortresses at Eboracum (York), Deva (Chester) and Isca (Caerleon). There were 10 fortresses built, the largest of these being in Chester, a northern stronghold, its large fortress precinct sufficient to house a garrison of 5000 soldiers and with many Roman remains still visible today.

Invading garrisons were met by Iron Age farmers dressed in animal skins. High ground hill forts were surrounded by earth ramparts and inside these enclosures were round timber buildings with thatched roofs. On lower ground ditches were used to define boundaries of both the living areas and fields, and here there were a few houses of stone and turf.

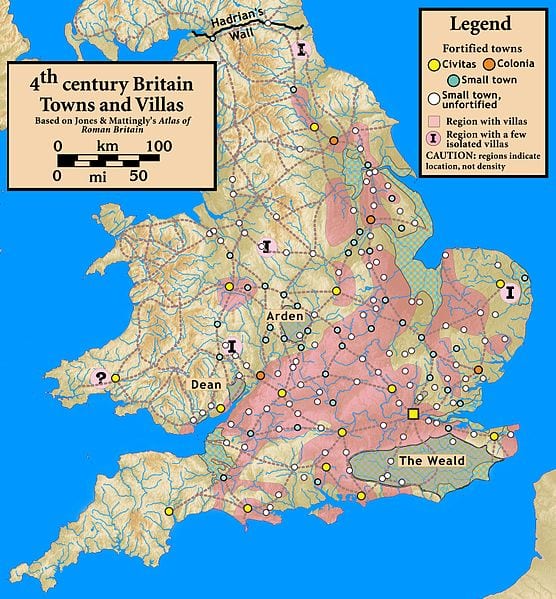

The Britons were forced to adapt to Roman military settlements. Small towns developed around Roman forts at York, Lincoln, Gloucester, and Colchester where military veterans lived, while other towns became administrative centres.

Druidical influence, centred in Anglesey, was perceived as the source of anti-Roman sentiment.

Roman Roads in Britannia

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Roman Towns & Villas

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Population

At the time of Roman occupation in 43 CE the population was probably about two million, Roman technological advances like improved ploughs and the comparative peace during the administration, the Pax Romana, resulted in a further increase in population to perhaps four million by 200-300 CE.

Significantly, the population in later prehistoric and Roman times was larger than at the time of the Norman invasion in 1066. Settlements included farmsteads, hamlet’s, and ‘villages’ sprouted up in thousands, some with rectilinear planned layouts. The first real towns appeared with semi urban settlements.

London

Cunobeline (Strong Dog) was a pre-Roman king from about 9-40 BCE and is mentioned by classical historians Suetonius and Dio Cassius. Many coins, minted in Camulodunum, bea his inscription. He controlled a substantial portion of south-eastern Britain, including the territories of the Catuvellauni and the Trinovantes, and was called King of the Britons (Britannorum rex) by Suetonius. He was also recognized by Augustus as a client king, using the Latin title Rex on his coins. Cunobeline appears in British legend as Cynfelyn (Welsh), Kymbelinus (medieval Latin) or Cymbeline, as in the play by William Shakespeare.

Colchester was selected as the initial capital of Roman Britain with London becoming the residence of the Romon Governor around 120 BCE.

Colchester, as the initial Roman choice, was possibly the oldest town in Britain, the capital of the Trinovantes and later Catuvellauni tribes. The Roman town originated as a legionary base, constructed on the site of a Celtic fortress soon after the conquest by the Emperor Claudius around 40 CE. This early town was destroyed during the Iceni rebellion in 60/61 CE but was rebuilt, flourishing in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.[5] During this time it was known by its official name Colonia Claudia Victricensis and Camulodunum, a Latinized version of its original Celtic name. The population swelled to as many as 30,000 people at its height.

In 55 BCE today’s London was a marshy river embankment. Four years after occupation, a site suitable for continental trade and access to Britannia itself was selected. Here he set up Londinium the emporium, the population quickly growing to about 10,000 people aided by a single wooden bridge that connected the two sides of the River Thames. This bridge would stand for 1600 years.

Despite being burned to the ground during Boadica’s uprising in 61, wooden tablets recovered in 2013 record (in beeswax incised with a stylus) that within two years Londinium was again a vibrant trade centre.

Romans built Londinium as a walled city on the Thames River, a city that linked to both sea routes and roads leading to Britain’s north. A legion of 5000 men could walk over 30 km a day. Market towns were built with a Forum and Basilica and by 100-200CE coinage had been introduced.

Pagan deities were mixed with Roman gods in the temples.

Hadrian’s Wall stretched 120 km from Newcastle to Carlisle in Northumberland taking 3 legions (15,000 men) six years to build.

Londinium reached its Roman height in the second century CE with stone buildings that included a massive basilica and amphitheatre (on the site of today’s Guildhall) that could hold crowds of around 7000 people. A luxurious villa, with hypocaust, has been excavated at Billingsgate and dated to about 190 CE. By the early 3rd century Londinium had a multiethnic, multicultural population of about 30,000 people from distant lands including Africa, the Mediterranean, and Germany. As the hub of the Roman Province of Britannia a city wall was now built around Londinium’s ‘square mile’: it was 6 m tall and 3 m thick (there are remains at Tower Hill), the bricks and masonry probably obtained from a quarry 60 miles away, constructed using slave labour, and completed in 280 CE.

As the Roman Empire faced increasing external threat, in 410 the garrisons were redeployed elsewhere in the empire and Londinium, for over 100 years, was almost deserted.[21]

Caledonia

During the 400-year occupation of Britannia the Romans made three unsuccessful attempts to subdue Caledonia (Scotland). The historical account of these invasions is provided by Roman historian Tacitus.

After the first was 35 years of occupation Emperor Vespasian ordered Governor Agricola to advance up the east coast in 78 CE. The two armies met at the Battle of Mons Graupius in AD 83 or 84. Though the exact location is uncertain and Tacitus’s account questionable, there is no doubt that it was a Roman victory. Controlling the region proved difficult in the face of heavy weather, wilderness, and the hostile Caledonians, so fortresses were built but abandoned in 87 CE.

Later, Emperor Hadrian (76-138 CE) visited the island in 122 CE, beginning the massive six-year construction of the 118 km long Hadrian’s Wall. This extended from east to west across the north of the island between the Tyne and Solway Firth, serving as a military defence with security check points. It remains today as a well preserved monument from antiquity.

The second invasion was at the request of Emperor Antoninus Pius which eventually resulted in the construction of a stone and turf wall between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde in the years 142 to 154 CE, the Antonine Wall, which pushed the northern boundary to the narrowest point of lowlands between the Clyde and Forth Rivers.

A third and final attempt was made by Emperor Septimus Severus (r.193-211 CE) in c. 208 CE which re-established legions at the wall and carried out repairs: but with challenges emerging in other parts of the empire soldiers were withdrawn for service elsewhere in the empire. They did not return.

The Romans occupied the whole of the area now known as Wales, where they built Roman roads and castra (fortresses), mined gold at Luentinum and conducted commerce. Interest in the area was limited because of the difficult geography and shortage of flat agricultural land. Most of the Roman remains in Wales are military in nature. Sarn Helen, a major highway, linked North and South Wales.[WP]

Roman Britain

The Britons gradually adapt to the Roman military settlements, witnessing the rise of new townships, a new road system, and long-distance trade. It was a highly organized and legalistic culture. During the Roman Republic from 509 BCE to 27 BCE a regular 5-yearly census assessed the rights of male citizens while at the same time indicating potential military strength and tax revenue. Roman garrisons were a mobile military presence that stimulated the spread of goods and ideas including the introduction of new foods, plants, and plant husbandry techniques, notably the production horticulture used for vegetables, fruits, herbs, and nuts now cultivated in market gardens and orchards as cash crops to be sold at market to the military and townsfolk.

Romans brought horticultural practices and plants from the Mediterranean.

This Roman period was an important social transition marked by the advent of distinct social consumer groups, new plant foods and new methods of food husbandry. Associated with this social change was a demarcation of four social classes or consumer groups: the military (about 10% of the population at first), townsfolk especially around London, a group from rural SE England and lastly those of rural SW England together with N England, Wales and Scotland. Of these four groups the first three had access to the new ‘Roman cuisine’.

Roman landscape alteration

Romans began an intensive program of land reclamation in eastern England, by draining the Fens, an uninhabitable region of shallow sea and tidal marsh. Reclaimed land was given to the Britons and canals which led from this region inland were used by barges carrying agricultural produce.

Celtic plant diet

Roman interest in plants extended to decorative gardens, avenues of trees and other civic displays but it was by the introduction of new food plants, including herbs and spices, that they were probably remembered by the Britons.

The Celtic diet consisted mostly of wheat, barley, peas, broad beans, linseed and flax grown either for themselves or as tribute to their chiefs (see Celts & Druids). Land had been cleared for agriculture which was based mostly on the cereal wheat, and there was cattle farming which provided meat and milk.

Native trees were mostly ash, hazel, birch and holly. There were no gardens. Archaeologists have found iron sickles and grinding stones (querns) used to produce flour from their wheat. Pollen analysis has revealed the use of fruits like crab-apples, wild pears, strawberries, and sloes.[4] Though hardly gardening it seems that there were areas protected from interfering livestock by hedges of hazel and hawthorn. Iron Age vegetables included carrots, beet, brassicas, asparagus, and Fat Hen (Rumex, or Dock), broad bean, beet, and the celery-like Alexanders and even peas, onion-couch, mint, coriander, and even opium poppy (the result of trade). Around the country the Romans found sacred groves often marked by a special tree or spring of water and many of these were often adapted to become Roman shrines.

Commentary

With the decline of the Roman Empire garrisons were withdrawn in about 410 CE. Intermarriage with the Britons was practiced, and many soldiers remained in the British Isles.

Britain was occupied by Roman garrisons for about 400 years, from c. 45 CE to 410 CE, when it became the westernmost extension of the world’s most extensive and sophisticated culture. The occupation left on Britain an indelible imprint of the classical world. Though the Roman Empire would fall, to be followed by a Medieval period lasting about 1,000 years, it would be the Roman cultural and administrative traditions that would be emulated by Britain as it established, in the 18th and 19th centuries, its own more far-reaching Empire and colonies, including Australia.

With the influx of Romans, Britain suddenly experienced a culture with a sophisticated and complex social organization. This degree of social complexity would not be attained again in Europe until the 18th and 19th centuries: a highly disciplined and well-equipped army; a modern bureaucracy; trade, commerce, and manufacturing on a vast scale; metal coinage; technology, architecture, art, literature, law, and government to a level of sophistication that had never been seen before. Towns were carefully planned and constructed with shopping precincts, basilicas, baths and buildings with painted frescoes and mosaics to cope with armies, merchants and a Roman bureaucracy as mobility of people and resources rapidly increased along the carefully planned and constructed sea routes and network of roads across Europe. Intermarriage and the new trade would have challenged former tribal affiliations. Even so, Latin did not replace the Celtic language as it had done in Gaul although it was the language of the ruling class.

British conquest did not mean total land appropriation as sympathisers and retired soldiers would be given land grants. Landowners were known and recorded. Tribute to Rome expected in the early days as labour or military service, and later as money.

At least four methods were employed to run farms: family ownership; tenant farming (sharecropping) in which the farmer and a tenant share the farm profits; an estate run by an aristocratic landlord with slaves and Roman overseers; leasing by land owner to tenants who would run the farm . These larger highly managed estates were pejoratively termed latifundia by Cato.

Whatever ideas and garden practices and ideas the Romans absorbed from other cultures it is from their culture that Europeans and the British we have built our underlying assumptions about garden structure and function. From the British these basic ideas have been passed on to the Neo-Europes, with only minor adjustments although it would seem that for Romans the garden was just one facet of a broader activity, agriculture, and a wider space, the farm or villa estate – which for Cato consisted of nine elements: vineyard, garden, osier-bed, olive grove, meadow, grain field, wood lot, orchard, and nut grove. Of course this is an interpretation of the garden from the point of view of the wealthy land owner. We know little of the urban garden (although town houses also had gardens) but its influences lay in these grander gardens.

Much of the framework of the English countryside was already laid out in prehistoric times with Roman structures, like the famous Roman villas, superimposed on former farmsteads.

In 410 CE the Romans left a well-populated nation with cultivated fields, towns, roads, villages, farmsteads, sophisticated water supplies (aqueducts) to the larger towns, and a planned system of land tenure.

For the British the arrival of Roman garrisons marks the boundary between prehistory and history as it was the Romans who initiated Britain’s written historical record. To the Iron Age island Occupying forces brought a form of governmental, bureaucratic, economic and legal system that was directed from across Europe in Rome. Troops had burst onto the east coast with a formidable navy and military machine. There was engineering on a scale never seen before in Britain (hard-surfaced roads, monumental buildings, viaducts, monumental architecture and sculpture), not to mention medicine, and trade with the Mediterranean that included luxury goods and new medicinal and economic plants. With London as the communication hub four great highways fanned out to the north, northwest, west and southwest.

Rome took full advantages of Britain’s resources which included coal, iron, jet (lignite), lead, salt, gold, silver and the Cornish tin that was so useful in the production of bronze armour. Britons gained much from Roman technical and social know-how but paid a despised poll tax (per capita) tributum capitis, a sales tax, and a 5% inheritance tax.

From the third century, as Rome declined, larger towns, like London, were walled and, as the last troops were withdrawn in 410 to shore up weak defences in Europe, many Britons would have preferred them to stay.

In the plant world the Roman presence in Britain was marked by new practices and technology for agriculture and horticulture – and permanent landscape change.

This Roman period was an important social transition marked by the advent of four social consumer groups based on their access to new plant foods and new methods of food husbandry: the military (about 10% of the population at first); townsfolk, especially around London; a group from rural SE England; and, lastly, those of rural SW England, northern, Wales, and Scotland. Of these four groups the first three had access to the new ‘Roman cuisine’.

Imperial Rome bequeathed to European society the model of a sophisticated economy employing resources from its subjugated provinces.

Britain was a Roman source of gold, silver, and tin while in Dorset wheat and oats were accumulated in storage pits. Land owners were a social elite with political power in the city and the possession of land was a mark of honour, grants of land being given, for example, by leaders to soldiers who distinguished themselves in combat.

Traditions

Many British traditions, especially those of the British imperial era, can be linked to Roman Britain, the aristocratic estates so similar to the gentleman farmers of Rome, political power linked strongly to wealth, the Roman Senate consisting of an aristocracy, emulated until recent times by the English House of Lords.

Life of the Britons before Roman settlement was extremely simple when compared to that of the Romans who brought with them the accumulated experience of Mediterranean and east Asian peoples and the world’s most effective application of ‘scale’ to human affairs – large numbers of people, organized hierarchically, with a division of labour that enabled the development of coined economy and the capacity to store information through the written word, specialized technologies, not least those associated with combat and conquest, and the production of armour and tools.

This vast empire was governed by an extensive bureaucracy and strict rule of law that emanated from an administrative centre thousands of miles away from Britain in Rome. ‘Scale’ was a way of harnessing energy to produce ‘things’ that were bigger and more effective than anything the British had ever seen: large enclosed ocean-going vessels; secure houses made of rock; well-constructed roads to carry much-needed resources over long distances; and for the houses of the well-to-do there were the trappings of opulence, the mosaic floors, wall frescoes, inner courtyards, plants in pots, piped water, underground heating and heated baths, luxury goods, exotic foods and spices. It was the culmination of a form of social organization that had emerged millennia before in Mesopotamia, Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean.

After the decline of this empire it would be over 1,000 years before the Renaissance, based on a revival of the classical learning and traditions, would set in motion the movement towards a society with similar capacities.

At its height Rome had a population of over a million people, the largest city the world had known, the first modern city to exceed these numbers being Victorian London. It was a multicultural society of slaves and ‘outsiders’ with specialist traders and merchants devouring resources from around the known world along the most elaborate and robustly constructed roads the world had seen. Merchant ships using the port of Ostia. Within the city were promenades, parks and gardens and sheltered meeting places especially along the River Tiber, although the most magnificent villa gardens were owned by aristocrats living outside the city, escaping the heat of the city in summer to live in the cooler mountain slopes, alongside lakes or on the Mediterranean coast. Wealthy farmers with rural estates would work in the city, their rural estates under special management until they returned to enjoy the rural charm. Apartment blocks, called insulae, would display pot plants on windowsills, and climbing plants were trained on pergolas and balconies, and in later times trees were planted in avenues along the roads.

By 60 CE London was a bustling trade centre with specialist foreign tradesman, shipbuilders, potters serving a total British population of probably between 2-5 million people including the 40,000 to 50,000 soldiers and 10,000 to 20,000 administrators and merchants. Associated with Roman forts were civilian cities with a rectilinear street layout, buildings and squares, water supplies, baths and markets. Britain’s Roman Governor lived first in Colchester (Camulodunum) moving in the 1st century CE to London (Londinium) which had become the national centre with about 30,000 inhabitants.[20]

In the third century CE Rome was experiencing shortages in man-power as non-Roman populations thrived. The Roman occupation, though initiated for commerce and profit, had introduced an internal forced peace Pax Romana and administration that made it easier for country people to do their work. There was also now a proportion of Romano-British inhabitants. When the garrisons were eventually withdrawn in 410 CE, their departure was not greeted with universal celebration.

Timeline

BCE

55 – Caesar’s first reconnaissance expedition lands on south coast, remaining for two months

54 – second and more substantial force marches inland beyond the Thames and into Essex

CE

43 – Roman invasion ordered by Emperor Claudius and led by general Aulus Plautius is resisted by Caratacus. Founding of Colchester (Camulodunum) as the oldest Romano-British town in the colony of Britannia

50 – defeat of Caratacus

51 – capture of Caratacus

61 – Iceni uprising under Boadicca who commits suicide

74 – Petilius Cerialis leads battle against Brigantes

78 – British Governor Agricola begins conquest

85 – foundation of Lincoln

98 – foundation of Gloucester

122 – Emperor Hadrian visits Britain initiating construction of ‘Hadrian’s Wall’

126 – Hadrian’s Wall completed

211 – Emperor Septimus Severus dies in York

212 – all free citizens of Britannia declared eligible to become Roman citizens

304 – St Alban the first British Christian martyr

306 – western Emperor Constantius dies in York

312 – provinces in Britannia now four

383 – Magnus Maximus becomes Emperor of Britain and Gaul

405 – mission of St Patrick begins

407 – Roman Army in Britain declares Constantine emperor (lasts until 411)

410 – Roman legions withdraw from Britain

449 – invasions by Germanic tribes called Angles, Saxons, and Jutes with Vortigern the British leader

477 – South Saxons under Aelle begin settlement

495 – West Saxons under Cerdic begin settlement

Roman emperors known to have visited Britain

Julius Caesar 55 & 54 BCE

Claudius 43 CE

Vespasian 43 CE as Legate of Legion II during the invasion

Hadrian 122 CE

Pertinax Governor of Britain during the late 2nd Century

Clodius Albinus 193 CE Governor of Britain

Septimius Severus 207-211 CE died in York

Caracalla 207-211 CE

Geta 207- 211 CE

Carausius 287-293 CE

Allectus 293-296 CE

Constantius I 296 CE died in York 306 CE

Constantine the Great 306-307 CE

Constans 346 CE

Magnus Maximus 383 CE Army commander (possibly with son Flavius Victor)

Constantine III 407 CE Army commander (possibly with son Constans)

POPULATION OF BRITAIN[1]

millions

B = Britain, E = England

W = Wales, S = Scotland

200 - 2.9 B

400 - 3.6 B

1100 – 2.0 B

1300 – 5-6 E

1550 – 3 EW

1600 – 4 EW

1700 - 6 EWS

1750 – 6.5 B

1800 - 10.5 B

1850 - 27.4 B

1900 - 38.2 B

1950 - 50.2 B

2000 - 59.1 B

2010 - 63.0 B

POPULATION OF LONDON[1]

100 - 35,000

200 - 60,000

1100 – 18,000

1300 – 80,000

1400 – 10,000

1500 - 65,000

millions

1800 - 1

1900 - 6.5

1940 - 8.6 (peak)

2000 - 7.2

2010 - 8.2

ROMAN EMPERORS

1st CENTURY CE

Augustus - 31 BCE –14 CE

Tiberius - 14–37

Caligula - 37–41

Claudius - 41–54

Nero - 54–68

Galba - 68–69

Otho - Jan,-Apr. 69

Aulus Vitellius - July–Dec. 69

Vespasian - 69–79

Titus - 79–81

Domitian - 81–96

Nerva - 96–98

2nd CENTURY CE

Trajan - 98–117

Hadrian - 117–138

Antoninus Pius - 138–161

Marcus Aurelius - 161–180

Lucius Verus - 161–169

Commodus - 177–192

Publius Pertinax - Jan.-Mar. 193

Marcus Julianus - Mar.-Jun. 193

Septimius Severus - 193–211

3rd CENTURY CE

Caracalla - 198–217

Publius Sept. Geta - 209–211

Macrinus - 217–218

Elagabalus - 218–222

Severus Alexander - 222–235

Maximinus - 235–238

Gordian I (Mar.-Apr.) - 238

Gordian II (Mar.-Apr.) - 238

Pupienus Max. (Apr-July) - 238

Balbinus (Apr.-July) - 238

Gordian III - 238–244

Philip - 244–249

Decius - 249–251

Hostilian - 251

Gallus - 251–253

Aemilian - 253

Valerian - 253–260

Gallienus - 253–268

Claudius II Gothicus - 268–270

Quintillus - 270

Aurelian - 270–275

Tacitus - 275–276

Florian (Jun.-Sept.) 276

Probus - 276–282

Carus - 282–283

Numerian - 283–284

Carinus - 283–285

Diocletian (E Empire) 284–305

- divided empire into E and W

Maximian (W Empire) 286–305

4th CENTURY CE

Constantius I - W 305–306

Galerius - E 305–311

Severus - W 306–307

Maxentius - W 306–312

Constantine I - 306–337 (reunif.)

Galerius Val. Max. - 310–313

Licinius - 308–34

Constantine II - 307–340

Constantius II - 337–361

Constans I - 337–350

Gallus Caesar - 351–354

Julian - 361–363

Jovian - 363–364

Valentinian I - W 364–375

Valens - E 364–378

Gratian - W 367–383

- coemperor with Valentinian I

Valentinian II - 375–392

Theodosius I - E 379–392

E& W 392–395

Arcadius - E 383–395

- coemperor

395–402 sole emperor

Magnus Maximus - W 383–388

Honorius - W 393–395

- coemperor

395–423 sole emperor

5th CENTURY CE

Theodosius II - E 408–450

Constantius III - W 421 co-emp.

Valentinian III - W 425–455

Marcian - E 450–457

Petronius Max. - W Mr–My 455

Avitus - W 455–456

Majorian - W 457–461

Libius Severus - W 461–465

Anthemius - W 467–472

Olybrius - W Apr.-Nov. 472

Glycerius - W 473–474

Julius Nepos - W 474–475

Romulus August.- W 475–476

Leo I - E 457–474

Leo II - E 474

Zeno - E 474–491

Timeline – Roman and Byzantine Emperors

Dieu le Roi – 2020 – 11:56

The Entire History of Roman Britain (55 BCE – 410 CE)

History Time – 2020 – 1:38:04

Ancient Rome in 20 minutes

Arzamas – 2017 – 20:58

Roman Empire. Or Republic?

CrashCourse – 2012 – 12:25

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . substantive revision 7 August 2020

. . . 3 July 2023 – minor upgrade

Roman Empire at its peak under Emperor Trajan in 117 CE

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons