Biological agency – test

Carter – test no action required.

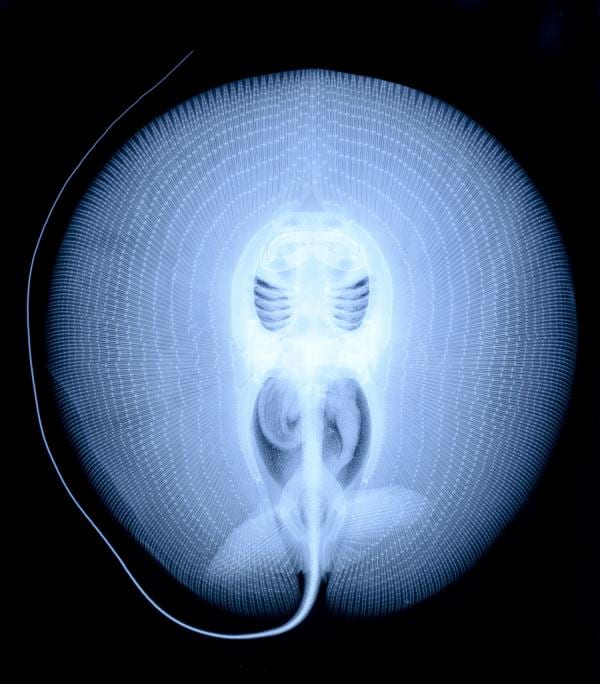

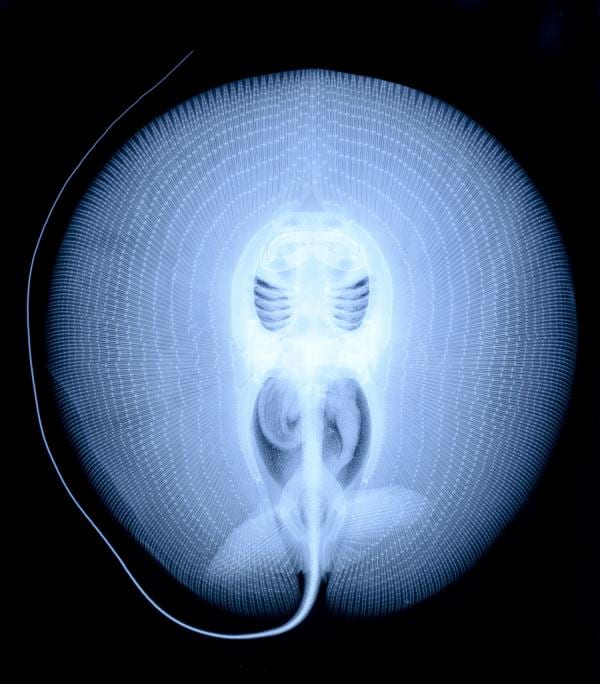

The stingray is a biological agent. As an individual organism it is a physically bounded and functionally integrated unit of life with an autonomous agency. The structures, processes, and behaviors of the stingray are unified in their support of the flexible, adaptive, and goal-directed behavior of the organism as a whole as it acts on, and responds to, its conditions of existence.

Goal-directed behavior in biology is agential and purposive behavior – it is behavior that has natural limits or ends. These ends are causally transparent and without mystery; they do not necessarily imply supernatural influence, conscious intention, or backward causation.

Stingray behavior expresses many proximate goals but these are subordinate to the universal, objective, and ultimate goals of all organisms – the propensity to survive, reproduce, adapt, and evolve – as necessary conditions for biological agency. They are universal because they are expressed by all organisms; objective because they are a mind-independent empirical fact; and ultimate because they are a summation, unification, and limit for all proximate goals.[77]

The intricate and evolving design of functionally organized organisms exceeds human ingenuity. This design was generated by the agency of non-cognitive goal-directed behavior, the same non-cognitive agency that, through a long evolutionary process, gave rise to the human body, human brain, and human subjectivity.

Organisms, as paradigmatic biological agents, are information processors with a behavioral orientation (the propensity to persist by self-replication and the capacity for flexible adaptation to their conditions of existence). These agential characteristics are what most obviously distinguish organisms from inanimate objects and the dead. When science ignores the universal and purposive goals of biological agency, life assumes the character of inanimate matter, of purposeless physics and chemistry, and biology becomes a goalless collection of unrelated facts.

Aristotle established biological agency (telos) as the driver or cause (the explanatory end) of biological activity and therefore the most appropriate necessary and sufficient defining condition for life. Aristotle’s agency was an animating principle for life, but it did not address the question of evolutionary change. This was provided later by Darwin’s account of natural selection. Aristotle described the necessary agency required to drive both life and evolution: Darwin described the mechanism of evolutionary change.

The Modern Synthesis is a detailed account of the mechanism of evolution based on gene frequencies in populations. The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis enriches Darwin’s account by acknowledging both Aristotelian agency and its dispersion through organismal structures, processes, and behaviors rather than being located uniquely in genes.

Human agency is a highly evolved and cognitive form of universal biological agency.

Shared X-Ray image of a stingray by loctrizzle

‘Why should the phenomenon that demarcates the domain of biology be off-limits to biology?’

Denis Walsh – 2018, p. ix

‘To the extent that an evolved organism is well-adapted to its environment and thus equipped with phenotypic traits that enhance its survival and reproduction it can be validly treated as agent-like as long as a certain empirical precondition is met, at least approximately. This is the unity-of-purpose condition: the organism’s traits must have evolved because of their contribution to a single overall goal, so have complementary rather than antagonistic functions. To the extent that this is not so, it ceases to be possible to think of the organism as agent-like.’ [Okasha treats ‘unity of purpose’, following evolutionary biology tradition, as fitness-maximization]

Samir Okasha – 2020, p. 230

‘A minimal account of biological agency must describe, in the most parsimonious and scientifically acceptable terms, what constitutes a biological agent, its goals, and its means of achieving these goals.’

PlantsPeoplePlanet – October 2023

‘Biological agency emerged from the universe as a novel property when matter became organized into functionally integrated units (organisms) with the propensity to survive, reproduce, adapt, and evolve. [102]

For autonomous organisms to pursue goals three critical conditions, or means, must be in place: a behavioral orientation (an overall goal, purpose, value, perspective, or point of view); the capacity to process information; and the ability to adapt to its conditions of existence. This non-cognitive inherited agential disposition was the evolutionary to precursor to human cognitive agency and the miracle of matter that is aware of itself.

PlantsPeoplePlanet – November 2023 (modified 21 March 2024)

This article is one of a series investigating biological agency and its relationship to human agency. These articles are introduced in the article on biological explanation. Much of the discussion revolves around the scientific appreciation and accommodation of real (genetically inherited) but mindless (non-cognitive, ?teleonomic) goal-directedness (agency) that is a universal feature of life. Biological agency is treated as having cognitive and non-cognitive (pre-cognitive) components. The non-cognitive agential traits, as evolutionary precursors to cognitive traits, are referred to here using the general term pre-cognition. While it is currently conventional to treat biological agency as a human creation - the reading of human intention into nature - this website explores the claim that it was non-cognitive biological agency that ‘created’ human bodies and human subjectivity.

The suite of articles on this topic include: What is life? - the crucial role of agency in determining purposes, values, and what it is to be alive; Purpose - the history of the notion of purpose (teleology) including eight modes (claimed sources of purpose) in biology ; Biological agency - an investigtion of the nature of biological agency; Human-talk - the application of human terms, especially cognitive terms, to non-human organisms; Being like-minded - the way our understanding of the minded agency of human intention is grounded in evolutionary characteristics inherited from biological agency; Biological values - the grounding of biological values, including human morality, in organismal behavioral propensities (biological normativity); Evolution of biological agency - the actual evolutionary emergence of human agency out of biological agency; Plant sense and Plant intelligence addressing the rapidly developing research field of pre-cognitive agency in plants.

Describing real but non-cognitive agential biological traits (goal-directed behavior) using the language of human cognition results in cognitive metaphor. This has created profound philosophical and semantic confusion (see human-talk). Formal scientific recognition of pre-cognitive biological agency is, therefore, a combined philosophical, linguistic, and scientific challenge. Though word meanings cannot be changed at will, in science it is possible to refine categories and concepts to better represent the world.[73] It is being increasingly acknowledged that human agency is a limited, specialized, and highly evolved form of more general biological agency. However, without a formally developed and descriptive technical terminology, the agential properties of organisms are frequently described using language conventionally restricted to human agency – essentially the language of human cognition and intentional psychology. Thus, the increasing scientific application of words like ‘agency’, ‘purpose’, ‘cognition’, ‘intelligence’, ‘reason’, ‘memory’, and ‘learning’ across biology is broadening their conventional semantic range to include all organisms, and the treatment of such usage as cognitive metaphor is declining.

For a summary of the findings and claims made in these articles see the evolving article called biological desiderata.

Introduction

Agency, as activity and influence, is everywhere.

Aristotle believed that philosophy must provide an account of change, and this was one of his major philosophical endeavors. What is it that generates activity in the universe and has causal efficacy . . . what makes things happen? The universe must have had a prime mover, or first cause that gets everything going.

Today’s science tells us that we live in a universe with a default condition of flux. People, mountains, and stars are all just temporary manifestations, ephemeral concentrations of stuff in the vast swirl of cosmic time. Life itself is a glaring example of a brief and dynamic process. So, the crucial question has now become . . . how do we account for stability, permanence, stasis, and our need for the enduring security of ‘things’? How can we talk of rocks, trees, genes, and molecules as if they were eternal?

Nature, in a broad sense, is full of powerful and terrifying forces (agencies): earthquakes, tsunamis, storms of thunder and lightning, fiery conflagrations, floods, plagues, famines, and disease. Who or what is the agency behind all these phenomena? Change can imply a mysterious, possibly supernatural force of some kind, so it is hardly surprising that we personify nature by attributing such events to punishing and rewarding human-like Gods.

The history of science can be understood as a progressive exorcism of agential spooks. It has always struggled with the intangibility of natural forces which are difficult to explain because they cannot be seen, smelled, heard, or touched, even those of foundational physics. Some forces, for example, have an immaterial and mysterious capacity to act at a distance – which is especially spooky. Newton accounted for the effects of gravitation while refusing to speculate on what it was, and only relatively recently have we come to grips with the strange invisible attractive phenomena associated with electro-magnetism, while finding new puzzles like quantum entanglement.

There are agents of all kinds in the world, but how are we to understand the notion of agency in biology? More specifically, what is it that animates living things – that gives them ‘life’? What exactly is the drive and ‘vitality’ that so obviously leaves a body when it dies?

When our scientific predecessors treated the goal-directed biological agency of non-cognitive organisms as a creation of the human mind, they were treating biological agency like all the other spooks, as something with no mind-independent existence. They may have exorcised one spook too many.

The idea of agency in biology has its origins in Aristotle’s telos (hence teleology) – his investigation of the ‘final causes’, ‘ends’, or ‘purposes’ of things – his ‘that for which‘.

In his treatise ‘On the soul’ (De Anima) Aristotle described the soul[79] as a principle of life and individuation – a goal-directed and internally derived animating principle that organizes the matter of living bodies in a manner that distinguished them from inanimate objects. His concept of the soul corresponds closely with what, today, we call agency. Though Aristotle pointed out that his principle was not independent of the body, interpreters have tended to treat it as a philosophically ambiguous or supernatural force.

Later, influential Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant, while endorsing Aristotle’s views concerning the inner source of functional organization in self-organizing beings, regarded this as an as if (what he called ‘regulative’) necessity of explanation, rather than something that actually existed in nature. It is this Kantian view of biological purpose and agency as a metaphor or heuristic that still holds sway today.

Aristotle

Considered the founder of biological science, Aristotle noticed how, in the biological world especially, explanations of organisms – including, their structures, processes, and behaviors – became dissociated facts unless the question ‘what is it for‘ was answered. This was a cogent question precisely because all organisms are goal-directed (agential, purposive) in a way that inanimate objects are not. It makes sense to ask what an eye or a wing is ‘for’, when the same question asked about a rock, or the moon seems like nonsense.

Teleology has a vast literature and the article on purpose provides an introduction to its history, literature, and contest of ideas, including eight different proposed sources of purpose in the world.

Aristotle’s teleology (specifically his formal and final causes) was rejected by the Scientific Revolution because it seemed philosophically obscure with the goals of organisms exerting a mysterious and unscientific causal pull from the future. These goals were like strange supernatural forces that were not amenable to empirical investigation. Moreover, they could be convincingly explained as the reading of human intentions and aspirations into goal-less matter. These philosophical difficulties were compounded by a pre-Darwinian anthropocentrism that understood organisms as the unique products of Special Creation by God not, as Darwin later claimed, connected by evolutionary descent with modification from common ancestors.

Aristotle’s logic and philosophical rigor had overlooked the scientific value of experiment and observation, and it was this that was avidly embraced by the Scientific Revolution. Credibility for the revolutionary new scientific empiricism was gained, in part, by a rejection of the old sources of authoritative knowledge, the Bible and Aristotelian philosophy. Exorcising strange out-of-body forces from non-human organisms was considered a scientific duty. Francis Bacon, who headed the charge against Aristotelian teleology, called Aristotle’s final causes ‘barren virgins dedicated to God‘.

The Scientific Revolution’s interpretation of biological agency and purpose as the reading of human cognitive sentiments into non-human organisms (like Kant’s heuristic interpretation) has persisted to the present day. Its philosophical and scientific ramifications are discussed in detail in the articles listed at the head of this page.

Seemingly a semantic problem, this is a metaphysical debate concerning the reality or not of purpose and agency in organisms.

Over the last few centuries, the objections to teleology (its implication of backward causation, inference to the supernatural, anthropomorphism, and philosophical obscurity) have all been met with compelling refutations, so the time is now right to examine how biology looks when, once again, it accepts Aristotle’s vision of the subject as he presented it over 2000 years ago – a vision of biology saturated with functions and goals – of life suffused with agency, where ‘nature does nothing in vain‘.

Darwin

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant, like Aristotle, had recognized that the teleology of machines was extrinsic (derived externally) while the purposive nature of self-organizing biological structures, processes, and behaviors was an intrinsic teleology. However, it was customary at this time to study and explain the obvious goal-directedness of nature by reference to the purposive wisdom of an external supernatural Creator. This was, for example, the natural theology followed by Linnaeus and made famous by clergyman William Paley.[108] The possibility of mindless (non-cognitive) purpose and agency was not countenanced at a time when people believed that these were properties breathed into humans by God at the Creation. Darwin was uncommitted in his views about purpose (teleology) in nature (see Charles Darwin).

Darwin provided a causally transparent mechanism for evolution. It was assumed that his theory of natural selection had removed any need for not only supernatural explanations of life but also all talk of agency and purpose in biological systems. When we explain the mechanical operations of the heavens there is no necessity to add the complications of purpose and agency. If, then, we provide a mechanical account of evolution are purpose and agency equally dispensable?

The purpose we attribute to organisms derives from their goal-directed agential behavior, a natural feature that is absent from the lifeless heavens. In providing a mechanical explanation of evolution, Darwin did not explain purpose and agency away.

While Darwin’s theory of natural selection provided a scientifically compelling account of the origin of species, it lacked a fleshed-out empirical account of the mechanism of inheritance. With the development of genetics, and specifically population genetics in the 1920s, and the cracking of the genetic code in 1953, evolutionary explanation took on a gene-based character now known as the Modern Synthesis or Neo-Darwinism. The overwhelming explanatory power of genetics and the genetic code seemed to put a final nail in the coffin of agency and purpose.

The assumption that biology is grounded in genes, with organisms the epiphenomena of genetic programs, occurred during a historical phase of 20th-century analytic and reductionist exuberance that is now drawing to a close.

There has, in recent times, been a lack of conceptual synthesis in biology, probably due in part to the increasing isolation and proliferation of new and developing biological subdisciplines in the microbiological and cognitive sciences. Each discipline has carved out a unique and special place, or silo, for its own subject matter. Perhaps it is time to re-group.

Biological agency and purpose are once again acquiring respectability as science explores a new biological paradigm – the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES). This drive for a new evolutionary synthesis has unleashed a host of ambitious new perspectives on old themes including, for example, the Agency Perspective, the Philosophy of Organismal Biology, Systems Biology, Complexity Science, Enaction, Field Theory, phenotypic plasticity, niche construction, epigenetics, and so on.[58,61,62,64,66,72,74,78,86,103,104]

While goal-directed behavior is a real, indeed, obvious, and pervasive feature of living organisms, biology has never established clarity in its description of this phenomenon. The old suspicion related to Aristotle’s ‘teleology’ has prompted a 20th-century neologism ‘teleonomy’, variously defined, but recently revisited and re-defined as ‘evolved biological purposiveness.‘[69] This is like a Darwinian extension of Aristotle’s basic idea of purpose and agency but within the context of evolutionary biology.[89]

Biological agency, minimally defined as the goal-directedness of living organisms, is an obvious feature distinguishing life from non-life. Its traditional denial diminishes our scientific understanding of nature, and reduces our respect for non-human life as we perceive non-human organisms more in terms of the inanimate and purposeless world of physics and chemistry than the human world of purposive and agential intention.

Formal scientific recognition of biological agency is long overdue, but this requires an understanding of the evolving history of ideas and a close examination of what is meant by the biological agent, its mission, and its means of pursuing that mission. Above all, there must be clarity about the confusing relationship that exists between biological agency and human agency. On the genetic front there is gathering evidence, in a range of disciplines, for the inheritance of acquired characteristics, a Lamarckian idea that was once lampooned but now also gathering respectability. The exploration of these ideas is likely to involve a protracted period of discussion in the scientific literature unless expedited by a formal process addressing problems of terminology, definitions, principles, etc.

These are the questions that biologists and philosophers are currently investigating as they reconsider the foundations of the study of life.

Before Darwin, there was no scientific explanation for the goal-directedness in nature that was so evident to everyone. Who, or what, put this purposiveness into living things? For most people there was only one answer, God.

Darwin combined heritability, genetic variation, differential reproduction, adaptation to the environment, selection pressures, and random events to produce the gradual change of species that was necessary to generate the entire community of life. He provided a compelling naturalistic (scientific, mechanistic) explanation of evolution that did not depend on supernatural intervention and in so doing many believed that he had, in the process, simultaneously removed any hint of purpose. But the goal-directedness so intimately associated with purpose and agency was still present, just as it had been in the first organism at the origin of life. Darwin provided a scientific explanation for purpose and agency, but he did not explain them away.

This article explores some of the logical space available within the categories ‘biological agent’, ‘biological goal’, and the ‘means’ used by biological agents to pursue their goal(s).

The Standard Model

Skepticism about agency and purpose in biology, combined with a gene-centered interpretation of evolution (the Modern Synthesis or Neo-Darwinism) are the current biological orthodoxy. This is what is referred to here as the Standard Model: it is the mainstream textbook representation of biology that developed out of the Scientific Revolution and the 20th-century genetic elaboration of Darwinian ideas. It may be characterized roughly as follows:

The concepts of agency and purpose when used in biology are best confined to the realm of uniquely human conscious intentions and rational deliberation. The agency we see in nature, and which we sometimes describe with the use of human-talk (anthropomorphism, mostly as cognitive metaphor) is our reading of human conscious intentions into organisms which, since they have no cognitive faculties, can have no intentions and therefore no agency or purpose. The attribution of agency and purpose to non-human organisms may assist biological explanation and therefore have heuristic value, but these properties are not there in reality.

There are many reasons why this interpretation of the relationship between human minds and the behavior of non-cognitive organisms is misleading: it ignores the likely evolutionary path of human cognition; it misinterprets the implications of human-talk and cognitive metaphor for biological agency; it avoids scientific and semantic confusions concerning the distinction between biological and human agency; it ignores the lack of scientific-technical vocabulary available for the description of biological agency. These matters are discussed in articles listed at the top of this page.

Combined with this suspicion of agency in biology there is a growing dissatisfaction with a mainstream gene-centric view of biology as expressed through the Modern Synthesis characterized loosely as follows:

Darwin gave no experimentally based analysis of inheritance. The genetic foundations of evolution were established much later. The Modern Synthesis combines the Darwinian theory of evolution by natural selection with modern genetics by pointing out that genetic variation within populations, driven by mutation and recombination, is the raw material for the natural selection that leads to the evolution of species over time. It is these genetic changes within populations that lead to the diversification and adaptation of species, so natural selection is best conceptualized as a struggle between genes, usually through the effects they have on organisms, and for their replication and transmission to the next generation. The primacy of genes derives from the fact that evolutionary novelty can only occur when genetic information passes from germ cells to somatic cells and not vice-versa – that is, there is no inheritance of acquired characteristics – changes in somatic cells are not passed on to offspring.

This emphasis on genes not only ignores the role of biological agency and behavior in evolution, it also ignores many other non-genetic factors that can influence the evolution of species.

Problems with the Standard Model

Biology is currently undergoing a paradigm shift in philosophy as its metaphysical emphasis shifts from things to processes, the notions of purpose and agency are rejuvenated, and the reductionist model of genes ‘pulling the strings’ of life is revised.

Inversion of reasoning – there is a mistaken assumption that since biological goals can only be understood (represented) in human minds and language, then they can only exist in human minds, and are therefore a creation of human minds . . . that biological agency is therefore not real.

Reality of agency & purpose in biology – goal-directed behavior demonstrates both agency and purpose as an objective fact. All organisms express biological agency by acting on, and responding to, their conditions of existence with flexible and adaptive behavior that influences both their immediate lives and evolutionary future. The minded goal-directed behavior we associate with human agency is a cognitive evolutionary development of the mindless non-cognitive (?teleonomic) but purposive and agential behavior of mindless organisms.

Behavior & biological causation – organisms may be treated scientifically as either objects or subjects. Studied as objects their behavior is regarded in a detached way as the product of either internal or external causes such as changes in the environment or the activity of genes. This tacitly suggests internal and external causes as the primary, original, or ‘real’ source of agency and change. Studied as subjects it is clear that the behavior of organisms is always and ultimately a consequence of the internal reconciliation (functional integration at an organismal scale) between the organism’s behavioral propensities (goals) and its conditions of existence (triggers in the internal and external environments) that may help or hinder these goals. Treating the organism as a subject rather than an object converts its role from a passive recipient of impersonal causal factors to a self-determining agent. The agential reality of organisms has been known for a long time (Aristotle regarded organisms as ‘causes of themselves’; Kant recognized that ‘a thing exists as a natural end if it is cause and effect of itself’), but there have been historical changes in explanatory traditions and emphasis, at least in part resulting by a suspicion of biological agency. The underlying point remains. Behavior (which we and other organisms use to assess agency) may be indirectly triggered by internal or external causes but it is ultimately (most directly) a consequence of an internal reconciliation between an organisms natural propensities and its conditions of existence.

The metaphor fallacy – When we have no words to describe real pre-cognitive agential traits, we resort to the language of human cognition, thus condemning these traits to the figurative world of metaphor (see metaphor fallacy).

Converse reasoning – by treating the minded language of biological agency as cognitive metaphor rather than biological simile we treat biological agency as a creation of the human mind whereas in fact, and conversely, human agency evolved out of (was ‘created by’) real and mindless biological agency. Scientifically it is more productive to describe human agency as an evolutionary development of biological agency than to explain biological agency in the uniquely cognitive terms of human agency.

The mind/no mind mistake – products of biological evolution simultaneously possess – not theoretically, but in reality – both uniquely defining characteristics and characteristics that are shared with other organisms (the characteristics that indicate common ancestry). So, when locating biological objects (structures, processes, behaviors – and even biological concepts) within an evolutionary context, we must be aware that, in nature, uniquely defining characteristics are associated with other characteristics that are shared with evolutionary relatives. Biological agency and human agency are not mutually exclusive properties in the same way that organisms with minds may be considered distinct from those without minds. Human agency is just one of many evolutionary expressions of biological agency (albeit a complex and minded one) and it therefore shares universal agential features with other organisms.

Conflation of human agency & biological agency – human agency is, of necessity, an evolutionary development of biological agency. Human agency, though associated with uniquely human cognitive faculties, also shares with all organisms the ancestral propensity to survive, reproduce, and flourish. Because of this evolutionary connection, concepts we usually associate with minded agency (e.g. reason, knowledge, value) can resonate with evolutionarily antecedent properties of mindless biological agency (e.g. adaptation, information-processing, and behavioral orientation). We fail to recognize that much of the intentional language of human-talk, interpreted as cognitive metaphor, is referencing properties that exist universally in nature and are physically expressed by degree.

Anthropocentrism – consider the sentence:

The design we see in nature is only apparent design

Insisting that ‘agency’ and ‘purpose’ are strictly cognitive concepts is a form of anthropocentrism. We say that design in nature is only apparent design (not real) because it is not human design, it has not been created by human minds. But nature and organisms are replete with (real) designed structures that are far more complex, beautiful, and ordered than anything produced by humans. Mindless nature created/designed the human body, and the human brain with its capacity to contemplate itself.

The problem is that, for many people, words like ‘design’ (and other words like ‘purpose’, ‘reason’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘value’, even ‘creation’) are only meaningful in the context of human cognitive faculties. Organisms cannot manifest design because they have no cognitive faculties.

But here lies the intellectual challenge of the cognitive metaphor. Because nature’s mindedness is unreal (hence the cognitive metaphor) this does not mean that the design is unreal. Our anthropocentrism simply refuses to countenance the possibility of mindless design. But, following philosopher Dan Dennett’s mode of expression . . . ‘purpose’, ‘reason’, ‘knowledge’, ‘value’, ‘design’, and many other concepts attributed to human intention ‘bubbled up from the bottom, not trickled down from the top‘. That is, we would find it more scientifically productive to view human subjectivity through the real lens of biological agency than to try and understand biological agency through the metaphorical lens of human subjectivity. If we reject this form of language use then what words are we to use to describe real mind-like properties that exist objectively in nature?

The usual scientific solution to such a problem is to devise a technical vocabulary that discriminates between nature’s real and mindless design and the minded artifacts of human creation. But this has never been adequately achieved. It would be impractical and the threat to human dignity too embarrassing.

Absence of technical terminology – If words like ‘purpose’ and ‘agency’ are inappropriate for non-human (non-cognitive) organisms, then we must find some way of referring to the real goal-directed agential behavior that distinguishes this group of organisms from, on the one hand, inanimate nature and, on the other hand, those organisms with cognitive faculties. That is, we would need a new vocabulary of agential but non-cognitive terms. Introducing such a terminology seems both unwieldy and unlikely. In the meantime, we refer to real organismal agency using the language of cognitive psychology which is therefore open to the accusation of being cognitive metaphor. Real agency is thus reduced to figurative agency (see metaphor fallacy above).

Scale & the reification of hierarchical levels of organization –

The proliferation of biological disciplines over the last century, most notably those in the microbiological and cognitive sciences, has created specialized academic silos, each with its own principles, technical terms, and a sense of their crucial place within biology as a whole. Uncritical (intuitive) acceptance of the metaphor of disciplines and their subject-matter as representing the real metaphysical hierarchical organization of the biological world has reified/ontologized these ‘levels’ (both sub- and supra-organismal), investing them with an empirically and philosophically unjustified degree of independent significance. They have become equivalent levels of both reality and evolutionary selection leading to a pluralism more appropriate to inert matter than goal-directed life. It is unclear, for example, whether biology currently regards the cell, gene, organism (or none of these) as a basic unit of biological science. When each discipline claims either agential precedence or metaphysical equivalence for its own ‘level’, the scientific significance of physically bounded and functionally organized autonomous organisms is diminished or ignored.

While all scales or levels of biological organization, both structural and functional, incorporate agential, purposive, and evolutionary information, they are ultimately subordinate to the conditions determined at the scale of the autonomously integrated organism. It is the physically bounded and functionally integrated whole organism that is nature’s most clearly individuated biological agent and it is at this scale that the conditions of biological agency most obviously apply.

Process – goal-directed life is more a process than a thing. The reification of levels of organization, neglect of agency, and emphasis on genes are ways in which process can be diminished or ignored. Process philosophy reflects a dissatisfaction with the analytic and reductive notion of the unity of science as grounded in the principles and laws of maths, physics, and chemistry, built on a foundation of fundamental particles – a metaphysics that does not adequately explain the operation of complex and dynamically integrated systems and emergent phenomena, or allow for alternative perspectives on the world

Gene-centrism – the successful ‘reductionist turn’ of the last half-century – which included the cracking of the genetic code and the outstanding success of microbiology and biotechnology that followed (with associated developments in particle physics) – has, in effect, treated organisms as an epiphenomenon of the genetic code and evolution as an existential struggle between individual genes. This historical period corresponds with an ‘analytic turn’ in Western science and philosophy that has invested increasingly small constituents of the world (the parts that make wholes possible) with an unwarranted metaphysical significance as the increasingly small has been tacitly associated with the increasingly real. Since organisms are composed of fundamental particles, it is the particles, not the organism, that are given scientific and philosophical significance. Our one-time intuitive and metaphorical understanding of existence as a ladder of life dominated by the agency of gods, humans, and organisms has been challenged by an equally metaphorical assumption of the foundational metaphysical significance of fundamental particles and genes.

This reductive paradigm is now undergoing a timely revision.

Drilling into biological microstructures has sidelined factors that are now gaining more attention: it is challenging the idea that genes are the ultimate agents of life and evolution. These elements include: environmental factors that influence gene expression and phenotypic outcomes – the way organismal behavior determines the conditions of inheritance; the influence of epigenetics[75][76] on gene expression without alteration to underlying DNA, especially during development; the contribution of systems biology to the understanding of the intricate connection between genes, proteins, and other molecules with emergent properties arising from the system as a whole rather than exclusively from genes; the influence of non-coding DNA on regulatory functions including gene expression; the influence of groups and populations.

Natural selection, agency & behavior – natural selection, as propounded by Darwin, is currently regarded as the driver, cause, and foundational principle of evolution. Darwin understood natural selection as a behavioral contest which he described, following Herbert Spencer, using the expression ‘survival of the fittest’. After the analytic and genetic turn of the 20th century natural selection is today explained in genetic terms as, for example, ‘the replacement of gene variants (alleles) with those alternatives that shift the average phenotype of a population in the direction in which natural selection is tugging’ (p. 27) or, more simply, as ‘changes in gene frequencies in populations’. This characterization, while technically acceptable, ignores the behavioral arena of organisms pursuing their ultimate goals of survival, reproduction, and flourishing. Gene frequencies change in line with behaviors that generate a survival advantage – improving access to food, avoiding predators, having successful courtship, mating and parenting strategies, enhancing cooperation, coordination, learning, developing social hierarchies that contribute to reproductive success, and meeting environmental challenges. It is behavior, more than genes, that determines the environments of evolutionary adaptation that determine biological traits.

Aristotle identified the driver of life (which, after Darwin, would also become the driver of evolution) as the goal-directed behavior of organisms most parsimoniously described here as biological agency. Darwin explained the principle of its operation (natural selection) in the origin of new species, and the Modern Synthesis provided a genetic account of its mechanism through population genetics.

Evolution – How do we account for evolutionary change – what is the mechanism or driver of the changes that result in the biological process of descent with modification from common ancestors? The traditional answer to this question has been ‘natural selection’ but research over the last century or so has elaborated the answer along the following lines. Biological evolution results from changes in the genetic composition (allele frequency) in populations over time – the result of mutations (the source of genetic variation), genetic drift (random fluctuations of allele frequencies in populations due to chance events), natural selection (the process by which traits that confer a survival or reproductive advantage become more or less common in a population), and gene flow (the transfer of genetic material from one population to another over time). This is a characterization of evolution as a competition between genes.

But evolution can be characterized in other ways. A simpler account might regard evolution as the acquiring of inherited traits through the agential interaction between organisms and their conditions of existence. This is not a passive process but the product of a purposive and agential adaptive reconciliation between the natural goal-directed predisposition of organisms and those conditions of their existence that help or hinder their survival, reproduction, and flourishing. It is this short-term behavior that establishes the organism’s environment of evolutionary adaptation and therefore long-term heritable change. New species arise from the purposive and agential behavior of organisms that leads to the gradual accumulation of heritable variation within populations. This characterization is a move from a gene-centric to an organism-centric interpretation of evolution. The genetic composition of populations is not determined by the selective pressure of environments but by the behavior of organisms resulting from the inner reconciliation between their natural propensities and these environmental factors. This inner agential process shapes adaptive strategies within populations. While it is true that those genes contributing to an organism’s ability to survive and reproduce tend to become more prevalent in the population over time, the struggle for reproductive success is, in the first instance, a struggle between organisms, not a struggle between genes.

The interplay between genes, behaviors, and the environment is complicated and interconnected, but evolutionary processes are most evident in organisms and populations. While genes shape the traits of organisms, the expression of these traits and their impact on reproductive success occurs in organisms. It is organisms, through their behaviors and interactions, that are the immediate agents in the evolutionary process. The struggle for reproductive success results from competition and cooperation between organisms, and the genetic composition of populations is a result of the cumulative effects of these interactions over time.

Evolution is not, in the first instance, a competition between genes or even ‘natural se;ection’, it is a product of the agential and purposive activity of organisms in interaction with their conditions of existence.

The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis

The intellectual exploration of biology, once focused firmly on organisms, has broadened out to include populations and ecosystems, and narrowed down to the microscopic detail of genes. How do we provide explanatory order to this expansion of knowledge and complexity?

In a complex system of interacting and interdependent factors, how do we decide which factor has causal or explanatory priority, or controlling efficacy? How do we rank the different factors and determine the strength and direction of relationships and dependencies? Which factor is a cause, and which a consequence?

As the focus of research shifts from one factor to another, so too does the explanatory emphasis. The ranking of explanatory categories changes in the light of new evidence and our human need to prioritize.

The Modern Synthesis, as an explanation of evolution, was a product of the genetic revolution that occurred between about 1918 and 1942 during an analytic-reductive turn in thinking that was gathering momentum at this time as scientists and logicians looked for the foundations of the world in its smallest discrete constituents.

Dissatisfaction with the main tenets of the Modern Synthesis began to appear from the 1950s (e.g. organicist Waddington) to 1980s (e.g. evolutionary biologist Gould). These ideas were given expression around 2009[64] and summarized in a 2010 book by Massimo Pigliucci and Gerd B. Müller, Evolution: The Extended Synthesis whose themes have persisted as the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES).

Dissatisfaction with the Modern Synthesis derived from both theoretical objections and the findings of new research concerned with, among other factors, fitness landscapes, multilevel selection, epigenetic inheritance, cultural evolution, organismal development, developmental plasticity, niche construction, evolvability, phenotypic plasticity, reticulate evolution, horizontal gene transfer, symbiogenesis, and more. A recent synthesis of the EES can be viewed here.

In sum, the EES is an expression of disillusionment with the gene-centered analysis of evolution. It is a movement seeking a revision in the emphasis given to the various factors influencing evolution – those underplayed including organisms, agency, ecology, and the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

The revisionist proposals of the EES fall into two broad camps: those concerned with a modification of our understanding of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and those concerned with biological agency.

The most comprehensive current discussion of the philosophy and principles of agency in biology is Denis Walsh’s Organisms, Agency, and Evolution (2015). Walsh is a member of a team of four biologists concerned with agency in living systems whose objective is – ‘To develop a scientific theory of organisms as purposive agents and determine the explanatory concepts and structure of an agent theory in relation to conventional scientific object theories‘.

Walsh outlines his philosophical position as follows:

The ‘Aristotelian purge’ was seen as a pivotal achievement of early modern science. As a consequence of the scientific revolution, the natural sciences learned to live without teleology. Current evolutionary biology, I contend, demonstrates that quite the opposite lesson needs now to be learned. The understanding of how evolution can be adaptive requires us to incorporate teleology – issuing from the goal-directed, adaptive plasticity of organisms – as a legitimate scientific form of explanation. The natural sciences must, once again, learn to live with teleology.[53]

. . . the capacity of a system to pursue goals, to respond to the conditions of its environment and its internal constitution in ways that promote the attainment, and maintenance of its goals states[56]

Walsh points out that the purposive activities of organisms have a strong influence on evolutionary outcomes – that evolution is, in this sense, a by-product of organisms’ pursuit of their intrinsic purposes. Evolution is not a product of four discrete and independent processes – inheritance, development, innovations, and biased change. Rather, each of the component processes of evolution—like adaptive evolution itself— is a consequence of what organisms as agents do.

A new biological paradigm

If biology has ignored agency for centuries, if not millennia, then why do we need it now – and how are researchers to adopt it as a relevant, practical, and operational concept?

Science must study agency because it is a critical component of the real fabric of the natural world – it cannot be ignored simply because it was once treated as a philosophically misguided idea. If, indeed, ‘evolution is a by-product of organisms’ pursuit of their intrinsic purposes’ then our historical determination to exorcise purpose and agency from biology must be regarded as a major scientific and philosophical error of judgment.

There was a time when it was considered inappropriate to call humans animals – the meaning of ‘animal’ did not extend comfortably to humans. As biology progressed and the continuity of life was better understood, the word ‘animal’ took on a broader sense with humans accepted as a limited case. In this way, science has shifted our semantics. The same applies to the idea of organisms expressing purpose and agency. As biology has progressed ‘biological purpose’ and ‘biological agency’ have embraced a broader sense, with human agency (as conscious intention) a limited case of biological agency.

Being part of the real fabric of nature, agency has not been ignored by biological science, it has been hidden. The task is to convert the implicit into the explicit – to realize that the technical language of natural selection, adaptation, and fitness maximization tells the truth, but not the whole truth, it is a form of obfuscation and circumlocution – a cryptic terminology that obscures the reality of agency and purpose. It is OK to speak of the purposes of biological entities and what adaptations are ‘for’. This will, by convention, be resisted, and it will be claimed that it is a semantic error – but it will bring humans closer to nature by countering the detached mechanics of physics and chemistry. Being grounded in sound science, it will gradually become accepted.

The concept of agency in biology is gathering support. In a comprehensive philosophical coverage of ‘Agents and Goals in Evolution‘ (2020) with in-depth consideration of agential thinking and the agential idiom in biology, philosopher Samir Okasha cautiously concludes:

‘To the extent that an evolved organism is well adapted to its environment, and thus equipped with phenotypic traits that enhance its survival and reproduction, it can be validly treated as agent-like as long as a certain empirical precondition is met, at least approximately [the unity of purpose condition]

The reintroduction of agency and teleology to biology requires clarification, consensus, and an understanding of historical problems.

Seeking clarity on the notion of agency in biology Okasha (2023) offers a framework for dialogue that recognizes two roles or motivations for the word ‘agency’: first, as a thesis of agential individuation, that ‘organisms are agents’ (OAT) and, second, as a tool to aid the understanding of evolved biological behavior, the ‘organisms as agents’ heuristic (OAH). He proposes four non-vernacular senses of ‘agency’ and examines their suitability for application in biology: the minimal concept (doing something or behaving), the intelligent agent (having the capacity to adapt: as applied in AI), the rational agent (maximized utility: as applied in economics), and the intentional agent (use of psychological states—beliefs, desires, and intentions: as often applied in philosophy).

Our anthropocentrism drives us to investigate the agency and purpose so obvious in nature through the lens of human agency. So, for example, we ask, ‘Why do we treat organisms as if they experienced cognitive states when clearly they do not?’ Or, ‘Why, do organisms demonstrate behavior that is so similar to human reasoning?‘

This website is concerned primarily with the concept of organisms as agents (OAT). While human agency and metaphor can be useful tools in the study of biological agency this website takes the view that it is more scientifically informative to investigate human subjectivity through the reality of biological agency, than to understand biological agency through metaphorical idioms and lens of human subjectivity – though both approaches can inform.

Much can be learned by looking at human agency through the lens of biological agency – by acknowledging that human agency is an evolutionary elaboration, or limited case, of real biological agency – rather than biological agency being a creation of human minds that must therefore be psychologized.

This is a more empirical approach that prompts scientifically pertinent questions such as, ‘How do we account for the obvious similarity between, on the one hand, the non-cognitive goal-directed behavior found in all organisms and, on the other hand, the uniquely human cognitive faculty of intension?’ or ‘When cognitive metaphor is so patently unscientific, why do we persist in using it?

When we dismiss purpose and agency altogether by treating them as metaphor or heuristic (e.g. the plant wants water) we are mistakenly focusing on the metaphor rather than the agency. Plants have no cognitive faculties, but that does not mean they have no agency (see metaphor fallacy listed above).

Themes investigated on this website include the emphasis on organisms as being real agents, independent of any heuristic considerations relating to non-biological agencies; a close investigation of the relationship between human agency and biological agency and how this, in turn, relates to the minded and mindless in biology (including the actual evolutionary relationship between goal-directedness and cognition).

The analysis of agency in biology has the potential for major scientific contributions to our understanding of the origins and nature of human subjectivity. The benefits of agential studies in biology can flow into many disciplines, including developmental biology, bioengineering, biomedicine, microbiology, robotics, AI, and evolutionary biology.

Agency

What exactly do we mean by ‘agency’ and what are the most effective ways to investigate its relevance to biology? If biological agency is real, then what is its role in evolution?

This overview of agency begins with our general understanding of the notion of agency before looking at agency in nature, the characteristics of human agency, and the relationship between human agency and biological agency. It then focuses on the application of the concept within biological science.

‘Agency’ is a loosely defined idea with application in many disciplines, so it has a broad semantic compass. Dictionaries tell us that an agent is something that acts, so an agent could, for example, be interpreted in an extremely abstract, and general sense as a cause that brings about an effect. However, we are more likely to think of agency in the familiar and narrowly defined sense of the intentional behavior we associate with human activity.

Agency expresses at least a degree of autonomy and self-determination directed toward specific goals or objectives. An agent initiates or influences events, so its actions cause changes that are not entirely controlled by external factors. We can, however, imagine computer programs such as those of AI that display a non-living kind of agency that is independent of or, at least, superimposed on their human input.

The goals, or objectives of cognitive agents are uncontroversially referred to as ‘purposes’. We speak about the purposes (goals) of inanimate objects like chairs, knives, and guided missiles, but we do so mostly because they infer the human intentions involved in their creation; we do not regard them as independent agents.

Natural agency

Though rarely regarded as a crucial philosophical concept, the notion of agency sits at the center of our religious and scientific understanding of the world. What is it that generates activity in the universe, that initiates change, that has causal efficacy? Change can imply a mysterious, possibly supernatural, force of some kind – and forces are difficult to explain because they cannot be seen, smelled, heard, or touched.

More specifically, what is it that animates living things – that gives them ‘life’? What exactly is the ‘vitality’ that so obviously leaves a body when it dies?

Nature, in a broad sense, is full of powerful and terrifying non-biological forces (agencies): earthquakes, tsunamis, storms of thunder and lightning, fiery conflagrations, floods, plagues, famines, and disease. Why do these dreadful catastrophes happen, and why must humans suffer their consequences – and who or what is the agency behind them? It is hardly surprising that in such instances we personify nature with events controlled by punishing and rewarding human-like Gods.

The history of science can be understood as a progressive exorcism of agential spooks. It has always struggled with the intangibility of natural forces, even those of foundational physics. Some forces, for example, have an immaterial and mysterious capacity to act at a distance – which is especially spooky. Newton accounted for the effects of gravitation while refusing to speculate on what it was, and only relatively recently have we come to grips with the strange invisible attractive phenomena associated with electro-magnetism, while finding new puzzles like quantum entanglement.

When we confront the goal-directedness of organisms (biological agency) and their vitality, it too seems to imply some ineffable power – a kind of life force . . . living willpower, motivation, or animating principle. We think we are being detached and scientific when we describe this property in neutral language by saying that life has a disposition or propensity to act in a goal-directed way. But this hardly does justice to the real-time agential immediacy of life that seems much more than a mere propensity.

Such musings are ignored today. The various ‘pushes’ and ‘pulls’ of our lives – the needs, wants, desires, and aspirations that direct our behavior – seem neither mysterious nor unscientific.

While organisms survive, reproduce, flourish, and therefore persist, there is no logical necessity for this. We do not have to breed, or feed, or continue living – but something like a ‘will-to-life’ provides the driving energy, power, or force that keeps most of us going, most of the time.

This applies to all life, and especially mindless life. Very rarely do organisms terminate their lives under-essentially. If we humans suddenly decide to stop our life-affirming activities, then this is considered unnatural: we need professional help.

The ‘will to live’ is an integral part of our inherited biological nature; it no longer needs supernatural explanation. Why should discussing goal-directedness (the agency) of organisms imply the unreal, unscientific, or supernatural?

Minded humans evolved out of mindless organisms. Minded human life-affirming agency evolved out of the mindless life-affirming agency of mindless organisms. Human agency evolved out of biological agency.

Human agency

While human agency is strongly associated with rational considerations and deliberate intention, it is not expressed exclusively through the medium of conscious mental representations.

Human bodies demonstrate biological goals in several additional ways that include: the mindless but integrated and goal-directed biological processes of self-maintenance that include growth, metabolism, homeostasis, homeorhesis, and more. Then there are the minded but unconscious goals associated with our instincts and intuitions including our inherited objective, universal, and ultimate biological propensity to survive, reproduce, and flourish.

Like all organisms, we are engaged in a constant process of adjustment (adaptation) to what is going on both inside and outside our bodies, most notably those conditions that are important for our existence as determined by our human biology. It is these conditions that determine our commonsense reality or umwelt (see manifest image).

Key adaptive ingredients of the human cognitive agential umwelt include:

Intentionality – our goal-directedness as the purposive focus of our mental activity which we describe using the agential language of intentional psychology.

Conscious self-awareness of our actions and their consequences, so we can reflect on our thoughts, choices, actions, and motivation. This includes an awareness of our capacity for independent (autonomous) decisions that engage rational deliberation.

Capacity for self-regulation based on both individual and collective societal principles, values, norms and ethical precepts.

Creativity and the ability to learn from experience and acquire new skills in adjusting to our environments

Providing a concise summary of our human mental life is a tall order, but when well-founded, succinct statements – like principles and laws – have great explanatory power. From at least the time of the ancient Greek philosophers, our mental life has been subsumed under three useful categories: knowledge (epistemology), values (ethics), and reason (logic). These three drivers of human behavior will be re-visited at the end of this article.

Human & biological agency

This website argues at length (see articles listed at head) for the claim that human agency is best understood biologically as a specialized, highly evolved, and minded form of biological agency.

While the idea of evolution suggests transformation, it can also be usefully characterized as adding on to, or supplementing, what is already present. This is how Darwin understood biological evolution – as a process of gradual modification from common ancestors.

The necessity for all life to survive and reproduce, if it is to persist, is an ultimate goal that can be understood as an underlying theme for the vast graduated array of related organisms (with their supporting structures, processes, and behaviors) that make up the community of life.

All organisms, including humans, are subordinate to these ultimate goals of biological agency. However, because humans express their agency in a highly evolved cognitive form these underlying ultimate causes of behavior are concealed in proximate cognitive forms. So, for example, ultimately we eat to survive, but proximately we eat for the biological rewards of smell and taste stimulation, and the satisfaction of hunger. Biologically we have sex for the (ultimate) purpose of reproduction, but our human (proximate) incentive is the pleasure of physical closeness and orgasm . . . and so on.

These examples provide a window into the way that apparently unique human mental faculties are grounded in more general biology. It points to the way that our cutting off of mental faculties from other organisms can be a form of anthropocentrism, of human arrogance. While, after nearly 200 years of Darwinism, we now willingly accept the biological antecedents of our bodily structures we cannot accept that there are aspects or properties of our mental lives that are also shared with the community of life. Human minded agency is just one manifestation of ultimate biological agency and the biological condition of constant adjustment.

More precisely, the features that uniquely define human agency evolved out of the universal, objective, and ultimate characteristics that are common to all biological agents . . . the reason why we intuitively acknowledge plants and animals as fellow agents in a way that rocks are not. This is also the reason why human minded concepts share some characteristics (likenesses) with the mindless concepts we associate with mindless organisms – why there is a set of real properties connecting non-human organisms to human cognitive states.

There are scientifically grounded and real (not fanciful or metaphorical) reasons why we recognize likenesses between the behavior of non-human organisms and, for example, human purpose, agency, reason, value, knowledge, and more.

For those claiming no real connection between biological and human agency, there is the species-specific descriptive language of human intentional psychology. But while dogs and oak trees also express goal-directed behavior (agency) in their own objective and unique way, they do not have corresponding descriptive vocabularies. What words are we to use when trying to describe this real non-cognitive form of agency? Since the reality of objective non-human biological agency cannot be denied, but cannot be described by using the language of human cognitive psychology, what are we to do?

Since it is impractical to devise agential language for each species, but we wish to convey the reality of non-human biological agency, we resort to the use of human cognitive terms. These are then open to accusations relating to cognitive metaphor, heuristics, and so on. That is, real biological agency is described using unreal figurative terms (see metaphor fallacy above). These matters are discussed in the articles human-talk, being-like-minded, and biological values.

Suffice it to say here that we usually use the language of intentional psychology to draw attention to real and universal (shared) biological agency, not to literally imply that non-human organisms have cognitive faculties. We say a plant ‘wants’ water because we know it will die without it, not because we really believe that plants have cognitive faculties.

Conceptual analysis

The rough-and-ready semantic analysis of ‘agency’ given above tells us what we mean by agency in general. But how are we to narrow down these generalities to address the specific question of agency in biology?

One approach might be to first establish a range of different meanings of ‘agency’ and then see how these are applied by practicing biologists. This might help narrow down the field of possibilities when considering a definition.

Philosopher Samir Okasha (2018, pp. 12-15) has investigated four popular senses of ‘agency’ and investigated their appropriateness for application in biology: the minimal concept sense (doing something or behaving), the intelligent agent sense (the capacity to adapt: as used in AI), the rational agent sense (maximized utility: popular in economics), and the intentional agent (use of psychological states—beliefs, desires, and intentions: as used in philosophy).

Okasha himself recognizes the goal-directed behavior of organisms as an empirical fact.[40] However, while this website regards goal-directed behavior as sufficient to warrant the designation ‘agency’, Okasha embarks on a more rigorous investigation by examining agency through minded concepts of agency, like intelligence, reason, and intention (see above).

This approach proceeds from the popular mainstream assumption that agency is a minded phenomenon. This is, as it were, a ‘top-down’ approach, attempting to understand organisms in general by looking through the lens of human cognitive agency.

This seems unnecessarily conceptually complex when a ‘bottom-up’ methodology could yield valuable empirical insights. But, how could that possibly be done?

This website regards agency as a general biological or organismic phenomenon, not a strictly human characteristic (see, for example, Being like-minded). Human (minded) agency is treated as a highly evolved and limited case of biological agency.

From this perspective, intelligence, reason, and intention are minded cases of biological agency. That is, there is an evolutionary connection between biological agency in general and uniquely minded human agency in particular. It then becomes a productive scientific endeavor to examine the evolution of cognitive agency through an empirical investigation of the graded evolutionary diversity of organisms (including the properties and relations of their structures, processes, and behaviors) as they exist across the community of life. This begins with a determination of features that are shared by both human and biological agency, not those that are unique to humans: it is a study focused on biological agency, not human cognition.

This ‘bottom-up’ approach treats agency as an empirical investigation of real agential characteristics, while a ‘top-down’ approach interprets biological agency through the cognitive filter of human agency with its mind-like heuristics and cognitive metaphors.

In short, we understand the relationship between human agency and biological agency in a more scientifically productive way when viewing human subjectivity through the lens of real biological agency, rather than trying to understand biological agency through the metaphorical lens of human subjectivity (though both approaches may yield insights).

In a recent paper philosopher Okasha (2023) asks, ‘What is distinctive about living organisms compared to entities at other hierarchical levels?’ concluding that agency is a ‘candidate for the job’ because organisms exhibit agent-like attributes such as ‘ . . . making choices, learning about the environment, and performing actions, that other biological entities do not’. Apart from his unabashed use of cognitive metaphor, he recognizes two roles or motivations for the word ‘agency’: first, as a thesis of agential individuation, that ‘organisms are agents’ (OAT) and, second, as a tool to aid the understanding of evolved biological behavior, the ‘organisms as agents’ heuristic (OAH).

As indicated before, it is the OAT, that is addressed on this website, with the OAH treated as an empirical, rather then conceptual, challenge.

Biological agency

When asked to name a biological agent we intuitively think of an organism. However, the entry in Wikipedia for ‘biological agent’ describes it as an organism or toxin ‘that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism or biological warfare‘ (28 April 2023). There is nothing in that article addressing the matters that are discussed on this website.

Biology has, until recently (when cells and genes have enjoyed a period of ascendency), found little difficulty in allocating organisms a central place in biology. But there is a problem with the word ‘agency’. For many reasons (see articles at the head of this page) notions of biological agency and purpose are currently considered unorthodox biology. For centuries the topic of agency in biology has been swept under the carpet – denied or ignored – it is the elephant in the biological classroom.

Critically, agency is considered by many people as exclusively associated with human cognition.

However, all organisms are goal-directed autonomous biological agents that act on and respond to their conditions of existence. While agency is usually associated with human cognitive traits like intention and deliberation, the presence of agency in non-cognitive organisms confirms the existence of non-cognitive agential traits – a characteristic of non-cognitive organisms that is referred to here as pre-cognition.

Thinking about the agency of organisms forces us to consider their goals or purposes and the characteristics that establish biological objects as discrete individuals or biological categories. Is biological agency a fiction, or is it a critical feature that distinguishes life from non-life? And if all organisms display some form of agency, then what is the difference between this agency and the agency we associate with human intentions? Does it make sense to speak about cognitive and non-cognitive agency? And, if it does, could there be an evolutionary connection between the two? It draws our attention to the possibility of an evolutionary connection between the agential behavior of mindless organisms and the intentional behavior of humans but, more importantly, it forces us to reconsider the relative significance and relationship between the key factors of evolutionary theory.

Brainstorming the notion of biological agency gathers ideas that include: purposeful behavior, self-regulation and homeostasis, response to stimuli, adaptation and evolution, reproduction, energy processing, organizational complexity, information processing, autonomy and independence, and the capacity for learning and adaptation. How can this complexity be condensed into something more simple?

The view of biological agency presented here is grounded in the general notion of an intentional agent (the organism) performing purposeful actions driven by goals or intentions (the ultimate and mindless goals of survival and reproduction). This theoretical stance can be exemplified in graded physical forms as, say, the minimal agent with the basic capacity for self-regulation and responsiveness, the intelligent agent with cognitive abilities beyond mere responsiveness, and the rational agent capable of decision-making based on reasoning.

Organisms influence their own persistence, maintenance, and function by regulating their structures and activities in response to their conditions of existence. They are not passive elements of environments, they actively engage with them: they not only shape their own evolutionary paths, they contribute to their broader ecological context. That is, they establish the conditions of their own evolution. They regulate their internal environment (homeostasis) and respond to their environmental conditions with physiological adjustments and, over generations, evolutionary adaptations.

The dynamic interplay between organisms and their environmental pressures and conditions determines their evolutionary trajectories as traits that confer advantages in particular environments are passed to future generations by the feedback process of natural selection. In co-evolutionary terms, each species’ traits and behaviors influence the evolution of other organisms thus helping to shape evolutionary pathways.

These are the questions that will be addressed as this article systematically investigates what is meant by a biological agent, biological goals, and the means used by biological agents to pursue their goals.

Pre-cognition & cognition

Organisms are goal-directed biological agents that act on, and respond to, their conditions of existence. However, we strongly associate all agency with human agency and human cognition, and this means that if we are to accept the agency of non-cognitive organisms then we must also accept that they have non-cognitive agential traits. This is the currently unsettling world of ‘mindless’ biological purpose and biological agency.

This website describes the realm of non-cognitive agential traits as pre-cognition and explores the possibility that the properties of cognition evolved out of universally shared properties of ancestral pre-cognitive traits.

The biological agent

We intuitively treat organisms as the basic operational unit of biological science – the canonical biological agents. Indeed, biology is sometimes defined as the study of organisms.[99]

The primacy of organisms has, however, been challenged on several fronts as more biologists have accepted that agency is distributed generally through living systems.

This has happened in response to several questions. Why are we to privilege any of the hierarchical levels of biological organization above any other since each level seems to have its own agency, role in evolutionary selection, capacity to adapt, and so on? How are we to distinguish life from non-life? All organisms, we now know, are composed of cells so aren’t cells the foundational units of biology? Or, since genes seem to be crucial component of biological continuity, encoding all the necessary conditions for life, then maybe it is genes that are pulling the strings of life? The seeming independence of many organisms may be challenged by their dependence on populations of associated viruses and bacteria such as the surface and gut organisms that are crucial to the lives of humans to become multi-organisms sometimes called holobionts. Included here are aberrent ‘individuals’ such as clonal forests of trees, the Great Barrier Reef, Portuguese Men ‘o War, and others. It is also evident that organisms as collectives – populations, colonies, swarms etc. – display their own integrated unity such that individual organisms may be subsumed under greater wholes.

Exceptions and gradations have therefore challenged simple notions of a single biological agent, basic biological unit, or of organisms as being exceptional.

This complexity has resulted in an existential pluralism in which the choice of biologically privileged unit and its autonomy becomes a matter of context and convenience, depending on the question being posed. Indeed, biological subdisciplines – genetics, cytology, physiology, ecology etc. – have their own pragmatically determined and preferred biological units.

The remaining part of this section on biological agents considers an unconventional taxonomy of biological objects (useful when addressing other biological questions), before examining the conventional division of biology into hierarchical levels of organization and its challenges to the primacy of the organism.

Biological objects

We like to think that the categories we use to carve up the biological world correspond to the way the world actually is – to reality. It is clear, however, that these categories are, to some degree at least, categories of convenience that arose as a historical legacy. We are, of course, at liberty to divide up the world as we please, and one useful distinction may be drawn between structures, processes, and behaviors (click this hyperlink for a justification of this taxonomy). The utility of this classification is that it embraces the full range of biological phenomena and biological subdisciplines while opening the mind to biological possibilities.

Structures – (both wholes and parts) are the physical ‘things’ of biology that ranging from sub-organismal entities like molecules, genes, cells, tissues, and organs, to supra-organismal entities like colonies, populations, and ecosystems – even mother nature, or planet Earth (Gaia).

Processes – imply the notions of time and change that are obscured in the language of structure. Biological processes occur both inside and outside but in exchange with living systems as open systems. In organisms they include photosynthesis, homeostasis, blood circulation, growth, metabolism and so on.

Behaviors, both minded and mindless in both organisms and their parts, are treated as being goal-directed, at least in the minimal sense of having functions.

This classification loosely reflects the history of biology as it moves from the static description of things (morphology, taxonomy) to their dynamic processes and functions (physiology) to their behaviors (ecology, ethology, psychology). It also reflects a scale of somewhat increasing agency.

The biological hierarchy

The conventional way of investigating biological phenomena is to give serious consideration to the objects of biology’s hierarchical levels of organization.

Biology is traditionally organized into interactive hierarchical levels of organization as levels of increasing physical complexity – from molecules to genes, cells, tissues, organs, organisms, communities, populations, ecosystems, biomes, and biosphere with each level loosely corresponding to a field of study. Each level can then be allocated an individual identity, not only in terms of its organization but also its agency, role in evolutionary selection, and so on.

How are we to distribute agency among this possible range of biological objects?

If organisms are understood as the canonical biological individuals and agents then the agency we might attribute to other biological objects (structures, processes, behaviors) plays a subordinate role to the overarching agency and individuality of the organism.

What is the justification for this claim?

If we take an egalitarian approach to the biological significance of objects of graduated organizational complexity then this leads to an agential pluralism with agency all the way down.

The organism then becomes a reference point for the categorization of biological objects which extend into the sub- and super-organismal realms.

Autonomy

The human discrimination of objects in the world depends, at least in part, on our human mode of perception and cognition.

How do we justify the individuation of biological objects?[65]

All objects of the universe are connected in space and time, so no object is autonomous in an absolute sense.

The structural and functional independence of every biological object is clearly a matter of degree. A living heart can only exist outside a body when specially preserved. For scientific convenience, we individuate categories appropriate for study – like organisms, bones, leaves, cells, populations, and ecosystems. Though distinguished as ‘individuals’ they differ widely in their degree of autonomy within the world.