Horticultural literature

Title page of John Loudon’s monumental Encyclopaedia of Gardening – 1865

Image: Roger Spencer 10 July 2017

This article covers early British and European gardening literature. For a global account of plant literature up to about 1800 see Plant literature to 1800. For an account of Australian gardening literature to the present day see Australian gardening literature. There is an online copy of British Botanical Literature before 1800 published by Blanche Henrey in 1975.

Introduction – Horticultural Literature

It was horticultural literature that was among the first books and pamphlets to be printed. Even in the new Colony of New South Wales books on gardening soon arrived.

Few of Australia’s new settlers could read, but the educated among them would have been aware of horticultural and botanical developments in England. Isolated on the opposite side of the planet these colonists would look to the literature of the motherland not only for practical guidance but as a way of keeping in touch with the gardening fashions and foibles of the day, knowing that their new home was the source of great scientific and horticultural interest in distant England.

British literature available in Australia c. 1790 – 1850

At the time of Australian settlement English society was gripped by an unprecedented obsession with plants. Australia was a part of this plant craze that has been called ‘botanophilia’.[21] In the gardens of the wealthy an already large palette of ornamental plants was being supplemented by new treasures from Britain’s expanding colonial empire, especially the Americas. The number of nurseries had exploded to meet the needs of the newly affluent middle classes that were beginning to reap the financial rewards of these colonies and the Industrial Revolution as the fascination for ‘exotick’ flora and fauna filtered down from royalty and their wealthy social betters. As an era of adventurous scientific voyages of exploration and discovery across the globe, plants were at the centre of attention. Brought back as seed, herbarium specimens and even living plants these botanical treasures were lovingly nurtured into flower in the state-of-the-art hothouses and conservatories of botanic gardens and the well-to-do of the day. All of this social phenomenon was reflected in the books, periodical, magazines, scientific literature and newspapers of the day.

European context

Horticultural books of the early 18th century still looked back to the herbals and the ancient classical texts but by the early 19th century there had been great social change as well as a leap forward in the technology of the printing industry. Accurate colour plates were now demanded for true-to-life colour representation of plants as portrayed by professional botanical artists, and larger print-runs were expected. Printers were up to the task as in the 1820s and 1830s excise on printing paper was reduced, paper-making became mechanized, presses improved, stereotypes were invented, and copperplates were replaced by lithographs.[9]At least 16 new gardening magazines were founded in Britain in the 1830s, although 12 of these ceased publication in the same period, which gives some idea of the commercial frenzy of the day.[10]

This was now work of the highest quality on all fronts, and colour reproductions of the early 19th century have only been surpassed in recent times with the advent of computer technology.

Scientific literature

For those few whose business was plants, especially botanists, it was critical to keep up-to-date with what was going on in Europe. As a starting point there were the books and articles written by European botanists describing the Australian flora (see Navigators and explorers). In the earliest days these combined the business of scientific description with ornamental horticulture as the first scientific descriptions were made from plants in cultivation and illustrated in popular journals.

Over the period of 1790 to 1850 scientific communication through the written word was revolutionized as few, poorly indexed and under-funded journals were transformed into specialist works in meticulous formats catering for colonial audiences and serving as the major means of scientific communication.[2]

Von Mueller, at first working almost single-handedly, had already amassed a large library of books when in 1855 he wrote to William and Joseph Hooker in Kew, London saying that he would ‘… devote £100 per annum on books’ these to be purchased at the discretion of the Hookers.[1] Accordingly Mueller received a regular delivery of both books and periodicals many of which were detailing the botany and horticulture of plants that had been sent to England from the new colony, their first botanical descriptions made from plants grown in cultivation. Mueller’s extensive library now forms the basis of the library collection held at the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

Mueller, with the support of the Hookers, had published in the Journal of Botany and Kew garden Miscellany first making his mark with Flora of South Australia … published in 1853,[11] followed by articles on the Swan river and Brisbane flora by Charles Fraser who was in charge of Sydney Botanic Gardens while Hooker would publish himself lists of plants submitted to him by Australian collectors like James Drummond and Ronald Gunn.[29]

Perhaps the most significant of the British journals was Hooker’s Annals of Botany in which Jonas Dryander, a student of Linnaeus and librarian to Joseph Banks first published, after long delay, a n account of some of the plants collected by Banks and Solander on Cook’s voyage of the Endeavour.[27] With the revitalization, mostly by Joseph Hooker,of the Linnean Society in London, one of the few places for publication was the Journal of Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, Botany where Mueller published on Eucalyptus and Acacia in 1858 and 1859. Australian publications also appeared in the journals Bonplandia and Journal of Botany, British and Foreign.[28]

It would be a long time before the new colony could produce its own scientific literature. Botanical periodicals first appear in Australia when Mueller, generally supported by William Hooker in publishing his work found that there was no longer an outlet for his work on the Gregory expedition to Australia’s north. This prompted the publication in 1858 of the first 24 page Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae. It was the dawn of Australian botanical independence. For Australia’s botanical community this saved time, giving immediate access to local scientific research: it also allowed the creation of a botanical vision for the future that was based in Australia not London. But it was a long time coming.

Botanical and horticultural magazines

Apart from scientific journals there were horticultural periodicals produced both in Britain and in Australia. From this literature we can get an insight into the horticultural thinking of the day.[20]

Works were sometimes produced as collectors’ items in a series of large format folios bound in red or blue morocco leather, they avoided the Latin so often used before and they catalogued the first introduction of exotic plants to cultivation in the British Isles from places like Australia.

For more detail on botanical illustration, printing techniques see here.

Botanical and horticultural periodicals were a way of introducing an eager public to the new plants that were being introduced from distant countries. Many of these journals were the work of keen nurserymen, the illustrations produced from engravings and then hand-coloured. Apart from luring wealthy clients with the latest horticultural treasures they also acted as important botanical records because, in many cases, the first desciptions of new species were drawn up from cultivated specimens described and illustrated in these magazines, and because in some cases no herbarium specimens have survived these illustrations serve as type specimens.

As a means of portraying plants in colour from lithographs these magazines were a great avenue for botanical artists to display their talents, this period marking a critical phase in the development of botanical illustration.

With the early 19th century there is a noticeable shift in the plant information provided as the early preoccupation with the description of botanical novelties gave way to advice on their cultivation partly because they were becoming more familiar but also, no doubt, driven by the need to encourage a wider readership stimulating a plant fascination in the newly wealthy upper middle class.[3]

A brief outline of some of the major horticultural magazines of these times will give an impression of the strong Australian connection that existed at this time.

The Botanical Magazine

Interest in the new plant introductions was stimulated by a spate of fashionable illustrated gardening periodicals that included descriptions, illustrations and cultivation notes.

Foremost among the enthusiastic pioneers in this field was William Curtis (1746-1799) who, from 1777 to 1798 produced an attractive six-volume octavo compendium Flora Londinensis an urban flora describing the wild plants growing within a 10 mile radius of London and beautifully illustrated with the hand-coloured copperplate prints of talented botanical artists James Sowerby (1757-1822), Sydenham Edwards (1768-1819)and William Kilburn (1745-1818). However, it was the print run of 3,000 copies of the much cheaper (1 shilling per issue) The Botanical Magazine; or Flower Garden Displayed, first published in 1787, that really secured his popularity. Curtis was ideally situated for such projects having a botanical background as an apothecary, ‘demonstrator of plants’ and Praefectus Horti (Head Gardener or Director) at London’s Chelsea Physic Garden as well as being a keen gardener himself, opening to the public his botanic-garden-cum-nursery first at Lambeth Marsh in 1779, and then Brompton in 1789.[4]

The illustrations in this periodical were hand-coloured engraved plates. Up to 1800 only eight Australian species had been illustrated (?11). The first, plate 100 (?110), Acacia verticillata appeared in 1790 and was of a plant under cultivation in William Malcolm’s nursery at Kennington, then in 1791 a New Zealand Sophora tetraptera growing at the Chelsea Physic Garden from seed collected on Cook’s first voyage. These were followed by Metrosideros citrina (now Callistemon citrinus) in 1794 and various legumes.[5] It would continue publication until 1983. After a period in the doldrums the magazine was resurrected by the hard work of William Hooker who became editor in 1827 producing 670 of the improved-quality plates himself through the next 10 volumes.

The Botanist’s Repository

New Holland plants were more widely publicised in The Botanist’s Repository published and illustrated by Henry Andrews and first published in 1797 with assistance from his father-in-law John Kennedy of the nursery Lee and Kennedy which stocked Australian plants, many collected and sent as seed by William ?Peterson, and this was the source of many illustrations (the nursery and its owner are commemorated in the genus Kennedya). In spite of its title the content was more on cultivation than that of the Botanical Magazine. Forty New Holland species were illustrated in the first four volumes before the journal ceased publication in 1815 after a total of ten volumes.[6]

Botanical Register

With an initial circulation of about 3,000[7] it is not surprising that the style of The Botanical Magazine was soon followed by others, the competition and high cost of hand-colouring threatening its existence. In spite of changing hands several times and later poor sales it is nevertheless the oldest horticultural magazine still flourishing. The botanical artist was Sydenham Edwards who joined forces with J.B. Ker, who also contributed to the Botanical Magazine, to found the Botanical Register in 1815 which also struggled, even after its amalgamation with Robert Sweet’s British Flower Garden in 1839.

Editorship of the Botanical Register had passed to John Lindley in 1829 who at that time was Professor of Botany at the University of London and Secretary to the Horticultural Society who raised its botanical profile. Altogether Lindley described 281 new species and 18 genera in this magazine.[8] Each description was accompanied by a high quality hand-coloured plate (a feature retained until 1948) and cultivation notes. This magazine constitutes possibly the best record of horticultural fashion and Australian plants in Britain over a period of 200 years. Up to 1864 more than 450 of its entries were from Australia, the descriptions drawing on the collections of James Drummond a collector from Western Australia. The First Australian plant illustrated was Correa virens (now Correa reflexa) in Plate 3.

Botanical cabinet

These magazines were followed from 1805 to 1808 by Salisbury’s Paradisus Londinensis, and in 1815 by Sydenham Edwards’ Botanical Register.

In 1771 the Dutchman Conrad Loddiges and Sons’ bought a nursery in Hackney that became very successful, importing new plants especially from America and publishing many of them (illustrated by his son George Loddiges) in the 20 volumes published between 1817 and 1833 as the Botanical Cabinet.

The botanists providing the plant descriptions in periodicals and magazines were not always known as in Curtis’s Bot. Mag. In the Botanical Register it was thought to be J. Lindley and J. Ker-Gawl, in the Paradisus it was Salisbury; in the British Repository they were attributed to Andrews but gardeners and others assisted. John Kennedy was Andrews’s father-in-law and was responsible for the descriptions in the first 5 volumes.[22]

Popular horticulture

Popular horticulture journals were introducing the British public to the new plants from overseas, like the journal The Naturalist’s pocket Magazine, or Compleat Cabinet of the Curiosities and Beauties of Nature which, in 1798, illustrated a fruiting specimen of Banksia serrata ‘copied from an original drawing actually made in New South Wales from the living plant’ then in 1800, Banksia spinulosa.[30]

Of the 16 new gardening periodicals that hit the market in Britain in the 1830s twelve were to collapse.[10] There was Paxton’s Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants of 1834 (Joseph Paxton who designed Crystal palace for the 1851 Great Exhibition) which proved popular, continuing for 16 volumes. John Loudon’s Gardener’s Magazine and Register of Rural and Domestic Improvement was another quality periodical in a field of also-rans.

Dictionaries, encyclopaedias, catalogues and lists

Modern-style alphabetically-arranged horticultural encyclopaedias have been produced for about 300 years now with the need arising towards the time of discovery of the plants of New Holland in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was at this time that plants were pouring into the gardens of western Europe from southern Europe and the colonies of the Dutch, French and British being distributed mainly from the gardens of Amsterdam, Leiden, Paris and Chelsea. After an initial phase of when new introductions were described and illustrated in periodicals, there was a period of consolidation with encyclopaedias, dictionaries and other compendia summarizing the plant stock that had become available in Britain. Outstanding among these compendia was, first, Philip Miller’s (1691-1771) The Gardeners and Florists Dictionary … which passed into 8 editions, the 8th edition of 1768 noted for its adoption of Linnaean binomial nomenclature. John Claudius’s Loudon’s An Encyclopaedia of Plants with three editions between 1829 and 1855 listed tens of thousands of species and had several supplements between 1829 and 1880. His erudite writing on all manner of horticultural subjects from individual plants to garden styles to cemeteries was to significantly influence horticulture in Australia, as elsewhere, much of his work still of relevance today.

The Aitons’ Hortus Kewensis

Kew publications were a valuable record of early plant introductions. Scottish botanist William Aiton travelled to England in 1754 to become assistant to Philip Miller who was superintendent of the Chelsea Physic Gardenand in 1759 Aiton was appointed director of the newly established botanical garden at Kew. In 1789 he published Hortus Kewensis, a catalogue of Kew’s plants. Both Daniel Solander and Jonas Dryander had contributed to this catalogue in which they published many of their new species. William Aiton’s son William Townsend Aiton produced a second edition of the work in 1810 to 1813, this time with the help of Dryander and Robert Brown.[19] This compendium (including those from Australia).

There are also specimens in the British Museum that pre-date settlement.

Books

Specimen of the Botany of New Holland

Written by James Smith and published by its botanical artist James Sowerby A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland (1793) was the first book devoted exclusively to New Holland plants Although Dampier had included engravings of several plants in his travelogue of 1701?. Published in four parts between 1793 and 1795 A Specimen … comprised 16 coloured plates based on sketches and specimens sent from New Holland by Surgeon General John White of the First Fleet and 40 pages of text including original plant descriptions written by James Smith. This was followed in 1804 by Exotic Botany which included 39 illustrations of Australian plants, although only two volumes were published.

John Cushing, Foreman to the Lee and Kennedy Nursery in Hammersmith London, in 1811 produced a publication on the hot-house care of the new warm climate plants coming into England called The Exotic Gardener.[23] This must surely count as the first book giving an account of the cultivation of Australian native plants.[24]

Flora Australasica containing 56 coloured plates was published by Robert Sweet in 1827-1828.

The Loudons & the Australian connection

The zenith for Australian plants in Britain lasted from about 1800 to 1835 and this enthusiasm was fuelled by travelogues and other books along with a plethora of botanico-horticultural illustrated periodicals. The literature of these times[32] is outlined by E. Charles Nelson.[33]

Without doubt the most prolific end trenchant horticultural chronicler of the early nineteenth century was J.C. Loudon. His publications covered in astonishing detail the horticultural matters of the day so that it can be said with some confidence that his output and depth will never be paralleled. He established his oevre with the successful An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1822) followed up by The Encyclopedia of agriculture (1825), as a link between he horticultural community as a whole there was the Gardener’s Magazine (1826-1844), first truly horticultural magazine in the UK and an invaluable source of horticultural knowledge, information, reviews and the activities of horticultural societies: several Australians contributed to its pages). This was followed by the Magazine of Natural History (1828). His predilection for massive compendia continued with The Encyclopedia of Plants (1828), Hortus Britannicus (1830), The Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, Villa Architecture (1834), Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838), Suburban Gardener (1838), The Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs (1842) and On the Laying Out, Planting and managing of Cemeteries (1843).

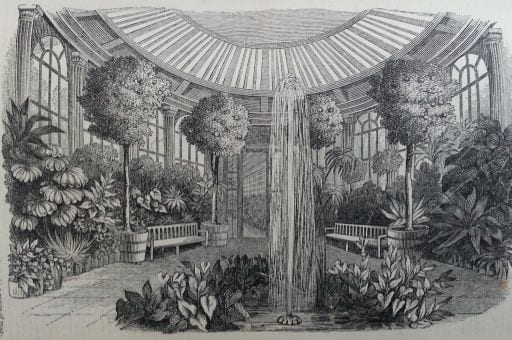

One of many exquisite etchings in Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Gardening – 1865

Image: Roger Spencer – 10 July 2017

Both John and Jane Loudons’ many and extensive works were well known and readily available in British colonies and especially Australia where, for example, the first edition (1813) of An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture carried imprints of Howe (Sydney) and Melville (Hobart Town) alongside the familiar name of Longman.[13] No doubt the Encyclopaedia of Gardening likewise served as a source of all manner of gardening information. It was in the more modest gardening style of the suburban villa garden that the influence of the Loudons was felt. An Encyclopaedia of Agriculture likely encouraged the use of plantations and arboreta.52

It was in the 1820s and 1830s that ornamental rather than subsistence gardening evolved in Australia with new introductions to the botanic gardens in Sydney (1816) and Hobart (1818). Compatriot Scotsman Alexander Macleay arrived in the new colony in 1826 (the year that the ?Loudons published the first issue of the Gardener’s Magazine, which kept colonists up-to-date with the horticultural developments); he had been, like Loudon, a Fellow of the Linnean Society. Charles Fraser wrote to Loudon in 1828 with a ‘List of Fruits Cultivated in the Botanic garden, Sydney’ which was published in the Gardener’s Magazine and there was also correspondence with James Anderson (collector for Hugh Low of Clapton Nursery) and others: seed were sent to him by John McLean (it was assumed that keen horticulturists would keep up-to-date by reading the Gardener’s Magazine).[14]

The first terraced vineyard in Australia was set out by Frederick Meyer (1790-1867) who brought Loudon correspondence to Australia in 1830. Residents contributed occasional articles to the magazine. John Thompson (c.1800-1861), a surveyor in Sydney and keen correspondent with Loudon was a landscape gardener who had worked on Hyde Park in London and also made suggestions for the improvement of Sydney’s Hyde Park, and illustrated plants and trees of New South Wales and Tasmania.[15] The first Australian book devoted to landscape gardening was Thomas Shepherd’s Lectures on Landscape Gardening in Australia (1836) (which appeared five years before America’s first major book by Andrew Downing on the same topic).[16] This was reviewed by Loudon, who seems to have been its inspiration,[17] in his magazine.

Loudon promoted, in his Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion (1838) the Gardenesque style which was recommended for the “newly peopled, and thinly inhabited, countries, such as the back settlements of America and Australia”.[18] The grouping of plants according to a botanical classification system, done in Melbourne by Mueller and Moore in Sydney was recommended by Loudon were possibly under the greatest influence of his ideas. Sydney’s Rookwood Necropolis was established as a garden cemetery based on examples in America and Britain, and likely influenced by Loudon’s On the Laying Out, Planting, and Managing of Cemeteries, and on the Improvement of Churchyards (1843).[25] Moore was responsible for the layout of many parks and gardens including Centennial Park and the drives and early plantings at Rookwood . In Victoria Ferguson made several references to the Gardenesque style of Loudon which prevailed in Australia, albeit less precisely applied, throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.[26]

There is little doubt that the educated Australian gardeners would have accessed at least some of these works, notably the Suburban Gardener.

Gardeners’ Chronicle

The Gardeners’ Chronicle, founded in 1841 by the horticulturists Joseph Paxton, Charles Wentworth Dilke, John Lindley (the first editor), and William Bradbury, was a later but major addition to horticultural literature that would continue for nearly 150 years cvering all aspects of gardening with contributions from notorieties like Charles Darwin and Joseph Hooker. Garden historian Edward hyams described it as follows: ‘… the professional’s paper, but it was soon being read by advanced amateur gardeners and it opened the way for the foundation and growth of the popular gardening press which has advanced the craft of gardening and the quality of gardens among tens of millions of people all over the world‘.[31]

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

With the exception the local newspapers and a few local publications it would be this European literature, mostly English, reflecting their interests and preoccupations that would dictate the literature found in Australian for about the first 50 years of settlement before a degree of literary and scientific independence could be claimed. By the late 1830s popular British interest in Australian plants was on the wane prompted by new interests in Asia and the difficulties that had been encountered in the cultivation of Australian native plants.

It was a period of British ascendancy and scientifically was under the control of men at Kew, first Banks and then Willliam Hooker and his successor as Director, son Joseph. As part of a massive inventory of plants growing throughout the British Empire Mueller was to collaborate with George Bentham in the production of the seven-volume Flora Australiensis, (1863-1878) a combined tour de force between one of Kew’s greatest botanists and an expatriate European, marking the last vestiges of colonial control from Kew at a time when Australia was at last charting its own botanical course. From now on Australia botanists would come largely from the ranks of the native-born.

Sustainability

As a driver of social organization, technological change and environmental impact it would appear that the Plant literature of colonial settlement had relatively little influence.