Plant lore

Wherever the poetry of myth is interpreted as biography, history, or science, it is killed. The living images become only remote facts of a distant time or sky . . . it is never difficult to demonstrate that as science and history, mythology is absurd. When a civilization begins to reinterpret its mythology in this way, the life goes out of it, temples become museums, and the link between the two perspectives becomes dissolved.

Joseph Campbell, 1993[2]

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553)

Painted 1530

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Several articles address the historical human relationship to plants, not so much in terms of plant utility but more through changes in attitudes and beliefs, and therefore shifts in plant meaning. This article on plant lore introduces the world of animistic beliefs of prehistory, Natura, when humans as hunter-gatherers were a part of nature itself, existing within nature, essentially as they had evolved from it. As communities grew, human environments were more man-made, hierarchies developed, writing emerged, and culture began to dominate nature – so the narratives of belief changed. Former animistic beliefs were now married to accounts of deities that populated spiritual but more human-like worlds, the deities, heroic sagas, and legends of Agraria. This system of belief reached its zenith in the rich recorded narrative of Greek mythology, outlined in a separate article for its insights into the changing human experience of plants. As cities expanded, the spirits of animism were lost, replaced by a polytheistic world of many gods, and eventually the monotheism of the Abrahamic religions.

The human relationship to plants involves not just the practical needs of the ‘body’ – foods, medicines, and materials etc. – but also the needs of the ‘soul’, the realm of attitudes, beliefs, desires and artistic expression. It is not possible to discover what our distant ancestors thought, felt and believed about plants without visiting the world of mythology.

Each culture has its own myths and legends that often share features with those of other cultures. For those inheriting the tradition of Western Culture, the mythology of the ancient Greeks stands out for its detail and depth of intelligent insight into human nature as its world of creators, gods, demigods, spirits, monsters, heroes, adventurers, sorcerers, enchanters and prophets engage us in an exploration of wonder, madness, cruelty, love and hate – the full range of human experience in all its beauty and horror. These are tales whose meaning is apparent to all, communicated not by precept but by the power of entertainment and allusion. They were stories familiar to all Greeks in their daily lives and reinforced at festivals as an oral poetic tradition told through the media of song and ritual.

This article can only set the general scene as needed for its special consideration of plants. For those wanting to follow Greek mythology in more detail there are references given at the end, including a recent easily-digested account by educated entertainer Stephen Fry, and a recommendation to visit the web site www.theoi.com.

Several articles address the question of changes in plant meaning over time. The article on plant lore introduces the world of animistic beliefs of prehistory, Natura, when humans as hunter-gatherers were a part of nature itself, existing within nature, essentially as they had evolved from it. As communities grew, human environments were more man-made, hierarchies developed, writing emerged, and culture began to dominate nature – so the narratives of belief changed. Former animistic beliefs were now married to accounts of deities that populated spiritual but more human-like worlds, the deities, heroic sagas, and legends of Agraria. This system of belief reached its zenith in the rich recorded narrative of Greek mythology, outlined in a separate article for its insights into the changing human experience of plants. As cities expanded, the spirits of animism were lost, replaced by a polytheistic world of many gods, and eventually the monotheism of the Abrahamic religions.

Included in this article under the heading of ‘plant lore‘ are many of our pre-scientific intuitions, fears, suspicions, hopes, desires and beliefs about plants. Emphasis is on the European plant lore that would have been brought to colonial Australia’s Botany Bay, but many of the general themes covered are universal.

We can quickly dismiss early beliefs as ‘myth’ a word which, when used in a derogatory way, means ‘fanciful’ or ‘illusory’ and, ultimately, with no foundation in fact. This may be a healthy rational attack on simple credulity, but it is also the rejection of plant world that is rich in meaning, colour, symbolism and humanity – as the quote at the head of this article suggests.

Myth is important to us today because it gives us insights into human nature (a major theme of this web site).

This article explores the undercurrent of European beliefs about plants and the land that were part of the European world that existed before Christianity became the prevailing belief-system (?mythology) in Britain in about 350 CE. Many of these early beliefs of prehistory were deeply ingrained in the language, literature and traditions of European peoples, and some have remained so to this day. Christianity referred to them pejoratively as ‘pagan’, although the ceremonies and beliefs were often absorbed into the Christian ritual and calendar.

Myth

What remained of the beliefs coming from former European hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic, the great early Mediterranean civilizations, the Celts, Gaels, Bretons, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans when Europeans set foot on the continent of Australia in 1789?

How exactly did the world of mythology influence English settlers and the way they related to the plants in the new land?

Significance today

From a modern perspective it is easy to be critical of all beliefs falling under the term ‘mythology’. As there is no means of determining the validity of supernatural beliefs and in accordance with the sentiments expressed by comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell at the head of this article, I ask the reader to suspend modern critical judgment and enter the intense and rich world of creative imagination that our ancestors occupied, the narratives that plumb the subconscious depths of our humanity, a world that can make our current imaginative world seem dry and lifeless. Such beliefs were not necessarily irrational superstition, they could be based on empirical evidence: after all, ‘If a plant can kill, soothe or intoxicate it must have an inner power‘.[1]

However, in trying to define what it is that makes myth so important we display our ambivalence. Myths are, on the one hand, treated as fanciful tales that are clearly untrue while, on the other, respected for expressing profound universal truths about human nature and the human condition that speak to all cultures and therefore deserving the respect often given to poetry, great literature, and religion. We can think of them as narratives that were part of a rich oral tradition passed from generation to generation containing the history of the world and particular peoples as cultural memory and record-keeping, explanations, and the accumulated wisdom about life and peoples. The Greeks themselves, some at least, recognised that mythic stories reflect ourselves, that culture instructs myth but that fanciful stories may be allegorical, containing subterranean truths. Perhaps they are a proto-scientific attempts to explain the unknown, a way of coping with fear and awe at a time when language describing abstract matters was in the early stages of development.

Purpose

Myths serve many purposes – as embellishment of the exploits of actual historical figures (legends, sagas), the personification of the powers of nature, as allegories or perhaps as, moral or religious tales.

As a subject it is generally studied as comparative mythology or comparative religion, including folklore. One of its most eminent early proponents was James Frazer (1854–1941) who wrote the two-volume Golden Bough (1890) named his book after Roman poet Virgil’s story in the Aenead of the Trojan hero Aeneas and the Sibyl who presented a golden bough to the gatekeeper for admission to meet Hades the ancient Greek god of the underworld.

In societies with an oral tradition myth was a means of combining entertainment and instruction. The power of myth is its capacity to communicate, through simple ceremonies and stories, human themes with great and universal impact: they draw attention to fundamental psychological paradigms that have always been manifest inhuman nature, the deep, possibly unconscious, psychological power of the eternal, universal and archetypal themes that express our humanity: creation, heroism, love, hate, jealousy, betrayal, revenge, death, the cycle of life and the seasons, immortality, and resurrection – elemental forces of nature like earth, air, fire and water; the heavens, earth, and sea; the Sun and Moon.

Joseph Campbell explains the function of those myths taken seriously through three key ideas in classical Indian philosophy: that all human striving (the sum of our innate biological drives) can be placed into two categories: karma – love and pleasure, and artha – power and success. These powerful human motivating forces are often the source of human conflict but they can only be controlled or harmonised by a social contract or agreement about what, within a particular community, counts for acceptable behaviour. This is the third key idea, dharma – lawful order, moral virtue and a sense of duty. The way this code of conduct is decided is not innate but a matter of education.

This then, according to Campbell, is the function of myth: to appease karma and artha through dharma – or, expressed in contemporary terms, regulation of social behaviour to facilitate day-to-day existence and the ultimate survival of the community. No doubt for this reason comparative mythologist Bruce Lincoln has described mythology as ‘ideology in narrative form’. Myth on the one hand reinforces karma, artha and dharma but also, through heightened mental states, provides a means of release from them.[1]

So that dharma can be effective it was, and is, almost invariably associated with supernatural authority as any authority attributed to fallible humans is open to criticism and subversion.

ampbell also summarises what he regards as the single universal theme of the many mythological legends of epic heroism which he terms the ‘monomyth’: ‘A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man’. Such a theme is as powerful today as it would have been when told round a fireside more than 10,000 years ago. We think of modern plagiarised variations: Wagner’s Ring Cycle, Mozart’s Magic Flute, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, even Kubrick’s A Space Odyssey, or the movie Star Wars. Is a kind of wanderlust, the desire to ‘go walkabout’ and explore that has been so much a part of our evolutionary history hardwired into our evolutionary psychology?

Mythology provides people with an explanation of the physical and spiritual world, its origins and meaning, and is generally associated with a code of behaviour. It provides what we might nowadays be called a grand narrative.

One aspect of myth is as proto-science, finding explanations for the unknown, for Hume it was fearful humans trying to cope but myth was not just a manifestation of fear it was also an expression of awe. During the Enlightenment and following Romantics myth was regarded as expressing profound innate truths under banal stories. While modern anthropologists lie Malinowski regard myth as a way of legitimating social norms.

Analysis

Rather than accepting a single school of thought modern students of myth use an analytic toolbox to help them unpack the meaning of myths – a combination of theories proposed by great mythologists of the past which draws on each as and when it seems applicable: functionalism (Bronislaw Malinowski 1884-1942) sees myth as legitimating cultural norms and social values, a way of endorsing the status quo; structuralism (Claude Levi-Strauss 1908-2009) maintains that the brain innately structures the world into binary opposites. Myth therefore often reflects these opposites and sometimes the anxiety that occurs when these opposites are challenged and some form of dialectic reconciliation much be reached. Examples would be challenges to culturally-accepted norms concerning food/not food, kin/not kin, and accepted norms concerning sexual matters such as incest, bestiality and homosexuality; psychoanalysis (Sigmund Freud 1856-1939) saw myth, which is extraordinarily explicit and brutal, as ‘dramatising events in every individual’s psychological development’. Freud, who was especially concerned with the unconscious mind, understood myth as living out the unconscious desires of an entire culture: it was a dream-like way of liberating unconscious feelings about matters that were socially important or unacceptable concerning, among others, food, incest, domination, fratricide, matricide and so on. So, for example, from Freud and Greek mythology we have the Oedipus and Electra complexes. Myth is also explained through the school of ‘myth & ritual’ as developed by Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) and Jane Harrison (1850-1928) who draw attention to the power of group experience or ‘collective effervescence‘. This, they claim, is at its height during ritual which is a stylised and transitional moment that marks a committment and anchors peoples’ lives. Often bizarre or unusual stylised behaviour related to ritual requires explanation and that is the role of myth.[Cousera Peter Struck Greek and Roman mythology]

Ritual

Myth would find expression through ritual. We can see how both secular and religious ceremonies, procedures, events, and observances of today find their origin in ancient ritual. We can list some of the forms they take: purification; special clothing; processions; dedications; fasting; special foods and drinks; sacrifices; libations of wine, oils and other liquids; banquets and feasts; use of secrecy; games, songs and contests; calendration of the year with festivals and other observances; use of sacred buildings and places; initiations and rites of passage.

Agents

The spiritual beings of mythology have been variously ranked in terms of their significance for the world and particular communities.

Relatively recent monotheistic religions provide a grand narrative that explains the origin of the world (cosmogony) and the place of humans in the present and after lives. Earlier polytheistic myths are ancient socially-sanctioned and often sacred narratives explaining the origin of the gods (theogony) and their roles. Sometimes they take the form of legends, epic stories, or sagas these entail accounts of great heroism that may be loosely related to historical characters and events.

At the other extreme are fables and fairy tales. Fables feature animals, mythical creatures, plants, inanimate objects or forces of nature which are given human qualities like speaking and they often serve as moral tales. Fairy- or folk tales, like Grimms’ Fairy Tales of German folklore or Jack-and-the-Beanstalk, are fanciful stories that often start ‘once upon a time’ and involve characters like elves, ogres, goblins and mermaids also, quite often, witches wizards, magic, and sorcery – compelling stories often now resurrected in different guise for entertainment as in films of Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings. Although they involve the supernatural they have no special spiritual or religious significance and are generally used as moral tales to guide child behaviour or simply scary entertainment.

Grander socially important myths were revealed to people through special religious mediators, a shaman, possibly a ruler, but generally a member of a priestly class of some kind. They invariably entailed ceremony and ritual through special people who could communicate with the supernatural in some way, as through: augury, lustration (purification), auspices (diviner of bird flight), libation (liquid offering), necromancy (communication with the dead), enchantment, witchcraft, communion, incantation, divination, séances, fortune-telling, palm-reading and so on. Frequently it was only through the intercession of these special people that admittance to the afterlife could be obtained.

Sources of mythological knowledge

How can we possibly know what people believed several thousand years ago?

Most of what we know of mythology comes to us from ancient written sources, immediately raising questions of veracity. In the absence of a written record we must fall back mostly on archaeological evidence, especially rock art, and what we can deduce about social history from recovered artefacts. A little information can be gleaned from genetics and linguistics which can help elucidate the migrations and movements of different peoples and the evolution of language and ideas. The European written record dates back about 5,000 years and it incorporates accounts of the oral history and traditions that had been passed down from generation to generation.

Stories in the literature are recounted with many variations, as they probably were even when at their most potent so there is little point in attempting to find authentic or ‘true’ versions. What is important is the occurrence of common themes, the similarities suggesting ancient origins as traditional stories passed between peoples throughout history as a result of trade and conflict, a measure of both the endurance of tradition and the power of the themes themselves.

Written

Primary sources commenting on the matters discussed here is difficult to assess for authenticity. In most instances there is probably much personal invention and bias. Accounts of ‘pagan’ literature and beliefs are no doubt coloured by the beliefs of the Christian writers who recorded them. Modern publications of old texts (such as the Old Testament) have also no doubt been subjected to considerable interpretative adjustment during editing and translation.

| CULTURAL GROUP | DATE | MAJOR WRITTEN SOURCES & COMMENTS |

| Druids (Celts)Pre-Christian | c. 5,500 BP | Stonehenge c. 5,500 BP the main features 3,500 BP. Accounts of Druidic beliefs come to us from unsympathetic (because opposed) accounts in Greco-Roman literature and records of Druidical teaching written by Christian monks that have survived in the medieval manuscripts and oral tradition of Bardic colleges in Wales, Ireland and Scotland which remained active until the 17th century. Neo-Druidism began in the 17th century. |

| Hindu scripturesVedic (Sanskrit) | c. 3,500 – 2,500 BP | Vedas are the oldest Hindu Sanskrit literature written c. 1500-500 BCE. The Rigveda probably dates to the Late Bronze Age at the earliest about 1,600 BCE |

| Abrahamic religionsChristianOld TestamentNew Testament

Muslim Quran Jewish Torah Talmud |

c. 1450– 450 BCc. 50-90 AD

c. 610– 632 AD (canonised 653-656 AD) |

Judaeo-Christian tradition long maintained that the Earth was created by God in 4004 BC. Contemporary studies indicate the content covers Middle Eastern history from about 1,000 BC to the period of Roman occupation of the Middle East in the first century AD. |

| Greco-Roman mythology | Ovid: Metamorphoses (Roman account of classical mythology 43 BC – AD 17/18) Roman myth: Virgil’s Aenead and Livy’s History | |

| Persian | Avesta written over several hundred years comprising the Gathas (or older Yasna) containing hymns possibly composed by Zoroaster | |

| Welsh, Irish, Manx | ||

| Anglo-Saxons | ||

| Vikings(Norse mythology) | ? | Sagas related by Snorri Sturluson |

| Shakespeare | 1564 – 1616 | Possibly the greatest British writer who knew full-well the power of the imagery associated with plant lore which pervades his work |

Some sources of mythological information

Printed herbals

Much of the folklore surrounding plants appeared in the first plant books published in Europe as Herbals. They were among the first books published using moveable type and known as incunabulae, covering a period of about 200 years from the mid to late fifteenth century. In these the plants, often referred to as ‘simples’ or ‘officinals’ and in America as ‘botanicals’ were described with their medicinal and other properties, referred to in the Herbals as ‘virtues’. Much of the medicinal information was derived from earlier, mostly Roman and Greek, sources but there are insights into local folklore. Prior to printed Herbals there were scrolls and manuscripts that had been copied or scribed and date back thousands of years. Among the few British manuscripts that pre-date the era of Herbals are the Anglo-Saxon Leechbook of Bald which was scribed in about 900 CE in Saxon vernacular and not derived from Greek texts. A Saxon manuscript copy of the Latin Herbarius Apulei Platonici in the Saxon language was produced in about 1000 CE and is held by the British Library, the original dating from the fifth century.[8]

There is little doubt that early belief s would have varied considerably from one local region to another. The very subjectivity of the topic and lack of hard factual information add further complication and imprecision to any studies. Even so it is still possible to get a taste of some of the main streams of belief in Britain as it arrived, first from Palaeolithic European people, the Celts who repopulated Britain after the last Ice Age from southern Franco-Spanish refugia and eastern continental Europe (Britain, Europe and Ireland were a single land mass at this time). With the Roman invasion of 43 AD came, first, the polytheistic Roman adaptations of Greek mythology to be followed by Christian monotheism after the Christian conversion of Emperor Constantine in 313 CE. To this was added the polytheism that arrived with continental Germanic peoples from today’s Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, and Faroe Islands.

Hunter-gatherer foragers

Can we ever know anything about the beliefs of those distant people who lived in Europe back in the mists of time before the last Ice Age in the late Palaeolithic or, for that matter, the hunter-gatherers of prehistory who peopled Britain after the last Ice Age about 10,000 years ago?

What we know of the European beliefs of the Palaeolithic and Neolithic suggest a certain uniformity of animistic beliefs (features and forces of nature occupied by spirits of various kinds) across Europe. Among the special characters mentioned again and again in the literature were the sacred groves and shrines that were located by rivers, headlands, mountains, springs, fountains, wells and other natural features. These sites were undoubtedly thought to be occupied by some sort of deity or spirit and it was therefore an appropriate place for a range of ceremonies, rituals, offerings and sacrifices to the spirit or god in an attempt to secure peace, food, and safety when journeying, or some other favour.

?In about 32,000 BP nude female figurines appear in the archaeological record made from bone, stone or mammoth ivory with expanded hips, large breasts as these were found in shrines it is assumed they were a form of mother goddess, becoming prominent in agricultural societies of the Near East and an indication of women as fertility symbols. Shamanism and animal totems.

Druids had special access to knowledge of the magical properties of many plants used in Druidical ceremony including: Vervain, Selago, Mistletoe, Oak (Quercus) and Rowan.p. xvii

What can be said about the beliefs of peoples that populated Britain after the last Ice Age and before the adoption of Christianity? Though writing is taken to have originated in about 5,500 years ago in Mesopotamia and there is the entirety of this record to explore for clues. What is clearly evident from this record (which includes the historical wanderings of nomadic tribes in the Middle East as portrayed in the ancient scrolls on which the Old Testament was based, written over 3,000 years ago). In general terms what we have, for the most part, are the works of urban scribes recording their times including the moral and political judgments of the day. To this can be added the oral remnants of nomadic hunter-gatherers and rural tribes which have made up the majority of this article, the plant lore, myths and legends, some of which we assume hint at beliefs held before the Neolithic Revolution. Perhaps unsurprisingly these myths and legends, though they do include a degree of moral instruction, are based more on the human relationship and dependency on the natural world: they concern the human relationship with supernatural forces to be found in the Heavens, Earth and Sea – the Earth, Air, Fire, and Water – and managing life through times of plenty and times of deprivation that were the annual cycle of the seasons. They are, in a sense, a guide to negotiating as smooth a passage as possible through life in nature.

The ancient character of many of these traditions and stories is hinted at through their parallels across cultures – like the close similarity in many of the themes of the Abrahamic religions.

Our oldest oral traditions hark back to times of magic and myth, superstitions, great ancient legends, song lyrics and the record of ancient social rituals, traditions including the use of natural products in medicine and pharmacy (pharmacognosy). Scientifically, these cannot be regarded as reliable sources. If, through a process of Chinese whispers, just a few people in a few minutes can distort factual information out of all recognition, then how seriously can we regard stories that potentially refer back several hundred generations? And yet … sometimes tradition is relentless rigid and even half-truths give us some insights?

There is a close connection between the myths and legends of India and those of western Europe.

On the dark side there were the potions and poisons that could be sourced from a florilegium of evil plants: Adder’s Tongue (Ophioglossum vulgatum), Hemlock (Conium maculatum), Mandrake (Mandragora officinarum), Martagon, Mistletoe (Viscum album), and Nightshade (Solanum nigrum): their effects could be counteracted with extracts and antedotes from other plants.

Neolithic farmers

Many myths treat the Earth anthropocentrically. Land is personified as a fertile mother (Mother Earth, the classical Terra Genetrix or Terra Mater). Mother Earth has given birth not only to humanity itself in the same manner as she now produces plants, but she also provides the nourishment that sustains all creatures. Stones are her bones, soil her flesh and grass her hair. For some cultures agriculture is therefore a form of mutilation that could render her infertile.[3]

A long tradition treats gardens as the domain of women. The great mythic female figures are all associated with gardens, Eve with the garden of Eden, Mary with Gethsemane, Venus with gardens in general. The wives of Greek and Roman statesmen managed the estates of their husbands one place where they were allowed some creative independence being in the garden. In Australian Aboriginal society the gathering and cultivation of plants for food was regarded as ‘womens work’, while the men did the hunting.

Such myths are frequently associated with fertility rites and a cyclical perception of time, every infant repeating, on a small scale, the history of humanity (ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny) formation of the foetus and its birth following the same path as the gestation and emergence of humanity from the dark depths of the Earth’s womb into the light, and at death returning to the Earth. In mythology there are numerous instances of babies coming from the Earth – from trees, swamps, streams, caves, and grottoes, anything suggesting a vagina. Caves especially had religious symbolism, being used not only as living space but also for burials and initiations. Agrarian cultures frequently associate agriculture, the tilling of the soil, with sexual intercourse, burial in the foetal position, often associated with these Neolithic communities, probably signifying a return to the womb.

Today we still seem to have a biological affinity with the Earth that is not simply a form of nationalistic patriotism, or a respect for our ancestors, or even an appreciation of landscapes … it is something deeper, a mystical unity or instinct that been named ‘biophilia’ by Harvard Biologist Ed Wilson.

Whatever beliefs were held by the Britons at the time of Roman conquest there is no doubt that the Romans would have brought with them the influence of the classical Mediterranean civilizations. Before the advent of Christianity, Roman conquest had frequently resulted in the absorption or adaptation of the mythology of the conquered people rather than its obliteration. What ideas would they have brought with them?

Mesopotamia

The cultures and mythologies of Sumeria, Mesopotamia and Akkadia (Assyria and Babylonia) thrived across the Fertile Crescent for about 4200 years from about 3500 BC to about 300 AD after which Christianity took hold. It was a polytheistic belief system with over 2,000 deities many of local significance only: it is certainly among the oldest ‘religions’ that we know of. For Abrahamic religions Mesopotamian mythologies are significant because of the overlapping accounts of topics like the Creation (the Mesopotamian epic Enuma Elish dating to about 3,200 BP similar to Genesis), Tower of Babel, the Garden of Eden, the Great Flood (see the epic of Gilgamesh) and several of the key figures. Legal codes of Babylonian-Assyrian regions have a similar form to the 10 Commandments. Manicheanism was a Mesopotamia-based fusion local elements with Abrahamic religions, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and flourished briefly around 200-300 AD.

Egypt

Egyptian legends were written mostly after the Early Dynastic Period (c. 5,100-4,700 BCE) and refer mostly to the Old Kingdom. Pyramid funerary texts from about 4,500 BCE include myths relating to the Creation, Osiris and the after-life and these are followed by those of the Intermediate Period (c. 4,200-4050 BCE) coffin texts. Later, the Book of the Dead, Books of Breathing, and other funerary texts date to the Late Period (c. 664-323 BCE). Greek and Roman writers, notably Herodotus and Plutarch, also provide their perspective on Egyptian beliefs in the Late Period.

Egyptian mythology was polytheistic although the particular gods in favour waxed and waned over time and were sometimes associated with particular geographic regions: they included the Sun god Ra, the creator god Amun, and the mother goddess Isis. Gods often shared human and animal forms in iconography, the depictions indicating more the god’s function that the way it might actually appear like the human torso with the head of a jackal (Anubis) or falcon (Horus). For a short time with the pharaoh Akhenaten there was monotheism under the god Aten. Ancient Egyptian mythology in general related strongly to the environment with all aspects of nature being part of a divine realm. It particularly related to the land, seasons, and the lifestyle of the culture. Great significance is placed on their dependence for life and light on the daily cycle of the Sun (Sun god Osiris), the annual flooding of the Nile which provided the fertility of the farmland soil. There are also concerns about flooding, famine, disease and the hostile and uncivilized surrounding peoples.

Intercession with the gods was through the ruler (pharaoh) who was generally considered to be a descendant of the gods and sometimes actually a true god, and there was a vast investment of resources into the offerings, dream interpretation, sacrifices, rituals (both daily and at other times), festival processions, and monuments of mythology.

Civilized fixed and eternal order, known as Ma’at (truth, justice, order) had been a part of the universe since Creation and it was always threatened by chaos. Humans had a life-force called ka which passed from the body at death (like a soul) but it still required food in the afterlife, as well as a ba, the unique spiritual make-up of a person that, unlike the ka, remained attached to the body at death. Beliefs about the nature of the afterlife and who would be part of it differed but in the Late Kingdom it often involved a day of judgment, the fortunate passing to the lush paradise of Osiris. In another version the souls of the dead would cycle the Earth through eternity with the Sun god Ra. Souls may be subject to various challenges and supernatural obstacles on the way to Duat (the underworld). In the Late Kingdom there was an increase in personal religion with local chapels and shrines.

Egyptian mythology remains with us today through their preoccupation with the afterlife as exemplified by Egyptian temples and extant massive mausoleums, the pyramids; symbols like the sphinx, solar disk; religious themes absorbed by the Greco-Roman and Christian traditions who respected Egyptian mysticism; its impact on literature and art

Greece

Greek mythology was grounded in the animistic beliefs of agricultural people who lived on the Balkan peninsula with accretion from Crete, Palestine, Phrygia, Egypt, Babyonia and elsewhere.[5] All nature was populated by a rich spirit world these spirits, especially in later mythology, assuming human form.

Invasion from the north brought a new heroic, militaristic and masculine culture and mythology, the old spirit world becoming of lesser significance. The Archaic period in Greece (800 – 480 BCE) was a period of ancient Greek history that followed the Greek Dark Ages and through the Greek classical era writers its mythology took on the character of a loose history of the world starting with its origin (cosmogony) and that of the gods (theogony) and humans, leading to a period of close interaction between humans and gods, and culminating in an earthly human Heroic Age highlighted by the Trojan War and its aftermath as exemplified in Homer’s epic Iliad and Odyssey.

Presiding over the Heroic Age were twelve supreme gods, the Olympians who lived on Mount Olympus where they ruled over Heaven and Earth lead by Zeus (Roman god Jupiter). Gods acquired their status through warfare but they also pursued knowledge, beauty and literature as well as other philosophical and creative pursuits. They were like supernatural humans with similar strengths and weaknesses. Beneath the Olympians was a vast pantheon of lesser gods many probably carried over or resembling spirits of the past, they included Nymphs (spirits of rivers), Naiads (who dwelled in springs), Dryads (tree spirits), Nereids (sea spirits), river gods satyrs whowere deities of woods and fields like Pan, the shepherd God. Then there were also the various spirits and deities associated with the underworld.

The oldest written myths can be traced to three main sources: Homer, Hesiod and The Homeric Hymns written c. 800 BCE no doubt incorporating themes from much earlier days.

Greek historians distinguished between the ‘real’ world that they wrote about and mythos a fable, story or tale that was not necessarily historically true but used to explain, control or influence the day-to-day world.

Rome

Romans wove Greek mythology into their own polytheistic belief system, aligning their gods with those of the Greeks (and to a lesser extent those of the Etruscans, parallels also evident with the gods of the Hindus) to create Roman equivalents so that the Greecian Jove became the Roman Jupiter, and so on and as such they appear in Roman literary works. Roman emphasis was more down-to-earth issues like heroism, politics, responsibility to the state, augury and ritual rather than creation myths and the like.

Accounts of Greek mythology read in Europe at the time of the Renaissance were mostly Latin in origin, so much of what we know of the Greek myths, including illustrations of its characters, has come to us from Roman authors like Ovid and his Metamorphoses.

As the Romans conquered new territory local gods were taken into their pantheon, often granting them the same honors as their own although this is not apparent in the case of the Druids.

Classical plant deities

Those who are the offspring of ‘Western’ culture cannot possibly confront the world of plants without first coming to terms with the Greek and Roman deities that depict or represent them.

In Greek mythology the nature deity Chloris was a nymph or goddess believed to have dwelt in the Elysian Fields and who was associated with spring, flowers and new growth. She was abducted by Zephyrus, the god of the west wind who, after they were married, transformed her into a deity known as Flora. Their son was named Karpos. Chloris is believed to have transformed Adonis, Attis, Crocus, Hyacinthus and Narcissus into flowers.

In Roman mythology Flora (Latin flos – flower) was a minor fertility goddess, a Sabine (Sabines were a prehistoric people who lived to the north of Rome) goddess of nature, flowers, youth, and the season of spring. She was, nevertheless, one of 15 deities that had her own flamen (a dedicated priest). Her festival, the Floralia, first instituted in 240 BCE with a special temple erected in 238 BCE, and was celebrated between April 28 and May 3 when men dressed up in flowers, the women wore risque costumes during five days of farces and mimes that included nudity, the sixth day allocated to the hunting of goats and hares. On May 23 a further rose festival was held in her honor. Flora possibly achieved greater prominence during a neo-pagan revival of Antiquity inspired by Renaissance humanists than she had ever enjoyed in Ancient Rome.

British Isles

The original inhabitants of the British Isles, the Celts or Britons, were subjected to several waves of occupation, first the Romans, then the Anglo-Saxons, followed by the Vikings and Normans. Christianity was introduced from the continent in about 350 CE. This created a rich cultural background.

Celts

Iron Age (1200 BCE – 400 CE) Celts in Britain were a disparate and ill-defined people and in the absence of a written record it is difficult to assess if there was any political or cultural collaboration and common heritage of beliefs. It seems safe to assume that Iron Age polytheism varied considerably from one locality and tribe to another.

Christianity

Physical evidence of Christianity in Britain dates from about 200 CE although actual archaeological finds confirming practising Christian communities only appear in the 3rd and 4th centuries. It was a completely new body of spiritual thought that arrived in Britain in the 3rd and 4th centuries, was superimposed on the beliefs of prehistory and the Romans invaders. Christianity existed alongside traditional rural belief systems, gradually taking hold across the Romanised southern part of the country.

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon migration into Britain began in about 450 AD bringing its own mythology. Roman accounts of the Gauls tell us that they were animists who ascribed a spirituality to lakes, streams, mountains, and other natural features, although this was human-like in its characteristics. There was animal-worship, their most sacred being the boar, emblazoned on Gallic military standards in the same way the Romans used the eagle. There was also a system of gods and goddesses some being worshipped by all and others specific to a tribe or even household.

However, in about 601 CE Anglo-Saxon King Aethelbert was baptised into the Christian faith at a time when Anglo-Saxon tribes had united into seven major kingdoms.

Vikings

During the 9th to 10th centuries Christianity was subjected briefly to the influence of Norse mythology which was the Germanic belief systems of invading Scandinavian Vikings. However official documents are now referring to traditional beliefs under the dismissive terms ‘pagan’, and ‘folklore’.

Anglo-Saxon and Norse mythology incorporates the pre-Christian myths of Germanic peoples of north-western Europe. Much of what we know comes from the epic poem Beowulf by an unknown Anglo-Saxon poet, written between about 700 and 1000 AD but relating to former mythic times in Scandinavia.

We also know that much of Anglo-Saxon mythology was written down by Christian scholars: it was polytheistic with major deities, most notably Woden, commemorated within the language as days of the week and in defiance of the names of Roman gods (except Saturday).

| DAY | OLD ENGLISH | GOD | ROMAN VERSION |

| Monday | Mōnandæg | Moon(Norse god Máni) | Lunar |

| Tuesday | Tiwesdæg | Tiw | Mars |

| Wednesday | Wōdnesdæg | Woden(Odin, Norse) | Mercury |

| Thursday | Þūnresdæg | Thunor(Norse Thor) | Jupiter |

| Friday | Frigedæg | Frija | Venus |

| Saturday | Sæturnesdæg | Saturn | Saturn |

| Sunday | Sunnandæg | Sun(Germanic goddess Sól/Sunna) | Sun |

Days of the week

Along with the major gods were lesser spirits to be found in nature, including elves, dwarves and dragons and there was certainly some magic and witchcraft: there may have been some shamanic rituals, and kings of the period claimed ancestry from the gods.

Society was based around kings and ceremonies included sacrificial offerings made at certain festivals of the year along with ritual burials (which varied from cremation to inhumation). There was even at this time some trade and communication with the wider world indicated by the presence of cowrie shells in mostly female graves (only found in the Middle East and Red Sea), Ceremonial sites included both buildings for worship with an altar and effigies but also places on high ground, wells and sacred trees. Sixty sites of worship have been detected through Anglo-Saxon words meaning ‘place of worship’ that occur in English place names.[5

Norse mythology, mostly preserved in Icelandic sources dating from the 11th to 18th century, had gone through more than two centuries of oral preservation. From this we are told the world consisted of nine kingdoms united by the branches of the tree Yggrasil. There are echoes of Anglo-Saxon elements as these kingdoms include giants, elves, dwarves, fire, hell for the wicked and various monsters and an assorted pantheon of gods overseen by Odin, the greatest. Legends also includes supernatural animals, heroes and kings. Ogres and trolls were Norse creations and in in Scandinavia dreams of terror were brought to the sleeper by mara, a horse-like creature, hence ‘nightmares’.

By Tudor times early fables, like those of Robin Hood, King Lear, The Blue Hag of Leicester (Black Annis), and King Arthur were being replaced among the educated by stories from the Greek myths.[4]

Mythology as encountered by us today through language, traditions, festivals, some rituals and superstitious actions are a complex mix from a past that, like us, borrowed, modified, passed on to future generations through unthinking tradition, and invented anew. We can best understand where nature and plants fitted into mythology by examining its main themes.

Normans

By the time of the Norman invasion in 1066 the strength of Christianity would have strongly tempered any further ‘pagan’ influence although there are many that remain to this day in Western culture.

Christianity, it seems, at different times either attempted to obliterate ‘pagan’ beliefs or to adapt them to Christianity. Deuteronomy 12.2 urges that ‘Ye shall utterly destroy all the places wherein the nations which ye shall possess served their gods, upon the high mountains, and upon the hills, and under every green tree’

Polytheism and monotheism

Christianity had emerged about 2,000 years previously in the Middle East. It was subsequently promulgated through the Roman empire following the conversion of Constantine the Great (Roman Emperor from 306 to 337 AD) and declared the official religion of the Roman Empire in 391 AD.

Christianity came to Britain from the melting-pot of the waxing and waning Mediterranean empires of the Egyptians, Etruscans, Minoans, Phoeniceans, Greeks and, above all, the Mesopotamians (Babylonians). Without exception these cultures were polytheistic, a situation posing inherent difficulties. Firstly, how should the various gods within a particular culture be ranked against one-another? But, more controversially, as lands were subjugated, how to evaluate your own gods in relation to those of a subjugated people. This could take the form of claim and counter-claim about the true or real gods (‘my gods are better than your gods’) or there would be an attempt to cruelly obliterate the belief systems which was not an easy matter. Another less drastic approach was to try and absorb or incorporate new gods within the existing scheme. Perhaps the Roman Pantheon (commissioned by Marcus Agrippa 64/63 BC – 12 BC) as a temple to all the gods of Ancient Rome, and rebuilt by Emperor Hadrian in about 126 AD) is a good example of similar imperial buildings containing sculptures and effigies of gods of the ancient world.

The Greek Parthenon completed in 438 BC was dedicated to one deity the goddess Athena and converted in the 5th century AD to a Christian temple for the Virgin Mary which, after the Ottoman conquest, became a mosque in the early 1460s. This too presented dilemmas: at one extreme the sculptures themselves were regarded as gods, more often as images symbolising the god but acting as a focus of worship, sacrifice and offerings. To others the whole idea of a physical object representing the spiritual realm was abhorrent because the image became the focus of devotion rather than the ideals that it represented (this was the despised worship of ‘idols’ and ‘graven images’).

Although Christianity became the official cosmogony of western England there was Celtic resistance from the western Britons, as well as the Anglo-Saxon and Norse tribal resistance to any Romano-Christian take-over of their long-held traditional beliefs, especially as these beliefs addressed their relationship to plants and the natural world

Over time Roman Catholicism deferred somewhat to traditional beliefs by absorbing ‘pagan’[10] festivals, feast days, religious sites, beliefs, and buildings into its own dogma and religious calendar. Some echoes of these non-Christian beliefs, though of little historical consequence, have continued to the present day within the layers of mythology and tradition that make up British mythology.

Themes

Cosmogony

Like the Aboriginal Dreaming, plant lore and legends were also a cosmogony – explaining the creation and the origin of things – but it was strongly based on a way of managing (or negotiating) a relationship with the land. With the emergence of cities nature becomes of much less significance in peoples’ lives. There is still a connection with nature because of the seasonal and unpredictable dependency on crops, but it is a different kind of relationship and less to do with trees, groves, forests, animals, birds and the landscape. With the advent of cities the paramount concern became people and their city environment: they needed to manage property and relationships. Above all they needed agreed codes of behaviour. Christianity was essentially about humans and their relationships. Though nature is present, especially in the writings of the Old Testament, it is peripheral to the main themes. There is no perceived need to negotiate with or establish any code of behaviour in relation to the land, only a moral code for human interaction. In this sense, Christianity is an urban religion. It does not seem remiss to claim with comparative mythologist Mircea Eliade, that prior to Christianity and large cities, much of humankind “had not so much a consciousness of belonging to the human race as a sense of cosmological participation in the life around him”p.166

Plant lore gives us an insight into the attitudes and beliefs about the natural world that predate the Renaissance, scientific plant nomenclature, the theory of evolution.

Firstly, regardless of our present-day perceptions it is without doubt the world of plant lore that truly connects us with our ancestors, people who lived in a close connection and dependence on the land that we have not experienced for many generations. Do we have some psychological affinity for these powerful themes, not just because of their universal but because of our psychological inheritance?

Secondly, there is the power of many of the mythological tales themselves precisely portraying the great universal themes that of humanity, of love, betrayal, and heroism acting out our follies, foibles and aspirations in some cosmic super-world of fallible gods. Powerful imagery like this has been plumbed by psychology, and in particular Freudian psychoanalysis with the Oedipus and Electra complexes, nymphomania and the analytical psychology of Carl Jung with its psychological ‘archetypes’, a sort of mental substrate or predisposition that is different from instinct and which is triggered by mythic imagery, journeys of spiritual transformation which he called ‘individuation’, and his studies of religion – all find their wellspring in mythology.

Firstly, as the quotation at the beginning of this article implies: it is easy, in the presence of modern science, to dismiss comparative mythology as so much bunkum: something that, in an enlightened society, we have grown out of. But there are a host of questions that should give us pause for thought. It is easy to dismiss them as quickly as entertaining but ignorant fantasy and superstition. Plants nowadays are ’just’ plants – they look nice and we eat some of them. Just a few generations ago they were enveloped in a rich symbolism and anthropomorphic identification. Flowers could attract love, they could be used to counteract spells and curses or call up supernatural intervention in our affairs. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that for all the anthropic sympathy and antipathy they evoke, they were nevertheless companions both in life and death, brightening the hard times with colour, form and scent. We give them to our sick and loved ones, we use them at funerals and festivals and in our daily life surround ourselves with them in a our gardens.

Greco-Roman mythology has always been a strong component a classical English education in England’s private schools. Every well-educated gentlemen would have known the major Greek myths. Though Greco-Roman mythology was never treated as a factual account its powerful themes and heroic tales had a strong influence on the literature, politics and culture of the British – and by this means was passed to the West in general. For the British the only complete education at this time was in the English public school tradition which was firmly grounded in the classics which were undoubtedly part of the mind-set of the public-school-trained leaders of imperial conquest (see ). It was educated men like this, generally referred to as ‘gentlemen’, who were respected within the British community and selected as its leaders. They were regarded as coming from respectable, sometimes noble, families and possessing both property and independent means. Among such people we can include Joseph Banks.

An Earthy Paradise

Nostalgia for paradise, an earthly or heavenly utopia of peace and plenty in a garden setting, has been a universal theme from ancient history to the present day. In Christianity it comes to us through the concept of Eden in the story of Creation, human knowledge and original sin. Though the idea probably originated in Egypt it is a special component of Persian mythology.

The Garden of Eden

Painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) in 1530

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Trees

The scale and majesty of trees commands both respect and awe. Little wonder that mystic world-trees have a central role in the cosmogonies (creation stories) of ancient mythologies, religions and belief systems, are the venerable source of wisdom as the ‘Tree of Knowledge’ or ‘Tree of Life’ and consequently the subject of tree-worship (dendrolatry). Tree branches and roots link the firmament and its deities to the spirits of the underworld, while the canopy provides a perfect sanctuary for meetings and rituals of the living as they connect with these spiritual kingdoms and the spirits themselves.

The tree is therefore a connection between the Earth, Heaven, and the Underworld and in some belief systems they were the source of humanity itself.

Tree worship seems to have been a universal feature of Palaeolithic cultures. Roman historian and chronicler Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE), for example, notes in his Natural History that ‘trees formed the first temples of the gods, and even at the present day, the country people, preserving in all their simplicity their ancient rites, consecrate the finest among their trees to some divinity‘.

Deciduousness symbolizes rebirth-resurrection while evergreens symbolize eternal life. Vedic and Scandinavian mythologies tell of trees generating or shading the Earth. Similarities in mythological stories indicate their ancient origins. Indian, Chinese and South American legends all tell of souls that climb to heaven from a tree.

Ancient Egypt trees were thought to be occupied by deities, notably the fig, Ficus sycamorus.

Iran mythology there was a World Tree at the centre of Paradise, a cloud-tree supplying fruit to the gods and it is from a tree that the first man and woman were formed (modern evolution confirms that humans ‘descended’ from the trees). The Iranian world tree was Haoma (equivalent to Gaokevena of the Zendavesta) and a sacred vibnne of the Zoroastrians. It too produced the drink of immortality and grew in the Fountain of Life in a vast lake, Vouru Kasha, alongside another mother tree that produced all plant life. In Persian mythology the cypress was especially sacred as it also was in India, symbolising eternal life.

Scandinavia Norse mythology tells of the World Tree, the Ash (askr) Yggdrasill whose roots pass through the centre of the Earth to form an axis mundi (centre of the world) that fixes Earth and connects it to the heavens, the stem bursting from the tip of a mountain, its branches forming the celestial sphere, its leaves the clouds and its fruits the stars. God Odin hung from its branches to obtain wisdom.

India VedicHindu scriptures describe a tree that symbolises all life and immortality, a Tree of Paradise that is the source of ambrosia, the nectar drunk by the gods that gives them eternal life, the Rigveda equating the tree to the Brahma, all the gods making up the branches which embrace the Universe. The sacred cosmic or world tree of Hindus is ashvattha, the Sacred Fig. Buddhist teachings also mention the Sacred Tree of the Buddha (mostly deemed to be Ficus religiosa, but occasionally Ficus glomerata, Jonesia asoka, Musa sapientum and sometimes the palms Butia frondosa or Borassus flabelliformis) as imparting wisdom and ambrosia but also yielding life-giving rain and serving as a haven for souls of the blessed. It is smothered with multi-coloured gems that shimmer like the plumage of a peacock. Under this tree the Buddha struggled with temptation and supernatural forces focusing his mind to ever higher levels of abstraction until, finally, triumphing over Earthly distractions to achieve Enlightenment. In Hinduism the evergreen broad-leaf tree known as Rudraksha (Elaeocarpus ganitrus) is the traditional source of seeds used as prayer beads.

AssyriaAssur, supreme deity of the ancient Assyrians was closely associated with a Sacred Tree, sculptures depicting worshippers kneeling in front of it and hanging offerings from the branches. Phoenicians constructed effigies of a Sacred Tree by their temples and these marked the place for sacrifices: on festival days the tree was hung with flowers and ribbons.

Trees were a symbol of stability and order. Though not conclusive it is likely that the columns and pillars used so much in classical architecture are symbols of tree trunks and the sacred grove (their capitals frequently decorated with vegetational motifs) and therefore imbuing buildings with religious significance.

Hebrew Judaic Rabbinic traditions spoke of a Mosaic Tree of Life which grew at the entre of the Garden of Eden.The Old Testaent of the Bible has many references to sacred groves.

Christian teachings place Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden which contained the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge. Adam ate fruit from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge of good and evil thereby committing ‘original sin’ which was the reason God sent his son Jesus to earth to redeem humans, allowing them eternal life. Pagan tree worship was so difficult to eradicate that Christianity (see for instance a letter from Pope Gregory to Mellitus, Bishop of London in 601[11]) Christianity conflating trees and the cross or crucifix with a ‘holy tree’ on which Jesus was crucified. Celtic goddess Brighid became the Christian saint of the same name, the vine became sacred as the source of wine for the Eucharist and in Medieval times grave slabs in both Britain and Scandinaviacasrried the symbol of the tree.[12]

Germanic mythology related the birth of children to cavities in trees and described a tree, Irminsul, that formed a pillar holding the universe in place.

Greco-Roman mythology traces the origin of humanity to a cosmogonic Ash tree, Melia, daughter of Oceanos. There are many variations to this theme, Hesiod equating Jove as the creator of the Ash tree and Roman mythology as presented by Virgil, Juvenal and Ovid replaced the ash with an oak. It has even been suggested that the columns of classical architecture are references to the mythic tree trunks that held up the world.[9]

Much of the Greek mythology would have dated back to pre-history and hunter-gatherer societies but the Homeric Olympian gods were the gods of a conquering aristocracy, not the fertility gods of nature and agriculture although nature was not excluded.

Jupiter’s sacred tree was the oak, and oak groves were sacred to goddess Diana. Major trees included the poplar, pine, cypress and plane gods being associated with individual trees or sacred groves. Individual trees were dedicated to famous people – a tradition which continues today in the planting of ‘commemorative trees’.

Both Greek and Roman mythology was peopled with the stuff of male sexual fantasy. In Greek mythology especially nymphs (young nubile female spirits who loved to dance, sing, and make love) were to be found everywhere and of several kinds: naiads (who presided over fountains, wells, springs, streams, brooks and other bodies of freshwater); nereids who lived in the sea, and were not to be confused with the alluring Sirens; and dryads, tree nymphs who dwelt in trees, groves and forests. Hamadryads were associated with specific trees, the two favourite trees being the oak and ash (Gk drys-oak). In some mythologies every tree had its presiding deity.

From trees were obtained forked wishing-rods and divining rods (in the form of lightning and a crude human effigy) and magic wands. The forked dichotomous branching was also characteristic of the branching pattern of the Mistletoe that was central to Druidic practice.

Celtic (Druidic) tree worship occurred across Britain and Europe and was never completely erased by Christianity, it persists through the traditions of the may pole dance and the Christmas tree with its offertory decoration whose pagan origins are barely remembered … a reminder of the power and persistence of tradition. Individual Celtic tribes in ancient Gaul were associated with particular trees. The Ark and the Cross. In Celtic tradition the Yew clearly had a special place from its use of its wood for wands and divination forks, and its frequent presence in cemeteries and churchyards sprigs of its foliage sometimes found in burial shrouds. It may have ben a surrogate for the cedar and palm so imporant in the biblical Middle East.

Today there may be as many as 3,000 holy wells in Ireland, many associated with trees, mostly hawthorn and ash.[13] Under Brehon Law which governed Early Medieval Ireland trees were aggregated into groups of seven according to their significance, the most important being the ‘chieftain trees’ (oak, hazel, holly, yew, ash, pine, apple) and ‘peasant trees’ (alder, willow, hawthorn, rowan birch, elm, idha). Accounts of trees in Celtic mythology rank them in different ways but most are associated with special powers or spirits giving rise to the expression ‘fairy tree’ which on the Isle of Man, the phrase ‘fairy tree’ denotes the Tramman elder (Sambucus nigra). Accounts of Celtic mythology associated with particular trees can be found in James McKillop’s A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (1998). Fagus, the Latin name for the Beech tree, was a Gallo-Roman god.

Folkard classifies the legends of flowers into the mythological, ecclesiastical and the poetic.

Also the planting of commemorative trees often to mark the birth of a child, like a human the tree grows to maturity when it reproduces and in its senior years provide provides shade, shelter and protection.

Ascension into heaven via a tree (Jack and the Beanstalk etc.).

The sacred grove is a consistent theme in almost all cultures. Even after the Norman conquest in Britain trees marked places of assembly, especially the local government ‘hundreds’ , named as such c. 960 CE.

Flower worship

Roman Catholicism appropriated pagan traditions of flower worship by first dedicating certain flowers to saints and martyrs known as ‘Our Lady’s Plants’ before later adopting a calendar in which each day of the year was represented by a flower. Much of the Greco-Roman mythology is embodied in plant names the transformation of youths and nymphs into flowers reflected in names like Daphne while Catholic monastery monks created names reflecting saints and martyrs. Greco-Roman mythology exerted a powerful influence over western classical education and its literature that is only now receding into the past. Evocative legends like that of the lecherous satyr (man-goat) Pan who pursues a coy nymph called Syrinx (nymphs were nubile female nature deities often associated with a local land feature: they were devoted to dance, song and making love) running to the bank of a river she appeals to her friends for help so they allow her to escape by being transformed into a reed from which Pan fashions pipes (pan pipes) that play haunting and seductive but sad music, evoking his lost love. In India animal sacrifice, a part of Vedic worship, was largely replaced in Hindu ritual by worship with flowers (puspa-yajana)

The Language of flowers

Throughout history plants have been used as symbols, specific plants being attributed with particular meanings. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet the bard refers to ‘rosemary for remembrance’ and there are many other examples. But it was in the Victorian era that this became a fashion in popular culture, rather like horoscopes, with many books published and lists compiled to titillate and amuse: carnation for pure love, daisy for innocence, orange blossom for chastity, etc. A French book, Le Langage des Fleurs by Charlotte de la Tour and published in 1818 was translated into English in 1834 and sparking a new fad that would last for about 40 years appealing especially to young ladies in both England and America.[15]

Doctrine of signatures

Paracelsus (1493-1541) was a bombastic German-Swiss physician to whom is attributed the belief that that plants indicated by their form the medicinal and other effects they would have when ingested – that their medicinal use could be ‘read’ from their signatures. So, for example, heart-shaped leaves of the trefoil could be used for heart conditions. Famous English botanist William Turner (1508-1568) described its use in the treatment of haemorrhoids a plant known as Pilewort (although it was better known as Lesser Celandine), Ranunculus ficaria (whose Celtic name was Grian-the Sun), the roots hanging like a bunch of grapes.

Plant names

There can be little doubt that by naming an object we feel a sense of power over it, even though the naming itself has few if any practical consequences: it is like the sense of relief when we are told what ailment we have or the name of a plant that we have been curious about.

Much fascinating information is buried in plant names themselves. Scientific binomial plant nomenclature (use of a two-word species name consisting of the genus name with its specific epithet) arose out of the vernacular use of binomials in common names in much the same way as we name ourselves. This was Swedish botanist Linnaeus’s initiation of the scientific system of names we use today. Before Linnaeus this time in Britain were the names of folklore in the regional languages and dialects. Linnaean names. By tradition plant names in the scientific system are presented in Latin form, most of them being of Greek or Roman origin although examples of names can be found that originate from Asia, Europe, Scandinavia, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon words and more. One example will suffice. The Latin scientific name of the Parsley is Petroselinum which is derived from the Greek πέτρος- rock σέλνον-plant. Use of the Latin word resulted in a gradual change of the Latin name to a common name: from Petroselinum to petersilie to percely, persil and parsley.[6]

Place names

Some linguistic insight into the past comes from the history embedded in place names as, for example, many British place names incorporate configurations of words that we know mean ‘sacred grove’ or ‘holy place’ others relating to woodlands, specific trees (Holyoak) and so on. These can be traced through the range of Celtic to Norman origins.[14]

Festivals

We clearly feel a need for (and have therefore retained) festivals that are based around the themes of beginning, renewal and regeneration and unrelated to Christian tradition. Most notable would be our New Year celebrations but also unusual traditions and ceremonies relating to birth and marriage, our first occupation of a new house along with the Easter (named after the Anglo-Saxon goddess Eostre) Festival combined with the Christian celebration.

Roman festivals included Robigalia (25 April) for a successful grain harvest while in the Christian calendar Rogation days were a time when parishioners patrolled their boundary saying prayers for their harvest.

May Day

May Day Festival in England dates back to at least the 16th and 17th centuries and incorporates much of the pre-Christian ethos based on nature. Celebrations, which included Morris Dancing (the name possibly derived from 15th century ‘Moorish Dance’), Maypole dancing (the maypole representing a tree and the ribbons the garlands and offerings that were an integral part of tree worship), and a May Queen who would be crowned with May blossom (Crataegus). Pre-Christian celebrations would celebrate Flora the Roman goddess of flowers and in the Middle-Ages works guilds would compete. Underlying such celebrations was an acknowledgement of two natural cycles: the annual cycle of the seasons and the human cycle of birth, maturity, decline and

Halloween

Halloween (a contraction of ‘All Hallows Evening’) is celebrated annually in many countries on October 31, the eve of the Christian feast of All Hallows (or All Saints). Typical festivities include the ‘trick-or-treat’ and other pranks, hanging up pumpkins carved into faces (‘Jack-o-Lanterns’) with a candle inside so that they glow eerily at night, costume parties, apple-bobbing, bonfires and various games and activities that conjure up haunting and horror. This has all the indications of Celtic festivals that were later added to the Christian calendar but the exact source is unknown – possibly a Western European harvest festival, ’festival of the dead’ or the Celtic Samhain.

Harvest festival

There can be little doubt that the harvest festival (OE hærfest – autumn) is an annual thanksgiving of the Christian church whose celebration incorporates ‘pagan’ mythology and ritual. It was generally held at or near the Sunday of the Harvest Moon which was the full moon closest to the autumn equinox, generally about Sept. 23rd when the reaping of grain and crops was complete for the year. There is a traditional English ballad and folk tale about John Barleycorn that amalgamates Christian and pagan ritual concerning the farming cycle of birth and death and the assembling of the threatening effigy called a Wicker Man sometimes associated with human sacrifice. Among the traditions still practiced there is the ‘corn dolly’ whose origins Encyclopaedia Britannica traces to ‘the animistic belief in the corn [grain] spirit or corn mother’. Apparently in some regions farmers believed that a spirit lived in the very last sheaf of grain that was harvested and that their gathering would render in homeless. Sometimes it was removed by beating the sheaf on the ground. In other places blades of the cereal were woven into the ‘corn dolly’ which they kept for ‘luck’ as a home for the spirit until seed-sowing the following year when it was ploughed into the soil as a blessing for the new season’s crop. Comparative mythologist James Frazer discusses the ‘Corn-Mothe’r or ‘Corn-Maiden’ in chapters 45-48 of The Golden Bough. The word ‘dolly’ may be a corruption of the word ‘idol’ or come directly from the Greek word eidolon meaning and apparition, or an object that represents something else.

In Gaelic tradition the harvest festival marks the onset of winter and is celebrated between 31 Oct, and 1 Nov., mid-way beween the autumn equinox and summer solstice and making upone of the four annual seasonal festivals (others being Imbolc, Beltane and Lughnasdh) that were celebrated in Scotland, Ireland and the Isle of Man.

New Year (Hogmanay)

A celebration of the mid-winter winter solstice that was observed by Germanic peoples and referred to in month names (e.g. Ærra Jéola– Before Yule or Jiuli, and Æftera Jéola-After Yule) and associated with the Yule log,Yule singing, Yule goat and Yule boar within the Norse, Gaelic and Celtic (Samhain) traditions and in some regions absorbed by the Christian tradition of Christmas. For the Vikings Yule involved the ‘Twelve Days of Christmas’ between what is now mid-November and early January and known in Scotland as the ‘Daft Days’ It was stifled during the Protestant Reformation but re-emerged near the end of the 17th century. Scholars have connected the celebration to the Wild Hunt, the god Odin one of whose many names is Jólnir, and the pagan Anglo-Saxon Modranicht.

We still need the Gods of Olympus and Roman gladiators of the Colosseum but today they fight it out on an enclosed playing field of green turf. We still fight over territory, feel suspicious of unfamiliar people. We see the evidence of male domination so prevalent in ancient mythology.

Christmas

Though Christmas (Christ’s Mass) is essentially a festival celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ it is associated with many pre-Christian traditions, like feasting, drinking and merrymaking – suggesting a ‘pagan’ festival too that reaches deep into many ancient European traditions. Little can be said of any certainty but there are many appealing explanations of the Christmas rituals that we all follow each year without pondering on their origins.

Though the modern tradition of the Christmas tree is said to be of relatively recent German origin (the expression ‘Christmas tree’ first appeared in the English language in 1835) there is every indication that both it and the associated decorations, garlands with gifts (like offerings) at its base, together with the prominence of holly, ivy, greenery, and especially mistletoe (a favourite of the Druids) go back to times of tree worship and ancient rituals related to the winter solstice. This would seem to be a case of Christian accretion and reinterpretation of ancient traditions (e.g. the red berries of holly representing the blood of Christ, emphasis on (ever) green foliage and wreaths (Advent wreath) relating to eternal life). Gift giving was a key part of the Roman Saturnalia festival of late December when slave owners would change roles with their slaves and give them presents, a tradition probably associated in more recent times with Boxing Day when gifts, a ‘Christmas Box’, were given to servants and tradesmen. There is also the associated with the Turkish St Nicholas 270-343 CE (merging with the Dutch Sinterklaas or Santa Claus and the slightly different perceptions of Father Christmas) and the gifts of the Wise Men to the infant Jesus. During the Protestant Reformation of the 16-17th centuries the Christ Child (Christkindl or Kris Kringle) became the provider of gifts.

Plant mythology today

From the 21st century we can barely imagine such times. For everyone death could come quickly and unexpectedly: emotions of reverence, awe, and intense fear would have been close to the surface. Undoubtedly part of this was a lack of understanding about why things happened. Nowadays we sit in air-conditioned buildings in front of computers eating food that we would not know how to cultivate, brought to our doorsteps by Supermarkets possibly from the other side of the world – who knows? We can hardly imagine what it was like then. We now seem to have explanations for everything from the origin of the universe to rainbows, from climate change to eye colour, from human behaviour to the date when our earth will be sucked into the Sun.

Our age has exorcised most of this spirit world; and probably for all-time. We might know better now but there are some losses. Look back at the ‘magic’ of plant common names: Love-lies-bleeding, Forget-me-not, Bleeding Heart, Shepherd’s Purse, Dogbane, Deadly Nightshade, Ladies Bedstraw, Eyebright, Vipers Bugloss, Buttered Haycocks, Bouncing Bet, Pukeweed, Cuddle-me Close, Old-man’s Beard – names that speak to us from a world that will never be recaptured. Yes, it was a different time with a different use of language. But plants are now a small and unimportant part of our lives when once they were all around us, providing our food and medicine – and many were sacred. Nowadays for most people, apart from the keen gardener, the lexicon of plant common names hardly extends beyond the common vegetables.

Christian scriptures, though including many references to plants and nature were in essence ‘other-worldly’, concerned with human conduct in relation to one-another, a single tripartite god, and an afterlife: it was a spiritual and moral code that, although it included plant references had little if anything to say ‘oficially’ about the physical relationship between humans and the Earth (see Christianity & the natural world). This contrasted with polytheistic Celtic and Nordic mythology which, though a spiritual explanation, was deeply grounded in the physical world of nature and the seasons.

Though today we have largely exorcised the spirits from mythology, its grand themes still grip our imagination. The domain of ‘spiritual’ has been largely subsumed under the category ‘mind’ and ‘creative imagination’: it has been treated the same way that Christianity has responded to the criticism of science by making it metaphorical or psycho-spiritual, a transition that possibly occurred in the Axial Age (800 to 200 BCE) in the Occident, China, India, and Persia with no clear lines of communication. Instead of spiritual beings existing outside the mind the source of spirituality was perceived as coming more from within – in Buddhism, Platonism, Taoism, Vedanta, even Gnosticism and Christianity.

Myths help a better understanding of the human psyche and what drives us all. This was well understood by Carl Jung in his analytical psychology. Today we can perhaps point to the work of evolutionary psychology as it attempts to explain the human mind in more evolutionary terms.

Science & myth

The urgency of the present moment brings with it the feeling that ‘now’ is more real, true, and authentic than the ‘nows’ of other times. We find it difficult to think of ourselves as existing in a certain time, at a certain place, under specific conditions. We know that the science of today will change as research proceeds. So, from the long-term point of view (the long duree) or that of another culture or, maybe, the Earth one thousand years from now . . . our present-day realities and truths will probably appear outmoded and constrained by space and time in just the same way as all those other belief-systems of the distant past that now seem so ‘out-of-date’ . . . so, are we inevitably just a product of our times. Is science just a creation myth like any other; just one more story?

This question is addressed in several articles on this web site (see, for example. worldviews) but for our purpose here we can note that ‘maps of reality’ are ‘never just true or false’ and science has long abandoned any claim to absolute truth. All sorts of explanations might serve many different purposes in a social context. The strength of scientific explanation is that it the world of competing ideas it has proved the best method of explaining the physical world that we know. Other forms of explanation might serve other purposes perfectly adequately.

Modern science is much more than just a workable description, it has proved itself through practical application. Its claims can be challenged by anyone with sufficient evidence. It has produced smartphones and genetic engineering, modern medicine and nuclear bombs; it has given us the power to manipulate the chemical components of our bodies that control our appearance, behaviour, and health; it has provided a convincing explanation of space and time.

Though scientific explanations are not ultimate truth, and they will change in the course of history, they are not the same kind of explanations as Greek myths, say the belief that a day is made possible when the god Apollo drives the Sun over the horizon. The claims of science are constantly passed through the most rigorous testing that we can apply.

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

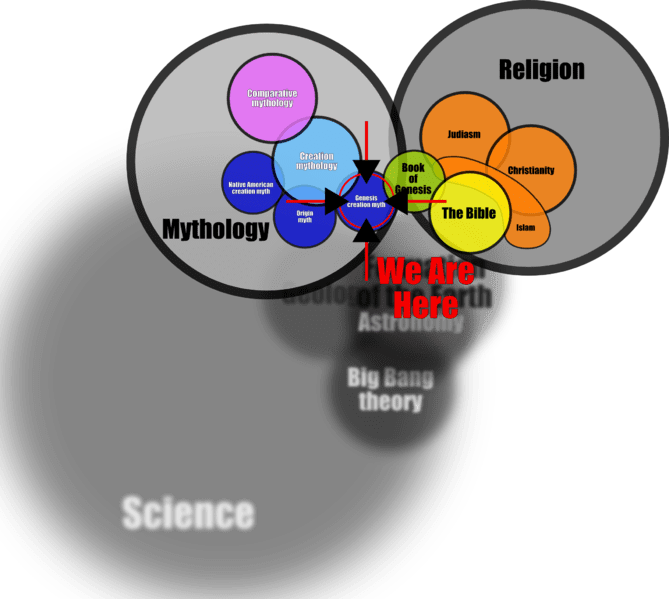

Internet interpretation of the world of myth and religion and today’s world

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons