Now

Mens’ 100 m London Olympics 2012

Usain Bolt clocks 9.63 seconds

How does physics give us a universal measure of time and how does our biology influence our perception of time?

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Darren Wilkinson – Accessed 8 Sept. 2015

Introduction – Now

What do we mean when we talk about ‘Now’?[1]

The article on the flow of time suggested that when we talk about the ‘flow’ of time, we are using the movement of spatial objects as a metaphor (we are spatializing time by speaking of it as if it were a physical object moving in space). The use of metaphor helps us overcome the abstract nature of time.

To remove some of the ambiguity that arises when we spatialize time we can use time words instead of space words. The word ‘lapse’ was suggested as a time word to express the feeling of ‘passage’ that we associate with time.

This article considers three key aspects of time lapse:

1. We think that time lapse occurs right now in the present, but what exactly do we mean by ‘now’ or the ‘present’: can we be more precise by giving ‘now’ an actual temporal duration? Perhaps physics and biology can help here?

2. Is it possible to estimate the degree to which the lapse of time in the present or ‘now’ is a subjective and specifically human perspective on time?

3. How can we account for the biological sensation we experience with time – the feeling of dynamic passage, flow, and passing?

What is ‘Now’?

Now, presentism, & history

A moment after the Big Bang the universe consisted of undifferentiated plasma that has subsequently differentiated into the matter of the galaxies we see today. Part of this process of cosmic evolution has been the evolution of life and human beings. Whatever we mean by ‘now’ or ‘the present’ we do not perceive the whole of time and space laid out before us, all at once. We assume that this process has taken place over a time interval. The Big Bang clearly does not exist now even though we may see evidence of its past occurrence within the universe.

We can create precise theoretical and mathematical models that explain things would have been like at the Big Bang. Physicists are able to calculate what the universe would have been like in the now three seconds after the Big Bang. To suggest, like the eternalist, that our belief in a current state of the universe is illusory, that all historical moments of the universe exist equally, is totally counter-intuitive. We sense that the present is real in a way that the past and future are not. The future is what is later than now, the past is what was earlier than now, and the present is what is simultaneous with now.

Clearly the inanimate world does not have the conscious memory and anticipation that surrounds the human perception of now, but the presence in geological strata of fossils of extinct animals are like a physical ‘memory’ or record of things past – they mark a once-existent ‘now’ of long ago. The eternalist, however, needs convincing evidence to demonstrate that when we infer a past ‘now’ from fossils and rock strata observed in the present, we are in fact deluding ourselves with subjective notions of past, present and future.

The duration of Now

The word ‘now’ like the word ‘time’ is riddled with polysemy so we cannot hope for precision here. However, for our purposes we can consider three major senses – physical, biological, and linguistic:

• The cosmic now – a near-durationless instant, the smallest possible lapse of time – sometimes called the punctiform present or punctal point – a notion derived from mathematics: the extremely brief objective moment defining the boundary between determinacy and indeterminacy (physics)

• The specious present – ‘now’ as we perceive it in daily life (biology)

• A contextual now – an interval of time relating to the linguistic context (linguistics)

The cosmic now (physics)

The cosmic now is the temporal equivalent of a spatial point in mathematics: it is a theoretically durationless point in time, like the theoretical mathematical point in space that has no length, height or breadth. There are sound mathematical reasons for such theoretical entities but time without duration is an incoherent objective concept.

The punctiform present is the shortest possible time interval over which change can occur, the knife-edge of temporal change in the universe. We do not know if time, like matter, is composed of meaningful physical units. Perhaps it is , or theoretically infinitely divisible. For the presentist, and our purposes, the cosmic now is an imperceptibly brief duration of time during which there is an objective change in the configuration of the universe. The cosmic now is the moment where the indeterminacy of the future gives way to the determinacy of the past, the emergence of determinate reality.

The punctiform present is not an advancing ‘now’ moving through time, it is more a measure of change: however, we sense it as dynamic and this aspect is discussed in (3).

Now and Relativity

We do not have a god’s-eye view of the universe outside of space and time from which we could see the universe in a particular configuration at a particular time. Instead we exist ‘within’ space and time and, like other objects, are subject to the effects of relativity. In speaking of relativity, and in giving examples of time dilation it is conventional to refer to ‘observers’ and the ‘observer’s frame of reference’. This has given the spurious impression that relativity is a function of the perceiving mind. After all, it is the ‘observer’ who sees the surprising consequences of relativity. In fact, the critical factors are the conditions that pertain at particular places and times: whether there are observers there or not is irrelevant. Frames of reference have nothing to do with the people that may or may not be in them as ‘observers’.

Light takes time to reach us. As you read these words you are doing so with light emitted a billionth of a second ago, the other side of the room about 10 billionth of a second, the moon 1.5 seconds, the sun 8 minutes. The presentist may be assumed to believe that what is happening now on Sirius is simultaneous with what is happening now on Earth. But if Sirius is 10 light years away – according to the frame of reference there may be 20 years difference in calculated simultaneity. Spatial locations moving relative to one-another will have a different perspective on what is happening now. By implication there is now absolute now. Owing to the restrictions imposed by the speed of light there are relativistic adjustments to be made on cross-cosmos comparisons of ‘now’ but each place in the universe has its now. By this view now or the present is part of the objective world and therefore not the product of our particular perspective.

The specious present (biology)

The experience and perception of time is discussed by Le Poidevin (2015).

We see colours, hear sounds, feel the effects of gravity, and are aware of temperature – all through our senses, but how is time perceived? Though we may think of time-perception in relation to change, the non-simultaneity or order of events, or the ideas of past, present and future – it is probably duration that is most obvious.

So how and where, then, do we sense duration?

If we imagine counting the ticks of a clock as a way of marking duration then our awareness of time lapse as something that is mind-independent (the ticking of a clock) is registered in our brain in the form of some kind of memory trace. It is as though the longer ago an event occurred the weaker is the trace, thus giving us a measure of duration. Successful estimation of time intervals is present across the animal kingdom.

In an interval of any duration there will be earlier and later parts, a past and a present. This suggests that the present, now, must be durationless. Considering the finite speed of both light and sound it appears that we can only ever perceive what has past but we are adapted to experience only the very recent past, except when we are star-gazing.

As soon as we become aware of the present it has become past. When we listen to a piece of music we seem to retain notes or phrases in our heads as a brief memory, so that within our subjective present we can enjoy the sensation of a combination of successive notes, not just each note as an individual and separate experience. If we are familiar with the music then within that present moment we may also eagerly anticipate a few notes to come. The same applies when we listen to a spoken sentence. In this way our subjective present may incorporate parts of both the past and future. There is no precise answer to questions about the length of our perceived present and that is presumably why it has become known as the ‘specious present’. In a loose and general sense we can regard the specious present as that brief period of time in which we react to objective external stimuli, say our response-time when driving or playing table tennis. Presumably the duration of the specious present relates to our short-term memory and assorted mental processing including brief memories and anticipations that take place before we become aware that some particular perceptions are being replaced by others.

Human and animal perception of time is a matter for empirical science. In the case of human beings it is studied as mental chronometry in experimental psychology. Mental chronometry records brain response times to various percepts under many conditions. If we take our response time when driving as an example of the specious present then it is about 1.5 seconds, and for a responding click on a smartphone it is about 0.3 seconds.

There are obvious psychological constraints to what we can encompass in our present. We do not see the rapid refreshing of a TV screen or the individual pictures that make up a celluloid movie although we know that they exist. This suggests a possible connection between our sense of duration and our vision.

Now as an evolved adaptation

Each animal species has a set of senses as evolved adaptations that are a consequence of that animal’s historic environments. Collectively these senses determine the perceived reality of that animal’s world. We can determine to some extent the range of the senses of animals, their sensitivity to smell and so on. Though we cannot experience what they experience we have some idea of the nature of their sensory world. Clearly the experienced reality of a herring is

different from that of a bird or human being. We also know that the perceived reality of humans, unaided by technology, is not privileged over other species: birds see better than us, dogs have a more highly developed sense of smell and hearing, whales hear better underwater and so on. One feature of our senses is that they sample only part of what it is possible to sense. Humans hear and see within a limited range of what it is possible to hear and see, since we use only those waves of sound and light that aided our survival in the past. In a similar way we are biologically attuned to the range of time durations that were of adaptive value to us in the past. A cloud of bats flying inside a cave, in order to avoid collision, must be much more finely tuned to short time intervals than us. It seems reasonable to suppose that time-sense will be roughly related to factors like body size and energy expenditure.Many organisms respond far more rapidly than us to changes in their environment. There is little doubt that the length of our human specious present is a biological adaptation that allowed us to respond effectively to stimuli and threats in our historic environment. The specious present (largely unconscious) will also be different for different animals since many animals respond to time lapses are imperceptible to us.

Our interest is in the implications of the specious present for the philosophy of time. We can conclude from the above that the period of time we generally refer to as ‘now’ is not the perception of a universal now but a biological temporal adaptation unique to the human species and loosely indicated by our reaction times; it is our human perceptual time-reality. Our human specious present will be of different duration to that of other animals and it is not privileged over theirs, it is simply a consequence of our own particular evolutionary history – just as the colours we see and sounds we hear are different from those of other animals. We accept the limitations of out spatial perception, acknowledging that many animals perceive space in different ways from us, discriminating shorter or longer distances, but we find this difficult to accept for time which we feel must be the same for all creatures.

The brain as a temporal sense-organ

Time is not generally included as one of our senses, perhaps this is a shortcoming. There seems no reason why our human sense of time should be considered any different from our other five senses of touch, taste, sight, hearing, and smell. Unlike other senses time-sense does nothave a dedicated sense organ: maybe it is an integration of the other senses as a brain process. Another difficulty is that our five of touch, hearing, sight, sound and smell all responding to physical stimuli: smell molecules, light waves, sound waves and so on. What physical object are we sensing when we sense time? How do we perceive time?

The dynamic quality of time

Perhaps we do not sense time itself but other things? Now seems to be constantly changing as new experiences are perceived and processed in our brains. If our brain is acting like a sense organ then we sense not only a fixed term present or now that lasts about 0.3-1.5 seconds but also a now that is constantly changing and hence our sense of ‘lapse’. How can this be explained? If the lapse (flow) of time is a subjective matter then it requires psychological explanation? There is no shortage of possibilities:

• The lapse of time from future, to present, to past with its associated changing facts and truth-values has the feeling of movement

• Spatialized language of time (watches ‘running fast’, time ‘passing by’ etc.) implying the movement, spatial extension and contraction, varying temporal intervals expressed like distances or lengths, even the temporal accretion of facts and events – all suggest movement

• The arrow of time with its language of directional movement ‘forwards’ and the impossibility of time going ‘backwards’ suggests spatial movement in a direction

• Our perception of change, succession, and continuity are all reminiscent of spatial movement

• Physical objects and events seem to pass into, through, and out of existence, and for anything to change it must become older

• The incessant processing of information in the brain also suggests continuity

The specious present: past, present, future

We might say that the future is anticipation and the past is remembrance. Philosopher of time Adrian Bardon from Wake Forest University describes it as psychological projection that is indispensable for us to maintain a coherent reprsentation of the world. He notes Kant‘s observation that mental recollection of its nature must entail past and present, that we have an innate sense of temporal succession, and that space and time are necessary mental constructs constraining our spatial and temporal perception to ‘here’ and ‘now’, adaptive ideas without which we could not survive: we must impose order on the world whether it objectively exists or not.

Perhaps we can understand the temporal perspectival subjectivity of past, present, and future by using the spatial perspectival analogy of my computer being ‘here’ and your computer being ‘there’ while for you this situation is reversed.

Contextual present (language)

A further sense of the present or now relates more to linguistic usage than a cosmic or perceived now. In everyday language we employ a highly variable, in fact unlimited, period corresponding to now or the present. With this usage the interval referred to as present depends on the context. For example, if we wish to draw attention to any particular duration that includes now, then we refer to that as the present. So, if we are timing a race we might speak of the present second, if we are on a long plane flight we might refer to the present hour, when giving a history lesson encompassing many thousands of years we might even talk about ‘this year’ as a present or current year, even the ‘present millenium’, and so on.

So, we can divide the present into smaller and smaller temporal intervals or units of duration. Yes, we do seem to have a ‘reaction time’ that correlates well with what we tend to call ‘now’. But no matter what interval of time we call ‘present’ (say an almost immeasurable instant, a reaction time of 0.3-2 seconds, a minute, or hour) we find ourselves relating to things that occurred before and after others. Augustine of Hippo pointed out that we cannot measure time if: it has no duration, or if it is not yet in existence, or if it has passed. And yet we do measure time. Augustine believed that time only exists as memory, sensation and anticipation and it is these that we measure when we measure time. He too was an idealist.

Both the specious present and contextual present indicate perspectival aspects of the present. However, it is argued here that, as with human perception in general, though we have a distinctly human perspective on time this does not necessarily mean that time or the world do not exist or that our perception is illusory, we are simply sampling a limited part of the whole in our own particular human way.

Key points

Any coherent philosophy of time must be clear about what is meant by ‘now’.

Two major usages of the word ‘now’ have been isolated, one used in the world of mathematics and physics, the other in the world of common linguistic usage and biology. For the purposes of physics ‘now’ is the smallest duration of time in which change can occur and be represented mathematically. This ‘now’ of physics can be represented as a punctiform point in the space-time grid of the block universe in which all points are treated as existing equally.

The ‘now’ of everyday experience and common usage, although sometimes used contextually to refer to almost any duration, mostly refers to an ill-defined duration (the specious present) roughly corresponding to the human reaction-time, a period of around half to one second.

We know that durations in the universe can extend from the smallest possible duration of physics to the full duration of the universe.

We must assume that our biological awareness of time is restricted to the range of duration that has proved the most evolutionarily important for our survival as biological organisms. Most important here has been our reaction time (different from that of many other organisms). Just as our hearing covers only a limited range of sound waves (those that have been historically adaptive) so we are biologically tuned to those durations of time that have been historically adaptive, that have allowed us in the past to respond in a ‘timely’ way. We do not have an inner sense of a millennium (although we can imagine some extremely long-living organism that might have such a sense) because millennia are not part of our experienced world. And we must assume that the tiny durations recorded by some animals (like the radar-response time of bats in a cave) and which are imperceptible to us, have been of inconsequential adaptive value to ourselves.

So we need to distinguish between the ‘now’ (or ‘present’) of physics which is the smallest knife-edge duration in the universe and the everyday ‘now’ of biology which is a uniquely human perspective on time.

Philosophically it is important to note that because humans have a perspective on time this does not mean that ‘now’, the present, is itself illusory. Our senses interpret a vibrating column of air as sound and a light wave as a particular colour. Sound and colour are our biological way of perceiving sound and light waves and this is undoubtedly perceived differently in different animals. Though our perception of light and sound is our perspective, our perceived reality, that does not mean that the waves themselves are illusory, they do exist objectively in the universe and it may even be said that we experience them ‘directly’. However, we must recognize that the ‘way’ we experience them is our species-specific human biological ‘interpretation’ of them.

In summary, our experiential or specious ‘now’ is a biological adaptation, a duration or reaction time of roughly 0.3-2 seconds that has been of historical evolutionary significance. The cosmic now is the smallest unit of time that can register change (the boundary between determinacy and indeterminacy). Even so, in our pursuit of time it is the cosmic now, T(*), that we must follow. Biological now, T(now) is our biological evolutionary response to T(*), it is the way we feel time.

It is true that T(now) is subject-dependent and that we are projecting times onto the world (projectivism), and also true that we are perceiving time from an anthropocentric human perspective (perspectivalism). But it is a mistake to assume that projectivism and perspectivalism have no objective counterpart – the counterpart is change in the world outside our minds, in the external world, as T(*), the universal boundary between determinacy and indeterminacy.

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . 22 July 2023 – minor edit

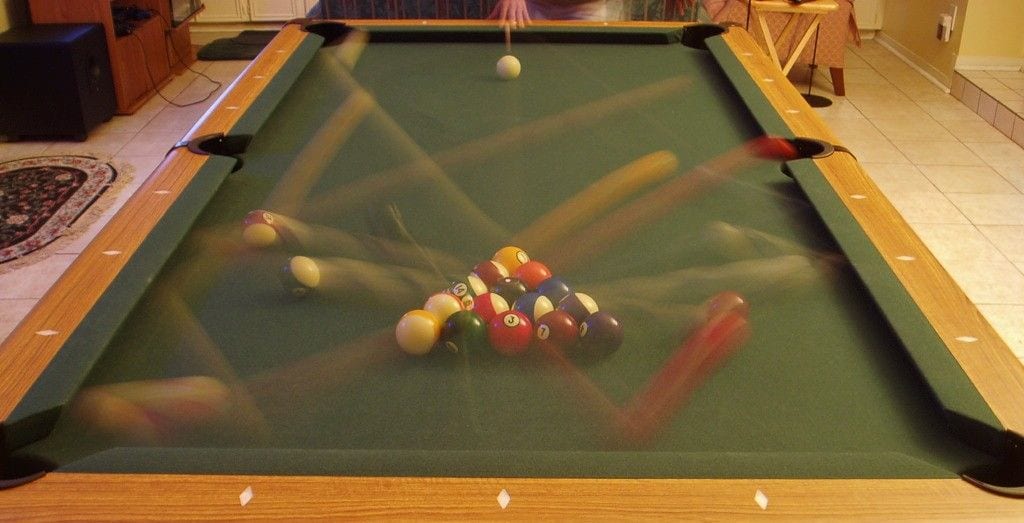

Time-lapse photograph of an 8-ball break

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons