Australian gardening literature

The Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens

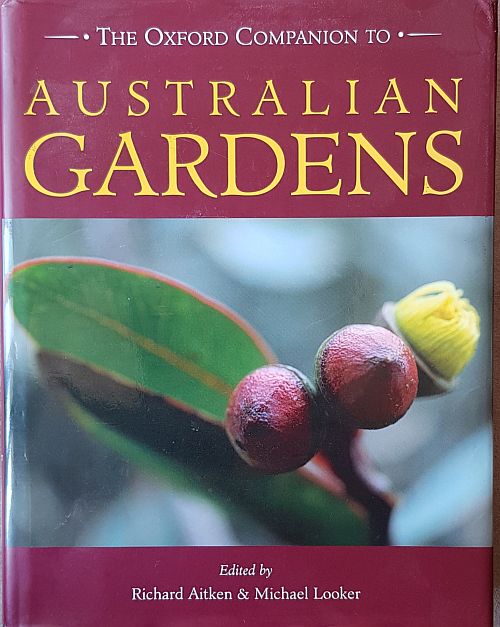

Published in 2002 and edited by Richard Aitken and Michael Looker this is foundational Australian gardening literature

Image Roger Spencer

This article is about the history of Australian garden literature. For a selection of contemporary books see here. And for a more general historical account of English-speaking gardening literature see horticultural literature.

Introduction – Australian Gardening Literature

Gardening literature – its books, journals, magazines, newspaper articles, nursery catalogues, and web apps – is the touchstone of the gardening world; it leads fashion by heralding new techniques and ideas while at the same time providing steady support for existing traditions. Because gardens and their contents are so short-lived (along with horticultural fads and fashions) horticultural literature also serves as the written archaeology of the garden historian.

In spite of the strong association of wives and women with gardening (in 1899 Burnley Horticultural College had 72 women students and 13 men)[21] there are, until recent times, sadly, few female authors.

Histories

Part of the tradition of garden literature has been the synoptic accounts of Australian garden history itself, or major parts thereof, including Beatrice Bligh’s Cherish the Earth: The Story of Gardening in Australia (1973), Howard Tanner’s The Great Gardens of Australia (1976), Peter Cuffley’s Cottage Gardens in Australia and the encyclopaedic Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens (2002) compiled by Richard Aitken and Michael Looker and the many essays appearing in the journal of the Australian Garden History Society after its formation in 1980.

Bibliographies and historical lists of plants

The most comprehensive account of horticultural literature in Australia is that of Victor Crittenden (1986). Apart from general commentary Spencer and Cohn (1986) have produced a brief list of horticultural literature that would have been fairly widely available in the nineteenth century. Both horticultural and botanical literature of the 19th century is discussed by Cohn (1995). For an account of the nursery catalogues of South-East Australia, a valuable archive of changing plant fashions, there is Rosemary Polya (1981), and for plants listed in Victorian and Tasmanian Nursery catalogues from 1855 to 1889 Brookes and Barley (2009). There is a special book collection devoted to landscape architecture held at the Canberra College of Advanced Education donated to the library by Richard Clough and catalogued by Victor Crittenden (1986). This collection is separate from the main collection and has been added to by various people.

It is characteristic of horticultural literature that much of it is ephemeral, uses its own publishers, and is therefore often lost or difficult to find.

The following account is based largely on Victor Crittenden’s book A History and Bibliography of Australian Gardening Books 1806-1950 which covers the topic in much more detail with a supplementary bibliography in which each book is cited in full with a note on its contents. I have followed his historical periods here.

1788-1806 – Survival

With self-sufficiency as a first priority the settlers of the First Fleet assistance would have been eager to take advantage of any agricultural and horticultural expertise and to scour books and printed information that had been brought on the ships for anything that might help the situation. Though Governor Phillip had a little farming experience in his reports back to England he grumbled about the lack of gardening experience within his community. Some books were known to have come out with the fleet but with survival at stake it would be some time before ornamental gardening could begin.

Horticultural literature in Australia begins with books brought out from Britain which we must assume had some influence on early approaches to agriculture and horticulture. Among the First Fleet agricultural books were Arthur Young’s Annals of Agriculture (begun in 1784 and eventually extending to 45 volumes) held by Lieutenant Johnstone and Jethro Tull’s Horse Hoeing Husbandry taken by Philip Gidley King to Norfolk Island.[1]

Without doubt the most prolific end trenchant horticultural chronicler of the early nineteenth century was J.C. Loudon. His publications covered in astonishing detail the horticultural matters of the day. His output and depth will never be paralleled. He established his oevre with the successful An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1822) followed up by The Encyclopedia of Agriculture (1825), as a link between he horticultural community as a whole there was the Gardener’s Magazine (1826, first truly horticultural magazine in the UK) followed by the Magazine of Natural History (1828). His predilection for massive compendia continued with The Encyclopedia of Plants (1828), Hortus Britannicus (1830), The Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, Villa Architecture (1834), Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838), Suburban Gardener (1838), The Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs (1842) and On the Laying Out, Planting and managing of Cemeteries (1843). Both John and Jane Loudons’ many and extensive works were not only the leading literature in Britain but well known and readily available in the British colonies, especially Australia where, for example, the first edition (1813) of An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture carried imprints of Howe (Sydney) and Melville (Hobart Town) alongside the familiar name of Longman.[3] An Encyclopaedia of Agriculture (1825) probably encouraged the use of plantations and arboreta and the Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1824) was a source of all manner of gardening information. It was in the more modest gardening style of the suburban villa garden that the influence of the Loudons was greatest.

John Loudon promoted, in his Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion (1838) the Gardenesque style which was recommended for the newly peopled, and thinly inhabited, countries, such as the back settlements of America and Australia.[4] Sydney’s Rookwood Necropolis was established as a garden cemetery based on examples in America and Britain, and likely influenced by Loudon’s On the Laying Out, Planting, and Managing of Cemeteries, and on the Improvement of Churchyards (1843)[5] and Moore was responsible for the layout of many parks and gardens including Centennial Park following Loudon principles. In Victoria Ferguson made several references to the Gardenesque style of Loudon which prevailed in Australia, albeit less precise, throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.[6]

There is little doubt that the educated Australian gardeners would have accessed at least some of these works, notably the Suburban Gardener.

The Early Colonial Period dating from 1806 to 1850 is characterised by the practical survival of the convicts and early settlers before a subsequent period of civic expansion.

1806-1830 – Casual literature & first books

An old printing press had been brought out with the First Fleet but it was not until 1806 that the first gardening literature appeared gardening notes, almanacs and advertising matter. George Howe the Government Printer produced the New South Wales Pocket Almanac … (1806) part of which was the influential Observations on Gardening (pp. 13-25, published separately by Mulini Press in 1980) which included an annual garden calendar along with practical advice on vegetable gardening and fruit tree budding. This was later followed in the same tradition by the Hobart publication Van Diemen’s Land Pocket Almanac … (1824).

From the early days collections of exotic plants were accumulated by the colony’s wealthier men, notably William Macarthur and Alexander Macleay, their excess stock being distributed through nurseryman Thomas Shepherd. Scotsman Thomas Shepherd was formerly a nurseryman and landscape gardener from Hackney in London. After trying his luck in New Zealand from March to June 1826 he then moved to New South Wales where he set up the Darling Nursery named after the Governor. As a contemporary of Humphrey Repton he followed the principles of landscaped parkland rather than the urban villa gardens that were espoused by John Loudon in England and which soon gained favour in the colonies.

Lists of seed and plants appeared in the newspapers an example of the range of available plants being the list of 400 advertised by Daniel Bunce in the Hobart Town Courier in July 1836.[17] From the earliest times there were native plants included in the plantings, the Norfolk Island Pine, Araucaria heterophylla, proving a favourite in both Sydney and Hobart.

Meanwhile from all the seed and plant material returned from the new colony had sprouted John Cushing’s The Exotic Gardener (1814) (Cushing was foreman gardener at Lee & Kennedy’s Hammersmith Nursery in London) which described ways to cultivate Australian native plants and there was later Robert Sweet’s Flora Australasica (1827-1828) with 56 coloured plates.

From illustrations of the time it can be seen that in the 1820s-1830s in Hobart and Sydney single-storey houses were set out in linear blocks of land, each with a front yard and back yard, the whole surrounded by a fence.

It was in the 1820s and 1830s that ornamental rather than subsistence gardening evolved in Australia with new introductions to the botanic gardens in Sydney (1816) and Hobart (1818). Compatriot Scotsman Alexander Macleay arrived in the new colony in 1826; he had been, like Loudon, a Fellow of the Linnean Society. In the same year Loudon produced the first issue of his Gardener’s Magazine (1826-1844) which was an invaluable source of horticultural knowledge, information, reviews and news about the activities of horticultural societies, keeping colonists up-to-date with the horticultural developments. Charles Fraser wrote to Loudon in 1828 with a List of Fruits Cultivated in the Botanic garden, Sydney which was published in the Gardener’s Magazine and there was also correspondence with James Anderson (collector for Hugh Low of Clapton Nursery) and others: seed were sent to him by John McLean (it was assumed that keen horticulturists would keep up-to-date by reading the Gardener’s Magazine).[7]

The first terraced vineyard in Australia was set out by Frederick Meyer (1790-1867) who brought Loudon correspondence to Australia in 1830. Australian residents contributed occasional articles to the magazine. John Thompson (c.1800-1861), a surveyor in Sydney and keen correspondent with Loudon was a landscape gardener who had worked on Hyde Park in London and also made suggestions for the improvement of Sydney’s Hyde Park, and published his illustrations of plants and trees of New South Wales and Tasmania.[8]

1830-1850 – First books

By the 1830s, with life more secure, publications begin to cater for local conditions and aesthetic considerations of landscape, grape-vines and the use of flowers and other ornamental plants begin to appear with the first three Australian books on horticulture by pioneering horticultural authors Shepherd (1835, 1836), Bunce (1838), McEwan (1843) along with the first nursery catalogue published by Dickinson (1844).

Publications of the 1830s included notes on local conditions intended to assist gardeners in a new land; they also introduce flowers and aesthetic considerations as ornamental gardening and more challenging crops begin to emerge from subsistence horticulture of vegetables, vines and fruit. Horticultural societies were founded in New South Wales and Tasmania, not for amateurs but more for the managers of large gardens and nurseries.

Australia’s first true book did not appear until Thomas Shepherd’s Lectures on the Horticulture of New South Wales of 1835. It was 80 pages long and delivered at the Mechanics School of Arts in Sydney and it described the cultivation of vegetables and fruits more comprehensively than the previous almanacs;[9] it appeared five years before America’s seminal A treatise on the theory and practice of landscape gardening, adapted to North America … (1841) by Andrew Downing and probably inspired by Loudon’s work.[10]

Another series of lectures was delivered the following year, Shepherd dying immediately after, the lectures being published posthumously in 1836 as Lectures in Landscape Gardening in Australia. It is quite likely that he was consulted in the setting out of the gardens of Elizabeth Bay House and Lyndhurst,[11] The Elizabeth Bay House occupying 20 men for several years and it included a botanic garden for a collection of exotic plants.

The third gardening book produced in Australia was written by the enterprising young Daniel Bunce who had arrived in Hobart in 1833, the 20-year-old taking over the Denmark Nursery. From July 1837 to June 1838 he produced monthly issues of his Manual of Practical Gardening, the 12 issues assembled into a 240 page book and notable for its inclusion of flowers, the first time for an Australian book[12] although his nursery collapsed and he sailed to the mainland seeking more propitious times in Victoria where he combined his horticultural business with writing, exploration and landscape design, advertising his nursery plants in the Argus (est. 1846 and closed in 1957) newspaper. Updates of his earlier publication were produced in 1850 and 1851.

Meanwhile settlement had begun in South Australia: not by convicts and people desperate for a new life but by wealthy gentlemen looking to establish business interests (such men were now found in Sydney and Hobart but they were relatively recent arrivals). T. Horton James published in1838 a garden calendar Six Months in South Australia … along the lines of Shepherd’s work while in 1840 George Stevenson produced Gardening in South Australia as an almanac-style publication but this was eclipsed in 1843 by George McEwin’s (Stevenson’s Scottish gardener) The South Australian Vigneron and Gardener’s Manual (reprinted in 1871 with a section on the flower garden and shrubbery added). McEwin established a successful jam and preserve factory and continued writing about South Australian horticulture, its vineyards and botanic garden, while his book discusses more unusual crops like tobacco, melons, bananas and pineapples and the possibility of orange groves on the Torrens (the first orange was brought out by Lieutenant Field in May 1837).[18]

In England gardening was booming with at least 16 new gardening magazines founded in the 1830s, although 12 of these ceased publication in the same period.[16]

The first known nursery catalogue was that of Hobart nurseryman James Dickinson published in 1844 and also known for his book written for Tasmanian conditions The Wreath … (1855) which leans heavily on Loudon’s work which was dominating the English gardening literature at this time.

1850-1860 – State Colonial Period

The 1850s Gold Rush resulted in a vast influx of people, each state growing rapidly as a separate colonial nation. With wealth and population came colonial competition and all the trappings of civic pride, a new confidence and more concentrated population. Australia had arrived, with stone buildings (classical colonnaded imperial-style in the cities), civic administration and parliament, transport systems, botanic gardens (Sydney est. 1816; Hobart est. 1818; Melbourne est. 1846; Adelaide 1854) and public parks, museums (Sydney est. 1827; Melbourne 1854), libraries (Sydney est. 1826; Melbourne est. 1854), universities (Sydney est. 1850; Melbourne est. 1853), scientific societies (Sydney Royal Society 1821,’Royal’in 1866; Melbourne est. 1854), theatres (Sydney’s Theatre Royal est. 1833; Adelaide’s Theatre Royal est. 1833; Melbourne The Pavilion est. 1841), art galleries (Sydney 1870s; Melbourne est. 1861) and the vibrancy of increasing local and international business, trade and manufacturing.

By the 1850s horticultural societies had become established in all states and their magazines and other publications were now another source of gardening information.

Improved communication with the ‘homeland’ meant that English tastes were keenly emulated in the colonies. It was now the writings of John Claudius Loudon that were setting the trends not only in Britain but also in America and Australia. Loudon was catering for the increased British affluence that had been spawned by the Industrial Revolution. There was now an affluent middle class, not just a landed gentry. Loudon catered not only for the picturesque tradition of eighteenth century country estates like those designed by Humphrey Repton and ‘Capability’ Brown but for his own ‘gardenesque’ (1832) style with a more formal use of exotic plants and acknowledgement of the presence of a garden with its physical and intellectual framework rather than direct emulation of nature: it catered for gardens on a smaller scale.

Wealth was displayed in horticulture through the increasing construction of villa gardens while the workers lived in more modest cottage gardens. With increasing demand for plants the nursery industry flourished, Sydney and Hobart beginning in the 1830s, Adelaide in the 1840s and Melbourne (including Ballarat and gold-mining centres) in the 1850s.[22] It was these nurserymen who created the horticultural literature of this period. Loudon’s ideas (along with those of Paxton, Glenny and others) undoubtedly played a role in Australia. They are, for example, referred to in Dickinson’s 1855 The Wreath, A Gardener’s Manual for the Climate of Tasmania.[19]

John Fawkner had brought seed and plants from Van Diemen’s Land when he set up in Victoria as a nursery followed by Bunce with his own nursery, landscape advice and private interests in exploration and Aboriginals. In 1851 he produced another edition of his book and married one of John Batman’s daughters, his second wife, who soon died leading him to a third marriage all the time writing in newspapers and journals in addition to his books.

In 1854 a new trend was established by the Smith, Adamson &Co. publication The Colonial Gardener … which was written like a seed and plant catalogue but with an introductory section of gardening information. A little later William Adamson published his (Brunnings) Australian Gardener of 1863 which has continued through many editions to the present day. It marked, perhaps, the founding of a certain horticultural independence from the mother country. George Bunning (George was the manager of the nursery J.J. Rule in Richmond, Melbourne) and family had become industry leaders and the Brunning’s catalogue was to become the gardening compendium of choice during the State Colonial Period.

In South Australia McEwin’s book was followed in 1857 by J.F. Wood’s The South Australian Horticulturist and Magazine of Agriculture, Botany and Natural History which provided both a rather different perspective and some interesting historical observations.

Even in the 1850s the major gardening was in gardens that could support gardeners or servants: for those not horticulturally literate who could not afford such labour there were books like that of nurseryman John Rule’s Economical Gardening for Cottagers: being Concise Directions for Cultivating Culinary Herbs (1859).

1860-1880 – Gardenesque

The archipelago of settlements was now becoming more integrated as railways and telegraph spread, and with increasing affluence from pastoral farming and the mineral boom of the gold rush it was sometimes possible to employ professional gardeners, usually British, who looked beyond the cottage garden style to more elaborate planting schemes for larger villa-style gardens.

It was a period when the grander and more formal gardenesque style was taking hold. Loudon had first used the term ‘gardenesque’ in his Gardener’s Magazine in 1832 to distinguish ‘arty’ gardens from the picturesque style that emulated wild nature. The gardenesque was a style loosely interpreted but in general it required close attention to pruning and thinning. It was applied on a large scale to sites like Centennial Park and the Sydney and Melbourne Botanic Gardens displayed plants separately and softened rectilinear elements to create artistic effect. On a smaller scale villa gardens would display colourful bedding schemes in lawns and include high Victorian garden ornaments and buildings. More affluent constructions like the Darling Point estate of Edward Knox included an ornate entrance, aviary, conservatory, flower beds with glass tiles, and Gothic cottage.[13] With an active Temperance Movement the moral benefits of gardening to the working man are frequently mentioned in literature of this period along with the ideas of self-improvement and lectures for working men offered at the Mechanics Institutes. Native-born sons were beginning to take over the businesses of their British fathers. New plants were being introduced in large numbers and Australian native species were now a distinct part of the garden mix.

To provide literature for these new demands books generally, often by English and Scottish nurserymen, took the form of the gardening manual, for example Richmond nurseryman T.C. Cole’s Gardening in Victoria … (1860). James Sinclair, a distinguished garden designer who from 1835 was writing articles for Loudon’s Gardener’s Magazine, had worked for Russian royalty laying out magnificent estates in the Crimea before arriving in Victoria in about 1855. He is well known to garden historians for his design of the Melbourne Fitzroy gardens. He produced his own Gardener’s Magazine (1855) soon renamed … Everyman his own gardener (1856) and in 1865 The Australian Gardener’s Chronicle … In Queensland John Hocking produced Queensland Garden Manual … (1865) and Flower Garden in Queensland (1875), in Tasmania, by several authors, A Handbook of Garden and Greenhouse Culture … (1870 and later editions), and in South Australia The Amateur Gardener by Ernst Heyne (1st edn ?1871), German friend of Mueller and employee of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens.

Specialist books were also appearing, the first book in Australia on roses, The Culture of the Rose (1866), was by Victorian, North Hawthorn rose nurseryman Thomas Johnson and it included a Preface written by Ferdinand Mueller.

Books now began to appear written by nurserymen outside the cities: The Cottage Gardener (1862) by George Smith of Ballarat, A Treatise on the Orchards and Garden of the Western Districts (1877) by J.W. Little of Bathurst.

1880 – 1900 – Cottage and Villa

In the decades leading up to the dawn of the 20th century though the cottage gardens remained increasing affluence saw the construction of substantial country residences especially in the Dandenong, Blue Mountain and Mount Lofty retreats of Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide. It was a period of horticultural expansion too.

To the nurserymen who made up the major proportion of garden authors in the 1860s and 1870s are now added the newspaper commentators. Prominent among these was H. A. James a correspondent with the Sydney Morning Herald who published a collection of his articles in Practical Horticulture for Australian Readers (1890) and followed this with the substantial 522-page and well-illustrated Handbook of Australian Horticulture (1892). In this book we have a magnificent compendium of social comment and horticulture for this period, including an exhortation for the greater use of Australian native plants in gardens.

Gardening books continued to be produced by prominent nurserymen including Law, Somner & Co. who had nurseries in both Sydney and Melbourne, producing Handbook to the Garden and Farm in Victoria (1880), the Sydney firm Treseder Bros. produced a general gardening book The Garden (1880) which went to several editions, and in Queensland there was The Queensland Horticulturist and Gardener’s Guide (1886) by Theodore Wright.

In 1889 John Gelding who had been the editor of the Horticultural Magazine, published Catalogue of Garden and Farm … a broad-based gardening book including the usual topics as well as florist’s flowers and a general plant catalogue.

E.W. Cole was an enterprising businessman known to all for ‘Coles Book Arcade’. He did well by selling small popular gardening information booklets for 1d each and having made a small fortune went on to produce, with some editorial assistance, Cole’s Australasian Gardening (1896), The Bouquet: Australian Flower Gardening (1910s) and The Happifying Garden Hobby (1918).

Specialist books included Practical Treatise on the Culture of the Rose (1891), Frank Fiendon’s The Australian Kitchen Garden (1897), Thomas Pockett’s Essay on the Cultivation of the Chrysanthemum … (1891, his biography was written by son John and published in 1958).

In the tradition of Adamson’s/Brunnings The Australian Gardener there now started the Yates’ Garden Guide (1890s) which has continued through tens of editions and with changed format, to the present day. Together it is perhaps these two books that have moulded, more than any others, the 20th century Australian garden ethos.[20]

At last Mrs Rolf Boldrewood broke the drought of female gardening authors by being the first woman to publish a gardening book in Australia The Flower Garden in Australia: A Book for Ladies and Amateurs … (1893), written in Albury after experience in a gardening family and setting up villa gardens in Sydney, Gulgong, Dubbo, Armidale, and then Albury as she travelled with her husband, the author Thomas Browne. Federation was to bring a new style of garden and garden writer.

1900-1920 – Federation

Inevitably, with connections by both road and rail as well as sea (although land connections with WA were yet to come), the various Australian States would unite and this occurred in 1901 to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Familiar publishing houses were now operating: Robertson & Mullins (Victoria), Angus & Robertson (Sydney), Walch (Hobart), and Rigby (South Australia).

Britain still dominated the scene as British goods and people flowed into the country and wool and wheat out. But British taste was changing from colourful bedding schemes to a new wild look of William Robinson and painterly approach of Gertrude Jekyll. And in Australia there was a new nationalism but for a kind of independence within the accepted tradition, Australia now producing its own cultivars of roses, chrysanthemums and daffodils and making an art of growing them under Australian conditions. Following English trends in Australia did not take long as things moved from the ‘Gardenesque’ to ‘Federation’ style and the first inklings of a search for an Australian identity in style.

Among the early promoters of a new style was the Principal of Burnley Horticultural College, Carl Bogue Luffman and his Principles of Gardening for Australia (1903) who was not keen on native plants. Gilmore Lockley was a writer for The Amateur Gardener (as ‘Redgum’) and he also wrote a popular book specialising in roses (1907) which went into several editions and another on dahlias (1908) and carnations (1914) while books of more general appeal also appeared like Scott Campbell’s Australian Home Gardening (1907), published by Dymock’s Book Arcade.

Botanic gardens were not to be forgotten and in 1911 Director of the Melbourne Botanic Gardens William Guilfoyle produced, with some foresight, Australian Plants Suitable for Gardens, parks, Timber Reserves etc. and later another garden writer Edward Pescott was to support the cultivation of native plants in The Native Flowers of Victoria (1916).

Vegetable gardening was not ignored as the 11 editions of Herbert Rumsey’s The A.B.C. of Australian Vegetable Gardening (1910-1941) demonstrated.

With World War I (1914-1918) few books were published, a notable exception being War Chest Flower Book (1917) by the War Chest Committee to raise money for soldiers at the front with individual sections on particular favourite plant groups written by eminent professional gardeners of the day.

1920-1940

Gardens of the 1920s to ‘40s remained gardenesque in general style, adjacent to the many bungalows that displayed neat lawns and collections of roses: they do not reflect familiar social and artistic forces of the day, the depression, Art Nouveau and Art Deco, jazz. Native plants are getting more attention but it is the suburban garden of annuals, roses and lawn on the bungalow block that seems to be central.

Following Roman tradition the rose reigned over English gardens (witness the War of the Roses) passing to the British colonies where they were grown around the worker cottages, the first book in Australia dedicated to a single genus, Rosa the rose, published in 1866.[14] However,in Australia it really gained in popularity after WWI following the development of the tea Rose in England and the Australian rose specialist Alister Clark. Crittenden refers to a post-war English ‘revival’ reaffirming the solid security of the British connection, the reliability of British products, the English themes on calendars, paintings and Christmas cards, a conviction of early settler nostalgia for English gardens, and a surge of oak plantings in the 1930s.[15] Centre-stage was the show-plant the rose which featured in books like, in 1920, The Australian Rose Book: A Complete Guide to Rose Growers by R.G. Elliott followed in 1930 by Modern Roses in Australasia… by B. Vincent Rossi. It was the period of Art Deco and the ‘modern’ and in 1931 by Edward Pescott’s Rose Growing in Australia which was part of specialist gardening series to which Pescott added books on the dahlia, bulbs, and native plants.

In 1935 Harold Sargeant, one of a new breed of horticultural journalists in a period when gardening magazines were becoming established, published Flowering Trees and Shrubs setting a new garden emphasis and including a chapter on native plants. A monthly magazine The Australian Garden Lover was launched with Jean Galbraith a columnist writing under the pen-name Corea.

Popular gardening books were now proliferating so there was a wealth of general gardening advice, including consideration of the vegetable garden, was becoming available.

1940-1950 – War

Deprivations of WWII from 1939-1942 meant that once again, as occurred at settlement and WW1 emphasis was on subsistence as food plants took centre stage. Lawns and flower gardens were dug over to make room for vegetables and a decade of food gardening books were published by the gardening correspondents of the ABC and Sydney Morning Herald as people were encouraged to ‘Dig for Victory’.

Roses remained popular but in 1943 the English immigrant Edna Walling penned Gardens in Australia: Their Design and Care. It was the first work of a naturalistic designer who was to become widely respected. With designers like Gertrude Jekyll and William Robinson as models she placed the English gardening tradition and village life in an Aussie setting. Her first book was followed by the popular Cottage and Garden (1947), and A Gardener’s Log (1948).

1950s – Post-War

In the 1950s Australian immigrants no longer came almost exclusively from Britain, now there was an influx of Greeks, Italians, Poles and Germans and corresponding shift in long-held British traditions. Wealth increased across society with an economic recovery after the deprivations of WWII and this, combined with the increasing population, saw the emergence of suburbia, not only in Australia but across the western world. There was now more home-ownership, a change in the kinds and proportions of vegetables and fruits eaten and decreasing use of annual bedding plants. There is a new approach to outside living as swimming pools, BBQs and courtyards begin to appear and a distinctly American influence can be seen especially in the similar climate gardens of California. Gardening books increase in number as we near an era where numbers become overwhelming. Crittenden points out the influence of a greater choice within the media, not only newspapers and periodicals, but the increasing influence of radio and television with the emergence of media personalities who now become prominent in the horticultural literature like broadcaster Reg Edwards and The Australian Garden Book … (1950) but also keen specialist interest in roses with Alfred Thomas’s Better Roses and books on orchids.

21st century

With the opening of the 21stcentury the end of books and periodicals seemed a possibility as people turned their attention to computers and the internet, to new communication channels like Facebook and Twitter. In 2012 Australian Horticulture (Aussie Hort) folded in July 2012 after 109 years, and was quickly followed in 2013 by the periodical Burke’s Backyard which lasted from July, 1998 to March 2013.

Nineteenth century horticultural literature

This list is adapted from the paper by Spencer, R.D. & Cohn, H. 1986. ‘Nineteenth century horticultural literature. Appendix 2’ in Historic Gardens Conference, ‘Rippon Lea’ 16 April 1986. Ministry for Planning & Environment and Historic Buildings Council. It is a general guide only with the focus on Victoria and the reader is directed to the work of Victor Crittenden (1986) for a more in-depth coverage.

Much of the literature influencing Australian garden design, landscaping and management, including the selection of plant material, would have been European, such as that arriving in Australia from Britain. However, there is a need to document the horticultural literature produced in Australia in the nineteenth century, since this no doubt reflected more directly the attitudes and intentions of the early settlers.

The following is a list of literature which would have been broadly available, and which has been traced by the Melbourne Herbarium Library. It is not a comprehensive list but the basis of compilation being undertaken at the Melbourne Botanic Gardens. Nursery catalogues and lists of botanic gardens holdings are not included. Only the more substantial periodicals and books which illustrate the tastes of the time or which may have exerted some influence on the development of horticulture in the State have been included.

Timeline

1806 – Howe, G. (1806) New South Wales pocket almanack and colonial remembrance. Contains the Aust. Gardening guide, Repr. Mulini Press, Canberra, 1980.

1828 – Fraser, E. (1828) Catalogue of the fruits cultivated in the Government Botanic Garden at Sydney, New South Wales. Gardeners magazine 5: 280.

1835 – Shepherd, T.W. (1835) Lectures on the horticulture of New South Wales, Sydney. William McGarvie,

delivered at the Mechanics School of Arts, Sydney.

1836 – Shepherd, T.W. (1836) Lectures on lands cape gardening in Australia. W. McGarvie, Sydney

1838 – Bunce, D. (1838) The Australian manual of horticulture. Hunter, Melbourne. Later editions: 2nd 1850; 3rd 1851; 4th 1857.

1838 – Bunce, D. (1838). Manual of practical gardening adapted to the climate of Van Diemen’s Land .. W.G. E11liston, Hobart Town.

1843 – Macarthur, W. (1843) Catalogue of plants cultivated at Camden. Welch, Sydney. Other editions: 1845, 1850, 1857

1843 – McEwin, G. (1843). South Australian vigneron and gardeners’ manual. James A1len, Adelaide.

1845 – Dickinson, J. (1845) Catalogue of annual and herbaceous plants. W.M. Gore

E1liston, Melbourne.

1854 – Smith, Adamson & Co. (1854) The colonial gardener, being a guide to the routine of gardening in Australia … Goodhugh & Trembath, Melbourne.

1855 – Dickinson, J. (1855) The wreath: a gardener’s manual, arranged for the climate

of Tasmania. Ed. J. Morgan. “Colonial Times” Office, Hobart.

185? – Sinclair, J. (185?). Beauties of Victoria in 1856 containing notices of two hundred of the principal gardens round Melbourne (Melbourne?) (Melbourne?)

1856 – Wood, J.F. (1856) The South Australian horticulturist and magazine of agriculture, botany and natural history. S.E. Roberts, Adelaide.

1857 – Sinclair, J. (1857?) Everyman his own gardener. Bound Manuscript. (c. 1866)

1859 – Australian gardener: being a complete system of gardening practices in

Victoria. The earliest edition so far traced is the 4th of 1859 and was probably issued by Smith and Adamson, Nurserymen of Melbourne. Subsequent editions, with a slightly variant title, were written

by W. Adamson. Still later editions were edited by other people, among them being A.C. Sturrock and F.H. Brunning. Similarly, later editions became known as “Adamson’s Australian gardener” and

been ascertained, other “Brunnings Australian gardener”. As far as has editions to 1900, are:

5th, 1860; 6th, 1862; 7th, 1863; 8th, 1872; 9th, 1875; 10th, 1879; 11th, 1884; 12th, 1888; 13th, 1891; 14th, 1896.

1859 – Sinclair, J. (1859) Australian gardenrs’ chronicle, or calendar of operations for every month of the year in the kitchen garden. Melbourne.

1859 – McMi1lan, T. (1859) Rule’s economical gardening for cottagers … J.J. Rule, Melbourne.

1860 – Cole, T.C. (1860) Cole’s gardening in Victoria; containing full directions for the formation and general management of a good garden W. Fairfax, Melbourne.

1860 – Colonial handbook for farmers and gardeners (1860) Victorian Agricultural and Horticultural Gazette Office, Geelong.

1862 – Smith, G. (1862). The cottage gardener: comprising the kitchen, fruit and flower garden … Comb & Co., Ballarat.

1866 – Johnson, T. (1866) The culture of the rose. Blundell & Ford, Melbourne. This is a 3 vol. 32 page catalogue of about 150 roses, mostly old hybrid perpetuals. It contains a preface by Mueller written from M.B.G. Sept. 12, 1866

1869 – Lang, T. (1869) List of garden implements. Melbourne.

(?1870) – Law, Somner & Co. (?) Handbook to the garden for New South Wales. W. Maddock, Sydney. Later edition, (n.d.) Anderson, Hall & Co. Sydney.

1864 – Law, Somner & Co. (1864). General catalogue with calendar of gardening operations. Clarson, Shallard & Co., Melbourne.

1867 – Law, Somner & Co. (1867) Live fences: the osage orange and other hedge plants. Law, Somner, Sydney.

1870 – Walch, J. & Sons (1870) Hand book of Garden and Greenhouse Culture in Tasmania. J. Walch & Sons, Hobart.

1875 – Mackay, A. (1875) The semi-tropical agriculturist and colonist’s guide: plain words upon station, farm and garden work, housekeeping and the useful pursuits of colonists. Slater, Brisbane. Other editions: 2nd 1890; (3rd) 1897.

1879 – Sturrock, A.C. (1879) The Australian gardeners’ guide: an epitome for the colony of Victoria. New edition. G. Robertson, Melbourne.

1879 – Hylde, R.T. (1879) On annuals, basket plants and climbers. Adelaide

1880 – Treseder Bros. (1880) The garden. A.W. Beard, Sydney. 2nd ed. by J.G. Treseder (1884) C. Jerrems, Sydney.

1871 – Heyne, E.B. (1871) The fruit flower and vegetable garden. Andrews, Thomas & Clark, Adelaide. Later editions under the title “The amateur gardener of the fruit, flower and Vegetable Garden: 2nd 187?, 3rd 1881 4th 1886

1878 – Crichton, D. (1878) The Australian horticultural magazine and garden guide.

Melbourne.

1880 – Brown, J.E. (1880). Report on a system of planting the Adelaide park lands illustrated by plans

and sketches. R.K. Thomas, Adelaide.

1881 – Brown, J.E. (1881) A practical treatise on tree culture in South Australia. Government Printer, Adelaide. Later editions: 2nd 1881 (reprint of 1st); 3rd 1886

1884 – Handbook of garden and greenhouse culture in Tasmania. (1884) 2nd ed Hobart.

1880 – Law, Somner & Co. (1880). Handbook to the garden and farm for Victoria, Law,

Somner, Melbourne.

1889 – Law, Somner &Co. (1889) Handbook to the garden and the farm, a guide to Australian

cultivators. Melbourne

1886 – 1907 – Campbell, W.S. (1907) Australian home gardening: flower and vegetable tables. Sydney.

1886 – Clarson, W. (1886) Kitchen garden and cottagers manual. Melbourne.

1890 – James, H.A. (1890) Practical horticulture for Australian readers. Turner and Henderson, Sydney.

1891-1892 – James, H.A. (1891-2). Handbook of Australian horticulture: in twelve monthly parts. Turner and Henderson, Sydney.

1893 – Browne, M.M. (Mrs Rolf Boldrewood) (1893) The flower garden in Australia. Melville, Mullen & Slade, Melbourne.

1893 – Mortlock, J.J. (1893) Australian amateur gardener. George Robertson, Melbourne. Amateur series, no. 3.

189? – Young, A. (189?) The New South Wales gardener: a handbook to the garden. Anderson & Co., Sydney.

1896 – Eliott, W. (1896) Cole’s Australasian gardening and domestic floriculture.

Cole. Melbourne. Later edition: 1903.

1897 – Yates, Arthur, & Co. (1897) Hints for amateurs: Yates gardening guide for Australia and New Zealand. 3rd ed. Yates, Sudney & Auckland.

1900 – Clarson, W. (1900) The flower garden and shrubbery with directions as to the management of the bush house, fernery, conservatory and other ornamental and useful home surroundings of the cottage and villa Anderson & Co, Sydney. 9th ed. Rev. by F. Hannaford. A.H. Massina & Co., Melbourne.

Cole, E.W. (n.d.) Cole’s penny garden guide: what to do each month in the flower, fruit and kitchen garden . E.W. Cole, Melbourne.

1903 – Luffmann, C.B. (1903) Principles of gardening for Australia. “Book Lovers Library”, Melbourne.

1910 – Guilfoyle, W.R. (1910) Australian plants, suitable for gardens, parts, timber reserves. Whitcombe & Tombs, Melbourne.

Periodicals

1875-1940 – Garden and field, v. 1-64(12); 1875-1940 Adelaide and Melbourne

1902-1903 – Garden gazette. July 1902-September 1903 Melbourne.

1855-1856 – Gardener’s magazine and journal of rural economy. Ed. J. Sinclair. v.1(1-11); 1855-56. Melbourne

1877-1878 – Horticultural magazine and garden guide. v. 1-2(12); 1877-78. Later Australian horticultural magazine and garden guide.

1864-1871 – Horticultural magazine and gardeners’ and amateurs’ calendar, containing the transactions of the horticultural Society of Sydney. v.1, 1864 continued to at least 1871. Sydney.

1857-1861 – Victorian agricultural and horticultural gazette. v.1-5(13), 1857/8-61. Geelong.

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

There is a broad pattern in the development of the Australian genre of horticultural literature starting with the mostly English books that had been brought out with the First Fleet, the most popular plant books probably relating more to agriculture than gardening. The first local publication consisted of garden notes published in 1806 using an old printing press that had been brought out with the First Fleet.

It was only during the 1820s and ‘30s that settlers move from subsistence gardening to ornamental horticulture after the establishment of the Sydney and Hobart Botanic Gardens and the introduction of ornamental plants by wealthier garden lovers like Alexander Macleay. It was now that the first gardening books appeared along with, in 1844, the first nursery catalogue

With increase in population and affluence resulting from the gold rush and a successful pastoral industry Australia was gaining self-confidence, taking seriously the business of adapting the fashions of Britain to the local environment. The number of publications was increasing and magazines were testing the commercial market.

Early gardening in Sydney and Hobart was a matter of subsistence cultivation of vegetables and fruit and although there were a few large houses, including Government House, that were able to indulge in some landscaping and plant collections, most consisted of simple front-yard, back-yard blocks. Settlement horticultural literature reflected basic needs consisting first of practical, more agricultural, guides brought out from England until 1806 when the first local literature was produced in this Early Colonial Period consisting of informative almanacs along with the seed list, plant lists and articles printed in newspapers.

Horticultural literature is peripheral to sustainability except insofar as it is part of the network of communication spreading ideas and knowledge that can be applied in ways that can affect social organisation and resource use.