Plant domestication

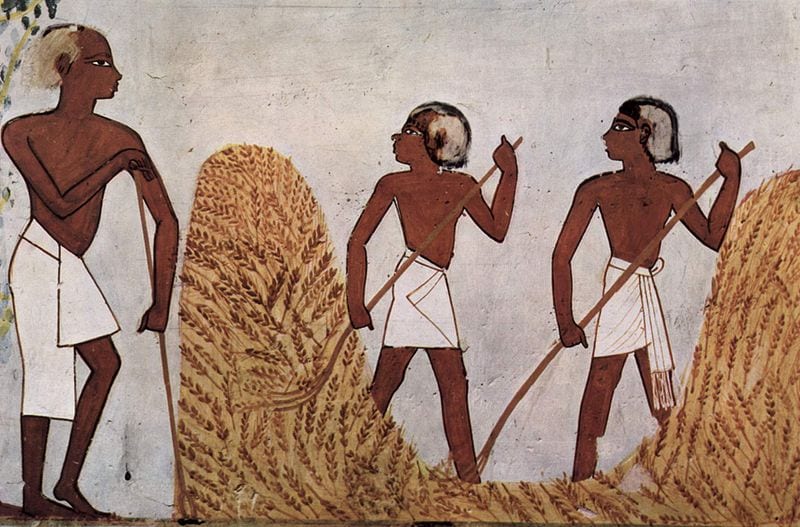

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

There have been two major human historical influences on the plants of the world: their genetics (see plant domestication and man-made plants), and distribution under cultivation (see plant cultivation, and cultivated plant globalization).

Introduction – Plant Domestication

Domesticated plants may be categorized in various ways. The four first-order categories used here relate to groups of plants that belong to different spheres of human activity. There are two major groups associated with food and drink groups. Firstly, there are the temperate (mostly cereal) agricultural crops associated with the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution of prehistory and the settled communities that developed in both East and West. Then there are the subtropical and tropical crops distributed through the tropics during the European colonial expansion of the 18th and 19th centuries. Globally there are about 3000 known food plants of which about 150 have been extensively cultivated and traded. However, about 90% of the human diet consists of about 15 species and, of these, only four (wheat, rice, maize, and potatoes) make up much more than half of the world’s food supply. There are a further couple of non-food groups that fall under the umbrella term ‘domesticated plant’ – the ornamental plants used in parks and gardens, and plants of special practical use – for medicine, structural materials etc.

The second-order categories relate to the different kinds of plants themselves: root crops, cereals or grain crops,

Plant domestication – Hisitorical Background

Plant domestication is a crucial step in the evolution of human civilization, marking the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities. This process, which began thousands of years ago, fundamentally altered the way humans interacted with their environment, leading to significant advancements in food production, population growth, and societal development. In this account, we will explore the history of plant domestication, from its origins in prehistoric times to its impact on modern agriculture.

Origins of Plant Domestication The origins of plant domestication can be traced back to the Neolithic era, around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, when humans began to transition from a nomadic lifestyle to settled agricultural communities. This period, also known as the Agricultural Revolution, marked a significant shift in human history, as people started to cultivate plants for food, fiber, and other resources.

One of the earliest plants to be domesticated was wheat, which originated in the Fertile Crescent region of the Middle East. Wheat cultivation began around 9000 BCE, followed by the domestication of other cereals such as barley, oats, and rye. These early farmers learned to select seeds from wild plants with desirable traits, such as higher yield, larger seeds, and resistance to pests and diseases, leading to the development of cultivated varieties.

In addition to cereals, legumes such as lentils, peas, and chickpeas were also domesticated during this period. These plants provided a rich source of protein and nutrients, complementing the staple grains in the diet of early agricultural societies. Over time, farmers developed agricultural techniques such as irrigation, crop rotation, and soil management to improve yields and sustain their growing populations.

Spread of Agriculture The practice of plant domestication spread rapidly from the Fertile Crescent to other regions of the world, following trade routes, migration patterns, and cultural exchanges. In Asia, rice cultivation began around 7000 BCE, leading to the development of sophisticated rice paddy systems in countries like China and India. In Africa, sorghum, millet, and yams were domesticated independently, providing staple crops for various communities across the continent.

In the Americas, maize (corn), beans, and squash formed the basis of indigenous agriculture, with complex farming systems emerging in Mesoamerica and the Andes region. These crops were domesticated by ancient civilizations such as the Maya, Aztecs, and Incas, who built advanced societies based on agriculture, trade, and cultural exchange.

Impact of Plant Domestication The domestication of plants had a profound impact on human societies, shaping their economies, social structures, and cultural practices. Agriculture allowed for surplus food production, leading to the development of trade networks, specialization of labor, and the rise of urban centers. Cities like Ur, Mohenjo-Daro, and Teotihuacan flourished as agricultural societies expanded and diversified their economies.

The transition to agriculture also brought about changes in social organization, with the emergence of hierarchical societies, property rights, and governance structures. Agricultural societies developed complex systems of land ownership, inheritance, and taxation, laying the foundation for centralized states and empires. The control of food production became a source of power and wealth, leading to the rise of elites, priests, and rulers who governed over agrarian societies.

Technological Advances The practice of plant domestication spurred technological innovations in agriculture, leading to the development of new tools, techniques, and crop varieties. Early farmers used simple implements such as digging sticks, hoes, and sickles to cultivate the land, harvest crops, and process food. Over time, these tools were refined and improved, leading to the invention of plows, irrigation systems, and storage facilities.

Selective breeding played a crucial role in the development of new crop varieties with desirable traits such as higher yields, improved taste, and resistance to pests and diseases. Farmers experimented with crossing different plant varieties, selecting seeds from the best-performing plants, and adapting crops to different environmental conditions. These efforts led to the development of diverse crop species and varieties that could thrive in a range of climates and soil types.

Industrial Agriculture The industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries brought about significant changes in agriculture, as mechanization, chemical inputs, and genetic manipulation revolutionized food production. Farming practices became more efficient and productive, leading to increased yields, reduced labor costs, and the intensification of agricultural systems. Machines such as tractors, combines, and irrigation systems transformed the way crops were planted, harvested, and processed, allowing for larger-scale production and higher crop yields.

Chemical inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides were developed to boost crop productivity and control pests and diseases. These inputs allowed farmers to increase their yields and protect their crops from environmental threats, but also raised concerns about pollution, soil degradation, and health risks. The use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) further revolutionized agriculture, allowing scientists to introduce desirable traits into crops such as pest resistance, drought tolerance, and increased yield potential.

Challenges and Sustainability While industrial agriculture has led to significant advancements in food production, it has also raised concerns about its environmental impact, sustainability, and long-term viability. The intensive use of chemical inputs has led to soil erosion, water pollution, and biodiversity loss, threatening the health of ecosystems and the well-being of future generations. The reliance on monoculture crops and high-input agriculture has also led to concerns about food security, resilience to climate change, and genetic diversity in agricultural systems.

In response to these challenges, there has been a growing interest in alternative approaches to agriculture that prioritize sustainability, biodiversity, and regenerative practices. Organic farming, agroecology, and permaculture are examples of agricultural systems that seek to mimic natural ecosystems, promote soil health, and reduce reliance on external inputs. These practices focus on building resilient food systems, conserving resources, and supporting local communities, while minimizing the negative impact on the environment.

Future of Plant Domestication As we look to the future, the practice of plant domestication will continue to play a crucial role in feeding a growing global population, adapting to climate change, and promoting sustainable development. Advances in genetics, biotechnology, and precision agriculture offer new opportunities to improve crop productivity, enhance nutritional quality, and breed resilient crop varieties. Researchers are exploring gene editing techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9 to develop crops with traits such as disease resistance, drought tolerance, and improved nutritional content.

In addition, there is a growing interest in conserving and utilizing traditional crop varieties and wild plant species for their genetic diversity and adaptive traits. Crop wild relatives, landraces, and heirloom varieties contain valuable genetic resources that can be used to breed new crop varieties with unique traits and characteristics. Efforts are underway to preserve and promote these diverse genetic resources, while also supporting smallholder farmers, indigenous communities, and local food systems.

Conclusion The history of plant domestication is a story of innovation, adaptation, and resilience, as humans have cultivated plants to sustain their communities, advance their societies, and shape the world around them. From the origins of agriculture in the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China to the modern industrial agriculture systems of today, plant domestication has been a driving force in human history and evolution.

As we navigate the challenges of the 21st century – climate change, biodiversity loss, food insecurity – the practice of plant domestication remains central to our efforts to build sustainable, resilient food systems that can nourish and sustain the planet. By honoring the lessons of the past, embracing the opportunities of the present, and shaping the future of agriculture in harmony with nature, we can ensure a bountiful harvest for generations to come (AI Sider July 2024).

Plant domestication

‘Plant domestication’ is an ambiguous expression that generally refers to the human genetic alteration or selection of plants that can occur to a greater or lesser degree. In a strong sense ‘domestication’ includes some of our major cereal crops subjected to anthropogenic alteration on such a scale that they could not survive if reintroduced to nature. In a weak sense ‘domestication’ simply means plants that have been brought into cultivation. Some garden plants do not differ genetically from plants in the wild and, when they escape from gardens into the wild, they may proliferate to invade the natural vegetation. It is possible that in some countries ornamental plants have been brought into cultivation from the wild on only one or a few occasions. Though techncally they do not differ from plants growing in the wild they do represent only one part of the wild gene pool and are still, therefore, genetic selections. Sometimes forms of ornamental interest that are not recognized in their botanical names, for example some flower colour variants, may be brought into cultivation and given special cultivar names under the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants.

From a plant-centred or phytocentric perspective it might seem that human impact has been greatest as a consequence of domestication (although some would argue that it was the plants that domesticated humans). Domestication has three key components: moving them out of natural habitats and thus altering the natural plant geography, changing them physically by selection, breeding, and genetic engineering, in this way, and by cultivating them in various ways.

Time of introduction

Records of plant introductions can be misleading. Dates of plant introduction to a non-native country or region may be recorded when the plants were not put into commerce or general cultivation: later introductions might have been the ones that were widely distributed and their introduction may have been continuous or sporadic. Genetics is revealing more and more about the paths of plant geographic redistribution mediated by humans and may one day allow us to pin-point the original populations from which introduced plants were selected. Many countries received exotic plants indirectly from secondary sources rather than directly from their native populations so, for example, most of the plants introduced to the Neo-Europe’s would have come from their European colonial founders. In the early years of colonial settlement Australia’s agricultural crops and ornamental plants would have come almost exclusively from Britain.

La_Boqueria market Barcelona

We are attracted to the luscious colours of luscious fruits

Ripe fruit was a favourite part of the diet of our primate ancestors

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Dungodung Accessed 5 May 2017

Historical phases of introduction

Like so many other factors plant globalization began slowly, gathering pace over time through trade between different civilizations. Historically, several important phases of plant globalization can be discerned: the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution (c. 10,000-4000 BCE); the collection and redistributed of plants through the Roman empire (c. 100 BCE-400 CE); distribution by trade in the Islamic Empire (c. 600-1400 CE); then by far the greatest phase of plant dispersal that has been likened to the early phases of homogenization of world vegetation that occurred during the phase of European colonial expansion (c. 1500-1900). This was a period of exchange of tropical crops between the East and West Hemispheres, the introduction of temperate agricultue into new regions of the world and the import into Europe of ornamental plants from its colonies and colonial exploration when botanic gardens played a role in the redistribution of plants of economic importance.

In line with major factors relating to globalization and sustainability it is evident that factors influencing plant globalization include: population numbers, degrees of social organization, and technological developments influencing systems of transport and communication.

Records of domestication

Key information relates to the historical change that has occurred in geographic distribution of the major crops and the extent to which they are geneticaly different from their wild ancestors. The scientific value of the information in the timeline below would be greatly enhanced if all factual claims were referenced, an extended academic exercise taking too much time here. I have done what I can using the references listed and by accessing sources like Wikipedia. Clearly this list of domesticated plants is confined to major economic crops – it cannot extend to ornamental plants.

New World food crops

Food crops native to the New World of South America and the Caribbean included: avocado, cashew, cassava, chili peppers, cocoa, Jerusalem artichoke, peanuts, pineapple, pumpkin, French and runner beans, squash, sunflower, sweet potato, tomato, vanilla, and the staple cereal maize (corn). Crops

Old World and Asia

passing to the New World included: wheat, barley, rye, oats, apples, aubergines (eggplant), citrus, coffee, grapes, mango, olives, onions, peaches, pears, spinach, and tea, and from Africa especially came sorghum, henna, and watermelons.

From SE Asia

Came: banana, breadfruit, coconut, sugar, taro, yams, and plantains. There were additional economically important non-food plants: tobacco from tropical America, the rubber plant from Brazil, quinine from Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, opium from Eurasia, the fibres hemp and jute from Asia and sisal from South America, and cotton from the tropics and beyond.

Commentary & sustainability analysis

The process of plant domestication has been one of coevolution (see plants make sense) – indeed it may be claimed that plants domesticated humans. Possibly the most momentous change in human social history occurred when societies took up agriculture to live in settled communities. From this time the development of cities with hierarchical societies, division of labour, writing, complex cultures, and rapidly growing populations appear, in retrospect, to be almost inevitable.

Plant domestication timeline

BCE

9400-9200 Fig – Near East – The edible fig was one of the first plants to be domesticated by humans. Sterile (cultivated) figs have been found in the early Neolithic village Gilgal I in the Jordan Valley dating to about 9400–9200 BCE, thus pre-dating the domestication of wheat, barley, and legumes by about 1000 years. Figs were widely grown in Ancient Greece. Theophrastus observed that Greek farmers tied wild figs to cultivated trees to produce the fruit. Also grown by the Romans Cato the Elder lists several varieties (cultivars) in his De Agri Cultura, (c. 160 BCE, ch. 8) based on provenance: the Mariscan, African, Herculanean, Saguntine, and the black Tellanian. From the 15th century on it was grown in Northern Europe and the New World, the first record in the UK appearing to be in the 16th century (Cardinal Reginald Pole, Lambeth Palace, London)

8500 Barley – Near East – Wild Barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum) ranges from North Africa and Crete in the west, to Tibet in the east.[8] The earliest evidence of wild barley in an archaeological context comes from the Epipaleolithic at Ohalo II at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee. The remains were dated to about 8500 BC.[8] Cultivated The earliest domesticated barley occurs at Aceramic Neolithic sites, in the Near East such as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B layers of Tell Abu Hureyra, in Syria. Barley was one of the first domesticated grains in the Near East,[13] near the same time as einkorn and emmer wheat.[14] Barley has been grown in the Korean Peninsula since the Early Mumun Pottery Period (c. 1500–850 BC) along with other crops such as millet, wheat, and legumes.[15]

8500 Einkorn wheat – Near East – An early dwarf Cultigen of wild wheat found in archaeological sites of the Fertile Crescent and first domesticated approximately 10,000 years BP, the earliest DNA records traced to Karaca Dağ in SE Turkey. Cultivation spread from here to the Caucasus, the Balkans, and central Europe, favoured over Emmer in cooler climates but in the Middle East its use declined in favor of emmer wheat around 2000 BCE. Cultivated in some regions of N Europe through the Middle Ages up to the early 20th century

8500 Emmer wheat – Near East

8500 Chickpea -Anatolia

8000 Rice – Asia

8000 Potatoes – Andes Mountains

8000 Beans – South America

8000 Squash – (Cucurbita pepo) Central America

8000-6000 Bottle gourd – Lagenaria siceraria – Indigenous to Old World Africa, reaching East Asia (China, Japan) by 9,000–8,000 BP, widely dispersed in the New World by 8,000 BP from Asian stock. Not so much a food source but grown for the value of its hard-shelled, buoyant fruits used as containers, musical instruments, and fishing floats[1]

7000 Maize – Central America

6000 Broomcorn millet – East Asia

6000 Bread wheat – Near East

6000 Manioc/Cassava – South America

5500 Chenopodium – South America

5000 Avocado – Central America

5000 Cotton – Southwest Asia

5000 Bananas – Island Southeast Asia

5000 Beans – Central America

4000 Chili peppers – South America

4000 Amaranth – Central America

4000 Watermelon -Near East

4000 Olives – Near East

4000 Cotton – Peru

3500 Pomegranate – Iran

3500 Hemp – East Asia

3000 Cotton – Mesoamerica

3000 Coca – South America

3000 Squash (Cucurbita pepo ovifera) – North America

2600 Sunflower – Central America

2500 Rice – India

2500 Sweet Potato – Peru

2500 Pearl millet – Africa

2400 Marsh elder (Iva annua) -North America

2000 Sorghum – Africa

2000 Sunflower – North America

1900 Saffron – Mediterranean

1900 Chenopodium – China

1800 Chenopodium – North America

1600 Chocolate – Mexico

1800 Chenopodium – North America

1500 Coconut – Southeast Asia

1500 Rice – Africa

1000 Tobacco – South America

c. 100 Eggplant – Asia

c. 1300-1400 Vanilla – Central America