Norfolk Island Pine

Characteristic silhouette of Norfolk Island Pine

Araucaria heterophylla

as seen in Australian coastal townships, parks and gardens

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Introduction – Norfolk Island Pine

Norfolk Island Pine, Araucaria heterophylla, is an Australian signature tree. Challenging our human time-scale its botanical family dates back about 200 million years to a time when today’s northern and southern hemispheres were part of the single supercontinent Pangaea. On the human time-scale it has strong Aboriginal connections through its close relative the Bunya-Bunya Pine, A. bidwillii, a tree whose cones, maturing every 3-4 years, united Aboriginal tribes over a wide region in song, dance, story-telling and trade as they feasted on its nuts. It played a key role in the drama of maritime scientific exploration, imperial economic botany, and an unprecedented plant obsession that gripped Europe’s social and intellectual elite, being a major factor in the decision to establish a British settlement in New South Wales. Description of the various species entailed some of the key botanical and political personalities of the day in both Britain and the new colony.

Today, the striking architectural form of this tree has guaranteed it a place in ornamental culture in warmer climates and as an indoor pot plant in temperate regions. Its characteristic silhouette is seen not only on the flag of its native island but in coastal avenues around Australia and elsewhere, notably New Zealand, Hawaii, S California, Canary Iss, Cuba, Florida, Fiji, and Micronesia, in the parks and gardens of Buenos Aires and warmer climate coastal areas of Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Chile, South Africa and coastal United States. This familiar tree, which grows naturally only on an isolated island in the Pacific over 1,000 km from mainland Australia and hundreds of kilometres from its nearest neighbours New Caledonia and New Zealand, was one of many that made up the thriving plant exchange that was taking place between Britain and its colonies at the time of Australian settlement – it is a kind of subtropical Neo-European[1] icon.

First European sighting

James Cook stumbled into Norfolk Island on his second voyage of scientific discovery in the Pacific in HMS Resolution, the remarkable columnar pines (Araucaria columnaris, previously named A. cookii and now known as Cook’s Pine) that grew on the just-visited New Caledonia were still fresh in his mind and he recognised that the pines he now saw were different species.

It was the afternoon of 10th June 1774 when Cook strode ashore at Duncombe Bay on the north-west coast of Norfolk Island at a site where a Monument to his landing now stands. With the ship needing repairs Cook was anxious to move on to New Zealand and so only one afternoon was spent ashore before they sailed on. Cook’s journal noted that, after lunch:

‘my self, some of the officers and gentlemen went to take a view of the Island and its produce … We found the Island uninhabited … the chief produce of the isle is Spruce Pines which grow here in abundance and to a vast size, from two to three feet diameter and upwards, it is of a different sort to those in New Caledonia and also to those in New Zealand and for Masts, Yards &ca superior to both. We cut down one of the Smallest trees we could find and Cut a length of the upper end to make a Topgt Mast or Yard … Here then is another Isle where Masts for the largest Ships may be had.’

The trees were the Norfolk Island Pine, Araucaria heterophylla and, as on previous occasions when he had encountered new land he “took possession of this Isle as I had done of all the others we had discovered, and named it Norfolk Isle, in honour of that noble family.“

Cook had set sail from England in 1772 and did not know that the Duchess would not be able to acknowledge his gesture as she had just died in the previous year. The short time was sufficient for the three botanists to make some collections, including samples of the flax for the Royal Navy, and for Cook to summarise their visit in his journal:

‘We observed many trees and plants in common with New Zealand; and, in particular, the flax plant, which is rather more luxuriant here than in any part of that country; but the chief produce is a sort of spruce pine, which grows in great abundance, and to a large size, many trees being as thick, breast high, as two men could fathom, and exceedingly straight and tall. This pine is a sort between that which grows in New Zealand, and that in New Caledonia; the foliage differing something from both; and the wood not so heavy as the former, nor so light and close grained as the latter. It is a good deal like the Quebec pine'[Pinus strobus]

Six years earlier Cook had achieved fame for his first circumnavigation of the world on which he explored the east coast of New Holland with the wealthy naturalist Joseph Banks and his assistant Johann Solander, a former student of the famous Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. Together Banks and Solander had for a fortnight revelled in the botanical treasures of a site Cook would later name Botany Bay to commemorate their botanical zeal. Banks had been invited as naturalist on the second voyage but when he was told that his suggested plans for plant storage aboard ship were impractical he petulantly stamped his foot on the dock and refused the offer. Even so he had generously suggested two competent Prussian botanists, Johann Forster and his son Georg for the trip and once under sail they had also picked up Johann Sparrmann at the Cape, another student of the great Linnaeus. It was these botanists who made and named the first plant collections on Norfolk Island. Cook’s and other journals of crew members record the visit noting the Norfolk Island Pine, Johann Forster reporting that they collected cabbages [the soft growing tips of palm trees] and other ’greens’ and what he called the Cypress-Tree ‘. . . got a fine Yard for a Top-gallant-sail. . . ’ Astronomer William Wales noted the ‘… soil to be exceedingly rich and deep’. Samples of the flax were returned to England.

Cook’s landing place on the north-west coast at Duncombe Bay when ‘discovering’ Norfolk Island on 10 October 1774

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Politics of Australian settlement

Norfolk Island Pine was a factor closely linked to the settlement of Australia. Based on his experience with Cook’s first voyage Joseph Banks had recommended to a select Parliamentary committee that Botany Bay was ideally situated for settlement. Following Cook’s visit to Norfolk Island on his second voyage there were calls to link Norfolk Island to the new settlement. Royal Society member of Parliament and former chief engineer of the British East India Company John Call proposed to the Home Office in 1784 that:

‘This Island has an Advantage not common to New Caledonia, New Holland and New Zealand by not being inhabited, so that no Injury can be done by possessing it to the rest of Mankind … there seems to be nothing wanting but Inhabitants and Cultivation to make it a delicious Residence. The Climate, Soil, and Sea provide everything that can be expected from them. The Timber, Shrubs, Vegetables and Fish already found there need no Embellishment to pronounce them excellent samples; but the most invaluable of all is the Flax-plant, which grows more luxuriant than in New Zealand.’

One of Cook’s botanists, George Forster, now professor of natural history at the University of Vilnius in Polish Lithuania, in 1786 published a paper “Neuholland, und die brittische Colonie in Botany Bay” pointing out the advantages of Norfolk Island such as “the nearness of New Zealand; the excellent flax plant (Phormium ) that grows so abundantly there; its incomparable shipbuilding timber”.

The idea of Australian settlement was now strongly linked not only with convict settlement but also the strategic and economic potential of pines and flax on New Zealand and Norfolk Islands. Arguments for the use of these straight pines as masts for British Men-o-War and the plentiful supplies of a flax that could serve the same functions as cotton, hemp and linen had become persuasive: supplies were within a fortnight’s sailing from Botany Bay. With the presence of warlike Maoris on New Zealand in 1786 the British Government conceded that Norfolk Island should be a supplementary settlement. There were other strategic concerns. France was now taking an interest in the Pacific. In August 1785 Jean-Francois de Lapérouse had set out from Brest in command of the ships Boussole and Astrolabe ostensibly on an expedition of scientific discovery but perhaps there were other intentions. Accordingly the instructions delivered to commander of the First Fleet, Arthur Phillip in April 1787, as he set out for Botany Bay included orders to also settle Norfolk Island “as soon as Circumstances may admit of it … to prevent its being occupied by the Subjects of any other European Power”. As it turned out the Lapérouse expedition had intended to settle New Zealand before the British and to investigate Norfolk Island and British activity in the region, his ships anchoring off the north of the island on 13 January 1788 but with heavy seas he did not attempt a landing.

Georgian buildings at the Second Convict settlement site in Kingston

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Norfolk Island settlement

Settlement of Norfolk Island is divided into four periods: Polynesian occupation (c. 1,000 to 1,400 CE); First Convict Settlement (1788-1814); Second Convict Settlement of Kingston (1825-1855); Pitcairn Islander (1856). Pitcairners arrived on 8 June 1856 (celebrated on the island as ‘Bounty Day’) as 194 descendants of the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian wives; they had been struggling with overpopulation on Pitcairn Island and, with Queen Victoria’s approval, were transported across the Pacific to occupy the old military site at Kingston.

Soon after the arrival of the First Fleet at Port Jackson Governor Phillip sent a party of 15 convicts and 7 free men in HMS Supply commanded by Henry Lidgbird Ball and with Philip Gidley King to be the Superintendant of the newly occupied Norfolk Island, to clear the land, plant crops and vegetables, and prepare for the commercial exploitation of its flax. It appears that although Governor Arthur Phillip’s instructions to Philip Gidley King had only referred to the flax, others on HMS Supply like midshipmen Fowell and Waterhouse were under the distinct impression it was the Norfolk Island Pine that was of greatest concern.

Though settlement of Norfolk Island was clearly intended to deter French colonial ambitions Norfolk Island Pine (Araucaria heterophylla) and Flax (Phormium tenax) weremajor items on the agenda. The party arrived at the island on 29 February, less than two months after the arrival of the First Fleet in Botany Bay on 18 January, but with no harbour or safe landing place they were not ashore until 8 March. The transition was smooth except for the disturbing absence of a safe landing spot and harbour. With the food situation in Sydney becoming increasingly desperate the numbers of convicts and marines sent to Norfolk Island steadily increased and the early anticipation that the island could supply Port Jackson with produce was thwarted as crops did not perform and the lack of a harbour hindered communication. In 1790 there was a major set-back when HMS Sirius, commanded by Captain Hunter, was wrecked on the reef but without loss of life.

In spite of these difficult times many convicts chose to remain as settlers when their sentences expired: with an adequate food supply and away from military discipline the environment would have been much better than in England. By 1792 the population had grown to over 1000. Over time the convicts became more difficult to control and, with Sydney at last finding its feet and, in spite of some resistance, everyone on the island was recalled to Sydney in 1814. The Second Settlement was a period of extreme misery as up to 4,000 convicts were subjected to military imprisonment and discipline at Kingston from 1825 to 1855, a period when massive clearing of the vegetation on the island took place.

St Barnabas Church

Roof beams constructed of Norfolk Island Pine

Focal point of the Church of England Melanesian Mission College 1880-1920

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Finally in 1856 the island was occupied by Pitcairn Islanders, the offspring of mutineers on Bligh’s expedition to take bread-fruit from the Pacific to the Caribbean in HMS Bounty. Bligh, renowned as a bully, had been evicted from the Bounty by mutineer Fletcher Christian. Leading a crew of 18 men in a 23 foot open dingy with few supplies Bligh navigated for 3,500 nautical miles over seven gruelling weeks to eventually reach Timor. Meanwhile the mutineers had split up, some returning to Tahiti while others had followed Fletcher Christian to settle on tiny Pitcairn Island. Those mutineers who went to Tahiti were captured by HMS Pandora and shipped back to England in irons housed in a cell called ‘Pandora’s Box’ from which they were finally released when the Pandora hit a reef in Australia. Surviving prisoners were returned to England where four were identified by Bligh as being innocent and spared, three were hung, two were found guilty but pardoned, and the remaining man was reprieved by a technicality. Though mutineers on Pitcairn Island escaped Bligh’s vengeance, the Tahitian men who accompanied them were used as labour and eventually killed Fletcher Christian and the other white men who had monopolized the stolen Tahitian women and land.

Kingston – Norfolk Island – 2011

Here Philip Gidley King and the first settlers put ashore on 8 March 1788

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Economic botany

After 100 years of war, much of it fought on the high seas, Britain had stripped its native forests of the timber so desperately needed for shipbuilding. Imports now came from Nova Scotia, North America (esp. New England), the Scandinavian Baltic, and Russia. But poor relations with America, which was to culminate in the American War of Independence (1775–1783), threatened the American supplies. Almost all the hemp and flax used by the Royal Navy was imported from Russia via the ports at St Petersburg (Kronstadt) and Riga but in the summer of 1786 the Empress Catherine of Russia had asked her merchants to restrict Baltic supplies of flax (Linum usitatissimum ), used in the navy to make sails, and hemp (Cannabis sativa) which was woven into ropes and cordage.

In a letter to Prime Minister Pitt dated 5 Sept. 1786 Comptroller of the Navy Sir Charles Middleton wrote:

‘It is for Hemp only we are dependent on Russia. Masts can be procured from Nova Scotia, and Iron in plenty from the Ores of this Country; but as it is impracticable to carry on a Naval War without Hemp, it is materially necessary to promote the growth of it in this Country and Ireland‘.

So it was that one month after the decision to settle Botany Bay Norfolk Island became associated with the settlement plans for New South Wales. Plans for a double colonization were printed in The Universal Daily Register (today’s The Times ) on 23 Dec. 1786 which reported:

‘The ships for Botany Bay are not to leave all the convicts there; some of them are to be taken to Norfolk Island, which is about eight hundred miles East of Botany Bay . . . ‘

About 15 years before, Cook’s eyes had seen on the shores of New Caledonia and Norfolk Island vast forests of ship’s masts and spars ideal for the British Man-o-War. He was also aware of ‘flax’ plants used by the Maoris of New Zealand that could be used as a source of fibre and was delighted to see the same plants growing on Norfolk Island where they could be harvested without threat from the fierce Maoris he knew would meet him in New Zealand. Though the commercial and strategic potential of these two plants seemed assured they were both to prove impractical as the 1788 convict settlement on Norfolk Island was to demonstrate. The wood, though useful for construction, was inflexible, brittle, and knotted where the whorls of branches fed into the trunk: it was totally unsuitable for masts. The flax was pursued for several years, two Maori men even being kidnapped in the hope that they would pass on the skills of preparing and weaving the fibres (as it turned out they could not help as this was ’womens’ work’ that they knew nothing about). After much testing the Secretary for the Colony of New South Wales finally in 1789 acknowledged that the much-hoped-for ships masts would not eventuate:

‘. . . unfit for large masts or yards, being shaky or rotten at thirty or forty feet from the butt; the wood was so brittle that it would not make a good oar, and so porous that the water soaked through the planks of a boat which had been built of it.

Norfolk Island Pine (Araucaria heterophylla) and Flax (Phormium tenax), Cook’s landing site, Duncombe Bay

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Evolution of Araucarias

Plants in the botanical family Araucariaceae[17] date back over 200 million years to the Late Jurassic geological period. The cone-bearing plants pre-dated the flowering plants by many million years, the first flowering plants appearing about 125 million years ago. Araucaria heterophylla is a conifer related to the northern hemisphere pines and cypresses: its genus, Araucaria (19 species) being one of only three in the botanical family Araucariaceae, the other two being Agathis (21 species,found in Australia but especially well known through the giant kauris of New Zealand), and secondly the genus Wollemia (1 species) the famous Wollemi Pine, Wollemia nobilis, (only recently discovered in the Wollemi National Park in 1994.[8]

The genus Araucaria, once dispersed across both hemispheres, now occurs naturally in Australia, New Caledonia (about 700 km due north of Norfolk Island), South America, and Norfolk Island. The Norfolk Ridge split off from Gondwana about 65 million years ago, the only remnant of the Ridge that is now above sea level being New Caledonia where there is a concentration of 13 species of Araucaria. However, these species grow on rock that is relatively young, only 40-13 million years old so its origin may be more distant.

Molecular analysis, which give an indication of evolutionary relationships between species, suggests that in the group of species related to Norfolk Island Pine, Queensland’s Hoop Pine-like ancestors (A. cunninghamii) evolved first, ancestors of the Norfolk Island Pine then splitting off before the cluster of species that are found on New Caledonia. As the volcanic Norfolk Island is only2.2-2.5 million years old the origin of its single endemic species remains unclear especially as the highest points along the Norfolk Ridge are considerably lower than the lowest known sea depth, seeming to eliminate the idea of dispersal from ancient land masses no longer in existence.[7] No living Araucaria suggests itself as an ancestor of the Norfolk Island Pine.

Norfolk Island Pine – Araucaria heterophylla

Female cones in the upper canopy

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Accessed 7 August 2017

Botanical name

The genus name Araucaria. was established by Antoine Laurent de Jussieu who was a botanist at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. He was famous for his ‘natural’ system of plant classification that he maintained in competition with the ‘artificial’ system of Linnaeus.

The word Araucaria is derived from Araucanos the name given by Spanish conquistadors, who appropriated it from the Incas, to the ‘Indians’ of Chico Sur in Central Chile, a people now called the Mapuche. In their former lands the first-named species (Araucaria araucana) grows naturally. [McInnes-King, p. 30] Although Norfolk Island Pine was well known to Cook and the early settlers on Norfolk Island, it was not until 1807 that it was given a formal scientific description by the Forsters, father and son, as Araucaria excelsa (?Eutassia excelsa – most outstanding). Their description was based on a specimen collected by Philip Gidley King, the first Superintendent on the island from Araucaria heterophylla (synonym A. excelsa: excelsa – tall or lofty) . As its vernacular name Norfolk Island Pine implies, the tree is to , a small island in the between , and . The scientific name heterophylla (“different leaves”) derives from the variation in the leaves between young and adult plants. The genus, once dispersed across both hemispheres, now occurs naturally in Australia, New Caledonia (about 700 km due north of Norfolk Island), South America, and Norfolk Island. The Norfolk Ridge split off from Gondwana about 65 million years ago, the only remnant of the Ridge that is now above sea level being New Caledonia where there is a concentration of 13 species of Araucaria. However, these species grow on rock that is relatively young, only 40-13 million years old so its origin may be more distant.

Molecular analysis, which give an indication of evolutionary relationships between species, suggests that in the group of species related to Norfolk Island Pine, Queensland’s Hoop Pine-like ancestors (A. cunninghamii) evolved first, ancestors of the Norfolk Island Pine then splitting off before the cluster of species that are found on New Caledonia. As the volcanic Norfolk Island is only2.2-2.5 million years old the origin of its single endemic species remains unclear especially as the highest points along the Norfolk Ridge are considerably lower than the lowest known sea depth, seeming to eliminate the idea of dispersal from ancient land masses no longer in existence. No living Araucaria suggests itself as an ancestor of the Norfolk Island Pine.

Common name

Norfolk Island Pine is not a ‘pine’ in the strict botanical sense, that is, it is not a member of the genus Pinus which we know through the needle-like leaves and ‘pine cones’ on trees like the plantation or Radiata Pine, Pinus radiata: the genus Pinus does not occur naturally in Australia. The common name was probably intended in the broad sense of ‘conifer’ or cone-bearing tree. Australia’s other two species in this genus are also called ‘pine’, the Hoop Pine, Araucaria columnaris and the Bunya Bunya Pine, the Aboriginal name for Araucaria bidwillii, of south-east Queensland whose nuts were the reason for Aboriginal corroborees and feasting every three years or so when the trees produced their crops of cones bigger than pineapples containing nuts the size of European chestnuts (and tasting similar when roasted). Other common names for this particular species include: Star Pine, Triangle Tree and Living Christmas Tree as, for the first few years of its life it maintains a rigidly symmetrical growth form with whorls of branches distributed up the trunk, the lateral branches in each whorl becoming progressively shorter towards the growth tip.

General description

Norfolk Island Pine trees take 60-80 years to mature, most growing to about 40 m tall but exceptional specimens reaching 60 m or so. Mature trees can maintain their shape in the face of incessant strong and salty winds which makes them ideal for coastal planting in suitable climates while young trees show an extraordinarily symmetrical branching pattern and foliage distribution, a feature that has made them popular house plants in cooler climates. By age 40 years the branching has become much more diffuse. Trunks are straight with branches spreading in whorls of eight or so from nodes along the trunk.

On Norfolk Island they may be festooned with the lichen Usnea. Leaves are awl-shaped, incurved and about 1-1.5 cm long varying somewhat according to the age of the tree and their position in the canopy, the thickest scale-like leaves being on the coning branches are in the upper crown. Female cones generally appear on trees older than 15 years while the male tassel-like cones may take as long as 40 years. Female cones are compressed globose and about 10-12 cm wide, taking about 18 months to mature. Heavy coning occurs every three to five years, the cones disintegrating so that, in general, only the individual winged and spined seeds are found on the ground: they are a major part of the diet of the endangered endemic Norfolk Island Green Parrot (Cyanoramphus cookii) found only in the Norfolk Island National Park and surrounds. Lifespan of the tree seems to extend under suitable conditions towards 200 years. The first Araucaria planted in Portugal is still growing at the Parque do Monteiro-Mor (the Jardim Palmella) in Lumiar. It was planted in 1841/2 and is now about 171 years old and 60 m tall. The tree had been brought from an English nursery by Friedrich Welwitsch who worked for the Duque de Palmela, Pedro de Sousa Holstein.[13] The tallest tree on The Gymnosperm Database[11]The tallest known tree is at Tedeschi Winery, Ulupalakua, Maui, Hawaii. It is 136 cm dbh and 51.8 m tall. The Australian Flora treatment describes its height as ‘Tree to 70 m tall with trunk to 2 m diam.’ But trees currently growing on the island do not approach these dimensions.

For a full botanical description of the family Araucariaceae, genus Araucaria and species Araucaria heterophylla see Flora of Australia vol. 49: 543 (this is volume 1 describing the flora of Australia’s oceanic islands and it covers the floras of Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island), see also the Atlas of World Conifers web site of Aljos Farjon,[12] and The Gymnosperm Database[11]

Timber

Though not suitable for masts the wood was still workable and immediately put to use on the island as on 19 March 1798, within a fortnight of settlement, a saw pit was constructed for converting the trunks into planks and in October a consignment was sent to Port Jackson, probably the island’s first export.[2] A small but sturdy sloop, the Norfolk, was build with convict labour using planks of Norfolk Island pine for its construction. As a highly useful seaworthy ship this was immediately confiscated by the mainland settlement at Sydney on the pretext that on the island it could provide a means of escape and would incite the island convicts to mutiny. This vessel was to make the first historic 1798 circumnavigation of Tasmania by Matthew Flinders and George Bass proving the existence of Bass Strait but in 1800. Ironically it was wrecked by convicts who seized it in an escape attempt from Sydney.

Norfolk Island Pine trunk section photographed in the Commissariat Museum at Kingston, Norfolk Island and showing the whorled branching pattern at a node

Courtesy Kingston Museum

Image: Roger Spencer, May 2011

Used as a structural material on the island it was also found handy for roof shingles although tanked rainwater became unpalatable as a result. In the late 1950s a trial shipment of Norfolk Pine logs was sent to Sydney plywood manufacturers in the hope of developing a timber export industry for the Island. Although the plywood companies reported excellent results the industry was deemed not by the Norfolk Island Advisory Council who decided to reserve local timber production for use on the Island. The timber is good for and is used extensively by Hawaiian craftspeople and for the production of island souvenirs.[19]

Use in horticulture

The distinctive appearance of this tree, with its widely spaced branches and symmetrical, triangular outline, has made it a popular cultivated species, either as a single tree or in avenues, its salt-tolerance and capacity to grow in deep sand making it ideal for coastal areas. When the tree reaches maturity, the shape may become less symmetrical. Despite the endemic implication of the species name Norfolk Island Pine, it is distributed extensively across coastal areas of the world in Mediterranean and Humid Subtropical climate regions due to its exotic, pleasing appearance and fairly broad climatic adaptability. Norfolk Island Pines are planted abundantly as ornamental trees throughout coastal areas of Australia, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Chile, South Africa and coastal United States where it is grown outside in warmer coastal towns of Southern California, Florida (large numbers are produced in S Florida for the pot plant industry) and the NW coast of Mexico. Similarity of young foliage has led to some confusion with A. columnaris as has occurred in Hawaii.[9] Many of the “Norfolk Island pines” growing in Hawaii, including their descendants growing as potted ornamentals on the U.S. mainland, are actually , the two species having been confused when introduced.

Juvenile foliage, the form widely used in North America for Christmas trees

Image: Roger Spencer, May 2011

Though introduced to Britain by Joseph Banks in 1793 but cultivation requires a near frost-free climate. However, it was occasionally seen growing in warmer climate gardens in Cornwall and in the Tresco Abbey gardens on the Scilly Isles.[6] In America and Hawaii especially it is prized as a Christmas tree that can be grown indoors all year with especially attractive juvenile foliage, the authoritative American horticultural tome of the early 20th century, Bailey’s Standard Cyclopaedia of Horticulture, stating in 1939 that ‘Araucarias are probably the most prized pot evergreen in cultivation’, adding that it is the Norfolk Island Pine that is the most popular.[3] An overview, by Alistair Watt, of the Australia horticultural use of araucarias, and especially the Norfolk Island Pine, is given in Bieleski & Wilcox: it outlines Mueller‘s distribution of specimens to William Hooker at Kew in 1859, and A. columnaris to the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens in 1864. A list of outstanding cultivated specimens in South-eastern Australia is given in Spencer (1995).

First cultivation in Australia

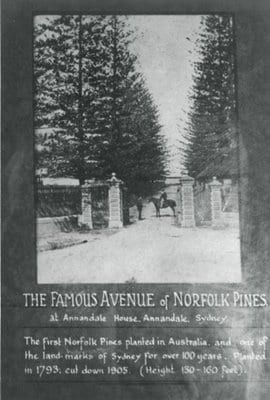

The first Norfolk Island Pines cultivated in Australia were planted at Annandale Farm, the property of George Johnston (1764-1823). Johnston was a military officer on Norfolk Island from March 1790 until February 1791. He received a the land grant at Petersham Hill (near Sydney) that was to become Annandale Farm in February 1793 and here he planted an avenue of trees from seed he had brought from Norfolk Island.[10]

Though the foundation date of the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney I disputed the generally-accepted date of 13 June 1816 is marked by the planting of an Araucaria heterophylla, known locally as the Wishing Tree which died and was removed in 1945.

The first trees cultivated in Australia, planted in 1793 and cut down in 1905

Courtesy Leichhardt History Collection

Cultivars

As the habit of the tree as well as the colour and form of foliage is variable, a number of dubious cultivars have been recognised as well as some with silvery-variegated foliage. The classic A Handbook of Coniferae and Ginkgoaceae of Dallimore and Jackson, first published in 1923 but revised and reprinted through to 1974, lists the cultivars ‘Albospica’, ‘Gracilis’, ‘Leopoldii’, ‘Muelleri’, ‘Silver Star’, and ‘Virgata’ and also notes that it had been widely planted in South Africa and other areas with a subtropical climate including the Mediterranean, Azores and as a pot plant in other European countries. The current International Register of conifer cultivars lists 18 cultivar names of which 11 are currently accepted although probably no more than 3-4 are currently in cultivation.

On Norfolk Island

At the time of settlement evergreen subtropical forest covered the island. Tree ferns and flowering trees reached a height of 10-20 m or so and these were overtopped some 20-30 m by the Norfolk Island pines especially on coastal headlands or in local groves. Accounts of early settlers and crew of vessels indicate that the tree was largely confined to the coastal areas with few found inland, an observation backed up by the illustrations of Ferdinand Bauer in the early 19th century. Many were huge specimens, Quaker botanist James Backhouse reported a fallen tree almost 60 m tall others with girths of 8.8 m measured 1.2 m up the butt, and another 37 feet 11 m up the butt.[15]

The IUCN Red Data List classifies the tree as vulnerable D2 in its natural habitat.[5] Today there has been a massive planting program of the tree with natural stands mostly within the Norfolk Island National Park in the north-west. There are active revegetation projects and programs for the control and removal invasive species. The natural vegetation of Phillip Island is slowly recovering following the elimination of goats and pigs in the 1920s and the more recent removal of rabbits. In suitable climates it is relatively easy to grow and has become naturalized on the foreshore to the lagoon on Lord Howe Island.

Norfolk Island Pine (Araucaria heterophylla) on Norfolk Island festooned with the lichen Usnea sp.

Image: Roger Spencer, May 2011

Related species

The modern botanical family Araucariaceae comprises three genera: Agathis (Kauris), Araucaria, and Wollemia (containing the single living species W. nobilis, discovered in 1994). The first plants in the fossil record that can be allocated to this family date to the Late Triassic about 210 million years ago in medium to high latitudes of the SW (Gondwanan) part of the supercontinent Laurasia. In the Jurassic to Middle Cretaceous about 200-100 million years ago as Laurasia was beginning to split up and Gondwanan land masses segregate the family spread to colonise virtually the whole world. From about 85-65 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous and Palaeogene. evolution of a diverse range of flowering plants and changing climate and geography concentrate the family to high latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere. Modern genera are now evident and species can be allocated to Wollemia, Agathis and four broad sections of Araucaria.

In the Neogene to Recent times from about 22 million years ago current distribution patterns emerged with last remnants in India and Western Australia becoming extinct and the family restricted to the Southern Hemisphere. Its Gondwanan relative from Peru, the Monkey Puzzle Tree, Araucaria araucana, is so named because its prickly leaves and surfaces baffle even the smartest monkey. We must assume that the prickly leaves of this tree like those of the Australian Bunya Bunya Pine, A. bidwillii, were an adaptation to dinosaur browsing. Strangely, though a tropical tree A. araucana will grow in chilly England where it was introduced in 1795 and in Ireland, where it is still a popular landscaping tree but it struggles in a climate like that in Melbourne. Araucaria bidwillii, A. cunninghamii, A. heterophylla and A. columnaris were all popular in Australian 19th and early 20th century parks and large gardens but their appeal now seems to be on the wane. The social history of the genus is told in a fascinating account by ‘Araucariaist’ David McInnes-King which includes the story of his personal pilgrimage to each species in its natural habitat (see General references).

The gemstone jet is a type of lignite and a precursor to coal described geologically as a mineraloid since it has an organic origin in fossilized wood. Famous jet deposits at Whitby, England, date to the early Jurassic (Toarcian) Age about 180 million years ago and derived from wood similar to that of Monkey Puzzle Tree, Araucaria araucana.

Monkey Puzzle, Chilean Pine – Araucaria araucana

A. araucana, the hardiest species in the genus, was discovered by Europeans c. 1780. It is the first-described species of Araucaria by Chilean botanist Juan Ignacio Molina (1740-1829) in 1782. It was introduced to England by Archibald Menzies, botanist on HMS Discovery in 1795 on the Vancouver voyage when he had pocketed some nuts offered as a dessert when the ships officers were entertained at a banquet given in their honour by the Governor of Chile. Menzies grew five aboard ship which, on return, he presented to Banks at Kew, one surviving until 1892. This species is described by William Bean (1863-1947) as ‘… the most remarkable hardy tree ever introduced to Britain’: it was most certainly a Victorian era favourite. Bean was one of Britain’s greatest tree specialists and a Curator at Kew where he served for 46 years.[4] Today it is the most important coniferous timber tree in Chile and the indigenous Mapuche people, who call the tree Pehuén, are dispossessed, their former lands now settled by Europeans, but they are a proud people still with a strong association to the tree whose pollen and nuts are sold in the local markets. Neuquen, the Argentinian province where it grows naturally, uses a stylised silhouette of the tree on its flag.[16]

Cook’s Pine – Araucaria columnaris

Araucaria columnaris, once named A. cookii in commemoration of the famous circumnavigator who first spied it on a small island off the coast of New Caledonia, present-day Isle of Pines, writing:

‘On one of the western small isles was an elevation’ like a tower; and over a low neck of land, within the isle, were seen many other elevations resembling the masts of a fleet of ships”. Later he observed that ” … they had much the appearance of tall pines, which occasioned my giving that name to the island” and again ” I was, however, determined not to leave the coast till I knew what trees these were which had been the subject of our speculation, especially as they appeared to be of a sort useful to shipping, and had not been seen anywhere but in the southern part of this land” And then after landing and making an inspection “We found the tall trees to be a kind of Spruce Pine, very proper for spars, of which we were in want. We were now no longer at a loss to know of what trees the natives made their canoes. On this little isle were some which measured twenty inches diameter, and between sixty and seventy feet in length, and would have done well for a foremast to the Resolution had one been wanting …” “The wood is white, close-grained, tough, and light’

Johann Forster named the tree Cupressus columnaris in 1786 and mistakenly assumed it to be the same species as the Norfolk Island Pine. A specimen was collected, preserved in Banks’s Herbarium, and figured in Mr. Lambert’s splendid work, under an impression that the species was identical with that of Norfolk Island, and on the same plate with the perfect cone of the latter species.[20] The first plants grown in England had been sent to the Royal Horticultural Society from Van Diemen’s Land, the result of collections made by Captain Erskine and Charles Moore, the Director of the Sydney Botanic garden when the pair visited New Caledonia and some of its adjacent islands in HMS Havanna. It was introduced to Hawaii from Sydney Botanic Gardens in 1851 (along with A. bidwillii and possibly A. heterophylla) and here some 8,600 grow in forest reserves.[9]

Trees exhibit a noted phototropic or geotropic effect, those in Australia tending to lean consistently to the north while those in California lean to the south, the angle of inclination increasing with greater distance from the equator.[21]

Bunya-Bunya Pine – Araucaria bidwillii

Found in only two locations, the largest just north of Brisbane from the Bunya Mountains to the Blackall Range. Heavy coning every 3-4 years attracted Aborigines from a wide area to feast, enjoy song, dance and trade from January to March. Pineapple-like female cones can get close to the size of a football and are the heaviest of all conifers attaining more than 6 kg posing considerable danger to bystanders as they can fall whole. In 2014 arborists at the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne collected 126 cones from a single tree. Nuts can be eated roasted, boiled or raw and have the flavour of baked potato. In respect of this tradition Governor Gipps on 14 April 1842 denied occupancy licences in these areas but these were later revoked, the tree being logged until in 1908 the Bunya mountains National Park was created. John Bidwill collected in the Blackall Range in , returning to Kew with seed which was grown, the species described by Director William Hooker and named after its collector. Like the Norfolk Island Pine it has been distributed widely across the globe being more resistant to cold than the other species except Monkey Puzzle, the parks of Buenos Aires for example containing many trees.[14] Amazingly it seems possible that the closest known relative of this species is a fossil plant, A. sphaerocarpa, collected from the Thames basin in England.

Hoop Pine – Araucaria cunninghamii

Just as Cook’s Pine dominates New Caledonia, Norfolk Island Pine Norfolk Island, the Hoop pine is a landmark tree that dominates its surrounding vegetation its scattered distribution in Australia from northern New South Wales through Queensland extending into the New Guinea Highlands and western Irian Jaya. Joseph Banks’s botanical collector Allan Cunningham, who was to become Director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens, had collected specimens of this species while exploring Moreton Bay with Surveyor Oxley in 1824 its description in 1832 being attributed to Cunningham himself. Though logged for some time, in Queensland and New South Wales native stands are conserved on Crown land.

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

In his book Tyranny of Distance historian Geoffrey Blainey examines the consequences of Australia’s geographic separation from its cultural origin in Britain but also its Neo-European offspring including the United States. He also re-examines the motives for Australia’s initial colonisation concluding that with the scarcity of timber and materials for sails and ropes the decision to establish a convict settlement in New South Wales in 1788 was strongly influenced by the presence of potential ‘flax’ and ‘pine’ alternatives on Norfolk Island and New Zealand. The history of the Norfolk Island Pine takes us back in geological time to Pangaea, to the happy times of Aboriginal feasting, as a major reason for settlement in the colony of New South Wales, looming large in the early history of Australia as it occupied the minds of the British parliament and admiralty and becoming an important part of the lives of people like James Cook, Joseph Banks, Arthur Phillip, Philip Gidley King, Matthew Flinders, and George Bass.

The latest update of The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species released on July 2nd 2013 includes a global reassessment of conifers. According to the results, 34% of the world’s conifers are now threatened with extinction – an increase by 4% since the last complete assessment in 1998.[18]

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . substantive revision – 23 July 2020

Georgian buildings at the Second Convict settlement site in Kingston

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Cook’s Pine, Araucaria columnaris, formerly A. cookii

Cook spied these trees on the Isle des Pines, New Caledonia, and considered ideal for ships’ masts

Image – Roger Spencer – May 2011

Bunya-Bunya Pine, Araucaria bidwillii, from mainland Australia where it was the source of nuts harvested by Aborigines at 3-4 year intervals for feasting corroborees

Image: Roger Spencer, May 2011

0 Comments