The Silk Road

The Silk Road

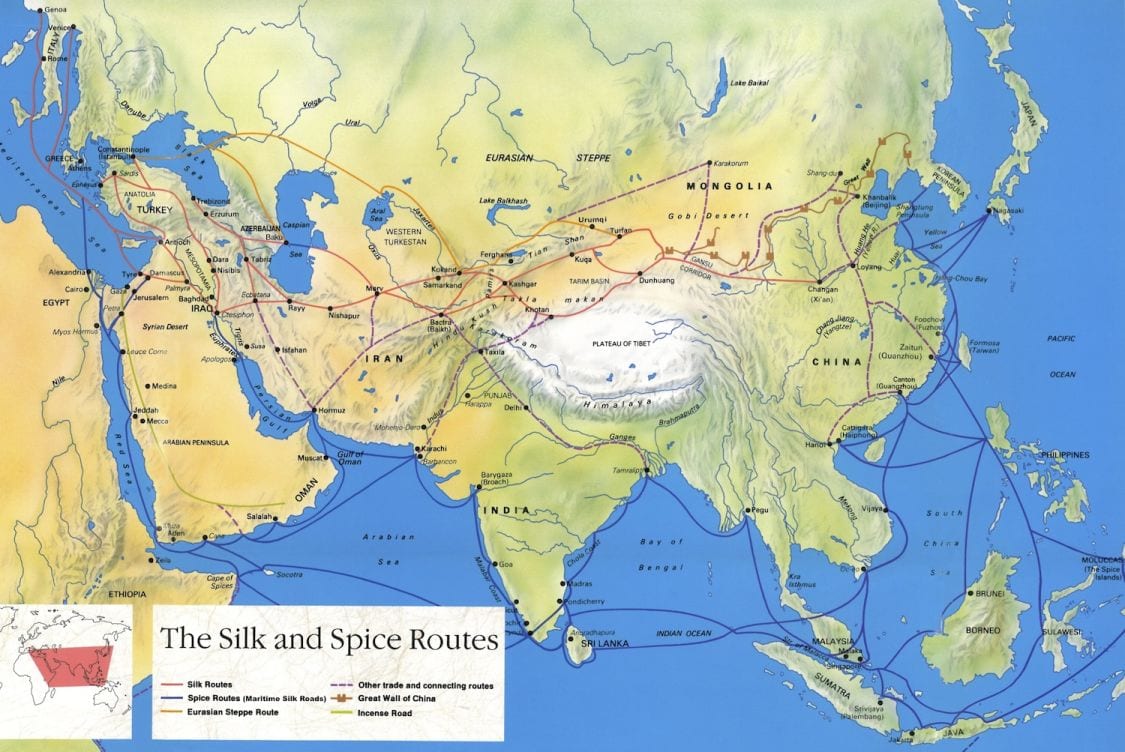

Red indicates land routes, blue indicated water routes.

The Silk Road and Indian Ocean Trade routes were major arteries of globalization in antiquity.

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Ancient trade routes

Trade routes have been the arteries of civilizations that have shaped our modern world as merchants, warriors and pilgrims carried new ideas, ideologies, religions, products and even pests and diseases around the world.

Many of the trade routes familiar to us today – both those in existence, and those mentioned in historical literature – were the remains of routes that had existed for many years before. So, for example, in Australia Aboriginal Dreaming Trails criss-crossed the country millennia before they were converted by European settlers into stock routes and then into modern highways. We know from archaeological evidence that in Europe there was a keen Neolithic trade in not only shells, precious stones and obsidian but also spices.

Silk Road

The great ancient Mediterranean civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome sourced the spices of the East, especially nutmeg and cloves, via the most extensive trade route of the day, the 6,500 km-long Silk Road whose arms reached into China, India, Persia, Mesopotamia and Egypt. In the first century CE the Old World was interconnected by trade between the Roman empire in Europe, the Parthian Empire in Mesopotamia, the Kushan Empire in northern India, and the Han dynasty in China. Gathering momentum in the Han Dynasty (207-220 CE) the road was at its height during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) and continuing into the Middle Ages.

The Silk Road is mentioned by Virgil and Caesar’s Rome purchased huge volumes of silk- although the name ‘Silk Road’ was not widely used until the 19th century, coined by Richthoven in 1877.

European trade in spices, sourced from India and the Far East, dates back to antiquity, to at least the Neolithic c. 1,000 BCE. Among these early traded spices obtainable from the East, many from unknown sources, were: cardamom, ginger, turmeric, cloves, sandalwood, nutmeg, mace, cassia, cinnamon, and pepper. Musk, rhubarb and licorice were also traded along this route.[16] Cardamon and tumeric, probably from India, were grown in Mesopotamia of the 8th-7th centuries BCE.

Even in antiquity cloves and nutmeg were traded along the Spice route that included East Africa, India, and China, Arab camel trains taking a path to the Mediterranean across the Egyptian, Arabian, and Central Asia deserts and steppe, changing hands many times, the cost increasing with each transaction. From the 7th century it was the Muslim traders that controlled this spice market. Archaeologists have found cloves in a pantry jar excavated in Terqa, Syria dating to around 1721 BCE[8] suggesting an extremely early trading route from the distant Spice Islands. Chinese silk occurs in Egypt from at least 1070 BCE.

Silk production in China can be dated to around 2700 BCE and was later associated with the imperial court, production methods always being a well-kept secret from outsiders. Complete silk garmens have been recovered from tombs of the Hubei province dating from the 4th to 3rd centuries BCE. By the time of the Han Dynasty (207-220 CE) it became a major export, transported in quantity along the length of the Silk Road as far away as Egypt and northern Mongolia. The Great Wall offered protection for the trade at the Chinese end. The Silk Road was an artery of trade products that linked Europe, Arabia, Greece, India, Persia, Rome, and the Horn of Africa, with traders who were Arab, Armenian, Bactrian, Chinese, Greek, Indian, Persian, Roman, Somali, Sogdian, Syrian, and Turkish. However the secret of production spread first to India and Japan, then the Persian Empire and the West in about the 6th century CE, the later Byzantine Church taking special pride in silk garments and hangings.

Goods

The name ‘Silk Road’ can be misleading as many more items were traded between East and West. Silk, though important, was just one major product of trade that also included spices, grain, vegetables, fruit, woodwork, textiles, animal hides, tools, metal work, religious artefacts, art work, and precious stones.Paper, gunpowder and musical instruments passed from East to West.

India – ancient Land of Spices

India’s reputation as a land of spices had attracted ancient Babylonians, Assyrians and Egyptians to the Malabar Coast as early as c. 2000-3000 BCE. Later there was trade with Arabs and Phoenicians. India was known as the ‘Land of Spices’ not only because of its wealth of native pepper and the cinnamon that came from nearby Ceylon, but also because it was an international trading centre. India traded not only with the West but welcomed traders from Asia and the Far East. Many spices now popular and widely grown in the tropics were first traded from the southwest coastal region of Kerala in India with records dating back to 3000 BCE, this coastal region was a commercial hub for the exchange of spices and many other goods, by both land and sea.[6]

Bronze Age civilizations

Ancient Egyptian papyri dating from 1555 BCE provide us with a founding list of Mediterranean herbs and spices: coriander, cumin, fennel, garlic, juniper, and thyme as health promoting spices[4] Records from that time also note that labourers who constructed the Great Pyramid of Cheops consumed onion and garlic as a means to promote health. Queen Hatshepsut (1508–1458 BCE) the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth dynasty sent maritime expeditions to Punt (today’s Ethiopia and Somalia) and they returned with 31 live myrrh trees stored with their roots in baskets.[7]

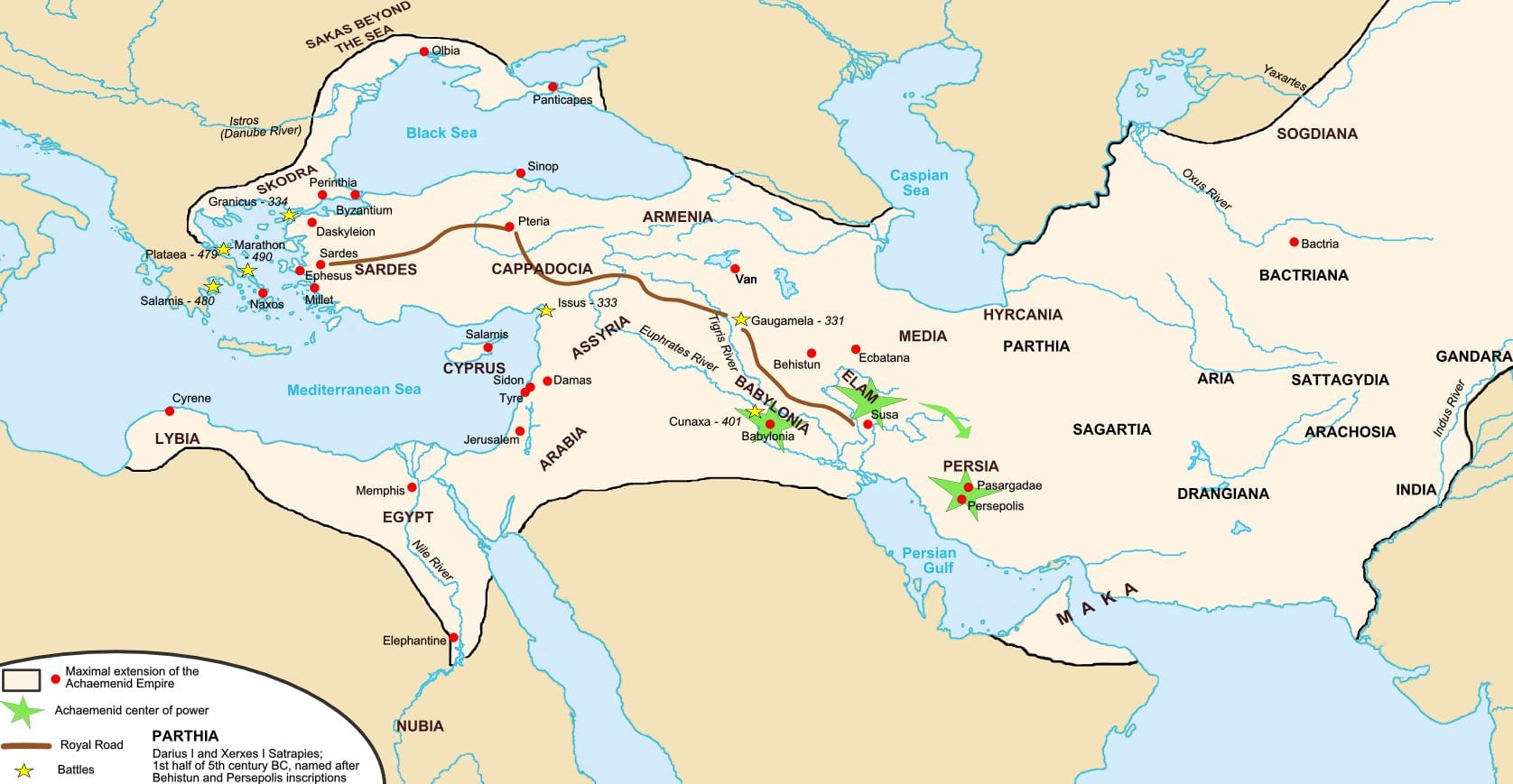

Persian Royal Road of the Achaemenid empire

c. 350 BCE – Road indicated by dark Brown line

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Fabienkhan – Accessed 10 Nov. 2015

Persia’s Royal Road

The Persian civilization arose in the 6th century BCE from a region of what is today’s southern Iran, expanding to the shored of the Aegean and Egypt in the West and the Himalayas in the East. This was a civilization that enjoyed trade, luxury, the tolerance of minorities and a strong military. Opulent cities were established in Babylon, Persepolis, Pasagardae, and Susa. Of the early civilizations Herodotus tells us of the impressive Persian Royal Road, a carefully maintained artery of the Achaemenid empire (c. 500-330 BCE) extending for nearly 3000 km from the city of Susa on the Tigris in the East to coastal Smyrna (modern Izmir in Turkey) in the West.

Travelling the full length would normally take about three months but by using fresh horses from the regular staging posts riders could complete the journey in nine days. No doubt this impressive road served as a model for later engineering feats like the Roman roads that would criss-cross Europe.

Persian merchants extended trade from India into the Persian Gulf, along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers to the camel trains that would take spices and other goods on to the Silk Road city of Palmyra, linking to traffic from China, and through to coastal Tyre and Antioch. Palmyran wealth was displayed when its queen Zenobia briefly and unsuccessfully attempted to excise the city from Roman control.

Persians were renowned for their love of commerce and luxurious indulgence, their and tolerance of minorities and religious difference, and the magnificent architecture displayed in the major cities of Persepolis, Pasagarde, and Babylon. Trade included luxury items, often sourced from special locations in the Persian empire and beyond: ivory from India, turquoise from Khwarezm, lapis lazuli and cinnabar from Sogdiana, gold from Bactria, silver from Egypt and among the plant material ebony from Egypt and Cedar from Lebanon.[2]

Greco-Roman trade

Mediterranean herbs were first supplemented by major spices from the Far East at the time of the Greco-Roman empires beginning in about 600 CE,[1] their use widening until by about 1300 CE they were well known throughout Europe.[2] Cinnamon, ginger, ‘cassia’ and pepper were all used by the Romans and Greeks.

Hellenistic period

Greek trade with India is described by Eudoxos (408–355 BCE) a Greek scholar who studied in Egypt at Heliopolis. Macedonian Alexander the Great’s military campaign against the Persians extended Greek influence eastwards and in 329 BCE he reached his eastern limit in a march down the Indus River and the region adjacent to the modern Chinese province of Xinjiang. At the eastern extreme of his march Alexander founded a Greek settlement, Alexandria Eschate (site of today’s city of Khujand), in what is today the southwestern part of the Fergana Valley which is in Tajikistan.

Greek culture would remain a powerful influence in Central Asia for about three centuries resulting in a Hellenization of not only the native peoples but, to a lesser degree, Persians, Indians and Chinese. Greek gods and Homeric works were introduced to both Persians and Indians a consequence of which might be the echoing of themes in the literary works of these countries.

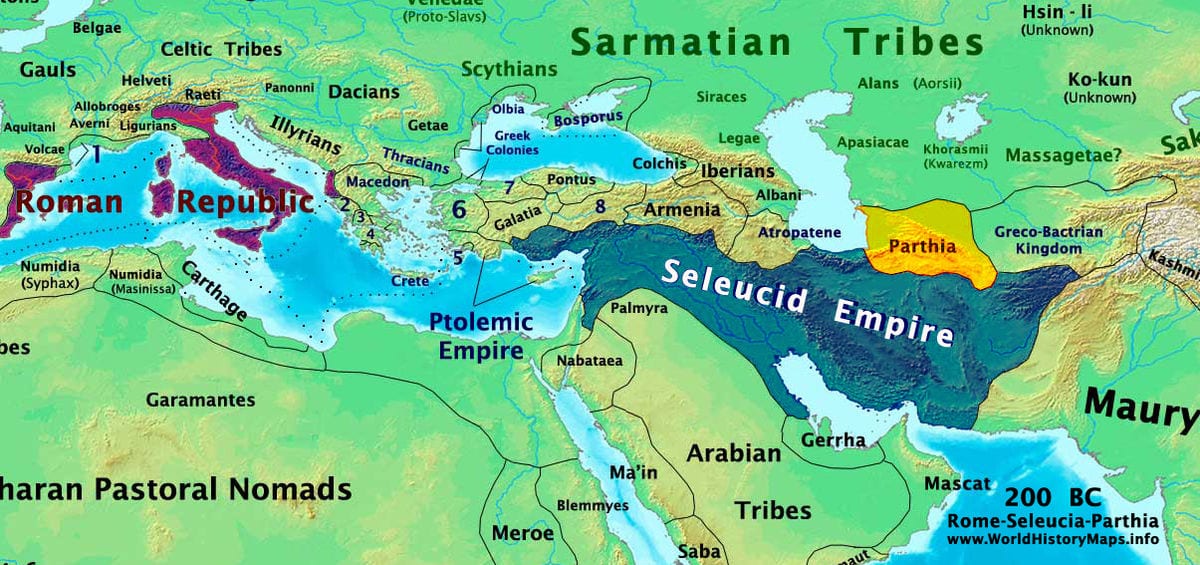

Following Alexander’s death the Greek empire he had created through military conquest was divided between his generals. The eastern region fell to Seleucus who created a dynasty lasting from 312 BCE to 63 BCE. At the height of his power Seleucus I commanded a vast Seleucid Empire in its west consisting of central Anatolia, Persia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and in the east today’s Kuwait, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and northwest parts of India.

Mixed cultural influences are especially notable during the from 250-125 BCE in Bactria (todays Afghanistan, Tajikstan, and Pakistan) but also an Indo-Greek fusion lasting from about 180 BCE-10 CE in northern Afghanistan and Afghanistan.

Greco-Bactrian Kinging Euthydemus I (c. 260-200/195 BCE) successfully defended Sogdiana (which included parts of todays Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) an important historical province of the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered by Alexander, its main city being Samarkand. However the area was recaptured by the nomadic Scythians[1] and Yuezhis in 150 BCE. However it is possible, as suggested by Strabo, that it was in about 200 BCE that the first official contact was made between the West and China (called Seres by historian Strabo). (Strabo XI.XI.I”. see Perseus).

The Greek Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. 50 CE) mentions that a Greek navigator Hippalus had discovered an oceanic route from Arabia to India harnessing the south-west monsoon wind which blew from June to October taking him to India, allowing a short rest before returning to Arabia with the north-east monsoon which blew from December to March. With this knowledge a vigorous trade opened up between the Red Sea coast and India to be later closed down as Muslims overran Alexandria in 641 CE and Venice was given a monopoly of European trade with the Arabs.

Trading around the Arabian peninsula

Periplus Maris Erythraei

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Roman Empire

Roman trade with India was, at first, a long overland journey by caravan through Persia (Iran) and Anatolia (Turkey) but from at least 305-30 BCE Greco-Egyptian Ptolemies traded by sea and the time of Ptolemaic Egypt (c. 330-30 BCE) goods were also transported between the Red Sea and the trading ports of western India across the Indian Ocean. From the head of the Red Sea it was a relatively short land journey to the Mediterranean and the vibrant trading port of Alexandria (with a population approaching half a million[14]which was a pre-Christian hub for the camel trains to Arabia, Egypt, and Levant and ships to the Mediterranean ports of the Greco-Roman world. Arab traders controlling trade through the Red Sea never divulged their sources in the Far East. Pliny the Elder in 100 CE observed that Roman gold was flowing eastwards paying heavily for the pepper so beloved of the Romans. Cloves were available in China by 200 BCE[4] reaching the Mediterranean by 300-400 CE[5] to become a familiar luxury throughout Europe by 800 CE. Merchants from the Roma Empire took care to travel north through the Caucasus and Caspian Sea region, avoiding the aggressive Parthians.

Greco-Roman Silk Road trade

Roman trade along the Central Asian Silk Road was interrupted by raids from the Parthians.[3] Parthians dominated trade on the Silk Road for many years, especially the diaphanous silk so much in demand by Roman women. This was regarded by some as a decadent luxuriant excess placing unreasonable sums of money in the hands of traders. Pliny remarked that India, China and the Arabian Peninsula ‘… take from our empire 100 million sesterces a year – such is the sum that our luxuries and women cost us …’[5] Silk became so popular it made up more than 10% of the annual Roman budget (F. p. 18). Trade was in both coin and goods with trading towns growing and prospering.

East of Persia the Kushan tribe began minting coins modelled on those of Rome transferring wealth to oasis towns. The Kushan empire of the first century CE included N India and C Asia and this was a region through which Buddhism would spread. In the 200s Sasanian influence would spread into Kushan territories.

Sogdians

Sogdians were travelling merchants and middle-men of C Asia who became Buddhists. The former kingdom of Sogdiana later formed part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and Sasanian Empire, Sogdian states centered on the major trading city and capital Samarkand (now Uzbek). Sogdian territory corresponds to the modern provinces of Samarkand and Bokhara in modern Uzbekistan as well as the Sughd province of modern Tajikistan.[5] By the 4th century CE Indian-originating Buddhism was widespread in NW China although it had also filtered into the West in Persia. All this resulted in ‘faith wars’ that dogged the first 400 years CE.

Chinese general Ban Chao led several expeditions as far as the Caspian Sea at the end of the first century CE and dealings with Persia and included frankincense and myrrh but there was little contact between China and Rome from either direction. With Persia at the heart of the known world Rome sent out Trajan in 113 who quickly took major cities only to be beaten back and occupied with other uprisings although it was the eastern front that always caught the attention of Rome. In 220 CE highly organized Sasanians heralded a new Persian era of development in C Asia, Iranian plateau, Mesopotamia, and the Near East as Roman power began to wane. Emperor Diocletion determined to extract maximum taxes from the populace and prices were established for staple goods as well as luxury items like sesame, cumin, horseradish, and cinnamon. Focus was emphasised by the establishment of New Rome (soon Constantinople) at the boundary of West and East.

Parthia c. 200 BCE would expand to encompass Seleucid territory to form a Parthian Empire

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Talessman – Accessed 19 Nov. 2015

The Incense Route & Nabateans

Trade in the period of about the 7th century BCE to the 2nd century CE between Southern Arabia, the Horn of Africa (today’s Ethiopia and Somalia), and the Mediterranean – Arabia to Damascus – is sometimes referred to as the Incense Route mostly for Arabian frankincense and myrrh but including, from India, spices, silk and textiles, precious stones, pearls, and ebony, and from the Horn of Africa rare woods, animal skins, feathers, and gold. Greco-Roman trade in about 700 BCE-200 CE linked with North Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Arabian Peninsula where Frankincense (the aromatic resin of four species in the genus Boswellia) was obtained as well as Myrrh (an aromatic resin from species of Commiphora) traded along what is known as the ‘Incense Route’.

The Nabateans were skilled traders originating from Saudi Arabia or Mesopotamia who moved into Jordan and eastern Arabia. Skilled in hydraulic engineering they built cisterns and water basins, worshipped the Sun, and usedg frankincense to connect with the spiritual world. The civilization reached its height in the second century of the Common Era when they controlled the trade routes that passed through Jordan and Arabia on the way to Gaza, Alexandria, and Damascus. Persian king Darius traded with the Nabateans as did Alexandria’s Ptolemy. Gradually they monopolized this trade developing their own army and building their capital at Petra, hewn out of the sandstane in a narrow valley. Other Nabatean cities included Avrat, Shivta, Haluza, and Manshit. Now a famous tourist attraction Petra still has its magnificent ‘treasury’ and architecture that has Greek, Syrian and Nabatean elements. Their trading network, which centred on a series of about 65 oases that they controlled, where agriculture was intensively practiced in limited areas.

The Nabatean Empire eventually succumbed to the Roman Empire of Augustus and Tiberius whose economy was becoming depleted through vast expenditures on luxury goods, most notably silk, frankincense and myrrh. Attention would then turn to Palmyra.

Lust for spices is amply demonstrated by Alaric the Goth who, to call off the Visigoth siege of Rome in 408 CE, demanded a bounty of gold, silver and 3000 pounds of pepper.

Greco-Roman maritime trade

For a brief period historian Strabo reports that Romans avoided the Arab intermediaries when, in the reign of Augustus from about 63 BCE to 24 CE, a fleet of about 120 Roman ships would pass down the Red Sea to make an annual round-trip to India, but this trade returned to Arab hands when Alexandria fell with the Roman empire.[3]

Alexandria enjoyed a golden age under the dynastic rule of the Ptolemys who, following Alexander’s conquest, ruled for 275 years from 305-30 BCE through the Hellenistic period up to the Roman conquest after which Rome inherited the old Greek trade routes. This was the last great Egyptian dynasty following the pharoahs ending with the demise of Egyptian Cleopatra as a result of her fatal dalliance with Roman General Marc Antony which resulted in a Roman takeover of trade following the Battle of Actium in 30 BCE. Rome now controlled the massive grain harvests of the Nile Valley and the Roman economy boomed. Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE – 14 CE) claimed that he inherited Rome as a city of brick and converted it to a city of marble.[10] Cicero reports the sending of tax assessors to Judaea for a census and the observation of a land of luxury and plenty prompting an assessment of Roman land and sea trade around the Persian Gulf. Within a few years 120 Roman ships were sailing for India every year.[11] Villages on these trade routes grew into thriving towns and cities and Roman monuments were erected everywhere. Romans admired the silk from China which allowed the ‘Roman lady to shimmer in public’ (Pliny NH 6.20) and a imports made up as much as 10% of the Roman budget.[13] Alexandria, as a busy cosmopolitan trading port, the docks buzzing with Phoenicians from the Levant, Greeks, Egyptians, and the black Nubians of today’s Sudan. Trade passing betwen the Mediterranean and India passed from Alexandria, down the Nile to Aswan before being taken by camel train to the Red Sea port Berenice Troglodytica (trade hub between India, Arabia, and Upper Egypt) sailing to the coastal port of Aden before passing along the Gulf of Aden to cross the Arabian Sea sailing southwards down India into the Indian Ocean before setting out for Malabar on India’s south-western coast.

Both eastern and western Indian ports served as emporia for goods from eastern and south-eastern Asia. According to The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. 50 CE), the only eye-witness account of the spice trade in the classical era between Berenice in Arabia to the Indus River, Malabar coast, Sri Lanka, Coromandel coast and Ganges River in the Bay of Bengal. Greeks enjoyed perfumed oils as did the Romans whose opulence drew heavily on imports of pepper and cinnamon. Spices sweetened the aroma of funerary pyres.

By this time in history East was connected to West by societies that were administratively skilled, competitive, and efficient. Goods and coins passed through China, Central Asia, India, Persia, Arabia, and, once in the Mediterranean, dispersed throughout Europe and as far west as the British Isles. Global connectivity like this would shortly break down and not return until broken land routes were supplemented by the sea routes ploughed during the Age of Discovery.

By 410 CE the Roman Empire had become fragmented, literacy was on the wane, and stone buildings no longer the order of the day. In about 540 CE bubonic plague spread along trade routes to both East and West, bringing economic depression. However, in the 5th century CE a Roman cookbook titled The Excerpts of Vinidarius lists more than 50 herbs, spices and plant extracts that ‘… should be in the house in order that nothing is lacking in seasoning‘.[17]

The world of learning and commerce would now pass to Arab and Muslim as, from 600 Persia spread its influence with Turks playing an increasing role. In 619 the mainstay of the Roman agararian economy, Alexandria, fell. In 614 Jerusalem fell. Islamic influence spread rapidly in the 7th century resulting in its own trade networks and wealth, much invested in Syria and the cities of Jerash, Scythopolis, and Palmyra but mainly to Baghdad which for several centuries would become the centre of the Islamic world and the richest and most populous city in the world made possible by the taxation of its vast and productive empire. In 527-564 CE Byzantine Emperor Justinian sent a successful secret mission to obtain silk worms from China the subsequent silk production in northern Greece (Thrace) becoming a European monopoly.

Indian trade

Carried across land and sea from Asia the spices of the Far East arrived in the West via India. India was a half-way house between East and West and, along with the Axum Empire of northern Ethiopia and Eritraea fl. 100– CE which bounded the Red Sea, controlled the sea lanes into the Red Sea at this time although Roman merchants had learned how to take advantage of the seasonal monsoon winds. The Grand Trunk Road running across northern India was especially active in the Hellenistic period but probably dates back several millennia.

In the Indian segment of the Silk Road there are the c. 30 rock-cut Buddhist Ajanta Caves dating from the 2nd century BCE to about 480 CE with paintings and rock-cut sculptures that are outstanding examples of ancient Indian art and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. They are, in effect, ancient monasteries and probably a monsoon retreat for monks, as well as a stopping point for travelling merchants and pilgrims.

The Ajanta Caves They are recorded by medieval Chinese Buddhist travellers and the Mugha official of the Akbar era in the early 17th century. Enveloped in jungle they were rediscovered and recorded for the West in 1819 by British colonial officer Captain John Smith when hunting tigers.

By 500 CE the Indian centre of trade had moved to Sri Lanka which was on the preferred trade route of merchants from Burma, Java, Sumatra and Malaya. Indian traders working in south-east Asia brought with them the Hindu and Buddhist faiths. Sanskrit inscriptions dating to the 4th century have been found in Indonesia perhaps the most obvious evidence of this Indian influence today being the 8th century Borobodur temple in Java and the 12th century temples around Angkor Wat in Cambodia.[12]

The overland route from India to Europe was by camel and packhorse and it passed from India to Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, the Balkans and, finally, to Venice. The loyalty of the Veneti tribe to Rome had been rewarded with a gift of marshy lands where the tribe had prospered such that, by the 800s, a small township called Venice had emerged. By the early 1500s Venice had the largest merchant navy in Europe an it used a sophisticated banking system with branches in Europe’s main cities. Eastern influence was evident in the architecture, like the Doges palace. In the Middle Ages meat was salted and pepper was regarded as a culinary necessity for the well-to-do. Spices generated much of the wealth on display in Venice, driving the spice race that was launched from the Iberian Peninsula. Pepper served as a currency for the storage and exchange of wealth and it was a useful source of government tax revenue.

Arabic numerals though originating in India, had arrived in Europe with Arabic merchants.

Indian connections with SE Asia and the Far East were invaluable to Arab and Persian traders of the 7th to 8th centuries.

Muslim trade

Islam, from its beginnings, encouraged trade. There was a natural transition from the star-guided navigation of camel caravans across the waves of the desert to navigation on the seas. From local trade in frankincense and myrrh to international trade in spices. Prophet Muhammad (c. 570-632 CE) was born into a family of spice traders and his revelations comitted to the Qur’an rapidly united the Arab empire from Baghdad to Alexandria under the religion of Islam and Muslim control of the spice trade throughout Arabia, initially under the control of the Umayyad Dynasty in Damascus. With the passing of the caliphate to the Abbasid Dynasty in 750 the centre of the Muslim world passed from Damascus to Baghdad, much closer to the Persian Gulf and trade along the Tigris and Euphrates. (B. p. 29) At the mouth of the Red Sea the port of Aden was used by shipping from India carrying ambergris, camphor, musk, and sandalwood. Captains would pay a tribute to the Sultan of Yemen to use the Red Sea and this led to the fabulous riches that are recounted in the Tales of Sinbad the Sailor. As Islam spread across North Africa c. 650 CE both overland European caravans and Red Sea shipping trade was closed off except via Arab merchants from Arabia and Persia.

By the mid 7th century CE there was a take-over of sea routes and this continued into the Middle Ages. Tribes of south and west Arabia also gained control of land trade between South Arabia and the Mediterranean. Nabateans took control of the route crossing the Negev from Petra to Gaza. Petra, the Nabatean city carved out of rock, provided an oasis for caravans on a route that passed by sea from Arabian Jeddah (adjacent to Mecca) on the east coast of Red Sea north to Medina, inland to Jordanian Petra and then on to Gaza on Israel’s southern coast. Trade in the Red Sea passed from Bab-el-Mandeb at the southern mouth of the Red Sea to Berenike, built by Ptolemy II and from the 1st to 2nd century CE the trading hub for Arabia, Egypt, India and the Malabar coast.

When Alexandria was taken by Muslim forces in 641 CE direct trade with the Mediterranean ceased. As early as 671 Arab and Persian traders were operating in China and by the 8th century were trading with Canton (today’s Guangzhou). Here goods from the Moluccas would be loaded on the ships for the return trip – silk, camphor, porcelain, and spices, this trade coming to a halt when Guangzhou was destroyed by rebel forces in 878. At about the same time Buddhist traders had established a strong trading centre at Srivjaya (near Palembang) in South Sumatra where nutmeg and cloves from the Moluccas were passed on to merchants from China, Arabia, and India.

In the 13th century Arab vessels sailed from Basra at the head of the Persian Gulf trading their cargo on the way and using the monsoon winds to arrive in Canton (Guangzhou) six months later. Through the 15th century there was increasing European concern about Muslim control of trade to the East, about 80% of this being in Arab hands in 1400.[18] The merchants of Venice were dealing with about 500 tons of spice a year, mostly pepper.

Muslim control of trade continued in the high and late Medieval period through the Ottaman Turks. In the Middle Ages European trade was largely controlled by Venetian and Genoan merchants who dealt with the merchants of the Byzantine Empire. When the Ottoman Turks took Constantinople in 1453 the overland trade between Venice and the Arabs was finally closed off. There was just one possible way forward for Portugal and Spain, the maritime powers of the day … a sea route to the Indies. Ottoman Muslim rivals, the Mamluks, followed by increasing the duties on spices passing through Alexandria.

Muslim trade domination was a major incentive for European sea powers to find alternative sea routes for their business and as navigational skills and shipbuilding improved the Age of Discovery opened up sea lanes via the Cape of Good Hope and world trade was steadily taken over by European colonial powers.

The first records of cloves in China date to the third century BCE.(B. p. 22)

By the 16th and 17th centuries technological advance in Europe – the improved ship building and sophisticated navigation aids so important to the Age of Discovery, the increasingly effective weaponry – presented European powers with the opportunity to loosen the Muslim grip on trade in the East while, at the same time, introducing the orient to the ‘one true religion’.

Mediterranean trade

European merchants were also able to cash in on the fortunes to be made from spices, serving as middle-men in Silk Road trade that passed through Byzantium. Although trade was delivered to many ports it was, between about 700 and 1500 that the maritime republics of Italy, most notably Venice and Genoa, commandeered the trade passing to the Middle East – not only the lucrative spices and incense but also opium and other goods. Italy thus held a virtual monopoly on this trade until the rise of the Ottoman Empire and the fall of Constantinople that closed to Europeans the land-sea route to the east, the merchants of Venice amassing huge wealth together with considerable resentment.

Indonesia

At the Far Eastern nd of the trade route were the Austronesian sailors who were ancestors of Polynesians, Micronesians, Maoris, Malayans and Madagascans. They used outrigger canoes that carried cargoes of rice, taro, sugarcane, yams, breadfruit, and coconuts. Pliny noted how in his day these remarkable sailors traded cinnamon, the journey from their homeland to the coast of Africa and back taking about five years. However, their major trade occurred in India and included cloves and nutmeg as well as cinnamon also venturing along routes to the Mediterranean that included the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, as well as the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates Rivers, in the classical era c. 50 BCE to 96 CE usually distributed round the Mediterranean following accumulation on the docks of Alexandria. Pepper was a major commodity traded with India at this time.[9]

China

While Rome was marching east, Chinese of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) were pushing west through the Gansu corridor to today’s northwestern Xinjiang Province from which it was about 1000 km to the crossroad city of Dunhuange on the fringes of the Taklamakan Desert. Progress was hampered by raids from the northern Yuezhi and Xiongnu nomadic tribesmen who, like the Scythians, were skilled horsemen. They were also a source of prize horses. The Kushan Empire was a syncretic Empire formed by the Yuezhi a people occupying the arid grasslands of today’s Chinese provinces of Xinjiang and Gansu. The Yuezhi siezed Greco-Bactrian territories in the early 1st century and at its height King Kanishka the Great (127–163 CE) ruled over an area that included much of Afghanistan and today’s Peshawar and northern India – from Turfan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain. Turpan was a trading hub with numerous inns and brothels, a slave trade but mostly supplying vegetables, cotton and grapes, as China’s largest raisin-producing region. For many years China was prepared to pay for peace in goods but eventually lost patience and after about ten years intermittent struggle managed, in 119 BCE, to occupy the Gansu corridor marking what is possibly the time of east-west integration on the Silk Road.

General Ban Chao with tens of thousands of troops penetrated from the Great Wall as far as the Caspian Sea, even sending an envoy to Rome.

Silk is a textile made from the extremely fine thread produced by silk-worms, the caterpillers of the insect Bombyx mori as they spin cocoons while feeding off the leaves of Chinese Mulberry, Morus alba. In a China lacking coinage silk was a valuable commodity of exchange and this use expanded into the international markets.

In the 7th century especially there was contact between India and China through the medium of Buddhist monks leading to later Buddhist shrines in Bamiyan (Afghanistan), Mount Wutai (China), Angkor Watt (Cambodia) and Borobudur (Indonesia).

During the Tang dynasty (618-907) (as Byzantium thrived). A Tang monk, Xuan Zang, travelled the Silk Road to India and Afghanistan returning to Xian with Buddhist scrolls. the capital city of Chang An in about 700 CE also thrived under the rule of female Wu Zetien. It had a population of about 1 million citizens and it was linked to the Silk Road as a city of great wealth and luxury based on its trade to the Mediterranean and Japan. Wu was a concubine who rose to become political leader during the brief Zhou dynasty interlude of 684–705 CE. Here there was the largest ever known palace complex (178 acres) that included areas for archery and polo. At this time rice was stored in vast granaries and Buddhism and its temples were established across the land. The famous five-storey Buddhist Giant Wild Goose Pagoda built in 652 CE in Xi’an was destroyed by an earthquake and was rebuilt in 701-704. This was an era in which women gained political power only to be resisted by the subsequent Confucian hierarchy.

The Gwangzou Canal connected north and south and was built in the 600s. In 605 there were 5 million workers as the canal shipped corn and building materials.

Tang China controlled about 55% of the world’s GDP and was an outward-looking superpower like Rome had been in the West. Around 630 Christianity was introduced but conflict and persecution arose in relation to both Islam and Buddhism in a period of anarchy before the building of a new golden age with the Song Dynasty c. 960 prior to the European Renaissance and with Caiphong a major centre. Wood block publishing blossomed with moveable type arriving with the Tang Dynasty in 1040.

Marco Polo visited Hangzou c. 1200, then the finest city in the world before it was overrun by the Mongols in the 13th century.

Emperor Yong Liu moved the capital to Beijing, built on the old Mongol capital as, in the 1400s the economy flourished to become the largest in the world encompassing 150-250 million people, about one third of the world population. After the outward voyages of Zheng He China turned inward and the Great Wall was constructed.

Mongol empire

From 1206 to about 1360 the Mongol power of Ghengiz Khan and family extended beyond the Central Asian steppes into northern China forcing the Song Dynasty in 1227 to move to the southern trading port of Huangzhou and a new maritime trade and when this also fell in 1276 Kublai Khan ruled a trading route that extended 6000 km from China to the Black Sea.[15] Strung along the route were trading hubs that included, from West to East, Erzurum (Anatolia), Kazan (C Russia), Solkhat (Crimea), Astrakhan (Lower Volta), Tabriz (N Iran, Samarkand (Transoxiana), Karakprum (C Mongolia) Beijing (N China). This ended the Islamic hold on world trade.

For the West this period is familiar through the chronicles of Marco Polo who was respectfully entertained by Kublai Khan who was keenly interested in life, the Roman Catholic Church, and other aspects of life in the the West. In 1271 the three Polo brothers Nicolo, Mafeo and the 15-year-old Marco had travelled with the Venetian merchant fleet noting that for the merchants of Venice, Pisa, and Genoa it was Antioch (Ayas) that was the main Mediterranean point of access to inland routes.

Maritime trade

At the time of the Tang Dynasty China opened its doors, accepting foreigners and their trade while themselves sailing beyond India to become regular merchants along the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. During the Han Dynasty there was a long period of peace, a Pax Sinica, at the same time as the Pax Romana. This was later followed by a second Pax Sinica lasting from 589 to 907, mostly during the Tang Dynasty (618–907).

Morco Polo describes Chinese merchant ships of the late 13th century carrying up to 300 people and cargos of 120 tons. Built with four masts, double hulls, airtight compartments (bulkheads) allowing the ship to remain afloat of the hull was damages – ships of this quality were not built by Europeans for another 500-600 years.

The 14th century was a golden age of intellectual and social achievement during the Ming (light) dynasty after the defeat of the Mongols in 1368 when Nanjing was the capital and Hong Wu the most accomplished emperor.

By the 14th century Western visitors were also amazed by Chinese skills with porecelain and the use of paper money. By 1402 Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty decided to open a political dialogue with the world’s great nations hoping that in return for gifts and protection they would pay tribute to the Emperor. Nanjing shipyards on the Yangtze River produced hundreds of giant junks – military, trade, and provision. This Treasure Fleet was placed under the command of Admiral Zheng He who, rom 1405-1433 led seven expeditions, the sixth rounding the Cape of Good Hope into the Atlantic. To mobilise such extraordinary campaigns, some with fleets of several hundred ships, required logistical skills and technology far in advance of any other country in the world. Though such forces were capable of subduing other countries these voyages were peaceable and on the death of Emperor Yongle in 1424 was succeeded by his Confucian son Zhu Gaotzi China once again looked inwards, leaving the seas open to the European ships and ambitions that would change the world. This theme is taken up in the next article.

Trade routes to 1450

By 1450 there were major arterial maritime trade routes linking the world’s eastern and western hemispheres with India, and especially its west coast, acting as a central hub. Ships passed between the Indian Malabar coast and East Africa which, in the north accessed the Mediterranean through the Red Sea (with access to the Euphrates and Babylon) and Persian Gulf with land routes to Cairo, Alexandria and Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean cities of Acre, Tyre and Sidon which, in turn, linked to the Black Sea ports and Silk Road. Through the Middle Ages Mediterranean trade was mostly controlled by the merchants of Italian city-states Venice and Genoa.

Ancient Greek accounts refer to Malay-Indonesian traders in 100 CE sailing directly in outriggers from Indonesia to the island of Madagascar off Eastern Africa, modern DNA analysis indicating that the people of Madagascar are direct descendants of Indonesian traders from today’s Kalimantan. This journey is known as the Cinnamon Route although the traded cinnamon was not that of Sri Lanka but the cinnamon of the East Indies (Cinnamomum sp.) more often confusingly referred to as Cassia. The circumstantial evidence of yams, taro, bananas and Asian rice in West Africa in the first millennium CE suggest a possible early rounding of the Cape of Good Hope by these Indonesian sailors.

Trade between the Indonesian Archipelago (cloves, nutmeg, tree resins) and China (cloth, silk, rice) was mostly through the Malacca and Sunda Straits to the port of Guangzhou (Canton) and controlled largely by Chinese traders. Goods would then find their way north to the major western spice market at Chang’an (Xian) (city of the terracotta warriors) in the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). From this market the road trains would assemble before heading westwards across the steppes of Central Asia the hardy Bactrian (two-humped) camels loaded down with silk, furs, lacquer, jade, bronze and spices the return journey would be western gold, silver, amber, glass, woollens and linen. Caravans would only cover one segment of the entire road, the merchants coming from China, Central Asia, Persia, Armenia, and the Arab world. (B. p. 33)

Covering large distances overland made huge demands on energy so the traded goods that were most useful were not only of maximum value but both lightweight and durable. Silk came to dominate this trade, serving as a form of currency. At the time of the Han Chinese maritime trade passed goods inland to Vietnam an then on to India and its inland trade routes.

Trading hubs

Long treks through rocky, dry, and sandy landscapes were broken by brief stays in welcome cosmopolitan oases called caravanserai, often situated about a day’s journey apart and at crossroads. Here camels could be fed and watered, and spirits rejuvenated by socializing with other merchants within secure lodgings. There were many branches to the Silk Road and in inhospitable regions these were broken up by oasis settlements. These hubs on the Silk Road included Lanzhou, Anxi, Kashgar, Samarkand, Balkh, Merv, Hamadan, and Palmyra.[15]

Dunhuang

in northwestern Gansu Province of Western China which, during the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties was the primary hub of the Silk Road between ancient China and the rest of the world being at the intersection of the three arterial silk routes – north, central, south – and situated in a regional oasis with a Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan or “Singing-Sand Mountain” from the sound of the wind and sand. This was a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient Southern Silk Route and the main road leading from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and Southern Siberia. It was also at the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, to the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang’an (Xi’an) and Luoyang. It is also well known for the Mogao Caves carved by early Buddhist monks from the first century AD and also a site of pilgrimage for Christian, Jewish, and Manichaeans.

Ephesus

At its peak Ephesus, on the west coast of Turkey, was the third largest city in the Roman Empire and capital of Asia Minor renowned for its library, mosaics, baths, apartments and a theatre that held 30,000 people.

Kashgar

(Kashi) is a remote western oasis city in Xinjiang province of the Peoples’ Republic of China, adjacent to Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan and the Taklamakan desert. Variously under Chinese, Turkic, Mongol, and Tibetan imperial rule todays population of about a half million people are more Turkic than Chinese. As a historical trading post on the Silk Road it has linked China to the Middle East and Europe for over 2,000 years. The ancient trade was often between horses and silk which would also pass up a northern branch of the Silk Road to Kazakhstan. A Sunday grand bazaar and markets attract surrounding farmers to trade in livestock, fruit and vegetables and local products.

Lake Issyk-Kul

In the northern Tian Shan mountains in eastern Kyrgyzstan is the second largest saline lake after the Caspian Sea and a stopping point on the Silk Road. In 2007 a report claimed the discovery of a 2500-year-old advanced metropolis at the bottom of the Lake with walls walls, Scythian burial mounds and well-preserved artifacts, including bronze battleaxes, arrowheads, self-sharpening daggers, casting molds, and money. The lake is the possible source of the Black Death of c. 1330-1350 possibly spread by vermin-infested medieval merchants travelling between Europe and Asia.

Palmyra

Palmyra, the place of palms, is an ancient city dating back over 3000 years to the Neolithic as a watering place for caravans crossing the Syrian Desert situated between the Euphrates River and the Mediterranean trade ports of Antioch (Antakya, Turkey) and Tyre (Sôur, Lebanon). At its height in the 1st to 3rd century CE it was a thriving trading centre of the Roman Empire and province of Syria and described by Pliny who first used the name Palmyra. Before Roman occupation this was part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) founded by Seleucus I Nicator one of Alexander’s three generals who inherited segments of Alexander’s empire. Seleucus took Babylonia extending it to the Near East but at the height of Seleucid Dynasty this included central Anatolia, Persia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and eastern lands as far as northwest India. Today the area is dry and many of the few remaining structures, notably the Greco-Roman Temple of Bel, were destroyed in 2015 by the political extremist group ISIL.

Petra

was a trading city controlled by the Nabateans, Arab traders who had established oases on a trading route that connecting China, India, Egypt and Rome. At its height Petra had a population of about 30,000 people with a skillfully engineered water supply built between 50 BCE and 50 CE. Buildings were carved into the sheer sandstone rock faces in a deep and narrow ravine, the style eclectic but mostly Greco-Roman and individualistic style elegantly exemplified in its most famous building, the Treasury. Aramaic inscriptions were found in the many elaborately carved tombs. Among the goods traded were Frankincense and Myrrh, the luxury city was positioned on the famous Incense Route from Gaza to Saudi Arabia and described by Roman chronicler Pliny as the richest nation on earth. Dangerously situated the city was eventually destroyed by flash floods between 200 and 500 CE.

Samarkand

is an ancient Central Asian city in today’s SE Uzbekistan with a location history that dates back to the Palaeolithic. A key hub on the Silk Road thriving at the time of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia when it was capital of the Sogdian satrapy. Overrun by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE then ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic leaders until conquered by Mongol Genghis Khan in 1220. An Islamic intellectual hub which, in the 14th century became the capital of the empire of Timur (Tamerlane) who is buried in a local mausoleum. The renovated Bibi-Khanym Mosque is a feature of the ancient Registan or city square a centre for the display and sale of local arts and crafts.

Taxila

(City of Cut Stone) is an ancient city in the Punjab, Pakistan is about 30 km NW of Islamabad adjacent to Grand Trunk Road and as a hub along the Silk Road was situated at the junction between the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia. Archaeology dates back to at least c. 1000 BCE and the Achaemenid Empire of the 6th century BCE but absorbed in succession into the Mauryan , Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, and Kushan Empires. But abandoned when trade routes dried up to be finally destroyed by the nomadic Hunas in the 5th century but revitalized by archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham who investigated the ruins in the mid-19th century. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 and now a popular tourist destination. Renowned for an ancient university-like establishment preceding the later Nalanda university in eastern India.

Terqa

About 200 km to the east was Terqa on the then lush Banks of the Euphrates (today overbuilt by the town of Al-Asharah). Preserved in ceramic jars from the pantry of a small private home archaeologists have found a number of clove buds. Cuneiform tablets recorded the transactions of the land-developer owner allowing the site to be dated to about 1721 BCE, Egyptian scarabs also being found on the site, presumably part of a trade route that linked Africa (and thence the Mediterranean) to Indonesia using Indian Ocean currents. Cassia too, used by the Egyptians for embalming and as an incense, was a product of Asia, possibly transported with outher goods and spices from Java and Sumatra by Austronesian traders possibly using the south-east African port of Rhapta.(Burnet, pp. 17-18)

This was a cosmopolitan society of wealthy city merchants called Palmyrenes who oversaw the construction of impressive Greco-Roman sculpture that also had Persia elements. They were a mix of Arabs, Amorites, Arameans and Jews, speaking Aramaic, although Greek was the language used for politics and commerce. Various religions were practiced and gods worshipped. The Palmyrenes were instrumental in the establishment of trading stations along the Roman Silk Road.

Historical fortunes saw the city under the influence of Byzantines, Rashiduns, Ummayads, Abbasids, and Mamluks. Christianity was adopted in the 4th century and Islam a few hundred years later. The city received attention in 2015 when some ancient ruins were destroyed by the militant group Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

Among the various trade routes were:

Amber Road Hærvejen Incense Route Dvaravati–Kamboja King’s Highway Rome–India Royal Road Silk Road Spice trade tea route Varangians–Greeks Via Maris Triangular trade Volga route Trans-Saharan trade Old Salt Route Hanseatic League Grand Trunk Road.

Xi’an

Capital of Shaanxi Province in northwest China, is the oldest of the four great ancient capitals – Beijing, Nanjing, Luoyang and Xi’an and was the starting point of the Silk Road, home to the Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang and now an important cultural, industrial and educational centre. In the 13th century Marco Polo described its massive fortified walls. It is from here that the silk was sent out with the next major trading hub at Dunhuang in the desert of Gansu province about 1500 km away where the nearby Mogao or Dunhuang Caves were a religious (mainly Buddhist) and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, displaying Buddhist art, the first built around 366 CE as Buddhist temples. In 1900 the ‘Library Cave’, walled-up in the 11th century, was the source of now widely dispersed old scholarly manuscripts.

End of trade

Following the disintegration of the spice trade in 1800 world clove production is centred on Madagascar, Sri Lanka, Zanzibar, and Indonesia.

East Indies

Trade with the East Indies and the West had been active from at least the time of the Suvijaya culture. By 100 CE outrigger canoes had ventured at least as far as Madagascar and the African east coast with nutmeg and cloves a part of regular trade in the 12th century. Traders were mostly from Java although there were also Chinese and Malay. As Islam took hold in Indonesia trade deals were struck with resident sultans and as demand for spices increased in the 14th century Malacca assumed the role of major entrepot in the region. Between 1294 and 1478 the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit culture and empire flourished in Eastern Java as a powerful trading group spreading across the Indonesian archipelago to form the largest empire ever to form in Southeast Asia. The capture of Constantinople in 1453 drove Europeans to abandon overland routes, favouring colonial expansion along the world’s sea lanes.

Media Gallery

The Silk Road and Ancient Trade

CrashCourse – 2012 – 10:30

The Early Years of the Silk Road

The Study of Antiquity and the Middle Ages – 2019 – 41:24

The History of Silk

The Study of Antiquity and the Middle Ages – 2019 – 41:17

The Silk Road: Connecting the ancient world through trade

TED-ed – 204- 5:19

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . 1 July 2023 – minor update

Silk Road & Spice Routes

Courtesy UNESCO

https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/silkroad/files/SilkRoadMapOKS_big.jpg