Persian & Islamic gardens

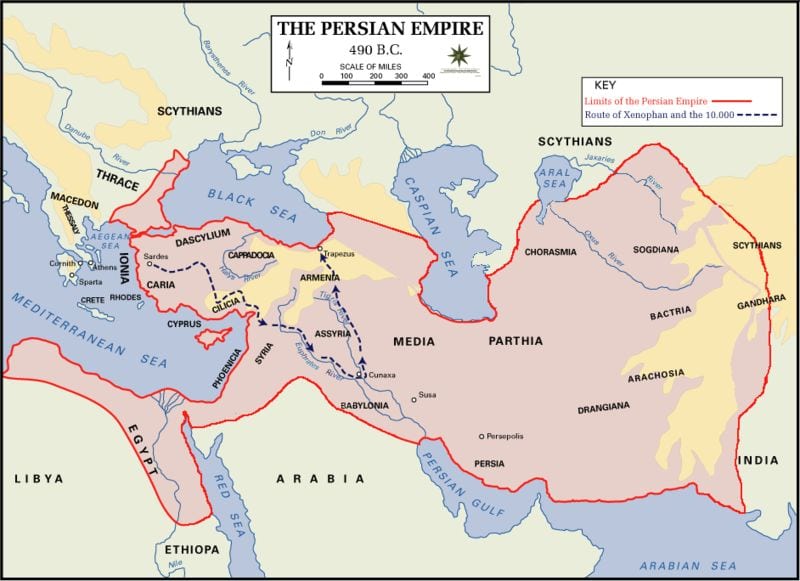

The First Persian or Achaemenid Empire c. 490 BCE

at the height of the reign of Darius the Great

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Useful background can also be found in Wikipedia on both Persian Gardens and Islamic Gardens.

Introduction – Islamic Gardens

Following the great ancient empires of Egypt and Mesopotamia there emerged in Persia, on what is now the Iranian plateau, a new and vast eastern empire that, at its height in about 490 BCE, would engulf both Mesopotamia and Egypt. This was a cosmopolitan culture on the trading route that ran between China and India in the east, and the Mediterranean countries of the west. Along the silk road passed salt from Arabia and spices from the orient. The major arterial connection through Persia was a surfaced ‘Royal Road’ built by Darius I (c. 550–486 BCE) which extended from the Persian heartland to the Aegean coast, a distance of about 2700 km and a journey that could, if necessary, be completed in seven days on horseback by picking up fresh horses at the many roadside rest stations on the long journey that passed through forests, over mountains and across major rivers.

Though finally defeated by the Greek forces of Alexander the Great this Persian culture had excelled in hydraulic engineering and architecture and also demonstrated both religious tolerance (freeing the Jews from Babylonian tyranny) and humane treatment of subjugated peoples.

Persians had a deep respect for gardens, the beautiful and formal designs that so impressed the invading army of Alexander the Great and his generals that on return to Greece the new-found Persian ideas would be incorporated into private gardens and public space in the new Greek empire, most notably the layout of the new city of Alexandria designed by Alexander himself when his forces recaptured Egypt.

Persian influence on modern gardening is strong, emerging from ancient Mesopotamian traditions to pass into Persian culture before being absorbed into the Islamic tradition. But it was also a source of ideas for the conquering Greek army of Alexander the Great whose Hellenistic generals built villa retreats that were later emulated and embellished by the Roman elite to subsequently play a role within the general western gardening tradition.

Historical context

An empire in the region of present-day Turkey was founded by the Hittites and lasted from about 1800-1200 BCE, eventually collapsing in about 1180 BCE parts of the country being conquered and settled by the Assyrians notably the most famous of the Assyrian kings, King Sennacherib, creator of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. However, some parts would hold out until about 612 BCE.[7]

There were three Persian empires: Aechmenid (550-330 BCE); Parthian (247-224 BCE) and Sasanian (224 BCE-651 CE).

The First Persian Empire, perhaps better known as the Achaemenid Empire lasted from about 550–330 BCE, founded by Cyrus the Great (c.600 or 576-530 BCE) but named after King Achaemenes who had ruled from 705 to 675 BCE. The empire had been preceded in the period 728-550 BCE by Median kings renowned for their hunting parks. By 539 BCE Cyrus, who reigned from 559 to 530 BCE, had subjugated the Neo-Babylonian empire and he was followed by the equally ambitious Darius the Great (r. 522-486 BCE) who further extended this empire from Egypt in the west to the Indus valley in the east to make it the world’s largest ever empire to that date. Babylon now became the administrative capital of the Persian Empire which was, in effect, the known European world. Commerce and art thrived in this vast empire for more than two centuries, surviving until 334 BCE when it succumbed to the invading army of Greek Macedonian Alexander the Great.

The clash between Greeks and Persians marks an east-west cultural divide that has dogged the world to this day, the Greek, Roman and Christian tradition of the ‘West’ and the Persian, Islamic and Byzantine tradition in the ‘East’. Persian horticulture and garden design had reached a sophistication far beyond that of the Greeks and would win the deep respect of Alexander and his generals on their Persian campaign.

Greeks and ancient Persians were bitter enemies. Greek historian Xenophon (430-354 BCE) was a mercenary soldier whose cogitations about Greek and Persian Empires at this time are recorded in his Anabasis, an account of an early military campaign against Cyrus the Younger (?-401 BCE). Xenophon’s experiences were keenly read by the young Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) as preparation for his conquest of Persia. Xenophon gives us a detailed description of the gardens of Darius the Great (c. 550–486 BCE). Cyrus the Younger (?-401 BCE), son of Darius II, is noted for an enclosed park at Sardis (western Turkey) visited by Spartan Greek General Lysander who had recounted his experiences to Xenophon. Lysander was amazed by the magnificence of the garden, its formal rows of fruit trees, and the scent of flowers. Later, when Alexander in the fourth century BCE marched with his armies through Persia he and his generals were also deeply impressed by the sophistication and magnificence of the gardens they encountered in the regional palaces.

Zoroastrianism & Islam

Ancient Persians followed the teaching of the religious philosopher Zoroaster (also known as Zarathustra) who lived about 1,000 BCE. Zoroaster’s thoughts were recorded in a holy book known as the Avesta but only a few parts of this book remain. Zoroastrianism, regarded as the world’s first monotheistic religion, was also the official religion of the Sassanid Empire, the final pre-Islamic empire that persisted from 224-651 CE contemporary with the Roman Byzantine Empire. The deep religious symbolism so characteristic of the Persian garden probably dates back to at lest these times.

Islam is the most recent of the three monotheistic Abrahamic religions (the others being Christianity and Judaism) that arose in the 7th century CE following the teachings of the prophet Muhammad (c. 570-632 CE) from Mecca who united Arabia with the religion of Islam which is the word of God as revealed to Muhammad and written in the holy text the Quran. The Quran and holy texts feature descriptions of paradise using garden imagery. Within a century of Mahammad’s death Islam had spread through Mesopotamia and Egypt, the first Caliph Abu Bakr insisting that, since the Quran taught that the natural world was sacred, his soldiers must protect all nature during his military campaigns.[4]

Persian gardens

Royal pleasure gardens of ancient Persia were enclosed oases of peace and tranquility, with fruit trees, fragrant flowers, cool shade and luxuriant vegetation. As havens from the piercing heat and barren dusty plains outside, the water they contained symbolised both life and purification. Pools and fountains provided relaxing sound, reflections, and humidity as a place for relaxation and ceremony.

The ancient Persian word pairidaēza refers to an enclosure, park, or hunting ground and is related to the later Greek word paradeisos and subsequent Christian associations with the garden of Eden as an idealised place of eternal serenity and bliss, a retreat from civic duty and a ‘heaven on earth’.

The pairidaēza of the Median kings[5] were were imbued with a rich symbolism. Number four was sacred, being a symbol of, amongst other things, the four basic elements of the world: earth, air, fire and water. Gardens generally divided into four with a palace in the centre.

From the third to the seventh century Islamic gardens, called chahar bagh, were also divided into four equal parts symbolising the four rivers of paradise (this also being a feature of the Hebrew Eden as described in Genesis) which were said in the holy scriptures to originate from a central source or spring of life. Sometimes one axis was longer than the cross-axis, and water channels through the four gardens united at a central pool or feature.

Exemplary Persian gardens include those of King Darius the Great and Cyrus the Younger (d. 401 BCE). Excavations from the period 500-600 BCE have revealed pavilions, ponds, and watercourses, walls, trees, trellises, and inner courtyards.

The spectacular male peafowl or peacock, though native to India, was kept by royalty in both ancient Babylon and Persia, its image engraved on royal thrones. In Islamic tradition and Sufism the peacock is associated with Satan. In Greek mythology the goddess Hera was drawn in her chariot by peacocks, although the bird only became known to the ancient Greeks during Alexander’s military conquests, Aristotle referring to it as the ‘Persian bird’. To this day it is kept on large estates where its distinctive call announces its presence to visitors who, like people down the ages, gather to admire its dignified strutting vanity and breathtaking iridescent tail-fan displays.

There is a continuity of tradition between the early quadripartite hunting grounds of Persian kings, the later chahar bagh gardens, and Islamic courtyards that display an axial pool.

Islamic gardens

In the Quran it is the image of an ancient Persian-style garden that greets the believer in the afterlife, a garden or djanna, a palace garden or funererary complex (like the Taj Mahal) ‘ … of delights – four rivers of water, wine, milk and honey, lotus trees without thorns, laden banana trees, shade trees, pomegranates, palms, fountains and pavilions, golden brocade settees, beautiful youths and virgins.’[2] Gardens with these ancient Persian themes could be found from Spain to north-west India spanning a period of about 1,000 years.

A new phase of the Persian garden began around 637 CE when Arabs overran Iran introducing the new Muslim faith and then extending the Arab empire through Syria, Egypt and north Africa followed by Spain, Asia Minor and Turkey. The Persian garden was the foundation of the Muslim gardens which, being mostly in countries of similar climate to Iran have retained the basic Persian garden elements to the present day emphasising Muslim tawhid , the divine unity or perfection manifest in the harmony and equilibrium of all the garden elements. The courtyard of the Prophet Mohammad’s house at Medina c. 622 CE, now partially reconstructed, is possibly the first Islamic garden.[2] Courtyard gardens so characteristic of Islamic countries are also found in medieval Andalusian Spain, in Persia after 1300 CE and Moghul India from 1400 CE.

By about 830 CE Baghdad had become amajor European centre of learning where ancient Indian and Greek manuscripts were translated into Arabic. Islamic gardens were introduced to Baghdad in the 8th century (a centre of trade and learning at the time).

Moorish Spain

In 711 Muslim Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula from Morocco, entering the Iberian Peninsula and calling their new territory Al-Andalus (Andalusia) a region which, at its height, included today’s Gibraltar, most of Spain and Portugal, and parts of southern France and ending with the fall of Granada to Christians in 1492. Garden historian Harvey lists the plants cultivated in southern Spain through the period 1050-1200 CE. Andalusia under the western Caliphate of Cordova (929-1031 CE) was a cultural centre of Europe with its capital in Cordoba but breaking up into succession states in 1031, the most notable being Seville and Toledo where ‘botanic gardens’ (huerta) were established.[6][8] For a while Cordoba became a Mediterranean centre for agriculture and production horticulture the surrounding irrigated land planted with vineyards and orchards. Ibn Bassal was a Moorish botanist in Toledo and Seville who wrote a major technical work on horticulture c. 1085 CEwhich would serve as a basis for further works produced in Seville such as the Kitab al-Filaha (Book of Agriculture) a master work by Ibn al-‘Awwam in the late 12th century and Ibn Lyun’s Treatise of Agriculture in 1348. A Christian invasion was repulsed in the 13th century.

Islamic gardens are also found in Turkey and North Africa. On the dry Central Asian Iranian Plateau of Samarkand (now Uzbekistan) Mongol ruler Tamerlane had by 1404 created a magnificent garden oasis, other similar gardens were established elsewhere notably that at Herat (now Afghanistan) constructed by his son.

Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal (Persian – the Royal Grounds or Crown of Palaces) in Agra, India is an excellent example of a Persian garden as interpreted by Mughul emperors, Muslim descendants of both Genghis Khan and Tamerlane who, at the height of their power in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, controlled most of the Indian subcontinent. The architect was an Iranian Ostad Isaa Afandi and the structure was built by Persian stone masons using white marble imported from Isfahan, Iran according to the ancient Persian cosmic symbolism oftem employed in the four-fold chahar bagh style. Raised pathways divide the four quarters into 16 sunken parterre flowerbeds and representing the four rivers of paradise (also a feature of the Hebrew Eden) emerging from a central source as described in holy Islamic texts. There is a marble water tank in the middle of the garden (in other gardens this maybe a tomb or mausoleum) and is a reflecting pool running along the north-south axis that picks up the reflection of the main building, a mausoleum. There are also fountains and avenues of trees. It was completed 1648.

Persian Garden (pic)

http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/garden/

Plants

See also Phases of plant introduction

For western Europe it was the Muslim gardens of the region between the Middle East, India and the Balkans that were the source of plants during the first major phase of European plant importation beginning in the mid sixteenth century. Collectors returned plants mainly to Antwerp, London, Paris and Vienna and this was associated with considerable technical horticultural expertise. It was only in the late sixteenth century that European scince began to match that of the Muslim world.

Plant imports included fruit trees, palm and pomegranate, a rose garden. The Oriental Plane or Chenar features and may symbolise the Tuba tree of the Koran. According to historian Wendy Pullan:

Many of the flowers well known in Western gardens are found in Islamic gardens: bulbs, such as narcissi, tulips, grape hyacinth, and lilies; small flowers, such as carnations, violets, amenones, poppies, and cyclamen; and flowering shrubs and vines such as jasmine, honey-suckle, and passiflora. But roses have a long history of being most admired, and rose gardens (gulistan is the widely used Persian term) remain common. The rose (gul) pervades much of Islamic culture in perfumes and rose water used for scent and as a gastronomic ingredient. Persian and Arabic poetry is filled with metaphors based on the beauty of this flower, and painted tiles often depict it along with other favourite blossoms.[3]

Trees and flowers are used generally in the Islamic arts, the use of floral motifs being especially popular in carpets.

The famous garden of Cyrus 1 in the 6th century BCE was planted with fruit and cypress trees, the flowers including roses, lilies, jasmines and exotic grasses. Arrian has described the gardens as ‘a grove of all kinds of trees . . . with streams . . . ‘ and encompassed by a large area of ‘. . . green grass’ (Arrian, Expedition of Alexander, VI, 29). This Pasargardae garden was a blend of Iranian (Medo-Persian), Anatolian (i.e. Ionian) and Mesopotamian civil engineering features and foreshadowed those in the Persopolis city-palace and other Achaemenid sites.

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

Gardens have seemingly throughout history received the respect of social elites as peoples of the world competed with muscle and might on the literal battlefield while flaunting their sophistication and urbane sensitivity through their gardens. Greek author Xenophon in his Oeconomicus describes how the King of Persia considered the art of war and plant husbandry as ‘two of the noblest and most necessary pursuits‘ ensuring that there is at least one fine paradeizos in each of the districts of his realm.

Sophisticated Muslim landscape horticulture combined with its scientific and technical innovation preceded and provided the impetus for that of later Western horticulture. Only in the sixteenth century did western European science begin to catch up with that of the East.

Key points

The theme of gardens as peaceful retreats away from the concerns of civic duty, possibly inherited from the gardens of Mesopotamia, finds echoes in the hillside retreats of Greece, Rome and later British empire. In Australia the wealthy enjoyed the cool hillside gardens of the Dandenongs outside Melbourne, the Lofties outside Adelaide, and the Southern Highlands outside Sydney.

General design elements

- Persian (Iranian) gardens epitomise the oasis of peace and tranquillity with cool shade and luxuriant vegetation, a haven from the piercing heat and barren plains of the desert-like country outside

- Elements include: symmetry within a rectangular walled boundary; gateways on the main axis; pavilion or palace at centre of pools intersecting at right angles; pools (filled to the brim) and fountains, waterfalls, channels and other water features; terraces (on sloping sites); paths often lined with trees, shrubs and/or and flower beds; major vistas leading to pavilions, gates or vaulted recesses; straight paths; fragrant flowers; fruit trees and shrubs. To manage sunlight there were pavilions, walls, trees, trellises, and the inner courtyard

- Male peafowl or peacock, though native to India, was kept by royalty in both ancient Babylon and Persia, its image engraved on royal thrones

- The rose is prominent in Islamic culture as elsewhere in the ancient world, for its perfume and rose water. Persian and Arabic poetry is filled with rose metaphor and painted tiles often depict its form

Caliphates

Rashidun – 632-661

Umayyad – 661-750

Abbasid – 750-1258

Ottoman – 1517-1924