Scientific communication

Wisdom is shown in clarity not obscurity

Euripides, Orestes: spoken by Menelaus line 397

The sowing and planting of ideas into an orderly series, as opposed to just living off the careless ideas one finds in daily experience, is pleasurable in itself

Thomas Hobbes

The old stereotype of the scientist as a white-lab-coated bespectacled nerdy introvert male swanning around his laboratory with an air of daffy dissociation from the real world . . . has gone.

Nowadays a scientist is expected to convey highly technical and specialist research in a clear and engaging style that can be understood and enjoyed by everyone. After all, it is OK to be a geek . . . but your research grant depends on the impression you create as a person in the flesh . . . and even more on the way you express yourself in writing. This is a tough call, especially when, for some of us, the greatest literary challenge faced on a daily basis is some creative texting (lol).

There are many general style manuals available including books dedicated specifically to science writing.[11][17] But of all these I strongly recommend one written by a scientist – Steven Pinker’s The Sense of Style (2014) which adopts a refreshingly relaxed approach to writing protocol.

You can read this book for yourself – all I shall touch on here are a couple of his main points, one which he refers to as ‘classic style’ and the other ‘the curse of knowledge’.

Classic style

In writing for a general audience Pinker suggests clarity, simplicity, and a conversational style (writer and reader as equals) drawing the attention of the reader to something in the world that they may not have noticed before. To hold the reader’s attention requires engaging but restrained prose, putting aside philosophical and other complexity. The supreme skill of this kind of writing is not to dazzle the reader with the writers depth of knowledge, linguistic brilliance, or profundity of insight but to express an argument or thought in a simple way and in an ordered sequence using examples that clarify what is being said. When done well the hard work needed to achieve this end result becomes totally invisible … only the writer knows the enormous effort that was needed behind the scenes.[15] Classic style looks to its effectiveness by simulating two of our most natural acts: talking and seeing.[16]

The curse of knowledge

The ‘curse of knowledge’ is an expression coined by economists in 1989 to convey the difficulty experts have in considering something from the perspective of a person who does not know what they know – an apparently obvious point but one ignored by many scientists when they talk to people outside their peer group. There is a skill in finding the balance between giving patronisingly long explanations – or no explanations at all.

All-in-all a passage of writing is a great opportunity for a scientist to be artistic: it is a designed object with sections, topics, themes, actors, and an overall arc of coherence. Like any formal work of art it must have harmony, balance, and appeal – which requires careful crafting with attention to detail. The reader is your judge, so be friendly as well as informative.

Scientific detachment

We, as scientists communicating our work, are balanced on the horns of a dilemma. On the one horn we are expected to be pillars of objectivity, fixing the world with a cold gaze that is unmoved by human frailties and distractions. But, on the other horn, we are told again and again that it is the frosty detachment of science that has contributed to our lack of connection with the natural world: we might ‘know’ but we do not ‘care’. science arose and flourished in the West and it is the West that cares least about its impact on nature, it is sometimes said.

How can we get people interested? This is not easy. We all know the bright and breezy presenter with an easy and relaxed manner, all familiarity and a ready serving of jokes. One method is catharsis, the relieving of tensions by using humour to expose and purge contradictions, injustices, and fears, and give an airing to general sources of confusion, pain and suffering. Take care in attempting this as you can just seem false (‘What a surprise, I’m just like you, but really smart and with a great sense of humour’). Another device used to capture your attention and heart and, incidentally, a pet hate of mine, is the use of artistic license to capture a sense of urgency, the personal here and now that we associate with fictional narratives:

‘Albert Einstein gazed wistfully out of his window into the clear blue sky. Yet another week of frustration with nothing to show for his efforts. But ‘Perhaps’, he mused, ‘this week will be different’. . .

Read on to see if Albert can deliver the goods . . .

The art of persuasion

There was a time, not so long ago, when books were scarce or non-existent and few people could read or write. In those days you would sink or swim among your fellows based on the impression you created in conversation and public debate. The pen may be more powerful than the sword, but only if people can read and write.

In the world’s great ancient civilizations the art of verbal persuasion was therefore carefully nurtured and this was done through the discipline of rhetoric. Written reference to these skills can be found as far back as Akkadian wrings from Mesopotamia dating to about 2285–2250 BCE and the Neo-Assyrians of 704–681 BCE and in the Chinese writings of Confucius (551-479 BCE). Eloquence was deeply admired because it would command respect and it was therefore taught as a system of rules (the verbal tricks of the trade).[1]

As democracy (not like today’s liberal democracies) became a part of life in Ancient Greece, much of public and political life turned on decisions made as a consequence of competitive oratory in front of large crowds and in the law courts. This is why rhetoric became a compulsory part of ancient Greek education that was continued through Roman times when we hear of great public speakers like Cicero and Julius Caesar (who was tutored in oratory by a Greek) and this continued into the Middle Ages. Privileged medieval students studied philosophy which was essentially another word for all knowledge. Their studies began with the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric – from which we get the word trivial, meaning ‘easy’) which was a preparation for the more difficult quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) that together became known later as the seven liberal arts. With attention to detail you would then avoid sgrammatical errors or solecisms as they were known.

So what exactly is rhetoric? As usual Aristotle gives it to us straight between the eyes, defining it as the critical art of persuasion through logos (reason), pathos (emotional appeal, imaginitive identification), and ethos (credibility, trustworthiness, authority). Credibility was demonstrated through wisdom and communication skills combined with integrity, sincerity and a genuine desire to engage. Of course every speaker needs to convey the truth but, said Aristotle, rhetoric ‘… adds the necessary sparkle to the diamond of truth’ thus demonstrating by example his mastery of the subject.[18]

The most effective approach in both written or spoken communication was epideictic rhetoric. This was a preliminary ‘feeling-out’, or ‘softening-up’ of the audience before launching into a cause or viewpoint. For example, the speaker might use some form of praise (a panegyric, encomium, or eulogy). Sometimes the role of the speaker was already defined so the audience might be expecting polemics (the uncompromising statement of a single point of view), apologetics (the defence of a particular position), or dialectic (logical comparison of views often represented as the statement of a position, the thesis, its opposing view, the antithesis, leading to a synthesis – which might then serve as a new thesis).

For most of us rhetoric is a distant echo of a long-abandoned classical education. In the 17th century we hear the first mutterings of criticism of the formal, no doubt statesmanlike but in all probability ponderous and pompous, manner adopted by people in public life. Wit, man of letters, and preacher Thomas Sprat (1635–1713) derided ‘fine speaking’ suggesting that public communication should ‘reject all amplifications, digressions, and swellings of style’ and instead ‘return back[4] to a primitive purity and shortness’. He was supported by English poet, literary critic, playwright and Poet Laureate John Dryden (1631-1700) who promoted communicating in a manner appropriate ‘to the occasion, the subject, and the persons’.[2] But some people never learn. Nearly two hundred years later Queen Victoria grumbled about Prime Minister Gladstone … ‘He speaks to me as if I was a public meeting’. We are only now emerging democratically from an era when education and high social status was immediately apparent through the wielding of an imperious and authoritative tone of voice combined with an exaggerated attention to precise diction.

It is difficult to find a happy medium (Aristotle said that the greatest moral virtue was moderation in all things). Today we still have a distaste for rhetoric because we associate it with pretension and call it ‘bullshit‘, but this is a pity. We all know people who try to assume authority by being supercilious, pompous, or opinionated, not to mention the guile of the silver-tongued salesman. The Greeks were wary of smoothe-talkers too, calling them Sophists and regarding them as insincere. But there are obvious benefits in expressing our ideas with clarity and appeal when we fumble along with ‘so, like, well, she goes … then he goes … isn’t it? … like, see what I mean?’ which would have made Gladstone blush.

In this article, in a few paragraph’s time, I will ask you to put yourself in the sandals of educated young Greek men (yes, Aristotle thought women were ‘imperfect men’ and should stay at home, which shows that even he can get it wrong sometimes) who, instead of tweeting and playing with their smartphones, would have spent their spare moments studying how to win friends and influence people using the skillful manipulation of words. I think that, like me, you will amazed by the insights into language and its use that are revealed by a short study of rhetoric.

Now, following Aristotle’s example, I’ll cease the paralipsis (omitting the important) and get to the point by being succinct. You can read about style yourself. In this article I’ll restrict myself to three areas I think are of special interest: the lexicon of literary devices that we can use to wrap up our message (literature for scientists); the conscious and unconscious use of metaphor, its advantages and pitfalls; and the idea of science as an objective value-free language.

Literary devices (rhetoric, word play)

What tools are available to the wordsmith? How can we spice up the language we use to sell ourselves?

I’ll try to give you here a synoptic tour of our language’s figures of speech (ways of using words without their literal meaning) and rhetorical tropes (strategies for improving the way language informs, persuades, and motivates).

Like the contemporary jargon associated with computers, ancient Greece had its own technobabble. Words associated with rhetoric seem to make up a disproportionate part of any dictionary so if, like me, you have dived for your dictionary again and again looking up the meanings of these words, only to forget them yet again, then I hope that putting some of them together in a comparative way, as follows, might be some help. It might not make you a better communicator but at least it should give you a wider view of the linguistic landscape.

Logology is the study of recreational linguistics which is the manipulation of letters, words, sounds, sentences, and meanings – so let’s get going!

Attention-grabbers

Perhaps the oldest way of ‘getting people in’ has been the use of personification or anthropomorphism – what John Ruskin called the ‘pathetic fallacy’. You make the natural world sound like a person and thus soften or enhance concerns about its threats and mysteries. If it is just like us then, hopefully, it is nice and friendly as well. You can tell them that galaxies ‘agonise’ or ‘weave intricate and majestic interstellar webs’, that plants ‘offer their gracious petals to the Sun’. But don’t get too carried away and become overwhelmed by autophasia, which is what happens when you are awestruck by your own cleverness with words.

One way of settling your audience and making them feel at home is through the anecdote as you recount an amusing or illuminating incident (‘On my way to the laboratory today . . .’). Tension can be set up in the collective mind of your audience by simply introducing anticipation – by using protasis, the ‘if’ of a conditional sentence; or by using antithesis, the juxtaposition of opposites (‘One small step for man: one giant leap for mankind’), and the caesura, aposiopesis, or pregnant pause (‘But, soft! What light through yonder window breaks?’) or the feigned doubt of aporia (‘I just don’t know where to begin …’).

You can immediately demand attention by posing a rhetorical question (one that does not really anticipate an answer) such as ‘Is science ultimately responsible for today’s environmental catastrophe?’ and you can maybe supplement this with erotesis, which is a rhetorical question posed with emphasis, like ‘Do you think I am joking?’ Although you are, in all probability, about to answer your own question, which is hypophora. Maybe use an epitrope by simply appearing to accept something but handing over responsibility for it (‘Who cares if climate change is real?‘).

Other devices to quickly get attention include the taunting barbs of sarcasm like the backhanded compliment when saying ‘You are early today’ to someone who is always late. One special kind of sarcasm is ennoia or damning with faint praise. Litotes employs understatement to make a point by stating a negative to further affirm a positive, often incorporating double negatives for effect. (‘He’s not bad looking’). You could use dialogismus by suggesting you are standing in someone else’s shoes (‘If I were you …’).

If you are not sure what to do then try parrhesia which is just speaking out directly and candidly and, if you slip up, use metanoia which is a way of retracting or weakening a statement by stating it in a better way (‘I saw it on Facebook: but it is listed in Encyclopaedia Britannica’). And in setting out your thesis or argument, remember the importance of distinctio (clarity and clear definition) and procatalepsis (anticipation of contradictions). But then, you can also introduce polysyndeton which is the deliberate use of multiple conjunctions to slow the rhythm of the prose and add solemnity – as in the Monty Python film The Holy Grail which parodies the scriptures . . . “And Saint Attila raised the hand grenade up on high, saying, “O Lord, bless this thy holy hand grenade, that with it thou mayst blow thine enemies to tiny bits, in thy mercy.” And the Lord did grin. And the people did feast upon the lambs, and sloths, and carp, and anchovies, and orangutans, and breakfast cereals, and fruit bats, and large chu[…]”

Sometimes stating things twice is enough to interrupt a sense of cosy familiarity as in a repeated phrase (tautophrase) like John Wayne’s ‘A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do’; a repeated name (tautonym) Ziziphus ziziphus for the Jujube Tree or Lang Lang for the famous pianist; or stating the same point in different ways (tautology) as in ’He is always making predictions about the future’, ‘HIV virus’, ‘Added Bonus!’ or even ‘$15 dollars’. A rhetorical flourish is achieved by the repetition of a word in phrases and sentences, either using the last word of one sentence for the start of the next, known as anadiplosis (‘Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering’) or at the beginning of one sentence and end of another, known as epanalepsis (‘The king is dead; long live the king’).

Sounds

Rhetoricians have a wonderful word for the rhythm and pattern of sounds, they call it prosody. We can all relate to this through the rhymes we enjoyed in childhood. Alliteration is the repeated use of the same sound in a series of words as in ‘Peter Piper Picked a Peck of Pickled Pepper’. Assonance, is alliteration that uses the rhythmic repetition of vowels (‘The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain’) while consonance uses the rhythmic repetition of consonants (‘Around the rugged rock the ragged rascal ran’).

Then there is the switching of different parts of words as vowels, consonants or sounds (metathesis). Examples are the spoonerism (‘The Lord is a shoving leopard’, instead of ‘The Lord is a loving shepherd’); cockney rhyming slang which swaps an entire sentence (‘The trouble and strife’ rhyming with ‘wife’); the malapropism which swaps a similar-sounding word for the correct one (‘He only goes running because of the feeling afterwards that comes from the dolphins’ – for ‘dolphins’ read ‘endorphins’ or ‘Sebastian was effluent’ – for ‘effluent’ read ‘affluent’).

Rather similar there is onomatopoeia, where the word imitates the sound it describes (‘buzzing’ of bees, the ‘plop’ of a drip of water) or a holorime, two different sentences that sound identical as in the immortal words of Jimi Hendrix: was it ‘Scuse me while I kiss the sky’ or ‘Scuse me while I kiss this guy’, this mis-hearing of words also known as a Mondagreen?

Sometimes there is just the simple pleasure of sound rhythms all mixed up, such as ‘’Malignant cancer’ is a pleonasm for a neoplasm’ and the old favourites ‘She sells sea shells on the sea shore, the shells she sells are sea shells I’m sure’ and my two favourite tongue-twisters, both best when repeated rapidly ‘I never felt at a felt hat that felt like that felt hat felt’ or, shorter but more tricky, ‘Red leather, yellow leather’.

Tropes

You can sound very literary and sophisticated by referring to a trope, which is a word, phrase, or image used for artistic effect. Tropes, unfortunately, can quickly descend into empty or difficult-to-define buzzwords or well-worn phrases (‘Mission Statement’, ‘Sustainability’). So, try to avoid banal or prosaic (unoriginal or unimaginative) oft-used truisms and platitudes like ‘Better late than never’ because it is just a small step into meaningless chatter as gobbledygook, gibberish, mumbo-jumbo or word salad. There are specialist kinds of chatter either associated with particular spheres of life or used for cheap effect, like psychobabble (‘Positive psychology’, ‘Empowerment’, ‘Self-actualisation’) and the similar cases of technobabble, legalese, corporatese, and so on.

You can also appear with-it by using a fashionable or well-known catch-phrase (‘Here’s looking at you kid’ Rick Blaine in the film ‘Casablanca’, ‘Life wasn’t meant to be easy’ Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser) provided you don’t end up in a double-bind, Hobson’s Choice[5] or Catch-22[6], which is a choice that is not really a choice at all, you are cornered (‘Heads I win, tails you lose’).

Avoid the trap of reminiscence (anamnesis) because you are likely to lose your train of thought (amnesia).

Word trickery

Since you probably do crossword puzzles you will already have thought of the anagram, the rearrangement of letters in a word or phrase to give a new word or phrase (William Shakespeare = I am a weakish speller) but there are all kinds of ways of mixing up letters and words for efficiency or effect. Here are a few distractions: an acronym is an abbreviation constructed from the initial components of a phrase or a word (North Atlantic Treaty Organization reduced to NATO) while a backronym creates a new phrase from an already existing word (Spam interpreted as ‘Something Posing As Meat’); acrostic, which uses the first letter or syllable of each line to create another and can therefore be used as a mnemonic or aide memoire which assists recollection; the pangram, which uses every letter of the alphabet (‘The quick Brown fox jumps over the lazy dog’); the heterogram or isogram which is a word with no letter repeated as in the 17-lettered ‘Subdermoglyphic’. Finally, there is the palindrome when the sentence is identical whether read forwards or backwards (‘Able was I ere I saw Elba’, ‘Lewd did I live & evil I did dwell’ (almost) and ‘Snug & raw was I ere I saw war & guns’.

Choice of words is crucial so don’t forget that among the many options is the informal use of slang. Portmanteau words blend the parts of several words or sounds to give new meaning, as in the languages Chinglish and Franglais, or the word ‘Eurasia’. However, try to avoid the use of the word ‘fuck’. Its pervasive presence in daily life has become known as ‘fuck patois’ and its versatility is truly amazing, even appearing as a noun, adjective, verb, and adverb all within a single sentence. Despite its versatility in daily intercourse (so-to-say) . . . it is not nice, and will not win you friends.

Special effects can be achieved by simply moving words around. Anastrophe is the reversal of the usual positioning of the adjective and noun (‘In times past’) while a short, sharp impact can be made with the aid of asyndeton, the removal of conjunctions while maintaining grammatical order (‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’).

Then there is hypozeuxis, where every clause in a sentence has its own independent subject and predicate, or repeats an element (‘I came, I saw, I conquered’). A rhythmic effect can be achieved by a criss-cross or reversing of ideas as in chiasmus ‘Ask not what your country can do for you: ask what you can do for your country‘. Then there is the swapping of entire words as in ‘The salesman bawls out his wares while a dachshund . . .’ which is rather risqué. Synchysis is the deliberate scattering of words to create confusion and force the audience to consider both the meaning of the words and the relationship between them as in ‘I talk and write, loudly and legibly.’

Then there are a whole series of logical permutations relating to the mix of word sound, spelling, and meaning: homograph, as words with the same sound and spelling but different meaning (‘Bear’, ‘Close’); homophone (multinym), same sound but different spelling and different meaning (‘Rays’, Raise’, ‘Raze’), and homonym, same sound and spelling but different meaning (‘Fluke’). If words have identical spelling but different meanings and pronunciations then they are heteronyms (‘With a number of injections my gums were getting number’).

Comparisons

In general terms we can speak either literally (factually) or figuratively (when we use non-literal language). Perhaps the best-known use of figurative language are the many idioms whose figurative meaning is different from their literal meaning as in ‘Don’t pull my leg’ or ‘It’s raining cats and dogs’.

It is difficult to describe phenomena in nature without drawing analogies (comparisons) of various kinds. In comparing two items we may make a direct comparison between them in the form of a simile (‘You are like an animal’) or a statement of identity rather than likeness, as a metaphor (‘You are an animal’) or, for effect, simply name one item with the other implied as in hypocatastasis (‘Animal!’).

Metaphors are sometimes further divided into metonyms as names or expressions indicating something else as when we use ‘Hollywood’ to mean the American movie industry or ‘Fleet Street’ the British press, while synecdoche is a sub-set of metonym in which a word denoting a part stands for a whole, as when we use ‘suits’ to refer to businessmen or ‘wheels’ for a car. Synecdoche is often used as a type of personification by attaching a human aspect to a non-human thing.

When fleshed out some of these devices become full-blooded literary forms. A fleshed-out metaphor becomes an allegory, like Plato’s allegory of the cave which compares people in a cave to the mental darkness of the unenlightened masses. Mockery as exaggerated imitation becomes parody, and when something occurs that is contrary to what is expected and therefore wryly amusing, we are dealing with irony, eironeia (‘It is ironic that the lifeguard drowned on a canoeing safari’). When shortcomings are ridiculed or lampooned, especially those of governments, it is known as satire which also makes ample use of sarcasm and irony.

For a stark confrontation of opposites we resort to enantiosis (‘Hasten slowly’, ‘Yin and yang’).

There will be times, though, when you commit catachresis by simply using the wrong word (‘Its time to mow the carpet’) and sometimes the comparison is just plain silly as with diasyrmus (‘Not saying ‘Hello’ is like spitting in your face’).

Meanings

Semantics deals with the meaning of words and it is anathema (a curse) for all of us that one word can have many meanings (polysemy), the art of manipulating these meanings in discourse being known as paronomasia, more familiarly referred to as a pun. But watch out for the Freudian slip which gives away what you are really thinking, so when she said ‘Would you like a cup of tea or some bread and butter?‘ he replied ‘Bed and butter.’

Some words can mean opposite things (‘Cleave’ meaning both ‘to stick together’ or ‘to separate’) so, using zeugma (syllepsis) the same word can be is used in the same sentence but with two different meanings (‘You are free to execute your laws and your citizens as you see fit’). And you can even create a new word as a neologism.

Sayings

Provided it does its job well, it is handy to have a quotable quote up your sleeve.

One of the best ways of getting attention is with a witty riposte or clever phrase as a bon mot, or simply nailing a situation with its most apposite word, its mot juste. There are another series of analogies: the parable as an, often religious, instructive story or moral tale. A parable employs humans while a fable is recounted with anthropomorphic and mythic animals, plants, inanimate objects, and natural forces. Simple terse expressions or truisms are known as maxims, adages, apothegms, aphorisms or proverbs (‘Too many cooks spoil the broth’, ‘More haste less speed’). When a saying is memorable for its wit or sarcasm the word ‘epigram’ is more appropriate (‘Carpe Diem’ meaning ‘Sieze the Day’ or poet John Dryden’s ‘Here lies my wife: here let her lie! Now she’s at rest – and so am I.’, which is also an epitaph or brief comment on death, but in this case not very politically correct. The statement on comedian Spike Milligan’s grave is presumably both an epigram and an epitaph (‘I told you I was ill!’). However, repeat these sayings too often and they lose effect, becoming a cliché.

Hypostasis is a special case, generally taken to be the underlying reality, as when people going about their daily lives suddenly realise they have been taking part in a television program: sometimes, giving something the character of a substance (‘Time was slipping through his fingers‘).

Overstatement

Pleonasm is the way that, in our excitement to emphasise an idea, we sometimes use more words than is necessary. We might, for example, talk about a ‘burning fire’. ‘Return back’ is a pleonasm used by Thomas Sprat (quote given above) while ‘Malignant cancer’ is a pleonasm for a neoplasm. Use of such words or expressions is needless repetition, redundancy or tautology while hyperbole is straightforward exaggeration or overstatement (‘I was waiting for an eternity’).

Archetypes are outstanding examples of people or ideas (Alexander the Great as an outstanding example of a military hero).

Also, try to avoid using unsubstantiated claims as weasel words (‘Most people say …’, ‘It is obvious that …’, ‘Evidence suggests …’).

Understatement

Sometimes we want to avoid causing offense or alarm by either using an innocuous word in place of one which might be more appropriate, or using some other method to avoid using an unpleasant word. This is frequent in the topics of sex, religion, bodily functions, disability, death, and race. We do this by using a euphemism (‘Collateral damage’ instead of ‘Killed civilians’ – sometimes also called doublespeek, ‘Pushing up daisies’ instead of ‘Dead’, ‘Downsizing’ instead of ‘Making redundant’). Occasionally we avoid the matter by simply hinting at what we mean by circumlocution, innuendo, or equivocation (‘Are you hungry?’) or altering the word slightly to give a mispronunciation of the word we are avoiding (‘Frickin’, ‘Oh, shoot’) or an abbreviation (‘Jeez’ for ‘Jesus’, ‘What the eff’n’). Political correctness is sometimes regarded as euphemism (‘Vertically challenged’ instead of ‘Short’). The antonym or opposite of euphemism is dysphemism (cacophemism) when something pleasant or innocuous is expressed in an unpleasant way (‘You old bastard’).

Take care – all these can seriously misfire.

Contradiction

Contradiction is expressed in various ways, not just as gainsay[9] or denial. It can use a word of opposite meaning, an antonym. An oxymoron uses contradictory terms together for emphasis (‘Military intelligence’, ‘Organised chaos’) while a paradox is a contradictory or illogical puzzle, superficially self-contradictory but conveying a truth such as (‘This statement is a lie’ or Socrates’s paradox ‘I know that I know nothing’). Synoeciosis is a coupling or bringing together of contraries, but not in order to oppose them to one another (as in antithesis).

Apophasis or paralipsis draws attention to something through its denial (‘Don’t mention the war’ or ‘Nobody has taken them, and anyway I wasn’t there, so I couldn’t have dropped the keys on the way out’).

Names

This brings us to many other kinds of name (epithet, moniker, cognomen) or – nyms would fill a whole page but it is useful to know about a few: synonyms as different words or phrases with the same meaning (‘purchase’ and ‘buy’) with opposite meaning words as antonyms (‘Black’ and ‘White’, or ‘Quick’ and ‘Slow’); ananyms, names with the reversed letters of an existing name like the Welsh village of Llareggub in the story Under Milkwood by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas which, when inverted, gives us ‘Bugger all’; aptronyms, names that aptly describe a person (‘Shorty’, ‘Nervous Nellie’), or a charactonym which aptly describes their character (‘Mr Angry’); pseudonym, which is a fictitious name (‘King Arthur’); or an eponym which is a name used for something other than itself, such as the eponymous botanical journal Muelleria. And don’t forget that a posh nick-name is a sobriquet.

An anaphor is a word used to refer to another (‘Eric will wash-up when he’s ready’).

Metaphor

As scientists we should be especially vigilant when creating or using metaphor (‘as-if’ talk). Metaphor can facilitate our thinking but also trip us up by creating seriously misleading mental representations.

For most of its life metaphor was treated as just another rhetorical device, one of many ways to colour language. But in 1980 cognitive scientists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson published ‘Metaphors We Live By’, an instant best-seller. In the Afterword of a later edition written in 2003, they outlined their thesis that metaphor is not just about literature: ‘Metaphors are pervasive, not just in language but in thought and action’, ‘There appear to be both universal metaphors and cultural variation’, ‘Abstract thought is largely, but not entirely, metaphorical’, ‘Metaphorical thought is unavoidable, ubiquitous, and mostly unconscious’, ‘We live our lives on the basis of inferences we derive via metaphor’.

Research by cognitive scientists into metaphor has continued[10] to confirm that metaphor is embedded in the way we think and perceive the world. One of the most exciting recent findings of cognitive science is that there might be just a few underlying concepts expressed through metaphorical speech, most notably space, time, force, agency and causation.[8]

In thinking about the relationship between science and language Steven Pinker in ‘The Stuff of Thought’ (2008) shows how embed the key scientific concepts of space, time, matter, and causality in everyday language. Nouns express matter as stuff and things extended along one or more dimensions. Verbs express causality as agents acting on something. Verb tenses express time as activities and events along a single dimension. Prepositions express space as places and objects in spatial relationships (on, under, to, from etc.). This language of intuitive physics may not agree with the findings of modern physics but, like all metaphor, it helps us to reason, quantify experience, and create a causal framework for events in a way that allows us to assign responsibility. Language is a toolbox that conveniently and immediately transfers life’s most obscure, abstract, and profound mysteries into a world that is factual, knowable, and willable.[14] What this means is that the logic of familiar concrete situations can be used as the logic for mapping and making inferences about more abstract things like time, quantity, state, change, action, cause, purpose, means, categories, and so on. What we do with metaphor is understand one mental domain in terms of another. Simile declares itself with the word ‘like’ but metaphor does not give itself away, it claims identity and, if we are not careful, we simply take it at face value, we take it for reality.

This is best understood through examples. While ‘it is raining cats and dogs’ is patently obvious, think for a moment about the way we treat the difficult concept of time. Time is one of the most difficult and abstract ideas we will encounter in life so, not surprisingly, the language of time is riddled with metaphor. We keep time, tell the time, and pass through time. Time is an object (‘Everything exists in time’); time is a moving object (‘Time bears all its sons away’); time is an object with variable speed (‘Time flies by more quickly every day’); time is stationary but we are moving (‘We are getting closer to Christmas’); time is moving but we are stationary (‘Time is passing by’); time is space (‘I was waiting a long time’, ‘It all happened in a short space of time’). ‘Time flies’ implies three metaphors, time as a bird, time as object, time as motion. Then there is the best of all, time as space, as in ‘It was a long time’.

Time is one of many examples: love is a journey; difficulty is an impediment to motion; purpose is a destination; the mind is a container (’empty-headed or full of ideas’); causes are forces; more is up, less is down; change is motion; the natural world is a machine; the mind is a computer – and so on.

You can see here how metaphor is being used as a tool for thinking about something obscure. This can be extremely useful in any creative process but we need to be aware of what language is doing. Time is not moving, it is not space, and it is probably not an object. Perhaps all this metaphor makes for colourful general communication but it does not always help us to think scientifically.

We need to be careful. Understanding X in terms of Y is not all bad, even though ‘the map is not the territory’. Considerable thought has been given to metaphor in science: metaphor is creative, thought-provoking and direct, it establishes likenesses and new meaning for difficult concepts so it is a verbal and sometimes visual aid to understanding – it is vivid, compact, and expressive. We need internal mental pictures to grasp new phenomena so metaphor is an invaluable tool for scientific communicators and a necessary heuristic, a way of explaining technical aspects of a subject to those who are less well informed. All this can lead science in directions that result in breakthroughs.

What are some popular scientific metaphors? Well, we think of Rutherford’s atom-as-a-solar-system and the way electricity flows like water through wire. But perhaps the greatest metaphor ever harnessed by science has been Descartes’s ‘nature as machine’, like a clock, and the path of explanation proceeding by analysis from the simple to the complex. On the one hand it taught us to seek answers by looking carefully at the wondrous interconnection of parts. But it also needed a ‘designer’ and it made us introspect ‘downwards’ in ever more detail with a reductionism that forgot how to look ‘up’ as Aristotle had suggested. Sometimes the universe, and especially planet Earth, has been compared to a cosmic organism (Gaia). Today’s great metaphor is the computer, a universe or mind that is driven, not by a designer, but by universal software, the ‘governing’ laws of physics and natural ‘selection’. This is a world, not of billiard balls, but complex systems.

I dont think we need to agonise too much about metaphor in science, worrying about all its advantages and disadvantages. We treat it as we would anything else in science: when it is useful, a good way of understanding and explaining something, then we keep it. If it becomes misleading or tired, or we find something that does a better job, then we replace it … but awareness of its dangers is a good start.

I have my own axe to grind and it relates to the metaphor still widely used by philosophers and biologists who speak about living organisms and their world as consisting of hierarchical levels of organisation, ranked by, say, molecules, cells, tissues, organs, organisms, and then maybe populations and ecosystems. To what extent is this just a convenient way of explaining things and to what extent is it the way the world really is? I think we can improve on this metaphor.

Finally, just to get into the metaphorical groove, think about the way we apply direction – ‘up’ and ‘down’ – to so many aspects of our lives.

Here is a comparative list of metaphors associated with ‘up’ and ‘down’:

Up – more (numbers have risen), increasing (prices are going up; high stakes), complex (what a mix-up, high-tec), happy (things are looking up), good (straight up), synthetic (lets built it up)

Down – less (numbers are going down), decreasing (prices are going down; bottom dollar), simple (low-maintenance, low-brow), sad (I’m feeling low), bad (drop dead), small (we’re down to the last), analytic (no, lets reduce it, or break it down)

The ‘up/down’ metaphor is also illustrated with the social metaphor of ‘high’ and ‘low’.

High – Look up to, Talk up an idea, Head, top (top cat), heaven, God up in Heaven, glass ceiling for women, upstairs

Low – Look down on, Talk down an idea, Body, bottom (dog’s body), hell, Devil down in Hell, basement, downstairs

The point here is to become attuned to the use of metaphor because it is pervasive in both everyday and scientific language. For example, I respect the efforts of scientists and what they are trying to achieve with science. Describing science metaphorically as a ‘narrative’ to me sounds insulting. Science tries to meticulously and accurately explain the world. No matter how inadequately it does this – it is doing far more than simply telling a good story.

There is not the space to go into this fascinating topic further but if you are a scientist then some background reading on the cognitive science of this topic could change your outlook on the world. Suffice it to say that in unwittingly accepting metaphors we can make life difficult for ourselves, and in handing out metaphors to other people we can be influencing both their minds and behaviour … so they need to be the right metaphors.

Consider the following:

Biological metaphors

Science faces a dilemma in communicating its relationship to nature. On the one hand science prides itself in its objectivity and detachment (fact and value, self and non-self) while, on the other, it wishes to re-connect people with the natural world by pointing out that not only are we evolutionarily connected to the community of life but we are also embedded in the environment. Certainly for anyone who feels empathy for the beauty and wonder of nature its objectification and respect only when viewed in instrumental terms is sad.

Mother nature

Is nature a mother, our surrounding landscape or a resource – or perhaps something that, after we have treated it as the source of our consumption, will inevitably hit back by consuming us? Obvious value-adding occurs for example in the expressions ‘invasive plant’, ‘clean energy’ and ‘soft science’.

Biology as economics

When we speak of ‘Ecosystem Services’ and ‘natural capital’ is this facilitating communication through economic metaphors that everyone understands or is it an unseemly deference to the world of economics? Are all actions transactions?

Does it work and does it help?

DNA Barcoding

Two examples can illustrate this point. Firstly, when scientists speak of the ‘DNA barcoding of nature’ do you think this a clever metaphor that engages people with their familiar world of retail shopping or does it endorse the characterisation of nature as a landscape of merchandise – of organisms as products on a supermarket shelf and DNA a product identification number that can be subsumed under modern technology?[19]

Invasive organisms

One of the best-known and most widely discussed metaphors in biology is that of invasive organisms which are sometimes discussed and associated with a rich lexicon of other militaristic terms: we have a ‘war on weeds’. Is this inflammatory fear-mongering language encouraging irrational xenophobia? After all, invaders must be repelled quickly and efficiently, preferably by extermination and killing. Isn’t this a term that pre-judges new plant arrivals? The idea of invaders also invokes associations of inviolable boundaries and territories and a mind-set of natives and exotics, goodies and baddies. Can this be considered yet another example of alarmist hyperbole – the ‘apocalyptic and fear-laden imagery’ so often associated with a narrative of impending disaster and presaged by environmental science?[12]

Or is this a highly effective way of drawing public and scientific attention (not to mention research funding) to one of the greatest threats to biodiversity on the planet – a way of evoking some response from politicians and the general public when inaction is the norm – where extensive objective evidence and scientific information is met with indifference? Or does such talk de-sensitize and therefore result in apathy and denial and alienation of scientist and citizen? Does it have an adverse effect on children by making them fearful of the natural world and a paralysis of pessimism about the future?

As scientists we need to be aware of value-laden metaphors and the way that metaphor unites fact and value, and can confuse and mislead with its multiple meanings (polysemy). In creating metaphors of our own we need to be fully aware of their power and take time to engage in critical metaphor analysis to ensure that our metaphors nurture sustainability.[13]

Plants & people

The metaphor (euphemism, symbolism) of common language provides a kind of subliminal appraisal of human physical and personality attributes, a kind of folk psychology with possible universal application.[1] How do we use botanical metaphors (botanomorphism) to describe ourselves? Animal metaphors are everywhere but plant metaphors far fewer. Through an analysis of dictionaries attempting to remove reliance on context and culture it appears that fruits are more highly valued that vegetables in their use as descriptors of positive characteristics.

Here are just a few metaphorical words used in relation to plants: class, family, community, alien, invasive, food chain, keystone, and disturbance – but such a list can be greatly extended. [p. 5] Science communication and education both face the difficulty of passing on cold and unfamiliar objective facts in a way that engages through everyday familiar values.

Value & objectivity

Insofar as science is an attempt to remain objective and value-neutral, every scientist should be aware of the use of metaphor. Science and scientific language are full of ideas that assist us in understanding and controlling reality. a metaphor generally emphasises some aspects while obscuring others.

I was educated as a scientist with the assumption that science cannot comment on the world. Science simply describes the way the world is, not the way it ought to be. This issue is discussed elsewhere (Science & morality, morality & sustainability).

Scientists are encouraged to communicate in an engaging way and that generally means ‘colourful’ metaphorical language. The danger is that we are expected to communicate about the world ‘as it is’ so metaphor, which is ‘as if’ language, is precisely what we are trying to avoid … ‘see’ what I mean?

One aspect of the scientific endeavour of being objective, to be value-neutral, to seeing things ‘from the point of view of the universe’ (Henry Sidgwick), is to remove those characteristics of our language that are specifically human. We must resist our inclination to see the world in human terms. Making the world person-like is a form of metaphor that we call personification. Cultures around the world have personified nature but perhaps the best example of this is the way God is referred to as ‘He’. Freud wasted no time in pointing out the obvious appeal of a kind and loving but authoritative father-figure guiding us through the vicissitudes of life. Firm but fair.

The scientific value of objectivity is obvious and to be encouraged but there is a downside. Elsewhere I point out that natural selection has the character of agency albeit unconsciously so. To ascribe conscious human-like purpose to natural selection is clearly a mistake, but the close resemblance of natural selection (which operates in the world not in our minds) to conscious purpose has warranted the special term teleonomy. Darwin drew the analogy between artificial (human) selection and selection as it occurs in nature, being fully aware of this objective similarity and that, unlike rocks, living organisms have persisted because they survive and reproduce with modification. Again this is a fact in the world, not an interpretation added by our minds.

This and other examples indicate that there is a downside to objectification. In reality we share many characteristics with all living things: we can emphasise these similarities through empathy or we can isolate and detach ourselves from them by concentrating on our difference. As humans we are both purposive and passionate. Though objectivity has many advantages we do not want to deny our humanity altogether. Acknowledgement of our biological need to survive, reproduce and flourish must be a human given.

Scientific Communication – Epilogue

Metaphor runs deep into our psychology, beyond its use as a literary device, and it is the source of both scientific insight and confusion. We simply need to use it with care. We can avoid the covert aspect of metaphor by using more explicit analogies and similes. And heaven-knows, science can be dry. Never forget some humour.

I hope I have now turned you into a logothete (one who accounts, calculates, or ratiocinates, or who ‘sets the word’). The exact origin of the word ‘logothete’ is uncertain, but it referred to some kind of state official. Around the sixth century CE logothetes gained in prominence and power as revenue-gatherers who were allowed to keep a twelfth of the sums they would gather for the Emperor’s treasury, and some of them amassed considerable fortunes. So, if you become a good logothete then you’ll never have to worry about your research grant again.

I’ll leave you with a hierogram (a sacred message), this one referring to both science and its communicators. It includes the neologism ‘synectics’ a word coined in the 1960s but derived from the ancient Greek. ‘It is not ‘all in the mind’ but a matter of synectics – the creative process of group problem-solving.’

Key words & expressions

Acronym, Acrostic, Abbreviation, Adage, Aide Memoire, Alliteration, Amnesia, Anadiplosis, Ananym, Analogy, Anamnesis, Anaphor, Anastrophe, Anathema, Anecdote, Anthropomorphism, Antithesis, Antonym, Aphorism, Apologetics, Apophasis, Aporia, Aposiopesis, Apothegm, Aptronym, Archetype, Assonance, Asyndeton, Autophasia, Backhanded compliment, Backronym, Bon mot, Bowdlerise, Bullshit, Buzzword, Caesura, Cacophemism, Catachresis, Catch Phrase, Catch-22, Catharsis, Charactonym, Chiasmus, Chinglish, Circumlocution, Classic style, Cliché, Cockney slang, Cognomen, Consonance, Corporatese, Dialectic, Diasyrmus, Discourse, Distinctio, Double Bind, Double Entendre, Doublespeek, Dysphemism, Eironeia, Enantiosis, Encomium, Ennoia, Epanalepsis, Epideixis, Epigram, Epitaph, Epithet, Epitrope, Eponym, Equivocation, Erotesis, Ethos, Eulogy, Euphemism, Fable, Figure of speech, Figurative, Franglais, Freudian slip, Fuck patois, Gainsay, Gibberish, Gobbledygook, Heterogram, Heteronym, Hierogram, Hobson’s Choice, Holorime, Homograph, Homophone, Homonym, Hyperbole, Hypocatastasis, Hypostasis, Hypozeuxis, Idiom, Innuendo, Isogram, Jargon, Juxtaposition, Legalese, Literary device, Litotes, Logology, Logos, Logothete, Malapropism, Maxim, Metaconcept, Metadiscourse, Metaphor, Metathesis, Metonym, Mispronunciation, Mnemonic, Mondagreen, Moniker, Mot juste, Multinym, Mumbo-jumbo, Narrative, Neologism, Onomatopoeia, Orator, Overstatement, Oxymoron, Palindrome, Panegyric, Pangram, Parable, Paralipsis, Parody, Paronomasia, Parrhesia, Pathetic Fallacy, Pathos, Patois, Personification, Platitude, Pleonasm, Polemic, Polysemy, Polysyndeton, Portmanteau, Pregnant pause, Procatalepsis, Prosaic, Prosody, Protasis, Proverb, Pseudonym, Psychobabble, Pun, Quadrivium, Recreational linguistics, Redundancy, Rhetoric, Rhetorical Flourish, Rhetorical Trope, Rhetorical Question, Rhyme, Risqué, Sarcasm, Satire, Semantics, Simile, Slang, So-to-say, Sobriquet, Solecism, Sophist, Spoonerism, Syllepsis, Synchysis, Synecdoche, Synectics, Synoeciosis, Synonym, Tautology, Tautonym, Tautophrase, Technobabble, Texting, The curse of knowledge, Tongue-twister, Trivium, Trope, Truism, Understatement, Weasel Words, Word Salad, Wordsmith, Zeugma.

—

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

© Roger Spencer 19 June 2018

Is that all there is?

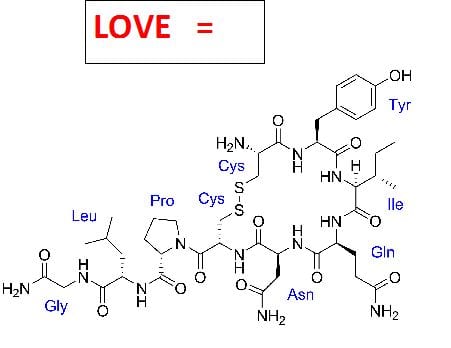

Communicating the scientific image in terms of the manifest image. Oxytocin is the ‘cuddle’ hormone – is that what love is?

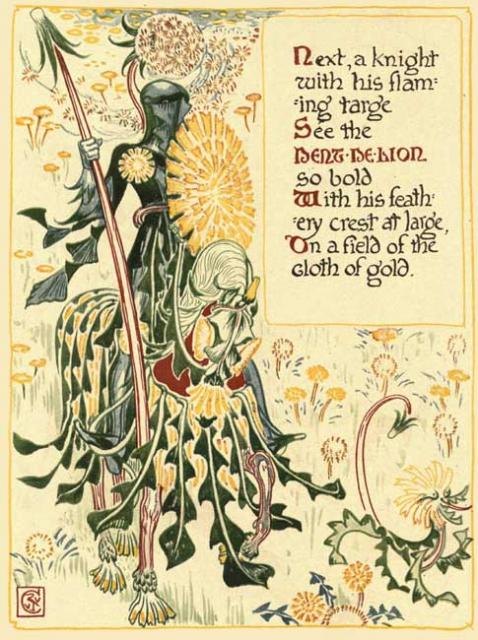

Sir Dent-de-Lion

A dandelion flower illustrated ‘as if’ it were a knight – an example of a pictorial metaphor

1899 Walter Crane (1845-1915)

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Fae, Accessed 20 Oct. 2015