Science & morality

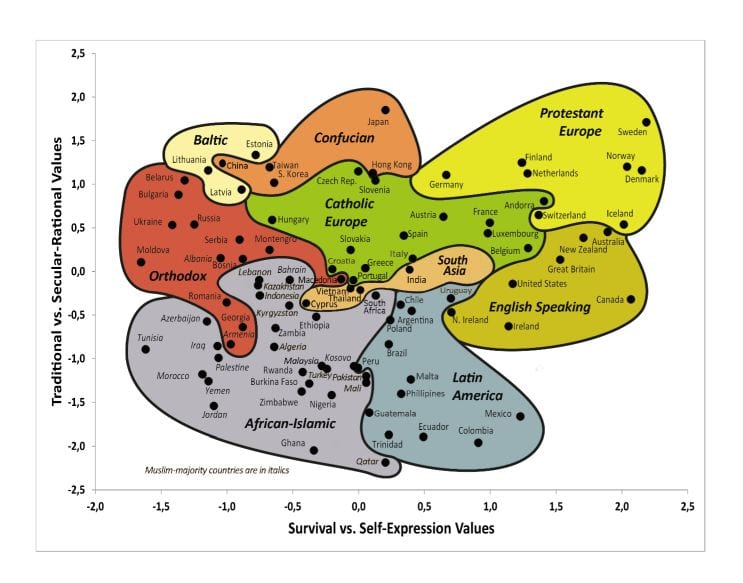

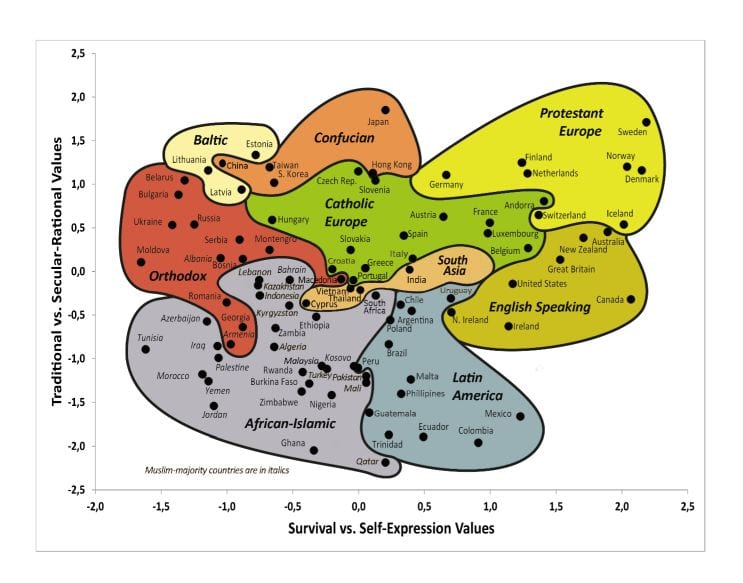

Inglehart-Wetzel graph of world values

World values, grounded mainly in religious belief, are also influenced by the advance of science. What is the relationship between religion and science – what influence does science have on our values?

Life is better than death

Health is better than sickness

Abundance is better than want

Freedom is better than coercion

Happiness is better than suffering

Knowledge is better than superstition and ignorance

Steven Pinker ‘Enlightenment Now’ p. 248

‘Values reduce to facts about human well-being’

Sam Harris ‘The Moral Landscape’

Yuval Harari – a delightful (and unwitting) double-entendre in the debate ‘Nature vs. Humanity’ with Slavoj Žižek https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jjRq-CW1dc

Edward Wilson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jjRq-CW1dc

Steven Pinker

Several articles examine the reasons for us behaving as we do – the various forces and principles that are part of our human nature and therefore have a strong influence on our actions. The article on biological values describes the way that, unsurprisingly, our conscious and deliberate human behaviour is grounded in our unconscious and mindless biological history. The article on moral psychology extends this theme by looking at unconscious human motivation, the psychological origins of our human moral intuitions. The article on morality is an introduction to ethics as the study of the principles and rules that govern right action with a brief overview of the world’s major moral theories. Two articles, purpose & value and science and morality explore the relationship between the world of science and the world of values. All these articles are then drawn on to investigate the role of practical or applied environmental ethics in our collective human management of sustainability and the world environment.

Introduction – Science and Morality

Science can play a major role in the future of our planet because of its connections with technology. But what role can it play in policy-making – isn’t that a different matter altogether? After all, even if we agree about the human influence on climate change, the remedial policies we adopt will depend on our values. And values have little, if anything, to do with science. Values are a totally different ball game . . . aren’t they?

Can science tell us what to value both as individuals and communities: can it tell us right from wrong? Can science inform ethics in any way at all, and if so, then how?

The Great Divide

There is a long-held western philosophical belief that our world can be divided into two broad domains of experience and discourse – the scientific and the moral . . . the world of facts and the world of values. Science deals with the empirical universe, the way the world is – and it is descriptive. Then there is the domain that includes religion, morality, and aesthetics – which are about moral meaning and value – they are normative.

Evolutionary biologist and popular author Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002) in his book Rocks of Ages (1999) described these two domains in grandiose terms as ‘non-overlapping magisteria’.

This distinction – between the way the world is and the way it ought to be – has long served as an uneasy territorial boundary in academia and elsewhere.

Scientists appreciate this distinction because it supports the idea of science as truth untainted by human subjectivity and any form of ideology, knowledge that rises above the herd. With science thus confined it was possible for religion, ethics, and aesthetics to manage their own intellectual territory without fear of challenge from empirical claims.

This long-held Western view of two distinct worlds, one of fact, and one of value – the latter depending on human mental states and conscious deliberation – has come under increasing strain. This has come, partly as a result of the failure, after several decades of serious investigation, to establish a clear demarcation between science and non-science, and partly from the realization that science informs the humanities in a multitude of ways. That, indeed, our desire to pigeon-hole academia into clear and distinct categories is doomed.

Fact vs Value

So, on the one hand there is the widely accepted view that values are created by, and confined to, human minds (values are subjective): there can be no mind-independent values. Then, on the other hand, there are alternative views like those expressed on this web site: that human agency and human values are a highly evolved (minded) form of (mostly mindless) biological agency and biological values (values are objective).

The distinction can be expressed in another way. On the one hand we have mental states called beliefs relating to the external world and these, when thoroughly tested, count as scientific knowledge or objective facts. And on the other hand we have mental states like desires, intentions, attitudes, and concerns that are directed towards changing the world to our liking: these are the values that orientate us to the external world and provide motivation for action.

Expressed like this we might say that science is about the external world and what lies outside our minds while values are about our inner world, that is, what is in our minds. Or again, values are human constructs, the world itself does not have values, only humans do . . . facts reflect the world: values are about changing it. This line of thinking quickly becomes an ‘inside/outside’ discussion reminiscent of the nature vs nurture debate.

The philosophical basis for this fact-value dichotomy is often attributed to Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), who observed that a deductive argument must have values in the premises if it is to have values in the conclusion . . . that no normative conclusion can be validly derived from factual premises.

In other words, we cannot move deductively from the way the world is to the way it ought to be. Hume’s claim gave rise to a famous dictum in philosophy known as ‘Hume’s guillotine’, which expresses this more succinctly as a logically necessary condition: ‘You cannot derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’. That is, a moral judgment, a prescription, or value cannot be derived from something factual, a description: you cannot make judgements about what should be based on what is. And ‘ought’ is ethics, not science. We cannot pass logically from ‘murder causes suffering‘ to ‘murder is wrong‘ without the insertion of the moral statement ‘suffering is wrong‘. Empirical evidence cannot decide such a question.

The significance of Hume’s claim, if compelling, is that it creates a clear demarcation between fact and value and, by extrapolation, between science and ethics. It is also influential in creating a boundary not only between the sciences and humanities but, indeed, between humans and nature. It is a precept that has a firm grip on the Western intellectual tradition, which is inclined to treat facts as empirically verifiable – true or false – and values as more a matter of sentiment – of feeling and attitude.

The argument is appealingly simple and straightforward: values, of whatever kind, arise in minds and are therefore quintessentially human. When they are the result of shared and reasoned deliberation, as they are in codes of behaviour, we call them ethics.

Immanuel Kant (1724– 1804) seemingly agreed with Hume by saying in his Critique of Judgment (First Introduction, X240) that ‘. . . to think of a product of nature that there is something which it ought to be . . . presupposes a principle which could not be drawn from experience (which teaches only what things are).

Much later, Cambridge philosopher G.E. Moore (1873-1958) in a slightly different context claimed that any connection between a normative property (like goodness) and a natural property (like pleasure) is open to doubt (his ‘naturalistic fallacy’).

This gulf between magisteria is still a powerful influence today as a carry-over of the former philosophical school of British Empiricism.

In the 21st century, about 150 years after Darwin, it is now evident that human values, however refined by reason, are nevertheless grounded in the universal biological values that are expressed most succinctly in the biological axiom. As Hume himself perceptively observed, ‘Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them‘ (Treatise on Human Nature 2.3.3 p. 415), this being an acknowledgement of the grounding of human value in the mindless demands of the biological axiom, no matter how they are constrained by reason.

With the decline of religion, we now realize that it is to biology that we must look for the foundations of morality, and that our reasoning faculty is just one, albeit extremely important, component of the biological toolbox that we use to evaluate and prescribe. Even the uniquely human institutionalized ethics, made possible by uniquely human language and reason, is nevertheless ultimately grounded in biological values.

Both Kant and Hume preceded Darwin by about a century. Their thinking preceded Darwin’s theory of natural selection at a time when it was assumed that species were discrete and immutable, not a consequence of descent with modification from a common ancestor. This was also a time when physics was regarded as serious and hard science with biology its soft barely scientific extension. Like Yuval Harari (see quote above) we can acknowledge the difficulty of obtaining values from nature if we think of nature as mountains, planets, and stars. But organisms are saturated with goal-directed (purposive) behaviour that demonstrates mindless values.

Just like purpose and design in nature, values ‘bubble up from the bottom, rather than trickle down from the top‘ (cf. philosopher Daniel Dennett when referring to design in nature).

Deriving ‘ought’ from ‘is’

Normativity is about evaluations of right and wrong, good and bad, better or worse. How can we possibly infer the way things ought to be (a subjective value) from the way things are (objective scientific facts)? How can a moral judgment, a prescription, be derived from something descriptive?

Biological values derive from the propensity of all life to survive, reproduce, and flourish (the biological axiom). The universal biological axiom is, simultaneously, a statement of both fact and value. It describes what organisms do (fact) while also describing their observable (objective) goals manifest as a behavioural orientation which, in human-talk, we can refer to as an expression of ‘biological value’, like a mindless ‘point of view’. The quotes here indicate the lack of vocabulary and struggle needed to convey the close and real connection that exists between mindless behaviour and its evolutionary development, behaviour that is guided by minded representation.

In this way all life is an expression or manifestation of value.

The meaning of ‘value’ as something that is mind-dependent is here being challenged. The claim is that the notion of ‘value’ is more scientifically coherent when applied to all living organisms, not just humans (see life as agency and biological values and human-talk).

As a matter of fact, organisms do not exist passively in the world like rocks. As part of their biological nature their behaviour demonstrates that they have a propensity for (they ‘value’) some things over others – they act in purposive and goal-directed ways. This is part of the flexibility of behaviour displayed by all organisms. As circumstances change, so does their behaviour.

Hume would no doubt point out that the biological axiom is not a logical necessity. The survival, reproduction, and flourishing of organisms is no more logically necessary than is our own human survival etc. And to regard such values as ‘good’ is wildly overstepping the mark.

The difficulty here is that to deny the biological axiom is to deny life itself: the values expressed in the behaviour of organisms are not logically necessary, but they are biologically necessary. If life did not express these values it would not exist. It is these values that motivate or drive the behaviour of all living things even though humans, having the capacity for mental representation, can use reason to override (but not eliminate) them.

The feeble filtering valuation of physical constants that applies to inanimate nature, that reduces possible outcomes, takes a giant stride with the emergence of agential matter that can reproduce itself (life). Out of the mindless values expressed in the behaviour of non-sentient organisms there evolved the human capacity for conscious deliberation that could override our biological inclinations.

Reason is not separate from our biological values, but superimposed on them and ultimately grounded in them. If reason is ‘the ability to use knowledge to obtain goals‘ (Pinker 2021, where knowledge is defined as justified true belief) then the ultimate goals of human reason are co-extensive with those of the biological axiom. In this way, perhaps contrary to our intuition, reason becomes a thick concept: that is, it is a concept that combines evaluative and descriptive elements (like wellbeing, health) with thin concepts being purely evaluative, like ‘dood’ or ‘ought’. The functionality of the mind is simply an extension of the functionality of nature, albeit a much more elaborate one.

Like the purpose so evident in biological agents, value proceeds from within living organisms as an imminent faculty: life and value are intimately and inexorably intertwined. Reason then, through language, takes value into the institutionalized human sphere, as ethics.

The common-sense support we intuitively feel for Aristotle’s biological imperative and Steven Pinker’s moral injunctions at the head of this article can be understood, not in terms of the arbitrary subjectivity of our human values, but as the biological necessity that we conform to objective (mostly mindless) biological values of the biological axiom, even when modified by their servant, reason, a biological evolutionary add-on. Indeed, we cannot get ethics out of biology . . . because it is biology on which our ethics rests.

Human agency and its values are best understood scientifically as a highly evolved, specialized, and minded form of objective biological agency.

Facts have moral significance as they impact on universal and necessary biological values as mediated by human reason. Pointing out that our human valuing of survival, reproduction, and flourishing is a matter of subjective orientation because it is not logically necessary is philosophical chicanery. We do so based on the fact that we are living creatures whose behaviour, like that of all organisms, observes the biological necessity of the biological axiom.

Whether organisms (their processes, structures and behaviours) achieve their goals depends on circumstances in the objective world, on the way the world is. To achieve our goals we must change the world from the way it is to the way we would like it to be or, to use more moral language, the way it ought to be.

The point about us deriving ought statements from is statements is less about logic and more about biological necessity which can be modified by reason but not eliminated.

We cannot pass logically from ‘murder causes suffering‘ to ‘murder is wrong‘ without the insertion of the moral statement ‘suffering is wrong‘. But survival, reproduction and flourishing are what it means to be a living being – they are a factual biological necessity without which life could not exist. Murder is unpopular, not because we have an ethics saying that as a matter of logical ethical principle murder is ‘wrong’ and therefore we ‘ought’ not murder. Instead, we do not murder because it is contrary to the objective and biologically necessary universal biological values that are part of what it is to be a living organism.

Murder does not break a logical connection in an ethical theory, it resists the biological necessity expressed in biological values.

Ethical naturalism & the biological axiom

Ethical naturalism replaces putatively subjective concepts like ‘good’ and ‘right’ (derived from human minds) with empirical and observable factors like happiness, wellbeing, flourishing, health, survival, justice, freedom etc. (derived from the world). Pain hurts, therefore pain is bad. Here the moral notions of right and wrong are being replaced by empirical synonyms. Thus, ethical naturalism reduces ethical properties, like ‘good’, or ‘wrong’ with non-ethical properties like ‘pleasure’ or ‘pain’.

Many ethicists maintain that such substitutions cannot be made. ‘Right’ and ‘wrong’, and what we ‘ought’ to do are absolute notions like divine commands, it is statements like these, and the principles that underpin them, that define what it is to study ethics and morality.

This view devalues all relative notions and since empirical synonyms are always relative to circumstance, they are not relevant to ethics. Put simply, increasing wellbeing or pleasure is not a moral endeavour.

There is also a widely held view among ethicists that absolute moral truths simply do not exist, and that this is why we try to derive morality from the world.

Certainly moralities can be established when there is subjective agreement about morality because agreement becomes an objective fact. We all agree that wellbeing is ‘good’ and that pain and suffering is ‘bad’. However, truth is not determined by democratic consensus and that falling back on empirical synonyms is a subjective process: it is not objectively true that wellbeing is good.

It is often claimed that value-terms are part of our prescriptive moral language that commends certain behaviour and cannot be reduced to descriptive terms. As already established, the biological axiom is simultaneously a statement of both fact and value. As a statement of fact, it is the best we have as an objective foundation for a code of behaviour, bearing in mind that, for humans, biological values translate in minded terms to concepts like happiness, wellbeing, and flourishing. This is not a claim that ‘the way things are is always the way they ought to be’ it is a branch of ethical naturalism that replaces the moral language of ethics (‘good’, ‘evil’, ‘bad’, ‘right’, ‘wrong’) with that of value based on biological preferences that are, in the case of humans, modified by reason.

The scientific field of medicine is founded on the general principle and goal of maintaining human health. Our desire for health is not a value that we feel should be doubted, or subjected to serious philosophical debate. When I have a severe toothache I do not ensure that a visit to the dentist is deductively justified: I simply make an appointment. We do not go to the doctor and ask her to recommend ways to make us ill. Medicine does not waste its time trying to persuade us that being healthy requires logical justification – it is self-evident, our desire to survive is a biological fact, it is the way we are, not the way we ‘ought’ to be.[9]

Sadly, circumstances may occasionally arise when life (survival, reproduction, and flourishing) is not the preferred option. This is the logical exception that means my desire for health is not a logical necessity – it is an ‘ought’, not an ‘is’.

The lack of logical necessity may be of interest to philosophers, but it has no relevance to the reality of biological necessity. We approach the goals of the biological axiom as a matter of biological necessity – because that is what biological agency is, it is the way we are.

Author Sam Harris in his The Moral Landscape (see quote above) argues that science should, in principle, be able to tell us how we ought to live our lives based on general common-sense universally accepted (objective) principles like that of ‘health’. This is the philosophical challenge.

Science cannot tell us what we ‘ought’ to do in a moral sense, but it can examine behaviour that conduces with the biological values of the biological axiom as modified by reason, which is the way the world is. Like the biological axiom itself this is both a fact of the world and a value. It is a fact that is also a guide to behaviour. However, for humans using reason this often leaves us with many paths to particular goals and the messy business of deciding which path to follow, illustrating the practical utility of absolute ethics.

Naturalistic values deny the existence of ethics, and the notions of right, wrong, and moral obligation, replacing them with an examination of the conditions that are conducive to the existence of life which, in the case of humans, is uniquely determined by reason. Naturalistic values substitutes the language of value for the language of ethics. It is not a form of ethical naturalism because it is not about ethics, it is about naturalistic values.

Human flourishing & well-being

Humans, like all organisms, manifest the behaviour described by the biological axiom – because that is (factually and therefore objectively, the way they are biologically constituted . . . it is the way we are. However, evolution has given us minds whose reason distances us from these biological drivers.

Rational objectives are in concert with the biological axiom but take a slightly different form. It is the human goals of happiness and wellbeing that are the more obvious face of survival, reproduction and flourishing – the universal values based on biological necessity. The fact that they are not logically necessary is of little interest since the denial of life is inconsequential, it does not make sense.

Human reason and consciousness are an evolutionary development that gives humans a self-awareness, placed in both context and circumstance, that is not available to other organisms. Self-reflection opens the way to self-correction as a form of adaptation and behavioural adjustment.

This rationally minded form of conscious adaptation is not available, even to other sentient animals. We can consciously construct systems of belief that use standards of evidence and we can devise codes of behaviour that use rational principles that are grounded in our biological make-up.

Having life goals entails the rational consideration of how to achieve these goals in the objective world. This matter is given consideration in the articles on happiness, moral psychology, and within the subjects of behavioural genetics, evolutionary psychology, and practical ethics can provide real assistance in guiding our behaviour towards the globalization of life goals.

Science can assist the process of natural valuation by providing factual information about the world and a vast toolbox of methods and procedures for processing information.

Biological values

There is something special about both the capacity and will to live. Mindless and mechanical natural selection has ensured that survival and reproduction[12] are key characteristics of all organisms whether sentient or not: it is what living organisms do, and it is what makes them different from rocks. It is therefore legitimate to speak of purposes even when there are no intentions.

If a human being places no value on their life then we believe that something is seriously wrong. It is clear that a living organism is different from a rock, a major difference being its ‘directiveness’, its non-intentional purpose. The difference between this kind of purpose and that of intentional purpose is a matter of degree (where does intentional behaviour cease along the continuum between sentience and non-sentience?) and I agree with Aristotle‘s idea of purpose … if a line is to be drawn somewhere then it should be between life and non-life not between the intentional and non-intentional. Accepting this does not mean that the distinction between intentional and non-intentional is irrelevant or that metaphorical attribution of conscious intention to non-conscious organisms is scientifically OK. What it does mean is that purpose-talk is OK even if intention-talk is not.

Looking at purpose has made us realize that there is indeed an ultimate aim, an ultimate value for all living things, the teleonomic purpose of survival and reproduction. To do that well, organisms must flourish. Evolution does not take account of the happiness and suffering that might be entailed in survival and reproduction – it simply ‘counts the numbers of organisms that are still standing at the end”’. Survival and reproduction are purposes while human intention tends not to look so far – our more direct conscious rational intention sees flourishing and happiness as ultimate goals as what it means to flourish. This takes us into the world of ethics.

For Aristotelian evolutionary biologist Leroi the ultimate question for biology – ‘why do organisms want to survive and reproduce?’ has the answer ‘because natural selection made them so.’ He maintains that ‘Aristotle’s organismal teleology is imposed on recalcitrant matter’ what we have called a form of intrinsic teleology while Darwin shows that ‘it emerges from it’. ‘Darwin is an ontological reductionist; Aristotle is not’.[10] Leroi appears to be claiming that Darwin perceived biology as complex chemistry and physics, that he was a ‘reductionist’. By contrast Aristotle saw life as a special kind of ordering of matter that was in some sense purposive (telos): he was a ‘holist’. Aristotle made a further claim that organisms strive to survive and reproduce and ‘participate in the eternal and the divine’. Perhaps here he was expressing the sentiment of wonder combined with an appreciation of the continuity of life akin to the ‘immortality’ of genes so central to Dawkins view. He was not a transcendentalist so this was unlikely to have been a statement of religious belief.

The article Ethics and sustainability discusses how the biological purpose of survival, reproduction and flourishing as interpreted by ethicists through the notion of happiness must engage with the material world in such a way that people can make a practical contribution to the project of human flourishing through the kinds of ideas promoted by sustainability.

In the article on purpose it is argued that it is legitimate to see purpose in nature – to claim that the genetic code and the directive behaviour of communal insects are for something, they have a function, even though the function is not a conscious intention but something that has resulted from the mechanical and mindless process of natural selection. Once we accept this contention then we can also say whether functions are good or bad, whether health is good or bad and whether a heart beating strongly or feebly is good or bad, desireable or not. If the function of life is to survive and reproduce then a healthy pumping heart is all to the good: it is not a matter of indifference. Survival and reproduction (evolutionary fitness) can thus be argued as the ultimate justification for moral behaviour.[4] However, morality always wishes to take an (objective) overview: how do we square the following statements ‘Always pursue happiness’, ‘Always persue self-interest’, ‘Always pursue evolutionary fitness’, ‘Always pursue the greatest happiness of the greatest number’, ‘Always pursue your moral intuitions’. But if something is part of our nature, biology or evolutionary make-up does that mean that we ‘ought’ to do it?

It may also be claimed that evolution, our biology and moral intuitions have nothing at all to do with morality – morality is about objective and detached decision-making unimpeded by such factors: our natural inclinations are precisely what morality tries to overcome.

Commentary

The view presented in this article might be regarded as a form of value realism, backed up by secular empiricism as our best use of reason, logic, and evidence.

When asking the question, where do values come from, how do they arise? the traditional answer, that they were given to us by God, will no longer do. We then appear to be left with only two possible general alternatives: they arise out of our biological nature, or they arise out of our reason – or both, bearing in mind that our reason must be part of our biology.

All organisms exhibit behaviour that expresses values in the form of goals to which they are drawn. Our best summary of the multitude of these goals, and their ultimate ends, is that they are directed towards survival, reproduction, and flourishing. These three foundational drivers of all organic behaviour provide a definition of biological agency and ‘values’ that are universally displayed in the behaviour of living organisms (a biological axiom).

Out of this biological foundation evolved the conscious human mind capable of the rational deliberation and language that made the formalization of institutionalized codes of behaviour possible. Human values thus appear to derive from both strong internal and individual intuitions or instincts grounded strongly in biology, and external sources of communally agreed codes of behaviour that are attributed to reasoned debate.

Though reason offers the possibility of extreme abstraction and detachment it evolved as a tool that ultimately supports the goals of the biological axiom which, when transposed into categories of the mind, might be referred to as the will seeking the goals of happiness and wellbeing

The biological axiom is not a statement of the way things ‘ought’ to be, but the way things are. It is a statement of fact. It is simultaneously a statement of value in the sense that it describes an orientation or propensity of behaviour. However, this orientation of behaviour is not prescriptive, it does not say that this is the way behaviour ‘should’ be. That is, there is a strong sense in which the biological axiom describes behavioural values in a factual way (value realism) that do not make ethical judgements about right or good: it is not prescriptive.

. . . substantive edit – 27 July 2022

. . . added discussion of ethical naturalism and naturalistic values – 30 July 2022

Inglehart-Wetzel graph of world values