Indian Ocean

Map of The Indian Ocean

The World Factbook – 2002

Courtesy United States Central Intelligence Agency

Introduction – Indian Ocean trade

The sea, often regarded as a featureless expanse of separation, has throughout history, served as a medium of connection. One remarkable example supported by both archaeological and genetic evidence is the first major settlement of Madagascar – not from East Africa across the Mozambique Channel – but from Indonesia 6500 km away.

International commerce, even in antiquity, generally entailed trade routes across both land and sea, the ancient Indian Ocean maritime trade routes linked to the Silk Road.

The scarce energy of human and animal muscle power used for transportation on the Silk Road meant that profits must be gained by trading in light and precious luxury goods like jewelry and spices. By harnessing wind-power, ever-larger ocean-going vessels and merchant navies, it became possible to trade in bulk – cotton, cloth, timber, pottery, animals, grain . . .

Among the articles transported by sea were sometimes live plants, especially those that could be easiloy reproduced and quickly re-established in a new environment such as the vegetatively propagated taro, banana, coconuts, sugarcane, and greater yam.

Human plant dispersal has proceeded at all spatial scales, from global to local. Goods were exchanged both in littoral trade using small craft like canoes and rafts along coastlines, but increasingly with ocean-going vessels whose shipbuilding and navigation technology was being constantly improved. Trade was therefore often of local significance only, while at other times it was a consequence of decisions made in the interests of regional or imperial authorities.

Historical background

Trade across the Indian Ocean can be traced back to antiquity, with evidence of maritime commerce dating as far back as the time of the Indus Valley Civilization around 2500 BCE. The Indian Ocean served as a vital corridor for the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures between the various regions bordering its shores, including the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Middle East.

One of the earliest recorded instances of Indian Ocean trade can be found in the writings of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who mentioned the seafaring activities of the Phoenicians and Egyptians in the Indian Ocean around the 5th century BCE. These early maritime traders played a significant role in facilitating the exchange of luxury goods such as spices, precious metals, gemstones, textiles, and aromatic resins between the East and the West.

The phenomenon of Indian Ocean trade reached its zenith during the medieval period, particularly between the 7th and 15th centuries, when a network of trade routes known as the “Indian Ocean Trade Network” emerged, connecting the major ports and trading cities of the region. This network was sustained by the monsoon winds, which facilitated the movement of ships laden with goods between the different regions along the Indian Ocean littoral.

One of the key drivers of Indian Ocean trade was the demand for spices, particularly pepper, cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg, which were highly prized in Europe, the Middle East, and China. These exotic spices, along with other commodities such as textiles, ivory, porcelain, and precious stones, were traded along established maritime routes that linked the bustling ports of the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa, and Southeast Asia.

The Indian Ocean trade network was also a conduit for the spread of cultural and religious ideas across the region. Islamic merchants from Arabia and Persia played a crucial role in the expansion of Islam in Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Indian subcontinent through their commercial activities and interactions with local communities. Similarly, Indian traders introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to Southeast Asia, where these religions took root and flourished.

The maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean were also instrumental in fostering diplomatic relations between the various kingdoms and empires that bordered the ocean. The Chola dynasty of southern India, for example, established a powerful naval empire that dominated the Indian Ocean trade network during the medieval period, extending its influence as far east as Southeast Asia and as far west as the Arabian Peninsula.

The decline of the Indian Ocean trade network can be attributed to a combination of factors, including the rise of European colonial powers in the region, the shift in global trade routes towards the Atlantic Ocean, and the advent of new technologies such as steamships and the Suez Canal. By the 19th century, the once-thriving maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean had largely been supplanted by the new patterns of trade emerging in the age of European imperialism.

The history of trade across the

Indian Ocean is a testament to the interconnectedness of the various regions bordering its shores and the pivotal role that maritime commerce played in shaping the economic, cultural, and political landscapes of the Indian Ocean world. Despite the changes brought about by colonialism and globalization, the legacy of this ancient trade network continues to resonate in the shared histories and traditions of the communities that once thrived along its bustling shores (AI Sider July 2024)..

Ancient trading blocs

The ancient world may be divided into six or seven major historical trading blocs:

Mediterranean – including Cairo

China – mostly in the Tang and Song dynasties traded silk, porcelain and tea mostly through the port of Gwangzhou (Macau)

Indian Ocean – Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Indian West Coast, and Sri Lanka: India divided into separate states but trading heavily through Calcutta in cotton, ivory, and spices

Bay of Benghal – Indian east coast, Bengal, Myanmar, western Malay coast

Middle East & Arabian Peninsula- Islamic empire especially the Umayyids and Abbasids. Trade including gold, frankincense and myrrh from Persia. Straits of Hormuz were a critical choke point connecting to the Mediterranean

East Africa – largely through Mombassa was traded ivory, gold, slaves, and exotic animals and their pelts. An Arabic diaspora settled here producing the syncretic African-Arabic Swahili language

Southeast Asia – Java Sea mostly during the Srivijaya (declined in 15th century) and Kmer cultures trading gold and spices with the religions of Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism being transmitted from India. The narrow Malacca straits were a choke point in trade between India, China and Japan. Between 600 and 1450 larger dhows with triangular lateen sails and eventually the use of astrolabe, compass, rear rudder

In the early 12th century the main port of Sri Lanka served as hub for the trade between the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal

WORLD SETTLEMENT

Modern Humans

Africa - 200,000 BP

India - c. 65,000 BP

SE Asia - c. 65,000 BP

China - c. 65,000 BP

Australia - 65,000 BP

Europe - 45,000 BP

Tasmania - 30,000 BP

Britain - 11,000 BP

Maldives - c. 500 BCE

Sth America - c. 15,000 BP

CE

Iceland - 874

New Zealand - 1250-1300

Porto Santo - 1418

Madeira - 1420

Azores - 1432

Cape Verde - 1442

Indian Ocean – Eastern Hemisphere of Earth

From Terra MODIS, Aqua MODIS, the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program, Space Shuttle Endeavour, and the Radarsat Antarctic Mapping Project. NASA images by Reto Stöckli, based on data from NASA and NOAA. Instrument: Terra – MODIS

2 October 2007, 08:47:55

Courtesy NASA & Wikimedia Commons – Accessed 10 September 2019

3300 to 1200 BCE

Cultural movements in the Indian Ocean region date back at least 8000 years [1] making this region a maritime focus of international trade and globalization alongside the great river valley civilizations of the Indus, Nile, Tigris and Euphrates. There is evidence for bitumen-coated reed craft in the western Indian Ocean around 3000 BCE and for plank-made vessels around 2300 BCE.[3] The Indian Ocean exchange of food plants may be divided into three zones with southern Asia (India, an early international trading hub for herbs and spices) located midway between the Afro-Arabian and southeast Asian trade routes. At its height there would have been trading connections between China, the Mediterranean and western Europe, and southern African kingdoms. Coastal regions, especially in India and the Arabian Peninsular may have served as agricultural experimental sites based on traded plants.[2]

The first ocean-going ships were built by Austronesians of SE Asia who, as early as 1500 BCE traded with southern India and Sri Lanka, the plants including coconuts, sandalwood, bananas, and sugarcane while the Indonesians traded spices, mostly cinnamon and cassia, across to East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

Ancient monsoon trade – 2500 BCE and 100 CE

Trade was shaped by the seasonal pattern of the monsoons with plants, in this period, absorbed into the Harappan civilization which stretched across today’s Pakistan and northern India. Monsoon winds carried trade west in winter towards Africa and east in summer towards India and Asia.

Plant exchange in the Indian Ocean during the period 2500 BCE and 100 CE is summarized below.

From East Africa to India:[4]

Sorghum– Sorghum bicolor – c. 2500-1700 BCE (in the Indus valley, Mature Harappan)

Pearl Millet – Pennisetum glaucum – c. 2000-1700 BCE (semi-arid parts of NW India, Late Harappan)

Hyacinth Bean – Lablab purpureus – c. 2000-1700 BCE (Late Harappan)

Cowpea – Vigna unguiculata – c. 1500 BCE (eastern Indus and upper Ganges, Late Harappan)

Finger Millet – Eleusine coracana – c. 1500-1000 BCE (eastern Indus and upper Ganges, Late Harappan)

From SE Asia and India to Africa: [5]

The history of banana domestication is complex.

Banana – Musa spp. – (Cameroun c. 800-300 BCE; Indus Valley c. 2000 BCE)

Coconut – Cocos nucifera – (?Peninsular India c. 1800-1500 BCE; E Africa c. 60 CE arrival ?500 BCE)

Taro – Colocasia esculenta – (multiple domestications in NE India, SE Asia, New Guinea; Africa ?1000-500 BCE)

Greater or Water Yam – Dioscorea alata – (domesticated in New Guinea then spread to SE Asia and arrival in Africa c. 1000-500 BCE)

Later possible food transfers from Africa to India to first millennium CE:[6]

The history of domesticated taro cultivars and SE Asian yams in both India and Africa is complex.

Jumbie Bead – Abrus precatorius – (3000-1500 BCE Harappan sites)

Horsegram – Dioscorea alata – (domesticated in New Guinea then spread to SE Asia and arrival in Africa c. 1000-500 BCE)

Greater or Water Yam – Macrotyloma uniflorum – (1800 BCE in Daimabad, Indian savanna 2000-1500 BCE)

Tamarind – Tamarinus indica – (native to Sudan c. 1600 BCE)

Bitter Melon, Balsam Apple – Momordica charantia, Momordica balsamina – (?400-200 BCE)

Okra – Hibiscus esculentus – (?400 CE)

Water Melon – Citrullus lanatus – (pre- 1700 BCE)

Water Melon – Citrullus lanatus – (pre- 1700 BCE)

‘By the time the Greeks and Romans entered the maritime world of the Indian Ocean, small and large ports in East Africa, Arabia, peninsular India and parts of Island Southeast Asia were not only linked by the exchange of precious commodities such as tortoise shell, rhinoceros horn, cinnamon, frankincense, myrrh, spices, sugar (from sugarcane) and palm oil, but also by the novel agricultural, pastoral and littoral landscapes composed of different combinations of ‘native’ and ‘introduced’ crops and animals brought together during previous millennia . . . the cuisines and cultivated landscapes of the hinterlands (having) differing combinations of a familiar repertoire of grain and vegetable crops representing the oceanic and continental botanical exchanges of the preceding 2000 or so years.’

SOUTHERN ASIA HISTORY

Palaeolithic -2,500,000–250,000 BC

Madrasian Culture

Soanian Culture

Neolithic - 10,800–3300 BC

Bhirrana Culture - 7570–6200 BC

Mehrgarh Culture - 7000–3300 BC

Edakkal Culture - 5000–3000 BC

Chalcolithic - 3500–1500 BC

Anarta tradition - c. 3950–1900 BC

Ahar-Banas Culture -3000–1500 BC

Pandu Culture - 1600–1500 BC

Malwa Culture - 1600–1300 BC

Jorwe Culture - 1400–700 BC

Bronze Age - 3300–1300 BC

Indus Valley Civn - 3300–1300 BC

– Early Harappan - 3300–2600 BC

– Mature Harappan - 2600–1900 BC

– Late Harappan - 1900–1300 BC

Vedic Civilisation - 2000–500 BC

– Ochre Pottery - 2000–1600 BC

– Swat culture - 1600–500 BC

Iron Age - 1500–200 BC

Vedic Civilisation - 1500–500 BC

– Janapadas - 1500–600 BC

– Black & Red Ware - 1300–1000 BC

– Painted Grey - 1200–600 BC

– Nthn Black Polished - 700–200 BC

Pradyota Dynasty - 799–684 BC

Haryanka Dynasty - 684–424 BC

3-Crow'd Kingds -c. 600 BC–AD 1600

Maha Janapadas - c. 600–300 BC

Achaemenid Empire - 550–330 BC

Ror Dynasty - 450 BC – AD 489

Shaishunaga Dynasty - 424–345 BC

Nanda Empire - 380–321 BC

Macedonian Empire - 330–323 BC

Maurya Empire - 321–184 BC

Seleucid India - 312–303 BC

Pandya Emp. - c. 300 BC – AD 1345

Chera Kingd. - c. 300 BC – AD 1102

Chola Emp. - c. 300 BC – AD 1279

Pallava Em. - c. 250 BC – AD 800

Maha-Megha-Vahana Emp. - c. 250 BC – c. AD 500

Parthian Empire - 247 BC – AD 224

Indian Ocean Trade

Maritime trade network of Austronesian peoples in the Indian Ocean

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Obsidian Soul – Accessed 6 Sept 2019

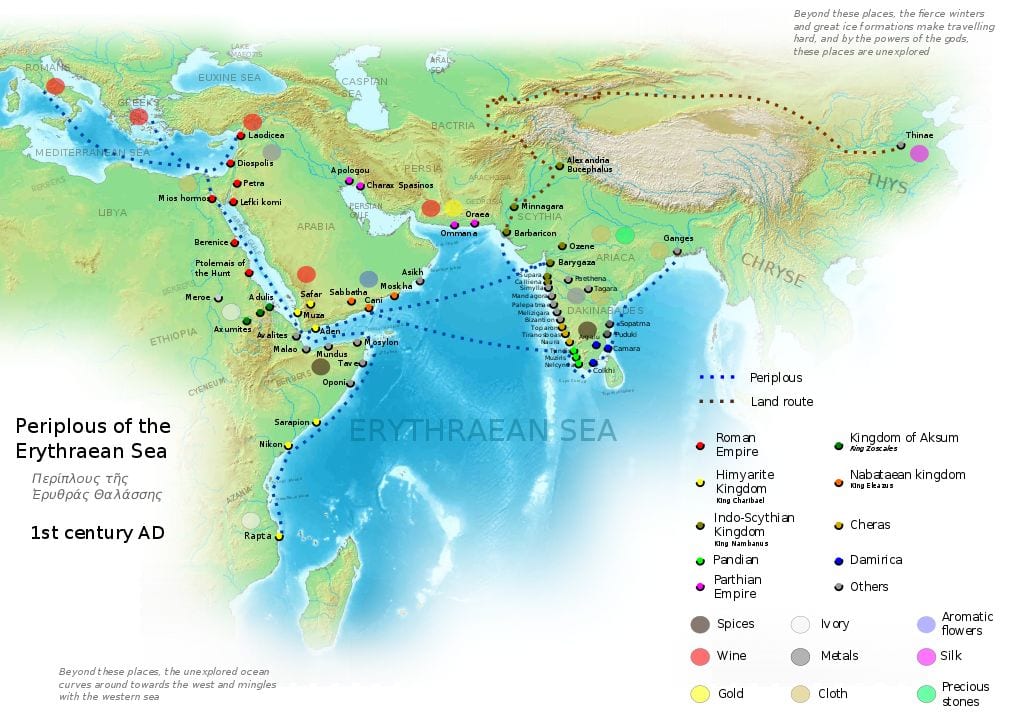

Roman trade with India according to the Periplus Maris Erythraei – 1st century CE

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – George Tsiagalakis / CC-BY-SA-4 license – Accessed 6 September 2019

1200 BCE to 1500 CE

We can assume that information and resource exchange occurred whenever it was advantageous and conducive to do so – including the dispersal of people, and both living and dead organisms. Historically, this has not occurred at a uniform rate.

From the 16th century European Age of Discovery onwards influences became more collective, regional and global. There was a rapid increase in the number and distance of the species distributed, the land surface that they covered, and therefore their social and environmental impact. This occurred under the influence of developed societies prompting geopolitical interpretations of the forces involved. ‘Ecological imperialism’ has emphasized the negative effects on environments and native peoples of European colonialism while the related ‘ecological nationalism’ has emphasized its role in nation-building and economic development. Regardless, the flow of biota in this period was mostly from the Old World to the New world, in effect creating environmental neo-Europes in the settler colonies.

Merchants from northern India settled in Myanmar, in the ports and towns located at the mouths of Irrawaddy, Citranga (Sittang) and Salavana (Salween) rivers. Ancient Pali literature reports merchants from Kamboja, Gandhara, Sovira, Sindhu saling from Bharukaccha (modern Bharoch) and Supparaka Pattana (modern Nalla-Sopara, near Mumbai) to trade with Southern India, Sri Lanka and nations of Southeast Asia. Huge trade ships sailed from there directly to south Myanmar around 1000 BCE.

Inland connections

Maritime trade routes were complemented by three inland trade routes, the Northern High Road (Uttarapath) between Bengali Tamralipti over the Gangetic Plains to Kabul and Samarkand in today’s E Afghanistan, the Great Southern Highway (Dakshinopath) between Pratishtam, Ujjain and Mathyura, and the Western Highway (Dwarawati-Kamboja) between west coast Dwaraka and todays Afghanistan and Uzbeckistan. These connected to the Silk Road to their north.

Uttarapatha was famed for its horses and the horse-dealers trading between the nations of Uttarapatha, like Kamboja, Gandhara and Kashmira and East Indian trading centres of the Gangetic Valley like Savatthi (Kosala), Benares (Kasi), Pataliputra (Magadha), Pragjyotisha (Assam) and Tamarlipitka in Bengal and possibly into Myanmar, south-west China and SE Asia. Around 127 BCE bamboos and textiles from SW China Chinese envoy Chiang Kien being told these had travelled from Yunnan to Burma then along the Northern High Road to Bactria and Afghanistan.

Hellenic trade

Ancient Greek navigators are well known for their voyages of exploration and adventure. Pytheas (fl. 4th century BCE) of Massalia (today’s Marseilles) who sailed to northwestern Europe in about 325 BCE. His account of the voyage is lost but reports by others claim that he circumnavigated Great Britain and Ireland.

According to the Periplus . . . discovery of the seasonal monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean is attributed to the Greek navigator and explorer Hippalus (fl. 1st century BCE), but this almost certainly ignores local knowledge that would have dated back much earlier.[2]

Greek traders are remembered for trade that connected the Mediterranean to the Red Sea later taken up by the Romans.

Roman trade

When Egypt was annexed by Rome in 30 BCE Roman trade with Africa and the Indian west coast gathered in volume based on two Red Sea ports. Myos Hormos was connected to the Nile Valley and Memphis by road and according to historian Strabo was visited by about 120 ships p.a. in Augustus’s reign in the 1st century CE. Indian ports visited included the Indus delta, Muziris and the Kathiawar Peninsula. Further south there was the trading centre of Berenice.

There is also good archeological evidence of Roman trade (1 CE to 200 CE) coming into Gandhara/Kamboja and Bactria region in Uttarapatha through the Gujarati peninsula. Roman gold coins imported to Gandhara were melted into bullion in this region.

Between 1st century BCE and the 6th century CE the island of Socotra (Dioskouridou of the Periplus . . .) which is situated 240 km off Somalia and now part of Yemen, served as a stopover for traders in frankincense, myrrh, pearls and cotton sailing mainly to and from the Indian west coast. In 2001 a cave expedition found about 250 inscriptions from this period in the Indian Brāhmī script but also in South Arabian, Ethiopic, Greek, Palmyrene and Bactrian languages. Socotra is still adjacent to major shipping routes.

Post-Roman

From the 6th century CE India’s east coast Tamralipti, Puri, Masulipatnam, Nayapattinam were hubs for Chinese silk.

From the 7th century Ethiopians travelled to Western India as merchants, sailors and indentured servants trading in the Red Sea and along the Arabian coast. Aden was the major hub for trade passing between India and Egypt, especially Cairo, also in later years a port called Aidhab.

Trade was vibrant through the Middle Ages in the ports, like Mangalore, along the southwest coast of India. Here merchants lived in fortified houses that also served as warehouses. In Mangalore the community, in around 1140, included Arabs, Gujaratis, Tamils, Jews who traded in the spices, mainly Black Pepper, that was grown on the hillsides of the inland Western Ghats. But there was also cardamon, coriander, ginger, turmeric, cloves, nutmeg and other plant-based lotions, medicines, and flavours.[7] At this time there was considerable freedom in the process of trade in Asia while in Europe ‘Guilds set the times and places of trade, controlled prices and quality of goods, and specified who could trade by mens of apprenticeships and member rolls’[8]

Modern era

In 1500 there were six major trade routes with the Ottoman Empire, which lasted from the 14th to the 20th centuries, at their hub:

1. The overland Silk Road connected China to the Ottoman Empire over the steppes of Central Asia

2. Using the Maritime Indian Ocean Route China traded paper, compass, silk, porcelain using the maritime near-coastal ending in the Red Sea in the Middle East and Ottoman Empire

3. Northern European River Trade, mostly amber, which linked the Black Sea and Baltic Sea through river systems

4. Western European Sea and River Trade linked in to Mediterranean system that also linked in to the Ottoman central hub

5. Mediterranean

6. Trans-Saharan trade across the Sahara Desert connecting the African Songhai Empire to the Ottoman empire

In the early 17th century Indian merchants settled in Zanzibar trading rice, ghee, spices, ivory, cloth and cotton.

Commentary

Our interest is primarily in the influence of plant trade on landscapes and social organization. Over longer time scales this must consider the influence of climate and sea level changes such as the sea level rise of from 5 to 7m that occurred from the mid-Holocene dry event around 6200 BCE to approximately current levels around 5000 BCE which, for example, resulted in the present-day arrangement of the islands in SE Asia and the oceanic separation of New Guinea from northern Australia.