Classification

Classification of the Natural World

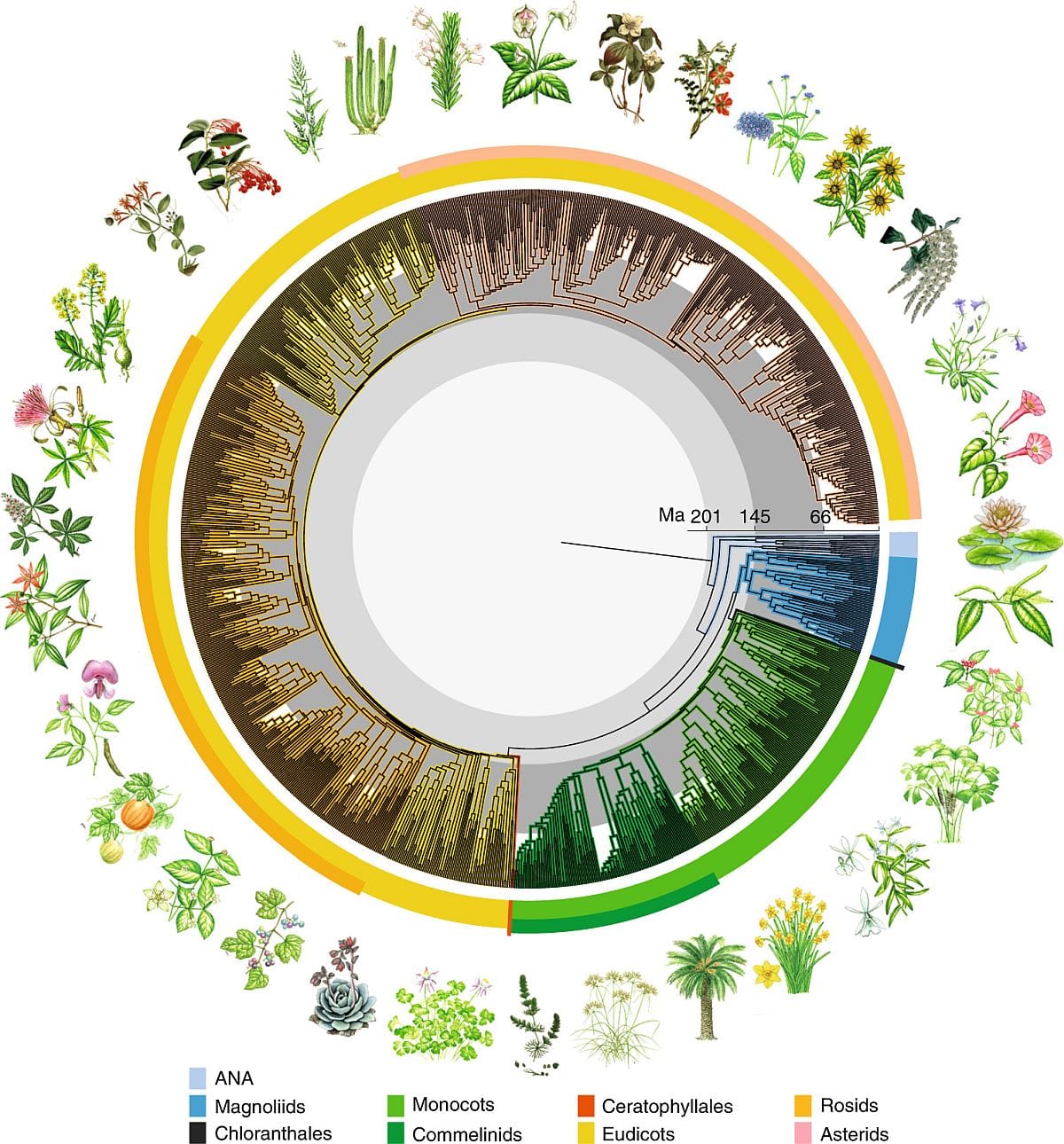

Linnaeus’s “Sexual System” of plants.

(10th edition of Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1758), p. 837)

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Hanno – botanica.org – Accessed 13 February 2021

There is classification as an act or process, and a classification as the representation that is the outcome of that process.

Although classification is generally associated with human mental processing, it is, in its most generalized sense, a form of adaptation of biological agents to the world – the discrimination and ranking of the objects of experience. Each organism adapts to its environment in its own way depending on the form of its sensory apparatus, its physical structure, and proximate goals – but all share the ultimate goals of survival, reproduction, and flourishing (biological axiom). Humans, like all organisms, are constantly classifying, but the classifications that we are most familiar with are products of cultural agency – the public collaborative and shared classifications that contribute to collective learning – like the various classification systems developed by science.

– Three inter-related articles address the problem of establishing a consensual systematization of our knowledge about the relationship between plants and people.

The investigation begins with a study of classification as a means of establishing the grounding principles for such a study. It then moves on to discuss plant classification in general, not just the formal scientific study of plant taxonomy. The final article, plant-people taxonomy, tackles directly the problem of establishing a new academic discipline, the study of plants and people. The article plants and people provides an introductory context.For a combined summary of the articles on classification, plant classification, and plant-people taxonomy see the Epilogue –

Introduction – Classification

When we think of classification we tend to think of the classification systems used by science. These are representations of the world that have been established in a public and collaborative process of collective learning. One obvious example is the classification of animals and plants that we learn in biology classes at school.

But, looked at in a more general and detached way, classification is a form of mental adjustment or orientation to our surroundings as we try to understand and explain our place in the world. Biological classification is a very general form of classification, but classification can be more specific, like a train timetable.

Classification can also be private and individual, even unconscious, as our minds sift and sort their subject matter. Think of the staggering automatic mental computation that must be going on as we orientate ourselves to the objects around us when driving.

Every classification is devised for a purpose so, in its broadest sense, classification is a form of adaptation to our environment. Expressed in this way it becomes an expression of biological agency and, as such, it can therefore be manifest in mindless, unconscious, conscious, and cultural forms (see life as agency), although it is the cultural forms that know best.

This article first examines classification in its shared and mindless form as orientation to the world before examining the usual minded aspect of classification as the ordering of experience and the kind of mental processing that must underpin both its unconscious and conscious forms.

An investigation of the principles of scientific classification then provides some insight into a method for formalizing the study of the relationship between plants and people.

Significance of agency

Classifications do not arise in an arbitrary way, they are there for a purpose: and where there is purpose there is agency.

Responding to the world in an agential way requires flexibility of behaviour – the capacity to adjust or adapt in relation to the environment. Classification, then, is one aspect of the guidance or ‘direction’ applied to behavioural flexibility, but this need not be minded direction. This orientation to the world (response to environmental stimuli) involves short-term (single-generation) behaviour that can lead to long-term (evolutionary) structural and genetic change.

The flexibility of behaviour we see in different species differs in both kind and degree.

The mode of environmental orientation (classification) is different for each organism and it determines the organism’s umwelt or ‘reality’ – its species-specific ‘sensing’ of what the world is like – what is important for its survival, reproduction, and flourishing . This will depend on the way in which an organism senses and interacts with the world. The umwelt of a crab is very different from the umwelt of a plant, though both share the same ultimate values of biological agency.

Most organisms adjust to their environments in an automatic, mechanical, and mindless way.

Mindless classification

For humans, the mindless adaptation of simple organisms to their environments seems a puny device when compared with the conscious decision-making that brings order and security to our lives.

But mindless biological agency is as crucial to humans as it is to any other organism. Human minds do not transcend mindless biological agency, they extend and build on it.

The autonomic nervous system (once known as the vegetative nervous system) is a control system that regulates life functions such as heart rate, digestion, respiratory rate, urination, and sexual arousal, not to mention reflex actions like coughing, sneezing, swallowing and vomiting. All of these mindless (though not nerveless) bodily functions so crucial to our existence are harnessed in the service of the universal values of the biological axiom.

The goal-directed (purposive) character of classifications provides a useful first principle of classification. Classification is a product of biological agency that may be mindful or mindless, but every classification has a purpose or reason. For humans, as for all organisms, there will be any number of proximate reasons for classifications as adaptive interaction with the environment, but the ultimate purposes will be survival, reproduction, and flourishing.

Principle – all classifications serve a purpose or reason because they are the products of biological agents that may be mindful or mindless (but whose ultimate purpose is survival, reproduction, and flourishing). Classification in its most general sense, is the means whereby organisms adapt to their inner and outer environments. In humans, classification may be an individual unconscious or conscious decision-making tool or a publicly constructed cultural tool, like a scientific classification

The generality of mindless adaptation to the environment seems a long way from the familiar classifications of cultural agency – the train timetables, charts of the scientific organization of the biological world, the periodic table of the elements etc. Before examining these products of cultural agency more closely, though, there are two aspects to classification that need closer attention.

First, the structure of classification systems in general and, second, the kind of mental processing that is required to produce them.

We can begin by looking at our human process of classification through the lens of the four kinds of biological agency, recalling that we have already considered the ignored but vital mindless agency of our autonomic nervous system.

Unconscious classification

Many of the miraculous ways we minded humans orientate ourselves to the world lie outside the mindless responses of the autonomic nervous system, or the conscious deliberation of our individual minds, or even the cultural and social norms that we understand and follow. There is another kind of agency, the unconscious agency that goes on behind the scenes.

How is it that we can drive safely? Clearly, we do not consciously assess every possibility as our surroundings rapidly change. And there is more than our autonomic nervous system brought into service as we unconsciously protect our wellbeing. This unconscious processing is a truly astounding aspect of our biology, not unlike the intuitive precision needed for an owl to catch a fleeing mouse. It is also very different from the considered process of writing down a shopping list.

Conscious classification

But what is the actual mental process of mental sifting and sorting that must be going on as we order and reorder representational units in the flow of classification (world ordering) that follows the constant shift in our focus of attention? How do we prioritize our actions as we assess all the implications of what we are doing when driving through a busy shopping centre?

Our minds are forever ordering and reordering our experience. Groups of mental objects, their properties and relations are united with others to become more inclusive groups, properties and relations. The objects in one classification become the properties in another and so on and so forth in a system of mental classifications that are constantly changing to accommodate our changing circumstances, focus, and therefore purposes.

Cultural classification

But classification can also be part of a public collaborative and progressive system of representation that contributes to collective learning – as when we construct the various classification systems used by science. This is how we think of classification in a strict sense.

Notable here is the scientific classification of physical objects: the biological organization of organisms into a system of hierarchically ranked and formally named groups or categories, and the arrangement of elements into the Periodic Table. This is what we refer to as classification in a more restrictive sense.

The latter are sometimes referred to as special-purpose classifications and they often require expert development using the latest technology that pushes our collective learning methodology to its limits.

In sum: we tend to think of classification as an intentional and conscious process. We forget that we share with other organisms the capacity for unconscious classification. Indeed, most of our classification, most of the time, is an unconscious and private matter – a myriad of automatic mental computations as we instinctively orientate ourselves to the objects around us.

This unconscious aspect of classification is something we share with many other biological agents along with the kinds of processes we associate with the autonomic nervous system.

Principle – formal scientific classifications are public and progressive representations of the world that contribute to collective learning.

Classification of classifications

To establish the principles of classification we need to understand, not particular classifications, but classification, as a whole. We need to establish a classification of classifications, an in-principle account of the way that all classifications are constructed – a metataxonomy.[23]

As a thought experiment it is informative to consider creating a classification of everything that there is. But where would we start? Of what does the world consist? Does it consist of one thing or many? Is it physical objects, or ideas? Is it just fermions and bosons. Or is it, perhaps, reducible to number, or information? This metaphysical question has no answer that can be subjected to empirical investigation. When we ask this question we do not confront the universe, we confront ourselves, our agency, and our cognitive limitations.

The selection of objects for any classification depends on our agential thinking. It depends on the purpose of the classification.[15]

When we cannot resort to evidence, we fall back on our intuitions (our non-empirical assumptions) . . . and when science is asked (metaphysical) questions that cannot be answered with certainty, it too falls back on intuitions[20] telling us that the world consists of objects, properties, and their relations. Whether this is the way the world ‘is’ can be debated, but this is the way our minds perceive it.

As a first step (and regardless of the nature of the external world) we can acknowledge the existence of units of mental representation as the objects of mental processing. Without these representational units the world could not make sense.

Aristotle gave us a tentative foothold in the mystery and multitude of existence by telling us that the world can be reduced to three kinds of representational unit: objects (everything from abstract concepts to physical objects in the world), their properties, and relations.[21] This may seem a predictably obscure and contentious statement from a philosopher but, since we have to start somewhere, this is a point of departure that, as we shall see, demonstrates a remarkable insight into the way we intuitively organize our thoughts. It is an effective and generalized way of coming to terms with everything.

The significance of Aristotle‘s observation is that it neatly and succinctly captures a universal character of all classifications, both formal and informal . . . our intuitive way of experiencing and interpreting – our way of classifying – the world.[24]

In any event, his schema is a useful heuristic for analyzing the nature of the world and our classification of it: to understand and provide an explanation for any object requires knowledge of its properties and relations.

We can now build an in-principle terminology for the critical elements of all classifications, based on the role that they play.

Objects – the things to be classified (operational units, taxonomic units, taxa) – e.g. for plants: families, species, individuals etc. The groups into which objects are classified can then become the objects of further classification.

Properties – the grouping or selection criteria (characteristics) that define or circumscribe groupings – e.g. for plants, the characters. Grouping may be based on one (monothetic) or many (polythetic) characters.

Relations – the arrangement of groups in relation to one another – for plants, the classification system

Since classifications are directed towards ends (they arise for a reason or purpose) they necessarily entail some kind prioritization, ranking, valuing, or preference.

This is a highly flexible and abstract schema whose contents, in actual cases will, as we have seen, depend on the purpose of the classification. Objects that are closely related in one system may be distantly related in another. Also, because of its generality, the objects in one classification system may be properties or groups in another, and so on.

Principle – classification begins with our intuitive recognition of objects, their properties, and relations

Principle – terminology of metataxonomy – objects are classified into groups based on possession of properties. Groups may be further arranged into classification systems. Classification is a function of the teleology of agency: being purposive there is ranking and prioritization evident in the selection of objects, grouping characters and the criteria used to differentiate groups into a more general classification system.

Principle – the goal of classifying a representational unit is to place it into an already existing group or to create a new group for it, based on similarities and differences to other representational units. This may require the formation of a hierarchy of categories

Mental processing

It is now time to look at the more familiar side of classification – the ordering of experience in our minds.

We take it for granted that our minds convert a buzzing confusion of sensory and other information into an experience that is meaningful, coherent, and ordered. But how can we begin to explain how this ordered categorization – this minded classification of everything – is achieved?

One approach to this problem is through neuroscience, by studying the anatomy and physiology of our nerve cells and brain, along with all its electrical circuitry, the firing of neurons and so on. We might also get assistance from the multitude of scientific disciplines that are now investigating the operation of our brains from many other perspectives.

Another approach is to resolve as much as possible in principle – by considering the preconditions that make such an outcome possible.

Principle – the goal of classifying a representational unit is to place it into an already existing group or to create a new group for it, based on similarities and differences to other representational units. This may require the formation of a hierarchy of categories

Mental predispositions

But how do our minds go about sifting and sorting their contents into something meaningful that can guide our decisions in a purposeful way?

Eighteenth century German philosopher Immanuel Kant argued convincingly (against the views of many of his esteemed contemporaries, notably Englishman John Locke) that the mind was not a passive ‘blank slate’ on which a person’s experiences are written. Rather, the mind contributes to ‘knowledge’ by actively structuring our experience. Kant even outlined in detail how he considered our minds contribute to our understanding of the world.

Kant suggested what he called a Copernican Revolution in the way we should understand the world. This was an alternative to the 18th century ‘spectator’ interpretation of the world. In the 18th century it was assumed that science described the world in a totally objective way – as it is in ‘reality’. Instead, Kant proposed that it is our minds that situate all our experience within the context of space and time (his transcendental aesthetic) and within logical structuring principles or ‘categories’ (his transcendental analytic).

The detail of Kant’s argument remains contentious, but his general claim that the mind frames our experience and knowledge is now widely accepted. To use Kant’s form of expression: the mind must have certain predispositions if we are to have any meaningful experience at all.

Since Kant, the whole field of psychology has opened up. It is now clear that our minds are constrained by our species-specific human biology in many ways. So, for example, we do not experience everything it is possible to experience, all at once. The flood of incoming sensory information is subjected to our mental processing which, by abstraction, reduces and organizes our immediate experience. This is an essential precondition for us to operate effectively in the world.

The consequence of this mental processing is that we exist in a world that is unified, coherent, and meaningful . . . not a confusing maelstrom of competing sensations.

So, is it possible to know, in principle, how the intuitive elements of our classifications are processed in our minds?

Four predispositions

Is it possible to outline, in more detail, the way that we humans convert the multitude of ideas in our minds into a coherent experience that allows us to live effective lives? This might appear a tall order but, like Kant, we can examine the necessary preconditions of mental processing that make meaningful experience possible.

There are, in principle, at least four mental predispositions necessary for meaningful experience.

First, the mind segregates the world into meaningful units of representation that are the elements of mental processing (concepts, percepts, abstract ideas, representations of objects in the world, whatever). The way our minds convert the field of colours, textures, and tones that falls on our retinas into meaningful and discrete objects like cars, people, trees etc. is a miraculous mental accomplishment that we all take for granted.

Second, it focuses on a limited range of these objects at any given time (depending on the demands of the moment) with the result that our attention is divided into a foreground and background. Third, it groups these categories in numerous ways (depending on the demands of the moment). Fourth, it ranks its categories and category groups in relation to one another (according to the demands of the moment) in a way that can guide action.

Though this is clearly a grossly simplified characterization of what goes on in our brains, and it is possible to devise other formulations, it nevertheless expresses what in principle must occur for us to operate effectively in the world.

These four processes of segregation, focus, grouping, and ranking, it would seem, occur in all cultures and are, indeed, necessary for our survival. They are also part of the mental ordering of our experience that we associate not only with classification, but reason, evaluation, and much more. They are an evolved and inherited minded biological characteristic that is part of our human nature.

The way our brains structure experience determines our species-specific ‘reality’, our experience of what the world is like. As an ordering process it is also a key ingredient of our uniquely human capacity for reasoning.

These processes seem to occur simultaneously and with varying degrees of consciousness. At one extreme might be the way our eyes move intuitively towards the source of a noise, while the smooth integration of conscious and unconscious decision-making when I am driving is a much more miraculous and complex fusion of the conscious and intuitive processes of orientation. The solving of a mathematical problem is a fully conscious process.

(a) segregation – divides the world of experience into representational units amenable to mental processing

(b) focus – confines attention to a limited number of categories, dividing attention into a foreground and background

(c) grouping – arranges units into groups using selection criteria that are meaningful in relation to desired objectives (the structure of groupings in particular cases is called the classification system)

(d) ranking (prioritization) – arranges groups into a ranked order – which facilitates decision-making and action

Principle – we structure existence in terms of the three elements – objects, their properties, and relations – which we then process by means of mental segregation, focus, grouping, and ranking

Each of these processes is now considered in more detail as they relate to the construction of scientific classifications.

Structure

Though the basic constituents of classifications are few, their final arrangement into a formal classification system can be achieved in many ways. There is a substantial difference between the structural arrangement of objects in a shopping list and a chart representing the organization of plants and animals into groupings that constitute the tree of life.

We now have the basic tools needed to perform a classification. We need a clear statement of purpose; a list of objects to be classified; and a set of purpose-dependent properties (selection criteria) with which to group the objects.

But where there are multiple groups that make up a classification system then we must also consider the way that these groups are arranged in relation to one another, and this needs further discussion.

Scientific classification

Scientific classifications are popular because they contribute to general knowledge and the increased predictivity that helps us manage our individual and social lives.

By ‘scientific classification’ is meant – the best possible arrangement (representation) of objects that satisfy its purpose – remembering that scientific classifications describe the structure of the universe in a way that is always open to further investigation, and endless refinement.

How can we maximize the scientific quality of the principles that we use to construct public classifications?

Clear & distinct ideas

Any individuation of ideas indicates some degree of discontinuity in our minds – but this can be a matter of degree – a complication that becomes apparent when we try to convert ideas into words.

Consider the meanings of the following: ‘my cup’, ‘the FA cup’, ‘cup’, and ‘crockery’. Names, as representations, relate to the world in complex and confusing ways and with varying degrees of abstraction.

It helps to think of word meanings as being part of a web of knowledge with connections between meanings being of different strength. Meanings of words can merge with other meanings like streams of different strengths flowing into one-another.

In the interests of scientific precision, it is useful to be aware of two kinds of category or idea – the classical and fuzzy.

Classical categories

Philosophers seek clarity in communication by using categories that are clear and distinct. Plato spoke of ‘carving nature at the joints’, by which he meant dividing the physical world into units that we believe exist in nature not just as representations in our minds.

Aristotle described ‘classical’ categories with defining features (properties, selection criteria) that were both necessary and sufficient. These defining features became known as ‘essences’ and the use of classical categories called ‘essentialism’. The value of these categories was that they were clearly defined, mutually exclusive, and collectively exhaustive.

One obvious scientific example of classical categories, as established by careful research, is the Periodic Table of elements, each element defined by its atomic number. Though gold has many properties that can be used in its definition (e.g. colour, malleability, melting point etc.), its definition as the element with atomic number 79 is both necessary and sufficient, simple and precise. Before the advent of atomic theory other properties were used to define gold but atomic theory refined these older (fuzzy) definitions. Unfortunately, this degree of clarity occurs more frequently in logic and mathematics than in nature. But Aristotle reminds us of the power of simple and distinct ideas.

The Darwinian theory of natural selection and gradation of nature reminds us that the search for essences in nature is a vain hope, but this does not mean that diagnoses (definitions) cannot be made more precise. The scientific diagnosis of a species aspires to the ideal of the classical category, but evolution by descent with modification (rather than special creation of individual species) has made the provision of ‘essential’ diagnoses of a species (as classical categories) a tall order.

Fuzzy categories

We now know that most words have blurry meanings that grade into the meanings of other words in the web of knowledge.

As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein pointed out, the notion of a ‘game’ is not a classical category. The many different activities that we call ‘games’ show a ‘family resemblance’ rather than a set of necessary and sufficient (essential) conditions. In other words, what we mean by ‘game’ grades into the meanings of other categories making it a fuzzy, rather than clear and distinct, category.

Awareness of the wide application of fuzzy categories in our communication has given rise to new conceptual clustering tools like those developed in fuzzy mathematics (fuzzy logic and fuzzy set theory which developed in the 1960s) in which objects may belong to one or more groups but to varying degrees. Psychologists studying ‘category learning’ investigate the possible ways our brains compare categories and establish group membership.

For the scientist, the point is to maximize the clarity of the categories under investigation.

Metaphor

In both everyday and scientific discourse, we simplify the complexity and abstraction of existence by using metaphor as a means of conveying similarity. This can throw a beam of light on our understanding but also mislead when taken literally. We must always be on the lookout for its presence.

Principle – the units of classification will maximize the use of classical categories while minimizing the use of fuzzy categories and metaphor

Relata & prediction

Representational units,[11] as relata, may take any form that is available to our minds – from abstract to concrete, simple to complex, general to particular, more inclusive to less inclusive etc. We refer to them in many ways – as concepts, percepts, physical objects, taxa, and so on.

In a classification the relata are the taxa or operational units (OUs) that are being classified. And, when considering classification in a general sense, relata may of course be mindless or unconscious, with the conscious relata of formal public classification systems being a small subset of this totality.

Historically, science has been most concerned with ‘natural kinds’ as individuated physical objects in the world rather than subjective constructs. These are categories that have been exhaustively tested by experiment, observation, and reason.

Two examples stand out. First, the Periodic Table whose objects are the elements whose grouping by chemical properties[22] relates to their atomic mass. Second, Biological Classification whose objects are organisms grouped according to the inheritance of characteristics derived from ancestors by descent with modification.

Scientific classifications are regarded as effective and efficient when they provide strong predictivity, though this will always be in relation to the conditions established by the purpose of the classification.

Predictivity of the behaviour of physical objects is increased in proportion to their physical relatedness (as natural groups), and our scientific understanding of that relatedness.

Unlike, say, the group ‘all the objects on my shopping list’ the list of chemicals in the Periodic Table have intrinsic physical connection.

Similarities between organisms have long been recognized, but only post-Darwin has this likeness been acknowledged as physical continuity, with modern genetic analysis vastly improving our capacity for their discrimination.

Focus

Life confronts us with a buzzing confusion of sensations and ideas. We have managed to talk to one-another about these ideas using some 50,000 words. Efficient communication demands that we minimize the verbal categories we use to explain them as, like a librarian, we organize the titles on the shelves of our knowledge according to purpose.

So, for example, every academic discipline attempts to maximize its efficiency by systematizing its knowledge. In computer science and information science its representation of objects, properties, and relations is expressed as a relationship between concepts, data, and entities in an ‘ontology’.

So, the mind not only fragments experience into meaningful categories, it also focuses our attention on a restricted range of these categories so that, at any given time, our attention consists of a foreground – the focus of attention – and a background of available categories of which we are not immediately aware (intuitively ignored).

So, when we learn about the world at school we do so by concentrating on small portions of our overall human knowledge, say, History, English, Music, and Chemistry.

Focusing restricts the mind to a manageable number of categories at any given time. So, for example, plant classification restricts our attention to plants and the properties of plants that are used as grouping criteria.

Principle – the choice of representational units that comprise the relata and selection criteria of a classification depends critically on the purpose of the classification

Grouping

Grouping[19] refers to the process of group formation as determined by the selection criteria. This can be distinguished from the structure of the groups formed in this way (which demonstrates the relationship between the groups so-formed) which is the classification system. The choice of selection criteria is determined by the purpose of the classification.

Selection criteria

It is selection criteria that are used to discriminate or define the groups within the classification.

The best classifications are those that serve their purpose in the most efficient way. To maximize the efficiency of a classification we refine, as far as possible, the selection criteria that filter the objects being classified. Careful choice of selection criteria reduces the number of possible outcomes and increases the precision of the result.

Selection criterion may be simple – say, ‘being yellow-coloured’, but sometimes more complicated and amenable to improvement, as when the element ‘gold’ is selected using its atomic number rather than the properties of being, for example, a yellow, malleable, and expensive luxury good.

As with all representational units the scientific aspiration is to classical categories and natural groups.

A distinction may also be made between: an arbitrary (artificial) group e.g. plants with yellow flowers, and a natural group e.g. plants with one cotyledon; groups of special human interest e.g. medicinal plants or minimum human interest e.g. plants with double stomata; and groups based on extrinsic factors e.g. plants from China, or intrinsic factors e.g. plants with two cotyledons; properties that are classical or fuzzy (continuous e.g. leaf length or discontinuous e.g. fruit type).

The scientific aspiration is for properties that are natural, discontinuous, intrinsic.

Principle – the goals to seek in the choice of selection criteria include properties that are intrinsic, discontinuous, and will form natural groups

Classification systems

Objects may be divided into many groups which can themselves become united into more inclusive groups or further divided into less inclusive groups in a process that potentially continues indefinitely. New groups become new objects, each circumscribed by their own novel properties and forming new relationships to other groups. It is the representation of group relationships that constitutes the classification system and we have learned, mostly from scientists and librarians about the structures, of varying complexity, that classification systems can assume. This is a little-known aspect of our knowledge accumulation and organization.

A simple alphabetical list is a classification based on one property (order of letters in the alphabet). In contrast, living organisms are scientifically classified using properties (characters) in such large numbers that powerful computers are required to produce the groupings.

The goal of these classifications, like that of all science, is to maximize representational power so it is important to be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of different classification structures.

Hierarchies

Most formal classification systems are organized into some form of hierarchy. That is, the groups formed are ranked or prioritized in some way in relation to one another. For example, drawn on a sheet of paper, or in 3-D, those groups sharing the most properties may be placed closer to one another.

Many classification systems have the groups arranged in metaphorical levels or ranks, like the rungs of a ladder, so that there is a ‘top’ and a ‘bottom’. This powerful intuitive metaphor was once assumed to reflect the God-given structure of human society, and is still used in science to represent the organization of the physical world. It also reflects the intuitive way that languages are constructed (see later).

The scientific precision and information content of hierarchies depends on the structure of the hierarchy that is employed.

Nested hierarchies

In a strict nested hierarchy the groups are contained within other groups – like a Russian doll which contains another doll inside, and another doll inside that one, and so on.

A scientific example would be the Linnaean biological classification of organisms into orders, which contain families, which contain genera, which contain species . . . etc. Knowing that a plant has the species name Lactuca sativa (Lettuce), connects us to a vast store of associated historical and biological information. An example of how this kind of plant classification works at high levels would be the single category ‘seed plants’ which is then divided into the groups ‘flower-bearing plants’ and ‘cone-bearing plants’. The flower-bearing plants can then be divided into those which have one seed leaf (monocotyledons) and those which have two seed leaves (dicotyledons) . . . and so on down the hierarchy of ranks.

Strict nested hierarchies like this exhibit several important properties:

Inclusivity – they are progressively more inclusive as ranks go from bottom to top

Exclusivity – an item in a strict hierarchy can only belong to one group at a particular level or rank.

Transitivity – the properties that define the objects at higher ranks are passed on to the lower ranks

Clear boundaries – the properties defining group membership at a particular rank must be both necessary and sufficient (a classical category)

An example of transitivity would be that all vertebrate animals (Vertebrata) have a vertebral column no matter how they are subsequently subdivided. Sub-groups, though resembling one-another by sharing the properties of ‘higher’ more inclusive groups, nevertheless differ in the properties that uniquely define them.

A name, as a binomial, can be used as a device to express both similarity and difference. So, Homo sapiens as a species shares the property of being human (expressed in the genus name Homo), but it differs from other species of human by being uniquely H. sapiens, the ‘wise human’. There is thus a clever association and distinction – the binomial (a name consisting of two words) expressing both similarity and difference at the same time.

An example of exclusivity would be that Homo sapiens cannot be, at the same time, Homo heidelbergensis.

Strict nested hierarchies require clarity about similarities and differences between groups. Hierarchical definitions express both affinity and distinction (similarity and difference) in an economical way.

Transitivity allows the hierarchical structure to accumulate information that is useful for prediction: inclusivity (the containment of groups within groups) demonstrates the evolutionary principle of descent with modification.

The formal structure of nested hierarchies works well for items that can be clearly defined, because they have unambiguous group boundaries. However, in daily life we use many (fuzzy) categories with indistinct boundaries so the demand for mutual exclusivity cannot be satisfactorily met.[6] In such cases the members of groups at a particular rank share a family resemblance rather than fulfilling strict necessary and sufficient conditions – and some items at a particular rank may share closer resemblance than others.

In addition, limited knowledge can diminish the power and reliability of definitions and grouping items using more than one criterion can become unwieldy (say classifying plants based on both flower structure and fruit structure).

The effectiveness of a hierarchy in achieving its purpose will only be as good as the knowledge used in its construction and lack of clarity about items and their definition diminishes the power of transitivity.

Difficulties in creating clear categories in science are well known, for example, in the classification of rapidly-changing viruses or in defining the nature of particular smells. Descent with modification can itself lead to graded transitions rather than necessary and sufficient groupings (essentialism) as we try to impose logical order on graded nature.

Modern plant classification (cladistics, phylogenetics, and molecular systematics) is based on presumed evolutionary relationships, not an arbitrary assignment to ranks; it recognizes species but does not use the terms genus, family, order, class, phylum or kingdom. Thus, cladistics has no ranks – but it does have a hierarchy which arises from the fact that some organisms share a more recent common ancestor than others as a consequence of descent with modification. A taxon that includes an ancestor and all of its descendants is called a clade.

Principle – strict nested hierarchies exhibit: inclusivity – they are progressively more inclusive as ranks go from bottom to top; exclusivity – an item in a strict hierarchy can only belong to one group at a particular level or rank; transitivity – the properties that define the objects at higher ranks are passed on to the lower ranks; clear boundaries – the properties defining group membership at a particular rank must be both necessary and sufficient (a classical category)

Trees

Another kind of hierarchy is exemplified by military rank. This hierarchy has clear distinctions between groups (like private, sergeant and lieutenant) but there is minimal transitivity between the groups so, for example, the characteristics shared by a private and a sergeant are somewhat obscure.

Further, trees lack inclusivity: though a species is a member of a genus which is a member of a family – a private is not a subdivision or kind of Sergeant who is, in turn, a kind of Lieutenant. A tree indicates a chain of command but does not include a clear definition of the nature of the authority.

Tree – a nested hierarchy of Army Officers.

Trees lack inclusivity

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Totobaggins – Accessed 5 January 2021

Principle – trees strict nested hierarchies exhibit: inclusivity – they are progressively more inclusive as ranks go from bottom to top; exclusivity – an item in a strict hierarchy can only belong to one group at a particular level or rank; transitivity – the properties that define the objects at higher ranks are passed on to the lower ranks; clear boundaries – the properties defining group membership at a particular rank must be both necessary and sufficient (a classical category)

Partitive hierarchies

A further kind of hierarchy is the partitive hierarchy with the part relating to a greater whole in some way. A partitive hierarchy might arise, for example, when we subdivide a geographic region. Melbourne is a part of the state of Victoria, which is a part of Australia. This is an inclusive hierarchy (though Victoria is not a kind of Australia it is a part of it) where certain properties are shared.

Partitive hierarchies share, with nested hierarchies, the characteristic of passing from the general (the most inclusive domain) to progressively smaller or less inclusive parts. But note that a simple confusion can arise here. Objects that share the characteristic of just being a part of something can be quite different in general character: an apple core, a train ticket and bottle may all be parts of the waste bin while, in a nested hierarchy of animals we know that those animals that are vertebrates will share certain similarities. Objects that appear on my weekend shopping list might have almost no connection.

Trees require a knowledge of the characteristics of the items being classified. The structure of the tree will be determined by the nature of the relationship between the parts: is it part-whole; cause-effect; process-product; start-end etc.

Trees organize categories in a way that defines how they are related and/or the degree to which they are related (spatially, metaphorically), and/or the relative frequency of items within a particular category. However, a tree is constrained by the order in which distinctions are drawn and this may require subsequent modification.

In a hierarchy the information flows (metaphorically) not only ‘upwards’ and ‘downwards’ between levels, but ‘laterally’ between items at the same level.

In trees the ‘lateral’ categories might contain very different objects so they tend to be strong along only one dimension of interest and are not so effective at representing multidirectional complex relationships. As with hierarchies the choice of key defining characteristics can be a matter of dispute and trees allow only partial inference.

Ranking

Though we assume that the representational units of our human existence – trees, people, cars, books etc. – exist in the world, our focus on these objects rather than others is determined by our biology, our umwelt (those factors important for our survival, reproduction, and flourishing). Thus classification is never totally objective, although it may be minimally based on similarities and differences – as when we classify elements and animals as natural kinds.

We are intentional animals and so the categories in the foreground of our attention, our focus, are the objects we value. That is, they are (or need to be) ranked, prioritized, or specially selected in some way depending on our needs, desires, purposes, and reasons – as when I am shopping for strawberries and a cauliflower.

The prioritizing of objects relative to one-another I call ranking. The ranking of the objects of our experience is what makes our (and other animals’) behaviour both purposive and meaningful: part of our classificatory adaptation to circumstance.

Principle – ranking of groups is based on the purpose of the classification which ultimately depends on those factors important for our survival, reproduction, and flourishing

Selection criteria

Properties, as selection criteria for groups, may be weighted (emphasized or given precedence) according to their utility.

A useful distinction may be made between properties intrinsic to the object and those that are extrinsic. Though weighting may be arbitrary or imprecise, if properties are used without weighting problems arise too. A classification based on unweighted characters is called a phenetic one (based on appearances) as opposed to a phyletic one (based on evolutionary change within a single line of descent), in which characters are weighted by their presumed importance in indicating lines of descent.

Grouping

Grouping is based on similarity and difference. As a general principle groups based on as many properties as possible are best, especially properties that are easily observed and described.

Groups are most effective when they are discrete (defined by necessary and sufficient conditions) but division into sharply separated groups is generally not possible.

Once groups are established they are often assigned ranks as degrees of importance, status, or priority.

Choosing ranking criteria

Classifications may themselves contribute to knowledge generation. This occurred, for example, with the prediction of new and, as yet, undiscovered elements and their properties following the construction of the Periodic Table. Science was also facilitated by classifications resulting from new scientific technology, as with: carbon dating, DNA analysis, remote sensing, radio-astronomy, the crystalline structure of gems (rather than their hardness) and so on. Understanding the chemical structure of biological compounds helps establish what unknown compounds are possible but as yet undiscovered, or which may be synthesized in the laboratory . . . and so on.

The point here is that for science to proceed it must have some framework of ideas concerning the nature of ‘everything’ from which to launch its investigations. But, as explained, we have no such foundation. So, what do we do?

The point, if it needs to be made, is this. Although we humans are extraordinarily sophisticated in our explanation, understanding, and manipulation of matter, there will always be a residue of species-specific interpretation. It is we who provide the selection criteria for all classifications.[16]The philosophical problem of category choice for our categorizations-classification dissolves when we realize that they are decision-making tools. They impose order by organizing categories into groups using selection criteria that achieve an objective, purpose, or use.

Language

We do not, cognitive scientists now believe, think in words, but in what has been termed mentalese.[9] Whatever the nature of mentalese, we communicate our experience using language that conveys our ideas by means of representational units, like a digital computer, even though the meanings of these units of communication often merge into one-another, as they might in an analogue computer.)

To share the categories (concepts) we form in our minds, we must communicate using spoken, written, printed, or electronic language. In this way we can refine our shared categorization which then becomes part of our potentially progressive collective learning.

Language & representation

Language provides us with a symbolic representation of the world. Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker gives an insightful example of the relationship between science and language in his book ‘The Stuff of Thought’ (2008) which shows how we embed, in a metaphorical way, the key scientific concepts of space, time, matter, and causality in everyday language. Nouns express matter as stuff and things extended along one or more dimensions. Verbs express causality as agents acting on something. Verb tenses express time as activities and events along a single dimension. Prepositions express space as places and objects in spatial relationships (on, under, to, from etc.). This language of intuitive physics may not agree with the findings of modern physics but, like all metaphor, it helps us to reason, quantify experience, and create a causal framework for events in a way that allows us to assign responsibility. He remarks . . . ‘language is a toolbox that conveniently and immediately transfers life’s most obscure, abstract, and profound mysteries into a world that is factual, knowable, and willable.’

We are inclined to think of the scientific description of the world as ‘reality’ – the fixed and final way the world actually is. But science is constantly testing these beliefs. We must always remember that factual statements, even those of science, are statements of strongly corroborated evidence, not the way the world is . . . even though, in practical terms, they provide us with extremely useful explanations.

The concepts and categories that make up our language are linked into a web of interconnected knowledge. It is the task of science to organize this knowledge as the best-for-purpose that we can possibly produce.[14]

So, how are inner experiences transformed into a language that can convey information from one head to another?

Cognitive scientists and linguists have discovered that we do not think in words, we think in ‘mentalese‘.[9] To share our cogitations with others we must translate mentalese into a spoken and written language.

The way we structure language provides us with an insight into the mental process of classification itself because it entails the organization/classification of words.

Web, string, tree

We may think of the way we structure language using a metaphor proposed by cognitive scientist and linguist Steven Pinker who refers to it as ‘the web, the string, and the tree’.

This too is a miraculous process that we all take for granted. Consider the librarian’s dilemma of cataloguing the web of human knowledge into a hierarchy of linearly-related topics knowing that so many topics cut across one-another. This is akin to the way classifications can cut across one-another depending on their purpose.

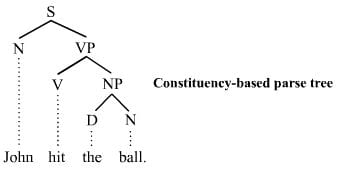

We have in our minds a web of interrelated categories. We organize these categories into a linear sequence (spoken or written) – a string – according to the rules of syntax which, together with the rules of word formation comprise its grammar. Grammar is our (species-specific) solution to getting complicated thoughts from one head to another. Words are arranged into phrases that are nested within sentences in the form of an inverted hierarchical tree.

‘Syntax then is an app that uses a tree of phrases to translate a web of thoughts into a string of words.’ The listener then works backwards, fitting them into a tree and recovering the links between the associated concepts.’

The hierarchy

So, we structure language like a nested hierarchy that is constructed in a boxes-within-boxes way with sentences containing substructures (phrases) that form an inverted tree when presented pictorially on the page.

Parse Tree as a Nested Hierarchy

S for sentence, the top-level structure in this example

NP – noun phrase. The first (leftmost) NP, a single noun “John”, is the subject of the sentence. The second one is the object of the sentence.

VP – verb phrase, which serves as the predicate

V – verb. In this case, it’s a transitive verb hit.

D – determiner, in this instance the definite article “the”

N – noun

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Tjo3ya – Accessed 3 January 2021

Commentary

Knowledge grows cumulatively and to make an advance in any field of study a student must add to the fine detail of their own discipline by doing classification as part of their original research . . . by either refining the categories already used by their discipline, or by adding new ones.

Classification, in its most general sense, is an interaction between an organism and its environment – the cognitive (broad sense) activity of adaptation – the process of discrimination and adjustment that guides flexible goal-directed behaviour. It is an ‘assessment’ of the relationships that exist between an organism and the objects on which its existence depends (its umwelt).

Human classifications have their origins in the pre-conscious structuring of the objects of our experience (categories) that we, both intuitively and deliberately, arrange in different ways to some end or purpose. This is the way that we intuitively relate to the world: it is the precursor to public classifications like those of science which are the result of a formal social process of collaborative refinement that contribute to collective learning as the growth of knowledge.

During the human process of classification, categories are subjected to a mental filtering using selection criteria that serve purpose of the classification. Four necessary and interrelated aspects of this innate mental processing can be usefully distinguished: categorization, focus, grouping, and ranking.

Collectively these processes help establish our human umwelt,[1] what is important in our lives – the way we experience the world – our sense of reality. As a way of ordering our experience classification is a poorly comprehended aspect of our faculty of reason.

Phylogenetic phenomena display the unusual characteristic of modification from a common origin are a major opportunity to apply special principles of classification. The evolution of organisms and language are examples of the way phylogenetic (tree) analysis that can give us valuable insights into the past and can be extended to other cultural phylogenies to take full account of vertical transmission, horizontal diffusion, and local socio-ecological drivers.[18]

The article on plant classification considers the possibility of a scientific classification of plants, not in relation to other plants, but in relation to humans – a topic of greater significance for the future of humanity.

Key points

- Our minds are constantly – both consciously and unconsciously – selecting, ordering, and arranging the objects of our experience

- The foundations of classification are laid with the pre-conscious structuring of experience that occurs before conscious deliberation

- Our intuitive ordering of the world is part of the way we represent the world, and it is the source of some of our metaphysical intuitions about the world. It is therefore part of our human nature and human reality, our uniquely human collective mental umwelt.

- Included in the pre-conscious mental processing there is: segregation, focus, categorization, and ranking. These aspects of our mental processing are hard-wired into our biological make-up; without them we could not survive

- For simplicity we can call all communicable units of experience categories, and it is these categories that can be variously grouped and prioritized according to selection criteria.

- The grouping of units of our experience towards some end or goal may be called categorization, and when categorization becomes a serious conscious and deliberate endeavour, as it does in science, we call it ‘classification’.

- Classification is the ordering or grouping of objects by criteria selected to achieve an end or goal.

- Taxonomy is the study of classification, its principles, and procedures.

- We communicate with one-another using language which provides us with a symbolic representation of the world. The categories that make up our language are linked into a web of interconnected knowledge.

- One of the tasks of science is to ensure that the categories we use to describe and organize our collective learning are the best possible. This is a task for science.

- Classifications are decision-making tools. There are an infinite number of ways of classifying categories but the categories chosen will depend on the purpose of the classification.

- Biological classification of organisms arranges them by their presumed evolutionary relationships

- One method of scientific advancement is the designation of an are of study (an academic discipline) with a community of scientists that constantly refine the categories, principles and procedures used by that study

- Plant classification is the arrangement of plants into groups according to selection criteria that serve a particular purpose. However, in common usage, the expression ‘plant classification’ refers to the organization of plants into groups that reflect their evolutionary relationships as plant taxa which, prior to Darwin and the theory of evolution, involved the organization of mostly morphological characters as similarities and differences.

- We study plants through the broad range of scientific disciplines that fall under the heading of plant science (formerly the narrower discipline of botany). There is no current and widely accepted system of categories, principles and procedures for the study of the topic ‘plants and people’

- ‘Categorization’ is a general-purpose term. When categorization becomes a more serious and shared social activity we call it ‘classification’

- Classification is the ordering or grouping of objects by criteria that satisfy an end or goal.

- Taxonomy is the study of classification, its principles, and procedures.

- Classification begins with the pre-conscious structuring of experience that occurs before conscious deliberation. This intuitive ordering of the world is part of the way we represent the world, and it is the source of some of our metaphysical intuitions about the world. It is therefore part of our human nature and human reality, our uniquely human collective mental umwelt.

- Included in the pre-conscious mental processing that is part of our human nature are: segregation, focus, classification, and ranking. These aspects of our mental processing are hard-wired into our biological make-up; without them we could not survive

- For simplicity we can call all communicable units of experience categories, and it is these categories that can be variously grouped and prioritized according to selection criteria.

- We communicate with one-another using language. Language provides us with a symbolic representation of the world. The categories that make up our language are linked into a web of interconnected knowledge. We need to ensure that the categories we use to organize this knowledge are the best possible. This is a task for science.

- Classifications are decision-making tools. There are an infinite number of ways of classifying categories but the categories chosen will depend on the purpose of the classification.

- Biological classification of organisms arranges them by their presumed evolutionary relationships

- One method of scientific advancement is the designation of an are of study (an academic discipline) with a community of scientists that constantly refine the categories, principles and procedures used by that study

- Plant classification is the arrangement of plants into groups according to selection criteria that serve a particular purpose. However, in common usage, the expression ‘plant classification’ refers to the organization of plants into groups that reflect their evolutionary relationships as plant taxa which, prior to Darwin and the theory of evolution, involved the organization of mostly morphological characters as similarities and differences.

- We study plants through the broad range of scientific disciplines that fall under the heading of plant science (formerly the narrower discipline of botany). There is no current and widely accepted system of categories, principles and procedures for the study of the topic ‘plants and people’

Epilogue

- summary of the articles on classification, plant classification, and plant-people taxonomy -

Classification

Classification (the ordering of our experience of the world) is, in its most general sense, a process of orientation to the world that is an expression of biological agency in its mindless, unconscious, conscious, and cultural forms.

Though the mindless short- and long-term process of adaptation to environmental surroundings is part of the life of every organism, it is the human aspect of classification that concerns us here.

Purpose

The form of any classification depends on the purpose (reason, intention, goal) for which it was created. Once the purpose is established then it becomes possible to develop meaningful analytical categories that fragment the object of study in ways that assist understanding and explanation.

Structure

For any process of classification there are several elements. Among the units of mental processing (representational units) there are: the objects being classified - the relata; the grouping criteria or properties - the selection criteria; the criteria for the arrangement of groups - ranking criteria; and the representation of the relationship between groups formed in this way - the classification system.

All elements are subordinate to the overall purpose of the classification.

Mental processing

There are, in principle, at least four mental predispositions that make meaningful experience possible. All of these are subordinate to the purpose of the classification.

The mind categorizes the world into meaningful representational units (mental categories); it focuses on a limited range of these objects at any given time resulting in a foreground and background mode of awareness; it groups these categories in various ways; and it ranks both categories and category groups in relation to one-another according to both conscious and unconscious priorities.

Human unconscious mental processing

For humans, environmental adjustment is expressed through all four major modes of agency: mindless, unconscious, individual conscious, or cultural (collective).

Groups of mental objects, their properties and relations, are united with others to become more inclusive groups, properties and relations. However, as the focus of our attention changes, so too do our classifications as the objects in one classification become the properties of another and so on and so forth in a process of incessant mental adjustment to our internal and external environments.

Human classifications

Though classification can proceed at the

In humans, classification as an intentional mental process, acts as both an unconscious and conscious decision-making tool whose elements take the intuitive form of objects, their properties and relations. Formal scientific classifications are public and progressive representations of the world that contribute to collective learning.

Human minds are constantly – both consciously and unconsciously – organizing their contents in a purposeful way. The unconscious ordering process is part of our inherited human nature, and it provides us with a coherent and meaningful experience that includes a practical representation of the world (our common-sense impression of ‘reality’ . . . our umwelt or manifest image).

When this becomes a deliberate conscious endeavour, as it does in science, we describe it using the formal term ‘classification’, this being a public process undertaken as a collaborative and progressive refinement of the relationship between categories within a particular discipline as just one facet of our collective learning.

There are an infinite number of ways of classifying categories, but the categories chosen in any particular situation will depend on the purpose of the classification. So, for example, the biological classification of organisms arranges them according to their presumed evolutionary relationships. Classifications are, in this sense, decision-making tools.

Though classification, in a general sense, is the conscious or unconscious investigation of the relationship between the objects of our experience (categories or concepts). More formally, classification becomes the conscious ordering or grouping of objects by criteria selected to achieve a particular end or goal. The study of classification itself – its principles, and procedures – is called taxonomy.

Categories are abstract entities usually denoted using names: they vary in degree of precision and clarity. A useful distinction may be made between classical categories whose defining features (selection criteria) are both necessary and sufficient, and the more common fuzzy categories whose meanings grade into the meanings of other categories. ‘Gold’, defined as an element with atomic number 79, is a classical category while ‘game’ is a fuzzy category with a family resemblance of characteristics that merges into other categories.

To be effective, our inherited mental processing must, of necessity, include at least four pre-conscious processes. The categorization of the world into meaningful units of representation (mental categories); a focus on a limited range of these objects at any given time (so that our minds operate with an experiential background and foreground); a classification of categories into various groups; and the ranking of categories and category groups in relation to one-another according to conscious and unconscious priorities.

Classifications are part of our reasoning faculty, not because they impose logic into our thinking, but because they introduce order by maximizing representational power. They arrange the categories of our experience into groups by using selection criteria that satisfy an objective or purpose and thus reflect the intentionality of biological existence. So, for example, I might wish to classify my friends using the selection criteria of hair colour, height, or sporting interests.

Every classification has three major components: its purpose (the reason why the classification was devised); the selection criteria used to arrange or group categories according to that purpose; and the structure or system of classification to be used. Systems of classification include hierarchies (see also language below), trees, lists etc. and it is important to be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of each system because, at the outset of a new project, we need clarity in our categories and their relations, so a proven methodology becomes a valuable asset.

We communicate our understanding of category relationships using the medium of language. We have in our minds a web of interrelated categories. We organize these categories into a linear sequence of words (spoken or written) – a string – according to the rules of syntax which, together with the rules of word formation comprise its grammar. Grammar is our (species-specific) solution for getting complicated thoughts from one head to another.

Words are arranged into phrases that are nested within sentences in the form of an inverted hierarchical tree using the principles of syntax. Thus, syntax uses a tree of phrases to translate a web of thoughts into a string of words. The listener then works backwards, fitting these words into a tree and recovering the links between the associated concepts. In other words, we structure language like a nested hierarchy in a boxes-within-boxes way with sentences containing substructures (phrases) that form an inverted tree when presented pictorially on the page.

There may be a connection between our intuitive hierarchical organization of language and our intuitive structuring of the world.

Language provides us with a symbolic representation of the world, its categories linked into a web of interconnected knowledge. One major task of science is to provide us with the best possible set of categories to describe and organize our collective learning.

Science has advanced by designating topics of study (academic disciplines) with a community of scientists that constantly refine the categories, principles and procedures used by that study.

When considering the world of plants and classification we place major emphasis on their scientific classification whose purpose or interest is their evolutionary relationships. Indeed, this is what most of us understand by ‘plant classification’ and it entails a well-understood set of classification categories and selection criteria. But there is another classification system whose purpose is to study, not the relationship between plants, but the relationship between plants and people for which we have no clear classification categories and selection criteria. This is the subject of the article on plant classification.

Glossary

category – any unit of experience that can be used for mental processing; the operational unit of mental processing

categorization – the mental formation of categories as units of representation

classification – the study of categorial relationships; the ordering of categories; the arrangement of objects into groups by selection criteria determined by the purpose of the classification; a decision-making tool. Classifications vary from being private intuitive mental processes to formally derived and communally agreed systems of representation

collective learning – culturally accumulated knowledge: shared information that is passed from generation to generation. Cultural information exists as memes that may be as simple as transmitted practical facts, or as complicated as innately comprehended body language and mental tools like language and mathematics. Historically the rate of accumulation of collective knowledge has accelerated exponentially through time facilitated, in part, by increasingly sophisticated technology.

focus – the restriction of our attention to a limited range of representational units so that, at any given time, our attention is divided into a foreground and background

manifest image – our common sense impression of the world including colors, smells, trees, cars, people, buildings etc. This impression may conflict with the scientific account of the world (cf. scientific image)

mentalese – the ‘language of thought’ that avoids the ambiguities of words and the many unnecessary articles, prepositions, and grammatical adjustments that are needed to create spoken language

purpose (taxonomy) – the reason for, or goal, of a classification

nested hierarchy – the taxa and their groupings are contained within other groups in a boxes-within-boxes fashion, like a Russian doll

plant species – (classification) the most practical unit of plant representation

rank (value)– the ranking (valuing or prioritizing) of objects relative to one-another within a classification system

representational unit – any object of mental processing

scientific image – The scientific image is what the natural sciences tell us the world is like. This impression may conflict with the manifest image or commonsense impression of the world (cf. manifest image)

segregation – the organization of experience into meaningful representational units, both those of cognition (concepts), and those of perception (percepts)

taxonomy – in its broadest sense, the study of relationships. While classification is the actual process of grouping categories, taxonomy is the study of the principles and procedures that allow this to occur

umwelt – the environment of significance to any organism: those factors important for its survival, reproduction, and flourishing. For humans it is the commonsense world of everyday experience (cf. manifest image) that is mostly a consequence of our innate mental processing which is, in turn, a consequence of our uniquely human evolutionary history

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . revised 11 January 2021

. . . substantially revised 28 June 2022

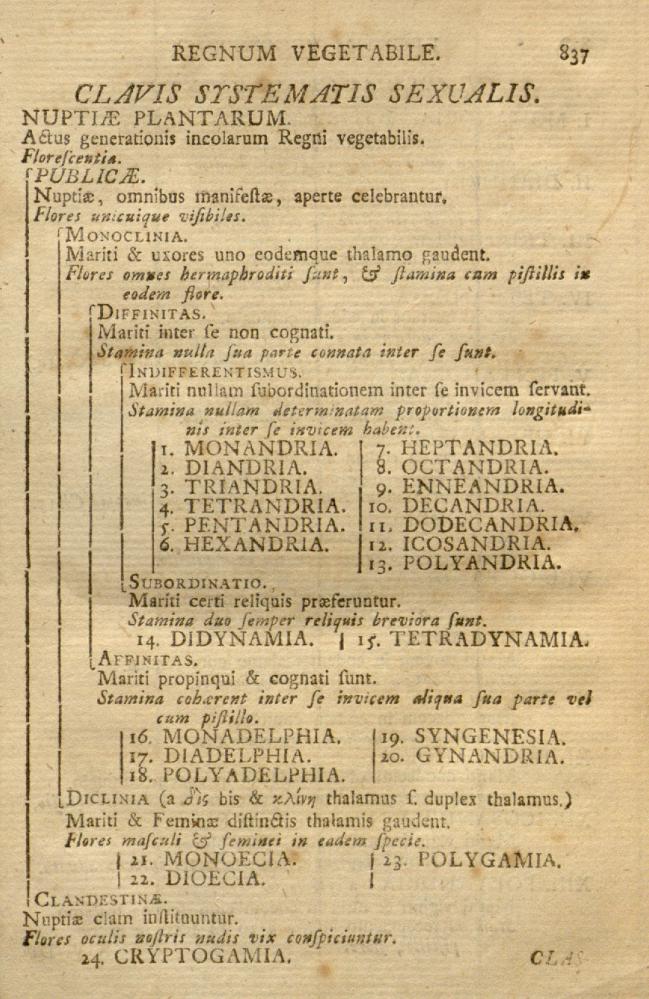

Scientific classification.

A flowering plant phylogeny of 2020

including the then recognized 435 plant families

The colours of the branches and the outer circles represent the major angiosperm clades (branches of the plant evolutionary tree) as indicated in the caption (ANA, Amborellales + Nymphaeales + Austrobaileyales). The illustrations around the circumference show 32 plant families and their position in the tree.

The flowering plants (angiosperms) arose in the Early Cretaceous about 145–100 million years ago, supplanting the earlier ferns and conifers (pteridosperms and gymnosperms). Palaeobotanical evidence indicates that this replacement was gradual, flowering plants not becoming dominant until the Palaeocene about 66–56 million years ago. The timing, geographic sequence, and plant composition of this diversification remains uncertain. There appear to have been substantial time lags, mostly around 37–56 million years, between the origin of families (stem age) and the diversification leading to extant species (crown ages) across the entire angiosperm tree of life. Families with the shortest lags occur mostly in temperate and arid biomes compared with tropical biomes. The ecological expansion of existing flowering plants, it seems, occurred long after their phylogenetic diversity originated during the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution.

Courtesy public domain license. Adapted from the originals provided by S.M., the Peter H. Raven Library/Missouri Botanical Garden and the Mertz Library/New York Botanical Garden