Progress

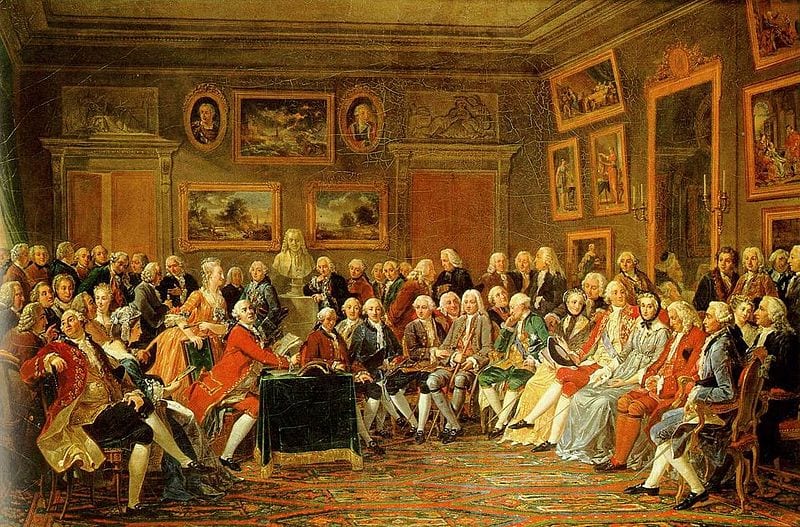

Gathering of distinguished guests in the drawing-room of French hostess Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin (1699-1777) who is seated on the right. There is a bust of Voltaire in the background. Painting by Lemonnier, 1812 now in the Musee National de Chateaux de Malmaison

The Enlightenment was a time when reason, science, and progress seemed inextricably linked. For a list of these distinguished French savants see the list of guests at the foot of page

Anon.

Anon.

For a broad historical and contextual account of progress see the article in Wikipedia.

It is intellectually unfashionable to assume that, collectively, humanity is making progress. Wherever we turn, it would seem, the news is bad. But ‘progress’, an abstract- sounding concept, is amenable to factual investigation. This article examines the empirical evidence for and against human progress – the grounds for pessimism or optimism – before discussing the path that the global community has set itself for the future.

Convergence

Each year the world’s nations become more interconnected and interdependent. Slowly and falteringly a collective vision for the future is coming into focus as individuals become more amenable to their role as global citizens. This is a careful political balancing process as the benefits of group membership are weighed against the needs of individual members. We feel secure with familiar groups we associate with from day to day and feel suspicious of outsiders. We have a circle of social comfort with increasing discomfort as we move outwards away from people we know . . . our partner, family, work colleagues, religious, ethnic and national groups etc.

World Citizen Badge

Sociologist Emile Durkheim explained clearly the way social groups need intellectual and emotional consensus if they are to maintain structural unity and how traditionally this social glue was provided by religion. Any vision for the future must give us a sense of advance and improvement, the feeling that by working together progress is being made. This does not mean that we must all be the same, or even that we should share the same beliefs and attitudes; it just requires negotiation and amicable settlement on points of common interest.

But how realistic is such a vision for the future? There are always set-backs in life for both individuals, societies, countries and institutions and, anyway, not everyone would agree that we are making progress right now. We might be making progress on some fronts and going backwards on others: every situation is different so we cannot generalize. Perhaps the whole idea of progress is a myth?

There is a simplistic view of history extolling the triumph of the West – it runs from Greece to Rome, to Christian Europe, to the Renaissance and Enlightenment, then the Industrial Revolution which, combined with liberal democracy brought us to western supremacy. Another linear view of history is to regard humanity as beginning with the misery and savagery of the hunter-gatherer, moving on to the life of backbreaking toil that is the lot of the farmer, then on to the materially satisfied modern businessman, industrialist, financier, bureaucrat, and technocrat. But have things really imporoved over time and are things really better now? What do we mean when we say that we are making progress?

Evidence for progress

Whether we are making progress or not depends, of course, on how we define ‘progress’. If we define progress with the synonyms ‘improvement’, ‘development’, and ‘advancement’ then little is gained since the request for justification can simply be repeated. The proof of the pudding is in the eating. We need examples of progress set out: only then we can say whether we agree or not.

Perhaps surprisingly there need be no ambiguity, philosophical vagueness, or unfathomable complexity in what we mean by ‘progress’. Progress can be measured empirically without becoming bogged down in semantics or philosophical and ideological contortions.

To get us warmed up consider the following statistics that can be obtained from sources like the UN, WHO, World Bank etc. They can, of course, be challenged in detail – but the progressive trends are self-evident and uncontroversial.[6]

Life-span – global average life-expectancy today is 70 years, 150 years ago it was 30 years.

Health – many pandemic diseases and plagues have been eradicated: smallpox, rinterpest, and possibly polio, guinea-worm, hookworm, malaria, measles, rubella, yaws. Infant mortality and maternal death in birth have been dramatically reduced.

Prosperity – in 2015 only 10% of the world was living in poverty with the sustainable development goal to eradicate poverty by 2030. 200 years ago global poverty was running at 85%

Peace – war between developed countries is now obsolescent, there has been none for 70 years, civil wars still occur but death rates have diminished over time.

Safety – rates of homicide are declining starting in 2000. In the 1990s there was a peak in USA and in 2015 this had halved, this being also true of other western nations

Freedom – though pockets of tyranny remain, overall the world has never been more democratic. Individual choice and freedom are at an all-time high

Education & literacy – in 1820 only 17% of the world had access to a basic education, today it is 82%.

Human rights – campaigns are now tackling child labour, female genital mutilation, capital punishment, human trafficking, violence against women, and gay rights – these are UN aspirational statements but this is often the first step in reduction. The following, once prevalent, have now ceased are been greatly reduced: human sacrifice, chattel slavery, burning heretics, torture and executions, public hangings, foot-binding, laughing at mental illness, and much more.

Gender equity – women world-wide are, in general, better-educated, marrying later, earning more, and in more positions of power and influence.

Intelligence – is increasing globally – see the Flynn Effect.

There appear to be many changes in our fundamental understanding of the world, all indicating progress:

Space – 2000 years ago there was no map of the world. Geographically at the time of the ancient Greeks it was thought that the Earth floated on a giant disk: we have now named all the land on Earth, we know what it consists of chemically, even in its centre, and can place it precisely within the solar system and web of galaxies that make up the universe, and we even know what the entire universe was like milliseconds after its birth at the Big Bang. Today we have a dtailed map of the universe.

Time – 2000 years ago we had no idea of how the Earth began or how it would end. We now have a scientifically-based estimate of the date of origin of the universe, its geology, how its organisms evolved, and approximately when and the possible ways in which the universe will end

Humans – 300 years ago it was largely believed that humans, and indeed all organisms, were placed on Earth by god in their final unchanging form: today we know that all life is derived from a common ancestor

Factual knowledge – factual knowledge is cumulative and as more facts accumulate so does the need to break up knowledge into subdisciplines. This has incerasingly occurred since the 15th century in th West

Matter – 2000 years ago knowledge of the structure of matter was purely speculative; today detailed scientific experimentation is performed on subatomic particles

Science and technology present us with the most glaring examples of change as progress. Indeed, this form of progress is accelerating fatser and faster. Some have forecast a critical mass of technological change leading to what has been called the techno-rapture which will occur in about 2035, a technological singularity as a fusion of machine intelligence, nanomachines capable of self-replication, biotechnology, and computer science, a change so dramatic that beyond this point the future becomes totally unpredictable.

Knowledge, as the communal accumulation of facts about the physical world, is cumulative. There might be ‘bad’ and ‘good’ knowledge but if knowledge itself is a measure of progress than we are progressing at a great rate. Not only are we constantly gathering more information we are also improving, expanding, and speeding up the ways in which we categorise and process that information in a constant exponential process of fine-tuning. This kind of progress is reflected in the steady growth in number, content, precision and general quality of the full range of academic disciplines. Insofar as the goal of progressive science is improved prediction, then this is increasing year on year.

Collectively these points make a compelling case for progress and they cut across a wide range of human activities. But maybe they are too scientifically- technologically- or knowledge-based. Perhaps we have not improved in a moral sense: we are not actually better people than our ancestors. But this too seems a flawed view.

Moral progress

A comprehensive study of violence in 2011 indicated that physical violence in its many forms (warfare, capital punishment, corporal punishment, child abuse, infanticide, torture, murder etc.) over the long term has steadily decreased from time when we were hunter-gatherers. There is not the space to defend this claim in detail. Suffice it to say that just a few hundred years ago in Europe a public disembowelling was family entertainment, torture was common practice, witches were burned to death at the stake, and there was constant bloody warfare over religious doctrine and dynastic succession. Only a generation or two ago women and black-skinned people were regarded as unquestionably inferior citizens. Few people would regard today’s opinions on such matters and today’s level of violence as a ‘change for the worse’ or ‘a matter of opinion’. Today we have a much more pluralist, tolerant, and inclusive attitude towards one-another than was evidet in the past.

It is as though the innate potential for violence that resides in us all as a consequence of our biological evolution has been progressiely overridden by the cultural evolution. But it is always present, ready to be roused.

morality also has an objective dimension that may have played out over time. Based on the golden rule of ‘do as you would be done by’ we understand the illogicality in most circumstances of demanding from others something that we would not be prepared to countenance ourselves and that, also in very general terms, there has been a move towards utilitarian goals, aiing towards the greatest happiness for the greatest number. When a natural disaster occurs we donate money in sympathy for those people in a foreign country that we have never seen. They suffer in the same way that we would in their circumstances. Culturally we can introduce modes of behaviour and policies that lead to this end. I refrain from killing other people because I would not like to be killed myself and because killing tends to cause grief and suffering, not because I fear divine retribution. This is a battle won by reason over passion. We have evolved physically by adapting to our physical environment: maybe we can evolve morally in the same way but by cultural evolution?

Another reason for this moral advance might relate to the enlarging of our sphere of moral concern in a utilitarian context, the desire to maximise human flourishing and the minimisation of harm. We can see this for example in the move from patriarchy to womens’ suffrage, the abolition of slavery, gay rights, and even the consideration of the well-being of other species. Where one time our allegiances were to our family and tribe they now extend to people across the world. As a world citizen much of the old prejudice will have been dissolved away. We are acknowledging that none of us, either individually or collectively, has any moral privilege over others.

We can actually see a hopeful trajectory of what might be termed a modern vision of moral improvement as this kind of morality spreads across the world, although acknowledging the constraints of human nature means there will always be a cap on what is possible.

Evidence against progress

Steven Pinker in his book Enlightenment Now (2018) suggests several reasons why any assumption of progress is likely to be challenged, most notably by intellectuals.

i) the availability heuristic (we focus on those generally recent events that are most vivid in recollection)

ii) we are naturally drawn to nostalgia

iii) we are subjected to the constant scaremongering news bias that sells papers

iv) we dread losses more than they look forward to gains

v) we avoid tempting fate

vi) because intellectuals confuse pessimism for profundity, assuming accounts of decline and doom are smarter than those of uplift and progress

We all grumble about the way things are right now – so there seems to be universal agreement that things could be better. The time when we were young and launching out in life always seems more rosy than today. For much of human history it appears that people, rather than looking forward to the creation of a bright future either accepted a drab uniformity of existence or looked back to a golden age in the past. Let’s take a quick walk through some of history’s major phases to assess their pro’s and con’s progress-wise.

Human nature

Why do we still make war? Doesn’t killing have the potential to lead into a cycle of violence? If we believe that killing is wrong, then how can we kill someone as a demonstration of justice being done? We might be forgiven for feeling cynical about the future given the past human record. And much of the disillusionment can be directed at human nature because it seems that we just dont learn – we cannot help ourselves.

If human nature doesn’t change then how is progress possible?

It turns out that human violence has actually diminished, on average, over the years.[7] We may not be able to change our biological nature but we can change our social institutions and customs to make such things less likely and to combat our inclinations. Though a level of disturbance seems inevitable, further improvement is clearly possible.

The Agricultural Revolution

Following the Agricultural Revolution, and in spite of the interruptions of war, disease, and local circumstance, the vast majority of people in the world (except for the small ruling elite), the peasants of Asia and Europe, for thousands of years led similar lives eking out a subsistence living on the land.

Society was structured in a traditionally accepted hierarchical way, and life’s fortunes would depend largely on the vagaries of the seasons. Though small changes would occur in daily routine and tools and techniques might change a little the agriculturist’s subsistence life had permanency, traditional conservatism, and a timeless and changeless quality.

The Classical world

We know that in the Greek world there existed at least two narratives of human history. For the Greek poet Hesiod history had been a process of decline. Humans originally existed in an ideal state of nature, a paradise or Eden, subsequent deterioration being a consequence of a corrupt relationship with nature (this is very similar to the Biblical story of Genesis). Life then became progressively preoccupied with toil and misfortune. This account was also reminiscent of a general Near-eastern belief in four declining eras, starting with a golden age of plenty and followed by the silver, bronze and iron ages. Culture was not something to praise, on the contrary it was a mark of human degeneration.

Hesiod’s utopian and romanticised theory of the past is outlined in his Works and Days (c. 750 BCE) in which ‘The first humans were a golden race who lived in harmony with one-another in perfect peace and leisure in an eternal spring, and were beloved of the gods‘. When all have gained wisdom cities themselves will be unnecessary and laws will become redundant as all people will naturally cultivate justice.[4] His own age he saw as ravaged by warfare, voyaging for unnecessary luxuries, and a drowning in abundance as gold was chased and money invented. Cities were not the pinnacle of human achievement but imperfect places where people sought wealth and power until, exhausted by strife and motivated by fear, they had ‘agreed to be bound by restrictive laws and coercive justice‘ and, as Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius (99-55 BCE) later added to this view, ‘hence fear of punishments taint the prizes of life‘.[4]

In contrast, philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and Protagoras maintained that through culture humans were set on a path of progress, escaping from an original violent and sinful condition that was at the mercy of nature and moving into a state of communal living, or civilization, where justice could prevail and where technology and a moral life became possible. Later indignant Roman voices, like that of Seneca and Pliny the Elder, railed against the extravagances of luxury, the self-indulgent Roman aristocracy, and human folly when dealing with nature.

These two themes – ancient humans as either innocents or violent savages, and human culture as either progress or corruption, have echoed through history to the present day.

Even the creators of civilizations could be backward-looking.

‘The Romans were amazed at stories of what Archimedes (287-212 BCE) had been able to do … fifteenth century Italian architects explored the ruined buildings of Ancient Rome convinced they were studying a far more advanced civilisation than their own. No one imagined a day when the history of humanity could be conceived as a history of progress, yet barely three centuries later, in the middle of the eighteenth century, progress had come to seem so inevitable that it was read backwards into the whole of previous history.’[5]

Christianity & the Middle Ages

Christian theology emphasised sinful humanity and its Fall from God’s grace. Medieval European learning looked back to the Bible and its theological interpretation or to the philosophical texts recovered from the Greco-Roman world. In both cases deference was to the past. Philosophers and scholastics looked back to the brilliance of Plato and Aristotle and church academics searched for truths, enlightenment, and certainty in theology and the Bible.

Renaissance & Enlightenment

Certainly the advent of modernity, the revival of ancient learning beginning in about the fourteenth century, gathering momentum in southern Europe and spreading gradually to the north-west, provided the basis for a new outlook on life. This was accompanied by a Scientific Revolution that reconfigured the place of humanity in the universe. As the grip of religious dogma and occult practices loosened many would see this point in history as the time of greatest change in attitudes, that the intellectual and scientific reawakening of seventeenth and eighteenth century Europe gave us the very sense of progress – the feeling that there was potential in the future rather than wisdom in the past. Optimism for the future reached its height with the confidence and trust in reason and science that marks the Age of Enlightenment. This was a rare period of hope and expectation as exemplified in the writing of French philosophe the Marquis de Condorcet (1743-1794) as follows:

The perfectibility of man is truly indefinite; and that the progress of this perfectibility, from now onwards independent of any power that might wish to halt it, has no limit than the duration of the globe upon which nature has cast us … this progress … will never be reversed as long as the earth occupies its present place in the system of the universe.[1]

Condorcet’s Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Spirit (1795) was one of the most influential documents of the Enlightenment and possibly the most persuasive articulation of the idea of progress ever written, proposing that an increase in knowledge of the natural and social sciences must promote justice, individual freedom, material well-being, and compassion – that the past reveals a progressive development of human potential – that increased knowledge in natural science must lead to moral and political improvement – and that social aberrations are the result of ignorance and error rather than the inevitable consequences of human nature. He personally promoted free and egalitarian public education, equal rights for women, equal rights for all races, liberal economics, and constitutional government.

Industrial Revolution

A major change in material conditions arrived with the Industrial Revolution which left the world with many material benefits. But again there was another side to this story. Machinery and coal had brought grit, factories, grime, urban crime, depressing and smoky city landscapes and soulless toil. Certainly there was a sector of society that had benefitted but life was not so good for factory workers, peasants, colonial subjects, plantation workers, and especially native peoples displaced from their homelands.

Enlightenment optimism which pinned its hopes on the progress of humanity through reason and science received a virtually unrecoverable blow as Europe’s supposedly enlightened humanitarian community engaged in two of history’s bloodiest wars at the cost of over 70 million lives leaving only a pervasive sense of cynical disillusionment and despair. The wonders of technology that produced the car, aeroplane, telephone, radio, light bulb, gene technology and computers had also created tanks, missiles, mustard gas, thalidomide, DDT, radiation, and nuclear bombs.

For some time the possibility of global destruction by nuclear warfare was a real possibility. Can technological progress could lead to large-scale destruction as seen in World War I and World War II, and run counter to the basic premise of the Idea of Progress?

Is science all good?

Science and technology have no doubt improved the material conditions of existence but the assumption that science and technology are always a force for good does not hold up. With the discovery of the atomic structure of matter came the threat of nuclear holocaust. Our capacity to create synthetic substances has produced contamination like that of DDT in the 1960s. Our highly energised fossil-fuelled post-industrial society can now be seen as a major contributing factor to the climate change that threatens everyone. The science and technology that has underpinned the growth in both population and economy has also made more devastating the environmental degradation that follows intensive resource extraction. So, there is no shortage of plausible apocalyptic scenarios hanging over our heads, including the spectres of nuclear warfare, terrorism, climate change, and environmental collapse.

Is it then the scientific revolution that defines our age, the age of modernity – the time when Aristotle’s deductive logic would be superseded by the stronger paradigm of experiment, observation, and calculation?

Progress & forward momentum

Mainly because of the way technology becomes increasingly complex and sophisticated from year to year, today we have a sense of steady advance and anticipation of technological improvement in the future. But this is not an inevitable outlook on life. Many people through history have regarded life as presenting relatively little overall change. Existence like that of Australian Aboriginals living for tens of millennia as hunter-gatherers are sometimes spoken of as living in cyclical time. Just as an individual is born, grows, flourishes, declines and dies, the same can be said of the cyclical repetition of seasons, societies, and civilizations.

Without a doubt these views were all shaken by the European Renaissance, Enlightenment, and the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions which collectively we refer to as modernity. It included new geographic discoveries for Europeans and new ideas about politics , social organisation, technology and science, all combined with a rapid growth in in commerce and industry, a transfer of people and finance from the country and the land to towns and cities. As the material benefits of the Industrial Revolution flowed down the social hierarchy belief in a better future increased.

The world known in the first half of the fifteenth century was effectively the same world known to any Roman intellectual using Ptolemy’s 1490 map of the world published in his Geography. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it was the Scientific Revolution that ensured progress be assumed an inevitable part of daily life – that it was responsible for the Industrial Revolution and the technology that followed.

In attempting to draw all this together it will help to distinguish two senses in which we think of progress which we can call Progress 1 and Progress 2. Progress 1 relates to an increase or advance in knowledge, efficiency, material, or intellectual benefit: Progress 2 relates to an outlook for the future with progress expecting optimistic and beneficial outcomes.

Political progress

It is difficult to claim political progress without some uncontentious measure since politics will seem to be making progress provided what we as individuals subjectively wish for is increasing.

Insofar as liberal democracies result in relatively equitable, non-violent, tolerant, multicultural communities with a high degree of individual freedom then we can surely regard this as progress over violent and self-seeking intolerant dictatorships and tyrannies.

Australian settlement

Certainly Australia’s European settlers were convinced that agriculture and industry were a civilised advance on a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and that agriculture was ripe for modernisation so that surplus could replace subsistence: wasteland could be appropriated and turned over to cultivation for the benefit of all so that improvement was manifest, not just in the mind. ‘Improvement’ was the preferred word for man’s selective breeding of new crops and domesticated animals. White Australian settlers regarded themselves as a superior race, the Aboriginals being backward and in need civilizing improvement to ring them up to an acceptable standard of living.

Self-improvement – human nature

Of special interest was the idea of improving human nature. Given the fresh circumstance of settlement and the possibility of reward for honest toil convicts could be converted from criminals to useful citizens. Indeed Australia’s first generation, known as ‘currency lads and lasses’, were described by Commissioner Bigge as taller, fairer, stronger and healthier than the free settlers, indeed taller than their British counterparts, and with a distinct way of talking. They were generally industrious, free of criminality and more than 80 per cent of the men and 75 per cent of wrote their own name on the marriage register. Boys enjoyed sport especially foot races and ‘knuckle’ boxing and ‘afford a fair hope of great and progressive improvement in the population of the Colony and its Characters’[2] This suggested the tantalising possibility of human perfection, a transcendence of original sin and our broken human nature. The objective of moral progress was loosely described in terms of industry (hard work), sobriety (clearly alcohol was a major factor), and prosperity. Above all it was agriculture that was seen as the supreme mode of moral improvement, for both convict and Aboriginal. Improvement of the moral character of the natives was to be a major theme of early settlement along with the suggestion that they could be refashioned when separated from their families – a view that became state policy.[3]

It is this aspect of the Enlightenment project that makes us uncomfortable today, the contrast in outlooks of European and First Australian: for the European the overwhelming confidence in the rightness of change, a disrespect for the land, its rhythms and history, and desire to dominate and subdue for purely human ends, introduction of alien plants and animals, the individualistic formation of all kinds of boundaries, both literal and metaphorical so alien to Aboriginal communality, and an overwhelming preoccupation with economic growth through a complex division of labour.

Karl Marx characterised societal history in progressive evolutionary terms, from tribal to feudal to capitalist to socialist while Malthus pointed out that human populations, like those of other organisms, grow to outstrip the food supply after which they are inevitably cut down by famine and disease until an approximate food equilibrium is reached once again. In spite of the two World Wars of the 20th century with the paradigm of technological change as advance almost any social change is regarded in the same way.

The 18th century Enlightenment carried the torch of moral improvement and progress. This was an intellectual revolution of hope, direction and a feeling that humanity was maybe, at long last, heading in a positive direction. Politically the new constitutions were trying to write the potential tyranny of ruling dynasties and monarchies. Science was opening up the secrets of the natural world on a global scale and technology was giving humans unimagined and unprecedented improvements in communications, manufacturing, trade and much more.

But it seems that all this went sour. The hope of the, the American Revolution led to Civil War, the French Revolution ended in the slaughter of the Terror with the Russian Revolution following a similar path seemingly ending in the atrocities of Stalin’s regime. The tyranny of kings and queens was replaced by the tyranny of the ‘people’ as manifested by their leaders like Mao Tse Tung and Pol Pot. The Industrial Revolution brought dirt, grime, factories and wage slavery.

If the lessons of history cannot be learned then are we condemned to continually repeat the errors of the past?

Measuring progress

Many of the items of Program 1 can be simply measured but what do we do when as individuals and groups we aspire to different things, and when we have different visions for desirable futures. Given such subjectivity it would appear likely that we fail at the first hurdle of establishing common goals.

Quality of life. Sustainabiity.

Economic growth

Poverty, and even simplicity, can lead to a lack of flexibility and choice. Widespread poverty is bad for the environment.

Our modern interconnected and globalised world has been constructed in large part on the mutual material benefits of commerce and trade. Social benefits of not only material comforts and infrastructure but health systems and even individual freedoms have flowed into societies built on thriving economies. If we assume that economic flourishing has opened up options to people once restricted in their life-choices then societal progress can be defined as the collective direction of peoples’ choices, what has been termed – revealed preference.

While one of today’s greatest global problems is the alleviation of poverty, within the developed world it is now clear that the values of the market are not sufficient in themselves. We must measure our lives in more ways than just the Gross National Product.

Happiness & well-being

Perhaps the strongest argument against progress is that it has not increased our happiness. And insofar as happiness underlies all that we do, and since it has not increased with progress, then progress counts for nothing. This has given rise to a search for uncontroversial values common to humanity as a whole; values that we can all accept, measure, and therefore find practical in our daily lives. These values have centred on the ideas of happiness and human well-being.

While at first glance ‘happiness’ and ‘human well-being’ look like toothless motherhood statements they are rapidly becoming the foundations of a universal globalised objective ethic giving substance to the idea of progress and its measurement. Far from being imprecise and obscure concepts the United Nations has introduced whole programs based on their strength.

With human well-being (sustainability progress) as a universal moral baseline we are making use of a broad contextual base that allows us to move forward, to progress in relation to the question ‘how can we make the world a better place?’ The pursuit of sustainability progress entailing harmonious coexistence with the community of life and future generations as an international policy provides a universal foundation and goal among the many competing value systems –though hardly different in many way from utilitarianism which seeks the common good, sustainability is a more transparent concept attached to an international program and policies for the future. As a moral goal sustainability progress is not subjective, there are better and worse ways of achieving it in the material world.

Massive historical average decrease in human violence, lower infant mortality, longer life expectancy, increased gender, racial and religious equality, few would doubt our overall moral improvement. However, as discussed elsewhere, such judgments can only be made using a baseline assumption that human flourishing or well-being is a given, and the possible formation of the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement does not render this invalid. Almost all humans display a strong will to live and flourish as a defining part of their nature as living organisms.[p. 48]

Measurement

We can, on the one hand, think of progress in a very general way through our attitudes and beliefs towards such wide and abstract categories as humanity, factual knowledge, space, time, matter, value, spirit, and mind and, on the other hand, practical day-to-day matters like life expectancy broad categories like life-expectancy ……

Now, human progress is increasingly being understood as much more complex than this, including the values that underpin our life together, goals that relate to our wellbeing as individuals and as communities, and the effective and sustainable use of our resources for the wellbeing of future generations.

Based on the idea of an ongoing conversation about what kind of society we want to be, ANDI will develop clear, ongoing measures of our progress towards that vision: an Australian National Development Index.

Evolution by natural selection made progress a necessary law of nature and gave the doctrine its first scientific formulation, not a advancement towards a single goal but, by adaptation, to goals that were appropriate for the particular circumstances. The increase in organic complexity has been paralleled by an increase in social complexity of globalisation.

What can upset this trajectory?

Catastrophic climate change and nuclear war – not inevitable. Global Zero movement for the elimination of all nuclear weapons.

Why is this counter to the perceptions of many people?

Cognitive bias that ‘availability heuristic’ – sense of danger is not based on objective facts. News is about what happens not what does not happen.

We confuse changes in ourselves with changes in society.

We are all social critics and pessimists get greater respect than optimists.

Why has it happened?

Rise of institutions that support it – government is a disinterested third party better than individuals, an evolving global leviathan of UN evolving on average improving. Since 1945 very little conquest of territory. WHO set best-practices etc. Improving markets China and India switching to market economies. Advancement of science with public health.

Broadening the circle of justification and concern rather than following tradition, tribalism, conformity, gay rights have almost totally collapsed. Making your case beyond your own interest group. Observing facts, reason, life, health, and happiness are common ground and universal values rather than local ones.

‘If it bleeds it leads’ but positive too if rapid news and very difficult to keep a secret. Sexual abuse, bullying, has become widely publicised and this is an advance – both cause and consequence of our expanding cycle. We can quickly regress to evolved human reactions that are easily moralised. Absolute terms things getting better but inequities cause resentment but extreme poverty is a first concern.

Individual events can be misleading of general trends. Pessimism can turn into fatalism and revolutionary fervour and desperate actions.

Religion has, in general, followed the tide of humanism. The Church now accepts evolution and other scientific discoveries etc.

Commentary & sustainability analysis

A vision for the future

The liberal democratic model of sceptical, humanistic tolerance coupled with science and reason seems to be the nearest we know to a stable system. It has come at a great cost.

Science

Technology – the technorapture

Economic growth

Credit like that of joint stock companies was loaned in the belief and trust that the future would bring real rewards. So together with technological progress came a new confidence in credit (that there would be good returns on loaned money) and this launched a phase of unprecedented economic growth under capitalism.

Optimism & pessimism

Optimism breeds confidence in the future: economically this means the willingness to allow credit and to invest in the future. Pessimism leads to either hoarding or hysterical partying. Of the 15,000 to 20,000 languages once spoken the majority have been lost and the pace of extinction is increasing.

Effects of time – long-term, short-term

Pace-layering fashion short, commerce longer, infrastructure longer, culture longer, nature longer. Tendency towards short-termism (next quarter or next election cycle). A responsibility record considers the long-term consequences of particular actions and policies and places them on the official record for constant review.p. 98 Long now. Like drug addicts we discount the future by taking maximum advantage of the present. 10,000 years is 400 generations (with 25 years a generation). Big data and data mining. Rapid change means data storage needs constant monitoring.

Darwinian social evolution

We can add, for interest’s sake, the idea of biological or evolutionary progress.

The industrial revolution, then, was no more than a consequence of this more fundamental shift in culture and, contrary to the skeptical Romantic outlook on life (with its distaste for engines, factories, steam trains, genetic engineering, and disrespect for nature) the scientific revolution was decidedly a change for the better.(1)

Complexity

Civilizations now have strong and flexible structures that are resilient, that can adjust to and sometimes absorb shock. Knowledge has been fragmented into innumerable small specialities. More and more about less and less.

Relativism & postmodernism

Relativism, the argument that there is no such thing as progress, has come to command widespread acceptance, irrespective of whether the progress in question is being sought in political, sociological, scientific or other fields of endeavour. To most scientists this thesis is at best puzzling, and at worst rubbish. We see every day that progress is palpable, even if it is not linear or problem-free. Wootton will earn the affection of scientists by recognising and accepting this, and he makes a convincing case that we must steer a course between hard relativism and naive realism. He may, however, need to steel himself against the anger of his historian peers.

Media Gallery

Steven Pinker On Enlightenment Now: Is The World Getting Better Or Worse?

Center for Inquiry – 2019 – 42:16

Is the world getting better or worse? A look at the numbers | Steven Pinker

TED – 2018 – 18:32

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . 1 August 2023

Gathering of distinguished guests in the drawing-room of French hostess Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin (1699-1777) who is seated on the right

There is a bust of Voltaire in the background.

This 1812 painting by Anicet Lemonnier (1743-1824) is now in the Chateaux de Malmaison

Back row, left to right: Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gresset, Pierre de Marivaux, Jean-François Marmontel, Joseph-Marie Vien, Antoine Léonard Thomas, Charles Marie de La Condamine, Guillaume Thomas François Raynal, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jean-Philippe Rameau, La Clairon, Charles-Jean-François Hénault, Étienne François, duc de Choiseul, a bust of Voltaire, Charles-Augustin de Ferriol d’Argental, Jean François de Saint-Lambert, Edmé Bouchardon, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, Anne Claude de Caylus, Fortunato Felice, François Quesnay, Denis Diderot, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune, Chrétien Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, Henri François d’Aguesseau, Alexis Clairaut

Front row, right to left: Montesquieu, Sophie d’Houdetot, Claude Joseph Vernet, Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle, Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin, Louis François, Prince of Conti, Duchesse d’Anville, Philippe Jules François Mancini, François-Joachim de Pierre de Bernis, Claude Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon, Alexis Piron, Charles Pinot Duclos, Claude-Adrien Helvétius, Charles-André van Loo, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, Lekain at the desk reading aloud, Jeanne Julie Éléonore de Lespinasse, Anne-Marie du Boccage, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, Françoise de Graffigny, Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Bernard de Jussieu, Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons