Time

Floral Clock

The word ‘time’ has many meanings

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

This series of articles on ‘time’ is a major diversion from the site’s principle themes. It has little to do with plants (except perhaps the floral clock above). I must admit I wonder where I found the time to do this thinking – and indeed the sanity of undertaking it in the first place. However, I have included it because it was my philosophically-untrained attempt to addresses those elements of the world that frame our entire existence – space and time – which still challenge our best philosophy and science. Its questions are relevant to all scientific disciplines and have tweaked the natural curiosity of all of us at one time or another.

Space and time are the stage on which all our experience is acted out.

Physics has made great headway in understanding the measurement of time but many questions remain. Philosopher Immanuel Kant insisted that these are forms of mental representation that we must presuppose in order to have any experience at all: they are the form of all perception. So, for Kant, space and time are not assumed to be necessarily objects or properties of the external world, but the preconditions for perception itself. They are therefore a priori and necessary. He therefore challenges us to question the degree to which space and time are mental constructs rather that properties of the world. That science, through general relativity, has fused our intuitive understanding of space and time into a single category space-time, and quantum mechanics has given equal value to past and future, suggests that his challenge was well founded.

Mostly I have included this discussion because even a cursory examination of the topic warns us to expect problems that extend well beyond relativity and quantum mechanics into language games, biology, neuroscience, the difference between subjective and objective evidence, and much more.[6]

Coming to grips with time is a multidisciplinary study.

Biology

The physics of relativity tells us that us that time exists objectively in the universe itself. Identical clocks carried in two aeroplanes, one of which does a circuit of the earth, will tell different times, as will atomic clocks situated as little as 50 cm difference from the centre of the earth. The differences in these two cases can be calculated with great precision and confirmed in practice (even though the differences are ridiculously small). So, on this understanding, time is not some subjective quirk of our minds, something created by our intuition or imagination, it is part of the fabric of the universe. But there are undoubtedly subjective sides to time that need explanation, most notably the way it seems to ‘flow’ and therefore have ‘direction’. But also because we also seem to exist in a ‘now’, that is difficult to define. Relativity drives us to the conclusion that past, present, and future are a matter of perspective, not something universal. And yet we experience time in some way in our minds (we have no (explicit) dedicated sensory organ for time). It is this perception of time in our brains that is now being subjected to scientific investigation. Our minds begin with the ordering of events and their causality (much of philosophical interest here). In other words we have experience episodic memories and sequences. Research suggests that our experience of the ‘what, where, when’ – of space and time – occurs in the lateral and medial entorhinal cortex that send signals into the hippocampus and that representations of space and time are generated by the same regions of the brain. The most obviously subjective aspect of time is the way time passes slowly when we are bored and quickly when we are engaged. This difference has been detected by MRI studies in the neural insular cortex. So, the relation between experienced time and physical time in the world is perhaps our greatest puzzle. Experienced time is undoubtedly our evolutionarily developed user-friendly biological app, helping us to cope with the world. Under relativity theory there is no objective ‘now’ so we need a biological account of why it evolved. Clearly time is a multifaceted concept. We cannot simply pose the question ‘What is time?‘ and expect a neat summation. We must begin by defining our terms, by investigating the place of ‘time’ in the language. This semantic analysis will, hopefully, clear away unnecessary conceptual clutter making way for the serious questions.Language

The conceptual analysis of time must begin with an investigation of the time-talk that is riddled with semantic nuance and metaphor. To establish a starting point we must first isolate the many strands in the rope of temporal semantics which will, at the same time, give us a view of the overall temporal landscape.Semantics

‘The meaning of a word is its use‘ is a valuable maxim because it reminds us that we cannot impose our semantic prejudices on other people – unless we do so by providing explicit definitions. The meaning of a word is not what I think it should be, it is what others determine it to be. Some words have simple and distinct meanings defined in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions: they have no ambiguity. For example: gold is a metal with the atomic number 79. Such words with discrete meanings are in the minority. Most word meanings are linked to the meanings of other words in a web-like way, or like the fibres of a rope. ‘Time’ is in the latter group, having many nuanced senses and associations and consisting, in effect, of a collection of meanings that share a family resemblance.Polysemy

In casual conversation there is no need to ensure clarity by constantly defining the terms we use – this is too tedious, so we dont bother: we jump right in and grasp the semantic hints given to us in discussion, assuming that clarity will emerge as we proceed. But where precision is needed, clarity is required. And when words have multiple meanings, a flood of polysemy, then we can quickly drown in deep semantic waters. To explore what we mean by ‘time’ then we must unravel the threads of meaning that collectively give rise to a family resemblance. And in trying to answer the question ‘What is time?’, a dictionary is a good place to start the hunt through language.Dictionary definition

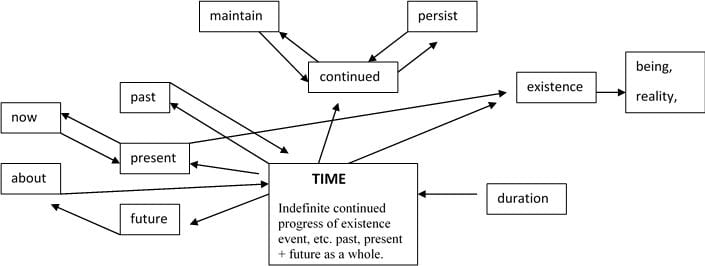

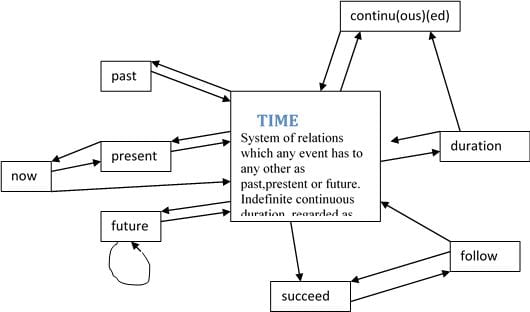

Dictionary definitions of ‘time’ can be used to establish a set of time-related words (see diagram). The diagrams below show some of the semantic relationships between these words.

Concise Oxford Dictionary – 1964

Paths between major senses of the word ‘time’ Arrows pointing both ways indicate circularity

Image – Roger Spencer

Macquarie Dictionary – 1984

Paths between major senses of the word ‘time’ Arrows pointing both ways indicate circularity

Image – Roger SpencerUnpacking the semantics of ‘time’

The word ‘time’ is the most frequently used noun in the English language with other temporal words like ‘day’ and ’year’ ranking in the top ten. To avoid discussions proceeding at cross-purposes we must, at the outset, isolate the major meanings of ‘time’.

Here are just a few nuances of meaning (senses) that occur in everyday language:

• time as now, or as a stated time (What time is it? 3 o’clock.)

• time as duration (How much time was needed? It took an hour.)

• time as orientation (The space ship traveled backwards in time.)

• time as an affect (We all had a good time.)

• time as movement (The older you get, the faster time flies.)

• time as agency when used as a verb (I will time the race.)

• time expressing multiplication (Three times four.)

• time as a prison sentence (He is doing time.)

• time as tense – past, present (now) and future – expressed through the tenses will be, is and was (At some future time . . . etc.)

• time as tenseless sequence or date – the ordering sequence ‘before’, ‘simultaneous with’ and ‘after’

The Australian Pocket Oxford Dictionary 4th edn lists 20 senses of ‘time’.

For our purposes it is enough to note that the semantically rich word ‘time’ denotes a wide range of concepts with a ragged family resemblance. The task now is to isolate those meanings that are of philosophical or scientific interest and look more closely at how they are interrelated.

A full justification for the following taxonomy of time and the relationship between its contents will emerge in later discussion. For the time being, the different senses will be coded and defined. Then, in any given sentence, it should be possible to indicate, with the code, the particular sense of ‘time’ that is being used.

A semantic taxonomy of ‘time’

To simplify the discussion it is now time to apply some definitions (indicated by the letters DF).These definitions are not intended to be strict or formal, they are not stipulative definitions but they approximate everyday usage. They are place-markers that will serve their purpose, even in this loose form. This is a classification that helps clarify the various senses in which we use the word time but there is semantic intergrading. Each of the various meanings is now given an abbreviation so, for example, ‘duration’ is indicated as T(d):

Duration series, T(d)

Time as an interval, quantity or ‘duration’, is used in two major senses:

Time (restricted duration), T(rd)

This is duration in a restricted sense as DF a temporal interval: a period of lapsed or lapsing time.

For example:

“He spoke for a short time” (lapsed time)

“The recession lasted for three years” (lapsed time)

“My birthday is getting closer” (lapsing time)

Time (unrestricted duration) T(ud)

This is duration in an unrestricted sense as DF continued existence.

For example:

“Everything exists in time”

“Time, like an ever-flowing stream, bears all its sons away”

Succession series

Time is generally perceived and characterized as change that follows a definite order of succession expressed in the sequential relations ‘earlier than’, ‘simultaneous with’, and ‘later than’. Many philosophers believe this relation to be our most basic understanding of temporality. This order of temporal relations, which tells us when things happen, is treated in two very different and important ways. Either relations are targeted on the present (now), which we can call time (change) or T(c) or on one-another, which we can call time (permanence) or T(p). The language of these succession series does not always use the word ‘time’ itself, but time is implicit in its use.Time (change), T(c)

This category encompasses what Cambridge philosopher John McTaggart referred to as the A-series, a temporal ordering which, he believed, encompassed real change. This is the language of temporal becoming with its associations of movement, flow and passage, its dynamism coming from statements (and events) that pivot around an ever-changing present (now). The sense of movement derives from the feeling of transition from future, to present, to past (temporal passage).What things may have these relations?

Well, we may distinguish what can be called the A-scale of times (which includes moments or particular durations (intervals)), and the A-series of events (taken to include facts, people and things). The significance of the distinction between times and events will become apparent later. In everyday language present events and A-times can be of any duration.

Being past, present or future are properties of tensed facts. The language we employ for this form of time uses not only the words past, present or future but also the grammatical tenses was = past, is = present and will be = future. But note that statements are also philosophically tensed if they can be placed in past, present or future in relation to the present (now) by words (temporal indicators) like yesterday, soon, now, or next week. In other words something may be philosophically tensed without using tensed verbs.

A philosophical tense is therefore a position in the time T(c) series (of past, present (now), future) defined by its location (and often duration) from the present (now).

For example:

“It is raining” rain simultaneous with the present (now)

“The party was yesterday” party one day earlier than the present (now)

“The next party is in three days” party three days later than the present (now)

“It is time for a cup of tea” cup of tea simultaneous with the present (now)

“The time is now 3 o’clock” clock time simultaneous with the present (now)

“I’ll see you soon” seeing you slightly later than the present (now)

“It is 4 pm” 4 pm simultaneous with the present (now)

Statements made using T(c) have truth values that also change. For example, “My birthday is in three days time” will change in truth-value as time lapses. The truth-value of statements made using such temporal indicators will therefore depend on the time (context) of their utterance and are thus said to be indexical, or token-reflexive.

T(c) is sometimes referred to as having temporal properties because it deals with things having the properties past, present and future. This contrasts with the temporal relations of T(p). However, T(c) is also relational but the temporal relations target the relations of the tenses to the present (now) rather than one-another.

T(c) indicates when in relation to the present (now) cf. T(p). Because T(c) involves change it is often referred to as a world of Becoming.

Time (permanence), T(p)

This category encompasses what McTaggart referred to as the B-series, a static temporal ordering in which DF statements of the relations earlier than, simultaneous with, and later than are made in relation to each other not in relation to ‘now’. McTaggart claimed that this series does not encompass real change. As before, there is a B-scale of times and a B-series of events.Statements about time T(p) have truth-values that remain the same. Because the present (now) is irrelevant to this series, there is no need for language that uses tense; statements using the B-scale and B-series are tenseless statements. This is the impersonal, timeless and tenseless language expressing the changeless truths of maths, logic and some philosophy.

A date is a position in the T(p) series defined by its location (and often duration) from other events.

McTaggart’s B-series is said to be static because the dates of events and times do not change. The B-scale times and B-series events of time T(p) do not appear to move, only the present (now) of time T(c) seems to move.

The date of an event is related by its duration to another event and this date never changes because the duration between the two events never changes. For example “My 50th birthday occurred before my 25th wedding anniversary” if true, will always be true. The year 2001 is a date because it (unchangingly, that is truly) relates to the year 1.

Other examples:

“It rains on January 26 2001.” rain simultaneous with January 26 2001

“The party was on the same day as her birthday.” party simultaneous with birthday (also tensed)

“The Christmas party is on the last day of term.” next party later than this party

“The eclipse is in 2010” eclipse simultaneous with 2010

“Before tea” something earlier than tea

“Tea is served at 4 pm” tea simultaneous with clock reading 4 pm

B-times are not defined by how much earlier or later they are than the present but how much earlier or later than each other. The year 2001 includes all those events occurring between 2001 and 2002 years after Christ’s birth.

T(p) is treated as static or permanent because, T(c) there is no temporal movement or passage, and the relations between the times and events are unchanging as are the truth-values of statements about the series.

T(p) indicates when in relation to other events cf. T(c). Because T(p) does not entail change it is often referred to as the world of Being.

Similarities of T(c) and T(p) time-scales:

• Defined by the same temporal relations (earlier/simultaneous/later)

• Put events in the same order

• Measure time in the same way as durations or moments

• They are isomorphic (if a B moment is present, the times on one scale has counterparts on the other – if it is now (A-time) 2020 (B-time) then next year which is 1 year away (A-time) is 2021 (B-time))

Differences between the T(c) and T(p) time-scales:

• A B-time is a position in time defined by its relations to another time or event; an A-time is a position in time defined by its relations to the present (now)

• Durations of the B-scale remain the same; those of the A-scale are constantly changing, increasing into the past and decreasing into the future

• Statements about time (p) have truth-values that remain the same; those of the A-scale change.

Object and relation

Most sentences use the word “time” either in the sense of an object – that is, something having an existence independent of other objects and events – or as a relation between objects or events. This usage is critical to our basic understanding of time, as there is the implication that time is either absolute or relational. In discussing time it is extremely difficult not to write or speak about it as though it is distinct from other things, even if this is not the intention.Time as an object, T(a)

This is the prevailing use of the word “time” as a moment, instant, or substrate to existence that is separate from other things. It infers absolute time by treating time DF as an object existing independently of other things. The strength of this temporal separation from other things as expressed in various sentences seems to be a matter of degree.For example:

“I will be with you in a moment” (cf. I will be with you in 5 minutes)

“The events were separated by time intervals of one minute” (cf. the events were one minute apart)

“The events occurred at the same moment in time” (cf. the events were simultaneous)

“Everything exists in time” (cf. everything there is, exists)

Time as a relation, T(r)

This is identical with the time (p) category??? which treats time as DF a relation between times or events that does not imply time as something separate from the things themselves.“My 50th birthday is before my 25th wedding anniversary”

“The year 2001”

Time as a name, T(n)

We often refer to time in a generic way as a kind of name DF using the word “time” as a name.For example:

“I am studying the philosophy of time”

“Is it possible to give a definition of time?”

Time of physics, T(*)

Occasionally the word ‘time’ is used to indicate scientific or physical time (space-time). This is a sense not quite covered by those already given.For example:

“According to Relativity, time is an aspect of the universe”

Time as now, T(now)

This is objective time, the physical boundary between determinacy and indeterminacy, which we experience as the specious present: sometimes also called the present moment or, more imprecisely, the present.Time & metaphor

Included in the many senses of the word ‘time’ must be the way that we try to overcome its abstraction by using metaphor. Metaphor is ‘as if’ talk. Language needs to be simple and practical if we are to interact effectively with the world. However, many aspects of the world are complex and abstract. We cope with this by using ‘as if’ metaphorical language that renders these difficult ideas in everyday terms. For example, ordinary language is like a physics toolbox. Nouns provide us with objects or substances to work on, verbs provide us with causation as agents act on objects, pronouns locate all this in space, and verb tenses place it in time.This mental and linguistic physics toolbox allows us to live without constant doubt and confusion. But metaphor does not always deal well with abstract ideas. The language of space and time are riddled with metaphor and this is one reason why the idea of time is so confusing. So, for example, we ‘keep time‘, ‘tell time‘, and ‘pass through time‘, ‘save time‘, ‘spend time‘, and ‘waste time‘. If we break the law we might ‘do time‘. Time ‘flows‘ and ‘unfolds‘, sometimes we are ‘carried along with time‘ or perhaps ‘time passes us by‘ and maybe, just occasionally, ‘time stands still‘. We understand space better than time and, since these two ideas seem so closely related, we frequently describe time using the metaphor of space, as in: ‘My birthday is getting closer‘, ‘In the distant future’,, ‘It has been a long time coming‘ . . . even equating time directly to space ‘It all happened in a short space of time‘.

The important point about metaphor is that it allows us to make inferences by giving us a framework for our reasoning, a framework grounded in the familiar and everyday. If time is really like space then we know that something can really be temporally close or distant.

What are we to make of all this metaphor? Put simply, metaphor can help or hinder – but we cannot always tell which of these outcomes is winning. We just need to be aware that metaphors allow us to use reason from one domain of knowledge to that of another. We resort to the use of metaphor as a lever in the construction of inferences (see Science communication). This is fine provided it is legitimate to make such inferences but we need to be vigilant whenever we see a metaphor, and to use the best ones as they can be contradictory, and we are prone to accepting metaphor as reality since the difference between metaphor and reality may be obscure.

So, much of the mystery and puzzlement associated with time can be attributed to the assumptions carried mischievously hidden in the language we use to describe it. Firstly there is the problem of polysemy, the word ‘time’ having many many meanings. This accounts for some of time’s paradoxes, puzzles, and conundrums since we can easily find ourselves talking at cross purposes.

Here are some of the many ways time and metaphor merge.

Time-as-object talk (time is an object) – T(a)

The most frequent confusion in the language of time is to unwittingly treat it as an object. If we think time really is an object that is fine but we need to be aware of what we are doing when we say ‘Time is flying by’ or ‘Set aside a block of time’.So, talk about time often proceeds with an assumption of T(a). Time treated as an object in this way (T(a)) gratuitously gives it an independent existence, like a substance or container in which events happen (see also hypostasis-speak). This possibly a product of our metaphorical mode of thought.

If you are a Relationalist referring to time, T(r), then expressions such as ‘the events occurred at the same moment in time’ and ‘the events were separated in time by one minute’ and ‘an interval of time’ imply time (a) and are distinctly misleading. Replacing these expressions with phrases such as ‘the events occurred together’ and ‘the events were one minute apart’, ‘a time interval’ is much more conducive to time (r).

It may, of course, be argued that time (a) is not necessarily implied by the use of objectifying language. Be that as it may, avoidance of such talk goes a long way to clearing the field for the Relationalist.

Examples like this are blatant: but at other times the role that language is playing is more subtle. Would ‘everything exists in time’ be acceptable to both views, and if not, how could it be rephrased? ‘In time’, ‘through time’ and ‘time itself’ are all problematic.

All uses of the word ‘time’ need to be scrutinized to see whether they imply that time is an object or a relation (and similarly for events?)

Space-time-talk

In everyday language we speak of space and time as though they are discrete. If we follow the physicists into space-time then we must concede that they are similar and intertwined. One way of remembering this interrelationship is that, in the universe, the faster you travel, the more slowly time passes. Nevertheless, we speak of duration and extension/expansion as qualitatively different. Thus a length of time is not the same as a length of space, even though we refer to lengths in both cases. There are many cross-referencing words like this including ‘gap’, ‘interval’ and ‘position’ but the analogy of space and time is pressed when we speak of a ‘long time’ or, at its extreme, a ‘space of time’. In summary, we must be aware of temporalizing space, and spatializing time. Movement (passage) of time is not (quite) the same as movement in/of space!Stanford psychologist Lera Boroditsky has researched the human mental representation of time in terms of spatial metaphor and representation. Her work has shown that although spatial metaphor is universal there is considerable variation between cultures and social groups in the way this metaphor is expressed. Time is regarded as stationary or moving with people and events stationary or moving in relation to it, it is infinite or bounded, expressed as distance or quantity (English speakers mostly use distance – ‘A long time’, while Greek speakers use quantity – ‘Much time’), orientated horizontally or vertically, left to right, right to left, front to back, back to front, or along geographic coordinates (east-west). The way time is conceptualised is strongly related to the way particular languages treat time, the particular metaphors used, and the orientation of the written language (Arabic and Hebrew languages orientate time from right to left). English speakers tend to use horizontal metaphors, mandarin speakers vertical ones. The Australian Pormpuraaw languages orientate time by absolute direction (compass points).[1]

Once again the obvious cases are straightforward but there are many subtle problems to contend with as time becomes space-like and space becomes time-like. Can time have a ‘direction’, this seems a spatial term that would operate better with a temporal word. We often speak of time as ‘linear’ but although this word might feel right it does not make temporal sense. When language is teased out is may well be that a concept of space-time underlies the categories we refer to in isolation as ‘space’ and ‘time’.

Time & motion talk (time is motion)

Science, mathematics, logic and many philosophers claim that ‘becoming’ (with its past, present, future and transitive ‘now’ as expressed through the tenses ‘is’, ‘was’ and ‘will be’, confuses the true representation of reality which is tenseless. That is, the dependence on tenses is a human construct with no foundation in reality.Although this view is contentious it is the preferred approach of the above disciplines, which either ignore tense or use the present tense as a kind of a temporal language. Needless to say our language follows the way we ‘feel’ that the world is.

The context of motion and time generally involves four items: an observer, motion, objects, and locations (?times?). Motion suggests two options: either time is moving and the observer and objects are still, which involves language of the kind ‘Christmas is getting near’, ‘Time is passing’, or the observer is moving and time is still, which involves language of the kind ‘We’re getting closer to Christmas’. In both cases the metaphorical aspect of the language is challenged when we ask about the speed of this motion, although we do say ‘Time seems to go faster every day’. The situation is further complicated by blatantly treating time as an object in motion like a bird as in ‘Time flies by’ (three metaphors together time as a bird, time as object, time as motion).

Hypertime-talk (time is motion at a particular speed)

We cannot, without qualification, speak of time moving because it begs the question ‘How fast does time move?’ a question requiring the postulation of another time to measure the original time: that is, a hypertime, which would in turn move at a certain rate – leading us into an infinite regress.This might seem like an obvious slip, but ‘moving’ time (a form of space-time talk) can creep insidiously into all kinds of discussion and is entrenched in everyday language.

Hypostasis-talk (events are motion in time)

We have already seen hypostasis in operation through the substantiation of time. In a similar way it is a simple matter to confuse events (or properties) with substances. We can infer, for example, that events move or change which is clearly not the case. Though this might appear an obvious error it is one that is easily made and often difficult to detect. It is not unusual to find assertions that events (which are changes) are changing themselves, which is plainly absurd.Matter, time, and space talk

Although we might not be sure of our philosophical position on time, we should always be aware of the implications of what we are saying and always be alert to the way we all tend to align our words with what we assume is ‘reality’. Space, time and matter give us ample opportunity to confuse concepts. Through our language we almost invariably treat them as separate. But if we are to believe relativity, then matter, space and time are inextricably linked rather than being separate things.This is just one of many examples of science becoming more concerned with relations and less concerned with objects. We may not be able to account for this effectively in the way we use language but it helps to be aware of its implications.

Discrete-talk (time is discrete units)

We speak of time using the language of discrete units – as moments, hours, days – when physically it is generally portrayed as being continuous. If we treat time like number, or as being additive, then we incur all the problems of cardinality (counting). That is, problems of infinities, numerical systems, relations of addition and subtraction, discreteness vs continuity (density) and more. Discrete-speak is necessary for communication but it is theoretically loaded.Time semantic-talk

From the analysis of the semantics of time it is clearly necessary to be aware of the various senses in which we may find ourselves speaking of time, mostly the three different modes of time: as duration; as past, present, future; and as ‘now’.Possible-world talk (past and future as places)

If we believe, with the presentist, that everything happens in the present, then there is a form of everyday language that is confusing. It is the way we speak of the past and future as though they are existing worlds. For example, we say “I will make the sandwiches tomorrow”, “I will do better in the future”. This kind of everyday language is harmless except that it creates the impression that there is a kind of world in the past or future that we “move into” or “move out of” as we go along. Whereas, in fact, we are always in the present, the future and tomorrow never come. To be pedantically logical we should say something like “I will make the sandwiches tomorrow, in the present”, “I will do better in the present of the future”.Spatialization talk (time is space)

Probably the most obvious way we use metaphor in everyday language is in the use of spatial terms: we describe time in the terms of space. So we say ‘It was a long time’. ‘In the distant future’, ‘For a short period’, ‘A length of time’ and, best of all, ‘A large space of time’.

Direction talk (succession as direction)

We constantly speak of the ‘direction’ of time: we look ‘forward’ to holidays and we look ‘back’ at a mistake. On reflection this is clearly spatial metaphor. Time does not go forward and back any more than it goes up or down, left or right, sideways, north, or south. Everyday language is unlikely to change but awareness of this apparent metaphor can help us think more critically about time.Key points

Because time is abstract, the language we use to describe it is rich in metaphor. And since space and time (treated as separate entities in everyday language) share many properties, then this metaphor is often used to spatialize time, and temporalize space. The danger of metaphor is that we can use it to make false inferences, and treat it as ‘reality’. All-in-all metaphors can create logical contradictions and confusions that all contribute to the clouding of our idea of time and do not help us to think scientifically. Already it is clear that part of the mystery of time lies in polysemy (its many meanings) – that when we talk of ‘time’ we are referring to many different things, so it is not surprising that, taken at face value, time is a concept that is likely to confuse. We are now in a position to draw a distinction between at least nine major strands of meaning in the semantic cloud of ‘time’, each with its own set of semantic relations. These temporal categories can be listed with their codes as follows – they will be examined and explained in more detail in subsequent articles:Time (restricted duration) = T(rd) sub-divided into fixed intervals T(rd,fi), flexible intervals T(rd,fl) Time (unrestricted duration) = T(ud) Time (change) = T(c) which may be represented as a time T(ct) or as an event T(ce) Time (permanence) = T(p) Time (absolute) = T(a) Time (relational) = T(r) Time (general name) = T(n) Time (physical time, space-time)= T(*) Time (now) = T(now)

+ = semantic independence <> = semantic overlap Semantic and metaphorical analysis alone has given us considerable insight into the many ways that language contributes to a muddled idea of time, but it has not helped us answer the more direct questions about the nature of time. Is time an object? Does it really move in some temporal sense? Is time a relation between things rather than an independent object of the universe? There is also the complex semantic web we use to describe its many-sided character. For the philosopher, coming to grips with time is in large part a process of clarifying the language and concepts we use to explain, describe and interact with it. After all, it is clear from the four simple definitions of time given above that one reason why time is frequently characterised as deeply mysterious is because it means different things to different people. Relativity theory tells us that there is no such thing as time by itself, but rather space-time. What consequences would there be if we tried to tidy up our everyday language by using the word “space-time” instead of the word “time”? Would it make sense to do this? How are the various time words conceptually related? We often use the words “time” and “duration” interchangeably – but do they mean the same thing? Are there occasions when it is clearly preferable to use one of these words rather than the other? It can hardly be doubted that differences in meaning between these and other interrelated time words can cause confusion. Is it possible to cut through these semantic difficulties and expose the metaphysical reality of time remembering that w can only communicate about time through language? When we think of physical time it seems primitive; that is, an ultimate feature of the universe that cannot be reduced to something more simple or fundamental. We might consider space and time are ultimate irrationals of the universe whose presence is irrefutable but whose understanding is forever beyond our (direct) grasp. Does time really exist in any sense at all other than in our minds? The following articles will look more closely at this question. All the difficulties and puzzles we associate with time are interwoven in such a complex way that it is difficult to follow one particular thread of thinking from beginning to end. To help achieve this I have tried to cover many aspects by asking specific questions as follows: How does language influence our understanding of time? Is time a physical object? In what sense does time flow? Two observations can immediately be made about time. Firstly, as a word that is semantically extremely rich with many nuances of meaning we can anticipate ambiguity. Secondly time, being an abstract phenomenon, we can also anticipate the liberal use of metaphor to provide concrete examples of the way we can make inferences about time and its properties (see Scientific communication). If we are to make sense of time then we must surely begin by analyzing the words and language that we use to describe and understand it: there is no alternative but to tease out the various ideas, doing our best to understand how they are connected and it what way. To do this will require a conceptual and semantic analysis and this will be the topic of this first article. Intuitions must be the second topic to tackle because when doubt sets in it is to our intuitions that we look for support: we need to know as sooon as possible how strong this fall-back position is. What aspects of time are subjective, a consequence of our uniquely human perspective, or a matter of psychological projection? This topic is developed in Time 3 – Flow. Aristotle defined time as ‘the number of movement in respect of ‘before’ and ‘after’”. Later, Plotinus pointed out that time is not a number, time is what is being numbered. Similarly, ‘before’ and ‘after’ in the sense in which Aristotle meant them were clearly not spatially before and after one-another, they were temporally before and after one-another i.e. ‘before’ and ‘after’ in time. So, Plotinus argued, on both counts Aristotle was providing a circular definition by defining time in terms of itself. This line of argument can be applied to other definitions. We might say, time is not succession itself, but succession in time. Time is often defined in terms of change, but as soon as we examine the notion of change we are driven to talk about time, so perhaps time and change are, in fact, same thing? When we think of time in this way we may be thinking of it as ‘duration’ – which dictionaries describe in either an unrestricted sense as ‘continued existence’ or in a restricted sense as a ‘measured or measurable interval’. However, in day-to-day language time is a rich and complex concept with so many nuances of meaning that any short definition would be totally inadequate!A philosophy of time

This article began with the observation that ‘time’, as represented in everyday language, is not just one thing, but many – a tangle of metaphor and multiple meaning. Nevertheless a simple distinction may be made between subjective aspects of time as limitations imposed by our species-specific biology – our sense of time’s flow, direction, and orientation to ‘now’ – and the objective time as revealed by physics. Already we are beginning to grasp some of the problems that can arise when asking the question ‘What is time?’ which demands a further question in reply . . . ‘Which time are you asking about?’ The drawing together of thoughts in this introductory article is intended as an incentive to read the more detailed argumentation developed in later articles. In the Epilogue to his ‘A Brief History of the Philosophy of Time’ (2013) Adrian Bardon draws together the threads of contemporary thinking on time. From the temporal idealists we have learned important lessons about both time and science itself. Our metaphysics, our sense of reality, is mind-dependent. The only way we can understand the world outside our minds is through the mediation of our minds. The efficacy of our mental representations is measured in terms of their explanatory power, simplicity, and application, not through a direct knowledge of nature itself. This does not cast us into a world of subjective uncertainty. We have every reason to believe that the mapping of our scientific explanations onto the world, our representations of the world, are becoming increasingly commensurate with what there is. Our direct experience of the world is what has proved of adaptive value to our species Homo sapiens. As conscious living organisms we are both deeply aware of and totally dependent on the spatial ‘here’ and temporal ‘now’. No doubt there is more to be gleaned about this from phenomenology and evolutionary psychology even if scientifically and philosophically we are persuaded by the early twentieth century philosophical and scientific work of McTaggart and Einstein that there is no special privileged and moving ‘now’. The ultimate constituents of the universe may be continuous, or discrete – both or neither – we do not know. It is scientifically conventional to segregate the universe into space, time and matter (mass-energy) but even a simple distinction like this is contentious, demonstrating the shifting and uncertain foundations of science. How can we unambiguously define each of these entities without reference to the others? We know from relativity theory space, time and matter interact in a way that makes their physical and theoretical isolation questionable. It has, for example, been postulated that matter is highly condensed space-time. In particular we learn from General Relativity that space and time are inextricably co-variantly woven together into the fabric of the universe, any measurement of one affecting that of the other. Nevertheless, since time is treated as a separate dimension of space-time and because there are many occasions (especially in daily life) when the space-like component of space-time is irrelevant to discussion, it becomes meaningful to speak of time alone, although the underlying co-variant relationship with space should always be kept in mind. Within the physical universe of space-time we cannot say with certainty whether space-time is substantival (absolute) (existing independently from other things as a substrate) or simply relational. This is a long-standing debate that is still not fully resolved. However, it is the view presented here that time is an objective part of the fabric of the universe and should be treated philosophically as an object, not as a relation. In other words time (T*), contrary to much philosophical thinking – most notably that of McTaggart – is real. The most persuasive demonstrations of its reality came after McTaggart’s paper of 1908 (which claimed the unreality of time) through Einstein’s predictions of time dilation e.g. time clocks on aircraft circling the Earth give different readings relative to clocks on Earth, and it is possible to calculate the precise difference according to relativity theory. Such experiments are remarkable because they are counterintuitive and demonstrate the physical reality of time and its physical effects in situations that are independent of human percepts. If we accept the physical reality of time, how does this bear on the complex semantic web of temporal ideas that are presented to us in everyday discourse? The future plays a vital role in all of our lives and yet few would claim that it is real. In claiming that it is unreal we are not denying that it is of vital, possibly critical, importance to our mental functioning, but that it has no reality beyond our minds in the external world. What are the subjective and objective components of time? In everyday discourse (and some scientific discourse) the word ‘time’ is used with several connotations that have philosophical consequences. The future is what has not yet happened, the past is what has happened, and the present is what is happening now. Nothing happens in the future or the past but we can subjectively anticipate, imagine or project into the future, and have memories and imaginative scenarios of the past. But all anticipation and memory is subjective and, most importantly, it occurs in the present. Since there is no objective past or future now, nothing can flow from future through present to past except in our minds: events just happen, they cannot literally move towards us from the future, except as calculated subjective projections. However, time does lapse in the present and this gives us the sensation of movement that we call the passage of time. Time lapse is real and objective but it is not spatial, and time is not a substance, therefore its description using spatial and substance words such as length, flow, distance and passage is metaphor. Temporal “passage” as literal spatial and substantial movement is illusory, but as lapse of time which feels like spatial movement it is objective and real, it is just that the spatial language so often used is inappropriate. Time lapses in the present and is temporal not spatial. All spatial talk of accretion and extension is similarly inappropriate, as is talk of things coming into, and going out of, existence. All this implies movement of events or things into and out of the past and future. There are simply changes in the present. In summary, the present is real and consists of our subjective response, the specious present, to the objective now, which is time itself. The past and future are not objective constituents of the universe but subjective memory and anticipation. Therefore monadic temporal properties like pastness, presentness and futurity, and being one week past, 1 day future etc (A-properties) have no objective counterparts. Objective, physical time is the now: what has been described as the knife-edge between what we call past and future, between indeterminacy and determinacy; the actuality between potentiality and unalterable necessity: it is different from the psychological now. The place of now in the universe will depend on its relativistic frame of reference but it is, nevertheless, an objective part of the physical world. There was a now at the Big Bang and a now as the universe and biological organisms evolved, and that cosmic now did not depend for its existence on the presence of human observers. The history of the universe, of the rock strata and the fossils they contain, and of the organisms that have evolved, bear witness to an objective now of the past. We sense time always, but measure it using clocks of various kinds – instruments with isochronous intervals. The human psychological now (specious present) is not of a precise length but of a period suitable for our biological adaptation to the threats and needs of our environment. It is sufficiently short to make us concentrate when driving cars or playing table-tennis – occasions when our judgement of now can be critical. The psychological now is an adaptation to the objective now of the universe. When people in different countries tune in to a football match on television, the simultaneous now is not a common illusion or a mutual convention, it is a public and objective reality. The now of the universe is divisible to the finest precision of our most accurate clocks and finer still. Time is not simply the temporal relations between events. The relations of earlier than, simultaneous with and later than do not account for duration, which we can both sense and measure. Time is not space: it is not the movement of the hands, or the flashing of numbers on a clock (it is the temporal intervals they represent); it is not change (although we can hardly imagine time without change); it is not spatial length as represented by a line (although we can represent time with a line, time is not the line itself). Temporal length as represented by the aging of everything that is actual. Time moves in the sense that temporal distances can increase and decrease, but these are not spatial distances, and therefore the movement of time is not the same as the movement of a river. It therefore does not make sense to ask how fast time flows. Since all the major aspects of time we have considered – becoming, duration are objective, they are therefore part of the empirical world and therefore essentially a matter for science (physics) rather than metaphysics, although philosophy can assist in clarifying concepts. The solution to the problems of time cannot be semantic – it must be empirical. [The description of time is largely an empirical matter. What time actually is, and the role it plays in language] Time is an unspace-like dimension.Media Gallery

The Physics and Philosophy of Time

The Royal Institution – 2018 – 54:53Time: Do the past, present, and future exist all at once?

Big Think – 2020 – 12:53— First published on the internet – 1 March 2019