Coffee

Image: Roger Spencer – 2016

Coffee – Coffea arabica (to a lesser extent C. canephora and C. liberica)

Coffee, brewed from ground roasted coffee beans, is served either black or with milk as a slightly acidic aromatic and flavoursome mild stimulant. The history of coffee follows the modern era being strongly linked to the Age of Discovery but has stronger associations with the Age of Reason. Like Beer and tea it is a ‘safe’ drink whose processing requires the use of boiled water.

Many people both historically and today drink coffee as an alternative to alcohol – indeed, it is mistakenly believed to be an antidote to the effects of excessive alcohol consumption.[1]

Origin

The species of coffee that is used for drinking grows naturally on the Ethiopian massif and Arabian peninsula where many legends tell of its discovery, properties, and first use as a drink. Among them the observation that sheep become skittish after eating the berries that are the source of coffee beans and that drying and boiling them was found to have a similar effect on the human body; or of the man Omar banished to the desert near the city of Mocha in Yemen who, after eating the red cherry-like berries, found sufficient energy to return home. The leaves have been an Ethiopian masticatory since ancient times.[5]

The plant & processing

Common Coffee, Coffea arabica is an evergreen shrub reaching no more than 5 m tall, native to the Old World tropics. The botanical name was applied by Swedish botanist Linnaeus in 1753, is in the botanical family Rubiaceae and native to tropical Africa, mainly Ethiopia. Though generally grown for its commercial value it has attractive flowers and red berry pulpy fruits. Propagation is by ripe wood cuttings although in the tropics the pulp is removed and the seeds grown. There are a a wide range of variants and commercial cultivars. Almost all commercial coffee is derived from this species but C. liberica and C. canephora are also sometimes grown. The beans are extracted from the berry pulp and roasted before being brewed in various ways.

Use in Arabia

Certainly it appears that it was in Yemen, on southwestern Arabian peninsula, that provide the first firm records of coffee as a popular drink: they date to the mid-fifteenth century. Sufis used coffee to hold off sleep during long religious ceremonies that continued deep into the night. From Yemen the drink had passed to Mecca and Cairo by 1510 and became a drink sold on the streets and coffeehouses and having the special appeal that it was non-alcoholic, which was important for the Muslim faith, although its effect as a stimulant was of concern to some scholars. There was also concern about coffeehouses as potential sources of gambling and political unrest.

Arabia remained the major source of coffee until the end of the seventeeth century. Harvested near Mecca the beans were transported to the port of Jiddah where they were shipped to Suez, then carried by camel trains to warehouses in Egypt’s Alexandria where they were subsequently shipped around the Mediterranean by French and Venician merchants. It was being sold in Constantinople in 1550 and Venice in 1616. By 1675 there were about 3000 coffee houses in England.[5]

Arab monopoly

Coffee, like spices in the seventeenth century, were monopolised at source by Arab traders. Attempts were therefore soon made to break the monopoly. The Dutch managed to pillage coffee plants, raising cuttings in glasshouses Amsterdam before the Dutch East India Company took the plants to the Dutch East Indies where they were successfully cultivated in Java and transported directly to Rotterdam, and since Arabian coffee could not compete the monopoly was effectively transferred to Holland.[4]

Arab coffee preparation involves boiling three times which achieves maximum extraction and a strong black product.

French naval officer Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, from Martinique, determined to set up plantations in the West Indies and in 1723 obtained cuttings from a plant growing in a greenhouse of Paris’s Jardin des Plantes (via a lady acquainted with the king’s physician who was allowed to access any plants for medicinal purposes) under the care of famed botanist De Jussieu. The plant had been sent to Louis XIV as a gift from the Dutch government in 1714, the plant itself derived in turn from one sent to the Amsterdam Botanic Gardens from Java in 1706. He successfully transported and grew the plant in Martinique, sending cuttings to other places including San Domingo and Guadeloupe with export of beans to France beginning in 1730 while, at the same time, the Dutch introduced plants to Suriname (1718), a Dutch colony in South America, and subsequently Cayenne (1722) and Brazil (1727), Jamaica (1730). Other cuttings, all probably progeny of Clieu’s original plant, went to Costa Rica, Cuba, Haiti, and Venezuela, Philippines (1840) and Hawaii (1825). Brazil is today’s major producer.[6]

Coffee arrives in Europe & America

Europeans visiting Arabia in the early seventeenth century noted the way that coffeehouses acted as community centres for processing news, like the European taverns. Being a Muslim drink coffee attracted suspicion from Christians. In about 1605 Pope Clement VIII (1536-1605) was asked to clarify the Catholic position on coffee. After sipping a drink and inhaling its aroma he declared that it would be an acceptable Christian drink too. The precise date of introduction to Europe is unclear but it seems Venitian merchants may have opened a coffeehouse in Venice in 1629 and Rome in 1645.(see Wikipedia) By the 1650s coffee houses had appeared in London and within a decade they could also be seen in Amsterdam and the Hague.

The first major commercial shipments were conveyed to Europe by the Dutch East India company which later attempted to develop its own plantations in Java in 1690[6] (but were more successful with new introductions in 1699) and Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka).

In Germany’s Leipzig Georg Philipp Telemann had, in 1702, formed a musical ensemble called Collegium Musicum which was based at Zimmermann’s Coffee House. Johann Sebastian Bach succeeded Telemann as Director of this ensemble. Generally associated with church music, Bach also composed the ‘secular cantatas’, the Coffee Cantata probably first performed in the coffeehouse sometime between 1732 and 1735.[3]

France’s Café Procope (est. 1686) in Paris was the meeting place of French Enlightenment savants like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot, and still stands today.

In America the strategy for the dumping of tea in Boston harbour at the ‘Boston Tea Party’ (see Tea) of 1773 was hatched in Boston’s Green Dragon coffeehouse and coffee has been more popular than tea ever since. The American Declaration of Independence (1776) was first publicly announced at Philadelphia’s Merchant Coffee House.

Coffee and the British Empire

The first coffee house to be opened in western Europe was opened in Oxford in 1650, two years before that of Turkish proprietor Pasqua Rosee in London and four years before the Queen’s Lane Coffee House (est. 1654) which is still doing business today.

London’s first coffeehouses opened at about the time of the puritan revolution of Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658). Charles I was beheaded in 1649 and with the English Civil War (1642–1651) now over the new coffeehouses provided temperate meeting places for those not wishing to be associated with the consumption of alcohol. Some coffeehouses sported quality furniture, even bookshelves, so they were a classy alternative to the rough spitooned taverns, although they were notorious for the puther creted by smokers. As imperial commerce gathered momentum these orderly surroundings were appropriate for business contracts – although there was also room for political plotting and intrigue.

England’s first coffeehouse was opened in Oxford in 1652 predating by a couple of years London’s first coffeehouse in St Michael’s Alley, Cornhill. London’s first coffeehouse opened in 1652. By 1663 London had accumulated 83 although this surge in initial interest was tempered when many were burned down in the Great fire of London in 1666.[2] There were the dissenters who disliked the potential of such places for sedition and there was the problem that, from their start, coffeehouses were men-only establishments.

Between 1680 and 1730 London became the European coffee Mecca. Seventeenth century coffeehouses were communication hubs for politicians, scientists, businessmen, and the literati. Like today’s internet this information was available on a wide range of subjects and often unreliable or politically motivated. As information centres coffeehouses would provide newspapers, pamphlets, and advertising material to peruse over your coffee. In London, for example, there was the London Gazette (est. 1665), Daily Courant (est. 1702 as the first daily newspaper and it included translations from foreign newspapers), The Flying Post (a Whig broadsheet est. 1695), The Post-Boy (a Tory broadsheet est. 1695), Tatler (est. 1709), The Spectator (est. 1711) and many others. This was an opportunity for cartoons, political satire, and what was called ‘coffeehouse wit’. Foreign newspapers, the latest stock prices, shipping lists, or other broadsheets were displayed on walls, depending on the interests of clientele. Facilities often included meeting rooms, libraries, auction rooms, and shops. The Penny Post, established in 1680, was the first postal delivery service in London, it had a uniform rate of one penny for letters and packages weighing up to 1 pound and coffee houses were convenient mailing addresses for their regular customers. Indeed, coffee houses as sources of learning were sometimes called ‘penny universities’ since that was usually the charge for a dish of coffee at this time.

By 1700 in London individual coffeehouses or districts became associated with clientele of particular interest groups: scientists (the Grecian Coffee House), businessmen (around the Royal exchange), poets and playwrights (Will’s Coffee House at Covent garden), ship owners and insurers (Lloyds which morphed into today’s insurers Lloyds of London), the politically active (St James & Westminster), clergymen (near St Paul’s Cathedral) and so on.

The Financial Revolution

During the 1690s the number of listed companies increased rapidly from 15 to 150 with stocks traded like other goods at the Royal Exchange. But when the government began to regulate trading the brokers moved to Jonathan’s Coffee House in Exchange Alley. The group moved into a new coffeehouse in Lombard Street called Jonathan Miles’s Coffee House then, in 1773, The Stock Exchange, the precursor to today’s London Stock Exchange.

These changes would have far-reaching consequences. The new buying and selling of shares in joint stock companies, development of expensive insurance schemes, the public financing of government debt to fund costly colonial wars would be a crucial aspect of British imperial ascendancy. With the decline of Dutch world power Amsterdam was replaced by London as the financial centre of the world. Pivotal to this phases of British economics was the publication of Scotsman Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776) which advocated minimal government interference in economic matters because the ‘invisible hand of the market’ would, without regulation, optimally adjust prices according to supply and demand. Much of this seminal work was written in The British Coffee House (est. 1722), a favourite haunt of Scottish intellectuals.(S.pp. 163-165)

The French Revolution

Enlightenment France applied reason and science to the political sphere arguing the illogicality of absolute monarchy, the claim that royal power is sanctified by god. A French satirical polemicist known under the pen-name Voltaire used his penetrating intellect to attack entrenched tradition and in so-doing upset conservatives who had him thrown into the bastille. On release he was packed off, hopefully to cause mayhem in England. Instead he fell under the thrall of English ideas – Newton’s scientific brilliance and the political ideas of empiricist philosopher John Locke. He returned to France with rebellious egalitarian thoughts concerning individual freedom and happiness which he published in Lettres Philosophiques (published in England in 1733) which was immediately banned in France the following year.

The first volume of a massive undertaking, a definitive resume of current learning following the model of Naturalis Historia (c. 77-79 CE) of Roman Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE), and known as the Encyclopédie, was launched by Diderot and d’Alembert in 1751, only to be likewise banned for its secular stance. Nevertheless its 28 volumes would be completed in secret by 1772. Diderot used the coffeehouse Café de la Régence as his base. By 1750 Paris could boast 600 coffeehouses associated with particular interests: Café Parnasse and Café Procope for literati and philosophes (even frequented by American Benjamin Franklin; actors at Café Anglais; musicians at Café Alexandre etc.(S. pp. 167-8) Aristocratic gatherings occurred in the Parisian salons but coffeehouses, as in Britain, were open to all although unlike Britain they permitted women. French government however censored both the range and content of printed news and government spies were used to sniff out sedition.

The clergy and aristocracy (the first and second estates) did not pay taxes which added fuel to popular resentment as the state attempted to recoup the cost of its support for the American Revolutionary war against Britain fought in 1775. The crisis forced Louis XVI to convene a national assembly, the first in 150 years but there was no resolution. On 12 July 1789 lawyer Camille Desmoulins is said to have initiated the French Revolution by leaping on to a table in Café de Foy, pistol in hand, yelling ‘To arms citizens! To arms!’.[8]

Association with the popularization of science

The Royal Society was formed in 1660 and after meetings the members like Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Samuel Pepys, and Edmond Halley would adjourn to Garraway’s Coffee House where experiments would be demonstrated and a lively and informal discussion was enjoyed. The Marine Coffee House near St Pauls initiated a public lecture program in mathematics in 1698, the public being allowed to view and use the latest scientific instruments, other coffee houses followed suit as science was popularized. No doubt these lectures proved more effective because they were often relevant to commercial interests – addressing practical problems to do with mining, navigation, and manufacturing.

There was generally a homely and egalitarian atmosphere, brawling was strongly discouraged.

Today

The world’s major coffee producers in 2012 were Brazil 50%, Columbia 9%, Ethiopia 8%, Honduras 6%, Peru 6%.[7]

The eighteen-century coffeehouses, on the one hand, changed into formal mens’ clubs but, on the other hand produced today’s café. ((a restaurant primarily serving coffee as well as pastries such as cakes, tarts, pies, Danish pastries, or buns. Many cafés also serve light meals such as sandwiches. European cafés often have tables on the pavement (sidewalk) as well as indoors.))

Coffee has become renowned for making fortunes for companies and traders while producers remain impoverished. At one end of the supply chain is the comfortable well-heeled latté set (you and me) and at the other the growers, pickers and labourers. Fair Trade is a twentieth century upshop of these concerns.

Coffee is now sold in a confusing conglomeration of named plant varieties, blends, milk addition of various kinds, mixtures with chocolate, and more.

Now cultivated in Africa, the Americas, India and southeast Asia and one of the most important exports of developing countries.

Associated with the internet café and the nerdy wild and sometimes challenging ideas of caffeine-fuelled computer addicts.

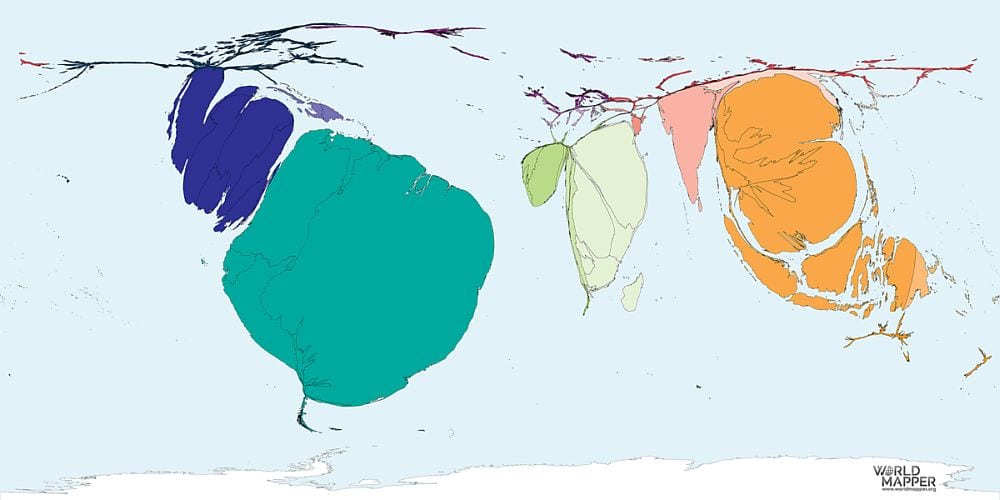

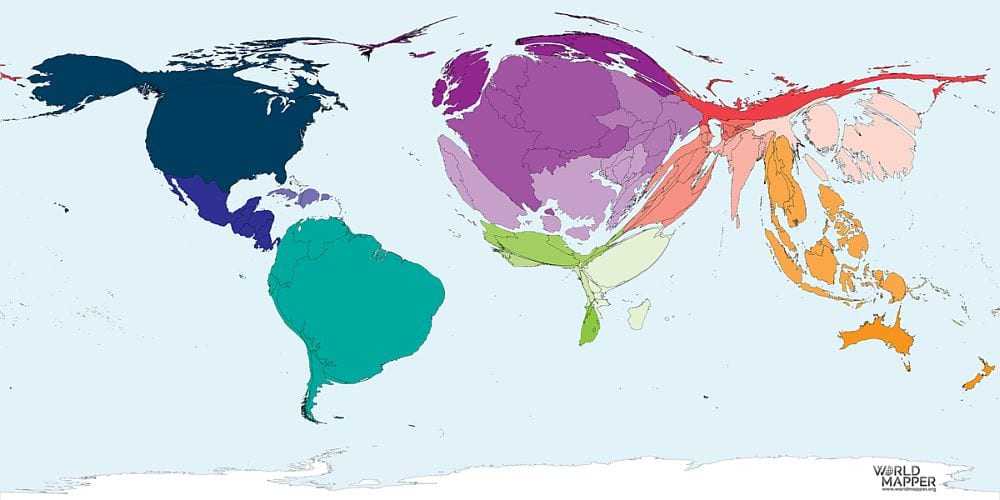

Coffee production worldwide – relative proportion by country – 2014

Data source: International Coffee Organization – March 2018

Courtesy Worldmapper.org – Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Accessed 6 July 2020

Data source: International Coffee Organization – March 2018

Courtesy Worldmapper.org – Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Accessed 6 July 2020

Timeline

c. 1450 – Recorded as a popular drink in Yemen

c.1510 – available in Mecca and Cairo

1605 – Pope Clement VIII declares coffee acceptable to Christians

1652 – First coffeehouse opened in London. By 1663 the number reaching 83

1660s – First coffeehouses in Amsterdam and the Hague; by 1663 London has 83

1671 – France’s first coffeehouse opens in Marseilles but by 1700 many had opened

1680-1730 – London becomes the world’s coffee hub

1722 – The British Coffee House established, where Scottish intellectuals would meet and Adam Smith would write his Wealth of Nations

1732-1735 – Johann Sebastian Bach composes the Coffee Cantata

1750 – Paris has 600 Coffeehouses

1773 – Strategy for the Boston tea Party hatched in Boston’s Green Dragon Coffee House

1776 – American Declaration of Independance first announced in Philadelphia’s Merchant Coffee House