Theophrastus

The Father of Botany

Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BCE) lived in ancient Athens, Greece, 2300 years ago, two millennia before Australia was sighted by Europeans. What possible relevance could he have for us today? Theophrastus’s voice speaks to us from the very beginnings of modern Western science and botany. He makes us think about the power of cultural tradition and its need for constant reappraisal, and he demonstrates how a knowledge of history can give us many insights into today’s world. We experience the presence of this man today in Australia not only because he built the foundations of plant science in the Western world as a whole but, more specifically, through the methods he used for collecting, studying (from plant growing in a living garden collection), describing, and distributing plants at the time of ancient imperial Greece. His example would be followed by scholars of the European Renaissance from the fifteenth century on who were tutored in the literary works of the classical world. In his writings we see a blueprint for the economic botany of the 18th century European Enlightenment and its colonial expansion, a time when pride of place was given to natural science and plants. But there was also the much more general influence of Greek and later Roman cultures in creating the ethos of the British Empire that would transform the vegetation and landscape of not only the continent of Australia but much of the ‘western’ world and beyond.Historical context

The discovery of ways to smelt and work iron originated in Asia Minor (Turkey) in about 1,200 BCE. This new technology had far-reaching consequences. Not only did it increase the efficiency of agricultural tools, the armoury used in warfare, and the utensils of daily life but it indirectly created a new social order. In addition to the traditional wealthy land-owners there now arose a new influential class of merchants and traders. Sea trade had always been important in Greece because Greek cities were isolated on islands and mountains, but this was a new breed of men familiar not only with the practical worlds of agriculture, commerce and manufacture, but with foreign cultures and their ideas, especially those of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia and Crete. Metal coins were first minted in the eighth century BCE in the ports and trading centres of Ionia (the western Aegean coast of present-day Turkey) which was at that time part of Greece with cities like Miletus being major intellectual and trading centres for the Mediterranean. By the 6th and 5th centuries BCE peoples across the world had entered what we now call the Axial Age (c. 800-200 BCE), subjecting their beliefs to critical examination and developing new social structures. In this period of intellectual gestation we see the emergence in the East of Chinese Taoism and Confucianism, Indian Buddhism and Jainism, and Persian Zoroastrianism. From the Mediterranean region was emerging not only the Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Judaism and Islam but also a special mode of analytic thought. Chief among these men (these societies were all male-dominated) were the Ionian or pre-Socratic philosophers who were engaged in a critical re-appraisal of all aspects of human knowledge and activity, challenging long and entrenched conservative traditions of thought. Ionia was a small 150m-long coastal strip on the western coast of Today’s Turkey opposite the island of Samos and with vibrant trading towns of Miletus, Ephesus, and Priene. No doubt the interchange of ideas through trade and the advent of (classical-style) democracy reinforced the feeling that, regardless of supernatural beliefs, the activities of the gods and priests humans could, by careful observation and the use of reason, begin to not only understand the workings of the physical world but also play a part in forging their own destiny. There are many ancient written references to plants and short list but two substantial botanical records that pre-date those of Theophrastus deserve special mention.[28] Firstly there is a list of plant names written c. 668-627 BCE on clay tablets found in the royal library in Nineveh, the capital of Mesopotamian Assyria. Under the ruins of the palace of King Ashurbanipal the list of 200 names are listed in Sumerian and translated into Akkadian. The list includes synonyms (alternative names for the same plant) so there are altogether about 400 Sumerian names and 800 Akkadian and they are arranged according to their uses. The second is a list of about 230 plants found in the work, known as the Hippocratic Corpus, attributed to Hippocrates (c.460–370 BCE) but authorship uncertain. Hippocrates was a physician from the Aegean island of Kos, his name known to us today through the doctors’ Hippocratic oath. Apart from the list of plants related to medicines and edible parts the Hippocratic Corpus also contains a lengthy discussion of plant germination and development. Opposite Ionia on the eastern shores of the Aegean Sea was Greece and its capital Athens. Here arose what many scholars consider the world’s greatest ever independent thinkers, who built on the work of the former Ionians and others, made famous by a teacher-student line that runs from Socrates (c. 469–399 BCE) to Plato (c. 424–348 BCE), to Aristotle (384– 322 BCE) and then to Theophrastus (c.371-287 BCE). Perhaps in the desire to find common ground among the great divergence of religious and other views it became necessary to pare arguments down to their simplest, least subjective and least controversial elements, cutting away all possible sources of confusion, complexity, and uncertainty – and therefore disagreement. During this Classical period (lasting for about two centuries) these men, an others like them, laid the foundations of modern science and much of present day Western thinking about politics, medicine, law, astronomy, literature, art, and ethics: Hippocrates in medicine; Euclid and Pythagoras in mathematics; Aristarchus, Eratosthenes and Hipparchus in astronomy; Archimedes in engineering; and many other great names (see Socrates, Plato, Aristotle).His life

Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE) was born at Eresos (today’s Skala Eresou) a village on the island of Lesbos just off the west coast of present-day Turkey, the son of Melanthus a wealthy fuller (someone who prepares wool for the textile industry). Much of what we know of Theophrastus comes from biographer Diogenes Laertius who lived in the third century CE and whose single known publication Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is a major source book for the history of Greek philosophers and philosophy.[3] We learn, for example, that Theophrastus was ‘a most benevolent man, and very affable’ and that his true name was Tyrtamos (or Tyrtanios) as the name Theophrastus (theios – divine, phrasis – diction) was a nick-name given to him by Aristotle as a tribute to his eloquence. Diogenes Laertius attributes 227 treatises to Theophrastus on a wide range of topics: sadly all are now lost with the exception of the two on plants, one on stones, and a few other disputed manuscripts. One of these was a work on the Pre-Socratic philosophers which, though lost, has remained in part through incorporation in the works of others. A further text, Characters,[27] written in about 320 BCE is attributed to Theophrastus and made a major contribution to the literary tradition of character-writing which became especially popular during the Renaissance when it was known as Descriptio. He is attributed with the view that happiness depends on external influences as well as on virtue and to have declared that ‘life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom’,[30] and was opposed to eating meat because it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. Non-human animals, he said, can reason, sense, and feel just as human beings do.[31] The most comprehensive current synthesis of his works is given in The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy[35] while extended accounts of his life and botany have been given by Greene and Morton. Diogenes Laertius tells us that one of Theophrastus’s pupils, Demetrius of Phalerum, became Regent of Athens for ten years and possessed an admirable garden that contained exotic plants as well as indigenous ones.Meets & befriends Aristotle

As a young man Theophrastus had studied on his island of Lesbos before travelling to Athens to study at the philosopher Plato’s famous Academy. Plato’s student Aristotle had, when 17, moved to the Academy in Athens remaining there until he was 37. Aristotle was a Macedonian born at Stageira near present-day Thessaloniki, his father Nicomachus[33] was personal physician to the court of King Amyntas II of Macedon but he died when Aristotle was still young. Like other privileged children Aristotle was taught athletics, music, and Homeric poetry, but his guardian Proxenus decided that this education should be extended by enrolling Aristotle in Plato’s Academy in Athens. From about 530 BCE the educated young men of Athens would learn Homer’s works by heart so this would have been one of his subjects. Plato had died in 347 BCE, Aristotle moving to Assos on the Turkish coast where he was hosted by King Hermias, opening an academy of his own, working on biological subjects and marrying, in about 345 BCE, Pythia the adopted daughter of the king. Hermias was slaughtered when Assos was sacked by Persian soldiers but Aristotle fled to Macedonia where he tutored the young Alexander the Great, son of King Philip II of Macedon before taking a ‘honeymoon’ on Lesbos with his new wife. It is uncertain whether Theophrastus met Aristotle in Asia Minor in 347 BCE or on Lesbos in 344–342 BCE, but he travelled with Aristotle to Macedonia in 342–335 BCE and then to Athens where Aristotle set up his Lyceum in 335 BCE. We have no formal record of the years Aristotle spent on Theophrastus’s home island of Lesbos but we do know that though this was likely a ‘honeymoon’ he had plenty of time for Theophrastus (Theophrastus aged 24, Aristotle aged 37) the pair, or group, also travelling to Asia Minor and Macedonia. On Lesbos the young men studied the animal and plant life, Aristotle’s favourite haunt being the lagoon known today as Kalloni Gulf. The years 345-342 BCE were spent on this island and although there is no precise record of this time it seems the two men made a pact: together they would make a detailed study of the living world. Aristotle was to specialise in animals, Theophrastus in plants.[1] This we may regard as a critical point in the emergence of modern biological science. Ancient Greeks had inherited vast astronomical catalogues from Babylon and Egypt but we know of no similar biological tracts. Certainly the two had access to medicinal information and general folk-wisdom but they were effectively starting from scratch in their biological quest, and their treatises Historia Animalium and Historia Plantarum , their scientific enquiries into animals and plants, are likely the first of their kind. Aristotle’s wife Pythia died in 342 BCE and in the same year King Philip II of Macedon invited Aristotle, in the Greek tradition of private tuition, to become tutor to his 13 year old son Alexander (356–323 BCE), the future military hero Alexander ‘The Great’. In Macedon Aristotle formed the Royal Academy of Macedon becoming its Head and for two years tutoring not only the young Alexander but two other future kings: Cassander (c. 350–297 BCE) the future King of Macedon from 305 to 297 BCE, and Ptolemy I (c. 367–283 BCE) who was to become one of Alexander’s generals and subsequently ruler of Egypt from 323–283 BCE. Alexandria, named after the military hero, became famous under Ptolemy I for its magnificent library and museum becoming a centre of academic research and taking over the torch of learning from Athens.Gymnasia – the Academy, Lyceum & Cynosarges

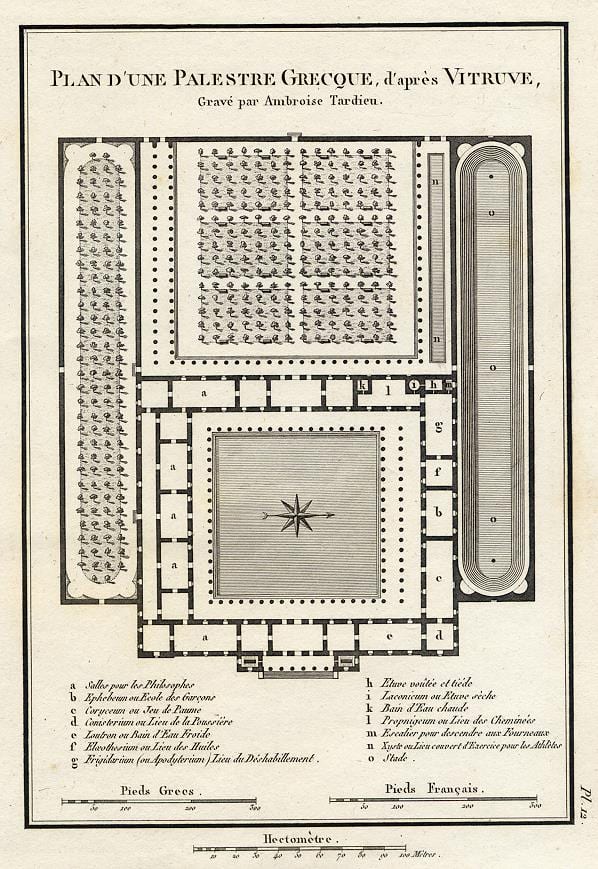

The Lyceum was just one of several education establishments in Athens called gymnasia. In ancient Greece all-male gymnasia were training institutions for the country’s future leaders. The Latin saying mens sana in corpore sano (a healthy mind in a healthy body) was attributed to the Ionian philosopher Thales and taken very seriously. The gymnasia provided both physical and intellectual training that included a strong military component along with philosophical discussions on topics akin to modern-day science, mathematics and astronomy as well as studies of music and literature. Athletics competitions celebrated heroes and gods and to win any of the events was considered a great honour. Participants were naked (gymnos – naked) allowing aesthetic appreciation of the male body. Notes were taken during the lectures, original research was carried out, and there was an associated library. Though modern universities are often dated to autonomous organizations of scholars in Medieval Europe, the similarity between ‘academia’ and the Greek gymnasia is clear: it was in the 4th century BCE that the first philosophical schools were founded as part of these gymnasia and they were, in effect, the first universities. Athens had three major public gymnasia:the Academy, or Akademia as it was named, was founded by Plato in approximately 385 BC as part of an enclosed sacred grove of olive trees north of Athens. The source of the name is uncertain, possibly recalling the old name Hekademia which dated back to at least the 6th century BCE, linked to a legendary Athenian hero Akademos. The grounds, dedicated to Athena the goddess of wisdom, were designed by the civic-minded and wealthy patron Kimon, an eminent statesman and military hero. The school continued on the same site until Athens was overrun by the Roman forces of General Lucius Sulla in 86 BCE when the Greek peninsula fell under Roman rule. However, the Neoplatonists revived the Academy in the early 5th century CE by which time it was now within Athens surviving until Byzantine Emperor Justinian, regarding it as a threat to Christianity, closed it in 529 CE. Tuition at Plato’s Academy was based largely on mathematics, that of the Lyceum on history, botany and zoology.[6] The Cynosarges we know less about but it was home of the Cynic School of Philosophy founded by Antisthenes a student of Socrates.The Lyceum

In 335 BCE, when aged 49, and just three years after the conquest of Greece by Macedonia, Aristotle returned to Athens to head his own academy, the Lyceum (built on the site of a sanctuary dedicated to the god Apollo Lykeius, Apollo of the Wolves) which had existed on the site for some time. Here, where there was parkland, shrines, military training and a racetrack, Aristotle ‘rented a few buildings and set up his school‘.[22] At the Lyceum Aristotle would take a morning stroll (gr. peripatos) with his advanced students to work on ideas of current interest while, in the evening, there would be a further stroll for the benefit of those taking a more general interest in the knowledge available at the school. From this tradition of discussion while strolling in the grounds of the gymnasium the scholars at the Lyceum became known as ‘peripatetics’. During the 12 years he devoted to the school Aristotle completed his masterful Metaphysics (so-named because it was ‘after’ his ‘physics’ in book sequence), also the Politics and Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle[24] and Theophrastus lectured on a wide range of topics but in the biology lessons Aristotle concentrated on the study of animals and plants were the domain of Theophrastus although Aristotle did write a treatise on plants, θεωρία περὶ φυτῶν, which is now lost. Though there are many botanical comments scattered through his other writings (these have been assembled by Christian Wimmer in Phytologiae Aristotelicae Fragmenta, 1836) they give little insight into Aristotle’s botanical thinking. Theophrastus would have been influenced by the senior Aristotle but botanical historian Alan Morton has no doubt that botanical work has been correctly attributed to Theophrastus. Aristotle made no secret of the fact that he had encouraged Alexander in his eastern conquests and had published works supporting Macedonian rule. Athens fell under Macedonian rule in In 338 BCE when the army of Philip II defeated the combined forces of Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea. As a result of tensions between the Macedonians and native Greeks Aristotle was forced to flee Athens with his family in 322 BCE when resentment of Macedonians was at its height. The Lyceum, with its precious library and garden, was passed on to his friend Theophrastus, and Aristotle returned to his homeland where he died the same year aged 63. In his will Aristotle requested that Theophrastus be his successor as Head of the Lyceum: his daughter was given in marriage to Nicanor an officer in Alexander’s army; real estate, household property and money to Herpyllis (possibly a second wife). He disposes of about 12 slaves, commissions statues to his parents, guardians and others, asking to be buried next to his wife Pythia. Theophrastus retained his position at the Peripatetic School of Philosophy for 36 years, between Aristotle’s exile in 323 BCE and his own death in 286 BCE. At the time of his death the Lyceum had a temple to the muses, a museum containing maps, and a bust of Aristotle. There was also the house and garden with colonnades which Theophrastus bequeathed to the institution, saying in his will ‘ … Let me be buried in any spot in the garden which seems more suitable, without unnecessary outlay upon my funeral or upon my monument’. No burial remains have been discovered at the present-day site excavation. As metics (resident aliens) both Theophrastus and Aristotle were immigrants who were not allowed Greek citizenship, Theophrastus being from a distant island and Aristotle a Macedonian.[2] As a consequence they were not permitted to own property and Aristotle had only been able to lease the Lyceum. However Theophrastus, through his influence, managed to overturn the law and purchase the Lyceum outright. Under his leadership the school proved extremely popular, drawing about 2,000 students, presumably a cumulative total. Diogenes reports that when Theophrastus died there was a public funeral, ‘the whole population of Athens, honouring him greatly, followed him to the graveside.’ Theophrastus was succeeded by Strato (Straton) ‘The Physicist’ of Lampsacus (c.335-269 BCE) who continued the emphasis on empirical studies. When Strato died ‘scientific’ activity moved to Alexandria and the institution lapsed while Plato’s Academy persisted until dissolved by Justinian in 529 CE.[32] The school limped on until destroyed by Sulla in 86 BCE although it was later restored in the first century CE. Within the grounds there was a library, museum, and botanic garden.The Lyceum today

In 1996 while excavating space for a new Museum of Modern Art, undisputed remains of the ancient Lyceum were uncovered at Vasillis Sophia. As a result an outdoor museum was constructed and the perimeter of the site planted with herbs of that times including lavender, mint, sage, thyme and oregano, together with indigenous trees – pomegranates, olives, laurel, cypress and acacias to give visitors a sense of what the site would have looked like in antiquity. It was officially opened in summer 2013.[12]

On the 16 June 2014 I visited this incomplete excavation of the Lyceum on a personal pilgrimage to view the remains of the site where these two great men of science and reason had worked – two men who I judge have indirectly influenced my life more than any others – Theophrastus through his botanical science and Aristotle through his monumental impact on science and Western thought in general. Theophrastus’s lecture notes are now nearly 2,500 years old. Roman General Sulla (138-78 BCE) during the Roman conquest of Greece subjugated Athens in 87-86 BCE including the Lyceum where he ‘chopped down the ancient plane trees that lined its winding paths and built siege engines from their wood‘ but damage may have occurred earlier. When the the great Roman chronicler Cicero visited the site on a homage to Aristotle in 97 BCE all he found was a wasteland.[22] Ironically it appears we owe our knowledge of Aristotle’s work to Sulla who plundered a library containing some of Aristotle’s works, returning them to Rome. We now know that about two thirds of Aristotle’s total works have been lost.[22]

Modern interpretation signs on this site justly, I believe, describe it as ‘one of the most important places in the history of mankind’.[21] Aristotle’s work had greater breadth than that of the brilliant Plato and it foreshadowed much of the precise critical thinking needed to produce modern science. Unlike Plato, Aristotle grounded his ideas in empirical reality, extending the knowledge of his day through his analysis of the structure of logic (this work later compiled as the Organon), and his general commentary on philosophy and the physical world. Collectively his works represent an extraordinarily erudite exposition of the philosophical and scientific knowledge available to the classical world.

In the medieval Christian Scholasticism and Arab philosophy that followed in the wake of the collapse of the classical world Aristotle (referred to as ‘The Philosopher’) was the undisputed source of wisdom and authority in every discipline. Some measure of the intellectual stature of this man can be comprehended when we realise that his ideas remained unchallenged for more than eighteen centuries. His contribution has been acknowledged by scientists like Linnaeus and Darwin but classical studies are now unpopular with scientists as are formal studies of the history and philosophy of science. So many botanists have not heard of Theophrastus and Aristotle does not inspire interest, being treated as a quaint inconsequential figure of the distant past.

The Lyceum took pride in its tradition of careful observation of causal connections, critical experimentation and rational theorizing, all harnessed to closely scrutinise the prevailing beliefs. Theophrastus defied both the superstitious medicine employed by the physicians of his day, called rhizotomi, and the control exerted over medicine by priestly authority and traditions lacking empirical evidence.

Lyceum excavation in 2014

The Lyceum was part of a gymnasium complex rented by Aristotle Aristotle was succeeded as Head of the gymnasium by his friend Theophrastus, now known as the Grandfather of Botany. Linnaeus had referred to Theophrastus as the father of botany but Linnaeus himself was subsequently given the title Father of Botany, Theophrastus is perhaps more appropriately known as its grandfather: it was he who founded plant science while Linnaeus had laid the foundations of taxonomy

Photo: Roger Spencer, 16 June 2014

Lyceum library

Knowledge in the ancient world was preserved in libraries either as scrolls or the more easily handled book-like and bound hand-written sheets (of paper, vellum of calf, papyrus, or parchment made from the skin of domesticated animals especially cattle, sheep and goats) bound into a codex (pl. codices). Historian and geographer Strabo (64/63 BCE-c.24 CE) claimed the Lyceum library as the most important of the pre-Roman libraries in the ancient world (mainly bacause it contained the works of Aristotle) only being eclipsed later by the more famous libraries at Alexandria in Egypt, and those at Ephesus and Pergamon (Bergama) in today’s coastal western Turkey.[15][16]

Founded in the pre-Hellenistic age the Anatolian city of Pergamon under King Eumenes II (197–159 BCE) rose to prominence as a wealthy administrative center with magnificent sculptures and architecture and rivalled only by Alexandria and Antioch. After forming an alliance with Republican Rome and severing ties with Macedonia the city was bequeathed to the Roman Republic in 133 BCE by Attalus III (c. 170 BC – 133 BC), the last Attalid king of Pergamon who ruled from 138-133 BCE who neglected his kingly duties, devoting his time to medicine, botany, and gardening. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 Pergamon becoming part of the Ottoman Empire. The library, according to historian Plutarch (c. 45-50- c. 120-125 CE) housed about 200,000 manuscripts which were written on parchment, rolled into scrolls or bound into codices, and then stored on the shelves. Built by Eumenes II the Pergamon library was, at this time, second only to the Great Library at Alexandria (see Wikipedia). A legend recounted by Plutarch (c. 45-50- c. 120-125 CE) suggests that Mark Antony seized all the scrolls as a gift to his new wife Cleopatra in 43 BCE in an effort to restock the Library of Alexandria which had been plundered in 47 BCE. Emperor Augustus later returned some scrolls and though the library persisted into the Christian era the collection was much impoverished.

Strabo claims the valuable Lyceum library collection in Athens was passed by Theophrastus to a bibliophile Neleus who took it to Skepsis a mountain village near Assos on the Turkish coast before it was purchased by an Athenian collector and then stolen and taken to Rome by General Sulla in 86 BCE when the Roman army overran Athens. In the first century CE it is recorded that an Andronicus of Rhodes worked at editing and ordering the works although copies were probably made as the great library at Alexandria contained works of both Aristotle and Theophrastus.[25]

We can assume that early scholars interested in plants would have had access to, and been strongly influenced by Theophrastus’s work. Sadly, many modern botanists are unaware of the giant step in plant science that Theophrastus’s work represents, it is a botanical tour de force for his day and a masterpiece of Greek thought moving from first principles to a scholarly analysis (not least of which is the detailed terminology for plant parts). Most interest in his day would have been firmly grounded in medicinal uses and dubious potions and the utilitarian interests of plants as food, ornament and structural material (which would be the concern for the next 1,200 years after the decline of the Classical world).

Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) was one of the last western commentators to mention Theophrastus’s work before it was temporarily lost to the western world. After the destruction of ancient libraries, mostly by Christians, many works passed into the protection of the Muslim world to be recovered during the reconquest of Moorish Spain, most notably from Toledo, Kingdom of Castile, in 1085 where most of Aristotle’s works, written in Arabic, were held. Here the Italian Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114 – 1187), the most important translator among the Toledo School of Translator, translated scientific books from Arabic into Latin. Some of the books, originally written in Greek, were unavailable in Greek or Latin in Europe. His translations inspired medieval Europe in the 12th century by converting Arab and Greek astronomy, medicine and other sciences into Latin.

Supposedly at the request of Thomas Aquinas, William of Moerbeke (1215-1235 – c. 1286), a Dominican Flemish monk working in the Greek Pelopponese, translated the complete works of Aristotle directly from the Greek into Latin when the Byzantine Empire was under Roman Latin rule. Many of the copies of Aristotle in Latin at that time had originated from Spain as translations of Arabic texts in the library of Toledo, a provincial capital in the Caliphate of Cordoba. Many of these had, in turn, passed through Syrian versions rather than being translated from the originals and these works were translated into Latin by a Scottish medieval scholar and mathematician Michael Scotus (1175-c. 1232).

Italian humanists showed their respect for classical learning by building up libraries of their own. In 1444 Cosimo de’ Medici founded a magnificent library, the first public library in Florence and followed, in 1445 by the construction of his Platonic Academy.

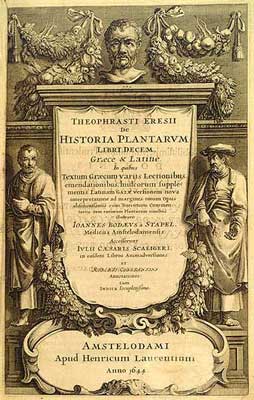

Theophrastus’s two works were, at the request of Pope Nicholas V, translated into Latin by Greek refugee Theodorus Gaza (c.1398-1475) who completed the task in 1454, the manuscript being circulated before publication in Treviso, Italy, in 1483.[38] Gaza had travelled to Italy before the fall of Constantinople to live under the rule of the Venician Republic. Gaza’s Latin translation was published by Bartolomeo Confalonieri (active as a printer between 1478 and 1483) in Trieste, near Venice, on 20 December 1483 and a copy is held in the library at Kew, its oldest printed book.[36] Another copy of the 1483 edition is held by the Smithsonian library in Washington D.C. now digitized and available to all from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Venice was an important publication and distribution centre for classical texts, especially Greek ones, from the earliest days of the printing press. Most later editions were published in the original Greek, such as that off the press of Aldus Manutius of Venice in 1497, although a Latin edition of all his remaining writings was published by Manutius in 1541.[29] In 1644 Johannes Bodaeus published in Amsterdam a folio edition of the two works with commentaries and woodcut illustrations.[35]

Our words ‘museum’, ‘lyceum’ and ‘academy’ all date from this time in history.[7]

Facade of the library at Ephesus reconstructed from materials on site and as it would have appeared in Roman times.

Roger Spencer – June 2014

Alexander

The young Prince Alexander (356–323 BCE) who left Aristotle’s charge at the youthful age of 16 was to become the great military commander Alexander the Great who, by the age of thirty, had established a vast Greek empire across the ancient world, conquering the Persians at Persepolis in the East in 330 BCE and marching as far as India to create an empire that stretched from western Greece to the Himalayas. He is regarded as one of the greatest military heroes of all time dying miserably in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon in 323 BCE when only 32, the cause of death unknown, possibly food poisoning or maybe murder. The charismatic Alexander was heterochromic, having eyes of different colours, one blue, one brown. In all probability he was bisexual. Married twice he nevertheless showed little interest in women. He was constantly in the company of general, and bodyguard Hephaestion, crying continuously for two days when Hephaestion died. While on his military campaigns Alexander did not forget his tutor Aristotle, returning living animals, plants and other trophies of war to the garden and zoo in Athens. The Lyceum garden grew many botanical treasures returned to Athens from not only Alexander’s military campaigns but also from merchant adventurers travelling in distant lands. Historian botanist William Stearn describes how it was Alexander who made the first recorded European contact with tropical vegetation as his army marched into Asia:Having defeated Darius [Persian king] in 331, Alexander marched his army into Turkistan (Bactria) and then in 327 invaded north-west India by way of the Khyber pass and entered the Punjab; the river Indus became the eastern boundary of his extended Asiatic empire.[17]Men like Alexander and his generals sent Theophrastus accounts of cotton plants, banyan, pepper, cinnamon, myrrh and frankincense.[13] Alexander always kept a copy of Aristotle’s edition of Homer’s Iliad nearby during his military exploits.[23] It seems that Alexander also showed his gratitude to Aristotle by making a philanthropic donation of 800 talents (modern equivalent of more than 4 million dollars) to the Lyceum in manner akin to a Macedonian National Science Foundation.[23] The two men died within a year of one-another. Both botanical and animal trophy collecting is known from well before these times but it is to this period that the origin of the modern botanical garden and zoo are often dated as we know beyond doubt that the Lyceum garden was a place of scientific study, research and education.[4] Alexander’s campaigns also had a great impact on horticulture. Grand villa estates built by his generals in Macedonia emulated the luxuriance of the gardens they had encountered while on their military campaignsin Persia. It was these Greek villas of the Hellenistic period that were later admired by the Romans and which inspired their villa gardens, notably those of the Roman emperors that were built on the Palatine Hill in Rome (see Greek gardens) in a tradition subsequently passing through Europe.

Theophrastus’s Botanical work

An early perspective of Theophrastus’s botany is given in Greene (1909) and in History of Botanical Science (1981) Alan Morton discusses Theophrastus’s two major botanical works: the Enquiry into Plants (Historia Plantarum) and Functions of Plants (Causae Plantarum) and the context in which they were written, as does Greene.[38]

Fronticepiece. Theophrastus’s Historia Plantarum

Illustrated edition of An Enquiry into Plants – 1644

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

We must consider the distinctive characters and the general nature of plants from the point of view of their morphology, their behaviour under external conditions, their mode of generation and the whole course of their life[26]Like Aristotle he grouped plants into “trees”, “undershrubs”, “shrubs” and “herbs” but he also made several other important botanical distinctions and observations. He noted that plants could be annuals, perennials and biennials, they were also either monocotyledons or dicotyledons and he also noticed the difference between determinate and indeterminate growth and details of floral structure including the degree of fusion of the petals, position of the ovary and more. He described some 550 plants in detail (including most of those previously listed in the Hippocratic Corpus and other possible sources), often including descriptions of habitat and geographic distribution, and he recognised some plant groups that can be recognised as modern-day plant families. Some of the names he used, like Crataegus, Daucus, and Asparagus are attributed to him. His botanical names listed in botanical works use the standard author abbreviation ‘Theophr.’ However this was definitely a work of botany ‘… not a local flora, a herbal or a treatise on agriculture.’[20] In describing plants he ‘ … spotted a whole series of characters which subsequently proved to be of high systematic value … he used in some cases, a simple, logical system of naming related species which can be said to have remained in scientific use for centuries until, adapted and improved by Linnaeus, it conquered the field in the form of the modern binomial. Significantly, rather than emphasising plant uses he makes a distinction between wild and cultivated plants and also avoided the contemporary practice of comparing plant parts to those of animals. On cultivated plants he agrees with Hippon that cultivated plants (cultivars) arose by man’s special care rather than divine intervention and … he had an inkling of the limits of culturally induced changes and the importance of genetic constitution. He pioneered questions concerning the relationship of plants to their environment and ‘ … may well be considered the founder of both plant geography and ecology – he not merely listed plants peculiar to particular countries and types of habitat, but shows awareness of plant communities and of the adaptation of specific plants to a range of environmental conditions.[10] The second work, Causae Plantarum (Reasons of Vegetable Growth) consists of six books (originally eight) discussing the growth, reproduction, and propagation of plants; the effect of environmental changes on the growth of plants; how various types of cultivation affect plants; propagation of cereals; artificial and unnatural influences on plants; plant disease and death; and the odour and taste of plants. In modern terms much of this work was on plant physiology. These works were not a local Flora or materia medica. Certainly of the approximately 550 plants discussed slightly more than half were plants found in agriculture, horticulture, or with some other practical use, but this did not make the books a study of economic botany. Together these books constitute the first text book on theoretical botany.[34]

Commentary

To some extent Theophrastus has been overshadowed by or even confused with Aristotle, but careful study of his works shows that in some important and essential ways he went beyond his teacher, and developed the theory and methods of science in a wholly materialistic and progressive direction

Morton, History of Botanical Science, 1981, p. 43

Theophrastus’s influence comes to us in several ways. Firstly he is an advocate for the world of Greek analytic thought that laid the foundations of Western science, setting out a manifesto for future plant science and, together with Aristotle, effectively launching the science of biology.[5] Theophrastus lived at a time when western civilization is generally regarded as having reached an intellectual peak. English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead summarised this view in his note (reduced here) that ‘ … the European philosophical tradition … consists of a series of footnotes to Plato’. And, as we have seen, Plato was by no means the only ancient Greek to have a great influence on the present day. Throughout history human interest in plants had been centred on utilitarian self-interest – the way they could be used as food, medicine, and materials. With Greek thought we encounter for the first time a curiosity about the plants themselves, how they resemble one-another in structure, how they grow and reproduce, and their ecology – the way that they interact with their surroundings.[37] It appears that the motivation for much of this, and indeed the other major achievements of this period, stemmed from pure intellectual curiosity, an ideal as historically precious as it is rare. This admirable non-anthropocentric agenda, the desire for knowledge for knowledge’s sake rather than for personal benefit or some practical utility, became an academic ideal. Through institutions like the Academy, Lyceum, the Museion, and the libraries at the Lyceum, Pergamon and Alexandria came the inspiration for the revival of classical learning that was part of the European Renaissance. From this period of history came the ideals of reason, logic, and science that prompted the creation of universities, inspiring both humanism and the Enlightenment. But there is just a small hop from the desire to ‘understand the world’ to the desire to ‘change the world’. There were inevitably practical or applied consequences for the scientific agenda of pure research, not least of which was economic botany. Theophrastus lived in a time when the independent Greek city-states were facing a possible imperial unification under a Macedonian monarchy. This would be a costly matter and every avenue for acquiring revenue needed investigation. As the son of a fuller Theophrastus was aware of the potential role for botany in such a major economic transition; it would involve:‘ … increasing the productivity of agriculture, the study of native and colonial plant resources, the acclimatisation of plants in new habitats, an intense interest in the production of timber and tar for shipbuilding, especially for the navy, linen for sails, charcoal for metallurgy and metal-working’[9]Theophrastus’s comment here comes to us as though written by a scientist on an Enlightenment voyage of scientific exploration. We hear similar words from Cook on his third voyage when on the look-out for the flax and pines needed by the British navy and it was the spirit of economic botany espoused by Banks as he created an imperial botanical hub at Kew Gardens in London. The parallels run deeper. Joseph Banks was an Enlightenment English gentleman in the Greek tradition. As a young man he had attended the best academies available, those following the Greek model and with a classical curriculum. He owned a large country estate with an income thataenabled him to indulge his interest in natural history. His world of interests and peers consisted almost exclusively of men. His own wife is portrayed in the literature as being non-intrusive while maintaining domestic stability. On all his travels he took domestic servants including musical entertainers. Travelling with him on the Endeavour were four personal servants, two of them negroes, along with two greyhounds. His dress was often flamboyant distinguishing him from the crew. Though he had deliberately refused the classical education expected of a gentlemen with his background, his heroic voyage on the Endeavour bore a remarkable resemblance to the epic adventures of Greek mythology, the search for the Golden Fleece of Jason and the Argonauts, and Homer’s epic the Odyssey complete with the sirens and lotus-eaters of Tahiti. As a man of considerable means he could afford the very latest in scientific equipment and an extensive library. Banks led life like a Greek hero. Although the settlement of Australia was a practical matter of redistributing people from Britain to a new continent, to Joseph Banks as a key Enlightenment figure it was, or at least very rapidly became, an economic matter to do with a burgeoning British Empire and the way that plants could contribute to a new economic order. The parallels with Theophrastus are uncanny. In Philip Miller, Joseph Banks, the Chelsea Physic garden, and Kew Botanic Gardens we see a parallel with Theophrastus, Alexander and the garden at the Lyceum: history repeating itself under similar circumstances and, surely, no coincidence. In spite of earlier historical examples, the menagerie and educational plant collection at the Lyceum that were so strongly supported by the scientifically-aware military collector Alexander are justifiably regarded as major precursors of the physic gardens and later botanic gardens and zoos of the Renaissance. We see here the beginnings of a tradition of international redistribution of plants and animals that has subsequently gained momentum. Banks was to make Australia one of Britain’s many sources of plants while, in turn, the Australian landscape would be transformed by the temperate crops and agriculture that defined the British countryside. But it is for his plant science that Theophrastus is best known. In his two works on plants ‘Almost every aspect of modern botany is at least indicated – morphology, anatomy, systematics, physiology, ecology, pharmacognosy, agricultural and applied botany, plant pathology … presented in a way that would not be matched for another eighteen centuries [8] Plants would remain objects of medicine until the Italian Renaissance when, following the fall of Constantinople in 1453, many Greek intellectuals fled to Italy which was at this time the centre of European culture, commerce and industry, reviving the ancient classical texts that fuelled this new phase of learning. Italian Luca Ghini (c. 1490-1556), professor of botany at Bologna from 1534 was called to the University of Pisa Botanic Garden where between 1545 and 1550 he renewed contact with descriptive botany, even though botanic gardens at this time still resembled the earlier ‘herbularis’ or physic gardens of the medieval European monasteries. One of his students, who later worked in Padua, was a priest called Michele Merini (fl. 1545) and it was he who established what is considered the first ‘herbarium’ of pressed and dried plants, 201 of these still preserved today in Florence, although the art of plant-pressing probably dates back to Ghini or maybe before. The historical record indicates Luca Ghini as probably giving the first scientific course in plant taxonomy (as distinct from instruction on medicinal herbs) since the time of the ancient Greek schools that were based on the lectures in botanical science given by Theophrastus.[19] Theophrastus maintained an independent mind. He expressed dissatisfaction with Aristotle’s universal application of teleological (that is, goal-directed) explanations (see article Meaning & purpose) and is also known to have composed a large compendium of the doctrines of previous philosophers, which itself is lost, but which probably formed the basis for much of the later analysis of pre-Socratic philosophy.[18] Tellingly, in recognising his debt to predecessors Darwin wrote ‘Linnaeus and Cuvier have been my two gods, though in very different ways; but they were mere schoolboys to old Aristotle’. Like Aristotle, Theophrastus accepted the stability of the classes of society and projected this into biology ‘ … where evolution was replaced by the conception of a scale of nature, a hierarchy of natural classes or kingdoms.’ This assumption of a ‘natural order’, stated so powerfully by both Plato and Aristotle has, to this day, exerted a powerful hold on human understanding of the structure of both human society and nature (see Grand narratives – The Great Chain of Being). Historian Morton draws attention to the scientific approach emanating from Ionia and just one inadequacy in the Greek approach, the lack of experimentation, which he puts down to the social stigma that in Greek society was associated with manual work. It was the great Carl Linnaeus who gave Theophrastus the sobriquet ‘Father of Botany’ for it was from him that Linnaeus undoubtedly obtained ideas, not only about plant taxonomy, but on subjects like plant collection on foreign soil, acclimatisation, and economic botany – ideas that he would, in turn, pass on to his ‘apostles’ (see Linnaeus) and which would also be taken up by people like the highly influential Joseph Banks.

Key points

- Theophrastus was part of a Greek culture that was part of the world-wide introspection of the Axial Age

- Greek analytic thinking provided the foundations of Western philosophy, law, language, literature, politics, and economics as well as medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and science in general including less well-known contributions in subjects like religion and sport

- Theophrastus was the founder of analytic plant science which examined the plants themselves, their classification, structure, function, reproduction, relationship to the land, and geographic distribution as well as their various uses. He recorded plant names and terminology that would last for about 2000 years, his work underlying much of that often attributed to Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides

- The botany of Theophrastus and zoology of Aristotle represent the climax of natural history in antiquity

- Theophrastus inherited Aristotle’s garden (possibly donated by Demetrios of Phaleron) and plant collection at the Lyceum, some plants collected in foreign lands. The living collection was used by him for botanical instruction and, though similar gardens had been developed elsewhere in the ancient world, this one probably has the most direct claim as a forerunner of the modern botanic garrden

- Theophrastus observed the changes that can occur to plants when under human care and selection, while hinting at almost every aspect of modern botany including what we might today call genetic and phenotypic variation

- In the gymnasia of ancient Greece we see the origin of the modern university

- Libraries in Greece were among the earliest stores of knowledge being also places of learning and research

- Alexander was the first ‘Westerner’ to observe tropical vegetation; encouraged the distribution of plants and animals by sending back specimens from his military campaigns

- Though plant and animal trophies had been collected from distant lands in former times, those sent to Greece likely stimulated the later establishment and goals of zoos and botanic gardens

- Greek thinking influenced social behaviour and the attitudes to plants of the early Australian settlers

- Persian gardens seen by Alexander and his generals inspired the creation of luxurious gardens that were later emulated and developed by wealthy Romans who passed on gardening traditions to Britain during the Roman occupation

- Theophrastus’s description of the social value of plants for economic botany was likely emulated by later botanists like Carl Linnaeus and Joseph Banks, playing an important role in empire

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019 . . . 3 May 2023 revision

Excavation of the Lyceum where Aristotle taught, his position as Head being later taken up by his friend Theophrastus, the ‘Father of Botany’ and founder of plant science Photo: Roger Spencer, 16 June 2014

Artist’s impression of Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE) Sculpture in the Orto Botanico Palermo. Adapted from Wikipedia Commons