Representation

Principle of Reality – We cannot step outside ourselves to survey the world ‘as it really is’. This would be like a ‘God’s eye view’, or seeing things ‘from the point of view of the universe’ . . . a view from no time, no place, and no perspective. There is no such vantage point for humans.

Science provides us with a progressively more efficient and effective interpretation of the world as it exists both inside and outside our minds: but a ‘perspectiveless’ account of reality is not possible.

Pragmatic metaphysics

Hierarchical levels of organization

Scales of understanding: frames of explanatory reference: domains of knowledge: cognitive categories

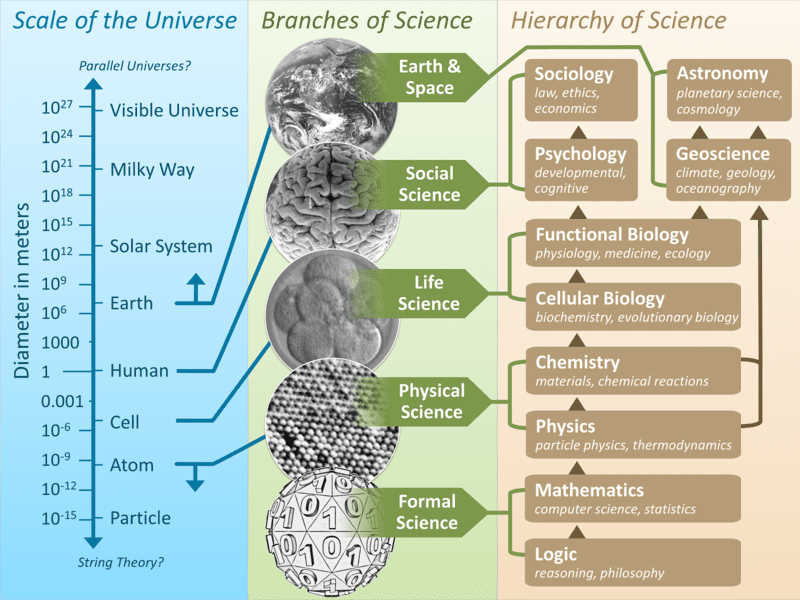

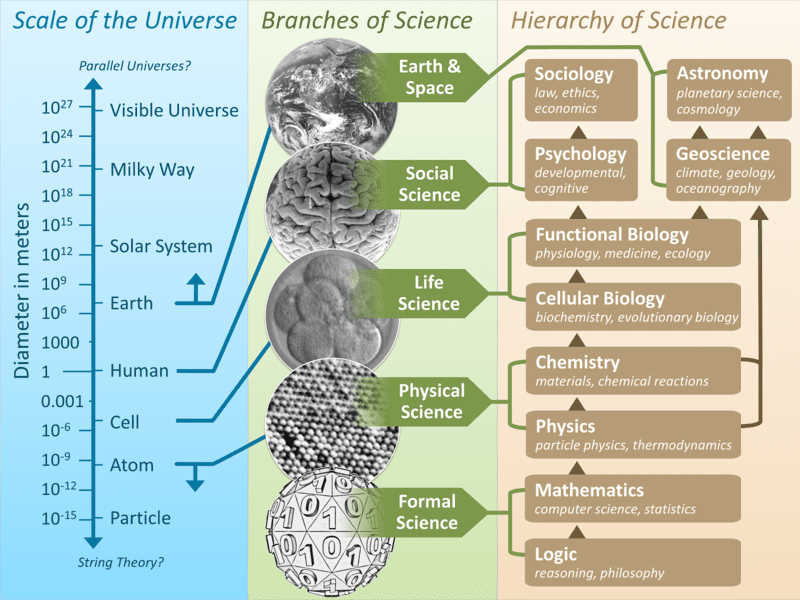

A diagram indicating some aspects of science that are generally ignored:

Its goal to extend the human senses

Its organization into frames of explanation and understanding

The refining of categories used for explanation.

Cumulative collective learning

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Introduction – Representation

Scientific research proceeds on the assumption that there is a world outside our minds, an external world of objects and events that we can investigate in a scientific way: a world that persists after we die.

This view contrasts with various philosophies and perspectives that emphasize inner subjectivity – that the external world is unknowable, or that it is in some sense constructed by our minds. While philosophers wrestle with this subjectivity scientists proceed, business as usual, secure in the knowledge that their discipline has amply demonstrated its credentials through its predictivity, explanatory power, and application to technology.

Even so, it is instructive for scientists to occasionally visit philosophical questions as an antidote to scientific complacency, so please read the article Immanuel Kant which helps set the scene for the article you are reading now.

The article on Kant’s philosophy introduced several key issues in science: the role of the mind in understanding and explanation, especially as it relates to the way we process empirical evidence and questions about the degree of confidence we can have in scientific knowledge. Kant also raises the question as to whether an ultimate or absolute state of knowledge (what we might term ‘reality’) is possible, whether it makes sense to speak of scientific truth.

This article extends themes raised in the article on Kant, exploring the relationship between the world of our direct experience, which is essentially the world of common sense (referred to here as the manifest image (direct realism), and the world as revealed to us by science as the scientific image. Does the scientific world present us with ‘reality’ leaving our common-sense world one of illusion? This is one of the major tasks of philosophy today, to ‘hold our hands’ as we try to reconcile these two vastly different ways of understanding and explaining the world.

As usual, important claims made in this article are stated as principles for you to challenge.

Representation

The only way that we can access the external world is through the filter of our minds whose capacities we have extended using the technologies made possible by science (like microscopes, telescopes, particle accelerators, and computers). This knowledge is then shared between us through the miracle of sound and symbol, the spoken, written, printed, and digital languages.

The brain

Scientists, though renowned for their objectivity, can easily forget that science is a body of theory and explanation, not ‘reality itself”. A scientific fact is always open to question, it is strongly corroborated belief, not the world ‘as it actually is’.

Principle 1 – Scientific facts are always open to question: they are strongly corroborated belief, not the world as it actually is (which we can never know)

The task of science is to not only understand and explain the world outside our minds but to also understand the operations of our brains themselves. Since all knowledge is processed through our minds (as brains) then they must be regarded as a computation devices with limitations, being potential sources of error and uncertainty.

The human umwelt

Without doubt, the way we humans frame the world is, at least in part, a consequence of our innate mental processing which, in turn, is a consequence of our uniquely human evolutionary history.

Baltic German biologist Jacob von Uexkull (1864 – 1944) named the environment of significance to any organism (those factors important for its survival and wellbeing) its umwelt.[1] This is, as it were, the organism’s species-specific frame of reference, the world in which it exists and acts as a subject responding to sensory data . . . its ‘reality’. This contrasts with the same environment as perceived and understood by a human.

Needless to say, different species have different umwelten, even though they share the same environment . . . they have different ‘realities’. For example, a tree uses light for photosynthesis, while humans use light to see.

Much of our cognitive activity is taxonomy. Without the constant ranking and classification of the objects of our mental life it would not be possible to operate in the world. The world is a meaningful place only because our minds are constantly ordering the multitudes of images, ideas, emotions, sensations and other representations that are passing through our brains. Much of this goes on unconsciously as innate computation (see mental processing) while some requires the conscious effort of reasoning.

Mental objects form a complex system of parts and wholes that makes up the web of mentally connected categories that are often ranked into an order of priority to serve our conscious and unconscious needs and intentions at any given time.

As an innate faculty mental processing is also, of necessity, part of the human experiential umwelt[1] – our reality – the way that we humans share a uniquely human collective experience of the world. This is part of our human nature.

Language

Science is also a social activity within a scientific community which advances by sharing knowledge through the medium of language (including the symbolic languages of mathematics and logic), so the words we use to communicate scientific ideas need to be expressed as clearly and precisely as possible. Scientific language aspires to be objective and value-neutral, but this is an aspiration that is difficult to achieve. Scientific papers contain more evaluations and imprecision than most scientists would care to admit. Among the potential sources of error and ambiguity transmitted in scientific language are the use of metaphor (‘as if’ language), anaphor (the way the meaning of terms is not necessarily distinct but linked to others in a web of association), and polysemy (the same word having different senses or meanings).

So how do we make judgements about the world that exists outside our bodies? Until quite recent times the mind was regarded as an unfathomable source of subjective uncertainty. However, the study of perception and cognition is now a well-established part of modern science that has taken over a role formerly occupied by religion and philosophy.

The Manifest Image and the Scientific Image

From its very beginnings philosophy has been concerned with the distinction between appearance and reality and this remains the source of much puzzlement and intellectual confusion. Certainly one major task of philosophy is to help us steer a course through the rough waters between the world as presented to us by science and the world of common sense.

On the one hand – is the world really just subatomic particles? Do colours really exist? Is matter solid or is it mostly space . . . and do space and time really exist independently of one-another? Do we really have free will? On the other hand – is science really just a glorified myth, yet another social construct, a convenient narrative appropriate for its time and place in history but that is all, ultimately destined for the cultural bin of abandoned ideologies and intentions that is the history of ideas?

American philosopher Wilfrid Sellars (1912-1989) suggested two different but useful ways of thinking about ‘reality’: two realities so to speak. First, there is the reality of our everyday impressions of the world, the common-sense world of direct experience as presented to us by our biologically evolved and species-specific sensory apparatus. This Sellars called the ‘manifest image’. Our other major way of understanding reality comes to us from the worldview presented to us by science, a worldview of extended senses attempting to experience the external world that lies beyond the world as presented to us by our biologically-given experience. This Sellars called the ‘scientific image‘.[4]

Sellars referred to our uniquely human experience of the world, the world as presented to us by our species-specific human senses and brains, as the ‘manifest image’. This is the world of everyday experience, the world of common sense. But Sellars noted that we humans are special because we have exceptional brainpower that allows us to explore beyond our immediate experience to gain a less anthropocentric, less ‘human-filtered’, impression of the external world. This minimally anthropocentric account of the external world he calls the ‘scientific image’.

The Manifest Image

The world of our everyday experience, the ‘manifest image’, comes to us as a product of our human evolutionary history, as a result of the interaction that occurred between our ancestors in their environments of evolutionary adaptation. The inherited characteristics of our perception and cognition, we must assume, are those features that have enhanced the survival and reproduction of our species. Our innate cognitive abilities are ones that have ‘worked’ for us as humans in the past.

The world as we know it, the manifest image, is a human ‘user-friendly’ representation, our species-specific umwelt.

We know that there are ways of experiencing the world that are different from ours. What must it be like for a herring, amoeba, or even a dog. Think of the effects of scale by imagining a human consciousness occupying a giant nebula or an electron. The diversity of the community of life demonstrates the many different organic ‘solutions’ that have arisen in relation to the variety of environments. Just as there are many physical solutions to similar environmental problems so there are many ways for sentient organisms to experience the world. Each species of sentient organism experiences the same external world in a species-specific way depending on the structure of its evolved sensory apparatus and therefore its mode of perception and cognition. So each sentient species has its own manifest reality. Humans too have a species-specific reality as represented by their evolved sensory apparatus, perception and cognition. They too have a manifest image of the world.

Principle 2 – Each sentient species of organism experiences the external world in its own particular way as determined by its uniquely evolved species-specific sense organs

The world I experience is ‘everything’ to me, it is my ‘reality’. I am unaware of the broad range of sounds and smells that a dog can experience – because I don’t hear or smell them. So, I might assume that what I experience is all there is: that I experience reality in totality.

But just as our bodies can only run so fast and jump so high, so our minds are subject to many cognitive limitations. We will each differ slightly in our cognitive abilities but, if healthy, share broadly the same experiences as our fellow humans because of the genetic makeup we share as part of our common evolutionary history.

As a result of our expanding scientific worldview we have come to realize that the world of everyday experience is a very restricted one so it is worthwhile listing a few of our limitations:

a) Our world is four dimensional though perceived in two dimensions on our retinas

b) We only see (visible) light to wavelengths about 390-700 nm (frequency 430-790 THz), the wavelengths differentiated into colours

c) Our audible range of sound waves lies between about 20 Hz to 20 kHz

d) We have the ability to hold only about seven digits in working memory and to perform only elementary computations. I cannot compute numbers as quickly as the machine in front of me

e) We have a psychological sense of ‘now’ that lasts about 2-3 seconds

f) Our sense of the scale of everything is a human-based sense of scale

A benign illusion?

Our common sense suggests that we perceive the world immediately and directly as it ‘actually is’. The external world, the world outside our minds, is a world of colours, sounds, tastes, smells, trees, roads, buildings, people, and so on. But with only a little reflection it is clear that what we experience is a consequence of our mental structuring and the way we process sensory information: we experience the world in a uniquely human way. Does this mean that the world of our everyday experience is illusory?

Is colour an illusion because science tells us that what we see as colour is waves of particular frequencies? Are living organisms an illusion because we can explain them in terms of their underlying physico-chemical constituents? Is money (not the coins and notes) an illusion? Are abstract objects (a promise, information, possibilities, my physical centre of gravity, words) an illusion?

We might be tempted to conclude, after learning the physics of light, that colour is an illusion. Our direct experience (the manifest image) is not mistaken or illusory but it is only a partial representation that we have extended scientifically (the scientific image).

The list of scientific findings that run counter to our common-sense manifest image is a long one. The manifest image presents us with substances as solid objects: the scientific image as shown by instruments that peer into matter as the minutest constituents tells us that it is mostly space, that what we once thought were solid particles are better understood as small vibrations in quantum fields; that the external world is best represented as waves and force fields or interacting vibrating fields; that our sense of gravity is the curvature of spacetime; that light and sound have speed limits; that our human visual range extends from about 1 mm to about 1 km while scientific instruments extend our vision across an observable universe of 93 billion light-years; that our sense of colour explores just a minute fraction of the possible range of wavelengths as a visible spectrum, and so on.

Is it the manifest image that is ‘real’ or is it the ‘scientific image’? To what extent do our minds add colour to wavelength, smell to molecular structure, consciousness to experience, structure to matter, cause to conjunction, free will to determinism? The manifest image is clearly ‘real’, but what we have learned from the scientific image is that the manifest image is only a partial view of ‘reality’, the scientific image giving us a different interpretation of reality.

For a more detailed account of philosopher Wilfred Sellars’ Manifest and Scientific Image, see the presentation by philosopher Dan Dennett here.

Part of our biological make-up is to classify the objects of our experience into groups depending on the purpose for which they for which the grouping is needed. In order to act we then rank (prioritize) these objects. In other words the objects that populate our experience relate to the purposes (functions) we desire.

Insofar as these objects have a role to play in our lives we can say that they exist. But are some benign illusions? Is free-will a benign illusion?

A computer has a visual interface with folders, files, and a background as a user-friendly and simplified representation of what is going on in the computer. Is the manifest image like this, with a complex underlying ‘reality’? This seems undeniable but does this make the interface unreal or an illusion?

To say that ‘everything’ in the world is everything that we can speak of and imagine is a highly anthropocentric viewpoint. We don’t know what we don’t know. We must conclude that the world contains many things that we have never thought of, spoken about, or imagined. And, given our biology, some of these we may never know. What do I know about the experiences of a herring? We must also conclude that natural selection will have emphasized those aspects of our sensory apparatus that are important for our reproduction and survival and that our intuitive physics is populated by Kantian Categories.

The Scientific Image

Science can be regarded as the attempt to overcome the biological limitations of our cognition, it tries to extend our biologically given ‘reality’ or umwelt by adjusting for the human-centredness of our world view – our natural intuitions, biases, and the limitations of our species-specific percepts and concepts. We have overcome our biologically given human limitations in many ways: by devising: microscopes and telescopes, electron microscopes and radio-telescopes, particle accelerators, gene splicers, X-ray machines, radar, spectroscopy, computers. All these technological devices are, as it were, add-ons to our biologically given sense organs and therefore extending the range and therefore the scale of our experience of the external world. We can detect radiation remaining from the Big Bang at the beginning of the universe; we have discovered that the edge of the observable universe lies about 46–47 billion light-years away; we have penetrated into the minutest particles of matter way beyond the range of the naked eye; we believe that the attractive force between bodies, once known as gravity, is due to the curvature of space-time; we have found that the inheritance of biological characteristics is a consequence of a protein-generating ‘code’ found in the chemical structures of every living cell. The increase in our understanding of the physical world that lies beyond our biologically given senses has been astounding. We can detect an electromagnetic spectrum of wavelengths from thousands of kilometers down to a fraction of the size of an atom.

This artificial extension of our biologically given senses was made possible by our extraordinary brainpower and it has turned us into super-organisms.

But it is not just technology that has extended our capacity to understand the world outside our minds. We have devised mental ‘tools’ to improve this understanding, one of these being mathematics.

Dogs can hear sounds beyond the human range of hearing and they also have a far more acute sense of smell than us. Bats use echolocation to determine their position in relation to other objects (including other flying bats and their flying prey!) to an extraordinary degree of precision. Each animal therefore has its own experiential world and also, in this sense, its own reality. When viewed in this light human reality is just one of the many possible experiential realities that exist among sentient animals. Does this mean that reality, what we make of the external world, is just relative to what kind of organisms you are – the reality of the bat is different from the reality of a dog, which is different from your reality, which is different from my reality? Though there is a sense in which this is clearly correct, it is important to recognize that it is not the external world that is different for each organism, the external world is the same for all organisms, it is only the experience of that external world, the sensory interpretation of the world, that is different.

If humans have an evolutionary advantage over other organisms it appears to have arisen not through our sensory apparatus but through the brain computing capacity enabling a form of comprehension that makes the ‘scientific image’ possible. It includes:

1. Imagination; memory (facilitating narrative and meaning); contemplation of past and future; thinking of objects that are distant from us; consideration of counterfactuals; a sense of self; and abstract ideas. Non-human sentient animals are focused far more on the present moment

2. The ability to create not only spoken and written languages but also symbolic languages (e.g. logic and mathematics) which facilitate the sharing and accumulation of collective wisdom

3. A reasoning or synthesising faculty

4. The ability to build scientific instruments that extend our biologically-given sensory range of the external world

Principle 3 – The human mode of comprehension facilitates the creation of a scientific image of the world that extends our biologically-given sense of ‘reality’.

Mental processing

Kant set out what he believed were the preconditions necessary for experience to be possible. He listed these as the Categories of his transcendental aesthetic (space and time) and transcendental analytic, which was a modification of Aristotle‘s categories consisting of (quantity, quality, . . . mode).

The preconditions that must be met for there to be meaningful experience are the preconditions that are met by our innate mental faculties. These are mental processes that occur, mostly unconsciously, as part of our everyday unquestioning interaction with the world. Here I list just four interrelated ones: segregation, focus, classification (grouping), and ranking . . . there are probably many more . . .

Segregation

When you look at a television screen you see thousands of pixels of different colours and shades. How does our brain segregate these pixels into meaningful objects so that, without conscious effort, we discriminate, for example, people, cars, tables and chairs – just as we do in real life?

Perceptual

Our perception segregates this visual field into discrete and meaningful objects of our visual experience – like people, trees, and cars, as percepts. This fragmentation of the world into physical objects in space all happens intuitively. We do not have to concentrate on ‘creating’ the percepts, they just happpen. This raises questions concerning the discreteness of the objects we discern in the ‘real’ world. But this is just one aspect of our mental processing.

Cognitive

The mind operates on a host of mental representations, not just images. Just as our minds detect discrete objects in space, so they also experience discrete objects in time that we refer to using the language of events, and cause and effect. There is an integration of visual images with the mental concepts of our cognition that turn the world into an orderly experience.

In this way the world is, for us, differentiated into discrete spatial and temporal objects. Without these objects we could not operate mentally – we would exist in a world that was ‘one great blooming, buzzing confusion‘ (philosopher William James).

This mental structuring of the world into meaningful experience (of which perception is a part), we call cognition and the meaningful objects of cognition are, for simplicity, referred to as concepts.

The point is that, as Kant pointed out, our minds structure our experience into a unity of meaningful objects or categories, this separation into objects of thought we can refer to as cognitive segregation.

Principle 4 – Segregation structures our world into meaningful representational units of experience, both those of cognition (concepts), and those of perception (percepts).

Needless to say we are still investigating the relationship between our manifest and scientific representations of cognitive segregation.

Cognitive focus

Though we have access to a vast number of mental categories we only focus on a few of these at a time. When watching television our visual field of colours and shades comes to us from a flat two-dimensional screen from which we segregate meaningful objects like people, cars, and trees. While watching the television we are only vaguely aware of other objects in the room because they are not the focus of our attention – even though we can quickly move our gaze to take them into account. Thought processes are the same. When I am thinking about the current political situation I am oblivious of the fact that polar bears hibernate in winter, because polar bears are not my focus of attention. This does not seem surprising: we simply cannot think of everything all at once and so we break up our ‘reality’ into bight-size pieces.

So, at any given time our cognition and perception not only segregate the world into meaningful units they also present, as it were, a foreground and background, they are directed towards a limited range of cognitive and perceptual categories and they automatically cut out unwanted influences as background or ‘noise’. This is sometimes referred to as ‘intentionality’ as the various ways that our minds are directed at, or ‘about’, objects and states of affairs in the world.

The constant and rapid discrimination of objects and shifting of our focus of cognition and perception is incredibly complex but again, it occurs intuitively and, unless we deliberately think about it, we are generally unaware that it is happening.[12]

Principle 5 – Focus restricts our active attention to background and foreground percepts and concepts.

Classification

When I go to a grocer to decide on a piece of fruit to buy for lunch I might, as it were, have placed before my mind’s eye a possible selection of different fruits. As the number of possible fruits increases, so too does the need to arrange them into mentally manageable groups. Our minds seem to do this kind of grouping or classifying on the run as part of the constant process of making choices. The kind of groups we form will depend on the goal or purpose we are trying to achieve. Going to the grocer I am probably thinking of flavour as the key grouping criterion. Perhaps if I was in a geography class I would be thinking of the fruits in terms of their country of origin, and if I was doing plant science I might be thinking of their botanical family. The point is that we are constantly making choices in life and in order to do so we must first assemble in our minds the groups of objects from which the choice must be made. The criterion for the grouping will depend on the purpose of the choice.

Our minds prepare us for action in the world by drawing on our evolved tool-box of innate categories (see Immanuel Kant) and the processing of the many cognitive categories that we have learned as individuals, many of these being passed on to us as the accumulated knowledge of the community in which we live. It is as though our minds are a library of categories, as units of understanding, that we can source to help us live in the world. We can, if we so desire, extend the library with new categories or improve the library by making the existing categories more efficient for the particular purposes they serve. To act at all we must rank or prioritise our categories, and the way we rank them will depend on what we are trying to do – our objective or purpose. Prioritisation allows us to make the inferences and predictions that we use to guide our behaviour. Without this capacity we could not operate in the world.

Principle 6 – Classification arranges objects into groups using grouping criteria that depend on the purpose for which the classification was devised.

Rank value

There are two aspects to classification. On the one hand it arranges objects into convenient groups, for example, a bag of fruit may be divided into apples, oranges, and pears without any value attached to the grouping. But on many occasions there is also a prioritization or ranking of the groups. This occurs as part of the process of making both conscious and unconscious choices.

The combined processes of grouping (classifying) and ranking (valuing, prioritizing, or selecting) are a pervasive aspect of our mental life and an inherent part of our cognitive focus. This mental process may vary from being more or less intuitive (consider the change in ranking of our physical needs (Maslow’s hierarchy) in the course of a day) to being a conscious deliberation, as when we decide on the particular clothes we want to wear each day.

Principle 7 – formation of groups may be based indifferently on similarities and differences, but more often, groups are given rank (value, prioritization, selection) based on our needs, desires, purposes, and reasons.

We might think of this ranking and classification as a higher-order operation of our innate Kantian reasoning powers – the act of classifying being a process of logic using just a few simple operators – ‘if’, ‘then’, ‘either’, ‘and’, ‘or’, and ‘not’ – to find the most efficient path to particular ends.

We can learn about the principles and methods of classification from taxonomists and librarians whose work it is to prioritize some categories of information in relation to others based on specific criteria. For any particular method of classification we need to know its goals, structural properties, strengths, and weaknesses[3] and the major ways of classifying things, whether physical objects like plants, or psychological objects like concepts, are relatively few.

How does this everyday and every moment way of grouping and selecting compare with the the scientific classification and ranking we use to organize plants and animals?

Scientific classification

Scientific classifications attempts to ‘map’ the external world as accurately as possible by minimizing the human-centred aspects of our minds (e.g. reference to the subject, particular times, and particular places).This facilitates inferences about likely outcomes in the external world and increases predictive value. Science is constantly refining its cognitive categories which are of many kinds … names of various sorts, theories, definitions, laws, principles, properties, pictorial representations, and so on.

As an example, botanists make a sharp distinction between artificial plant classifications such as those based on flower colour or edibility (a subjective classification based on a human preferences), and more objective natural classifications based on the structure of DNA and hence their biological relationship in the external world which reflects their evolutionary history.

Principle 8 – scientific categories are being constantly refined as new evidence emerges that appears to represent the external world more accurately and objectively.

It is now possible to see how both the intuitive and deliberative ways in which we group and rank objects in the world can link in with language to give us a picture of reality.

To be edited below –

The biology of science

Current scientific research is currently focused on what has been called the last major scientific frontier – the human mind and consciousness – essentially neuroscience, cognition, and the evolutionary and moral aspects of the mind and behaviour; areas of research now receiving substantial grants. Wikipedia lists more than 50 sciences to do with the mind and consciousness.

Already findings from research into cognition over the last few decades has informed the way we both understand and do science. Looking at science through the lens of biology has given us a new perspective on things.

Let me explain.

We must assume that just as evolution has, as it were, structured our bodies over time so it must also have structured our minds in a way that has enhanced our survival. The perceptions on which much of our science is based are a consequence of evolutionary selection. We know little about the perceptual world of dogs, cows, snails, or bees but it is safe to assume that their perceived ‘reality’ is very different from ours. Can we assume that our reality is the ‘real reality’ or is it just another animal’s way of perceiving the world? If our perceptions are simply yet another way of perceiving reality then does it make sense to speak of a ‘real reality’?

Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker notes that modern science has arisen from the intuitions and limitations of our stone age minds, forcing us to turn off some of the intuitions out of which it grew. In thinking about the relationship between science and language in ‘The Stuff of Thought’ (2008) Pinker shows how we embed the key scientific concepts of space, time, matter, and causality in everyday language. Nouns express matter as stuff and things extended along one or more dimensions. Verbs express causality as agents acting on something. Verb tenses express time as activities and events along a single dimension. And prepositions express space as places and objects in spatial relationships (on, under, to, from etc.). This language of intuitive physics may not agree with the findings of modern physics but, like all metaphor, it helps us to reason, quantify experience, and create a causal framework for events in a way that allows us to assign responsibility. Language is a toolbox that conveniently and immediately transfers life’s most obscure, abstract, and profound mysteries into a world that is factual, knowable, and willable.

Science, our senses, and reality

‘All the fundamental aspects of the real world of our experience are adaptive interpretations of the really real world of physics’ George Miller

Though we might be puzzled by George Miller’s notion of the ‘really real’ world, his sentiments are worth scrutinising in more detail especially as it is being claimed here that physics is not ‘really real’ but an extremely useful explanatory ‘aspect’.

Each of us experiences a physical world that is external to ourselves – a world that persists after we die and which therefore exists independently of our own personal experience, a world that is not fictitious, a dream, or a figment of our imagination. The whole of science proceeds on this assumption (indeed, we might call it the central dogma of the scientific grand narrative) and it is this grand narrative that sets science apart from many other intellectual ways of framing our world. However, we cannot experience this external world (our environment) directly but only through the filter of our senses and the processing power of our brains (as our percepts and cognitions). Our common sense tells us that we perceive the world ‘as it actually is‘[9] and that this is what we generally call ‘reality’, but upon reflection it is clear that we cannot know the world ‘as it actually is‘ we can only know it through the limitations of our senses. Each organism has adapted to its environnment by means of its own unique sensory apparatus and will therefore sense the world with its own particular ‘reality’. The reality of a dog will be different from that of a cow, bee, worm or human. Two thirds of the brain of a white shark is devoted to smell.

In our daily lives we assume the world around us is the one reality (naive realism). However we can understand how dogs, chimps, bees and snails can exist successfully in a world that would be perceived in a very differeny way than ours because they will have very different sensory information on which to base that reality – the external world will be represented diferently. This suggests that reality is highly subjective being different for different sentient creatures, but it does not mean that the external world is not real, just that it can be perceived in different ways. There is, as it were, a ‘real reality’ that is just perceived in different ways.

Evolutionary constraints on the senses

Our survival as a species has depended on how well, in the course of evolution, we have adapted to our environment and this in turn has depended on the effectiveness of our particular senses and brain. Our senses evolved, like the rest of our body, to cope with the historical circumstances of our ancestors and we now know that our senses are extremely limited in what they can tell us about the world compared with what it is possible to know. So, for example, our visual field is limited (bats can see or sense things that we cannot see) and we have a limited hearing range (dogs can hear much higher sounds than we can hear). No doubt the way our brains structure the world and process information is similarly limited.

Extending our senses

Since we depend totally on the evidence of our senses and our survival has turned on maximising our ability to sense and respond effectively to our environment (the result of which is the brain which has allowed us to populate and dominate the planet) so we need to also maximise the effectiveness of our environment-sensing apparatus. Modern science has become progressively occupied with improving our understanding of our environment by artificially extending the range of our senses using ever more sophisticated technology. Knowing that our visual range is limited we have extended it by constructing glasses, telescopes and microscopes. Knowing that our auditory range is limited we have built machines that can detect sound that the human ear cannot detect. Through the steady improvement of technology we can now experience our planet and universe on a grand scale through radio telescopes, radar etc., and on extremely small scales by using electron microscopes and particle accelerators. Since our brains cannot carry out complicated mathematical calculations we have built computers that can do these calculations for us. Above all mathematics allows us to explore possibilities and dimensions that the human mind cannot grasp in any other way. Viewed in this way humanity has, through technology, artificially extended its reality way beyond both its own natural limitations and also beyond that of all other creatures. This is no doubt a major reason why humans dominate the planet today.

Life and ‘self-correction’

Organisms are self-replicating systems that exist for brief periods of time. When they replicate the new organisms or ‘children’ are not necessarily exactly the same as their ‘parents’. Those ‘children’ that fit better into the environment tend to survive and reproduce. Through this purely mechanical, non-conscious process (natural selection) new characteristics arise in new generations of organisms that mean they fit better into their environment. Evolutionists say that the organisms have adapted to their environments as a consequence of natural selection and we call the change they undergo over many generations evolution. Remembering that this is not a conscious process we can nevertheless, for simplicity, refer to it metaphorically as ‘self-correction’ or just ‘trial and error’ (see Purpose). By means of this simple non-conscious mechanism science can account for the origin of all of today’s animals and plants right from the first ancient replicating molecule(s).

The point is that unconscious ‘self-correction’ is a part of the physical interplay between organism and environment by which any organism ‘fits in’ to its surroundings over the long term.

Behaviour & ‘self-correction’

Unlike plants, animals constantly move through their environment encountering diverse conditions. Not surprisingly as a consequence of motility their sensory apparatus became far more sophisticated than that of plants. To coordinate the mass of incoming sensory information animals have developed a nervous system with a ‘control-centre’ or central nervous system the most complex of these control systems we know being the human brain.

The complicated interaction between organism and environment that we call behaviour can be a very simple interaction of stimulus and response as when the unicellular amoeba moves away from a particular chemical, but it can also be an extremely complicated instinctual or innate behaviour pattern like a bird building a nest or a spider weaving a web. This behaviour is so complicated that we might perceive it as being conscious or considered because it anticipates the future. It seems that the spider builds a web for the purpose of catching a juicy fly. But the spider does not have conscious goals, its apparently purposive behaviour is a consequence of events that occurred in the past, because those of its ancestors that built webs were able to survive and reproduce. This kind of behaviour we refer to as being instinctive or innate. Even complex behaviour like this has also arisen as a result of a mechanistic process of ‘self-correction’ during evolution although we do see a kind of pseudo-purpose or proto-consciousness here (teleonomy).(see Purpose)

Innate or instinctive behaviour is hard-wired or inbuilt and carried from one generation to the next but many animals can also learn within their lifetimes developing a conditioned reflex or simply making a conscious note of circumstances. If a dog is treated badly it will avoid its tormentor. Is this ‘self-correction’ a result of past experiences, anticipation of what might happen in the future, or a combination of these? The boundary between innate and learned behaviour and the emergence of purpose-like consciousness is a difficult are that is discussed elsewhere.

The point is that we can understand how behaviour too can change, or evolve, by a process of ‘self-correction’ that may be either inherited or learned.

Categories of thought: cognitive taxonomy

How exactly does the brain make sense of, or structure, the torrent of information pouring into it from our senses? If we consider just our eyesight then it is clear that the brain somehow segregates individual objects from what must pass into the eye as a meaningless mixture of colours, textures, tones and so on. In other words the brain, through a historical evolutionary process of ‘self-correction’ now exhibits selective visual perception segregating our field of view into objects like buildings, trees, and people … extremely useful when we are driving. Also a highly adaptive trait that helps us pick out tigers! Aural perception is similar, unconsciously converting soundwaves into words and meaningful communication.

What is true for sight and sound is true for the general operation of our minds. Cognitive scientists now recognise that our brains are constantly classifying by detecting patterns and regularities that can be slotted into conceptual boxes. Our brains are highly skilled taxonomists. To make sense of the world brains pigeon-hole regularities into a host of categories that help us understand what is going on both inside and outside ourselves and the categories can take many forms including: pictorial representations, names, explanations, definitions, descriptions, principles, theories, and laws. This process of mental categorisation we can call cognitive taxonomy.

Science as cognitive taxonomy

We are constantly reorganising, adding to, and improving the categories that we use to understand the natural world,[11] both our individual experience and our collective cultural understanding. Our categories of thought enable us to not only structure the world but to also infer additional properties so the greater the match between our categories and the external world, the better we can understand and manage the external world and, in biological terms, the more likely we are to survive and reproduce. From this point of view science can therefore be characterised as the steady improvement of our cognitive taxonomy and we can understand how this steady refinement does not require the use of words like ‘truth’ but can be described as ‘progress‘ or ‘improvement’ as our categories make a better match between our inner and outer worlds. We have surely become much better at this over time since we have been able to manipulate the external world in ever more effective ways.

On this view the method of cognitive taxonomy as a mode of reasoning is no different from that used in any other field, except that it is cognitive taxonomy within the scientific domain.

Reason as conscious self-correction

See Reason & rationality

Aristotle described humans as rational animals. We can speculate that as brains on the human line of evolution increased in complexity, so ever more processing power became available. We can only assume that the self-awareness we call consciousness or sentience was a consequence of this neuronal complexity. In the long history of transition from inorganic to organic replicating matter, once the mechanism of self-correction began it had, in one branch of the evolutionary tree, resulted in matter that had become aware of its own existence, of its own history and origins and, through the development of technology even calculated the age of the universe itself and the causes for its own structure.

This sense of self-awareness marks the point where some sentient animals, humans, can construct complex imaginary futures as a way of planning possible future action, and exhibiting consciously purposive behaviour.

Though we cannot attribute conscious human-like aims and goals to replicating molecules, once organic matter set off on the path of self-correction we can understand how reason – as conscious decision-making based on action selected from multiple imaginary futures – is also a form of self-correction, as though natural selection itself had become conscious.

It is the capacity for self-correction (natural selection) that is at the core of the living world. Self-aware self-correction – reason – is the single key factor on which future human evolution depends.

But nothing is new. If cognitive taxonomy is indeed the way we make sense of the world and a useful way to view science – the mechanism of reason and scientific discovery – then this is not a new insight, it was known thousands of years ago. It also explains why many modern philosophers have considered their discipline as contiuous with science.

‘(the) analysis of the order and concatenation of existence as a reasonable and intelligi(ble) system … the connection of one idea with another, on the relation between one stage in the complex scheme of actual existence and another. To bring together and divide, to see differences where they are concealed, and to find sameness between things different, to discriminate and connect kinds and classes … (in a) discussion or conversation (dialectic) … (this) according to Plato is the true art of the philosopher’

William Wallace 1880[8]

Commentary & sustainability analysis

Our assumptions about ‘the way the world is’ inevitably affect the way we will manage that world.

This web site has argued that it is a scientific world view that provides the most compelling account of ‘the way things are’ because its principles, theories and explanations can be tested and improved.

However, the world as presented to us by science is a strange and counter-intuitive one indeed; it is a world that does not square with our common sense intuitions. It is as though we live in two worlds, the world as presented to us by science (the Scientific Image) and the world as presented to us by our common sense (the Manifest Image). At the end of the day science is just metaphysics – a system of beliefs – its strength is that it is metaphysics that works; it is strongly corroborated belief, and it is also an interpretation of the world that minimises the influence of our uniquely human perspective.

It is now possible to consolidate some general conclusions about our scientific world view based on the principles established in this article.

Mental activity includes at least four interconnected innate processes that may be either consciousl or unconscious: segregation, focus, classification or grouping, and ranking. Segregation structures our world into meaningful representational units of experience, both those of cognition (concepts), and those of perception (percepts). Our minds not only fragment our experience into meaningful categories, they also focus our attention on these mental elements into background and foreground percepts and concepts: that is, we do not experience all available concepts and percepts at once. Classification then arranges objects into groups according to grouping criteria that depend on the purpose for which the classification was devised. Formation of groups may be based indifferently on similarities and differences but, more often, groups are given rank (value, prioritization, selection) based on our needs, desires, purposes, and reasons, referred to here as rank value.

Key points

- Scientific facts can always be challenged: they are neither absolute truth nor the world as it actually is – they are strongly corroborated belief.

- Scientific categories (names, concepts, theories, principles, definitions etc.) are constantly refined as new evidence emerges that represents the world more efficiently

- Each sentient organism experiences the external world in its own way according to its uniquely evolved species-specific sense organs: it has its own particular mode of ‘comprehension’.

- Humans use the tools of ‘science’ (mostly reason and technology) to look beyond their biologically given senses to enhance their interpretation of the world, of ‘reality’.

- Science is now providing us with an improved understanding of how our minds create our common-sense, everyday, human, comprehension of the world.

- the mind segregates the world into cognitive categories as meaningful representational units, both those of perception (percepts) and those of cognition (concepts)

- though experience of the world is different for different sentient organisms, their sensory apparatus does not construct the world but interpret the same world in different ways: the external world is not an illusion

- Human percepts and concepts are not objects as they exist in the world outside our minds, they are mental representations of these objects structured by our uniquely evolved and species-specific sensory system. Though different species experience the world (reality) in different ways, these different experiences are nevertheless triggered by the same external world. Humans are privileged in having technologies that can extend their natural sensory range, their perceptual and cognitive capacity. Symbolic languages allow us to accumulate, share, and refine a body of stored knowledge as collective learning and science

- This article has identified four interrelated mental preconditions for our effective operation in the world – segregation, focus, classification, and valuation. These are innate faculties of the mind that use both consciously and unconsciously: referred to here as mental processing.

- Historically, these mental structuring processes have been an integral part of the intuitive way that we represent the world. Our evolutionary persistance indicates that this mode of representation is fit-for-purpose (our survival, reproduction, flourishing) :

1) Segregation – division of the world into mental categories as meaningful representational units, both those of perception (percepts) and those of cognition (concepts).

2) Focus – our minds simplify awareness of the multitude of these mental categories by restricting our awareness at any given time to a small proportion of those available. That is, mental categories are organized into a foreground and background

3) Classification – mental categories are not experienced passively, they are grouped (classify) according to similarities and differences that depend on the purpose of the classification

4) Valuation (ranking) – our lives depend not only on arranging mental categories into meaningful groups, but in also ranking these groups according to purpose. That is, we are constantly making choices and this entails not only mental taxonomy but ranked taxonomy (as valuation, prioritization, selection) based on our needs, desires, purposes, and reasons.

These mental capacities seem to operate simultaneously and with varying degrees of consciousness. The fact that all these processes can take place independently of any conscious effort, and that we all (as a species) engage them suggests that they are innate.

- About 50,000 words are listed in the standard English dictionary

- Hierarchical metaphor confuses and complicates the objects and relations investigated by science, creating misleading paths of logical inference

- Nested hierarchies can be understood in two ways as being either progressively inclusive or progressively divisive – to understand and describe the objects within the hierarchy we can proceed either by analysis or by synthesis (or both)

- The analytic process of explanation of the large and complex in terms of the small and simple persuades us that parts have some ontological privilege (are more real) than wholes

- The greater difference in size and complexity (causal relations and scale) of the cognitive units under consideration, the greater the difficulties in communication and translation

- Perceived physical units of matter have no intrinsic (ontological) precedence or priority over one-another

- The appeal of small objects over large ones lies in their apparent explanatory power (epistemology) not their material properties (ontology)

Media Gallery

Ontology, science, and the evolution of the manifest image

Alpha Omega – 2018 – 1:00:54

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

Hierarchical levels of organization:

. Scales or aspects of understanding

. Frames of explanatory reference

. Domains of knowledge

. Cognitive categories