Human-talk

An AI-generated image of a plant with an eye.

Human-talk gifts organisms – including their structures, processes, and behaviors – with human-like characteristics

What were the preconditions in nature that made subjectivity possible?

Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling – 1775-1854

In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.[3]

Charles Darwin (1859). The Origin of Species . . . p. 488

Darwin’s On the origin . . . (1859) contained two profound insights whose significance has been subsequently resisted or ignored. One of these insights is slowly gaining recognition in the philosophy of biology, while a further coincidental consequence of his theory is yet to be fully investigated.

First, Darwin naturalized Aristotelian teleology by demonstrating how purpose and design arise in nature in a straightforward causal way without the need to invoke the supernatural, human projection, foresight, or backward causation. Though Darwin himself was ambivalent about purpose in nature, he nevertheless provided a naturalistic account that showed how agency, purpose and design in nature are real, even though they are sometimes described using anthropomorphic language.

Second, and only hinted at by Darwin himself (see quote above), the use of anthropomorphic language in biology is prompted not only by convenience and our natural anthropocentric bias, but also by a lack of technical terminology and an intuitive recognition of our human connection to nature’s mindless biological agency. Much of the controversial anthropomorphic language of biology is not the ‘as if’ talk of cognitive metaphor (a traditional historical assumption) but the ‘like’ talk of biological simile that is grounded in the graded physical features and agential characteristics that are a consequence of descent with modification. Accepting minded human intention as an evolutionary development of mindless biological agency has major philosophical implications.

Life as agency

When we have no words to describe real pre-cognitive agential traits, we resort to the language of human cognition, thus condemning these traits to the figurative world of metaphor

PlantsPeoplePlanet – 2024

This article is one of a series investigating biological agency and its relationship to human agency. These articles are introduced in the article on biological explanation. Much of the discussion revolves around the scientific appreciation and accommodation of real (genetically inherited) but mindless (non-cognitive, ?teleonomic) goal-directedness (agency) that is a universal feature of life. Biological agency is treated as having cognitive and non-cognitive (pre-cognitive) components. The non-cognitive agential traits, as evolutionary precursors to cognitive traits, are referred to here using the general term pre-cognition. While it is currently conventional to treat biological agency as a human creation - the reading of human intention into nature - this website explores the claim that it was non-cognitive biological agency that ‘created’ human bodies and human subjectivity.

The suite of articles on this topic include: What is life? - the crucial role of agency in determining purposes, values, and what it is to be alive; Purpose - the history of the notion of purpose (teleology) including eight modes (claimed sources of purpose) in biology ; Biological agency - an investigtion of the nature of biological agency; Human-talk - the application of human terms, especially cognitive terms, to non-human organisms; Being like-minded - the way our understanding of the minded agency of human intention is grounded in evolutionary characteristics inherited from biological agency; Biological values - the grounding of biological values, including human morality, in organismal behavioral propensities (biological normativity); Evolution of biological agency - the actual evolutionary emergence of human agency out of biological agency; Plant sense and Plant intelligence addressing the rapidly developing research field of pre-cognitive agency in plants.

Describing real but non-cognitive agential biological traits (goal-directed behavior) using the language of human cognition results in cognitive metaphor. This has created profound philosophical and semantic confusion (see human-talk). Formal scientific recognition of pre-cognitive biological agency is, therefore, a combined philosophical, linguistic, and scientific challenge. Though word meanings cannot be changed at will, in science it is possible to refine categories and concepts to better represent the world.[73] It is being increasingly acknowledged that human agency is a limited, specialized, and highly evolved form of more general biological agency. However, without a formally developed and descriptive technical terminology, the agential properties of organisms are frequently described using language conventionally restricted to human agency – essentially the language of human cognition and intentional psychology. Thus, the increasing scientific application of words like ‘agency’, ‘purpose’, ‘cognition’, ‘intelligence’, ‘reason’, ‘memory’, and ‘learning’ across biology is broadening their conventional semantic range to include all organisms, and the treatment of such usage as cognitive metaphor is declining.

For a summary of the findings and claims made in these articles see the evolving article called biological desiderata.

Introduction – Human-talk

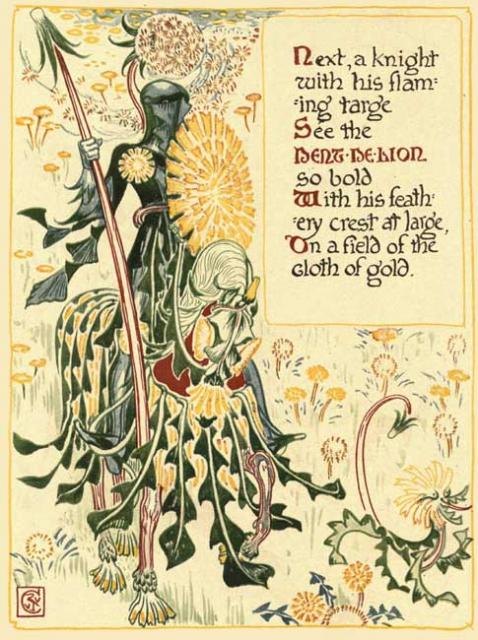

Throughout history we humans have viewed the world through human spectacles, humanizing non-human organisms, objects, and concepts. We find it difficult to resist the urge to anthropomorphize[26] and personify. Literature, art, and religion include many examples of this humanization . . . the human voices and behaviors of Disney cartoon characters like Donald Duck and Yogi Bear, the human-like fallible Gods of Greek mythology, the spirit world of animistic traditional cultures, and so on.

We tend to put ourselves at the center of things, relating to the world by using human concepts. We speak about the ‘eyes’ of potatoes, ‘ears’ of corn, ‘legs’ of tables, and the ‘cruel’ sea – giving plants, animals, and nature in general, human attributes.

For convenience, these various modes of humanization are referred to on this website as human-talk.

Human-talk is the language of humanization – the attribution of human characteristics to non-human organisms, objects, and ideas. In biology we use human-talk most frequently to psychologize adaptive explanations – the cactus having spines to deter herbivores, the spider building its web to catch flies, and so on. Darwin explained how these traits, which seemed to be a consequence of the organism’s purposive intention, arose through the non-purposive operation of natural selection. In other words, that the appearance of purposive conscious intention (a cognitive process) was, in fact, a purposeless mechanical (non-cognitive) process just like all the other physico-chemical processes going on in the world.

There was, however, a problem. Darwin demonstrated that such processes were non-cognitive – plants and spiders do not make conscious decisions – but this did not explain away the goal-directedness of the organisms that were the subjects of this mechanical process. Spiders’ webs and cactus spines undoubtedly achieve real ‘ends’ that are in the world, not in peoples’ minds, and it is this goal-directedness that imbues non-cognitive organisms with a biological agency that is not found in the world of inanimate objects. The absence of conscious intention does not entail the absence of agency. All living organisms, whether cognitive or non-cognitive, are biological agents, but only humans are consciously deliberating biological agents.

In this article, I look critically at the nuanced way that human-talk is (mostly) neither a convenient simplification, as Darwin thought, nor our anthropocentric cognitive bias, as most philosophers and scientists believe today. Instead, it is also fostered by a lack of technical vocabulary and an intuitive recognition of an agential connection between ourselves and all other non-human organisms.

The problem of metaphor

Darwin distilled his thinking about organic descent with modification from a common ancestor into just two words, natural selection. Critics pointed to the anthropomorphic connotations of this expression (the implication that nature ‘selects’ in an intentional human-like way). Darwin countered these accusations by saying that he found it ‘difficult to avoid personifying the word Nature‘ and argued that ‘such metaphorical expressions‘ were harmless and ‘almost necessary for brevity.’ (Darwin 1859, p. 135 cited in Okasha p. 16). Eventually Darwin complied with Alfred Russel Wallace‘s suggestion that he use, instead, Herbert Spencer’s phrase survival of the fittest. The new terminology was duly published in Darwin‘s The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication (1868), and the fifth edition of On the Origin . . . (1869).[10] This is a notable example of the concern about anthropomorphism that has dogged biological science from its earliest days, a concern about the psychologizing of adaptive explanations.

Darwin defended the world-changing thesis of his On the Origin . . . (1859) by using wide-ranging examples of the evolution of physical structures. Later, in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) his interest shifted to more abstract mental phenomena.

Theories about the brain and mind were less amenable to empirical treatment because the mind was obscure and private. Traditional conceptual frameworks explaining the brain and mind were deeply entrenched in religious and academic traditions that resisted scientific investigation.

Another century passed before the evolutionary studies that Darwin’s work had generated made a tentative move from bodies to the brain and cognition as, in the 1970s, evolutionary biology became a mainstream academic discipline in universities, and the new discipline of evolutionary psychology opened up the brain and mind to Darwinian ideas.

Evolutionary psychology recognized that psychological traits are no different from physical traits in the sense that they are evolved adaptations – the functional products of natural selection. Moreover, human nature was not a metaphysical mystery, but the universal set of evolved psychological adaptations developed in response to ancestral environments.

The evolutionary journey from body to brain and mind took about a century, but there is one more step – into the intentional (agential) language and concepts whose meaning, upon close inspection, extends beyond human cognition into the reality of biological evolution and biological agency.

The problem of metaphor remains with us. Are organisms real agents, or are they merely agent-like? Is this a metaphysical question about the nature of the world, or is it just a matter of semantics?

Subjectivity & nature

German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) challenged the 18th century ‘spectator’ view of science (that, as scientists, we are passive observers of the world steadily piecing together an accurate account of reality) with his Copernican Revolution in philosophy. This was an attempt to determine the mental a priori (prior to experience) preconditions that made meaningful human experience possible. He concluded that the human mind is like a lens that structures our experience within the parameters of space and time (the transcendental aesthetic) and provides the logical categories that bind our experience into a unified whole (the transcendental analytic). That is, we see the world not ‘as it really is’, but as it is conveyed to us through the unifying filter of our biology – a human bias that science attempts to minimize.

The philosophical, psychological, and cognitive development of Kant’s ideas led to a subsequent intellectual focus on human subjectivity as the key to our understanding of both scientific inquiry and the world. This human-mind-centred introspection into ‘the preconditions that make experience possible‘ was shaken by Darwin who countered human self-absorption by looking outward into the operations of nature as a whole.

Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling (1775-1854), a largely ignored German Idealist philosopher, best known for his Naturphilosophie has been characterized by contemporary American philosopher Matthew Segall as posing, in a Kantian way, an equally fascinating but neglected question – one that shifts the orientation of our thinking away from ‘self’ (by looking outward rather than inward) by asking: ‘what are the preconditions in nature that make human subjectivity possible?’ This mode of thinking looks to nature (not the human mind) as an originator, source, and creator.

The miracle and beauty of design that is the conscious and self-reflective human brain greatly excels anything ever created by humans. The production of such integrated complexity was clearly not trivial and random but a highly focused and directed form of agency. If nature produced the subjectivity that enables it to reflect on itself, then how does science account for this mindless natural super-agency? What was the process by which matter became aware of itself?

We characterize the agency of natural selection and organisms as a fumbling trial-and-error process. But human subjectivity did not arise out of the brilliance of the human intellect, or the creative imagination of Gods – it emerged out of mindless nature. ‘Evolution is cleverer than you are!‘.[24]

It is philosopher Dan Dennett who likes to quote Orgel’s Second Rule (above). Dennett in his Youtube video From bacteria to Bach and back points out that mind (consciousness, intentionality, understanding) is a recent development, it is an effect, not a cause – we do not live in a mind first, but a matter first, universe. Mindless life is competent without comprehension as, in the course of evolution, meaning and purpose bubbled up from the bottom, not trickled down from the top. What makes humans seem so special is the thinking tools developed in the course of human cultural evolution – this is what is ‘top-down’ – what makes the ‘intelligence’ of brains different from the ‘intelligence’ of termite mounds. Human subjectivity does not account for or validate natural processes: natural processes account for subjectivity. In the Laws (10.903c) Plato declares ‘you perverse fellow . . . you forget that creation is not for your sake; rather you exist for the sake of the universe‘.

This insight can be simplified by pointing out that minded human agency evolved out of mindless biological agency: biological agency is not a metaphorical invention of the human mind, biological agency created the human mind. Agency and purpose were real (objective) properties of life billions of years before the emergence of the human brain.

The Darwinian revolution

Biological structures – like hearts, wings, and eyes – are physical objects open to empirical investigation. But well into the 20th century studies of the brain and mind were considered crude and unscientific speculation about inaccessible internal, and therefore private and unknowable, mental states. The mind was a mysterious spiritual realm whose secrets could only be accessed by religion or philosophy, not science.

There has been a remarkable turnaround as today the brain, mind, consciousness, and artificial intelligence are at the forefront of scientific research – regarded by many as the last major scientific frontier. But the conceptual connections between the language of human intentional psychology and the non-human biological world remain, as yet, underexplored.

We like our ideas to be clear and distinct. Communication is simplified when things are straightforwardly true or false, real or unreal, fact or fiction.

But sometimes physical properties in the real world are not just present or absent, and statements about them true or false. Rather, they exist in nature by degree. We see a rainbow and find it convenient to speak of its discrete colors when, in nature, color is a continuum of wavelengths. While mathematics and physics tend to be about precision and certainty, biology tends to be about generality, gradation, and exceptions.

From an evolutionary perspective, the community of life is what might be called an interrupted organic continuum. Although it is the consequence of a physical continuum in time, we humans find it convenient to discriminate the differences we associate with individual species. We recognize ourselves in apes, much less in whales, and very little in plants. Even so, our common biological heritage means that we actually share many genes with our plant cousins.

Culturally, it seems, we are still coming to terms with the idea of biological continuity. Nowadays we accept that humans are animals. Before Darwin, such a suggestion would have raised eyebrows, partly because it was presumed by most people that humans were a special part of God’s Creation. Humans had souls that needed redemption, animals were not even a part of such a scheme.

Scientifically, we have moved from the desire to establish human exceptionalism (difference) to an acceptance of the more realistic position of our connection to all life (similarity). The idea of plant and animal agency as being continuous with human agency is no longer a heresy.

Prior to Darwin humanity managed daily life, medicine, and biological science, without the notion of nature’s organic continuity and connection. In the Christian world, the similarities and differences of biological species were the discrete creations of God. The scientific account of heritable continuity, of genetic information passed between the generations as shared genes, and over a vast expanse of geological time, all followed after Darwin.

Darwin showed that all organisms and living structures have evolutionary antecedents, and this was a new idea. It meant that a full explanation and understanding of any biological feature must incorporate an evolutionary history of relationships – everything in nature was now connected to everything else both physically, spatially, and temporally.

The combination of Darwinism (1859) and the later replacement of the Steady State theory of the universe with the Big Bang theory (1930s) meant that for the first time, in the early- to mid-20th century, the notion of universal and organic emergence gained a new impetus and significance as science adjusted to the idea of the universe, not as an eternal creation, but as a gradual unfolding of novel elements, materials, structures, properties, and relations. Darwin showed how the particularly complex form of matter that we know as ‘life’, a late arrival in the universe, was a product of descent with modification from a common ancestor. Then physics replaced the former eternal Steady State theory of the universe with a theory of material and stellar evolution originating from the point source of the Big Bang.

A subsequent 20th century chronometric revolution has allowed us to place major universal and biological events within a firm temporal framework. Today, for example, an evolutionary understanding of the organ we call the heart takes us back 600-700 million years to its barely recognizable evolutionary origins as a single-layered tube in tunicates.

These events of the late 19th and early 20th century showed that organs, like human brains, are evolutionarily connected to similar structures in other creatures. Brains and minds are not present or absent in nature, but present by degree, as determined by their evolutionary history.

Before Darwin each species was a unique and immutable creation of God. Darwin made the unpopular claim that humans had emerged in a decidedly undignified way from ape-like ancestors.

The prevailing Aristotelian and Christian understanding of the world and its life forms in Darwin’s day was as a hierarchy of the world’s contents arranged from higher to lower like the rungs of a ladder, surmounted by humans and eclipsed only by God. Darwin represented life as a tree on which humans were not the single ultimate goal of evolution as implied by the ladder metaphor. Instead, he proposed that the selective interaction between organisms and their environments had produced many physical solutions with humans just one of these, poised at the tip of just one branch of the vast tree of life.

The cognitive continuum

We have accepted the idea of humanity being part of an evolutionary continuum, but our human self-interest and anthropocentrism find it difficult to accept the idea of mental attributes and human agency having properties that relate to our non-cognitive biological ancestry. The intellectual challenge is to accept that consciousness, intelligence, and mental phenomena generated by brains and neural systems share general ‘cognitive’ principles with non-cognitive organisms – not just those with rudimentary nervous systems. These shared ‘cognition-like’ properties arose because cognition is an elaborate and specialized evolutionary solution to problems faced by all living organisms. That is, cognition evolved as one biological solution to universal biological imperatives.

Among these universal imperatives is the need to gather and process information about conditions of existence, and to generate appropriate adaptive responses based on this processed information. The infinite variety of structures, processes, and behaviors, especially sensory ones, assist organisms in this process. While we recognize cognitive processes such as perception, memory, learning, and decision-making as being critical for our human agency and existence these processes evolved out of non-cognitive antecedents that were addressing the same general problems impacting on their survival and reproductive success.

We assume that we eat because we are hungry and enjoy food smells and tastes, and that we have sex for emotional comfort, physical enjoyment, and the pleasure of orgasm. But this is what our evolved cognition tells us: biologically we eat to survive and have sex to perpetuate our kind . . . but being cognitive organisms, non-cognitive biology has given us cognitive rewards to achieve its non-cognitive ends. (sort out the anthropomorphism here!)

Biological agency is either denied altogether or measured in human terms as being only agent-like because the only real goals in nature are the goals of human intention. But, our mental faculties are cognitive evolutionary elaborations of non-cognitive (pre-cognitive) conditions and goals and, in this sense, the cognitive goals of human agency are grounded in, and therefore subordinate to, the goals of biological agency. Biological agency is not a creation of our minds; our minds are creations of biological agency.

This sense of cognition extends beyond traditional notions of intelligence and consciousness to include a broader set of adaptive mechanisms for processing information and adapting to general conditions. In this view, plants exhibit forms of cognition through their ability to perceive and integrate environmental cues, adjusting their growth and development accordingly.

For many people, the concept of plant cognition crosses too many semantic and other boundaries; it is therefore unacceptable. It certainly goes against current usage. The alternative appears to be a business-as-usual denial of both real biological agency and the real evolutionary principles that connect the pre-cognitive to the cognitive.

Anthropomorphism

What are the reasons why we anthropomorphize nature? Do we humanize non-human behavior in the same way that we humanize non-human body parts . . . that is, are the conventions of physical and mental humanization different? And how do general anthropomorphic language, and the more specific mental language of the intentional idiom, relate to the literary device called metaphor?

Our understanding of anthropomorphism (human-talk) in biology has been plagued by two major and long-standing historical difficulties: first, our insistence that agency be exclusively associated with cognitive phenomena; second, the historical tradition of describing empirical phenomena through the medium of a literary device.

Agency & mindedness

All organisms demonstrate real biological agency as the ultimate behavioral orientation or propensity to survive, reproduce, adapt, and evolve. Denying this agency – as we do for pre-cognitive organisms – condemns them to the same mode of existence as inanimate objects while, at the same time, ignoring the evolutionary continuity of the entire community of life.

While all organisms, both cognitive and pre-cognitive, demonstrate biological agency, only humans have advanced cognitive faculties. However, there are many shared characteristics of cognition resulting from common ancestry so it is hardly surprising that pre-cognitive biological agency is often described using cognitive language.

So, faced with real but pre-cognitive agency we resort to the cognitive language of human agency. That is, we describe real pre-cognitive biological agency using cognitive language, and this results in cognitive metaphor. We then mistakenly assume that the unreality of the metaphor entails the unreality of biological agency.

This fails to distinguish between agency and mindedness. While all organisms demonstrate agency, only humans demonstrate intentional and deliberative agency. Attributing cognitive faculties to mindless organisms is clearly metaphor, but this does not mean that the agency of non-minded organisms is also metaphor.

The use of cognitive metaphor is a clumsy attempt to draw attention to the real biological agency that unites all living organisms. The desire to indicate the shared features of biological agency is interpreted literally as the projection of cognitive faculties onto mindless organisms. The intent of the language is to draw attention to non-cognitive but agential behavior, and it does this in a clumsy way by using cognitive metaphor.

The purpose inherent in non-cognitive agential behavior does not go away simply because it is inadequately described using cognitive metaphor. Does a prosthetic leg have purpose because it is a creation of human deliberation, while a spider’s leg only has purpose in a metaphorical sense?

Because we have direct and conscious experience of our own intentional agency, and nature does not have conscious awareness of its own biological agency, we conflate nature’s no awareness with no agency. We mistakenly assume that biological agency, being non-cognitive, is only ‘as if’ agency. This is what philosopher Dan Dennett calls a ‘strange inversion of reasoning’.

When we say a plant wants water, we are not trying to convey our scientific belief that plants have cognitive faculties, we are indicating that without water the plant will be unable to survive, reproduce, and flourish. We are drawing attention to the evolutionarily connected agential characteristics of biological agency that are shared by all organisms.

There is agency and purpose in all goal-directed behavior. Both humans and plants quickly die without water, although only cognitive organisms feel thirst.

Literary devices

So, when we use anthropomorphic language (human-talk) we are usually drawing attention to the biological agency (likeness due to common ancestry) that we share with other organisms, not suggesting that non-cognitive organisms have cognitive faculties like ours.

Once this confusion is accepted, it becomes immediately apparent that the use of metaphor (or any literary device) is inappropriate for comparing likenesses that are a result of shared evolutionary history. This likeness is neither ‘literal’ (which suggests that e.g. plants have cognitive faculties) nor ‘as if’ (figurative) because the similarity is grounded in the reality of evolutionary gradation.

Physical & mental

Grand concepts like consciousness, knowledge, value, reason, purpose, and agency, are almost universally regarded as elements of an impregnable human cognitive domain. But, just as uniquely human eyes and hearts have non-human evolutionary antecedents, so our cognitive faculties – and concepts – also reach back into our non-human and non-cognitive evolutionary history.

This is a difficult thesis to defend because the distinction between the cognitive and non-cognitive seems clear-cut and undeniable – self-evident by word meaning alone. If knowledge is something that exists in a mind, then it cannot exist in a plant because plants don’t have minds.

An investigation of human-talk and biological agency suggests a more nuanced conclusion.

Biological gradation

Does a rock ‘know’, ‘value’, or ‘reason’? It might be possible to stretch the meaning of these words to eke out some connection but, for most people, such a step goes way too far.

But what about non-cognitive organisms, can they ‘know’, ‘value’, or ‘reason’?

Our first reaction is probably the same. A plant cannot ‘know’ any more than a rock can ‘know’.

But consider how genetic information passes between living organisms (knowledge), how the goal-directed behaviour of all non-cognitive organisms gives them a distinctive behavioural orientation (normativity, agency), and how both long-term natural selection and short-term behaviour of all organisms is a process of constant adaptation to conditions of existence as repetitive ‘self-correction’ (reason).

None of these processes are cognitive processes, but they are a step in that direction – they are ‘like’ cognitive processes in an evolutionary sense of ‘like’ that makes organisms very different from rocks.

Why use human-talk?

If human-talk is the source of so many problems then why don’t we avoid it altogether?

Do we really need to speak of ‘the cruel sea’ or a ‘clever idea’, and say that a river ‘yearns’ for the coast? In biology, wouldn’t it be both simpler and more scientific to avoid saying that the cuckoo ‘deceives’ its host; that natural selection ‘chooses’ or ‘favors’ one outcome over another; that the ‘purpose’ of eyes is to see; that the snail ‘wants’ to avoid the light and sun; and that the spider ‘knows’ how to weave its web?

As a potential source of scientific error, confusion, and biological insight, surprisingly little research has focused on the analogical reasoning[5] of human-talk.

Likeness

Though there are several reasons why we use human-talk (see below), it is, in a broad sense, a way of drawing attention to likeness.

Likeness comes in many guises. Human-talk makes comparisons between humans and non-humans using various criteria of comparison. So, the criterion of likeness or similarity might relate to structure, function, appearance, colour, or a myriad of other properties and their combinations. Similarities range from a real empirically verifiable connection to whatever fantastical likeness we might care to imagine. It is this multiplicity of likenesses that is exploited by literary devices such as metaphor, simile, personification, and so on.

Our interest is scientific, and this begs the question as to how genuine (rather than imaginary) organic likeness is established.

Biological likeness

Evolution provides us with our best scientific account of organic likeness because it establishes physical (genetic) continuity of relationships over time. When two living objects are likened to one another in an evolutionary context then we know that there must be a physical connection in time, no matter how distant or how small.

Science overcomes conceptual fuzziness, generality (semantic range), abstraction, and openness to interpretation, by using clear, simple, and closely defined technical terms.

So, to differentiate, say, the legs of humans from those of spiders (because they evolved differently and are differently constructed) precise technical terms can be coined.[14] But this precision does not eliminate the concurrent need for the abstraction of grounding concepts. Even if all kinds of legs were given scientific names, we would still need the general notion ‘leg’ (the shared concept of the group).

To study the evolution of any biological feature two critical sets of characters are needed: those that define individuals – that make them unique; and those that are shared with others as a necessary consequence of descent with modification from a common ancestor. So, there are many vertebrate species, each with their own unique features (unique), but all have backbones (shared).

This simultaneous consideration of similarity and difference (the shared and the unique), as the general and particular, [22] is a powerful way of establishing evolutionary context and it is neatly captured in binomial nomenclature. So, for example, in the Latin name Homo sapiens, Homo denotes general similarity, the shared characters of the genus Homo, while sapiens indicates points of difference, the unique characteristics of a particular species. The name Homo is like a broad conceptual stage, a common ground on which related individuals, each with their own unique characteristics, can play – like Homo erectus, Homo ludens, Homo heidelbergensis etc.

So, to establish evolutionary context of any organism, structure, or concept we need both shared or grounding characteristics, and emergent characteristics that express individual variations on this grounding theme.

From now on in this article, concepts expressing shared characters, and the abstraction of generality, will be called grounding concepts while their more specific counterparts, or instantiations, will be called emergent concepts.

Principle – to establish the evolutionary context of any organism, structure, or concept, two sets of characters must be considered: those that are shared with its relations (grounding characteristics), and those that are unique to the item under investigation (emergent characteristics)

There are many reasons why we humanize nature, they include: literary flourish, cognitive bias, convenience, lack of technical vocabulary, and our empathic identification with, and connection to, biological agency.

Literary flourish

From a literary point of view, we enjoy using our creative imagination to produce engaging and colorful prose. This brings the world closer to ourselves, to our human way of seeing things, and we can do this by using the literary devices of anthropomorphism, personification, human similes, and human metaphors.

Personification is widely expressed in mythology, religion, fables, and storytelling. It is hardly surprising that the supernatural world of Gods and spirits of both past and present has taken on human forms and behaviours. In prehistory humans imbued all of nature with supernatural, often personified, agency.[12] . . . like the thundering voices of angry Gods coming from the sky during a rainstorm. Forests, streams, mountains, trees, and landscapes were populated by spirits, demons, and supernatural human-like animistic forces of many kinds. Gradually, over time, the numbers of these supernatural beings diminished, and supernatural belief focused more on Gods (generally interpreted as men and women). At first there were many (polytheism) but, eventually, and over much of the world, just one (monotheism). Gradually Gods too became more distant. In ancient Greece the Gods, who lived a human-like existence replete with the same follies and foibles as human-beings, lived high above the world at the tip of Mount Olympus. In later civilizations these personifications departed this world altogether, ascending into the sky to become ethereal, eternal, and ineffable . . . and, eventually, completely dissociated from space and time.

Though acceptable as a literary device, human-talk in biology is usually regarded as a misrepresentation of reality, taking the form of scientific ‘as if’ metaphor.[13] Scientifically, we need to grasp the world as it is, not as our imaginations would have it. Treated as metaphor, biological anthropomorphism is of heuristic value, at best.

Cognitive bias

When concepts become difficult to express we tend to personalize them, because that makes them more user-friendly.

Human-talk conforms to our natural anthropocentric cognitive bias. We see the world from a human perspective – how could it be otherwise? Our humanization of the world may be as blatant as our personification of animals (Yogi Bear, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck), or as subtle as the insinuation of human perceptions into science (the observer effect, our human sense of space, time, scale, and so on).

Lack of technical terms

In biological science the temptation to use human-talk is also motivated by a lack of technical vocabulary.

So, for example, we have the general concept ‘eye’ as an organ of vision (with the human ‘eye’ being, as it were, a reference point). Then, to clearly distinguish between the multitude of eye-like structures that exist in nature we coin technical words with precise scientific meanings, the degree of discrimination between each depending on scientific requirements (e.g. simple, compound, eye-spots, pit eyes, ocelli, ommatidia, and so on). If there is no formal scientific description based on the structure of eyes themselves then we resort to designations like ‘dog eyes’, ‘insect eyes’, and so on, but this potentially decreases the scientific precision of meaning.

When we study an amoeba, though it is vastly different from humans in physical structure, we nevertheless intuitively recognize in its agential behaviour similarities to our own behaviour. It will move away from toxic surroundings and predators, it reproduces, it is attracted to sources of food, and so on. There is no agential vocabulary for these behavioural traits as they exist uniquely in amoeba. Without these amoeba-specific behavioural terms and, with our anthropocentric cognitive bias, we therefore resort to anthropomorphic human-talk. We speak of amoeba’s ‘preferences’, ‘self-regulation’, ‘behaviour’, ‘strategies’, ‘self-preservation’, and in this way we indicate the similarity of human and amoeboid agential behaviour, using the language of cognitive association.

In this instance the human-talk is telling us that amoeba behaviour is like human behaviour, it is not expressing a metaphorical (figurative) similarity, but a similarity that is grounded in the real agential properties that are shared by all organisms as expressed in the biological axiom.

Each species has its own unique way of expressing agential traits (humans express some of them in a notably minded way) and, ideally, each could be uniquely identified using appropriate scientific terms. We do not have a scientific glossary of such terms and so, instead, we resort to human-talk, thus opening the door to accusations of biological metaphor and therefore figurative, not real, science.

If we believe that human agency evolved out of biological agency then we need a bridge of language and meaning that merges functional adaptation with human intention because the semantics of human intentional psychology has yet to catch up with the evolutionary theory on which it is based.

Principle – without the technical language to uniquely circumscribe the agency of each species we resort to the language we use for our most familiar agency – human agency. This opens the door to the accusation of metaphor

At present, the use of human-talk indicates a lack of technical vocabulary. This situation also occurred in the history of structural biology which subsequently built up its technical terms.

Naturalizing human-talk in this way is an unlikely prospect. A more probable approach would be to naturalize human-talk by acknowledging the reality of evolutionary connection and, by recognizing that both physical and mental characteristics have evolutionary precursors. Either way, this will take a long time.

Convenience

We use human-talk, in part, out of laziness or, as Darwin expressed it, ‘for brevity’. Transposing the human-talk of the examples given at the head of this article into more objective language would be a tedious and time-consuming process. For example, converting the human-talk of ‘The spider knows how to build its web‘ into non-anthropomorphic biological language entails a long causal explanation involving genetics and evolutionary history.

Agential connection

We intuitively recognize our evolutionary connection to other organisms, even when that evolutionary connection is extremely distant. But it is the agential characteristics of other organisms that we recognize rather than their physical features. We do not have such a connection to the inanimate world and the dead. We can hardly empathize with plants based on similarity of physical appearance but we certainly accept that a plant can ‘want’ or ‘need’ water in a much more meaningful sense than a river ‘wanting’ to reach the sea. Moreover, this agential connection is real, not metaphorical, because it is founded on the genetics of common ancestry. Plants and non-human organisms may not have minds, but they display the biological agency (biological axiom) of all living organisms, including humans.

The characteristics that make humans unique and special are built on a foundation of shared structures, properties, and relations that can be traced back to the dawn of life on Earth – connections that are built into our genetics, biochemical processes, behavioural traits, and the single feature that unites us most strongly with the community of life – our shared agency.

Because we humans share the ultimate values of all living organisms (the biological axiom) we intuitively identify with other creatures in a manner that is different from the way we relate to rocks. This is part of our accounting for human-talk and the anthropomorphic bias. It is why we can relate to the life of a bird, or even a plant, in a way that we cannot relate to a rock. We intuitively recognize our evolutionary connection to the community of life, its agency, and the biological normativity expressed in the biological axiom. There are many insights to be gained when we acknowledge the biological grounding states that makes real the language of human intentional psychology as it is applied to nature (see human-talk).

With increase in material complexity there is a corresponding increase in complexity of our conceptualization of the relationship of cause to effect. In the inanimate world this relationship expresses the impersonal ordering of matter by physical constants. In mindless nature there is the additional ordering of organic matter causes produce effects that are ‘for the better’. These are short-term and long-term behaviour, processes, and structures (adaptations) that promote the survival, reproduction, and flourishing of organisms. These are ordering effects that, in human-talk, are ‘beneficial’ to the organism. Humans then manifest self-correction by conscious deliberation.

There is a continuum across the natural world running from inorganic cause and effect to organic purpose, agency, and normativity.

Principle – agency is expressed in the pursuit of goals, a characteristic that unites all life (see the biological axiom). Though all life manifests mindless goals, humans in addition, express minded intentions.

Metaphor

Metaphors, we have realized in the last few decades, are much more than literary flourish. Our language is saturated with metaphor which serves as an indispensable part of our cognition, facilitating concept formation and communication. This is especially important in scientific communication because it can shed light on obscure ideas. Scientific metaphors can, for example, weaken or uphold scientific paradigms.[7][8][9]

More precisely, though, metaphors are figures of speech that compare things (the relata) by drawing attention to similarities, often in a colourful way. Most importantly, and by both definition and common usage, these similarities are not there in reality, they are figurative. Metaphors are ‘nonliteral comparisons in which a word or phrase from one domain of experience is applied to another domain’ [2]

In simple terms, metaphors are ‘as if’ language, and in science the word ‘metaphor’ signals ‘figurative’ or, more specifically, ‘not real’.

Metaphors are stronger than similes. Similes convey the similarity of relata by using words such as ‘like’ or ‘as’, while metaphors usually compare by saying something ‘is’ something else. So, ‘your lips are like a red red rose’ is a simile, while metaphors would include ‘all the world’s a stage’, ‘time is money’, and ‘love is hell’. Hypocatastasis deals briefly with metaphorical similarity by naming only one of the relata.

‘You are like a rat’ – simile

‘You are a rat’ – metaphor

‘Rat!’ – hypocatastasis

Clear-cut examples like this point directly to the unreality of the relationship expressed by the metaphor (in this case, the fact that humans are not rats).

When considering biological metaphors, it helps to compare metaphors of the body and metaphors of the mind – the human-talk that we use to describe non-human physical structures (non-cognitive human-talk), and the human-talk language of mental states that we use to describe non-human biological agency (cognitive human-talk), sometimes referred to as cognitive metaphor.

Principle – metaphors use ‘as if’ (figurative) language, and in science the word ‘metaphor’ signals ‘not real’.

Non-cognitive human-talk

Human-talk, when used to describe non-human organisms, takes many forms. There is cognitive metaphor when, for example, we say that a plant wants a drink because we are investing a plant with human-like cognitive faculties. But there are plenty of metaphors in biology that liken a structure from one domain of biology to a structure in another domain using non-cognitive relata. So, for example, we talk of tree ‘limbs’, ‘ears’ of corn, and the ‘eyes’ of potatoes.

Straightforward examples of non-cognitive metaphors like these are swamped by the many other non-cognitive forms of human-talk used to describe non-human organisms. These are so abundant, and so subtle, that it becomes extremely difficult to interpret what we might count as human-talk . . . what is metaphor, and what is some other figure of speech. We use metaphors so frequently that we often don’t realize that they are metaphors. These hidden metaphors are known (metaphorically) as ‘dead’ metaphors e.g. car ‘body’ and tree ‘trunk’.

The word ‘leg’ will illustrate this point.

Following our anthropocentric cognitive bias, almost any biological organs used for standing or locomotion are loosely referred to as ‘legs’. This usage even extends to the inanimate world when we speak of the ‘legs’ of tables and chairs. In these instances, the word ‘leg’ is being used in a casual, non-scientific and non-technical way to convey function. When used in this broad sense the word ‘leg’ circumscribes a multitude of objects, structures, and functions and in so doing it gathers abstraction to assume what can be called a wide semantic range . Perhaps when we talk of a chair leg we might say we are using metaphor, but what about the legs of a spider . . . is that metaphor?

There are many human words used in this general way. They include: physical structures (‘body’, ‘head’, ‘leg’, ‘arm’, ‘foot’ etc.); actions (‘eating’, ‘sitting’, ‘running’, ‘behaviour’, ‘looking’); and various characteristics and properties (‘sex’, ‘male’, ‘female’), and so on.

Words like these used casually and with a wide semantic range can be interpreted in many ways. So, when we speak of the ‘arms’ of an octopus, the likeness to human arms may be referring to structure, function, a combination of these – or maybe something else.

The word ‘body’ has a semantic range that encompasses any creature in the animal kingdom (and even some objects that are not e.g. car body). There is usually no philosophical or scientific objection to such usage because the word ‘body’ is being used in a generalized, abstract, informal, and non-technical way.

Is it correct to describe such usage as metaphor?

Well, an insect ‘head’ is hardly like a human ‘head’. But in cases like this we are not claiming that an insect head is the same as a human head, but that it shares a likeness. In this instance ‘head’ means, more or less, ‘the part on top of the body’. If a literary comparison is to be made here then the comparison between human and insect ‘heads’ is a simile, not metaphor. To insist that ‘head’ is being used here as metaphor simply mistakes the particular criterion of likeness that is being used, the things that are being compared. The implied assertion of likeness relates to position, not biological identity. Scientists and non-scientists alike accept unreservedly that mice have ‘heads’ and ‘legs’, that they ‘run’ and ‘eat’. . . and so forth. To claim that these words are being used as metaphors misunderstands their role in communication.

Could cognitive metaphor be like this? Is the aim of the language of conscious mental intentions applied to non-human organisms to convey something more general than human intent? When we say that bats like the dark, aren’t we drawing attention to a particular agential behavioural characteristic of bats rather than insisting that they have human mental faculties? Undoubtedly the language is cognitive metaphor (figurative i.e. unreal) but the underlying behaviour that it is attempting to describe is real.

A few more cases will illustrate what is going on with non-cognitive human-talk.

The word ‘self’ sounds like a ‘human’ word (an amoeba is hardly a ‘self’ in the way that you and I are ‘selves’) and yet the word ‘self’ is applied to many organisms. Biology is full of expressions like ‘self-replication’, ‘self-organization’, and ‘self-regulation’. But again, such usage does not flag the selfhood we associate with our individual human identity and awareness, rather, it is a simple acknowledgement of individual biological agency, the fact that organisms and some other structures have a degree of autonomy, that they can act as independent units.

What about the word ‘behaviour’ in relation to non-human things? Are we at our scientific best when we speak of the ‘behaviour’ of plants. We even speak of the behaviour of molecules? Again, the word ‘behaviour’ is being used here in such a broad sense that it is mistaken to suggest its use be scientifically confined to humans only.

The categories ‘male’ and ‘female’ are also almost universal across biology, including the world of plants. In a casual sense we are drawing attention to a foundational distinction in biology. But male and female plants (and their male and female organs) bear no physical resemblance to male and female humans and their sex organs. Once again it is clear that such terms are not making claims of identity with humans. We are aware here that the word ‘sex’ has a wide semantic range and that, in biological terms, it may be instantiated through many evolutionarily graded physical forms.[18]

In biological evolution new physical features are built on a pre-existing structural foundation. Is it possible that the language of human intentional psychology applied to non-human organisms is part of a historical linguistic tradition – our human way of conveying biological agency – an agency grounded in mindless organisms and implying a biological connection (which we now know to be an evolutionary connection) that our scientific predecessors found unpalatable and therefore unacceptable?

Principle – the human-talk of non-cognitive biology is accepted scientifically because of its uncontroversial semantic range, abstraction, and openness to interpretation (grounding concept). This generalized application rules out its use as metaphor

Scientific metaphor

Is it possible to confidently determine whether human-talk in biology is being used as metaphor, simile, or in some other way? Can we discriminate, with certainty, between scientific simile and scientific metaphor?

We might, for example, use the words ‘wing’ and ‘leg’ in a non-scientific and functional sense to indicate an organ of aerial locomotion (including, say, the ‘wings’ on the seed of a maple tree) or ‘leg’ to mean an organ of land locomotion, and ‘head’ in a positional sense to indicate a structure on top of an animal body. When used in these casual ways ‘wing’, ‘leg’ and ‘head’ act as biological grounding concepts with many senses and literary forms.

Biology can, however, insist on the strict scientific (emergent) usage of the term ‘wing’ defined from a structural evolutionary perspective since other perspectives (like those of function) are poor indicators of evolutionary relationship.

When using terms in this precise evolutionary sense a distinction can be made, for example, between the wings of butterflies and the wings of birds. These two kinds of wings, though functionally similar, are evolutionarily unrelated and, to recognize this fact, they are called analogues. In literary terms the word ‘wing’, as used in this context, becomes akin to a simile or metaphor. In contrast, wings of evolutionarily closely related organisms are called homologues or homologies (‘wing’ as used here has a precise scientific-evolutionary meaning).

Likeness based on homology is scientifically sound, but when based on other factors it is less secure. Homologies can have the same evolutionary origin but different function, so the dissimilar wings of bats and paddles of whales are homologous as are the ‘legs’ of humans, deer, and bats (which are based on a common ground-plan, the pentadactyl limb). When there is precision of meaning, confusion over what constitutes metaphor disappears.

The four major flower parts – carpels, stamens, petals, and sepals – are homologous because they are all evolutionarily derived from leaves. In an evolutionary sense they are all leaves (shared grounding concept), but with their own unique additional characteristics (emergent concepts). A simple grounding idea (leaf), while retaining its evolutionary significance has, in the course of evolution, become structurally differentiated into new forms. In evolutionary terms, then, we can legitimately make the apparently absurd claim that a petal is a leaf. This example illustrates the potential conflation of grounding and emergent concepts. In a similar way, human agency is a uniquely specialized form of biological agency – it retains the shared characteristics of biological agency while at the same time displaying its own unique form of these characteristics.

A few further examples will illustrate the way we can confuse or conflate grounding and emergent concepts and therefore throw into question what is, or is not, metaphor.

In strict scientific (evolutionary) terms, the avocado is not a pear (it is genus Persea, not genus Pyrus), the koala is not a bear (the koala is not in the family Ursidae) and, contrary to popular usage, the tomato is, botanically, a fruit.

The cognitive dissonance we experience when confronting such examples relates to confusion over the kind of likeness we are addressing – is it the likeness of grounding criteria (i.e. an avocado having the same general shape and appearance as the domestic pear; the koala having the same cuddly appeal as a teddy bear), or is it the emergent concept (i.e. a scientifically precisely defined emergent concept)? If we accept the emergent concept of avocado then ‘pear’ is simply incorrect, there is no real connection, only a figurative likeness, and it is therefore being used as metaphor. If we accept the grounding concept then attention is being drawn to a more general likeness (its shape and general appearance) in which case simile is the more appropriate literary designation since this is not a figurative similarity, although the likeness is not based in scientific connection.

These examples have illustrated three kinds of likeness: those that are soundly evolutionarily based or literal (leaves and flower parts; legs of deer, humans and bats; wings of bats and paddles of whales); those that are figurative or metaphorical (avocado pear and koala bear when used as emergent concepts); and likenesses based on other similarity criteria (avocado pear and koala bear used as grounding concepts) which is more akin to simile.

Distinguishing between such likenesses clearly depends on context and individual interpretation.

So how does this relate to the cognitive metaphor we encounter so often in biology?

Principle – contextual analysis can discriminate criteria of likeness including distinctions between scientific, metaphorical, and other criteria of likeness

Principle – the language of biological science takes on the meaning implied by the latest scientifically accepted research.

Principle – we draw a heavy line of distinction between biological agency and human agency; between the mindless and the minded

The statement ‘This plant wants water’ is clearly a cognitive metaphor . . . but is it unreal nonsense like saying ‘This moon wants a spaceship’? Cactus spines do not consciously deter, but they certainly contribute to survival, reproduction, and flourishing. ‘Goals’, ‘missions’, ‘purposes’, even ‘reasons’, may be regarded as a form of human-talk. After all, how can a plant possibly have a mission – that is ridiculous? Even the ‘reasons’ for its structures and behaviour seem qualitatively different from human ‘reasons’. When we are intellectually off-guard we refer to biological agency using the word ‘purpose’ but, by convention, we avoid the embarrassment of attributing conscious intention to mindless organisms, preferring the word ‘function’. A prosthetic leg has a purpose because it was designed with conscious intention, but we dare not say that an insect leg has a purpose . . . only a function: that it is a functional adaptation.

Cognitive human-talk

Biology has, on the whole, accepted the non-cognitive humanization of physical structures and activities because its concepts are generalized (they have a broad semantic range, are abstract, and open to interpretation). That is, the criteria of ‘likeness’ used to compare relata are accepted as being so diverse and generalized (structure, function, appearance etc.) that the strict scientific comparison needed to confirm or deny the use of metaphor is no longer appropriate. So, for example, objecting to the use of the term insect ‘body’ on the grounds that this is metaphor is inappropriate and carries no force.

Controversy over the use of anthropomorphism in biology has focused mainly on the attribution of minded states to non-human organisms using the language of human intentional psychology. Among these words are: ‘want’, ‘learn’, ‘remember’, ‘know’, ‘select’, ‘value’, ‘choose’, ‘prefer’, and ‘reason’, as well as ‘purpose’, ‘agency’, ‘interest’, and ‘strategy’. These are all words we associate with human agency.

Although all organisms exhibit biological agency (behaviour grounded in the goals of the biological axiom) there is no generalized vocabulary for this agency as a whole. Indeed, each species expresses its agency in its own way depending on its uniquely defining features. The language of intentional psychology serves as a technical vocabulary for one species only, the minded species Homo sapiens.

It must be considered possible that the language of human intentional psychology is being used in the same way as the humanizing language of non-cognitive humanization. That is, it is being used (or intended) in a generalized (grounding concept, biological agency) sense – rather than in the strict sense of human intention (emergent concept, human agency).

The objection to such a claim is obvious. How can the mindless engage in mental activity? Clearly a plant, which has no nervous system, could not possibly ‘want’, ‘anticipate’, ‘remember’, ‘know’, or ‘choose’. Mind words are scientifically inappropriate to describe the activity of mindless organisms. And, if there is no real relationship between the minded and the mindless the the comparison is non-scientific (unreal, figurative) and therefore a straightforward case of cognitive metaphor.

But let’s look more closely at agential thinking in general and how it relates to the specific instance of human intentionality.

To understand the place of humans within the community of life we need to know not only the emergent characteristics that uniquely define our species, that make us special[16] but also the characteristics that we share with other organisms. But, while the principle of shared and unique characters is easy to follow when describing the evolution of physical structures, it is not so straightforward when applied to general concepts and the language of human cognition.

This idea will be explored in more detail later, but for the time-being consider that when Darwin used the expression ‘natural selection’ (which Darwin himself treated as a form of cognitive metaphor) he was likely inferring, not ‘selection’ in the restricted sense of a deliberate and conscious human choice (a minded emergent concept), but the more general notion of a mindless process of filtering or constraint that limited possible outcomes (a mindless grounding concept) – which was, in the specific case of natural selection, the mindless process of differential reproduction. This interpretation of Darwin’s intentions is reinforced by his use of the preceding word ‘natural’.

To follow the implications of grounding and emergent ideas when applied to cognitive concepts we must delve deeper into the connection between human-talk and agency.

Cognitive metaphor

Human-talk is usually encountered as cognitive metaphor – the attribution of mental states such as thoughts, feelings, and desires to non-cognitive organisms and objects. We do this using the language of human intentional psychology. We say that a plant wants water, or that a spider builds its web in order to catch flies, the cuckoo deceives the mudlark, and cacti have spines to deter herbivores.

Using the logic of metaphor – where one of the objects being compared is always figurative (not real) – we reasonably conclude that it is only as if organisms have human-like needs, feelings, and intentions.[27]

However, on closer examination, it is clear that the language of cognitive metaphor is not trying to make the literal assertion that non-cognitive organisms have cognitive faculties; it is trying to convey the similarity between the agency we associate with human intention, and the similar kind of agency we associate with goal-directed but non-cognitive organisms. We intuitively recognize that all living organisms share the propensity to survive, reproduce, adapt, and evolve. This is a universal form of biological agency.

Our use of the agential language of cognitive metaphor is a clumsy attempt to capture the real and universal characteristics of biological agency that humans share with all organisms. The use of cognitive metaphor draws attention to a real sharing of non-cognitive biological goals, not a fictitious meeting of minds.

Cognitive metaphor attempts to communicate the shared features of biological agency; it does not insist that non-cognitive organisms demonstrate the cognitive properties we associate with human agency. Paradoxically, when we say a plant ‘wants’ water we are not insisting that plants have human-like cognitive faculties (human agency), instead, we are acknowledging that plants, in common with humans, depend on water for their survival (biological agency).

This characterization of cognitive metaphor makes a distinction between biological agency in general and human agency in particular. Biological agency is the goal-directed agency that is shared by all living organisms and it exists in both cognitive and non-cognitive forms. When viewed in this way it is clear that human agency evolved out of biological agency and shares its ultimate goals; it is a cognitive form of biological agency and, as a sub-set of biological agency it shares many of biological agency’s non-cognitive characteristics.

It is important to recognize that human agency has both cognitive and non-cognitive (instinctive, innate) components.

Agency

We understand agency from the perspective of human agency, from our own conscious intentions and deliberations: this is a natural cognitive bias. This human bias means that we can be blind to the agency that is all around us in nature.

All organisms display goal-directed behaviour, and where there are goals there is agency and purpose. This agency is what distinguishes life from the inanimate and the dead. For convenience, it is referred to here as biological agency.

The ultimate source of goal-directed behaviour – of life’s agency and purpose – is its propensity to survive, reproduce, and flourish. This is our most succinct statement of the universal preconditions for organic agential existence – a statement referred to on this web site as the biological axiom. It is a precondition for life that is as apt for a microbe or mushroom as it is for a human.

We describe human agency, which is the uniquely human expression of biological agency, by using the minded language of intentional psychology. However, we lack the technical language needed to describe the unique (mostly mindless) forms of agency expressed by each and every other individual species. To overcome this deficiency, we resort to the inappropriate use of human intentional language, which is then (reasonably) treated scientifically as cognitive metaphor. That is, we treat non-human organisms, not as agents, but as agent-like (where ‘like’ implies the figurative similarity of metaphor, not the potentially real likeness of simile).

Principle – human agency is a specialized (minded) evolutionary development of (mindless) biological agency

Agential thinking

Resistance to the use of cognitive human-talk applied to non-human organisms stems mainly from the perceived impenetrable gulf between the minded and the mindless which is assumed to establish the difference between real agents and unreal (metaphorical) agent-like things.

Even so, intentionality (the ‘aboutness’ of our human mental experience – the way it is always focused on, or directed towards, some object or situation) resembles the goal-directedness and agential activity exhibited by all organisms. It is this similarity that, at least in part, prompts the use of cognitive human-talk.

Philosopher Dan Dennett has approached agential likeness in nature by assuming what he calls the intentional stance. He says:

‘Here is how it works: first you decide to treat the object whose behavior is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in most instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do.’

Daniel Dennett, The Intentional Stance, p. 17.

Dennett points out that, regardless of the language being used, if this method works as a form of intentional system analysis then it is not as if the system is intentional, it actually is intentional.

Dennett’s case can also be made by pointing out that if we consider intentionality as existing in nature by degree with human agency a subspecies of universal biological agency (not biological agency as an invention of human agency) then we not only see its presence within non-conscious organisms (albeit mindlessly, unconsciously, and in crude form) but also in real and non-metaphorical ways. We then understand how intentionality is grounded in the goal-directed agency of the biological axiom.

But to say a plant ‘wants’ water is surely nonsense. How can we possibly accept this?

We can accept a technical definition of intentionality that relates strictly to conscious human minds (emergent concept) while at the same time recognizing its origins in the generalized simile-like comparison with the goal-directed agency of all organisms as expressed in the biological axiom (grounding concept). Thus, we see in nature a general intentionality (goal-directedness) that grounds the emergent concept of intentionality as it is manifest in human intentional psychology. The similarity of non-human organismic agency and human agency is not metaphorical (figurative), it is grounded in evolutionary history and the biological axiom.

In other words, agential behaviour is a universal property of the community of life with human intentionality just one specialist evolutionary outcome, and all agency is grounded in the biological axiom as our most succinct universal statement of ultimate organic agency.

Most of nature is mindless, but that does not mean that there are no reasons or purposes for organic structures and behaviours. This is how we explain functional and adaptive traits: not as a heuristic device but as a naturalistic account of the biological world.

Conscious reasons are simply reasons of a particular (emergent) kind. Humans exhibit purposive behaviour motivated by their intentional psychology. But purpose has a grounding concept too. Unconscious and mindless goals and purposes are all around us in nature. There were reasons (purposes, goals) in nature long before human minds evolved, even though humans as reason-representers are the only creatures that are aware of this (Dan Dennett). And organisms manifest purposes in a way that the inanimate world does not.

And yet, a plant ‘wanting’ water?

Perhaps a dog ‘wants’ its owner to come home from work when it looks out of the window at the time when the owner usually comes home? But does a tree ‘want’ light and water? Does a worm ‘want’ damp earth?

‘Wanting’ is most familiar to us as an element of our intentional psychology. But there is, nevertheless, a sense in which we understand that trees share the same agency as all other living organisms and therefore the same (in the emergent language of human intentional psychology) ‘wants’, ‘needs’ or ‘dependencies’ based ultimately on their propensity to survive, reproduce, and flourish. Certainly, the ‘wanting’ of a plant is extremely different from the ‘wanting’ of a human being. But then, the ‘wanting’ (dependency) of a plant on water is extremely different from the ‘wanting’ of a river to reach the sea. There is a behavioural orientation (motivation, agency) in mindless organisms that is like human minded agency: it is different from human agency but it is real, and it is different from activity in the inanimate world. It is the biological agency that grounds the behaviour of all organisms, both minded and mindless.

Principle – biological language conventionally regarded as inappropriate cognitive metaphor can also be regarded as the communication of the properties of universal biological agency as fostered by human cognitive bias, convenience, our intuitive recognition of non-cognitive (natural) agency, and an absence of non-human agential vocabulary

Agency & evolution

Today’s science views the living world through the lens of evolutionary biology. Clearly, in the course of evolution, agential matter adapted, differentiated, gathered complexity, and eventually and miraculously became self-aware, to manifest the emergent intentional attributes we now know as ‘meaning’, ‘knowledge’, ‘purpose’, ‘reason’, ‘value’, and so on. In other words, human agency evolved out of biological agency, and mind evolved out of the mindless agential organisms that had, in turn, evolved out of non-agential matter.

The evolutionary differentiation and radiation of intergrading living forms into a community of life, is the physical outcome of principles expressed in the biological axiom – a manifestation of biological agency in process.

The seeds of human intentional faculties were present in the universal preconditions for agential existence that arose at the dawn of life. However, just as humans were only one of many evolutionary outcomes, so too was their intentional experience.

The universal agency expressed in the biological axiom is manifest in as many different physical forms as there are species, humans being just one of these expressions. The biological axiom is like the soil out of which everything living has grown, including the animals that are dependent on plants for their existence.

A student of agency would investigate the agencies of microbes, plants, fungi and indeed all organisms, not just that of humans. The reason we pay so much attention to the human expression of agency is because of its exceptional properties of conscious awareness and deliberation, along with the agential powers that this brings. But from an evolutionary perspective this is simply a case of human self-interest and exceptionalism because the overriding importance we attribute to human conscious mental experience is just one outcome of the agential goals that ground all life.

Principle 12 – human (minded) agency evolved out of the (mindless) biological agency that is expressed in the biological axiom i.e. mind evolved out of the mindless agential organisms that had, in turn, evolved out of non-agential matter. We emphasize human agency because of its exceptional properties of conscious awareness, deliberation, and agential power. But, from an evolutionary perspective, this is a form of speciesism with human intentionality the agential evolutionary outcome for just one species.

Cognitive metaphor

What does this discussion mean for the biological language that is so widely regarded as cognitive metaphor?

When we use a locution like ‘The spider builds a web to catch flies’ we might assume (it is not explicit) this implies that spiders have human-like cognition: they have devised a cunning plan for catching flies. We might then assume, by an error of reasoning, that since spiders have no human-like cognition then there are no reasons for their actions (an intention fallacy?). Certainly, humans, as reason-representers, are the only organisms that are aware of spider reasons, but reasons exist in nature independently of humans, and spider webs catching flies is one of these.

Spider reasons are an expression of biological agency (its mindless behavioural orientation and goals), not human intention, and these goals are real. It is therefore misleading to say it is ‘as if’ spiders build webs to catch flies. The statement ‘spiders build webs to catch flies’ may be taken at face value as an example of a mindless goal (functional adaptation). We cannot say that because this goal is mindless it is not real: a rock could never have such a goal.

However, when we use a slightly different locution such as ‘The spider knows how to build its web’, surely this time we explicitly and mistakenly imply that spiders have human-like cognition, and we are confronting a clear case of cognitive metaphor?

But maybe when we refer to spider ‘knowing’ we are not trying to infer the emergent, subjective, and intentional human form of knowing, rather the grounding and objective fact that it is astounding how, without any learning, spiders build something so intricate and purposeful as a web: that in some miraculous way the ability to build webs has been passed from parent to offspring as a kind of mindless knowledge and knowing. The language is undoubtedly cognitive metaphor, but this does not make its referent unreal.

If this is indeed what is being communicated, then this is not cognitive metaphor or ‘as if’ language – it is simply implying that spider ‘knowing’ is like human knowing in some ways and therefore much more like simile – and the form of spider ‘knowing’ being described is a ‘real’ form of biological agency (yes, it is ‘as if’ it is human cognition; but no, it is not ‘as if’ it exists as a form of biological agency).

Though we can point to ‘non-cognitive characteristics encoded as adaptive traits in spider genes’ as the source of this kind of knowledge, it is the biological agency (grounding concept) that is of special interest. Subjective traits are also generated by genes.

On the analysis presented here, spider knowing is best treated, not as an ‘as if’ (unreal and mistaken) claim that spiders have human-like cognitive faculties, but as a real likeness in the way that both humans and spiders share biological agency.

Principle – we use cognitive human-talk for several reasons: because we intuitively notice the real grounding similarities that exist between human agency and the goal-directed agency of mindless organisms (as expressed in the biological axiom); to compensate for a lack of technical vocabulary; and because of the post-Darwinian need for biological concepts to assume meanings that have absorbed the latest biological research

Principle – science does not have the technical vocabulary to express the gradation of many of its concepts especially those whose primary understanding comes from the human experience e.g. consciousness. To overcome this, we can either imply an extension of the semantic breadth of existing language (e.g. infer that consciousness extends beyond humans) or we can restrict the use of these words to humans (denying any evolutionarily pertinent connection) and wait for scientific terminology to catch up

The metaphor fallacy

‘That plant wants water‘

The metaphor fallacy is a confusion arising out of the use of the language of human intentional psychology to describe mindless (non-cognitive) but real and agential (goal-directed) behavior and traits. Describing real biological agency using the language of human agency results in a cognitive metaphor because we cannot describe non-cognitive agential traits in cognitive terms. When interpreted literally, the use of cognitive terms to describe non-cognitive circumstances is a scientific mistake.

Confusingly, the intention of the words does not align with their literal meaning.

So why aren’t we more precise?

We use ‘cognitive’ words because there are no appropriate ‘non-cognitive’ words to do the job required. Cognitive words are the best available words.