Stuart gardens 1603-1707

Kensington Palace south front with its parterres, engraved by Jan Kip, 1724

This plate was published in Britannia Illustrata (1707-8) and dedicated to “Her most Serene and most Sacred Majesty, Anne”. The plate was reprinted unchanged in 1724. The watercolor tinting is modern. The planting of the parterres was by Henry Wise, but their traditional 17th century layout, of paired plats divided by a central gravel walk, each subdivided in four, appears to have survived from the Palace’s pre-royal existence as Nottingham House.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Isageum – Accessed 9 March 2021

Introduction – Stuart Gardens

The seventeenth century in Europe was a time of transition from a medieval to modern mode of existence characterized by a secular challenge to the prevailing religious worldview. Science and its discoveries were supported by an educated class that looked forward to a more ordered future, rather than backwards to theology, the wisdom of the ancients, medieval magic, feudalism, occultism, and superstition.

International context

Stuart gardens are associaed internationally with the decline of Spain and rise of France with French an international language of society and politics, more of these being fought on the high seas. Europe, especially the Central powers, was engaged in virtually continuous warfare starting with the highly destructive last religious war, the Thirty Years War of 1618 to 1648, beginning as a conflict between Protestant and Catholic states in the splintering Holy Roman empire but gradually absorbing most of European countries and ending with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 which also ended the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648) between Spain and the Dutch Republic when Spain formally recognized an independent Dutch Republic.

In a time of constant warfare England was embroiled in the Dutch-Portuguese War (1602–61), the Anglo-Spanish War (1625–30), the Anglo-French War (1627–29), the Portuguese Restoration War (1640–68), the Irish Confederate Wars (1641–53), the First, Second and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652–74), the Franco-Dutch War (1672–8), and the Nine Years War (1688–97).

The Dutch East India company now extended its influence over the Indonesian Archipelago by taking Jayakarta in 1619 and founding Batavia which was based on the city of Amsterdam. English colonialism began in Ireland and English settlement of New England was more firmly established in 1630. From 1612 English and French colonies were founded in the Caribbean.

Learning & science

The first half of the century was marked by a flowering of art, literature, and science notable in north-west Europe as a ‘late northern Renaissance’. There was a spread of learning through an eagerly communicating European classically-educated intelligentsia. This was referred to as The Republic of Letters which recalled the letter-writing and postal service formerly employed by educated Romans.

Poland’s Copernicus (1473-1543) with his publication De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) had set the stage for the seventeenth century science by placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the centre of the universe, a theory championed by the persecuted Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), and German Johannes Kepler (1571-1630).

In various disciplines major seminal works were being created that would found traditions and help define nation-states across Europe. These are just a selection: for literature of England – Shakespeare, Milton, Donne; Spain – Cervantes; France – Racine, Moliere. In philosophy there was Descartes, Hobbes, Spinoza, Locke. In art – Vermeer, El Greco, Rembrandt, Poussin, Caravaggio.

In 1665 another plague, the Black Death or bubonic plague, struck and this was rapidly followed in 1666 by the Great fire of London which destroyed the homes of 70,000 of the city’s 80,000 inhabitants.

British context

Buoyed by the discovery of the New World Francis Bacon (1561-1626) helped launch a new scientific era with his Novum Organum Scientiarum (1620) , experiment and observation, and peer collaboration.

In England a gathering scientific community joined forces in 1662 to form the influential Royal Society, which instigated the tradition of peer-reviewed articles. Among its esteemed members were Robert Boyle (1627-1691), William Harvey (1578-1657), Robert Hooke (1635-1703), and the towering figure of Isaac Newton (1642-1726/27) who, though possibly the greatest scientist of all time, spent much of his days devoted to alchemy and biblical interpretation. His life was a fine example of this general period of transition – from alchemy to chemistry, magic to medicine, astrology to astronomy, and the mysticism of numerology to mathematics.

Royalty

During this period England was also turned in on itself with constitutional and regime change that encompassed three Civil Wars (1642-1646, 1648, 1650-1651), the execution of Charles I (1649), Oliver Cromwell’s rise to power as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth (1653-1658), the restoration of Charles II (1660), the short reign of James II (1685-1688), and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when parliament deposed a king and brought William of Orange and his wife Mary (the daughter of James II) to the throne. This was a rejection of rule by divine-right and sovereignty of parliament that would permeate the French and American Revolutions especially through the liberalism of English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). At the dawn of the eighteenth century in 1707 England and Scotland joined parliaments to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

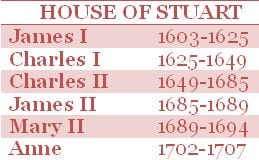

The Jacobean[1] reign of the Stuart dynasty began when king James I assumed the throne in 1603 as a man enthused by the arts and science. In a period of comparative peace up to 1618 (the start of the destructive religio-political Thirty Years War involving most of Europe) the gentry indulged their gardening interests.

The Stuarts were the longest ruling English family dynasty presiding over affairs of state from 1603 to 1707 (with a brief period of parliamentary rule under Cromwell from 1645 to 1660) in a period of revolution and religious conflict. Protestant James I hoped to persuade England, Scotland and Ireland to form a united Britain with a single common law and royal lineage, a vision that earned him the title ‘Little Arthur’ in memory of the great legendary fifth and sixth century King Arthur, acclaimed leader of all the ancient Britons. As James 1 of England and James VI of Scotland he was unacceptable to the English parliament and turned his attention to Catholic Ireland, populating the north with loyal commercially active protestants. James’s son Henry was carefully groomed for his future role as king but died tragically of typhoid when only 18 years old. This left James a son, the sickly stammerer Charles, and a daughter Elizabeth. Charles was to gain health and confidence but made an unsuccessful and unpopular attempt to marry into the Catholic Spanish Hapsbergs. He assumed the throne as Charles 1 in 1625 when James died aged 58.

James had been popular, improving commerce and manufacture, building up the navy and achieving peace in Scotland and Ireland. In contrast Charles was formal, aloof, and authoritarian, proving unpopular by marrying a Catholic French princess and allowing her to practice her religion. He took up residence in Edinburgh in 1633 but his coronation was regarded by the Scots as a formal and unpopular English affair while at the same time he was frustrated by puritan criticism in the English parliament since he believed in rule by the divine right of kings and his own conscience abolishing the parliament. Meanwhile in 1641 the Irish Catholics rose up against the English Protestants and in 1642 Civil War broke out in all countries as Charles’s royalist supporters fought the armies of both Scottish and English parliaments.

Revolutionaries called ‘Diggers’ resisted the unjust distribution of private property, extravagance, excess, and privilege claiming that God had created the Earth for all: it was suggested that waste ground be planted with apples, pears, quinces and walnuts for the benefit of all. Puritans and Calvinists mobilised religion in an attack on artifice as the symbol of a tainted and fallen world that could not challenge God’s perfect natural creation: it was a theme pursued in the literary works of John Bunyan, Milton, and Marvell.[2] Defeated by the Scots in 1645 Charles I was handed over to the English who demanded a constitutional monarchy. Refusing their request Charles was imprisoned on the Isle of Wight as Puritan Cromwell’s revolutionary army established its authority across the country. Convicted of high treason, Charles I was compared to the Roman tyrants Caligula and Nero and publicly beheaded in 1649.

The 18-year-old Charles II was accepted as king in Ireland building up an army that was defeated in 1651 when he fled overseas to live in Aachen for 9 years. Rule in the other countries was by parliamentary committee with Cromwell assuming the title of Lord Protector uniting England and Scotland but assuming unwelcome king-like qualities until in 1658, when his son Richard in an unpopular move inherited his father’s position, lost credibility and the country was effectively without government. Charles II’s offer to return and govern the country was accepted resulting in a full-blown Restoration in 1660.

Charles II was a king who wore his crown lightly, enjoying sport and many mistresses but was nevertheless accepted in spite of taking a Catholic wife. In a massive London Fire he popularly assisted, with his brother James, in putting out the flames.

For about 20 years England had been at war with the Dutch over trade routes. In 1667 the Dutch sailed down the Thames, crushing the English fleet of Charles II and, in a humiliating display of strength, towing the royal flagship back to Holland. Charles appealed to his French cousin Catholic Sun King Louis XIV for support in his battle with Holland and forged a secret alliance, the Treaty of Dover, but to no avail. Though Charles had fathered many illegitimate children he had no heir from his wife Catherine and it seemed likely that his Catholic brother James would inherit the throne. Hope for reconciliation between Holland and England was placed in the marriage between Charles’s daughter Mary and Protestant Dutchman William of Orange. Charles II’s unpopularity increased, the disapproval rising when he dissolved his critical parliament, now divided into Whigs and Tories. On his deathbed in 1685 James brought a priest to hear Charles’s confession and Catholic James II was crowned monarch.

James II was not put off by Protestant detractors as he encouraged the Catholic faith in Ireland and in 1768 his wife gave birth to a potential son and heir, again named James. Simmering Protestant rebellion changed to outright support for Dutch Protestant William and his wife Mary in Holland and William, taking his opportunity, invaded with a massive fleet of over 400 warships. It was a bloodless coup but William refused to accept a secondary role to Mary his English Protestant wife nevertheless accepting a Declaration of Rights that limited his power as king. The chastened James meanwhile laid siege to northern Ireland’s Protestant Londonderry, William eventually breaking the long siege, the two armies eventually meeting in southern Ireland’s Battle of the Boyne, decisively won by William. James II fled to France to live in a palace where his son James was raised as a devout Catholic, this was the palace formally occupied by Louis XIV who now moved into the famous Palace at Versailles.

Perhaps as a reminder of Dutch naval achievement William commanded the architect Christopher Wren to build the Greenwich Observatory. When Mary died of smallpox in 1694 there was no heir to the throne, the crown passing to Mary’s Hanoverian Protestant cousin Anne who became Queen when William died in 1707. This was an unpopular succession for the Scots but by the time Anne died in 1714 an Act of Union had been negotiated uniting Scotland and England into the Great Britain of today.

The Worshipful Company of Gardeners was given its Royal Charter in 1605. Gardening was now well established across much of society, the royal court, gentry, merchants and wealthier artisans and, as always, the source of social rivalry as a means of defining status.

Between 1550 and 1660 land tenure (see property and ownership) changed drastically as enclosure was introduced along with a lack of leniency with tenants made more difficult by the absence of landlords attending to business in the ‘city’.

Garden design

The geometric more-or-less rectilinear knot gardens were now being replaced by more organic scrolling designs with sanded walks, the parterres that were now popular in France. Parterres became a specialist domain of horticulture incorporating different design elements and national preferences.

Inspiration for new garden design came from abroad. Aristocrats on the ‘Grand Tour’ admired the terraced hillside gardens of Italy with their sculptures, staircases, curved balustrades, fountains, grottoes, cypresses, and walled gardens with their graded levels of sensory experience. Producing such gardens required wealth, engineering skills and major excavation – and as many garden elements alluded to mythological and other symbolic ideas the gardens tended towards extravagant gestures of a wealthy educated elite.

To these design ideas can be added some Jacobean eccentricities like shell-covered ‘mountains’, a fascination with grottoes (often treated as a woman’s domain with shells a collecting fad of the time), automata, and fantastic mythological statues, nymphs, water goddesses and the like, along with elaborate fountains.

Royalty, as always, set the gardening agenda for the social elite. Kensington Palace, originally a Jacobean mansion, was purchased in 1689 by the newly crowned couple William and Mary, who employed Christopher Wren to create what would become the preferred royal residence (which was officially St James’s Palace) for 70 years. After William III’s death in 1702, the palace was further extended by Christopher Wren and became the residence of Queen Anne who commissioned an Orangery, modified by John Vanbrugh, and completed in 1704. The interior included carved detail by Grinling Gibbons to enhance its use as both a conservatory and venue for entertainment. Outside was added a 121,000 m2 baroque parterre of scrolled hedges and cone-clipped trees, set out by Henry Wise, the royal gardener and later removed by Charles Bridgeman, who succeeded Henry Wise as royal gardener and redesigned the gardens to a form that is recognizable today.

With the Restoration came new ideas about the estate gardens as the scale was again extended, with the same grandeur but with long vistas joining parkland that would eventually merged, in the distance, with the surrounding countryside. Continental influence still prevailed as, in France, Charles II’s cousin, the absolutist monarch Louis XIV, employed the great designer André Le Notre to set out his long avenues and canals, the central axis cutting through parterre and woods to stab the horizon, the lateral avenues decorated with statuary, water features and fountains in a manner that would culminate in the great garden at Versailles. England’s elite produced more modest imitations of Versailles that included radiating avenues, canals, parterres, topiary and, above all, vistas terminating in statuary, obelisks or buildings, many of these creations persisting late into the 18thcentury.[U,p.117] There arose at this time a loose distinction between busy and enclosed Dutch gardens with their topiary, potted plants, espaliered trees, parterres planted with bulbs, and the sweeping open vistas of the French parc although in reality the styles were often blended, and with a liberal admixture of Italian classicism.

In any event, gardens on this scale required the specialist skills of much sought-after experienced designers who could take them through to successful completion. By the time Anne came to the throne in 1702 awareness there was a gathering concern for the exorbitant expense of laying out entire landscapes with elaborate parterres and long straight avenues of trees all requiring hundreds of labourers.

The commoner

While royalty enjoyed high fashion of Italianate gardens the small gentry, yeomen and farmers used gardens mostly to supplement their diet, although there was also pride to be taken in the flower garden.

Women played a specific role at all levels of society. On the estate, in true Roman fashion, it was the woman’s job to manage the staff of servants and labourers and the efficient use of domestic animals, dairy, kitchen, herb garden, vegetables, fruit trees, bees and more) while the husband was away and to entertain the guests when he was at home. She was also expected to know about medicines, potions, perfumes, oils, scents, and soaps.[4]

Plant introduction

With the accession of William III and Mary II in 1689 there was a co-regency until Mary died in 1694, William ruling alone until his death in 1702, when he was followed by Queen Anne.

William and Mary introduced Dutch horticultural expertise to England. William had horticultural and botanical connections with Dutch horticulture, at this time, well in advance of that in England. In their gardens at Het Loo in Holland the pair had built up a vast potted collection of exotic plants and these were brought to England. In 1675 William removed the restriction on the Dutch east India Company to import exotic plants.

At the royal residence at Hampton Court of 1702 the garden was reconstructed into a Great Maze and formal geometric Privy Garden with a turfed parterre á l’Anglais (turf and coloured gravels) style that would soon to fall out of favour. There were three walled gardens (auriculas, container plants, exotics) and three hothouses with state of the art underfloor heating like the hypocaust used in Roman baths and buildings with the beds in the hothouses warmed with manure and tanners bark to enhance the great display of plants from Barbados, Canaries, East Indies and the Cape, the potted plants brought outside in summer.[3]

Wealthy women, closeted on their estates while husbands dealt with affairs of state, played a major role in garden history from this time on. An early English example in Mary Duchess of Beaufort’s (1630-1715) influence through the massive family estate at Badminton where she had a 100’ orangery constructed, a stove house that could rival the Queen’s, filled with the latest exotic novelties collected from the South African Cape, West Indies, Virginia, India, Sri Lanka, China and Japan sourced via her botanical contacts including Hans Sloane of the Chelsea Physic Garden her London neighbour. Her collecting started in the 1690s and provided a diversion during her widowhood. Among her botanical treasures were tropical fruits like banana, guava and paw-paw, and ornamental curiosities of the day like nerines, hibiscus and aloes. At Beaufort House, her London residence in Chelsea, there was a terraced sunken flower garden where she grew jonquils, fritillarias, tulips and anemones along with carnations and paeonies along with her favourites, a prize collection of auriculas. Badminton became home to her proud collection of South African ‘geraniums’.[5] Her botanical enthusiasm resulted in a personal herbarium donated to Sir Hans Sloane and later housed in the Natural History Museum, and a florilegium of drawings of her favourites by Everhardus Lychicus kept in the library at Badminton. Her best known plant introductions are the zonal pelargonium, Pelargonium peltatum, and the blue passion flower Passiflora caerulea.

Bishop Henry Compton (1632-1713), appointed Bishop of London in 1675, resided at Fulham Palace where he assembled plants traded with American colonists. He even passed his gardener George London (who had established a popular nursery at Brompton) to William and Mary at Hampton Court in 1689. The Brompton Park Nursery covered 100 acres between Hyde Park and Kensington held a stock of about 40,000 plants, reaching its height of prestige in 1693-4.(Hobhouse p. 135)Fulham Palace at that time contained ‘a greater variety of curious exotic plants and trees than had at that time been collected in any garden in England’ as his garden was described when he died in 1713 (Brown 1999, p. 61) In his stove houses he cultivated England’s first coffee plant. He was appointed Deputy Superintendent of the Royal Gardens to William III and Mary II and also Commissioner for Trade and Plantations. He corresponded with John Bannister in the West Indies and then Virginia receiving in return, plants (plants were also sent to Chelsea Physic Garden and Oxford Botanic garden) drawings, seeds, and herbarium specimens from which the Bishop’s close friend John Ray compiled the first published account of North American flora in his Historia Plantarum (1688) (see Wikipedia)

Mulberries were distributed across the land in the hope that a silk industry would result. Food for the table came directly from the, mostly nearby, land: meat from cows, pigs and sheep; geese, chickens, ducks; fish from local rivers; bread from locally milled grain; fruit from the orchard either fresh, stewed or preserved (apples, pears, cherries, peaches, apricots, redcurrants, blackcurrants, gooseberries, raspberries, quinces); honey from the bee hives; Beer and some other alcoholic beverages (e.g. some wines, perry, cider) from the estate brewery. It was the luxuries that were bought in: spices, sugar and wine.[8]

Banister’s plants included Magnolia virginiana, Acer negundo, Liquidambar styraciflua, Abies balsamica, Aiton’s Hortus Kewensis of 1789 crediting Compton with over 40 new introductions.[7]

Landscape

Charcoal was used in blast furnaces and in the Midlands the Forest of Arden practically disappeared.

Up to about 1730 Enclosure of fields was largely a matter of private agreement between lords but around the time of George II this became more a matter of Parliamentary Act as land between Yorkshire and Dorset was converted from open strip fields to the hedge-rowed squarish fields of today. It is this period of enclosure that entailed the final removal of much of the remaining forests, heathland, moors, marshes and fens which were cleared, drained, converted to fields and settled.

‘It is the totality of these new enclosures, beginning perhaps in the 17th century and increasing rapidly through the 18th and19th centuries, together with the industrial and urban development . . . that mark the last 250 years . . . ’[6]

Literature

John Evelyns works, especially his 1693 translation from the French of de la Quintinye’s The Complete Gardener were perceived as a great advance. and his Sylva commissioned by the Horticultural Society to address the lack of wood needed to maintain the shipbuilding industry of the British navy.

Thomas Hill The Gardener’s Labyrinth (1577)

Francis BaconOn Gardens (1625)

John Evelyn Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest Trees (1664). A classic and highly popular book on trees by the learned diarist, country gentleman, and commissioner to the court of Charles II

John James The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712)

William Lawson The Country Housewife’s Garden (1618)

Thomas Tusser Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandrie (1573)

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

The period from 1500 to 1800 can be viewed a rural period of respite between survival in the Middle Ages and the onset of the Industrial Revolution. The upper classes enjoyed greater prosperity and engagement with the continent and arts, but the situation and political representation of the poor was dismal, leading to the Peasant’s Revolt and ultimately Civil War. Post Reformation affluence came in part from the monasteries but the creation of large open spaces often entailed moving people off the land. From the late 16th century there was greater attention to water management for the growing numbers of sheep, especially in East Anglia, through the creation of leats, channels, dams, and careful field flooding.

—

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019

. . . revised 9 March 2021

Grand Menshikov Palace

In 1707, four years after Peter the Great founded Saint Petersburg, coastal grounds were donated to Aleksandr Danilovich Menshikov who commissioned the architects Giovanni Maria Fontana and Gottfried Schädel to build his residence, the Grand Menshikov Palace. This was completed between 1710 to 1727. The central Palace is connected by two galleries to domed Japanese and Church Pavilions. The Lower Garden is decorated with fountains and sculptures. This is a magnificent example of the formal rectilinear parterre style of the period.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Andrew Shiva – Accessed 9 March 2021

BRITISH MONARCHS

SAXON - 802-1066

DANE (Viking) = D

Egbert - 802-839 - Wessex

Æthelwulf - 839-856

Æthelbald - 856-860

Æthelbert - 860-866

Æthelred I - 866-871

Alfred-the-Great - 871-899

Edward the Elder - 899-924

Athelstan - 924-939

Ælfweard - 924

Edmund I the Elder - 939-946

Eadred - 946-955

Eadwig the All Fair - 955-959

Edgar I - the Peaceful - 959-975

Edward the Martyr - 975-978

Æthelred II - Unready - 978-1013

Sweyn I Forkbeard - 1013-1014D

Æthelred II Unready - 1014-1016

Edmund Ironside - 1016

Canute the Great 1016-1035 - D

Harold Harefoot - 1035-1040 - D

Harthacanute - 1040-1042 - D

Edward t'e Confessor 1042-1066

Harold II - 1066

Edgar Ætheling - 1066

NORMAN - 1066-1154

William I - 1066-1087

William II - 1087-1100

Henry I – 1100-1135

Stephen of Blois – 1135-1154

PLANTAGENET - 1154-1485

Henry II – 1154-1189

Richard I Lionheart – 1189-1199

John Lackland – 1199-1216

Henry III – 1216-1272

Edw' I Longshanks – 1272-1307

Edw' II of Carnarvon - 1307-1327

Edward III – 1327-1377

Richard II – 1377-1399

Henry IV – 1399-1413

Henry V – 1413-1422

Henry VI – 1422-1461

Edward IV - 1461-1483

Edward V - 1483

Richard III - 1483-1485

TUDOR - 1485-1603

Henry VII – 1485-1505

Henry VIII – 1509-1547

Edward VI – 1547-1553

Lady Jane Grey/Dudley – 1553

Mary I/Mary Tudor – 1553-1558

Elizabeth I – 1558-1603

STUART - 1603-1714

James I – 1603-1625

Charles I - 1625-1649

Civil War – 1642-1651

Commonwealth - 1649-1653

Protectorate – 1653-1659

Charles II – 1660-1685

James II (VII Scotl'd) -1685-1688

Mary & William - 1688-1694

William of Orange – 1694-1702

Anne – 1702-1714

HANOVER - 1714-1901

George 1 – 1714-1727

George II – 1727-1760

George III – 1760-1820

George IV – 1820-1830

William IV – 1830-1837

Victoria – 1837-1901

SAXE-COB' GOTHA 1901-1910

Edward VII - 1901-1910

WINDSOR – 1910->

George V – 1910-1936

Edward VIII – 1936

George VI – 1936-1952

Elizabeth II – 1953->