Plant science people

People who influenced on our understanding of the human relationship to plants

Introduction – Plant Science People

A comprehensive compilation of the life and work of the people discussed here (and adding more) would be a great service to plant science. There are, of course, many biographic sources including: The encyclopaedia of ancient natural scientists: the Greek tradition and its many heirs edited by Paul Keyser and Georgia Irby-Massie (2008); for Britain the Oxford Dictionary of Biography,[11] and for Australia the Australian Dictionary of Biography, and Wikipedia and so on.

Most of the people outlined briefly in the article below are well known and well documented both in books on natural history and on web sites like Wikipedia (many abbreviated here). The list here is not intended as an authoritative reference but a way of establishing context and continuity in the unfolding of plant science – the countries where advances occurred, and the major personalities involved. Only a few of the many sources used to build up this biography have been listed. Though not strictly plant scientists, I have included well-known and frequently mentioned plant hunters, gardeners and administrators.

Assembling biographic information draws attention to the knowledge that is missing. All we can access is recorded history and much is clearly unrecorded. Many significant people will be omitted and those listed inevitably tend towards the dominant cultures because it tends to be they that do the recording.

I have included headings through the timeline to help focus on the major developments around that time. Similarly I have included ‘firsts’, written in red. These too are intended as landmarks in the unfolding of plant science history – they relate to the time of origin of new disciplines, inventions, modes of thinking, and ways of working. Sometimes they note the birth of new branches of study which, in turn, are frequently connected to the origin of new technologies.

Prehistory

Food, medicine, spiritual world

Beyond plant use as food, specialist plant knowledge related mostly to their medicinal use. Human health was deeply dependent on communication with the spiritual world and this realm was the preserve of a medicine man, shaman, or priest whose skills might involve sorcery, incantations, potions, spells as well as the medicinal properties of plants. The medicine-man possessed the knowledge and skills needed for the intercession between the physical and spiritual worlds, a role that in the formal religion of Catholicism would be taken up by the priest.

The human preoccupation with plants for agriculture and medicine would be only briefy interrupted by the plant science of Classical Greece which was lost for nearly two millennia before returning in the modern era. Even modern European monarchs employed personal physicians to manage their health as is clearly evident from the list of distinguished botanists in the timeline.

BCE

Medicine, plant lists, herbal remedies, plant hunting

3000-2000 – Egypt, Mesopotamia, Aegean ‘ . . . gardens emerge as distinctly meaningful spaces’ [8]

2667-2648 – Imhotep – First great physician and founder of Egyptian medicine, later worshipped as a god and compared to the later Greek god of medicine Asclepios

c. 2000 -> – Egyptian physicians – In Bronze Age civilizations former medicine-man became priests. With the advent of writing plant lists and medicinal remedies were recorded for posterity. Egypt was renowned in antiquity for its sophisticated medicine. Plant remedies are recorded in the Hearst Papyrus (c. 2000 BCE), Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE), Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE), and London Medical Papyrus (c. 1325 BCE), but the most famous is the Ebers Papyrus which dates from the reign of pharaoh Amenhotep I

c. 1534 – Amenhotep I , it is a 110-page scroll about 20 metres long, probably copied from earlier texts. It is one of the oldest preserved medical documents and is likely the world’s earliest surviving list of medicinal plants containing some 30 herbal remedies.

1508–1458 – Pharoah Hatshepsut – Egypt, Thebes – Plant geography and exploration

Identification, landscape design

1479-1425 – Pharoah Tuthmosis III – Egypt, Thebes – Plant geography and exploration. Bas-relief at his Temple of Karnak known as the ‘Botanic garden‘ depicts plant trophies from Syria, Palestine and elsewhere possibly serving as an identification guide

1114-1076 – King Tiglath-Pileser I – Mesopotamia, Assyria, Assur – Plant geography and exploration

r. 705-681 – King Sennacherib – Mesopotamia, Assyria, Assur – Cultivated plants. Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the most outstanding landscape garden of the ancient world now located at Nineveh

Descriptive botany

668-627 – King Ashurbanipal II –Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Babylon – List of c. 160 plants medicinal herbs, 100 identifiable – ‘the earliest truly botanical work at present known’‘[1] Tablets stored as a library in his palace record herbs grown in medicinal gardens and listed as a materia medica and refer back to the second half of the third millennium BCE

c. 610 – c. 546 – Anaximander – Miletus – Possibly drew the first map of the world (improved by Hecataeus). First biological theoretician: that living creatures, including humans, arose out of nature, from the moist element or a mixture of water and earth as it was heated and evaporated by the Sun. Man must have been born from a different species. He developed crude theories of evolution and adaptation.

560-480 – Susruta – India – c. 700 plants listed in the Susruta-Samhita list of herbal remedies; plant knowledge equal to that of Egypt

c. 500 – Mago – Carthage Author of a 28-book agricultural manual written in Punic as a record of the farming knowledge of the Phoenician Berber colony of Carthage in North Africa, the granary of the central Mediterranean at that time. Romans sacked Carthage in 146 BCE and the Carthaginian libraries given to the kings of Numidia, with the exception of Mago’s book which was brought to Rome. Only a few fragments of Greek and Latin translations survive but it was a work widely quoted by the later Roman writers on agriculture.

c. 500 – Shénnóng Běncǎo Jīng; (Wade–Giles) – – China – the oldest recorded Chinese Herbal

c. 494 – c. 434 – Empedocles – Akragas, Sicily – First to distinguish plants from animals but also considered the change from inorganic to organic matter. He compared seeds to eggs and discussed plant nutrition as well as the adaptation of organisms to their environments. He is best known for the theory that the world consists of four fundamental elements: Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.

c. 480 – Menestor – ?Sybaris, Italy – Pythagorean and first to study plants exclusively, physiology, deciduous and evergreen, climatic tolerances, taste, flammability – interpreted in terms of Pythagorean hot and coldmedical theory. Regarded by Theophrastus as his predecessor.

c. 460 – c. 370 – Hippocratic Corpus – Greece – Medicine – Hippocratic Corpus a collection of lists of medicinal plants housed in the library at Alexandria and attributed to Hippocrates of Cos and his followers and constituting a summary of Greek medicine of the fifth and early fourth centuries. Two influential schools of medicine existed in Ionia of the late fifth and early fourth centuries, one at Cos and the other at Cnidos. Hippocrates of Cos is regarded as the Father of Medicine since he established it as a distinct discipline around this time. Over 230 plants are named without descriptions: foods are grouped according under headings of seed, fruit, root, fruit, or leaves

4th century – Hippo – Unknown nativity – Contrary to the prevailing belief that cultivated plants were the gift of the gods, Hippo maintained that they were a consequence of human attention

c. 431- 354 – Xenophon – Athens – Wrote Oeconomicus (c. 360) on estate management at a time when several of the first treatises on agriculture (by Chares of Paros, Apollonius of Lemnos, now lost but mentioned by Aristotle) were popular

c. 375-c. 295 – Diocles of Carystus – Greece, Athens – Physician and contemporary of Theophrastus in Athens. Wrote on both food and drug plants, notably the first Greek medicinal treatise written in Attic rather than the traditional Ionic, the standard textbook on medicinal plants in his day but now mostly lost but probably the source of many plant descriptions and names used Theophrastus, Crateuas, Dioscorides, Pliny and therefore the Medieval herbals. He is said to have coined the word ‘anatomy’.[5]

Birth of plant science

c. 371–287 – Theophrastus – Greece – The first non-utilitarian studies of plants: their structure, physiology, morphological diagnosis, geography, ecology and sexuality in two formal tracts: Enquiry into Plants and History of Plants the first formalised treatises on plant science and, in effect, the world’s first theories of plant form and function, the first botanical text books on plant science as a subject of study that was independent of medicine. However, botany would be absorbed into medicine for nearly 2000 years before the rediscovery and printing of Theophrastus’s books in 1483 during the Renaissance of learning.

Roman agriculture, botanical illustration

234–149 Cato the Elder Roman senator, historian (the first to write history in Latin) and avid farmer who wrote De Agri Cultura (On Agriculture) (c. 160) at a time of expanding Roman agriculture that used slave labour. A Roman textbook that emphasised the profitability of vineyards.

fl. c. 150 BCE Nicander of Colophon was a Greek poet and physician from Claros in modern Turkey, active at the time of Attalus III of Pergamum, his family held a hereditary priesthood of Apollo. His notes on plants occur in Alexipharmaca which comprises 630 hexameters on poisons and their antidotes, probably derived from other sources. He was respected in antiquity for his pharmacology and a popular literary author imitated by Virgil and Ovid, admired by Cicero, and frequently quoted by Pliny

c. 120-60 – Crateuas – Most notable herbalist and Court physician to Mithridates VI of Pontus (eastern Black Sea region of Turkey). He made an alphabetical list of plants with their synonyms and medicinal uses, the Rhizotomikon, which is now lost but almost certainly incorporated the work of Diocles. A second work is an illustrated supplement of paintings that constitutes the first botanical illustrations as deliberate technically accurate plant depictions. This work was the main source of information for the herbal of Roman pharmacologist Sextius Niger on which Pliny and Dioscorides relied.

116–27 Varro, Marcus Terentius A Roman scholar and writer, probably an equestrian and consulted on Caesar’s agrarian scheme for the resettlement of Capua and Campania. His best known work is probably the Nine Books of Disciplines used by later encyclopedists such as Pliny the Elder: it uses the liberal arts as organizing principles, Varro identifying nine of theseL: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, musical theory, medicine, and architecture, the basis for the seven classical liberal arts chosen for medieval schools. His only remaining complete work is Rerum rusticarum libri tres (Three Books on Agriculture, better known as De Re Rustica) which anticipates microbiology and epidemiology.[6]

70-19 – Virgil (Publius Virgilius Maro) was a Roman Epicurean philosopher and orator under Augustus (63 BCE-14 AD). Virgil’s most famous poetry was the Bucolics (Eclogues), Aeneid and Georgics. He is mentioned here less for his originality or plantsmanship than for his wide influence and the 164 plant species that are mentioned in the four books of Latin hexameters that was the Georgics. Book one including cereals, book two the vine and fruit trees, and book four a short section on horticulture. He no doubt influenced the later work of Columella and Palladius.

c. 64-? – Nicolaus of Damascus – Damascus – Medicine – De Plantis (On Plants) exists as a Syriac version translated into Arabic c. 900 by Ishaq ibn Hunayn and once included in the Corpus Aristotelicum. In 13th century rendered into Hebrew and Latin. It was discovered in Istanbul in 1923 and also exists as a Syriac manuscript in Cambridge. In two parts now regarded as derived from Theophrastus with some of his own additions, the first deals with plant parts, structure, classification, products, propagation and fertilization. The second describes origins, material composition, and the effects of external conditions and climate on plants, effects of locality, parasitism, the production of fruits and leaves, colours and shapes, fruits and their flavours and including water plants and rock plants. Much later, in the 12th and 13th centuries this second-rate work was mistakenly ascribed to Aristotle. Allegedly a friend to emperors Augustus and Herod.

CE

c. 25 BCE – c. 50 CE Cornelius Aulus Celsius – A Roman encyclopaedist and author of De Medicina (On medicine), considered one of the most important medical treatises of late antiquity and the only surviving section of a much larger encyclopedia: it draws on knowledge from ancient Greek works, and is considered the most comprehensive surviving treatise on Alexandrian medicine. The work’s encyclopedic arrangement follows the three-part division of medicine established by Hippocrates and Asclepiades — diet, pharmacology, and surgery — and exhibits a sophisticated knowledge of medicine. This codex is stored in the Plutei Collection of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence

4 – c. 70 Lucius Columella – The greatest author on agriculture in the Roman empire but, while careful in reporting his experiences and observations, he paid little attention to botany. Probably born in modern Cádiz his twelve volume Res Rustica is a masterly summary of Roman agriculture and draws on many other authorities including Cato the Elder and Varro. He is also the likely author of a book on trees, De Arboribus. Roman scientific agriculture persisted in the western world through the Middle Ages, the work of Columella copied and degraded through the years by writers like Gargilias Martialis (3rd C), Palladius (5th C) and Cassianus Bassus (6th C).

23–79 – Pliny the Elder – Italy – His 37-volume Naturalis Historia was a compendium Classical knowledge that included plants in volumes 12 to 26, his lists mostly derived from Theophrastus. Though about double the number there are many synonyms and questions of identification, although he did support botany as an independent subject. Pliny and Dioscorides were contemporaries unaware of one-anothers’ work. The text of Theophrastus available to Pliny and Plutarch may have been fuller than the one we know.[7]

c. 40–90 – Pedanius Dioscorides – Considered the father of pharmacology he was born in Turkey becoming a Greek physician in the Roman army travelling widely through the Roman Empire. His grand 5-volume De Materia Medica (see here) compiled in about 60 CE summarized Greek pharmacology and replaced the Rhizotomikon of Crateuas. It described about 600 plants and its first Byzantine translation was in 512 CE, the most impressive being one illustrated in colour, the Codex Vindobonensis being produced in Constantinople for a Byzantine princess and now housed in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. Then, in the 10th century, during the times of ʻAbd al-Rahman III (891−961), caliph of Cordova, the work was translated into Arabic, followed in 1518 at the Escuela de Traductores de Toledo, Spain, (the School of Translators of Toledo) Antonio de Nebrija made the first translation of the work into Latin. Its strength was the host of local names , the Latin and Greek names with synonyms, but also the additional names used in Egypt, Syria, Persia, Africa, Iberian Peninsula and Etruscan names where appropriate. A later compiler added coloured illustrations, probably copies from Crateuas. As the standard reference for western pharmacology until the Renaissance, it was widely plagiarized by Medieval herbalists and supplemented with descriptions of plants from India and the Arab world. In spite of all this his descriptions lacked the diagnostic authority we see in Theophrastus. Pliny and Dioscorides were contemporaries unaware of one-anothers’ work. The work was translated by English botanist John Goodyer (for personal use) n the years 1652-1655 but this was not published until 1934. (see Beck for English translation).

129-200 – Galen – Greece, Pergamum – Medicine – travelled and studied at Smyrna (now Izmir), Corinth, Crete, Cilicia (now Çukurova), Cyprus, Athens, and the great medical school of the day at Alexandria, following the theory of humours that had been passed from Hippocrates. Arguably the greatest physician of the classical world who synthesised Greek medicine in a system that would persist to the Renaissance and beyond. His later years were spent in Rome where he served as physician to Marcus Aurelius and also treated the wounded gladiators. His major contributions were in the anatomy and phyiology of animals and man. He recorded the medicinal effects of about 450 plants, following Dioscorides, but he encouraged his students to collect and recognize plants for themselves

c. 250 – Gargilius Martialis – Roman – writer on horticulture, botany and medicine. Fragments of his work (? De Hortis) have survived as an appendix to the Medicina Plinii(an anonymous 4th century handbook of medical recipes based upon Pliny the Elder Naturalis Historiae xx–xxxii). It discusses the cultivation of trees and vegetables and their medicinal properties including apples, peaches, quinces, citrons, almonds, chestnuts, parsnips, and various other edibles but with the clear influence of Dioscorides.

c. 350 – Apuleis Platonicus (Apuleius Barbarus, Pseudo-Apuleius) – A pseudonym for an author who produced the Herbarium, a manuscript herbal that comprised 129 remedies as an inferior reduction of Dioscorides work. It was, however, the first work to connect Britain with the herbal knowledge of southern Europe, probably through copies made just after the Norman conquest.

c. 350 – Theodorus Priscianus – was a Roman physician at the court of Constantinople during the 4th century. He was a pupil of the physician Vindicianus, and the author of the Latin work Rerum Medicarum Libri Quatuor at the end of the century. An unimportant work listing about 200 medicinal plants – only notable because a few of these were not found in either Dioscorides or Pliny.

fl. c. 390 – Marcellus Empiricus (Marcellus Burdigalensis, Marcellus of Bordeaux) – a Gaul from Bordeaux who wrote in Latin at the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries, his only remaining work is the derivative De medicamentis taken in almost its entirety from Scribonius Largius as pharmacological preparations. A weird mixture of former work, folk remedies, and magic. Notable only for its addition of some Gaulish names.

date sc. 450 – Palladius – Roman writer known for his book on agriculture Opus Agriculturae or De Re Rustica written in Latin and consisting of 14 books that were the primary reference through the Western Middle Ages in spite of Columella’s superior contribution.

c. 560 – 636 – Isidore of Seville – Archbishop of Seville often called ‘The last scholar of the ancient world’ wrote the encyclopaedic De natura rerum (On the Nature of Things) from 612 to 616. It is a poor rehash of Dioscorides, Pliny, Columella and others.

659 – Chinese physicians – China Medicine, a national pharmacopoeia produced by imperial decree

c. 980-1037 – Ibn Sina (often Christianised to Avicenna) – Persia – Medicine – Persian polymath of the Islamic Golden Age that lasted from the 8th to the 13th centuries. His 5-volume medical encyclopaedia, the Canon of Medicine became a reference book for four centuries in both East and West. It included plants of the Arab world in addition to those of Dioscorides and the Hebrew tradition

1057 – Emperor Jen Tsung – appoints two naturalists, a physician and a scientist-statesman to revise the national pharmacopeia by asking district governors and magistrates to produce drawings of regional drug plants resulting in an illustrated pharmacopeia of about 1000 plants and illustrations of which about 100 were new

fl. c. 1077 – Constantinus Africanus – Carthage – A Saracen (Franco-Italian designation for Muslims from North Africa) who had travelled in India and Persia lived in the 11th century. The first part of his life was spent in North Africa and the rest in Italy at Salerno and the abbey of Monte Cassino translating into Latin the texts Aphorisma and Prognostica of Hippocrates, Tegni and Megategni of Galen, Kitāb-al-malikī (i.e. Liber Regius, or Pantegni) of Alī ibn’Abbās (Haliy Abbas), the Viaticum of al-Jazzār (Algizar), the Liber divisionum and the Liber experimentorum of Rhazes (Razī), the Liber dietorum, Liber urinarium and the Liber febrium of Isaac Israel the Old (Isaac Iudaeus). These translations were used as textbooks from the Middle Ages to the seventeenth century.

c. 1080 – c. 1152 – Adelard of Bath – worked in Laon, northern France where he combined the traditional learning of French schools, the Greek culture of Southern Italy, and the Arabic science of the East. His Quaestiones Naturales (1130-1140) (Questions in natural science) hints at a botanical revival by rehashing questions in theoretical botany asked by Hippocrates, but there is no new botany. He translated many (non-botanical) Arabic and Greek manuscripts into Latin and is best known for his work in mathematics and philosophy. It is he who possibly introduced Arabic numerals to the West.

1098– 1179 – Hildegard of Bingen – a German Benedictine abbess of Rupertsberg and Eibingen regarded as the founder of scientific natural history in Germany. Her Physica (1150-1158) contains nine books that describe the scientific and medicinal properties of various plants, the Diversarum Naturarum Creaturanum Libri XI assembled between 1150 and 1160 described the properties of 240 plants but without new knowledge or botanical detail

c. 1150-1225 – Serapion the Younger (Serapion the Elder, Yahya ibn Sarafyun, was an earlier medical writer) authored The Book of Simple Medicaments (De Medicamentis Simplicibus) of the 12th or 13th century, probably written in Arabic, though no Arabic copy survives. The late 13th century Latin version was popular and likely derived from a surviving Arabic text Kitab al-adwiya al-mufrada attributed to Ibn Wafid (d. 1074 or 1067). A Latin-to-Italian translation (1390-1404) with colour illustrations remains as the Carrara Herbal. Latin printed editions were made in 1473 (Milan), 1479 (Venice), 1525 (Lyon) and 1531 (Strasburg), the 1531 edition supervised by the botanist Otto Brunfels and elements also appear in a widely circulated Latin herbal by Matthaeus Silvaticus dated 1317 and which probably influenced the work of Peter Schöffer (first published 1484), Leonhart Fuchs (1542), Rembert Dodoens (1554), and others.

1193-1280 – Albert of Bollstadt, Albert the Great (Albertus Magnus) –Scholastic philosopher and Bishop of Ratisbon, he was educated principally at the University of Padua then taught at Cologne, Regensburg, Freiburg, Strasbourg, Hildesheim, and Paris – Medicine – A Dominican monk famous for the 7-volume De Vegetabilibus (1250-1260). He was the first to recognise the distinction between monocotyledons and dicotyledons and made careful observations of general wood anatomy, noting the dsitinctive anatomy of wood in the date palm. Book 6 includes the medical and economic uses of about 270 plants while Book 7 is the best account of agriculture since Columella. St Thomas Aquinas was one of his pupils

1197-1248 – Ibn al-Baytar – Spain, Damascus – Medicine – a pharmacist-physician from Andalusian Malaga who summed up Arab pharmacology of the day in Kitab Al-jami li-mufradat al-adwiya wa al-aghdhiya (The book of medicinal and nutritional terms) an alphabetical encyclopedia of about 1200 plants, 200 being new, in a work unknown and untranslated in Europe. He collected and studied widely from northern coast of Africa as far as Anatolia to Arabia, Syria, and Palestine, and quotes many earlier scientists, including Dioscorides, Galen, and Avicenna.

c. 1219-c. 1292 – Roger Bacon – Oxford – Medicine – an empiricist Franciscan friar. He taught at the University of Paris and andhis botanical work was influenced by Aristotle and the De Plantis of Nicolaus. Though emphasising experiment and observation much of his work on plants is highly speculative

c. 1280 – c. 1342 – Matthaeus Silvaticus- Italy, Salerno – Physician-botanist – major work a 650-page encyclopedia of medicinal plants (1317) Pandectarum Medicinae or Pandectae Medicinae in alphabetical order derived from other works but popular, running to at least eleven editions, and helpful in assessing the state of pharmacology and medicine in Europe in the late medieval era.. The medical school in Salerno translated Arabic texts to Latin: 233 of 487 plant names used by Matthaeus were Latinizations of Arab names

Terminology

fl. c. 1410 – Benedetto Rinio – Italian herbalist who wrote the herbal encyclopedia Liber de simplicibus published in Venice in 1419 with 440 exquisite illustrations by Venetian artist Andrea Amadio. The book described 450 domestic and 111 exotic kinds of herb with names in Latin, Greek, German, Arabic, several dialects of Italian, and Slavonic

1430–1503 – Johannes de Cuba (Johann Wonnecke von Kaub) was a German botanist-apothecary from Frankfurt, author of an early printed book on natural history, which was published in Mainz by Peter Schöffer in 1485 titled Gart der Gesundheit one of the group of Mainz incunabulae and also one of the first printed herbals in German reprinted until the 18th century who preceded the trio of Bock, Brunfels and Fuchs. A work that has many errors is compensated by the excellent woodcuts attributed to Erhard Reuwich.

1474-1537 Jean Ruel (Ioannes Ruellius) – Paris – Medicine – physician to Francis I and Professor at the University of Paris. He devised a technical botanical vocabulary that predated (and was superior to) that of the later Fuchs, all published in the 3-volume De Natura Stirpium (1536) containing descriptions of about 600 plants taken from the works of Theophrastus and Pliny and with French common names. Probably the first modern era attempt to popularise botany.

1484-1552+ Juan Badiano – South America – Medicine. List of 250 Aztec medicinal plants compiled by Martin de la Cruz transl. from Nahuatl into Latin as Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis (c. 1552)

1488-1534 Otto Brunfels – Germany – Herbal. In 1532 Brunfels became a City physician in Bern. In his botanical work his descriptions followed his own observations rather than copying the old authorities, the German plants being described under the German vernacular names. The botanical works Herbarum Vivae Eicones (portraits of Living Plants) (1530 and 1536, in three parts) and Contrafayt Kräuterbuch (1532–1537, in two parts) include beautiful woodcuts drawn by Hans Weiditz from living (rather than stylized) plants, making these books among the first modern era illustrated herbals to establish botanical verisimilitude and resist the practice of copying from existing accounts while at the same time being the first attempt at a compendium of plants in the known world: it distinguishes between plants with and without flowers.

fl. 1533 – Francesco Bonafede – appointed in 1533 to what constituted the world’s first chair of botany as Lector simplicium (Reader in simples) within the medical faculty of the University of Padua. The appointment was made by the senate of the Republic of Venice which dominated the spice trade at this time. Bonafede’s request for the construction of a herbarium and Hortus simplicium (medicinal garden) came to fruition in 1545

1490-1556 Luca Ghini – Bologna, Pisa – Physician-botanist – studied at the University of Bologna before becoming Lector Simplicium in 1534 then Professor Simplicium in 1538; invited by Cosimo 1 de Medici in 1544 to take the chair of botany at Pisa, along with being in charge of what is generally taken to be the first modern era botanic garden. He is also regarded as the originator of the herbarium, a collection of dried and labelled plant collections (hortus siccus or ‘dried garden’) prepared using a plant press, the specimens shelved systematically in a building called a herbarium. The exchange of dried specimens between botanists became commonplace at this time. This established the link between descriptive botany, botanic gardens and herbaria. Ghini, more than any other person, was responsible for the re-establishment of botany in the modern era

1493-1588 Nicolás Monardes – Spain, Seville – Medicine – a physician Historia Medicinal. . . later transl. as Joyful news out of the new found world. An Aztec Herbal comprising about 250 medicinal plants was translated from from Nahuatl to Latin as Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis in about 1552 by Martin de la Cruz and Juan Badinao and this work inspired Monardes’s interest in the medicinal properties of tobacco for which he is best known

1495-1537 Hans Weiditz – Germany – Botanical illustration – Renaissance artist of Strasbourg and Augsburg whose botanically sensitive woodcuts illustrating Herbarum Vivae Icones of Otto Brunfels revolutionized botanical illustration

1498–1554 Jerome Bock (Hieronymus Tragus) – Germany, Tubingen – Herbal, Kreutterbuch. Bock included natural distributions in his studies and ordered his plants using morphological characteristics

c. 1501-1568 Garcia de Orta – Portugal – specialized in tropical medicine working in India and especially Goa, his herbal Coloquies dos Simples e Drogas da India (1563) (Medicinal and economic plants of India). He is commemorated by the Jardim Garcia de Orta in Lisbon

1501-1566 Leonhart Fuchs (Fuchsius) – Germany – physician and botanist who studied at Munich and held the Chair of Medicine at Ingelstadt in 1536, moving to Tubingen where he founded its medicinal garden in 1535. His herbal, De Historia Stirpium Commentarii (1542) has 500 woodcut botanical illustrations excellent in likeness & accuracy. Among the plants described were some from the New World. Brunfels and Fuchs produced decriptions and illustrations of a core set of species making them identifiable regardless of the name used. Perhaps the most notable Renaissance herbal

1501–1577 Pietro Mattioli (Matthiolus) – Italian physician and naturalist born in Siena, who trained in Padua in 1523, and subsequently practiced in Siena, Rome, Trento and Gorizia. Personal physician to Ferdinand II and Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna. His major research was Commentarii in VI Dioscoridis Libris examining the identification of plants described by Dioscorides, Woodcut illustrations in his work were of a high quality and sufficient for identification, one being the first documented example of the tomato cultivated in Europe. The first edition contained about 500 illustrations a later edition 2000. Mattioli described several plants that had no known medicinal properties, thus reinforcing a botanical rather than medicinal tradition

1510–1568 William Turner – England, Italy – Medicine – known as England’s first botanist (Morton 1981, p. 150) he was a religious cleric who studied at Cambridge University and published a list of English plants Libellus De Re Herbaria (1538) later travelling to Italy to study at Ferrara and attend Ghini’s lectures in Bologna from 1540-1542. He was a friend of Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner. In 1548 he listed 37 new-found herbs among which was the tomato. He is best known for his 3-volume Herbal (1551, 1562,1568) (illustrated with woodcuts from Fuchs’s Herbal) and written in the vernacular and thus opening up plant knowledge to the general public

1541-1613 Jean Bauhin –France – Medicine – Jean studied in Basel then with Fuchs in Tubingen and also collected with Gessner who described him as ‘eruditissimus ar ornatissimus juvenis’. He then studied in Montpelier with Rondelet, eventually appointed physician to the Duke of Wurtemberg who owned a large garden at Montbeliard. The brothers Jean and Gaspard Bauhin began the process of world plant inventory, the European total at the end of the 15th century as represented within the range of herbals totalled about 1000 plants, the recorded plants bequeathed to the Middle Ages by antiquity. In the three folio volumes of Historia Universalis Plantarum (not published until 1650-51) Jean listed over 5000 plants with 3577 woodcut illustrations (mostly those of Fuchs) while his younger brother would later list over 6000 in the earlier-published Pinax (1623)

1514-1587 Francisco Hernandez – Spain, Seville and Toledo – Medicine – Court physician to King Phillip II of Spain. He studied medicine at the University of Alacala and in 1570 was sent to study polants of the New World for 7 years in Mexico where, eventually describing over 3000 Mexican plants, 1200 in detail in Index Medicamentorum (1607) and Quatro Libros de la Naturaleza y Virtudes de las Plantes y Animales Mexico (1615). Many of these were grown in the botanical garden at Huaxtepec[3]

Taxonomy & morphology

1515–1544 Valerius Cordus – Germany – Medicine, Taxonomy – worked in Marburg, Leipzig, and Wittenberg. He is noted for the his method of formal plant descriptions setting out the plant characters in an ordered sequence that is still loosely followed today. His works included a pharmacopoia Dispensatorium and Historia Stirpium at Sylva (1561)

1516–1565 Conrad Gessner – Switzerland, Zurich – a physician and polymath studied in Zurich, Strasbourg, Bourges, Basel, Lausanne and Montpellier, his Historia Animalium (1551-1558) taken as the starting point for modern zoology and the greatest work on the subject since Aristotle’s work of the same name. He made detailed illustrations of plants detailing for each the flowers, fruit and seed but his works remained unknown and unpublished until well after his death. His Herbal, Historia Plantarum produced between 1555 and 1565 was not published until 1750. His De Hortis Germaniae Liber (1561) lists over 1000 different plants that he observed growing in German gardens

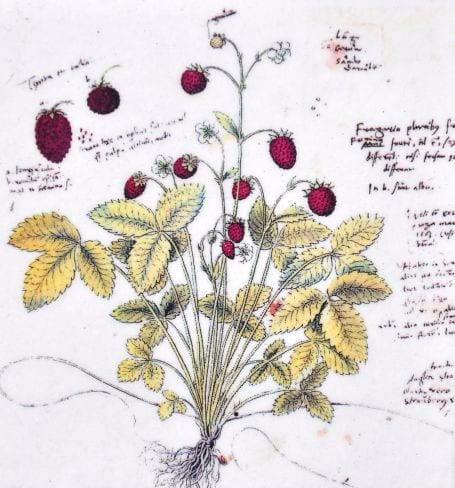

Illustration of the Strawberry, Fragaria vesca by Conrad Gessner

Botanical Garden Museum, University of Zürich : Fragaria vesca ‘Conradi Gesneri Historia plantarum’

Probably painted c. 1555-1565 but not published until 1750

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons, Roland zh Acc. 18 Aug 2016

1517–1585 Rembert Dodoens (Rembertus Dodonaeus) – Leuven, Vienna, Leiden – Medicine – Flemish (Flanders) physician botanist and court physician to the Austrian emperor Rudolph II in Vienna before becoming Professor of Medicine at the University of Leiden in 1582. His Cruydeboeck (1554) contained 715 images like those of Fuchs proving extremely popular with a number of original descriptions: widely translated across Europe it was used as a medical reference for about 200 years

1519–1603 Andrea Cesalpino – Pisa – Botany – De Plantis (1583) classifies about 1500 species: the first modern botany textbook and Caesalpino sometimes known as the first plant taxonomist

c. 1525 – c. 1594 Cristóvão da Costa or Cristóbal Acosta (Christophorus Acosta Africanus) – Portuguese doctor and natural historian who pioneered (with apothecary Tomé Pires and physician Garcia de Orta) the study of plants from India and Asia and their medicinal use publishing Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de la Indias Orientales in 1578

1526-1609 Charles l’Ecluse (Carolus Clusius) – Vienna, Leiden – Herbals, Botany – Trained with Rondelet at the Medical School Montpellier publishing a translation of Dodoens work. In 1573 he was appointed to the court of the Holy Roman Empire and in Austria from 1573-1587 he studied alpine plants of the Tyrol and Styria. He published Rariorum alioquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia . . . a Flora of Spain, in 1576. Rariorum Plantorum Historia . . . was a step towards a Flora of Europe, while Exoticorum Libri Decem . . . (1605) combined the listings of Monardes and de Orta, attempting to list all known tropical plants. An avid botanical correspondent.[9] Director of Hortus Academicus Leiden from 1593 to 1609 producing regular catalogues of the plant stock during the 1600s. His interest in ornamental plants especially those from foreign lands single out Leiden as a pioneering Hortus botanicus, not just a Hortus simplicius. A specialist in bulbs esp. tulips

1538-1616 Matthias de l’Obel (Matthaeus Lobelius) – Flemish – Physician-botanist – Montpellier, Holland, London – Herbal – Physician to William Prince of Orange and James I. His Herbal Icones Stirpium

c. 1545-1612 John Gerard –John Gerard English gardener-botanist who for 20 year managed a large tenement herbal garden owned by Lord Burghley in Holborn, London. Then from 1604 to 1586 curated a physic garden for the College of Physicians. Author of a 1,484-page Herball (1597), lavishly illustrated with woodcuts from Continental sources, and the most popular botany book in English in the 17th century but derived largely from Rembert Dodoens’s herbal (1554) which was available in Dutch, Latin, French and other English translations. He travelled abroad, probably as a merchant ship’s surgeon in the North Sea (Scandinavia) and Baltic (Russia). He received seeds and plants from around the world, especially those from the Americas and including seed from Jean Robin, the French king’s botanist, and Clusius the director of the Leiden Botanic Garden, the Hampton Court garden, and the gardens of various noblemen, offering advice. Though one of the founders of English botany he was more interested in gardens than theoretical botany. Linnaeus named Gerardia in his honour.

1547-1627 Jacopo Ligozzi – Italy – Born in Verona but becoming a painter in the Hapsburg court in Vienna before returning to Italy and the Medici family in Florecereplacing Vasari as director of the artists guild. His work included plants from the botanic garden in Bologna constructed by the naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi

1560–1624 Gaspard Bauhin – France – Medicine – Studied in Basel, Tubingen and Montpellier – also studying at Padua and Paris. At Basel he was appointed City Physician, Professor of Medicine and Rector of the Univesity. His Pinax (register) Theatri Botanici (1623) is a register of about 6000 known species with synonyms and references to other author’s works and illustrations that served as a plant register for about 100 years; it generally distinguishes genera and species, using a genus name and specific epithet as a binomial system devised over 100 years before Linnaeus

1561-1629 Basilius Besler – Germany, Nuremberg – Botanical artist employed by Bishop of Eichstatt in Bavaria to catalogue and illustrate the plants in the his botanical garden. Over a period of 16 years he produced Hortus Eystettensis (1613) with 1084 illustrations of culinary, medicinal and ornamental plants at near life size

1567–1650 John Parkinson – Britain – A London apothecary, herbalist, and gardener who became royal botanist to Charles I. He collected many plamts from the east Mediterranean and America but most famous for his Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629) and its description of flower, orchard, and kitchen gardens. Hi Theatrum Botanicum (1640) described about 3800 plants many of them novelties

1570-c. 1609 John Tradescant the Elder – Britain – Gardener, Plant Collector – Of yeoman stock he was a pre-eminent London gardener, introducing numerous exotic plants including the tulip. His own garden was in South Lambeth near Lambeth Palace. Friend of Frenchmen Jean Robin (Royal Herbalist to Henry IV and Louis XIII) and Rene Morin a great French nurserymen of his day and collector of natural history memorabilia. The Tradescants imported many plants from Virginia the ‘Younger’ visiting in 1637, 1642 and 1654, they had a virtual monopoly of plant introductions into England from North America (more than 90 new introductions)

1587–1657 Joachim Jung (Jungius) – Germany, Hamburg – Medicine, morphology. Worked in Rostock, the University of Padua, Lübeck, Helmstedt, and Hamburg. A wide-ranging intellect equal to the great men of his day eventually specializing in chemistry and botany. Published after his death were Isogoge Phytoscopia (a guide to examining plants) and De Plantis Doxoscopiae Physicae Minores (brief investigation of plants) which established a well-argued technical vocabulary for plant morphology improving on that of Fuchs and setting the stage for modern terminology.

1592–1664 – John Goodyer was described by botanist William Coles in 1657 as ‘the ablest Herbarist now living in England’ in 1657. As an apothecary Goodyer collected botanical works, translated works of Dioscorides and Theophrastus into English, studied plant nomenclature and botanized in his local countryside and beyond. His library was bequeathed to Magdalen College, Oxford. A visit to John Parkinson in London in 1616 appears to have sparked his field work which was mostly published by Thomas Johnson, collectively constituting an early attempt at guide to the English flora. In 1633 they published a revision of John Gerard’s Herball . . . (1597). He added many plants to the British flora and is believed to have specialized in elms, one now commemorating him through the name Goodyer’s elm coined by Kew botanist Ronald Melville as a form of the Cornish elm. He probably introduced the Jerusalem artichoke to English cuisine.

1596 – Li Shih-Chen outstanding Chinese scientist publishes Pen Tshao Kang Muover 1000 plants in a Great Pharmacopoeia but no recognition of botanical affinity

1605-1682 – Thomas Browne – was a polymath who graduated from Oxford in January 1627 then studied medicine at Padua and Montpellier universities before finishing his study at Leiden with a medical degree in 1633. He was a friend of John Evelyn and in his work The Gardenof Cyrus (1658) he traces the history of horticulture from the garden of Eden to the Persian gardens in the reign of Cyrus, paying special attention to the quincunx.

1620-1706 – John Evelyn – was an English writer, gardener, diarist (at the same time as Samuel Pepys) and social commentator during events such as the English Civil War, execution of Charles I, Oliver Cromwell’, the Great Plague and Great fire of London in 1666. His best known horticultural work was Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees (1664, repr. 1670,1679,1706) a plea for reafforestation to provide timber for England’s gathering navy.

1620 – 1683 Robert Morison – a Scotsman from Aberdeen who studied in Paris under Vespasien Robin, botanist to the king of France. For 10 years Morison was director of the Royal Gardens at Blois, Central France as physician in the household of Gaston d’Orleans (1608-1660), the uncle of the King. In 1621, Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby donated £250 to Oxford University for a physic garden and further money for a chair in botany. A royalist, Morison returned to England in 1669 with the restoration of Charles II (1630-1685), laying out St James Park and being awarded the title Royal physician and Botanist. He was then appointed the first professor of botany at Oxford, a post that he held from 1669 until 1683. His Praeludia Botanica emphasized the importance of fruits in classification and marked a turn away from medicine to descriptive botany. Specializing in the Umbelliferae he was the first to write a monograph on this group in his Plantarum Umbelliferarum Distributio Nova (1672) which included a statement of his method. His work was a precursor to that of the great John Ray. His three volume Plantarum historiae Universalis Oxoniensis (1680) was only partially completed. Part I on Trees and Shrubs was never published. Part II included just five of 15 projected sections on herbs when he was killed in a street accident, the work completed in 1699 by Jacob Bobart the Younger (1641-1719), Keeper of the Oxford Physic garden. German botanist Schelhammer (1649-1716) claimed to have seen the whole work at Morison’s house. Morison strived to develop a classification based on natural relationships and though he owed much to Caesalpino his work was in turn a strong influence Tournefort.[10]

1623–1705 John Ray – England – Botany, Floras, taxonomy (monocots, dicots), Historia Plantarum (world flora). Ray’s classification was based on relationship of form, his system species was based on gross morphology outlined in his Methodus Plantarum (1703) where the second edition records about 18,000 species and he distinguishes monocots and dicots, fruit types, and more, subdividing using leaf and flower types. Though technically advanced the use of phrase names rather than binomials made it cumbersome to use. His Catalogus Plantarum circa Cantabrigiam Nascentium (1660) was the first British county flora and Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum (1690) is effectively Britain’s first Flora. The increasing number of new species recorded by Ray was partly the result of his narrow species concept but also a consequence of the plant exploration beyond Europe.

1626–1662 – William Coles is best known for the ‘doctrine of signatures’ whereby a property or form of the plant indicate its possible medicinal use. In 1642 he entered New College, Oxford to be made postmaster of Merton College, Oxford. London’s Putney was ‘where he became the most famous simpler or herbalist of his time’ (Athenæ Oxon.). His major works were The Art of Simpling, or an Introduction to the Knowledge and Gathering of Plants (1656) and Perspicillum Microcosmologicum . . . and Adam in Eden, or Nature’s Paradise. The History of Plants, Herbs, Flowers, with their several, . . names, whether Greek, Latin, or English, and . . . vertues (1657).

1630-1715 – Duchess of Beaufort a friend of John Ray and Hans Sloane, Mary Somerset accumulated and recorded both living and dried plants from her collections in London and Badminton (accumulated from South Africa, West Indies, Sri Lanka, Virginia, India, Japan and China) , the latter with fine stove houses, orchard and orangerie. Many plants were acquired from George London of the Brompton Park Nursery and gardener to William III at Hampton Court. She bequeathed a 12-volume herbarium of pressed plants to the Natural History Museum.

1632-1713 – Henry Compton, the Bishop of London was responsible for the Church of England overseas, notably the British colonies in America, Caribbean, India and Africa. Suspended by James II for his Protestantism, Compton indulged his botanical and horticultural interests by building up his collection of plants (many from Rev. John Banister in Virginia, America) at his Fulham Palace where, by 1675, the numbers challenged those of other major collections, and impressed other members of the Temple coffee House Club including George London of Brompton Park Nursery who he employed as his gardener. Hortus Kewensis records over 40 new introductions supplied by Compton. Other overseas connections included Rev. John Clayton of Jamestown, William Berkeley and Mark Catesby, Governor of Virginia and English naturalist respectively. Also plants came in from Scottish surgeon-botanist James Cunningham, James Petiver And some of the 800 or so plants brought back from Jamaica by Hans Sloane that were also shared with the Duchess of Beaufort, Mary Somerset. Upon his death, plants from the garden were distributed to the Chelsea Physic Garden, University of Oxford Garden and elsewhere[12]

c. 1640–1714 George London an eminent English nurseryman, garden designer and founding partner to the Brompton Park Nursery in 1681. With his former apprentice Henry Wise (1653–1738) he designed the parterre gardens at Hampton Court for William III, was gardener to Henry Compton (bishop) at Fulham Palace, and worked on the gardens at Chelsea Hospital, Longleat, Chatsworth, Melbourne Hall, Wimpole Hall and Castle Howard. Those at Hanbury Hall near Bromsgrove have now been recreated following his design.

d.1644 – Thomas Johnson was an English botanist sometimes called the ‘Father of British field botany’ and member of London’s Society of Apothecaries by 1626. In 1629 he had a business at Snow Hill, London, with a physic-garden where Britain’s first bunch of bananas was placed on display. His most significant work, with John Goodyer, was his 1633 (repr. 1636) revision of Gerard’s Herball (to which were added over 800 new species, 700 figures, and many corrections resulting in 2,850 descriptions, referred to by John Ray as ‘Gerard emaculatus’). This was in competition with John Parkinson’s Theatre of Plants. In 1634 Johnson published Mercurius Botanicus; sive Plantarum gratia suscepti itineris, anno 1634, description, a 78-page record of plants he observed on a trip around Oxford, Bath, Bristol, Southampton, and the Isle of Wight, and including English and Latin names. In 1641 came Mercurii Bot. pars altera which described a visit to Wales and Snowdon on another of his ‘simpling trips’ searching out medicinal plants. 1643 he published a translation of the surgical works of Ambroise Paré from the French, which was reprinted in 1678. With his collecting companion John Goodyer he planned a flora that would free medicine from ‘women who dealt in roots’ but this goal was pre-empted by his death on the royalist side in the English civil war.

Microscope & anatomy

[4]

1628–1694 Marcello Malpighi – Italy – Anatomy, Histology, Physiology, Embryology – Educated at the University of Bologna, briefly holding a chair at Pisa and Messina, developing a correspondence with the Royal Society in London which published his 2-volume treatise on plant anatomy Anatome Plantarum (1675, 1679) which included work on plant embryology and developmental anatomy. The work of Grew and Malpighi, with minor addition from Leeuwenhoek, would stand for 150 years

1636-1691 Hendrik van Reede – Netherlands – Worked for the Dutch East India Company in Cochin and Malabar in southwest India, then the Cape, Sri Lanka and Bengal. Netherland led tropical botany partly because Reede organised a large team of botanists and illustrator to describe the plants of Malabar (medicinal and economic in the 1670s eventually appearing in the 12-volume Hortus Malabaricus (1678->)

1638-1715 Pierre Magnol – France, Montpellier – Taxonomy – Professor of Botany and Director of the Botanc Gardens at Montpellier, the first University to establish a botanic garden in France. He was a member of the French Academy. In 1687 he became king’s physician. Well known for his natural system of plant classification and the first derivation of the plant family as we know it today as presented in his Prodromus historiae generalis plantarum, in quo familiae plantarum per tabulas disponuntur (1689). In 1676 and 1686 he produced a list of plants growing around Montpellier and in 1697 a Hortus regius Monspeliense or catalogue of plants in the royal garden of Montpellier

1641-1712 Nehemiah Grew – England – Anatomy, Physiology – A clergyman educated at Cambridge University and Leiden The Anatomy of Vegetables Begun (1670) sufficient to make him a Fellow of the Royal Society. His major work Anatomy of Plants (1682) combined his anatomical and morphological research with 82 plates, describing pollen in detail for the first time and prompting him to be called the ‘Father of Anatomy’. Along with Italian Malpighi he pioneered the field of plant anatomy

1656–1708 Joseph Pitton de Tournefort – France, Paris – Taxonomy – A clear idea of genera Institutiones Rei Herbariae (1700) classifies c. 9000 species into 698 genera and 22 classes; the basis of French plant taxonomy where the Linnaean system was never fully accepted. His system was based on morphological characters pf the flowers and adopted widely in Europe until superseded by that of De Jussieu and only improved by that of Ray

1659-1728 William Sherard was a taxonomist and, like his contemporary John Ray, of humble origin, working hard and gaining a place at Oxford university from 1677 to 1683, then studying botany in Paris from 1686 to 1688 with Joseph Pitton de Tournefort before studying under Paul Hermann in Leyden (who had also studied with Tournefort) from 1688 to 1689. In 1690 he served as a tutor in Ireland before taking a post as British Consul at Smyrna from 1703 to 1716 becoming wealthy enough to become a patron of naturalists that included Johann Jacob Dillenius, Pietro Antonio Micheli, Paolo Boccone and Mark Catesby and ensuring the publication of Sebastien Vaillant’s Botanicon parisiense (1727) and Hermann’s Musaeum zeylanica. An endowment was given for the Chair of Botany at Oxford University with the stipulation that it be given to Dillenius who, upon William’s death, was appointed the first Sherardian Professor of Botany. Sherard contributed to John Ray’s Stirpium . . . (1694), Paul Hermann’s Paradisus Batavus (1698) and, after 1700, continued, though never completed, Caspar Bauhin’s Pinax . . .. Dillenius’s Hortus Elthamensis frequently cited by Linnaeus, described rare plants grown in the garden of William’s brother James Sherard in Eltham, Kent.

1660-1753 Hans Sloane – A physician-botanist and dilletante natural scientist who studied medicine first in London then Paris with Tournefort and Montpellier with Magnol, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1685 when aged 24. In 1687 he travelled to the West Indies accumulating a herbarium of about 800 species and publishing his Catalogue . . . of these plants in 1696 using Ray’s system. He is said to have introduced the idea of drinking chocolate. In 1689 he commenced practice in Bloomsbury as a society physician and served three successive sovereigns, Queen Anne, George I, and George II. He was president of the Royal Society from 1727 to 1741 bequeathing his collection, which now included the purchased herbaria of many other botanists, to the nation for £20,000. It is one of the world’s greatest pre-Linnaean collections and includes many priceless manuscripts. The government purchased Montagu House where the collections were stored, and this formed the core of the later British Museum, British Library and the Natural History Museum

c. 1665–1718 James Petiver – a London apothecary, Fellow of the Royal Society and member of the informal Temple Coffee House Botany Club in London who exchanged plants with John Ray who called Petiver mei amicissimus (my best friend). Some of his notes and specimens were used by Linnaeus for descriptions of new species. He was also a colleague of Hans Sloane who purchased his collections which were later incorporated in the Natural History Museum

1665–1721 Rudolf Camerer (Camerarius) – Germany – Director of the Botanic Gardens at Tübingen – studied plant sexuality and provided experimental evidence for the fertilizing role of pollen which he reported in De Sexu Plantarum Epistola (Letter concerning the Sex of Plants) (1694), the first major contribution since Theophrastus’s report of sexuality in palms

Hybridization

?1667-1729 Thomas Fairchild – England, London – Plant sexuality. In 1717 was a London nurseryman and florist, a member of the Society of Gardeners formed c. 1725 and meeting every month in coffee-houses, usually Newhall’s in Chelsea and assembling an illustrated register of plants as ‘A Catalogue of Trees and Shrubs both Exotic and Domestic which are propagated for Sale in the Gardens near London.’ He corresponded with Linnaeus and advanced the study of plant reproduction by producing the first experimental interspecific hybrid between a carnation and a sweet William, known as ‘Fairchild’s Mule’. A contemporary of Phillip Miller

1668-1738 Herman Boerhaave – Holland, Leiden – Medicine – Europe’s outstanding physician during the Dutch Golden Age, holding in 1709 the Chair of Medicine and Botany at the University of Leiden which included superintendance of the botanic garden where he assembled Europe’s finest collection of exotic plants collected by, among others, the Dutch East and West India Companies

1669-1722 Sébastien Vaillant – France, Paris – Plant sexuality, morphology. He studied at Paris’s Jardin des Plantes under Tournefort, following Camerarius by specializing in the study of plant reproduction and its structures. He introduced greenhouses to France in 1714 and accepted by the Academy of Science in 1716. As demonstrator he gave a highly popular public address Discours sur la structure des fleurs was published by Boerhaave in Leiden in 1718 and secured the acceptance of the terms stamen, filament, ovary, ovule, and placentation. His Flora of Paris, Botanicon Parisiensis, was published after his death

Physiology, Mycology, Bryology

1677–1761 Stephen Hales – England – Physiology. English clergyman educated at Cambridge University made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1718 who made a major contribution to experimental plant physiology by studying transpiration and working with the chemistry of Lavoisier to measure the intake of air into plant organs observing that ’air is food for plants’, collection of gases over water, root pressure, the flow of sap, measurement of growth and a relationship between light and photosynthesis. He was buried in Westminster AbbeyVegetable Staticks

1679-1737 Pier Micheli – Italy, Pisa, Florence – Mycology, cryptogams – In 1729 Micheli wrote a pioneering account of th estructure and function of fungi together with a framework for their classification, this being widely considered as the starting point for the study of mycology

1684–1747 Johann Dillen (Dillenius) – Germany, England, Oxford – Taxonomy, cryptogams. Educated at the University of Giessen becoming Professor of Botany at Oxford. He wrote Hortus Elthamensis, an account of the plants grown in a suburb of London, in 1732 and the first monograph on mosses in 1741 which established many moss characters still in use today. Historia muscorum (1741)

1686-1758 Antoine de Jussieu – France, Paris – Taxonomy. Antoine and Bernard studied with Magnol at the University of Montpellier Antoine becoming Director of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. In 1793 he founded the Museum d’Histoire Naturelle. In 1728 he suggested a special class of plants to contain the fungi and lichens. The compendium of his and Bernard’s natural classification was published as Genera Plantarum in 1789 after his death

Plant globalization

1691-1771 Philip Miller – England, London – Plant pollination, taxonomy – As Superintendant of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Miller was instrumental in amassing of ornamental plant collections, partly following the colonial Dutch model in Leiden, Holland which preceded Britain as a European centre for horticulture

1699–1777 Bernard de Jussieu – France, Paris – Taxonomy – In 1759 the Garden of Trianon at Versailles was arranged according to his own natural system that was eventually published in 1789 as Genera Plantarum

1707-1779 Johannes Burman – Holland, Amsterdam – Taxonomy – Studied under Boerhaave at Leiden and hosted Linnaeus, introducing him to Clifford at Hartekamp. He specialized in tropical botany and the plants of Sri Lanka, Ambon and the Cape

1707–1778 Carl Linné (Carolus Linnaeus) – Sweden – Taxonomy. Linnaeus trained at Lund before moving to Uppsala as Professor of Medicine and director of the botanic garden, one of his first publications being Hortus Uplandicus (1730) a ist of plants in the garden. Linnaeus provided the intellectual resources needed to establish an ordered and internationally-accepted methodology for plant nomenclature, description, and classification much of his foundational work completed in the years 1737-1739 while in Germany and Holland. (his artificial classification system known as the ‘sexual system’) through his publications Systema Naturae (1735 in 10 editions to 1758), Fundamenta Botanica (1735) leading to PB, Critica Botanica, Genera Plantarum (1737 and later editions), Species Plantarum (1753), Philosophia Botanica (1751). His teaching produced many ‘apostles’ who travelled the world and assumed positions of botanical importance. His system of binomial nomenclature was pre-dated 100 years by the brothers Bauhin. Genera Plantarum of 1754 and Species Plantarum of 1753 together cover about 7700 species in 1105 genera

1708-1770 Georg Ehret – Germany – Trained as a gardener but becoming botanical illustrator to Anglo-Dutch collector George Clifford’s Hartekamp estate where Ehret worked with Linnaeus illustrating the famous Hortus Cliffortianus (1737). Later worked in London illustrating the novelty plants from America, Asia, and the Pacific

1719–1786 Pierre Poivre – was an 18th century French horticulturist, botanist and missionary in East Asia, travelling to the East Indies with the French East India Company in 1745. In 1760s as administrator on the French colony of Île de France (Mauritius) he founded the Pamplemousses botanical garden (now the Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden). Here (and later in the Seychelles) he grew smuggled spice plants from the Moluccas – ’20,000 nutmeg seeds and plants, then 300 clove trees’, effectively ending the Dutch monopoly of the spice trade.

Phycology

1723-1805 Pehr Osbeck – Sweden, Uppsala – Botanist – An ‘apostle’ of Linnaeus. Osbeck named the seaweed Fucus maximus (now Ecklonia maxima) in 1757 although the real scientific advance was made by Dawson Turner (1775–1858) an English banker and antiquary, and Carl Agardh (1785–1859) a Swedish bishop. More substantial research was completed in the 19th century with efforts at algal classification by Jean Lamouroux (1779–1825) and William Harvey, the latter often regarded as the first true algologist for the extent of his work and his classification of the algae into four divisions based on pigmentation

1727–1806 Michel Adanson – France, Paris – Taxonomy – advocated the use of as many characters as possible all with the same weight. Following Ray he helped firmly establish the ranks of order and family within the accepted plant classification system as set out in his 2-volume Familles des Plantes (1763,1764) which included 58 families, many the same as today

1727–1817 Nikolaus von Jaquin – Explorer – Netherlands – Studied medicine in Leiden and Paris then Vienna. Travelled to the West Indies recording local plants. Used binomial nomenclature in books on American plants in 1760 and 1763 with his own fine illustrations. Prof. botany in Hungary and Vienna

Photosynthesis

1730–1799 Jan Ingenhousz – Holland, Leuven, Leiden – Physiology – He ws made a Fellow of the Royal Society in London in 1869 and, after meeting Joseph Priestley in the 1770s he demonstrated that light is necessary for photosynthesis, that plants give off oxygen in the light and absorb carbon dioxide in the dark, and that plants, like animals, undergo cellular respiration: Experiments Upon Vegetables (1779)

1730–1799 Johann Hedwig –Germany, Leipzig – Cryptogam taxonomy, Species Muscorum Frondosorum (1782), natural classification an starting point for moss nomencature

1732-1791 Joseph Gaertner –Germany, Göttingen, Tübingen, St Petersburg, Calw – He produced detailed research on fruit & seeds De Fructibus et Seminibus Plantarum (1788-1792), recognizing endosperm as an organ of the seed

1733-1806 Joseph Kölreuter – Germany, Tübingen, Calw, Sulz – First detailed studies of plant hybridization

1739-1823 William Bartram – America – plant collector in eastern America and founder of Americ’s first botanic garden then in the 1770s through the south and Florida. Illustrated the Elements of Botany (1803-4)

1741–1805 Francis Masson – Scottish gardener who began working at Kew in the 1760s becoming the gardens’ first plant hunter sent by Banks to South Africa, Antilles, Portugal. He discovered about 500 new species

1743–1820 Joseph Banks – England – Economic botany – Though Banks completed very little academic work his administrative skills had a profound impact on the economic botany of the British Empire and, subsequently, the world

1745–1771 Sydney Parkinson – Scottish artist. The First Australian botanical artist who accompanied Banks and Solander on Cooks first circumnavigation of the world and the Pacific making hundreds of drawing but dying of dysentery on the way home. His work was published in the 1980s as Banks’s Florilegium

1746-1822 Gérard van Spaendonck – Netherlands – Botanical artist of Antwerp then Paris becoming in 1774 a miniature painter in the court of Louis XVI then Prof. Flower Painting at the Jardin du Roi where he taught Redouté and contributing to the collection Vélins du Roi. His most famous work was Fleurs Dessinées d’Aprés Nature (Flowers Drawn from Life) (1799-1801)

1749–1832 Johann Goethe –Germany, Leipzig, Strasbourg – Morphological development – In Die Metamorphose der Pflanzen (1790) he speculates more lucidly than others about homology (such as the foliar nature of the floral parts), foreshadowing evolutionary thought.

1750-1816 Christian Sprengel – Germany, Halle, Berlin – Plant sexuality. He spent six years studying and illustrating the pollination of about 500 species demonstrating how finely plants were adapted to their pollinators and for cross-fertilization in what is now known as a pollination syndrome in pollination ecology

1757-1822 James Sowerby – Britain – An artist of the Royal Academy employed by France’s Charles L’Héritier in the 1780s then employed by William Curtis for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. Best known for his 36-volume, 24-year English Botany published from 1790 and containing 2592 hand-coloured engravings that set new standards in botanical illustration

1758-1796 – John Sibthorpe – studied medicine at the Universities of Edinburgh and Montpellier before following his father as Sherardian Professor of Botany at Oxford University in 1784. He assisted in the establishment of the Linnean Society in 1788, the same year as he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, and published a Flora of Oxfordshire as Flora Oxoniensis in 1794. He contributed about 3000 specimens (from two collecting trips) for a Flora Graeca seven volumes written by James E. Smith between 1806 and 1830 and a further 3 volumes prepared by John Lindley between 1833 and 1840. This 10-folio Flora, written in Latin, is one of the world’s most impressive with 966 plates of outstanding work by the pre-eminent botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer – though only 30 copies were initially produced and a few added later.

1758-1840 Franz Bauer – Germany – studied natural history and illustration and with brother Ferdinand worked at the Palace of Schonbrunn in Vienna. On moving to London he was assisted by Joseph Banks to become the first botanical artist at Kew where h eremained, becoming a member of the Royal Society and official botanical painter to King George III

1759-1828 James Edward Smith – England – son of a wealthy textile merchant, studied medicine at Edinburgh under Linnaean John Hope and established a natural history society. He then moved to St Bartholomew’s in London with an introduction to Joseph Banks from John Hope. Banks persuaded him to purchase Linnaeus’s entire natural history estate for 1000 guineas which included 14,000 plant specimens catalogued the following winter with assistance from Banks, Dryander and friend John Pitchford. Elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1786 he then went on the Grand Tour, visiting libraries and herbaria, returning to form (with Samuel Goodenough and Thomas Marsham) the Linnean Society of London in 1788 of which he was president for many years. He completed a 3-volume Flora Britannica and edited John Sibthorp’s Flora Graeca. His most popular work was Introduction to Physiological and Systematic Botany (1807). His later The English Flora was published in four volumes between 1824 and 1828. He published the 36-volume English Botany between 1791 and 1814.

1759-1840 Pierre-Joseph Redouté – Belgium – Botanical artist relieved of doing theatre sets by French botanist L’Héritier earning reputation that won his the position of court painter to Marie Antoinette then, after the Revolution to Empress Joséphine at Malmaison and famed for his work Les Roses (1817-1824). Considered the by many the greatest flower painter of all time

1760-1826 Ferdinand Bauer – Germany – studied natural history and illustration and with brother Franz worked at the Palace of Schonbrunn in Vienna and accompanying Prof. John Sibthorp of Oxford University to Greece and Turkey and illusttrating its outcome, Flora Graeca (1806-1840). Later he was artist to Matthew Flinders‘s expedition in Australia, publishing the beautiful but unsuccessful Illustrationes Flora Novae Hollandiae (1806-1813)

1765–1812 Carl Ludwig Willdenow – Germany, Berlin – Botanist, taxonomist, phytogeographer – Studied medicine and botany at the University of Halle and was Director and effectively the founder of the Botanical Garden of Berlin 1801-1812. He studied South American plants collected by explorer Alexander von Humboldt. On his death Willdenow bequeathed over 20,000 specimens to the Berlin herbarium. His main contribution was in the relation of climate to plant geography, his Grundriss der Kraűterkunde (1792) being the first attempt at floristics, a scientific account of global plant distribution. He became th first Professor of Botany at the University o Berlin in 1810, one of his pupils being Alexander von Humboldt. Other publications included a Flora of Berlin, Florae Berolinensis Prodromus (1787) and an inventory of the stock in the Berlin Botanic Gardens, Hortus Berolinensis (1816)

1767–1845 Nicolas de Saussure –Switzerland, Geneva – Physiology, photosynthesis, nitrogen absorption

1768-1819 Sydenham Edwards – English – Botanical illustrator, artist to William Curtis of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (1700 colour illustrations) but later founded his own magazine The Botanical Register, in 1815

1769–1859 Alexander von Humboldt – Germany, Berlin – Explorer, Naturalist, Plant Geographer – Brother of W. von Humboldt who founded the University of Berlin in 1807-1810 which marked the beginning of a German Golden Age in science. Travelled to New Spain for five years ( which included Venezuela, Mexico, the Andes, and Cuba) with French botanist Aimé Bonpland. Humboldt was a cult figure in an age of exploration as inland Australia, the Americas, and Africa were opened up but known botanically mostly for the plant geography he helped pioneer and the work on South America that he published with Bonpland and Kunth

1773–1858 Aimé Bonpland – France, Paris – Medicine, plant geography, exploration – Educated at the University of Paris, worked at Natural History Museum in Paris, member of the French Academy of Sciences, best known for his exploration of Latin America in 1799-1804. Superintendant of Josephine‘s garden at Malmaison. Publications included Essai sur la Geographie des Plantes (1805) and some descriptions of rare plantes at Malmaison and Navarre (1813)

1773–1858 Robert Brown – Scottish, Edinburgh, British Museum – Taxonomy. Described in detail the morphology of many plant groups his discoveries made using the microscope including descriptions of the naked ovules in gymnosperms, observation of the cell nucleus, streaming cytoplasm, and Brownian motion, pollination and fertilization, and description of many of the families and genera of Australian plants

1775-1840 Pierre Turpin – France – Amateur artist employed by French botanist Pierre Poiteau in Haiti in 1794. The leading French botanical illustrator of the early 19th century who worked for Hilaire, von Humboldt, and Bonpland

1785-1865 William Hooker- English – Plant explorer (Iceland, France, Switzerland, Italy), botanical lecturer at Glasgow in 1820, then the first official director of Kew Gardens in London in 1841, followed by his son Joseph

1786-1856 William Barton – America – Studied medicine with father Benjamin Barton, author of the first American textbook on botanical science, Elements of Botany (1803-04) illustrated by William Bartram. In 1815 appointed Professor of Botany at the Universty of Pennsylvania publishing Vegetable Materia Medica of the United States, also Floras of Philadelphia (1817) and North America (1821)

1789–1852 Joakim Schouw – Denmark, Copenhagen – Plant geography – As Professor of Botany at Copenhagen University his best known work was Grundzüge eine Allgemeinen Pflanzengeographia (1823), member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences (1841)

1796-1866 – Philipp Franz von Siebold – Germany – A German physician who worked for the Dutch government as a surgeon in the East Indies. Best known for the introduction of Western medicine to Japan where he was based for six years in the trading settlement of Dejima. He travelled to Nagasaki collecting plants and assembled a collection in both his home garden and medical school garden in Japan. When paying respects to the shogun in Edo (Tokyo) he became acquainted with Katsuragawa Hoken (Wilhelm Botanicus) a talented botanical artist and physician to the shogun and botanist and companion collector Keisuke Ito. He returned to Europe to live in Leiden where he produced three books revealing Japan to the West: Nippon (1832-1858), Fauna Japonica (1833-1850) and Flora Japonica ((1835-1842), the latter with German botanist Joseph Zuccarini. He trialled edible Japanese plants in the Leiden botanical garden and returned to Japan in 1859 collecting avidly and returning plants to Leiden. He had introduced over 800 species new species to Europe.

1799-1871 Anna Atkins – England – botany, botanical art – Refined early photographic printing techniques (the cyanotype or ‘blueprint’) for, first seaweeds, then ferns and eventually flowering plants. With her father as librarian at the British Museum and Secretary of the Royal Society Anna managed to forge her own path of scientific interest becoming an accomplished artist and joining the Botanical Society of London. Frustrated by the lack of illustrations in William Harvey’s groundbreaking Manual of the British Algae (1841) she produced her own set consisting of 398 plates as the first book in the world (3 vols from 1843 to 1853) illustrated with photographs. There followed Cyanotypes of British and Foreign FernsCyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns (1854).[13]

1799-1865 John Lindley – England, London – Botany, taxonomy – An important public figure in Victorian botany and horticulture and a prolific worker, editing and contributing substantially to the general horticultural and botanical literature, with a passion for orchids: a colleague of William Hooker, Robert Brown and Joseph Banks, the latter employing him in his library and herbarium in Soho Square. He preferred the ‘natural system’ of Frenchman Antoine de Jussieu to Linnaeus’s artificial system. He published a Synopsis of the British Flora (1829) the most complete natural system following the work of Linnaeus Introduction to the Natural System of Botany (1830), available in English (he had become the first Professor of Botany at the University of London in 1829) and it was subsequently adopted in both Britain and America. There was also The Fossil Flora of Great Britain (1831-1837) and a contribution of 16,712 descriptions to John Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Plants (1829), the popular Ladies’ Botany (2 vols 1837-8), but most popular of all, his Elements of botany (1841). His books founded the RHS Lindley Library. In 1838, with Kew struggling, he wrote a submission for its development as a key botanical institution.

1800-1884 George Bentham –England, London – With Joseph Hooker at Kew he produced the last major natural classification of seed plants Genera Plantarum (1862-1883) with 200 families and 7569 genera described in detail. He wrote many monographs and a Handbook of the British Flora (1858) and with Ferdinand Mueller Flora Australiensis (1863-1878)

Cell theory, modern plant science

1804–1881 Matthias Schleiden – Germany, Berlin – Encouraged the transition from taxonomy to chemistry and physiology through his influential first modern textbook on scientific botany Grundzüge der Wissenschaftlichen Botanik (1842) transl. into English as Principles of Botany. He specialized in ovule formation, morphological development, microscopic structure and scientific methodology. With animal physiologist Schwann he published observations on the common structures and processes found in both animal and plant cells that launched cell theory (1849)

1805-1843 – Georgiana Molloy – English botanical collector – Worked in Swan River Colony (Perth) of Western Australia supplying specimens from one of the world’s richest botanical regions. In Augusta she created a garden, growing flowers from England and the Cape but soon adding the native wildflowers, pressing and mounting many of these. She met Lady Stirling, wife of the Governor of Western Australia whose cousin, James Mangles asked Georgiana to send specimens to him in England, especially seeds. She built up large collection of about 1000 carefully prepared and described, which were sent to Mangles and then distributed to eminent scientists and horticulturists such as Paxton and the Loddiges nursery, impressing John Lindley who praised her efforts in the appendix of Edwards’s Botanical Register[14]

1805–1877 Alexander Braun –German, Freiberg, Giessen, Berlin – Morphology, cell theory, phyllostaxis – After studying at Heidelberg, Paris, Munich before becoming Professor of Botany at Freiberg (1846), Giessen (1850) and Berlin (1851)

1806–1893 Augustine de Candolle – Switzerland, Geneva – Taxonomy. Studied in Paris with Desfontaines and produced a new Flore Franҫoise, from 1808-1816 Professor of Botany at Montpellier producing Théorie élementaire … (1813) in which he coined the word ‘taxonomy’, before moving to Geneva to work on his Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis, a compendium attempting to include all known seed plants classified and described in 17 volumes, the last 10 by other authors (35 in all) and published by his son Alphonse (1823-1873); it included 58,000 species in 161 families. It was classified using an advance on the system of De Jussieu. Those using De Candolle’s system or modifications of it included John Lindley(1799-1865), A. Brongniart (1801-1876) and S. Endlicher (1805-1849)

1809-1882 Charles Darwin – Englishman – his On the Origin of Species (1859) would have a profound influence on all biology