Philip Miller

Chelsea Physic garden

Founded in 1673 with the typical formal layout of medicinal plant physic gardens of the period

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – July 18 2006 flickr-rickr Accessed 23 June 2017

The introductory article Plant People sets the scene for the selection of plant people described in this series of articles, placing them within a global and plant science context. For a more extended discussion of changes in the form and context of plant study over time see the history of plant science.

Introduction – Philip Miller

Scottish Quaker Philip Miller (1691-1771) was Praefectorius (Curator) of London’s Chelsea Physic Garden (also known as The Physic Garden of the Apothecaries of London) and a horticultural figurehead of the early English Enlightenment.

Miller’s significance for Australia, and Western horticulture in general, lies in the role he played in consolidating the horticultural traditions passed on from antiquity (especially that of plant introduction) which would be emulated in the later gardening practices of the Neo-Europes America, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, parts of South America and India, and other outposts of the British Empire.

Miller was one of a group of important Quaker plantsmen of the day, friends that included John Fothergill (1712-1780), Peter Collinson (1694-1768), the American botanical collector John Bartram (1699-1777), and Scottish society nurseryman James Lee (1715-1795) of the Hammersmith Vinyard nursery who employed the (also Quaker), botanical artist Sydney Parkinson (b. ?1737). Parkinson was later appointed botanical artist on Cook’s first circumnavigation of the world in HMS Endeavour. This group of men undoubtedly had a collective influence on the path of Joseph Banks’s botanical career.[34] Collinson had an impressive garden at Ridgeway House, Mill Hill, London which passed to botanist and first honorary secretary of the Horticultural Society Richard Salisbury (1761-1829) who subsequently fell out with his botanical colleagues, accused of plagiarizing Robert Brown’s work. In 1762 Fothergill started collecting warm climate plants in his garden at Upton Park, Stratford which totalled some 3400 species, competing in number at that time with not only the Chelsea Physic Garden but Lee’s nursery, and Kew.[34] Lee published the first English adaptation, in six editions, of Linnaeus‘s work.

Early life

Philip Miller was born into a family of nurserymen. His successful father, who had arrived in London from Scotland in the late 1600s, ran a highly profitable market-gardening business which allowed him to provide his son with an excellent all-round education in languages and science. Before Philip’s appointment to the Chelsea Physic Garden he had travelled around both England and the Low Countries. In London and the area around Chelsea nurserymen had been well established for many years but it was very different from today. Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), a Swedish ‘apostle’ of Linnaeus and collector of plants from North America visited the Chelsea Physic Garden in the latter part of the eighteenth century noting that Chelsea was a little village a couple of miles from London where the Thames meandered between large numbers of competing nurseries and market gardens.[24]

Working first in his father’s market garden at Deptford on the south bank of the Thames in southeast London Miller subsequently set up his own florist and ornamental shrub business in St George’s Fields, Pimlico.[2] A successful and hard-working nurseryman and businessman Miller was recommended in 1723 for the position of Head Gardener of the Chelsea Physic Garden to the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries by the influential Hans Sloane, later founder of the British Museum.

The man

Miller was:

‘A solid, red-faced man … combative and difficult … but a brilliant experimental gardener’[14]

‘A man who always dressed in ‘plain old-fashioned English dress’ and who eschewed wigs, ruffles and other fanciful attire … He believed that daily exercise and an outdoor life cleansed and strengthened the body …’[1]

Miller had two sons, one of them, Charles, becoming the first Head Gardener of the Cambridge Botanic garden.

An excellent biography The Chelsea Gardener Philip Miller 1691-1771 has been written by Hazel Le Rougetel and it includes an insightful discussion of Millers contribution to botanical science written by botanical historian William Stearn.

Chelsea Physic garden

The oldest botanic garden in Great Britain is the Oxford Botanic Garden which was founded in 1621 as a physic garden growing plants for medicinal research. Jacob Bobart the Elder (1599-1680) was appointed the first Director (Hortus Praefectus) succeeded by his son Jacob Bobart the Younger, a keen botanist and contributor to the second edition of the Oxford Botanic Garden ‘Catalogue’ in 1658 (following the first edition of 1648). He was a keen plantsman who built up the collections, exchanging seed with a wide range of eminent botanists of the late-17th and early-18th centuries, notably William Sherard (1659-1728), Hans Sloane (1660-1753), John Ray (1627-1705) and the Duchess of Beaufort (1630?-1714). Working with Robert Morison (Professor of Botany at Cambridge) (1620-1683) he completed the third part of Morison’s Plantarum Historiae Universalis Oxoniensis in 1699.

Today the Oxford Botanic Garden contains over 8,000 different plant species on 1.8 hectares (4½ acres).[25] John Tradescant the Elder (c. 1575-1638) was one of the first recorded English gardeners and he worked for both Sir Robert Cecil of Hadfield House and Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I. In 1637 he was appointed keeper of the Oxford Botanic Garden but died in 1638. Tradescant and his son John the Younger (1608-1662) are seminal figures in England’s horticultural history and are now buried at St Mary’s-at-Lambeth the site of a collection of curios of the Tradescant father and son. Also buried in this cemetery is Captain Bligh of HMS Bounty who, out of respect and interest in horticultural and botanical matters requested that he be buried in a tomb here.

The Chelsea Physic Garden is the second oldest physic garden in England, established as the Apothecaries’ Garden of London in 1673. Hans Sloane in 1713 had purchased an additional 4 acres (1.6 ha) from the adjacent Manor of Chelsea owned by Charles Cheyne, the additional land leased in 1722 to the Society of Apothecaries. Hans Sloane was a prominent and wealthy diletantte who had known the famous scientists John Ray and Robert Boyle. As a young man he had studied in France with Tournefort and Magnol. When Isaac Newton died in 1727 he was appointed President of the Royal Society. He leased the new land to the Apothecaries for £5 a year in perpetuity on the condition that the Garden supply the Royal Society with at least 50 herbarium specimens a year up to the total of 2,000 plants. Sloane’s natural history specimens would later form the foundation collections of the British Museum.

Miller began work at the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1722 and held this position for 48 years. The garden he inherited had been founded in 1673, more than one and a half centuries before London had a university.[16][3]

Miller’s objective was to build up the garden with novelties and new introductions from wherever they could be obtained. Among his sources were three physic gardens in Edinburgh, at Holyrood, Trinity House, and the university and perhaps his later plant inventories were prompted by the widely-acclaimed Hortus Medicus Edinburgensis (Edinburgh Medicinal Garden) written by its head gardener James Sutherland in 1683.[29] In his day, before the sudden interest in plants from New Holland, it was American plants that were all the rage and Miller was a great importer with friend Peter Collinson (1694–1768), obtaining his plants from their major source in Philadelphia, America, the quaker John Bartram. From Bartram (Collinson sponsored several of his collecting trips) came about 2,000 new introductions including species of Phlox, Ceanothus, Helianthus, Abies balsamea, and the magnificant evergreen magnolia Magnolia grandiflora.[14] From Virginia there was Britain’s first magnolia, M. virginiana sent by John Banister.[20] and from China the majestic Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima. Overall the numbers of new plants soon eclipsed those of the Oxford Physic Garden (est. 1632) and Edinburgh Botanic Garden (est. 1670) as, during the period from 1730 to 1770, he increased the number of species in the collections from about 1,000 to 5,000.[15]. In London Collinson built up his world-wide private garden collection first at Peckham and later at Mill Hill sending out seed every year (notably those collected by Bartram), to British gentry, nurserymen, and natural scientists including not only Miller but Dillenius, Lord Petre, the Dukes of Richmond and Norfolk, James Gordon, and John Busch.[31]

In 1732 cotton seed sent from the Chelsea Physic Garden to James Oglethorpe in the American colony of Georgia served as the basis for a new cotton industry.

In 1986 the four-acre Chelsea garden contained 4500 species laid out in natural order beds based on the system of Bentham and Hooker.[27]

Visit to Holland

At the time of Miller’s appointment Holland was Europe’s pre-eminent horticultural nation with the Hortus Botanicus Leiden a hub. Politically powerful, Holland had superior technology and was benefitting from the activities of the Dutch East India Company whose trading empire reached into countries of the Pacific Ocean.

In 1680 one of Miller’s predecessors, merchant apothecary John Watts, was appointed along with two gardeners with instructions to grow both native and exotic plants. Responding quickly Watts sent gardener John Harlow to collect plants in Virginia. Then in 1682 the Chelsea garden was visited by Paul Hermann, Professor of botany at the University of Leiden, who suggested Watt visit Leiden to establish a plant exchange between th etwo institutions. Watt’s subsequent visit in 1683 initiated not only an exchange of seed and plants between Chelsea and Leiden but the tradition of seed exchange that would become known as ‘the international botanic gardens seed exchange’ which persists to this day.[12] Historically this was the main means of plant aquisition in botanic gardens through the exchange of seed catalogues (Index Semina) and a major means of global plant distribution. In 1685 the famous diarist John Evelyn wrote about the heated glasshouse (one of the few in Europe at this time) and a meeting with Keeper Watts, writing in his diary: ‘what was very ingenious was the subterraneous heat, conveyed by a stove under the conservatory, all vaulted with brick, so as he has the doores and windowes open in the hardest frosts, secluding only the snow‘.[32]

When Miller travelled to Holland in 1727 it was a thriving commercial centre, home to some of the greatest botanical collections in the world and with a reputation for horticultural innovation. At Leiden Miller met Herman Boerhaave, successor to Paul Hermann, one of Europe’s pre-eminent physician-botanist professors and Director of the famous Hortus Botanicus Leiden, one of Europe’s founding botanic gardens. In 1590 a hortus academicus had been constructed behind the Leiden Academy as a demonstration garden for the medical students. The famous botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609) was appointed Prefect and took up his position in 1593. Under his guidance and some influence with the Dutch East India Company the garden built up a collection of more than 1000 different plants. Of special note was the cultivation of tropical plants in greenhouses that had been constructed in the latter part of the 17th century, one of many successes being the cultivation of pineapples.

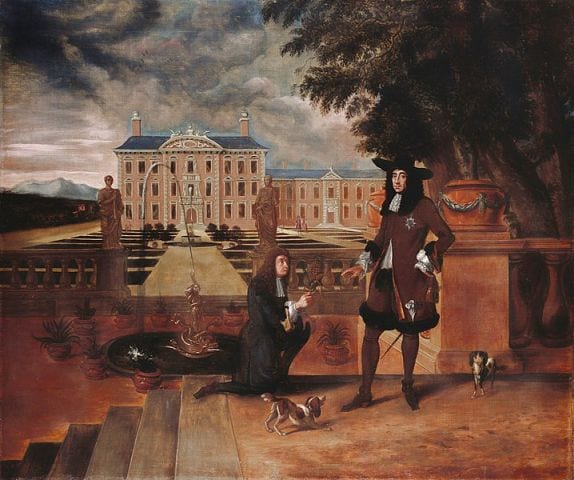

The pineapple was known as ‘the fruit of kings’ in reference to the crown-like topknot of leaves. One was sent to England’s Charles II (1630–1685) in 1661 by a consortium of Barbados planters and merchants hoping to obtain a minimum price for their primary export, sugar. The first pineapple grown to maturity in England from plants imported from the West Indies was presented to Charles II in 1675 by his royal gardener John Rose (1619–1677).

England’s first pineapple grown to maturity and being presented to Charles II of England by Royal Gardener John Rose in 1675

Painted 1787 by Thomas Stewart (1766–c. 1801), after Hendrick Danckerts (1625-1680)

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Royal Collection – Accessed 28 August 2018

Miller arrived in Holland as a student anxious to learn. While in Leiden Miller marvelled at the number and variety of plants in the Leiden collections and was envious of the impressive greenhouse displays. King William III of England, a Dutchman, and his wife Mary had assumed a co-regency of Britain that lasted from 1689 to 1694 and they had been disappointed with the standard of horticulture in England compared to that in Holland. Consequently the hothouse, originally developed in Holland, was introduced to England in 1690 and the first one was installed by William and Mary at Hampton Court.[4]

Returning to Chelsea Miller’s vision was clear: he was determined to increase the London collections and manage them to the highest possible horticultural standards. By the 1730s the Chelsea Physic Garden could boast a collection of plants that would rival any in Europe. In defiance of instructions to not release any of his plants to ‘outsiders’ Miller freely exchanged plants with gardeners both in Britain and overseas amassing rare and curious plants which he grew using the latest horticultural techniques. Two hothouses were designed and constructed incorporating English modifications to Dutch designs (one ‘stove’ and one ‘hotbed’) and a greenhouse and frames were also added.[5]

Plant hunting & introduction of new plants

Inspired by the living collections at the Leiden Botanic Garden (many of its plants brought back to Holland by the Dutch East India Company) Miller began cultivating plant hunters as well as plants. Miller made sure that they were all Scotsmen, often raised on aristocratic Scottish estates and mansion houses which demanded high literacy and plantsmanship.[27] Linnaeus, who paid an admiring visit to Miller’s Chelsea Physic Garden, also had a team of ‘apostles’ who set out on Swedish merchant ships looking for botanical booty. Between 1731 and 1768 [16][17] the number of species cultivated in England doubled. It was Miller and Linnaeus who no doubt, in turn, inspired Banks at Kew and Thouin of the Jardin des Plants to train teams of plant collectors for Enlightenment voyages of scientific exploration. Plants were now being actively hunted rather than incidentally acquired.

Much later, in 1846, Scottish Plant hunter, Robert Fortune would become curator until 1848, among his persisting introductions being ‘Fortune’s Pond’. Fortune was followed by botanist Thomas Moore who, as curator from 1848 to 1887 ensured that Chelsea was the foremost collection of medicinal plants in Britain.

Horticultural innovation

Another horticultural technique introduced from Holland by William and Mary was the use of tanners bark as a soil additive. When incorporated in the soil it would break down extremely slowly raising the soil temperature in what was termed a ‘hotbed’ or ‘tan pit’ which permitted the cultivation in greenhouses of plants from warm climates. In no time Miller had established a collection of West Indian tropical plants using the ‘hotbed’ technique and had also set up a ‘dry stove’ glasshouse with hot air flues along the walls. Innovations like these allowed him to experiment with the cultivation of coconuts and pawpaw, growing tulips and narcissi in bottles of water and other challenging material. An acute observer, he noticed the pollinating activity of bees and that, when absent from the greenhouses, some plants did not set seed this being, for his day, an extremely astute observation on the role of insects in pollination.[6] It was also Miller also who introduced long-strand variety of cotton seeds to the cotton plantations in the British colony of Georgia in America.[7]

Chelsea Physic Garden, Europe’s most comprehensive collection of plants

In 1732 begging letters arrived from Boerhave himself requesting trees and shrubs from the Chelsea Physic Garden. ‘I know of no one in your country who is more capable to identify and distinguish them’ and … ‘Remember, I beg you, my garden’.[8] This was an acknowledgement by Boerhave of Miller’s achievements and a virtiual acknowledgement of the transition of European horticultural pre-eminence from Holland to Britain.

Influential friend, the English plant merchant and quaker draper Peter Collinson who was himself a notable plantsman recorded in 1764 that Miller ‘has raised the reputation of the Chelsea Physic Garden so much that it excels all the gardens of Europe for its amazing variety of plants of all orders and classes and from all climates …’[10] Collinson was a Fellow of the Royal Society, an enthusiastic gardener, and one of London’s mid-18th century scientific intellectuals, well known for his American connection to John Bartram and correspondence with Benjamin Franklin in America.

Private herbarium specimens and illustrations made in the period of Miller’s curatorship still exist which is most important as he described many new species. These collections are now housed at the Natural History Museum, many serving as voucher specimens for plants cultivated in Britain for the first time.[14] His private herbarium was purchased in 1774 by Joseph Banks three years after Miller’s death and subsequently passed at Banks’s request to the Botany Department of the British Museum of Natural History. A further official collection made specifically from specimens growing in the Chelsea Physic Garden and is also housed in the Museum assembled as ’50 specimens a year’ as demanded by Hans Sloane ‘… until the compleat number of two thousand plants shall have been delivered’. This was duly achieved and the results published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[22] Three hundred copper-plate coloured engravings of Chelsea Physic Garden plants were prepared by artists of the day and are an excellent record including those of Georg Ehret (1708-1770) who married Miller’s sister-in-law in 1708.[23]

The Gardener’s Dictionary

The problem of plant names

As new plants poured into the country, keeping track of their names became virtually impossible, a situation made worse by Miller’s refusal to accept the Linnaean binomial system. Dissatisfaction with plant naming in nurseries had been an issue for some time. A Society of Gardeners was set up in 1725. Made up of about 20 prominent horticulturists it was established to put an end to the confusion, but it was soon disbanded although some of the work they did in ‘registering’ the names of newly introduced plants, the Catalogus Plantarum (1730), was no doubt used by the society’s clerk, Miller, in his Dictionary.[11]

Britain’s Species Plantarum

Linnaeus, who visited the Chelsea Physic Garden on three occasions during his visit to England in 1736 described Miller as ‘Hortulanorum Princeps’ (Prince of gardeners) and Miller’s Dictionary as ‘Non erit Lexicon Hortulanorum sed etiam Botanicorum’ (not just a dictionary of horticulture but a dictionary of botany too).[9] Botanical historian Kurt Sprengel in his Historia Rei Herbariae (1808) awarded him ‘superlative upon superlative’[21] Modern botanical historian William Stearn described the Gardeners Dictionary as ‘the most important horticultural work of the eighteenth century’, especially the 8th edition using Linnaean binomial nomenclature which was published on 14 April 1768.[21] Each edition had marked the process of plant introduction through the century and giving us much-needed approximate dates of introduction as well as invaluable historical and botanical information.

Much of Miller’s reputation today stems from two monumental horticultural publications: The Gardener’s and Florists Dictionary or a Complete System of Horticulture (1724) and The Gardener’s Dictionary containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen Fruit and Flower Garden (1731) dedicated to Hans Sloane.[19] This was, in effect, Britain’s Species Plantarum, a compendium of virtually all the plants known to the British at that time some 30 years before Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735) and Species Plantarum (1753) while it also included general horticultural and botanical advice along with the alphabetical listing of names.

The Dictionary remained a definitive work for over a century, running to eight editions in his lifetime (between 1731 and 1768) and 16 editions by 1830, each edition elaborating on its predecessor and eventually appearing in Dutch, French, and German translation.[30] It was the precursor, through a long line of encyclopaedias and dictionaries produced over the years by the Royal Horticultural Society, to today’s authoritative four-volume The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening (1992) and the RHS Plant Finder 2018-2019, a present-day list of plants available in the British nursery industry which contains over 70,000 different plants.

William Stearn’s Historical Introduction to the New RHS Dictionary . . . points out that in 1807 Thomas Martyn (1756-1825) produced a much-enlarged 4-vol. edition called The Gardener’s and Botanist’s Dictionary dedicated to Joseph Banks. Thee should, here, also be mention of John Caudius Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Plants with three editions published between 1829 and 1855 with most of the first edition the work of John Lindley, and his Hortus Britannicus of which three editions appeared from 1830 to 1839, and George Johnson’s Cottage Gardener’s Dictionary whose last edition appeared in 1917. Considered deficient an erudite 20-year-old William Roberts (1862-1940) for t40 years from 1882 to 1884 undertook an update, leaving his work with London publisher Upcott Gill. It was then the turn of Kew’s garden Curator George Nicholson to revise and expanded Roberts work to produce The Illustrated Dictionary of Gardening published in several parts between 1884 and 1888. Though a monumental work the Illustrated Dictionary . . . was soon outdated because of the numerous plants introduced from China between 1900 and 1914. In America the outstanding horticultural botanist Liberty Hyde Bailey (1858-1954) of Cornell University together with a team of horticultural writers produced between 1914 and 1917 the high-standard Cyclopaedia of Horticulture. By 1936 in Britain a new encyclopaedia was clearly needed and the RHS initiated what became known as ‘Chittenden’s’ named after the Director of the RHS Society Garden at Wisley. This was published in 1951 as the 4-volume Dictionary of Gardening, the work of 43 contributors. Then by 1987 work had begun on the New Dictionary . . . which was published in five volumes in 1992. This publication can be regarded as among the first to count as a global flora of cultivated plants.

As a definitive work Miller’s Dictionary was also a product of the Enlightenment desire to synthesize scientific knowledge into accessible encyclopaedic compendia of knowledge. Other publications by Miller include: A Catalogue of Trees Near London (1730), A Gardener’s Kalendar (1732). In 1735 he released an abridged edition of the Dictionary costing a few shillings, putting the book within reach of virtually everyone.

Miller resisted Linnaean binomial nomenclature and preferred the classification systems of Frenchman Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1678) and Englishman John Ray (1627-1705). He remembered with pleasure, as a young man, meeting John Ray and this may have been why he only eventually deferred to the Linnaean system in the eighth (1768) edition.

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

Miller’s encyclopaedic knowledge of plants was legendary: his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society acknowledging the momentous achievement of his Dictionary. From the Chelsea Physic Garden his influence spread through his trainees that included William Aiton, Head Gardener at Kew, the famous proprietor of the Gardener’s Magazine, William Curtis and Miller’s own successor William Forsyth Snr,[33] another Scotsman who added to Miller’s collections before becoming gardener to George III at Kensington and St James in 1784.[12] As his reputation grew he was commissioned by the gentry, such as the Duke of Bedford, to advise on garden design and the latest horticultural practice.

As Head Gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden Miller witnessed the final stages of the emergence of modern botany and horticulture from its foundations in medicine overseeeing the transition from an apothecary’s physic garden of ‘simples’ or ‘officinals’ to collections of ornamental and economic plants as part of a revolution in in horticulture and the role of botanic gardens and medicine, botany and horticulture redefined their place in the world. Historically this was a time of British, Dutch and French colonial expansion and the beginnings of what would shortly become a keen plant exchange between the Paris, Leiden and Chelsea and other gardens.[21] Influential botanists and horticulturists throughout Europe acknowledged the Chelsea Physic Garden as a hub for their interests at a time when Kew was a relatively insignificant royal estate established as Princess Augusta’s Physic Garden by William Aiton (who trained under Miller between 1754 and 1758). Miller’s influence was not unlike that of Joseph Banks and Carl Linnaeus though within the realm of horticulture. Miller transformed the Chelsea Physic Garden into what was possibly Europe’s most extensive plant collection well before Banks’s Kew Gardens took over this role. In the period between 1731 and 1768 the number of species cultivated in England doubled as plants came in from North America, the Cape of South Africa, Siberia, and the East and West Indies[17] in an era of plant collecting that preceded the next phase of plant hunting that would occur in Australia and China. Under Miller the:

‘ . . . Chelsea Physic Garden became the most famous botanic garden in eighteenth century Europe.[18]

Miller had a reputation for combining an interest in both botany and horticulture and under his curatorship from 1722 to 1770 the garden enjoying a golden age as plants poured into it from around the world and Chelsea became the most richly stocked botanic garden in the world. The newly-introduced plants were beautifully illustrated by the botanical artist Georg Ehret (1708–1770) in Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary. Ehret was arguably the greatest botanical artist of the day, and set a high standard for the future botanical illustrators who would make their mark working on plants collected on the great Enlightenment voyages of scientific discovery around the world.

Millers books mark a time in England’s social history when gardening was becoming more inclusive, extending from the estates of the wealthy to other strata of British society. His books were a means of empowering these people, passing on invaluable information to not only the professional estate managers but amateur plant and garden lovers. In the Enlightenment tradition this was also a highly practical book based on observations of what actually ‘worked’ in the garden written in a simple and direct style so unlike the florid prose and superior ponderous and pedantic tone adopted in so much literature of his era.

Sadly in 1771 Miller died in the same year that Banks and Solander returned to England from Cook’s first voyage of scientific discovery, the Endeavour laden with an impressive haul of plants from the newly charted east coast of New Holland, plants that Miller would dearly have loved to see. His memory and significance has probably been overshadowed, firstly, by the glamour of the discoveries of the plants themselves which diverted attention from his momentous horticultural achievements and, secondly, by his curmudgeonly resistance to the Linnaean system of plant classification and nomenclature which resulted in his dismissal from his job in 1770 due to a certain:

‘imbecility and peevishness consequent upon his great age’.[13]

Miller, through his many new plant introductions, voluminous correspondence which included people like John Bartram in America, together with a wide and illustrious number of British and international leading figures in the history of natural science including Hans Sloane, Carl Linnaeus, John Ray, Joseph Banks, Peter Collinson, Herman Boerhave, Richard Warner and many more. He was a stimulus to Banks and the Botanophilia that would later grip Europe and laid down much of the culture of present-day botanic gardens with their herbaria, plant catalogues, seed and plant exchange, quality horticulture, botanical illustration and love of botany.

As a member of the Royal Society he was a key figure in the foundation of the ethos of Western horticulture at a time when Chelsea, not Kew, was the pre-eminent garden in England. His biographer Helen Le Rougetel describes him as:

‘ . . . the most distinguished and influential British gardener of the eighteenth century, esteemed not only in the British Isles but throughout Europe and the British colonies in America for his practical skill in horticulture and his wide botanical knowledge of cultivated plants‘.

As a towering figure of eighteenth century horticulture his legacy, the ethos of plant collection from distant lands, and the horticultural practices of Britain that he symbolised would also pass to Australia and the later British empire. In this way he can also be seen as a founding father of the Neo-European-cum-English horticulture that has been inherited by the world.

No portrait exists of Philip Miller, the one commonly used being of botanical artist John Miller.[13]

During a long period from 1780–1814 it was Head Gardener and Curator John Fairbairn who continued the tradition of plant collection and who maintained contact with Banks at Kew.

Timeline

1632 – Foundation of the Oxford Physic Garden

1670 – Foundation of the Edinburgh Botanic Garden

1673 – Foundation of The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries (The Chelsea Physic Garden)

1682 – An international seed and plant exchange established after the garden was visited by Dutch Professor of Botany at Leiden University, Paul Hermann. Production of seed catalogues (Index Semina) was to later become a major means of plant exchange and aquisition through the world’s network of botanic gardens

1683 – Hortus Medicus Edinburgensis published by its Head Gardener of the Edinburgh Medicinal Garden, James Sutherland

1685 – Visit by diarist John Evelyn who records a meeting with Keeper Watts and the presence of a heated glasshouse (one of the few in Europe at this time)

1690 – The hothouse, developed in Holland, was introduced to England’s Hampton Court from Holland by William and Mary, enabling the cultivation of tropical plants

1721 – Observes the transfer by insects of pollen between flowers

1723-1770 – Curator Chelsea Physic Garden

1723 – Starting work at the Chelsea Physic Garden (est. 1673) in 1722 he is appointed Head Gardener in 1723

1724 – Publication of The Gardener’s and Florists Dictionary or a Complete System of Horticulture

1725 – Formation of the Society of Gardeners set up to remedy confusion over plant names

1727 – Visits the Leiden Botanic Garden where the eminent Hermann Boerhave was Director and also Professor of Botany at the Leiden University

1730 – Catalogus Plantarum, list of names produced by the Society of Gardeners, mainly the work of Miller

1730-1770 Increases the number of cultivated species from about 1000 to 5000

1731 – Publication of The Gardener’s Dictionary containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen Fruit and Flower Garden

1732 – Requests from Boerhaave for plants from Chelsea

1736 – Linnaeus makes three visits to the Chelsea Physic Garden showering Miller with praise but the difficult pair do not get along

1754-1758 – Supervises William Aiton, subsequent Head Gardener at Kew

1760s – Banks becomes a regular visitor to the garden, Miller instilling in Banks an enthusiasm for plant collection

1764 – Nurseryman Peter Collinson declares Chelsea Physic Garden the best garden in Europe

1768 – Eighth edition of the Dictionary published, this time using Linnaean classification

1774 – Miller’s private herbarium purchased by Joseph Banks eventually passing to the British Museum of Natural History

1826 – Forsyth Jr publishes History of English Gardening under the name George William Johnson – the first history of English gardening

Key points

- In 1723 when Miller was appointed Head Gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden the Hortus Botanicus Leiden was recognised as a European centre for botany and horticulture

- In the period 1731 to 1768 the number of species cultivated in England doubled as plants poured in from North America, the Cape of South Africa, Siberia, and the East and West Indies. By 1768 Chelsea could boast the most extensive plant collection in Europe

- Horticultural innovations included the importation of the hothouse from Holland by William and Mary, the use of tanners bark as a soil additive in raised ‘hotbeds’ allowing growth of tropical plants, dry stove houses with hot air flues, and introduction of the long-strand cotton variety to the plantations of Georgia in America. He was probably the first person to make the connection between bees and plant pollination

- He was an exemplary and influential Enlightenment figure in European horticulture epitomising horticultural traditions and practices that would become part of botanic garden culture and accepted horticultural practice in Britain, Europe, and later the British Empire and countries that have subsequently fallen under its influence

- The Gardener’s Dictionary if 1731 included general horticultural and botanical advice along with the alphabetical listing of names: it marked the process of plant introduction through the century giving much-needed approximate dates of introduction as well as invaluable historical and botanical information: it would remain a major reference work running to 16 editions by 1830

- The Gardener’s Dictionary if 1731 included general horticultural and botanical advice along with the alphabetical listing of names: it marked the process of plant introduction through the century giving much-needed approximate dates of introduction as well as invaluable historical and botanical information: it would remain a major reference work running to 16 editions by 1830

- The Dictionary was rightly praised by Linnaeus since it was, in effect, Britain’s Species Plantarum, a compendium of virtually all the plants known to the British at that time and preceding not only Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735) but compiled some 20 years before the publication of Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum (1753)

- He resisted the tradition of patronage, dilettante botanists and the perception of botany as a leisurely hobby, doing this by successfully lobbying for state-paid botanists at the British Museum

- Millers books mark a time in England’s social history when gardening was becoming more inclusive, extending from the estates of the wealthy to other strata of British society

- Three hundred copper-plate coloured engravings of Chelsea Physic Garden plants were prepared by artists of the day

- Private herbarium specimens and illustrations made in the period of Miller’s curatorship still exist, many as new species: these collections are now housed at the Natural History Museum serving as voucher specimens for plants cultivated in Britain for the first time

- Many of the plants Miller acquired were first introductions that would eventually find their way into the countries of the British Empire including Australia

- As Head Gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden Miller witnessed the final stages of the emergence of modern botany and horticulture from its foundations in medicine overseeeing Chelsea’s transition from an apothecary’s physic garden of ‘simples’ or ‘officinals’ to collections of ornamental and economic plants as part of a revolution in horticulture and a new role for botanic gardens

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019