Plane tree

Familiar mottled and flaking bark of the London Plane, Platanus x acerifolia

Platanus is the Latinised form of the ancient Greek name for this genus, Platanos, derived from platys – flat or shielding referring to the broad, shady leaves

Image Roger Spencer

Introduction

The plane tree is an arboreal archetype that connects us to our deep physical and psychological past . . . to plant lore and myth and the ancient sacred grove. Its native geographical distribution across Eurasia means that it has featured in the classical literature of both East and West. Among the most ancient of plants its evolution takes us back about 110 million years in geological time.

Theophrastus the ‘Father of Botany’ recalls a giant plane tree with roots extending over 30 cubits[13] growing in the grounds of the Lyceum in ancient Athens where he taught botany at the dawn of plant science.

There are just six or seven species in the plane tree genus Platanus most occurring in SW North America and Mexico with one species in eastern America, one species in eastern Europe and western Asia, and another species in Indo-China. Platanus is a monogeneric relictual genus, that is, it is the sole surviving genus in the family Platanaceae and a representative of a formerly diverse plant group: present-day species occur in both Eastern and Western Hemispheres, trees from these two zones sometimes being inter-fertile.

Only three kinds of plane have been widely cultivated, their botanical names suggesting an entire evolutionary and human narrative: Platanus occidentalis, Platanus orientalis, Platanus x acerifolia – west, east, and a hybrid fusion of the two. The London Plane, which is the quintessential pollution-absorbing shady urban tree, is our most obvious arboreal manifestation of the fusion of Old and New Worlds that occurred as a ‘Columbean Exchange’ during the Age of Discovery and after, as part of the acceleration in cultivated plant globalization.

The hub of most French villages, especially in Provence, Plane trees are symbolic of socialising and spending time with loved ones.

Deep history

The very first fossils of flowering plants (Angiosperms) date back to about 125 million years ago. Plane tree fossils date back to at least the late Albian Age of the Lower Cretaceous geological period about 100-113 million years ago being among the very early fossils of flowering plants.[9]

Ancient Greece

As in all cultures trees were treated in Greece with a great reverence that dated back into prehistory See Plant lore). Ancient Greeks regarded the tree as a divine gift and it features strongly in Greek literature. As early as the 8th century BCE Greek epic poet Homer describes how Greek soldiers performed a sacrifice beneath a plane tree (from which emerged a spring) before the Greek fleet set sail from Aulis for Troy. Physician Hippocrates taught his medical students under a tree on the island of Kos; an island was named Plataniste after its magnificent trees and here Spartan men exercised; virgins of Sparta recognised the plane as a symbol of Helen of Troy and Roman poet Virgil tells us they sang ‘reverence me for I am the tree of Helen‘; when Socrates swore, he swore not by the gods, but by the plane tree. A tree planted by Theophrastus was said to grow at Delphi and a grove of plane trees provided shade for students at the famous Lyceum of the peripatetic philosophers in ancient Athens. Pausanius in 2nd century tells of hollow plane tree trunks where people lived. Theophrastus himself described the wood as tough and valued by cabinet makers because it could be polished. Dioscorides recommended the leaves as treatment for a variety of ailments.[4]

Plane tree of Hippocrates

Alleged stump of plane tree under whose canopy Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BCE) the ‘Father of Medicine’ taught his medical students on the island of Kos

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Herodotus describes the use of plane trees in 1st century Rome while Pliny recalls a hollow specimen in Lycia that housed a dinner party of 18 people. He also reports that king Xerxes, the great Persian military leader, when marching through Asia in preparation for his invasion of Greece c. 480 BCE, set up camp at the Lydian town of Kallatebos before crossing the river Maeander (where men made their living by preparing wheatmeal and preparing honey from tamarisk). Here he observed a magnificent plane-tree, hanging on it golden ornaments and arranging for a permanent guardian before proceeding to Sardis.[7]

Today the Oriental Plane grows naturally in many areas of Greece and is cultivated in churchyards, main squares and along the Banks of streams, still providing locals and tourists with welcome shade around the cafes and tavernas. The largest specimen in Europe is probably one that grows in the village square at Tsangarada on the slopes of Mount Pelion.[12]

Ancient Rome

The first pubic park of Ancient Rome was opened by General Pompey the Great in 55 BC. It consisted of a porticus (colonnade) enclosing a nemus or sacred grove within a temple precinct. For twenty years it proved one of the most popular places in Rome, serving as a precedent for many of the later public parks and it shared many of the lavish and verdant characteristics of the opulent horti owned by wealthy generals on the outskirts of the city. Avenues in the nemus were thickly planted with plane trees that provided shady promenades.[11]

Islamic world

Another indication of the importance of the ÿenÿr in Persia is the large number of localities (mostly hamlets and villages) named with reference to it. There are 28 localities named ÿenÿr, 12 named ÿenÿrÿn (note also ÿenÿrÿn-e Beyglar ÿÿn, a hamlet west of Nehÿvand), 45 toponyms consisting of ÿenÿr and a complement. Among the gardens laid out by Tÿmÿr (Tamerlane) in Samarqand was a plane garden (Bÿÿ-e ÿenÿr) mentioned by Šÿmÿ (p. 211) and Bÿbor (p. 78), the founder of the Mughal empire in India. Bÿbor also mentions the Bÿÿ-e Kalÿn ‘Great garden’ in Kabul, in which garden stout planes were found. Medicinal properties and uses were found out for the plane by Dioscorides (I.107, Eng, tr., p. 58; Ar. tr. apud Ebn al-Bayÿÿr, I, pt. 2, p. 94, s.v . dolb) and Galen (Ar. tr. ibid.). The physicians and pharmacologists of the Islamic world in the Middle Ages have added hardly anything new to the findings of the Greek masters. Marco Polo refers to a lofty, solitary tree in the province of Tonocain (i.e., Tÿn o Qÿÿen), which he calls the tree of the sun (Arbre Sol).[10] A famous old specimen still grows at Ulubat Golu near Bursa in Turkey.

Plane trees in England

After the glories of Greece and Rome it was London more than any other city in Europe that took on the classical mantle. Until recent times London was the largest city in the world after classical Rome with its population probably topping one million at the peak of empire.

Plane trees are first recorded in William Turner’s Herball of 1551 and also mentioned nearly a century later in Parkinson’s I Solo Paradisi of 1640.

Plane trees were certainly commercially available in the London nursery of Thomas Fairchild (1667-1729) who was a member of the prestigious Society of Gardeners, a group of about 10-20 leading horticulturists who would meet at monthly intervals in Newhall’s coffee House in Chelsea. England was on a horticultural high as, on the cusp of a grand empire that would encompass about 25% of the world population when Britain ‘ruled the waves’, harvested the world for new plants and, in keeping with an ascendant world power was about to launch on Europe the now famous English landscape style of estate gardening. The Society probably met in Chelsea because their clerk was Philip Miller, curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden, arguably at its peak Europe’s foremost collection of living plants and precursor to today’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Miller published the Gardener’s Dictionary, which ran to many editions and probably counts as the most important horticultural book of the eighteenth century. Fairchild too is assured a place in horticultural history, not so much for his introduction of the plane but because he was the first horticulturist to carry out an intentional hybrid cross – between the carnations Dianthus caryophyllus and D. barbatus which resulted in a garden selection that became known as Fairchild’s Mule.

In 1920 it was estimated that more than 60% of London trees were planes.[6]

Oriental Plane

Oriental Plane

Platanus orientalis

Native to Greece (including Crete) and bordering Bulgaria, Macedonia and Albania it is often listed as growing naturally in the southern Balkans, the mountains of S.Turkey, W. Syria, N. Iraq and Iran, eastwards to Kashmir. Being widely naturalised from ancient times we will probably never know its true natural distribution. In its eastern range it is known as as Chenar (or some spelling variation of this)

Following classical tradition, its proven hardiness and pedigree was assured when influential diarist and arbiter of taste John Evelyn (1620-1706) suggested that planes might be used ‘ … to the incredible ornament of the walks and avenues to great men’s houses’. Native to the region between Italy and the Balkans Oriental Plane has, since antiquity, been planted well beyond its native range. So the plane was introduced to London as a street tree. The origins of the hybrid tree and the specific clone now known as the London Plane are shrouded in horticultural, botanical, and nomenclatural uncertainty. Garden historian Miles Hadfield traces the first reliable record of Oriental Plane in Britain to William Turner’s Herball written (but not published) in 1548 and he mentions a living tree in Weston Park Stafford that was probably planted in 1757. Although it would grow in the cooler north of England the best specimens occurred in the south-east.[1]

Perhaps the most famous public meeting place in the ancient world was the market place in the centre of ancient Athens, the Agora, famously planted with plane trees and we see its echo in the plane trees of London’s Hyde Park and again in the old plane trees of Hyde Park in Sydney. Some planes in the City of London Cemetery are estimated to be more than 300 years old the Osterley Park Oriental Plane allegedly dates back to 1755 and another in Kew Gardens to the 1760s while the ?London plane at Barn Elms, London SW13, is probably from about 1685, planted on lands then belonging to the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is London’s oldest and largest plane. Bean suggests that, in spite of references to its British introduction ‘before 1548’, a more likely date of introduction to Britain was in the late 16th century following the establishment of the Levant Company.

Trees can grow to about 30 m tall and, apart from the deeply cut lobes on the leaves, are recognised by the fruit ‘bobbles’ that are mostly in groups of 2-5. Old trees develop massive squat boles that, when hollowed out have sometimes served as a temporary lodging.

The oldest oriental plane at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew in London was probably planted at the time of princess Augusta in 1792.[12]

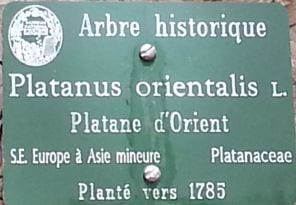

Label of old Oriental Plane Tree, Platanus orientalis, in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris

Tree planted in 1785.

Photo: Roger Spencer – 23 June 2014

In the eastern range of its natural distribution it is known under its Persian name of Chenar (Chinar).

Cretan Plane

An evergreen variant, P. orientalis var. cretica[8], grows on the island of Crete. A fine ancient specimen can be seen today at the archeological site of Gortyna, a location cited by Theophrastus. Greek mythology recounts the story of beautiful Phoenician princess Europa abducted by the god Zeus who seduced her under a plane tree, attracting her by assuming the form of a magnificent white bull. To commemorate the seduction, which took place in the shade of a plane tree, Zeus transformed the local tree into an evergreen. This legend of Europa and Zeus was popular during the Renaissance and a favourite theme of 18th century painters. This evergreen plane features as a leaf next to the nymph Europa (origin of the word Europe) and a white bull on the obverse side of a present-day commemorative 2 Euro coin.

Western Plane

All authorities agree that the first English mention of the North American Western Plane (P. occidentalis) occurs in Thomas Johnson’s edition of Gerard’s Herball (1631) with John Tradescant having two small plants also a record by Jacob Bobart (1599-1680) for the Oxford Botanic garden but all early specimens, it appears, could not survive British conditions to achieve maturity, early records of adult trees in usually reliable sources, as in Evelyn’s Sylva (1776) and Loudon’s Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838), referring no doubt to the London Plane.

Lopped planes in the public garden (est. 1865) at the centre of Porto, Portugal

Photo: David Wixted

Western Plane (also known as American Plane, Buttonwood, Buttonball, or Whitewood) is the largest-growing of the plane species, some trees attaining a height of 50 m, its best character of recognition being the single dangling fruit ‘bobbles’. Identification in America especially has been complicated by the hybrids that, when taken to America from Europe, have backcrossed with this species to produce a puzzling degree of variation.

Common (London) Plane

John Bobart was Superintendent of the Oxford Physic Garden, one of England’s first botanic gardens constructed during the Renaissance. In a catalogue of his stock compiled in about 1666 Bobart lists ‘Platanus inter orientalum et occidentalum media’ (a plane with characters between the east and west species) and two herbarium specimens with such characters exists in the Sherardian Herbarium at Oxford University, later described in full in about 1700 by Leonard Plukenet (1641–1706) Royal Professor of Botany at Oxford, and gardener to Queen Mary. Since Western Plane has not been grown to maturity there has been long debate about the true origin of the hybrid, a mystery as Oriental Plane was a late introduction to America and France did not have Oriental Plane until the early 18th century.[5] Vague references were made to Spanish Plane in the early literature and a garden varity ‘Hispanica’ has also suggested a possible Spanish or Portuguese origin. Miller had himself described a tree in his 1759 Gardener’s Dictionary which he referred to as the Spanish Plane and which was subsequently given the formal botanical name Platanus x hispanica as an acknowledgement of its probably hybrid origin, but no Miller specimens remain.[2]

British tree authority Bean expresses th e difficulty as follows:

‘Having at first taken the view that the London plane was a seedling variant of P. orientalis that became fixed by cultivation, Dr Henry (Augustine Henry,1857-1930) later came to accept that it was of hybrid origin, and in his paper ‘The History of the London Plane’ he attempted to show that it had originated in the Botanic Garden at Oxford around 1670. This paper, written in collaboration with Margaret Flood, was published in 1919 in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 35 (B), pp. 9-28, and its main conclusions are summarised in Gard. Chron., Vol. 66 (1919), p. 47. The Oxford tree, catalogued by the younger Bobart as Platanus inter orientalem et occidentalem media, is represented by two herbarium specimens dating from the latter part of the 17th century, which Henry identified with the London plane. One of the weaknesses of his argument is the absence of any proof that the tree originated at Oxford. If P. acerifolia is a hybrid between the oriental and western planes it is likely that the cross occurred – very probably more than once – somewhere in southern Europe, and that the Oxford tree, or the seed from which it was raised, came from a botanic garden in that region. But it should be remarked that, judging from one of the two herbarium specimens cited by Henry, it is questionable whether the Oxford tree was P. acerifolia and not some form of P. occidentalis.’

Bean adds later that British nurserymen, finding P. orientalis hard to propagate, imported seed from France which was in fact P. acerifolia – often grown on the continent as P. orientalis. According to him, the seedlings from these importations resembled the London plane but had more deeply cut leaves (Gard. Chron. (1866), p. 316). Also, that in 1770, Muenchhausen had given the name P. hispanica to the plane that Miller had first described in the 1759 edition of his Dictionary.

The presence of many slight leaf variants has given rise to a number of named clones but certainty of identification probably awaits a genetic procedure as even the London Plane clone itself is disputed. One difficulty is that some variants of the Oriental Plane have leaves closely resembling those of the hybrid – like those of ‘The Tree of Hippocrates’ on the island of Kos in the Greek Dodecanese islands.

It is the hybrid that is today promoted for its hardiness, vigour, ability to survive in cramped root space, poor soils, ease of propagation, amenability to heavy pruning and its tolerance of vandalism, neglect and the polluted atmosphere of cities. As always the shade in summer and openness in winter provide welcome variety.

As expected the London Plane shares the characters of its parents, the bristly ‘bobbles’ mostly in pairs. The twigs have a distinctive zig-zag form. Occasional specimens with variegated leaves may be encountered.

The English National Trust holds a National Collection of Platanus at Mottisfont Abbey in Hampshire and other significant collections held at botanic gardens, notably the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew and The Hillier Arboretum in Hampshire.

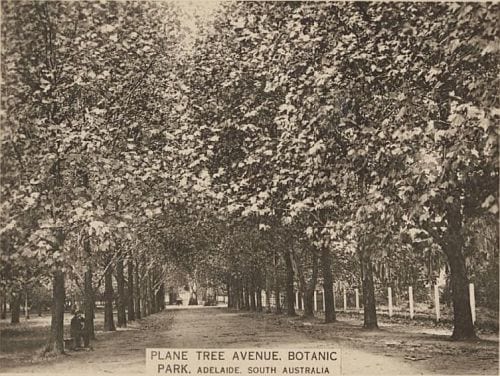

Australia

As in Britain the plane tree is one of the most popular street trees. Most southern Australian cities have avenues of Plane Trees lining many of their streets, providing welcome seasonal change to many suburbs and inner city areas. London plane is listed for Handasyde McMillan & Co., Elizabeth St Melbourne in 1864 and Lang’s Nurseries in Ballarat and Melbourne y in 1865. By the 1870s planes were widely available. Trees were grown from seed obtained from the hybrid London Plane resulting in specimens with considerable leaf variation. Seed stock of Oriental Plane was obtained from Cyprus by Professor Lindsay Pryor (influential in the planning of the street trees of Canberra from its early days) in 1955 and it seems seed of this stock has resulted in a degree of leaf variation. Since Oriental Plane shows some resistance to the new fungal anthracnose, Apiognomonia veneta, and has a degree of attractive autumn colouring it is now the favoured tree for street plantings in many areas.

Like other planes this tree tolerates pollution, neglect, vandalism and poor soils while generously providing plenty of summer shade and in winter a deciduous canopy that allows the sun through painting its tracery shadows on the pavements and roads: somehow it seems made to fit in with city architecture.

First records of Platanus available commercially in Victoria are of P. orientalis from Handasyde McMillan Nursery in 1864 and elsewhere in 1865. Trees are prone to Powdery Mildew, Microsphaera ulni, and the more serious Plane Anthracnose Apiognomoia veneta which attacks the new buds.

P. orientalis has the cultivars ‘Autumn Glory’ from Duncan and Davies in New Zealand, first listed in 1973 and selected for its long-held golden autumn foliage. P. x acerifolia is often grown as the USDA cultivars ‘Columbia’ and ‘Liberty’ which have strong branches and resistance to Plane Anthracnose.

In October 2019, after a spate of allergic and respiratory complaints, the Melbourne City Council, in a break from Western urban tree-planting tradition dating back to at least the Greco-Roman cities, announced a policy for the progressive removal of plane trees from the city precincts.

W.D. & H.O. Wills Cigarette Card published 1925

Trove PIC/5324 LOC Album 1006

Adelaide (Adelaide Botanic Garden; Frome Rd, old plantings of London and Oriental Planes); Unley Park (old plantings of London and Oriental Planes).

New South Wales:

Bowral (Corbett Gardens); Goulburn (Court House); Orange (Cook Park; Robertson Park); Ournie (Jephcott Arboretum near riverbank, 5 m circumference at chest height, 34 m tall, spread 35 m in 1991); Sydney (Centennial Park; Hyde Park; Redfern Park; Royal Botanic Garden Sydney); Wagga Wagga (widely used street tree); Wellington (Park).

Victoria:

Coburg (De Chene Res.); Hawthorn (Central Gardens); Melbourne (St Kilda Rd & rear garden of Melbourne Club, Collins Street); Leongatha (Moss Vale Park); Murchison (Gregory’s Bridge Hotel); Malvern (Malvern Gardens, High Street); Kew (avenue Sackville St); Melbourne (Treasury Gardens); Parkville (courtyard of 1888 Building – formerly Melbourne University Teachers College); Walhalla (back of old Bank vault).

Tasmania:

Hobart (Salamanca Place, Castray Esplanade, exceptional avenue of trees over 100 years old); Launceston (Brickfields Reserve; Cataract Gorge Reserve; City Park).

Source: Spencer, R. (1997). Platanaceae. In: Spencer, R.. Horticultural Flora of South-eastern Australia. Volume 2. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Part 1. The identification of garden and cultivated plants. University of New South Wales Press.

Allergies, pollen & hair

As every arborist knows, there is no such thing as a perfect street tree.

Common Plane

Platanus x acerifolia

Sharp hair (silica spicules) shed from the fruit capsule ‘bobbles’ here gathering in a street gutter

From the earliest times pollen and hair coming mostly from the flowers and fruit capsules, but also the slough of hair that comes from young leaf surfaces, has been associated with headaches, migraines, ‘temperatures’, eye irritation and assorted allergic reactions, some extremely similar to the common cold with running nose, streaming eyes, itching and sneezing. The fruit is a ball of 1-seeded nutlets. When mature each nutlet is shed with a basal tuft of hair. Spring is the pollen season and in Sydney the height of pollen production in the London Plane occurs in September and high levels can be measured in the atmosphere, some people suffering an allergic reaction called pollinosis sometimes associated with food allergies as an immune system activated by plane pollen will recognise similar plant proteins in foodstuffs as occurs in hazelnuts and celery.[3]

Commentary

The plane tree is a cultural icon. Among the earliest references to the plane (though identification is always a challenge for ancient documents). There is a reference to it in the bible – Genesis 30: 37 and Ezekiel 31: 8.

Evergreen Cretan Plane

A 2-Euro coin whose image depicts a scene from a mosaic in Sparta of the third century CE with Zeus (in the form of a white bull) falling in love with and abducting the voluptuous Europa, a Phoenicean princess who he observed picking flowers. Transporting her to the island of Crete he seduced her in the shade of a plane tree, the tree later made evergreen by Zeus to commemorate the event. Evergreen plane trees are of limited distribution. Then, revealing his true identity Europa became the first queen of Crete. Europa’s name became that of the continent of Europe, which is called Europa in all Germanic languages (except English), and in all Slavic languages which use the Latin alphabet, as well as in Greek and Latin. Coin diam – 25.75 mm, thickness 2.2 mm, wt – 8.5 gr. A bimetallic alloy, the ring Cupronickel (75% copper – 25% nickel clad on nickel core), centre Nickel brass (75% copper – 20% zinc – 5% nickel). Edge lettering (Hellenic Republic). Designer G. Stamatopoulos. Minted in Suomi (Finland) as indicated by letter ‘S’ in basal star. 70,000,000 minted. KM#188 – VF – $10