Reason – Test

The fact that you are even prepared to read this article presupposes that you are open to reason. Reason is taken for granted in our communication and crucial when we are trying to provide accurate explanations or persuade people to our point of view.

Reason uses the senses and allows us to form mental categories, propositions, and inferences. We cannot intelligibly ask the question ‘Why be rational?‘ because the question presupposes the necessary use of rationality in providing an answer. This simple logical point about communication was most clearly stated by Aristotle over 2000 years ago in his Principle of Non-contradiction – that contradictory statements cannot both be true in the same sense and at the same time

You might disagree with some of the things I am about to say in this article, but if you want to change my view you have only two alternatives – either some form of mental or physical violence, or persuasion by reason.

Reason tells us that in the long-term violence is not good for us, either as individuals or communities. So let’s all accept reason as the key to mutual understanding … ?

Strangely, we do not discuss this fundamental intellectual tool much. Perhaps we suspect its merits may be over-rated or illusory, or maybe the literature about reason rapidly becomes academic, specialised, and demanding. However, because reason is so basic to communication and a vital attribute of human nature, and also because it is an exciting part of current scientific research (and since I deploy it as a major tool on this web site) – it deserves some attention here.

Reason as a human universal: innate and a priori

Possession of reason must be at the top of the list when we ask why humans are the dominant life form on planet earth. Reason is the ultimate human tool behind human civilization so we need to know as much as possible about how it arose and how it works – its potential and limitations.

Aristotle described humans as rational animals, reason being a universal characteristic of our species and one that makes us unique: it is a part of our human nature being hard-wired into our genetic makeup. We do not learn the capacity for reasoning (although we do learn how to use it to greatest effect), we simply have the capacity for reasoning: it is what the philosopher Immanuel Kant called a priori – an ability that we have independently of experience.[10] Reason is a faculty of our cognitive awareness that is neither sense-perception (we can think beyond what we can perceive) nor an affect (feeling or emotion); it is not a mystical or spirit-like inhabitant of the mind, and it can be affected by drugs and injury.

Reason is the way we consciously make sense of the world – it gives structure to the flood of sensory impressions that pour into our brains and thoughts to proceed in a coherent way, allowing us to create imaginitive futures as a precursor to action. Reason relates the concepts and categories produced in the brain, noting similarities and differences and helping us to function in the world. Using logic and evidence we can do science and justify or change the practices, institutions, and beliefs that underlie our individual and social behaviour (see Science & reason).

As an evolutionary trait its time of emergence may be dated to about 70,000 BP, a period associated with the development of language and sometimes called the cognitive revolution.

Origins of reason

Mental states and attributes, like physical traits, did not spring fully-formed from nature, they arose by a process of gradual change. Reason emerges in a primordial form in the teleological functional design we see in living systems as a consequence of natural selection – it is the way that adaptations, as mindless mechanical causation, manifest the fundamental axiom of living systems, which is survival and reproduction. From this axiom derives the inevitable conclusion that living organisms have ‘interests’ (as factors that promote survival and reproduction) even though most are unaware of those interests. This is as true of plants as it is of humans and it is not only the rudimentary source of reason but a first step on the path to ethics and meaning. Reasons (functions, purposes, goals) exist in nature independently of observers and gods. Spiders build webs for a reason, even though they know nothing about that reason. Reasons lie within nature itself, they are not read into nature by the human mind, they are not metaphorical reasons. Aristotle‘s teleology was correct. We see a gradation of natural reasons as we move evolutionarily to sentient organisms. We can see the reasons for the complex mating rituals of birds and all manner of instinctive animal behaviour. But because we can see the reasons for their behaviour (and the animals cannot) does not mean that the reasons are a product of the human mind. Rudimentary reason exists in nature itself.

Reason & representation

Other sentient animals are largely bound within the present moment. The highly developed processing power of the human brain gives us imagination – the ability to consider both past and future, objects that are distant from us, counterfactuals, and abstract ideas – which gives us greater comprehension. Though reasons are present in the world, only humans represent reasons and values to themselves and one-another as they deliberate. Humans can look back at evolutionary history to see the many reasons (purposes) that existed in mindless nature. We treat reason as a faculty unique to humans, it is what gives us forethought, hindsight, and abstraction but it arose out of the reason in nature.

Reason in operation; the conceptual faculty

Through language reason allows us to share knowledge and culture, also to innovate through the use of our imagination which also allows us to relate concepts and to plan the future.

Language, like reason, is cited as a defining human trait it is not the words and sounds of language that generate its power but our ability to link words to meanings and concepts. Reason develops concepts based on percepts (the input of perceptions, sensory data that is concrete and particular) converting this into general knowledge. For example, the conceptual faculty allows us to derive a universal concept (and word) ‘tree’ while observing individual trees; it also allows us to generalise from individual cases to general laws, theories and principled systems as it does in science and mathematics, by means of inductive reason; and it allows us to establish complex causal relations. A sentence like ‘humans are rational animals’ has not only a complicated grammar and syntax but it contains concepts like ‘reason’, ‘human’, and ‘animal’ which we can only understand in terms of yet further concepts.

Reason connects and relates a vast network of interwoven and interdependent concepts in a way that enables us to deal with life, to survive and flourish.

Volition (willpower)

Reason sifts and sorts the mass of sensory data pouring into our brains by creating increasingly abstract categories. Much of this goes on subconsciously but it is possible for us to become self-aware by using mental focus and selective perceptual attention. While we are driving much of what we are doing is intuitive or automatic, but we also need to be responsive to danger and this means concentrating and being ready to respond, to rapidly bring our selective perceptual focus to bear on each particular situation. We can also introspect or increase our internal or rational conceptual focus, as we do when reading, doing maths, making choices, and using our willpower to be purposeful in some way. Cognitive scientists sometimes refer to this as System 2 thinking in contrast to System 1 thinking which is more or less intuitive.

Self-correction

Above all reason makes conscious self-correction possible. This conscious capacity for self-correction closely resembles the unconscious and mechanistic teleonomic process of natural selection, the process of ‘self-correction’ or ‘trial and error’ that is the basis of evolution (see Purpose). Indeed, we might conclude that reason is our only conscious means of self-correction, it is the capacity to respond to life situations by understanding the relationship between cause and effect rather than responding intuitively to it.

Faith in reason

We place great hope in reason as a means of solving problems not only through its application in science and technology (see Reason & science) but also as a guiding principle of morality (see Reason & morality) and indeed all aspects of our lives. A completely irrational mode of existence is difficult to imagine.

But is our faith in reason justified? After all, what happened to your sensible rational New Year’s resolution?

Our attempts to lead rational lives can quickly dissolve. What exactly is it that goes wrong when our carefully constructed plans and intentions go astray? Here is a questions that has challenged the world’s greatest minds: what is the relationship between rationality and other aspects of our mental life?

Let’s first explore some of the historical and philosophical background to contemporary research into reason, the mind, and human nature.

The Enlightenment & after

Without doubt the period in history that placed greatest emphasis on reason was the 18th century in Europe, the ‘Age of Reason’. In a burst of scientific activity and world exploration the European mind was invigorated by the the discovery of new peoples and cultures, and the marvels of nature in previously unknown or unexplored parts of the world. After the despair of years of war and conflict intellectuals optimistically believed that new freedoms could be achieved through the rigorous application of science and reason to human affairs pointing out, for example, that the so-called self-evident truths of the day – the claims of faith, tradition, dogma, and the divinely-ordained political authority of kings and queens – were not self-evident at all, but simply unjustified ways of retaining power. It was time to transfer the powers and privileges of absolute monarchs to people lower in the social hierarchy.

The hoped-for smooth and rational transition did not occur. Social power would not be given up easily, even to reason. In France, home of Enlightenment thinking, the French Revolution of 1789 involved the vengeful beheading of the king and many others: it was a time of fanaticism with raging mobs and a period of anarchy that, in France, became known as ‘The Terror’ in a pattern of social upheaval that has been repeated again and again. Loss of life in France between the start of the French Revolution in 1789 and the end of the Napoleanic Wars in 1815 totalled about 4 million people.[3] The French, American and subsequent liberal democratic revolutions in other countries have given rise to stable modern democracies but this has often been a painful and bloody process.

The 17th to 19th centuries had seen a period of European imperial expansion by Enlightenment-educated gentlemen who colonised the world believing in their congenital superiority to other races. Europeans were convinced that, unlike indigenous peoples, they were ‘civilised’ and that native peoples needed ‘moral improvement’. A great sense of progress swept through European society and its colonies as it spread triumphantly across the world. In spite of set-backs Enlightenment optimism had removed the spurious authority of God and monarchs and produced a revival of ancient Greek humanitarianism, a confidence and optimism about human artistic, scientific and political potential. This was a time for ‘the people’.

Then, in the first half of the 20th century the world was engulfed in two world wars as the ‘most civilised peoples’ engaged in history’s greatest ever period of blood-letting during which more than 70 million people died in the mass slaughter. Eighty percent of Jewish people were exterminated in World War Two. Confidence was replaced by total disillusionment. Enlightenment ideals now seemed like total folly. Science had produced the atrocities of modern armaments and the barely imaginable destructive power of nuclear bombs. How could belief in humanity possibly be sustained? Following a tradition that glorified the honour, valour and courage of armed combat the youth of Europe had rushed to be part of the glory of brief wars. Now the call was for the ‘death of glory‘ and a desperate wish, so often made, that World War Two would be the ‘war to end all wars‘.

There was little to be said and even less to believe in. After the bloodshed of two world wars what possible credence could be given to any new optimistic political ideology or grand intellectual theory about humanity or society? All that was left was the stark reality of human ignorance and irrational brutality.

Shakespeare, that brilliant commentator on human nature, expressed the jaded world-wearinesss associated with misplaced optimism about humanity in these words:

I have of late—but wherefore I know not—lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises, and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy, the air—look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire—why, it appears no other thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors.

What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world. The paragon of animals. And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me. No, nor woman neither . . .

Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2

If you press someone you know for an explanation of such monumentally destructive and apparently irrational behaviour as the two world wars they will probably look embarrassed. This is not the sort of question we generally ask. They may well shrug their shoulders and say something like ‘I suppose it is human nature‘.

We are surely driven relentlessly to this conclusion. Warfare continues to this day. Atrocities in war are rarely confined to one particular side. Given the appropriate circumstances we are all capable of behaviour which, in retrospect and with the use of reason, we would not repeat. The people engaging in the two world wars were very like ourselves. And genocidal wars did not end with World War Two.

We are still feeling the effects of this total social breakdown.

Reason can fail us in the heat of the moment when we need it most: but it can also be used later to reflect on events, their causes, and ways of making things better in future.

This is a good place to start a discussion of reason – with the tensions that occur between our simple rational desire for happiness and order, and the forces that override these noble intentions – negative emotions like like anger, fear, hate, greed, and jealousy that can quickly take charge.

How have thinkers down the ages explained this apparent conflict in human nature, this ‘divided self’?

Ancient Greece

For a more extended treatment of Plato’s views see Socrates, Plato & Aristotle.

Ancient Greek philosopher Plato believed that we all desire harmony and happiness in both society and ourselves: this is what he famously called ‘The ‘Good Life’. But to achieve this harmony required a just person living in a just state. To become Just or ‘harmonious’ Plato believed that we must reconcile three competing aspects of our mind (or ‘soul’ as he called it). These key elements were reason (logos), will or spirit (thumos), and appetite (epithumos). Reason could be satisfied by wisdom and logic, spirit satisfied by honour and courage, and appetite or desire satisfied by temperance and moderation. However, overall harmony could only be achieved when logos prevailed over the other elements, especially appetite.

Morality (the Good) was absolute, objective and knowable through the use of reason and logic. For both individuals and society to flourish and be harmonious (the Just individual in the Just society) reflective judgment (reason) must guide the will, intuition and appetite as we endeavour to put into practice the four cardinal virtues of wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice.

Some thinkers after Plato & Aristotle

Plato had claimed that the most important knowledge guiding our behaviour was absolute, timeless, and certain like that of mathematics (it had nothing to do with misleading sense-perception). This view became known as philosophically as Rationalism. For Plato’s student Aristotle reality lay in the natural world, not in some abstract realm. Reason depended on sensory data, and mathematics was an extrapolation from observations based in the physical world such as our learning to count, and this was also true of logic. Aristotle’s point of view became known as Empiricism.

Medieval Christian scholastic theologians that followed in the wake of the Greek and Roman Empires were perplexed by the many and conflicting views bequeathed to them by the ancient world which had placed so much emphasis on reason. They concluded therefore that reason cannot give us certain knowledge, only faith can do that. Not until St Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century would reason be reinstated as a respected mode of thought, Aquinas pointing out that only through reason could humanity understand the wonder of God’s Creation.

In the Early Modern period (15th to 18th centuries) the old debate about Rationalism and Empiricism was reignited. Since at least Plato some philosphers had maintained that reason can give us a description of the world that is uncontaminated by illusory experience, like a God’s-eye impression of reality. Empiricists viewed this as a vain hope, knowledge comes ultimately from experience alone and therefore there is no possibility of separating knowledge from the subjective knower. Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) claimed that mathematics and logic only described ‘relations of ideas‘, not truths about the world (‘matters of fact‘). They could only tell us about the operation of our language and its various conventions and definitions. ‘All knowledge is empirical‘ said Hume, and it could therfore not be wholly trusted. Inductive generalisations on which much of our knowledge rests (including that of science) cannot be justified by logic – the future cannot therefore be guaranteed: because the Sun has risen in the morning every day of our lives does not logically guarantee that it will always do so (this particular philosophical view became known as Skepticism). Necessity, thought Hume, is a product of thought, not the world, it merely reflects the ‘relations of ideas‘.

Hume also confronted the old problem of the divided self. He reduced mental conflict to two entities, reason and the passions (or will). Reason alone had no motivating content, it was the will that provided the trigger or stimulus needed for action. Hume maintained that, for example, we cannot from a particular state of affairs, make a moral judgment without input from our will, a conclusion summarised in his famous statement that ‘reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them‘ and his assertion about ethical propositions that ‘you cannot derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’‘. Following from this came his second assertion that the moral sentiments that guide our lives are not to be thought of as rational propositions but expressions of approval or disapproval, an ethical position known today as emotivism (the role of reason in ethical systems is discussed further in Reason and morality.

German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) broke the deadlock between Rationalism and Empiricism by suggesting that we need both. Experience provides disorganised content, reason provides structure but without content. The world we know through our senses and reason is not the ultimate reality but a man-made construct, an internal experience in which the appearance of things is shaped by our minds which act like a kind of sensory filter. Kant recognised a link between the mind and the external world but this was like a common inter-subjectivity – an agreement about the world among people with similar minds and consciousness.

Modern science

Following general philosophical speculations about the mind like those of Plato and Hume came more applied forms of analysis like that of Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Based on his study of mental illness Freud proposed a tripartite mind (not equivalent to the Platonic version) which consisted of unconscious basic instincts (id) that dominated early life, but also the self-aware consciousness (ego), and the conscience as an internalised regulator of behaviour (super-ego). Freud drew special attention to a psychological world that we cannot access directly – the dark recesses of the unconscious mind its possible influence on our behaviour.

Now well into the twentieth century the mind was still a largely scientifically unexplored region. There were the speculations and theories of highly intelligent men concerning its nature and operation and its relationship to behaviour, but none of this knowledge had been subjected to extended peer-reviewed scientific experimentation and analysis. Psychology was a newly-emerging subject and the scientific understanding of mind would not gather momentum until after the mid twentieth century, that is, after World War Two.

The last fifty years have seen an explosion of research ito all aspects of the mind. Wkipedia today lists more than 50 empirically-based disciplines examining the structure and function of the brain and its connections to behaviour. Only a few decades ago there was serious debate concerning the independence of the mind from the body, sometimes referred to as the ‘ghost in the machine’, a modern echo of Plato’s ‘soul’. Today, in spite of the deep complexity and philosophical difficulties still shrouding the mind, few would divorce the mind from the physico-chemical processes that occur in the brain. Though we are still struggling to understand our ‘divided selves’ the place of reason in our mental lives has now been transferred from the realm of speculation and metaphysics into the arena of science.

Our understanding the operation of the brain in cognition and perception, its evolution and functional partitioning, the physical operation of neural networks, the role of innate mechanisms, and at the social level of our general behaviour – all have come a long way. Evolutionary psychology is looking at the long-term origins of human behaviour, our emotions, and morality as Darwin had wished to do – although evolution of the mind and behaviour is still struggling to gain the acceptance that evolution of the body has received. moral psychology is now investigating the sources and processes of our moral behaviour, the possibility of an innate moral sense as a source of our moral intuitions. At least five moral ‘senses’ have been postulated and these are all the subject of current research, they include: reciprocity, altruism, selfishness, cheating and free-riding, our propensity to respect authority, the feeling of disgust, mistrust of strangers, observation of codes of honour and loyalty, and possibly more.

So what does modern science make of the divided self?

Dual process theory

We now know there are significant differences in the operation of the left and right sides of the brain. We can also distinguish the ‘old brain’ (the brain-stem region considered to remain from our earlier evolution: the major site of our instincts and impulses), and the ‘new brain’ (the pre-frontal cortex which is where most of our reasoning occurs).

Psychologists like Kahneman suggest a dual process model for the brain (see Kahneman, 2013) as a way of characterising the issues we are discussing. On the one hand we have an innate cluster of moral impulses and intuitions that we use to make quick decisions. This system allows us to effortlessly survive from day to day in a complex world by means of rapid pattern-recognition and response … the way we, without concentrating, literally (and extremely usefully) see the world as discrete items rather than a meaningless mixture of colours and textures. This he calls System 1. However, we also have the capacity to consciously abstract ourselves from situations and consider them in a more detached way, which he calls System 2. Our moral intuitions, grounded in our evolutionary biology, can be modified or ‘trained’ through both cultural norms and individual experience.

System 1 – Intuitions & Impulses – holistic processing is based mainly in the brain stem: it is unconscious (no sense of voluntary control) and ; it is automatic, impulsive, intuitive, effortless, efficient, fast, and generally reliable – and it works by processing patterns or relationships and completing many tasks at once; it is heuristic. Moral psychologist Josh Greene has compared this to a camera on ‘automatic’.

System 2 – Reason & Deliberation is based mainly in the pre-frontal cortex: it is conscious and requires effort; it is calculating, flexible and analytic, centred on single objects and attributes and proceeding one step at a time, and involves a sense of agency and choice, and it entails concentration.

Most significantly System 2 reasoning (our conscious reasoning faculty) is influenced by rational persuasion and requires concentration that can be interrupted, while System 1 reasoning and thinking (perhaps better termed intuition, involves innate skills that we share with other animals including our structured perception, object-recognition, attention-orientation, universal affects (like the fear of spiders). By programming attention and memory System 2 can train System 1 to adopt new habits. System 2 is our self-control which monitors and generally has the last word on System 1 although System cannot be ‘turned off’. System 1 has greater influence when System 2 is busy as though there is a shared pool of mental energy, and System 2 often endorses or rationalises ideas and feelings generated by System 1.

Many interesting observations have emerged from this model. For example, evidence suggests that in tests Easterners (Japanese) are more holistic in their thinking while Westerners are more analytic. This is essentially a learned, not genetic, trait and it demonstrates how cultural environment can play a role in our general outlook and how so much of what we understand about life comes from people who are WEIRD (western educated industrial rich democratic).

Recent research has also focused on the many ways in which our reason can falter.

Irrationality and self-deception

If we accept that being more rational is a worthy pursuit then we need to be ultra-aware of situations where our views may become prejudiced in some way. This has been the subject of recent research which has thrown light on a multitude of what have become known as cognitive biases.

We know that our emotions can get the better of us … when we lose our temper, make statements that we later regret, or get overpowered by fear or jealousy. We can give in to peer pressure, the desire for power or an inner need for the respect of others. In particular we are all selfish (this leads to a kind of rational paradox – because being selfish, though unfair, seems a rational position to hold). But irrationality can arise in many ways – it is not simply a matter of our emotions taking over.[15]

Framing effects – reacting differently depending on whether a choice is presented as a loss or as a gain (we give greater value to something we own than the same that we do not: difficult choices involving life and death of large numbers of people will vary depending on whether the results are presented as ‘people that live’ or ‘people that die’: more people support the same economic policy when it is expressed in terms of the employment rate rather than the unemployment rate)[4]

Confirmation bias – we give greater credence to views and data that confirm our existing beliefs or which are easier to imagine[5]

Base-rate neglect – only taking note of prevailing information or giving undue weight to something without realising it (because the daily news contains mostly violence we assume the world is more violent today than it was in the past: because a tossed coin has come down ‘heads’ three times in a row we assume there is no longer a 50/50 chance it will come down heads on the next toss, this being known as the gambler’s fallacy).

Priming Preceding a question with a loaded fact like telling air passengers of a recent plane accident before they undertake air travel.

Physical conditions – opinions can be influenced to some extent by internal and external physical conditions: room temperature, hunger etc.

Natural & unnatural – unwarranted trust of natural things and mistrust of man-made things.

Familiarity – we judge the familiar as less threatening.

Biases like these have been called cognitive illusions since we are so easily taken in by them … but they are much more difficult to detect and deal with than perceptual illusions (like straight sticks that bend when poked in water).

In our daily lives as in our science we proceed by inductive inference, on conclusions based on probability – in other ords what, from our experience, we think is most likely to happen in a particular situation. How good are we at estimatin randomicity and risk? Psychologists have discovered that we are not very good at this and that the content of both inductive and deductive reasoning can significantly bias our decisions.[11] For example, although the statement ‘a bachelor is an unmarried man’ is deductively beyond dispute there are many social contexts where our use of the word ‘bachelor’ does not share the clarity of the apparent logic so, for example, would you use the word ‘bachelor’ in the following situations: a man in a gay relationship; a 75 year old unmarried vicar; a 13 year-old playboy with a thriving business; a man in a de facto relationship with two children … and so on.[12]

We may have irrational fears (of, say, harmless animals); we tend to get hooked on needing more and more of something pleasurable in order to satisfy our desire (known as the hedonic treadmill); we tend to take a small reward now in preference to a larger one later; we make decisions about complex things by simplifying them in our minds (known as heuristic substitution).

One pervasive bias relates to the Golden Rule (‘do as you would be done by’) and a rational paradox. We are naturally selfishness, putting our own interests above those of other people – a tendency called first-person exceptionalism. And yet self-interest seems in many ways a very sensible and rational position to take.

How do we know if we have an irrationality problem?

Hard-nosed slef-conscious irrationality, as dogmatism, is manifest in several ways: anger at well-articulated alternative views; the holding of opinions without evidence; the condemning of other opinions without being able to articulate their main contentions and the reasons why they are maintained; constant seeking out of people and sources that reinforce your particular beliefs; and (sadly) the assertion that those who do not hold a particular view are evil.[3]

Becoming more rational

‘If you don’t want to be a victim of your genes be rational’[5]

Becoming more rational means believing it is more important to have an accurate view of the world than to win an argument. This is easy to say but difficult to put into practice because it requires putting aside both our emotional attachment to our beliefs and our ego attachment to winning a point in dispute (called ego validation).

Here are six strategies to help out: think of an argument as a collaboration rather than a combat – together you are working towards accuracy; imagine your belief as an object away from yourself; visualise being wrong and its consequences, this assists your frame of mind; congratulate yourself on being ‘objective’ not on being ‘right’ thus redirecting the competitive instinct; if you have negative feelings towards someone – imagine their words in the mouth of someone you respect; take the long view – even if you ‘lose’ an argument you have gained a new tool on the path to accuracy.[4] Needless to say, the use of abusive, inflammatory, insulting, or denigrating language will reduce the likelihood of achieving a satisfactory result for either side of an argument.

Obviously a major source of cognitive bias lies in our biology and is related to emotions like fear, jealousy, peer pressure, and a consuming self-interest. Though some of this may at one time have had adaptive value, collective decisions at the global level are, nowadays, having global consequences. The more we are aware of our cognitive biases the better.

There are other tools to helping us overcome our irrationality that are part of cognitive psychology: by writing down commitments or making them known to other people[6]; restricting access to unsettling factors; reinforcing desired behaviour; planning; increasing the utility of the desired goal and reducing the appeal of its alternative.

Cognitive biases

The ideal of rational behaviour (as behaviour directed towards human flourishing) is compromised by many cognitive traits that served us well in the past, but which are not appropriate for life today. These are generally known as cognitive biases (where inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion). Cognitive biases can be organized into four categories: those that arise from too much information, not enough meaning, the need to act quickly, and the limits of memory. A full list of these, with discussion, can be viewed in Wikipedia under ‘List of cognitive biases’. A few of those of special interest to articles on this site include:

Confirmation bias– interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses, The effect is stronger for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs. A variant of apophenia, the tendency to perceive connections and meaning between unrelated things.

Negativity bias – we have a better recollection of unpleasant memories than positive memories

Ideology

Most of us hold very dear our grand narratives, especially our social, political, and moral opinions. What would it take for you to change your mind on such matters?

This is not a straightforward question but we must surely admit that evidence must play a major role in any change.

Those who do not accept compelling evidence we speak of as being either ‘irrational’ or, a more emotive term, ‘dogmatic’. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that greater social progress could be made if we made more effort to try and be more impartial in weighing up evidence for and against our basic assumptions.

Rationality is both confronting and hard work because it means that we cannot always end up believing what we want to believe – and that is emotionally and intellectually stressful.

As every scientist convinced about the evidential base of human-induced Climate Change knows – simply producing compelling evidence does not win the day. Certainly there are many ways of dealing with climate change: that is uncontroversial. But how can we possibly deny the science when more than 90% of a large number of the world’s best climate scientists say there is more than 90% chance that there is human-induced climate change? Where is there a higher authority? How could we, as individuals, possibly know better?

Though there are many and complex social reasons for resisting compelling scientific evidence there are clearly many people who do not believe that rationality and scientific evidence are very important.

Commentary & sustainability analysis

This article was written to examine the role that reason plays in the way we perceive and understand the world around us. So much of our lives becomes routine that we forget how human advances in understanding have come through the rigorous and highly disciplined application of reason and how, once reason has provided useful explanations and structures of thought, these can provide foundations on which to build.

The critical mind always demands justification for reasons. On what authority do you say this? It always helps to know the source of authority because that is a clue to its reliability. Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker lists various notoriously unreliable sources of authority: ‘faith, revelation, tradition, charisma, intuition, social authority, mysticism, and the interpretation of sacred texts.’[16]

Historical legacy

Reason permits conscious self-correction and in this it complements the unconscious self-correcting character of natural selection and adaptation. ‘Reason can always stand back, take note of a flaw, and revise its rules so as not to succumb to the flaw again‘.[2] Reason looks towards ‘best explanation’ and it has provided us with the set of categories that we use to explain the structure and process of the physical world, that is, with our science.

Ancient thinkers like Plato and Aristotle draw our attention to the primacy of reason in the construction of intellectual frames of reference whether ‘transcendental’ or ‘scientific’. In Plato and Aristotle, the Rationalist ‘transcendentalist’ and Empiricist ‘scientist’, we have examples of grand narratives of the kind that appeared across the world in the Axial Age and which are still present and obvious in the modern world.

But reason is only one part of our mental life and it is not always in charge. This is both a scientific puzzle and source of material for the arts as they explore the creative, imaginitive, uplifting and destructive aspects of our desires, needs, passions and fears (epithumos) – including the negative emotions like revenge, jealousy, hatred, and bitterness.

The puzzzle of the mind

Humanity has always struggled to understand the operations of the human mind, often with the hope of minimising its destructive capabilities. But until recent times the mind was closed to science: it was an unknown black box, inexplicably complex, and a sacred repository for the soul. As an unknown frontier it has also been the source of philosophical questions, conundrums and ambiguities that have long plagued our thinking: nature and nurture, innate and learned, nature and culture, determinism, free will, skepticism, solipsism, rationalism and empiricism, idealism and materialism, mind and body, the question of other minds, essentialism, instinct and intelligence, phenomenology, scientific realism, consciousness and much more. This parade of arcane words represent ideas that have exercised and bewitched some of the most brilliant brains in the world. Such questions may still not have simple explanations and answers but in the last 50 years we have seen a definite movement of such problems out of the domain of metaphysics and into the domain of science. In particular major headway has been made in our understanding of human nature and through this particular understanding comes the potential for improved self-management.

Modern science

Science is now probing the broad field of human nature from many directions, especially those aspects of our nature that get us into strife. The 1960s and 1970s were a period that might be called the modern cognitive revolution. Neuroscience has made major progress in unravelling the relationship between structure and function in the brain. Evolutionary psychology (gathering momentum in the 1980s along with the affective revolution of the 1980s with its increase in research on emotion) explains why we exhibit the behaviour that we do; behavioural genetics (gathering momentum in the 1970s) now gives us some quantitative assessment of the relative degree to which behavioural traits are under genetic and environmental control; moral psychology (the relation between morality and emotion from the 1980s to 1990s and increasing to the present) examines moral intuitions and moral reasoning across cultures and in relation to the findings of subjects like evolutionary psychology, behavioural genetics, practical ethics, and other behavioural sciences.

Ethics

Collectively new sciences of the mind are opening open up the possibility of moving towards greater moral agreement on what constitutes desirable and undesirable behaviour, a widening of the circle of moral empathy. In spite of many barriers and deficiencies it seems that reason is our only hope for settling differences of opinion. In our daily lives we surely need rational political, economic, social and personal decisions based on the best possible evidence available, even when are reason can lead to different conclusions. We know that persuasive orators can change opinion by appealing to our emotions. The only alternative to beliefs held with good reason is beliefs held without good reason and blind faith, meeting different blind faith can lead to uncompromising confrontation (probably greater than that resulting from differing rational positions).

In retrospect it is clear that human scientific and moral history can be legitimately viewed as a history of error (. Since most of today’s scientific, moral and historical conclusions will, in the future, be viewed as mistaken then to imagine that today we are ‘right’ is hubristic in the extreme. That being said, in life we are condemned to act: we cannot act assuming that what we are doing is wrong. Perhaps our arrogance and certitude,[13] is an innate adaptation allowing us to act with confidence rather than with the justified uncertainty that would paralyse us. Though we must act with conviction, honesty about our fallibility might suggest that this be done with some humility. And though we may be wrong, we can hope that we are less wrong than we were in the past – that we are making progress.

What about sustainability?

Well, reason and passion surely combine to favour the Platonic desire for harmonious individual and public lives, for what the ancient Greeks called eudaimonia: today we use words like ‘well-being’ or ‘flourishing’ or ‘the common good’. The attempt to convert abstract ‘well-being’ into a practical and considered program of human improvement and progress we call ‘sustainability’. And it is reason that makes conscious self-correction possible.

We try our best to base morality on reason. But reason, as Liebniz observed, tries to view the world from ‘no point of view‘. We cannot achieve this ideal of reason because we are living organisms. The goal of all living organisms is to not only survive and reproduce but to ‘flourish’. We may claim like Plato that this is a universal, objective and eternal truth – a goal that can justly be given the title ‘the meaning of life’ (see Meaning & purpose).

Reason, as the ultimate human tool evolving out of the self-correction algorithm of natural selection, has given humans the capacity to (however precariously) dominate all other organisms on the planet and to occupy and exploit all continents. The future, reason tells us, is not necessarily all rosy: we will need reason to help make it more secure for the community of life.

Key points

- Humans are rational animals, reason being the ultimate tool enabling the uniquely human characteristic of civilization (language, religion, science, law, the arts, mathematics etc.) that has allowed us to proliferate, dominate other organisms, and spread to occupy all parts of the planet

- Reason is an innate evolutionary trait that became manifest at the time of the cognitive revolution about 70,000 years ago

- Reason is fundamental to all communication (especially scientific explanation) but its relation to other, sometimes competing, aspects of the mind is only just becoming scientifically understood

- The central role of reason in guiding our understanding of the world, society, and our own minds was clearly articulated by ancient philosophers like Plato and Aristotle

- Reason exists in an uneasy relationship with our emotions (the will)

- Reason allows for self-correction and in this way it differs from tradition, dogma, and faith which constrain the free use of reason. Reason can be very similar to natural selection as a form of fine-tuning using feedback

- In its capacity for conscious self-correction reason resembles the unconscious ‘self-correction’ of natural selection

- Science is reason applied with maximum rigour within the domain of scientific activity

- The place of reason in the mind and its role in human affairs are being elucidated by neuroscience and cognitive science but more specifically by evolutionary psychology, moral psychology, and practical ethics

- Reason must play a critical role in securing a sustainable future in which the community of life may flourish

Australian Coins

Though the ancient Greek philosophers placed great emphasis on the use of reason in daily life, they knew that this was not a simple matter. History shows just how difficult being reasonable has proved to be (see Reason).

Can reason alone provide motivation for action … is it reason that drives our moral behaviour or is it our moral intuitions (our beliefs and desires – our will) as Enlightenment philosopher David Hume claimed? Is an objective reason always accompanied by an intuition or are desires something that is ‘added’. Are rationally binding rules like the Categorical Imperative (behave as if to universalise your behaviour) independent of the will as Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant claimed?

Is it correct that ‘appetite’ our will, passions, and desires determine the content of our attention, while reason refines it appropriately to achieve rational ends?

Questions like these are still controversial as moral philosophers, moral psychologists and others take one side or the other.

This article looks at this problem in more detail.

David Hume on reason and the passions

Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) confronted the ancient Greek problem of the divided self directly. Insofar as mental conflict entailed two entities, reason and the passions (or will), Hume pointed out that reason alone had no motivating content, motivation came from the will; it was the will that triggered action not reason. So, Hume maintained, we cannot from a particular state of affairs, make a moral judgment without input from our will, a conclusion summarised in his famous statement ‘reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them‘ this claim often further associated with his assertion about ethical propositions that ‘you cannot derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’‘. Following from this came his second assertion that the moral sentiments that guide our lives are not to be thought of as rational propositions but expressions of approval or disapproval, an ethical position known today as emotivism. Hume’s distinction is at the heart of lively philosophical debate concerning fact and value, science (what ‘is’) and ethics (what ‘ought’ to be). How ‘real’ is this distinction?

This matter remains unresolved as the relationship between reason and emotion/will is complex. Famously philosopher David Hume claimed that reason ‘is and should be the servant of the passions‘ (although for an account of exactly what he meant by this see Reason).

Moral psychology

Modern moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt in the book ‘The Tail That Wags the Dog‘ points out the dominant role of emotion in our behaviour and suggests five possibly innate psychological themes around which our moral norms appear to be organised. Franz Waal in The Bonobo and the Atheist (2013) argues that we do not develop morality from de novo through rational reflection ‘we received a huge push in the rear from our background as social animals’.

Our own experience of the power of emotion over reason (like a trail of broken New Year’s resolutions) demonstrate very clearly how our behaviour is influenced by factors other than reason. Reason tends to adddress long-term consequences, while emotions tend towards short-term satisfaction. However, the relative roles of reason and passion are in principle empirical questions and we need not give up finding some kind of solution to this controversy. We all like to think we have good reason for our moral choices. But many feel moral repugnance at, among others, – incest and homosexuality – when we cannot find sound reasons for doing so, referred to in moral psychology as moral dumbfounding. People say things like ‘it just seems wrong’.

One way that reason can influence our behaviour is through the acknowledgement that our moral choices can be strongly infuenced by the situations in which we place ourselves and by a full recognition of the various ways we are subject to cognitive bias.

Moral philosophy

For the moral philosopher perhaps this is all irrelevant. If ethics is indeed about rational decisions then there is no place for moral intuitions which cannot determine what is ‘right’ or ‘good’ or what ‘ought’ to be done. Ethical propositions are fundamentally different from those of psychology or science which concern themselves with ‘is’ statements.

Behavioural science focuses on the ‘inner’ factors influencing our moral behaviour, our moral intuitions and reason. At heart behavioural science is probing our human nature to find the source of moral behaviour. Moral psychologists like Haidt maintain that most of our moral behaviour is the result of gut feelings while moral philosophers like Sidgwick maintain, on the contrary, that morality is the use of reason to manage such feelings.

What are ‘the passions’

But, recalling the problem of nature vs nurture we can recognise that morality is likely to be a relationship between factors that are working from ‘inside’ us and factors that exist ‘outside’ us. From an evolutionary point of view ‘morality’ would encourage behaviour that promotes reproductive success. Biological goals of reproductive success and general flourishing are congruent with utilitarian goals of happiness and pleasure. Morality then appears to be an interaction between our (albeit obscure) human nature and our environment mediated to a greater or lesser extent, more or less successfully, by our reason: it is one of the ways we attempt to adapt to our ‘outside’ (environment, and in this case mostly other people) in a way that will maximise our flourishing/common good/happiness/pleasure or sustainability.

Reason without passion

De Lazari-Radek & Singer suggest that moral action may be initiated by what can be called normative reasons or motivating reasons. If indeed moral action is motivated primarily by will or passion then this becomes of little interest if we wish to distinguish a rational moral action from a passionate one. An example of a normative reason would be when I decide to visit the dentist every year in March for a check-up. This decision is made in an objective way irrespective of whether I like the idea, agree with it, or desire to act in accordance with it. In contrast, after making this decision if I subsequently have a bad toothache, I have a motivating reason to go to the dentist. [11] Universal rules like the categorical imperative are independent of the will.

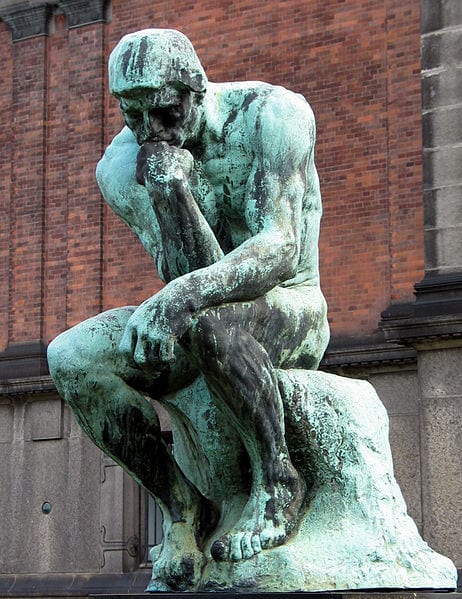

The Thinker – Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons