Morality

Image generated by AI as a visual summary of the content of this article,

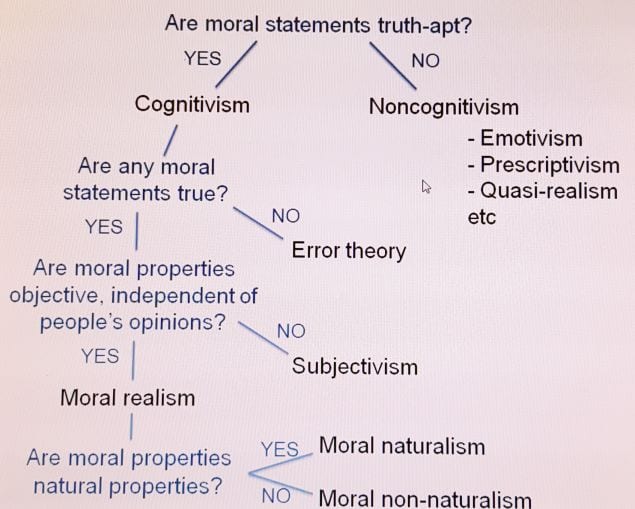

The moral landscape in a nutshell

Moral philosophers help us to think clearly about morality by providing a framework of categories for our ideas (useful once the terminology has been mastered).

First, a few ground rules: there is no philosophical distinction between ethics and morality; in philosophy statements that can be true or false are called propositions; ‘objective’ as used in this article means ‘mind-independent’. Moral philosophy can be divided into three main areas of study.

Applied ethics (practical ethics) addresses specific ethical problems (e.g. whether abortion is right or wrong)

Normative ethics explores the general rules and principles that guide our behaviour – it gives us frameworks and theories for dealing with the problems of applied ethics. There are three major theories – virtue ethics, deontological ethics, and consequentialism. These will be discussed shortly

Metaethics deals with the origin, scope and meaning of ethical language. What do ethical terms express – are they universal or relative? Can we speak of moral progress? Are moral statements truth-apt. Is the statement ‘Abortion is wrong’ a proposition? This distinction is a critical one in moral philosophy. Moral realists say ‘yes’, anti-realists say ‘no’

To develop your own metaethical ideas you will need to see where you stand in relation to an elaborate field of philosophical positions. Here is a quick overview.

NORMATIVE ETHICS

Theories used to decide what is right and wring, better or worse.

Secular empiricism

To persuade other intelligent people to adopt your particular code of conduct you will need to justify your moral actions in very clear terms. In such circumstances it soon becomes apparent that most of us think about morality in a muddled way, based on a number of indistinct common-sense-like principles that we use in an arbitrary and inconsistent manner. Morality seems to be a mixture of religious precepts, civil laws, and social conventions all tied up with our own particular views and values.

For the sake of ethical tidiness we can go to the moral philosopher for assistance: it is her job to assess and organize the various ethical theories, principles and practices that people have adopted throughout history and structure them in a way that helps us understand where our own particular moral views fit into the schema of ethical thought.

All societies have normative rules because they assist with the smooth running of their various institutions and, of course, the particular norms accepted may differ from one society to another.

For convenience we can divide our moral lives into three broad categories:[1]

1. The moral act itself – what it is that makes an act right or good: the investigation of ethical theories

2. The origins of moral judgments and moral intuitions – once a religious question, today this is now treated more as a scientific question involving subjects like neuroscience, evolutionary psychology and moral psychology

3. The overall purpose, function or goal of morality – a question traditionally addressed by philosophers

1. Moral acts and ethical theories

Much of the hard work of moral philosophy concerns the question of what constitutes a moral act – what is it that makes an action right or wrong, good or bad? In general terms this question has been answered by theories that concentrate on each of the three elements of the moral equation: the moral agent, the act itself, and the consequences of the act. An example of an ethical system based on the moral actor is Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics which focuses on the virtuous person, while an example of a moral theory based on the moral act would be Immanual Kant’s Deontology which focuses on the the rules that prompt the moral act (the categorical imperative – Act on a principle or maxim that you can will to be a universal law). Theories based on the consequences of moral acts are referred to as consequentialism, one form of which is utilitarianism.

Certainly in the Western tradition these three types of theories – Virtue Ethics, Deontology, and Consequentialism – constitute the major approaches to ethics so we need to look at them in more detail.

Virtue ethics

The foundations of Western ethics were laid down by the ancient Greek philosophers in the Axial Age who regarded morality as the search for the highest human good, known as eudaimonia (eu-true>, daimonia-spirit).[11] Eudaimonia was like an ultimate human goal,[4] it was the meaning and purpose of life … a self-evident human goal that did not require a law-giver or ultimate moral authority. The precise translation of the word eudaimonia is uncertain but it is roughly equivalent to what today we would call ‘happiness’, ‘well-being’, ‘human flourishing’, or ‘personal and social harmony’: it was what Aristotle regardedas the full actualisation of human potential. Though the general goal of eudaimonia was uncontroversial the means of achieving it was a matter for keen philosophical debate.

For Plato eudaimonia could be achieved by living ‘The Good Life’ (see Reason) which was a just life attained when the three components of the mind – reason, spirit and appetite (what today we might loosely call ‘head’, ‘heart’ and ‘gut’) – were in harmony, with reason in control. This harmony could only be achieved within a just society, which is what he outlined in his book The Republic (see Reason). Moral character (arête, virtue or excellence) was critical and different philosophers had their preferred virtues. Especially popular were the cardinal ‘inner’ virtues of wisdom, justice, temperance and courage, although ‘outer’ factors like relationships, social peace, physical beauty, and money were also included.

For Aristotle the path to eudaimonia consisted of virtue informed by reason (‘doing the right thing for the right reason‘) and he outlined his ideas in the monumental Nicomachean Ethics. He regarded virtue as the moderation of extremes with pleasure and happiness not ultimate goals but by-products of the virtuous life. Aristotle, like most of the other Greek philosophers, regarded reason as a key ingredient of eudaimonia. Humans were the only rational animals and virtue was ‘right behaviour habituated’ a precept still observed today as a key aspect of parenthood and education. The word ‘ethics’ derives from the Greek ethos – habit or custom. For Aristotle everything had a purpose or telos and for humans the good life would be fulfil that telos: we would express this in a general way as achieving our maximum potential given life’s various constraints. Guidance in virtuous behaviour could be given by virtuous individuals. Aristotle believed in strength of character. The philosopher Epicurus in contrast maintained that virtue was on the path to the greatest goal of eudaimonia which was happiness or pleasure (for Epicurus pleasure was not self-indulgence but freedom from pain, fear, and distress).

Plato thought that reason was part of the transcendental world of forms or ideas, while for Aristotle reason was the means by which humans could achieve their highest function or purpose, which he called telos): reason was a mechanism for achieving maximum human potential given the constraints of human nature. Reason, then, was needed for the development of good habits, something which we all have capacity for, but something which needs ‘training’. Reason was therefore the tool we use to regulate individual and socially destructive behaviour, to relieve suffering, resolve conflict, assign praise and blame as punishment and reward, and increase freedoms.

Aristotle’s virtue ethics, after a period in the doldrums, is now finding renewed support. However, virtues are slippery concepts that can vary with time and place. This makes it difficult to regard virtue ethics as a comprehensive normative theory since deciding what constitutes a virtue requires us to first know what we ought to do.

To decide what we ought to do ethicists turn to two pre-eminent ethical theories: deontology (which concentrates on intentions and the following of rules), and consequentialism (assessment of the consequences of our actions).

So, to (over)simplify and distil current thinking we can frame a key question about morality today in the following way: ‘Do we act morally in consideration of the consequences of our actions or because of inviolable rules? That is, are we consequentialists (utilitarians) or deontologists, or some combination of the two?’ In answering this question for ourselves we must bear in mind that these two theories are not necessarily mutually exclusive so, for example, many consequentialists accept the value of general guiding moral principles.

It must be said at the outset that the search for an overarching moral theory that is logically coherent and satisfying has proved elusive. Both these schools of thought confront their own difficulties and it is common for people to have ‘mixed’ views.

Deontology & the Golden Rule

David Hume had claimed that reason alone could not motivate action, ethical behaviour was a product of the will and that all we could hope for in our moral lives is ‘a stable and general perspective‘. Kant agreed with Hume that intuition, not reason, was the motivator for behaviour but if behaviour was to be moral then reason must be the agent that makes it so. Reason is the guide but not always in control like, as Plato had suggested, the charioteer trying to control his horses.

Deontologists (Greek deon-obligation, necessity) in the tradition of German philosopher Immanuel Kant maintain that certain actions, like lying, cheating, and being loyal are simply right or wrong.

Probably the most widely known moral precept is the Golden Rule – some version of ‘Do as you would be done by‘. This principle is a keystone of world religions it has also been endorsed in various forms by many great thinkers. There is Spinoza’s Viewpoint of Eternity, Kant’s Categorical Imperative, Hobbes and Rousseau’s Social Contract, Locke and Jefferson’s self-evident truth (that all men are created equal), Adam Smith’s ‘impartial spectator’, modern philosopher John Rawls’s ‘veil of ignorance‘ (suggesting social contracts be tested by asking people to agree to them when they have no idea of the consequences of the contract for themselves), and moral philosopher Henry Sidgwick’s ‘The Point of View of the Universe’.

The Golden Rule appeals to reason, inviting us to look beyond our own self-interest by pointing out that it is not fair to privilege oneself over others: it is the rational advocacy of a rule that is easily understood and true for everyone. Certainly a valuable guiding principle in life, like most rules it has a flaw. People are different: you might not want the same things that I want, so universalizing my morality will not always work. Even so, this is morality based on reason, telling us that it is logically inconsistent to apply a moral principle only to yourself.[1]

For many people the dogmatism of deontology is unacceptable since we can think of many exceptions to its rules. And yet we do tend to follow general rules of behaviour in a deontological way albeit in an undisciplined manner.

Consequentialism

The most popular strand of consequentialism today is utilitarian consequentialism (the maxim for moral action should be the greatest happiness for the greatest number) made famous through the writing of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill and suggesting that although moral acts are carried out for many proximate (immediate) reasons the ultimate guiding principle is the maximisation of pleasure (Hedonistic utilitarianism) or happiness (which entails the minimisation of pain and suffering). Bentham’s contention that pleasure and pain underlie our moral behaviour was pre-dated by over 2000 years in the philosophical ideas of Epicurus of Samos, Epicureanism and utilitarianism being in essential character the same. However, consequentialism, especially utilitarianism is enjoying a period of popularity, probably because it avoids the dogmatism of deontology whose rules seem to have many exceptions. Utilitarianism, sometimes characterised as a means of maximising welfare through a kind of societal cost-benefit analysis, was given its most rigourous expression through the work of Cambridge philosopher Henry Sidgwick.

Criticisms of utilitarianism take various forms: is its goal average or total happiness for the greatest number; we can think of acts that seem ‘right’ but which do not support the maxim and others that seem ‘wrong’ but which do support the maxim; we feel ambivalent about committing extreme acts that are generally regarded as wrong in deference to greater happiness; there is a lack of clarity concerning the definition of happiness itself; does utilitarianism apply to just humans or all sentient beings? Utilitarianism may clash with our moral intuitions and it can be extremely demanding if rigidly adhered to. Just as deontology seems to present us with exceptions so the kind of ‘moral calculus’ that consequentialism entails, weighing up the ‘fors’ and ‘againsts’ in any situation as units of pleasure (‘hedons’) is problematic and can present us with either impossible choices or impossible decision-making complexity. For example, if donating your organs right now could save five lives should you make this sacrifice? Doesn’t the maximisation of benefit demand that you should? Utilitarians promote the universal moral precept of the greatest net benefit in relation to ‘ends’ (perhaps tell a lie under circumstances that leads to overall benefit), while deontologists use universal principles based on means (never lie).

Utilitarianism comes in several flavours. Act utilitarianism concerns itself with the morality of individual or ‘token’ acts while rule utilitarianism concerns itself in a more general way with similar kinds of moral action. Preference utilitarianism defers to the common good and our tendency to privilege our own interests, maintaining that ‘On balance we should do what furthers the interests of those affected’.[3] This fulfills the criterion of universalizability (the Golden Rule of ‘do as you would be done by‘) which has proved so popular among philosophers and religious traditions throughout history.

Utilitarianism for all its difficulties is a practical moral theory that is relatively free of academic jargon and complication: it is a moral theory that, for better or worse, has captured the spirit of our times.

Where do our moral decisions come from?

Outside & inside – the organism-environment continuum

On the one hand we might regard morality as being imposed on us from ‘outside’ ourselves by our parents, civil law, or divine law. Religion aside, it would seem that ultimately morality must come to us from ‘inside’ as either a feeling of what is right and wrong resulting from our free will, the result of accumulated personal experience, or what we might call a moral intuition, or maybe the result of considered deliberation as the use of our reason. The question of internal and/or external sources and determinants is reminiscent of the nature vs nurture debate and we will return to this later. However, if morality is generated, at least in part, from within us then ethical questions become less to do with philosophy and more to do with biology, more specifically moral psychology (the nature of moral intuition) and the behavioural sciences. The ‘inner/outer’ dichotomy also brings to mind the question of subjectivity and objectivity. Perhaps we think of our behaviour as the result of rational consideration with reason playing a key role: after all we often intuitively regard ‘wrong’ behaviour as irrational. Cambridge University moral philosopher Henry Sidgwick regarded ethics as ‘any rational procedure for determining what we ought to do‘.[5][7] Indeed there are grounds for suggesting that morality be defined as the subjugation of our natural inclinations and impulses to reason. On this point philosophers and scientists are undecided. Whether rationality is the primary source of our moral decision-making remains one of the most challenging current questions in ethics and cognitive science.

Biologically it would appear that whatever goes on in our minds when making moral decisions that mental activity is generated as a consequence of interaction with the environment: it is part of the adaptive interaction between organism and environment.

Biology & evolution

Biological organisms are ‘primed’ by evolution (their genetic makeup) to survive and reproduce. This is regarded by biologists as their meaning and purpose. As humans we desire to not only survive and reproduce but to flourish, that is to be ‘happy’, which may also be regarded as part of our meaning and purpose.

Modern research takes the question of origins back a further step. If indeed reason and emotion are mainsprings of our ethical decisions then how do we account for these traits in scientific and evolutionary terms. Can evolution inform our attitudes to morality? Clearly emotions play a major role in our behaviour as various desires and emotions pull us in different directions. To what extent is our behaviour selfish or egoistic and to what extent altruistic? How do all these factors fit in with the external world which includes other people? Sometimes not very well. So what is the factor that corrects or controls these inner forces, that allows us to self-correct and therefore continue to survive, reproduce and flourish? Non-adaptive moral behaviour will be weeded out by natural selection but self-correcting reason provides us with a short-cut. Moral psychologists have isolated a commonality of moral intuition across cultures suggesting an innate source of our moral behaviour whether it be the ‘five foundational domains’ or reason and variations of the Golden Rule (see later). The five foundational domains are regarded by moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt as the mainspring of moral behaviour in all humans. They are the innate factors motivating us in our moral decision-making and considered in more detail in the article on moral psychology but they flesh out what we mean when refering to ‘moral intuitions’ and can be listed briefly here as: care/harm, fairness/cheating (reciprocity, altruism, empathy, cooperation, free-riding), loyalty/betrayal, sanctity/degradation, authority/subversion (hierarchy, respect, dignity, honour).

Reason & intuition

Though the ancient Greek philosophers placed emphasis on the use of reason in daily life, they were fully aware that carrying out this precept was no simple matter. Is it reason that drives our moral behaviour or our moral intuitions (our natural inclinations like the emotions of various kinds that guide our behaviour)? Is an objective reason always accompanied by a desire or are desires something that is ‘added’. Are rationally binding rules like the Categorical Imperative independent of the will as Immanuel Kant claimed? The question of the extent to which our moral decision-making re is still the unresolved question as to whether our moral decisions do or should come from our reason or our will/passions as suggested by Hume. This is an important unresolved issue of cognitive science and it is discussed in the article Reason & morality.

Subjectivism and objectivism

Certainly normative laws seem different from scientific laws and evidence-based (empirical) statements of fact. Scientific laws seem to be stronger in some way. This intuition about the difference between scientific and normative laws is cleverly illustrated by the T-shirt inscribed ‘gravity is not just a good idea’.

Does this suggest that morality is ‘just a good idea‘ – a personal opinion or matter of taste? Is there really an unbridgable divide between science and ethics? When we have moral disagreements are we destined to simply agree to differ with no means of finding a ‘rational’ solution?

One way of thinking about these matters is to ask if, and under what conditions, we can say that ethical statements are true or false. Can there be moral facts (circumstances that make a moral belief true) an if so, what is the relation between these facts and the facts of science, empiricism and induction?

Objective ethics

Objective ethics claims that there is objective truth or falsity in moral judgments and that this truth or falsity is independent of ourselves or our culture – it does not depend upon the beliefs or feelings of any particular person or group of people. An axiom-like basis for morality like ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ or ‘the maximisation of human flourishing, happiness or pleasure’ seems sufficiently objective (publicly acceptable, not based on individual preference) for us to claim that moral judgments can be described as true or false. This supports our tendency to use reason to defend moral actions and provide resolution by giving the best reasons for an action when considering its effects on all concerned.

Trying to be ethically objective like this counters our tendency to privilege our personal interests. It also supports our seemingly universal moral resistance to actions like unprovoked violence, which is rarely considered a matter of subjective taste, as well as our intuitive acceptance of ‘self-evident truths’ as enunciated in the constitutions of many countries.[2] Reason in such cases seems to point not so much to absolute truth but to the most justified or most evidence-based course of action (but more of this later).

Subjective ethics (relativism)

Subjective ethics, by contrast, can takes various forms. Emotivism, sometimes called the ‘boo-hooray theory’, claims that morality is just an expression of our emotions. Expressivism claims that moral statements are not about facts but about attitudes. In such cases it becomes extremely difficult to claim that moral progress is possible.

The truth and falsity of judgments made by the different schools of thought is sometimes expressed in terms of cognitivists and non-cognitivists.

Non-cognitivists claim that moral judgments do not state anything that we can know, that is, they cannot make statements that can be judged as true or false, they simply express feelings or attitudes, prescribe certain actions, or attempt to sway others to a particular point of view. In contrast cognitivists claim that moral statements present the truth about our obligations and our reasons for action. However, a cognitivist subjectivist may claim that moral statements can be true or false while not applying to everyone (they may, for example, depend on the attitude of the speaker or a particular culture) while a cognitivist objectivist claims universal truth or falsity of moral statements.[6]

Subjectivism was popular for much of the 20th century and is still supported by some philosophers although the idea that ethics has a rational basis is gathering popularity. If you find subjectivism unconvincing then it can be expressed in a more moderate way by claiming that morality is culturally embedded: it is not necessarily a matter of individual taste but more a result of cultural tradition.

Cultural relativism

The issue of subjective and objective ethics becomes less academic and more a matter of practical ethics when we consider culturally conflicting moralities, whether based in religion, cultural tradition or custom. Subjectivism tends to adopt a position of tolerance as cultural relativists are cognitivist subjectivists: the truth of a moral statement being relative to its cultural context. This is expressed through sayings like ‘live and let live’ and ‘when in Rome do as the Romans do’. So, for example, expressing disapproval over ethical differences between cultures would not be considered appropriate behaviour. But there are some difficulties with this approach.

Cultural relativism is resistant to moral change as it is usually based on numbers (majority opinion) in any particular circumstance. It also presents the quandary of supporting, say, slavery, racial oppression, genital mutilation, and extreme cruelty as acceptable social conventions, simply different and equally valid modes of behaviour that some may accept and others reject.

For the objectivist extreme cases like those listed above are ‘objectively’ undesirable demonstrating that morality is not relative and that we are entitled to make evaluative claims about different moral systems. How we express this moral disapproval is clearly a moral dilemma in itself.

Moral progress

How and why does morality change?

If morality is subjective then not only is there little incentive to change current practices, but the whole idea of moral progress becomes meaningless because no form of behaviour can be regarded as an advance or improvement on any other.

We certainly feel intuitively that moral circumstances can be improved. Steven Pinker in an examination of human violence throughout history, The Better Angels of Our Nature: the Decline of Violence in History and its Causes (2011) presents compelling evidence for steady, if briefly fluctuating, decrease of human violence over time. Faced with on the endless stream of negative and violent news this might seem counterintuitive (this is a framing issue (see Reason). However, only a few hundred years ago in Europe the public disembowelling of some unfortunate was treated as family entertainment.

Evidence for moral progress includes the world-wide abolition of slavery, a decrease in racial prejudice, the decriminalisation of homosexuality, improved treatment of women, and a reduction in both capital and corporal punishment. The rate of moral progress is probably increasing. Since 1950 we can list the advent of feminism, the human rights movement, animal liberation, removal of smoking from public places, and the launch of gay rights. Children today on average live in a much more peaceable family and school environments in spite of the occasional pathological shootings.

Moral judgment

‘Police are such judgmental people’ Woody Allen

We have also become less judgmental and more cautious in the way we express our morality – more politically correct. Many behaviors have changed from being perceived as moral failings to becoming lifestyle choices. They include divorce, illegitimacy, being a working mother, marijuana use, and homosexuality. One-time moral laxity is now treated as misfortune as ‘tramps’ or ‘bums’ become the ‘homeless’. Syphilis, once widely known under a range of pejorative terms is now a ‘sexually transmitted disease’.

Accounting for moral progress: the mechanism of change

How do we account for moral progress, what have we done to achieve this outcome? Massive change over such a short time period indicates that this cannot be a genetic change in human nature. How did the once universal capital punishment become virtually eliminated in the face of the logic of ‘an eye for an eye’?

Steven Pinker suggests that moral transitions occur by means of a ‘norm cascade’. When a controversy arises intellectual elites (the educated and articulate) defy the majority based on rational arguments. This tends to be pushed through a process of formalisation. The change is then observed to have little if any negative effects and becomes accepted as a norm such that reversing the decision becomes not only unlikely but absurd. Radical opponents then serve to cement the newly established norms. Pinker also suggests an Escalator of Reason : that, over time, there has been an ‘intensifying application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs‘ which ‘can force people to recognize the futility of cycles of violence, to ramp down the privileging of their own interests over others’s, and to reframe violence as a problem to be solved rather than a contest to be won. In other words it is reason that is at the vanguard of humanitarian reform.’[6] Slowly, over the course of history, we have seen the ascendancy of reason over impulse, while recognising that it is within our nature to revert at any time.

Pinker suggests that cosmopolitanism encourages thinking in more abstract universal terms which counters the tendency to adopt local parochial and inflexible thoughts and attitudes. Support for this idea comes from the ‘Flynn effect’ whereby teenager IQs have actually increased since the test was devised as a result, according to researcher Flynn, of a more critical scientific mode of thought transmitted through our culture.

3. What is the purpose of morality?

Can there be a single purpose for all ethics, an ultimate goal – a goal that is an end in itself which does not depend on some further goals, a goal that is universal and therefore objective?

Perhaps there are multiple candidates for this role. Henry Sidgwick suggested ‘justice’, ‘benevolence’ and ‘prudence’ as self-evident or rationally intuitive ‘axioms’ on which ethics could be based. Many philosophers have suggested that a prime candidate for this ultimate principle is ‘happiness’ However, making justice and honesty absolute principles is difficult because we might find exceptions involving consequences that we cannot accept (e.g. the ‘white lie’).

The ideas of many philosophers seem to have coalesced around the old Epicurean notion of ‘everyones’ happiness‘ (as pleasure and freedom from pain) as a single categorical (universal) duty – this being the moral position called ‘utilitarianism’.

Rational egoism

What could be more natural than rational self-interest? Shouldn’t this be taken as a fundamental, even obligatory, axiom of morality?

In general, making other people happy makes us happy ourselves … but not always. What ought we to do in these difficult cases when there is a clash between our own happiness (egoistic hedonism) and the happiness of all (universalist hedonism)?

While this is certainly a reasonable position the universalisation of rules constantly moderates our natural self-centeredness by abstracting to the realization that the good of any one individual is of no more importance than the good of another. A utilitarian would claim that although we have strong and motivating self-interest, when one act impartially creates the greater happiness then this is what we ought to try to do.

Morality & sustainability

In the course of the last 50 years there has been an increasing awareness of human influence on the biosphere, climate change being just one of many global environmental concerns. If humans are to flourish then the environment must be protected – and that includes mountains, forests and rivers as well as sentient animals. If we accept that our moral goals must be congruent with our broader goals then social, environmental and economic behaviour must all be included within the general moral sphere. The foundations of this idea and its relation to modern biology are explored more in the article on Meaning and purpose. The relation between ethics, economics, society and the environment are discussed more in the article on environmental ethics.

Modern biology is unambiguous in treating the ultimate goal of living organisms as survival and reproduction (its ‘purpose’) – it is what they do, passing on DNA to the next generation, it is something that is built into the system. As if in agreement with this idea Aristotle tells us that the highest good for humanity is to fulfil that which is in its very nature, its telos, and that is the desire to flourish and be happy (eudaimonia or well-being). Biology and the ancient Greek philosophers appear to be in agreement here. Modern utilitarians endorse the idea of common happiness.

Since the time of Plato and Aristotle the known Western world has extended physically from the Mediterranean and surrounds across the planet and out into the universe, and intellectually into space and time. In spite of the wonders of Greek mathematics it was only in the 17th century with Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world that we became aware that our plaet was finite. In the last 100 years it has become increasingly clear that human flourishing is becoming increasingly precarious through its influence on the natural world.

Our bodies, including our minds, only exist in relation to an outside world, the environment. Happiness is a mental state that only exists as a result of what is going on in the outer world, the environment. If humanity is to survive and flourish, to be ‘happy’, then we must manage to the best of our ability those factors on which we depend. Expressed in practical terms that is our environment, our social relations and our economics. It is this that will permit us to flourish. What the ancient Greeks referred to as eudaimonia, the utilitariansd refer to as happiness and flourishing, we accept through the international program for sustainability which embraces the planet and community of life.

We have always realised that, as humans, we carry within us the capacity for irrational, inhumane, and self-destructive behaviour. As beings in the world we are not perfect: there is a flaw in our make-up. Christianity refers to this as original sin. Aristotle and the ancient Greeks understood that, all too easily, we can be swayed by our appetites and desires in a way that we might later regret and that, for our own good, this must be overcome by moderation and reason … the habituation of virtue.

In the last few decades science has given us the understanding and words that allow us to express all this in a new way. Evolution did not prepare us well for life in the 21st century: it prepared us for life in times long before the reasoned cogitations of Aristotle and the rise of of world religions. Our flawed nature comes to us from the distant past. To manage this inherited human nature effectively we must understand it as best we can. Morality has always been one way of examining its power and curbing its excesses.

METAETHICS

Moral realism (cognitivism)

Moral statements are propositions, they are statements about objective facts in the world and, as such, they are descriptive and can be true or false.

Are moral statements truth-apt?

No

Those that say ‘no’, that all moral statements are false, support Error Theory (J.L. Mackie) which claims that rightness and wrongness are not objective features of the world, they simply don’t exist – they just take on the character of descriptive statements.

Yes

Those that say ‘yes’ must ask if moral properties are objective properties of the world.

Those that say ‘no’ are claiming subjectivism (relativism). Individual subjectivism means e.g. ‘I disapprove of abortion’ so the truth of moral statements is relative to the individual, while cultural subjectivism (cultural relativism) they refer to the culture as a whole (it is important here to distinguish between descriptive relativism and metaethical relativism: it is a fact that different cultures have different moral systems but this does not mean that nobody is objectively right or wrong).

Those that say ‘yes’ are moral realists, they claim that some moral statements are objectively true e.g. abortion has the mind-independent property of wrongness, it is a descriptive feature of the world. There is then the question of whether moral properties are ‘natural’ (empirical or scientific) such that moral goodness is, for example, pleasure as an intrinsic good. Moral naturalism (e.g. Sam Harris The Moral Landscape) therefore regards moral properties as natural properties. Such a view has appeal because by this understanding morality can become a science, that goodness is, for example, wellbeing or flourishing as measurable properties of the world. Moral non-naturalism claims that though there are moral properties they are non-natural properties. Biologists especially might be attracted by the idea that enquiry into the natural world can increases moral knowledge in step with scientific knowledge. But can ethics be confirmed by science? Can moral facts be facts of nature? This question will also be examined.

Moral anti-realism (non-cognitivism)

Moral statements are not truth apt: they are statements about value, they are not descriptive, and not objective. (non-cognitivism, subjectivism) claims that value, right and wrong, are matters of personal choice giving morality flexibility such that moral propositions are not truth-appropriate, matters of value.

Anti-realism takes three main forms: emotivism (moral propositions are expressions of emotion, the ‘boo-hoorah’ theory associated with Ayer & Stevenson); prescriptivism (moral propositions are not descriptions but moral imperatives: they are prescriptions or recommendations) and quasi realism (moral factionalism associated with Simon Blackburn) that, for practical convenience we behave as though moral statements are true or false even though, in fact, moral properties are not real.

It is important to distinguish between emotivism and individual subjectivism. Individual subjectivism reports a moral view describing something that can be true or false, while emotivism does not report anything other than an emotional reaction.

Schematic representation of metaethical theories

Courtesy of a series of Youtube videos on the topic at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OBE50_tfAIA

Meta-ethics is the study of the discipline of ethics itself, including its scope and the nature of ethical properties, statements, and attitudes – addressing the broader question ‘Why should I do what I do – what is my justification?‘. There is then a major philosophical distinction between realists and anti-realists.

Moral realism (cognitivism, objectivism) claims that value, right and wrong, actually exist in the world so moral propositions can be true or false since they reflect matters of fact. Moral realism is of two kinds: ethical naturalism (naturalistic ethics) which claims that we have empirical knowledge of moral properties and that these are reducible to non-moral terms and properties – like needs, wants, or pleasures (rather than, say, the will of God), and ethical non-naturalism – which claims that ethical sentences are propositions, some empirically true, but not reducible to non-moral features.

Anti-realism

Religion – Divine Command Theory

For most of human history morality has been regarded as simply a set of rules or code of behaviour issuing from god(s) as divine decree. Since the advent of writing this divine code has been communicated through holy scripture. Perhaps the best-known examples in the West would be the Old Testament Ten Commandments of the Christian and Jewish faiths issued by God to Moses who wrote them down on stone tablets (hence ‘written in stone’) before presenting them to his people. Islam has Five Pillars while other religions have similar codes originating from a divine or inspired leader.

Ethical systems have traditionally been deeply embedded in religious belief and still are, as the majority of people on the planet are religious believers. There is a straightforward simplicity about this non-negotiable absolute set of rules as it clearly serves two major social functions. Firstly it reduces the possibility of challenge to human frailty and fallibility and, secondly, it provides the behavioural rules and aspirations that are necessary to hold societies together. Religious conviction has led many to question the basis of any morality that is not the consequence of divine decree: if God does not exist then why should we behave in a moral way? The simple answer to this problem is that we behave morally because life is better that way. Indeed, we can ask in reply: do we really only behave in a moral way for fear of what God, or society, might do to us?

God’s law, or will, is problematic in several ways. Apart from all faith being entailing belief without sound reason there is the difficulty of imagining how anyone could do anything that was contrary to the will of an omnipotent god and if God’s will prevails everywhere in the universe then God becomes an unnecessary component of moral discourse. Of course it may be claimed that God has given humans free will as an ultimately greater good. But if this is so then the atrocities, pain and suffering of the world seem hard to justify on these grounds. In addition, discovering God’s will entails the dubious business of interpreting the sacred texts. Plato pointed out that when God issued a divine decree like ‘Do not kill’ we are entitled to ask if he did this for a reason. If he did not have a reason then he might equally have said ‘Killing is good’. If you find the statement that ‘Killing is good’ distasteful or you believe that god would not have said this then, either way, your attention will focus on the reason without concern for the intermediary of God.

Regardless of arguments like these that put God to one side, theists tend to claim that just as we must use our reason to discover the wonder of Gods creation (natural theology) so we must also use reason to discover God’s will (morality). We might call this approach a kind of secular empiricism: it does not necessarily deny God but uses reason and evidence as its investigatory tool for drilling into morality.

Key points

- Our behaviour is governed by moral rules and values (norms) that impact the way we manage environmental, social and economic issues: they are therefore a vital component of sustainability management

- Metaethics deals with the foundations of the study of ethics while ethics examines the moral act, the source of our morality, and its purpose or role within society

- Two theories dominate moral philosophy today: deontology (rule-following) and consequentialism (the morality of an act depends on its consequences) although mixed views are often held

- Our attitude to morality is strongly influenced by whether we believe it to be subjective or objective

- Adoption of subjective and objective ethical positions is especially evident in cross-cultural situations

- Objective ethics makes the notion of ‘moral progress’ meaningful (possibly as a ‘norm cascade’ based on the ‘excalator of reason’) and it allows for an expanding sphere of moral commonality that can encompass other species and, some might argue, the broader environment

- The relative roles of reason and will (emotion) in moral decision-making is contentious but an appeal to reason is evident in the cross-cultural and religious idea of the Golden Rule

- Utilitarians regard the ultimate purpose of morality (its ultimate value) as universal happiness or human flourishing then this can only occur when humans exist in a harmonious relationship with the environment and this is why animals, plants, rivers and mountains are an integral part of the moral sphere

- Ancient Greek philosophers referred to human harmony or flourishing, the ultimate value of life, as eudaimonia

- The modern word for the harmonious integration of human consciousness with the external world (planet Earth) is ‘sustainability’

COMMENTARY & SUSTAINABILITY ANALYSIS

Today we live in a highly integrated and globalised world of interdependencies where science and technology dominate most of 7 billion human lives in a way that the Greek philosophers could not possibly have imagined. But their question ‘How are we to live harmonious and flourishing lives?‘ is more pressing and relevant than it ever was in the past: it is still the fundamental question of morality and human existence. Does it make sense to speak of an ultimate end or final human purpose (telos) – that to which all humans aim: the attempt to achieve our maximum potential as human beings?

Philosophers and scientists find it advantageous to view the world as objectively as possible because we know that our human subjectivity can interfere with the way we interpret the way the world is. So, we try to see things from, as it were, ‘the point of view of the universe’. From this perspective, with subjectivity removed, the universe just ‘is’. The universe does not have values because values are added by human minds. No ‘ought’ (no values) can derive from the existence of a chair because a chair just ‘is’. Viewed from this detached vantage point humans too just ‘are’ because they, like chairs, are just objects of the universe. Any purpose or value, in such a world, is a consequence of human subjectivity.

But humans, and indeed all living organisms, clearly have ‘interests’ in a way that a chair does not. All life is founded on the assumption of survival and reproduction as an ultimate end. For self-aware deliberating humans this translates into the consciousness categories of happiness, wellbeing, and flourishing. Normative consequences flow from the fact of our living existence unless, of course, we wish to deny our humanity and to become an object in the universe with the same metaphysical quality as a chair. To claim that the fact of life has no implications of value is a philosophical indulgence.

This view of ethics founded on our biological nature is referred to as biological normativity. Since consequentialism in its most popular form as utilitarianism is based on the premise of ‘the greatest happiness for the greatest number’ then consequentialism (unlike deontology or divine command theory) rests on an assumption of biological normativity.

The introduction to this article posed the possibility of a universal and objective moral code that would apply to the community of life, future generations, and the planet. For ethicists the prospect of moral concern for non-sentient objects, like the planet, is bordering on the absurd for a subject that has been confined almost exclusively to humans. We do not include rocks and rivers within our moral sphere because they cannot have interests and concerns and they do not feel pleasure and pain. And yet if we do not care about these things then human flourishing is threatened. Climate change is a good example. Should we care about the quantity of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to the extent that we feel morally obliged to do something about it? The answer must be ‘yes’.

From the ancient Greeks to the utilitarians of today philosophers have suggested that from the many, often trivial, reasons for our many moral decisions and behaviour we can discerned a broad overall or ultimate goal. Though such an all-embracing goal may be ill-defined it can be uncontroversial and therefore acceptable. The ancient Greeks called this overall goal eudaimonia, for Plato this was a kind of harmony within individuals as they cooperated together within a harmonious society. Aristotle saw the goal for individuals as achieving their maximum human potential given their own particular circumstances. Today we use a wide range of loosely equivalent words like ‘happiness’, ‘pleasure’, ‘the common good’, ‘well-being’, ‘human flourishing’, ‘life satisfaction’, and ‘quality of life’ which have been taken up by ethicists and social scientists as general goals for human activity. Utilitarianism, founded on the Epicurean-like ideas of pleasure and happiness and taken up by Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Henry Sidgwick and influential today through the work of Australian philosopher and practical ethicist Peter Singer. Just as ‘health’ is the acknowledged goal of medicine so ‘well-being’ or ‘human flourishing’ is an acceptable ultimate goal for ethics. With human flourishing as a universal goal for humanity it becomes possible, in principle, to develop an objective ethics directed towards this end. There will be those who do not desire such a goal, just as there are those that do not desire health, but these will be few and their existence does not negate the enterprise.

The article on happiness examines in closer detail what it means to be happy in terms of an ethical system and utilitarian ethics in particular. However, the use of a mental state as an ethical goal lacks clarity. The stated formal ethical goal of the international movement for sustainable development initiated by the United Nations is ‘human well-being’ similar to the traditional goals of utilitarian ethics such as ‘human flourishing’, ‘human happiness’. However, the program of international action based around this goal emphasises less the ‘internal’ mental state and more the ‘external’ economic, social and environmental management goals and conditions that are needed to guide humanity in the direction of universal well-being. The philosophy of human well-being does not conflict with existing religions and belief-systems.

What may be termed ‘sustainability utilitarianism’ recognises the congruence between the ancient Greek philosophical state of eudaimonia, the abstract utilitarian mental state of ‘happiness’, and the practical international program instigated by the United Nations to protect and improve human well-being. Sustainability utilitarianism translates the idea of happiness or well-being into a universal objective ethic whose practical program includes the well-being and integrity of the planet, the community of life, and future generations. In ethics, as in science, the inner must adapt to the outer if humans are to survive, reproduce and flourish.

Much of the study of morality has moved out of the realm of theology and philosophy (its traditional domain) into the realm of the psychological and behavioural sciences where some of the most exciting contemporary research is active in new disciplines like evolutionary psychology and moral psychology, not to mention the flood of general knowledge about the structure and function of the brain coming to us from neuroscience in general. Philosophers like Australian utilitarian Peter Singer are concerned with the moral foundations of decisions relevant to contemporary life in the relatively new discipline of practical ethics: issues like abortion, euthanasia, poverty, and genetic engineering. The traditional ancient Greek goal of ‘A Good Life’ can be made relevant to today’s world by providing a program for the well-being of the community of life through the protection of the planet and concern for future generations.

The discussion of ‘nature & nurture’ showed how organism and environment are inextricably intertwined both physically and psychologically as an organism-environment continuum. Though morality is clearly a matter of intentional mental activity we can ignore the integration and dependence of our mental activity on envirnmental factors. Debate about the source of our morality is generally framed in terms of the interaction of the two ‘inner’ (genetic) factors of moral intuition (passion, will) and reason. But this omits or significantly ignores the vital and inevitable role that must be played by the ‘external’ environment. This has a bearing on assessments of the overall purpose of morality.

If we accept the congruence of life-goals and moral goals then we can consider a number of the candidates for this most esteemed role. Plato’s ultimate goal was the ‘Good Life’ which meant harmony and happiness in both society and ourselves and requiring a just person living in a just state. The Greek word ‘eudaimonia’ was used to indicate this state of harmony or ‘human flourishing’. Utilitarians like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, albeit in a different context, but still seeking an ultimate goal for our behaviour, produced a new set of moral objectives: ‘pleasure’ (perhaps following the precepts of Epicurus), ‘happiness’ and the ‘common good’. Today the word ‘well-being’ has become a popular portmanteau term meaning the same thing.

If we accept the applicability of the functional organism-environment continuum then it must be acknowledged that mental states like happiness and pleasure do not adequately convey the necessary and essential environmental component. The ‘common good’ does this job better. Concepts like human flourishing and well-being, though adequate, need fleshing out. What is it in the ‘environment’ that helps to produce a sense of well-being and flourishing? Biologically we can acknowledge that the goal of all life is to survive and reproduce and ‘flourishing’ is an integral part of this. Perhaps the ancient Greeks were nearest by expressing the desire for humans to be in harmony with their environment. But their emphasis was on the human environment and especially the political one.

Assuming that reason has evolved, like our bodies and minds, by natural selection then we can reasonably postulate that it will be orientated towards a single adaptive end – the survival, reproduction and flourishing of the species. We can also specify some requirements to achieve this: firstly, as complete an understanding as possible of the world that is external to our minds (a process that we have called science), and secondly, the making of decisions about our behaviour in relation to that understanding of the external world such that we are will flourish in the future (which we can call morality).

Today we know that our broader environment, the planet (not just people), is necessary for our survival and that the future of the planet’s biodiversity is in our hands. Modern science now shows that future human well-being, the common good, or eudaimonia, will depend on the condition of the planet. The purpose of morality then is the harmonious integration of humans with their environment. The word of today most closely approximating this idea is ‘sustainability’ and for this reason planet earth is now included within our moral sphere. This kind of morality is not the result of introspection and inner states like pleasurable happiness, it is based more on ‘outrospection’ or integration with the external world … not emotional empathy but cognitive empathy.

Human happiness as an ultimate value must take account the organism-environment dependency. Well-being involves more than a mental state it entails the integration of subject and object, humanity and the world. Social progress is a difficult idea since it calls into question the embedded and questionable values like those of nineteenth century colonialism a associated with moral ‘improvement’. Some common agreement may be reached by adopting a point of generality that will find near-universal acceptance. On this web site and elsewhere such a starting point can be found through the general moral notion of human flourishing or well-being. Such an idea is congruent with both the moral principles of utilitarian ethics and practical United Nations programs dealing with developing nations. The Social Progress Index (and similar indices) flesh out what is meant by human flourishing and happiness (see Morality & sustainability) using social rather than economic metrics by calculating the well-being of a society in terms of social and environmental outcomes. The social and environmental parameters include personal safety, ecosystem sustainability, health, shelter, sanitation, equity, social inclusion, personal freedom, and choice. These factors are uncontroversial and clearly take economic circumstances into account.

Human happiness or well-being as described here is therefore taken to entail a relationship between humans and their environment: that a state of harmony between the community of life and the environment cannot exist when this inter-relation is dysfunctional. That the changing human condition both directly and indirectly drives change in ecosystems and with changes in ecosystems comes change in human well-being. While also recognising that many other factors independent of the environment change the human condition,and many natural forces influence ecosystems.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2000) [8] provided a clear outline of the relationship between humanity and the planetary environment, pointing out how human well-being depends on natural resources or ‘ecosystem services’ and how demand on ecosystem services is rapidly increasing and sometimes outstripping capacity.

Critical to our well-being are the links between environmental management, poverty alleviation, and sustainable development. This points to the importance of consideration of biodiversity and ecosystems and the elaboration of an environmental ethic.

(Scientifically we must consider organisms and their behaviour, including mental states, as a result of organism-envitronment interaction, an organism-environment continuum. This can inform the important discussion about subjective and objective ethics.Reason and evidence are the only way we’ll ever cut through the mess of conflicting gut feelings and moral intuitions. One way of viewing our behaviour is as a complex mixture of feelings, values, emotions, prejudices, desires and so on. This may be the source of our passions and will but, as Plato would probably claim, morality is the application of the moderating and taming power of reason. Indeed, we may define morality as the application of reason to appetite.)

Citations & notes

[1] The distinction between ethics and morality is subtle and not important here

[2] Even so, claims for self-evident truths and inalienable rights run into difficulties. Ideals of equality for example can and do infringe on ideals of liberty. Inalienable or inviolable rights seem to require considerable amendment for their many exceptions

[3] Singer, P. Practical Ethics. Third Edition. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

[4] Most of our behaviour is proximate or instrumental, that is, it is directed to achieving a multitude of different goals. An ultimate goal, like happiness or The Good, is a non-instrumental or intrinsic good: it is an end in itself and the final point of all our instrumental behaviour. The ultimate goal is where the trail of repeated questions ‘but why did you do that?’ comes to an end

[5] cited in De Lazari-Radek & Singer, p. 14

[6] cited in De Lazari-Radek & Singer, p. 43

[7] Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900 ) educated at Rugby, was a moral philosopher at Cambridge from 1855-1900 at a time when Fellows of the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford received their posts only after a formal acceptance of the Church of England’s central doctrines, and when women were not allowed to attend the university

[8] see http://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/Index-2.html

[9] see The Great Debate – Can Science Tell Us Right from Wrong? http://thesciencenetwork.org/programs/the-great-debate

[10] Libertarians, like political philospher Rawls, rank liberty higher than happiness

[11] Interpreted in many ways, happiness being, for example, the exercise of virtue according to reason

General references

De Lazari-Radek, K. & Singer, P. 2014. The Point of Vew of the Universe. Oxford University Press: Oxford

Singer, P. 1981.The expanding Circle: Ethics and Sociobiology. New York

De Waal, F. 2013. The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates. W.W. Norton: New York

Excellent sources of general reference on the web include the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy and The Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (see for example ‘Environmental Ethics’ in both)