William Dampier

William Dampier – 1651-1715

Painted in c. 1697-1698, holding his first published travelogue</strong>

National Portrait Gallery – Artist Thomas Murray (1663-1734)

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Dr Gulliver – Accessed 13 January 2020

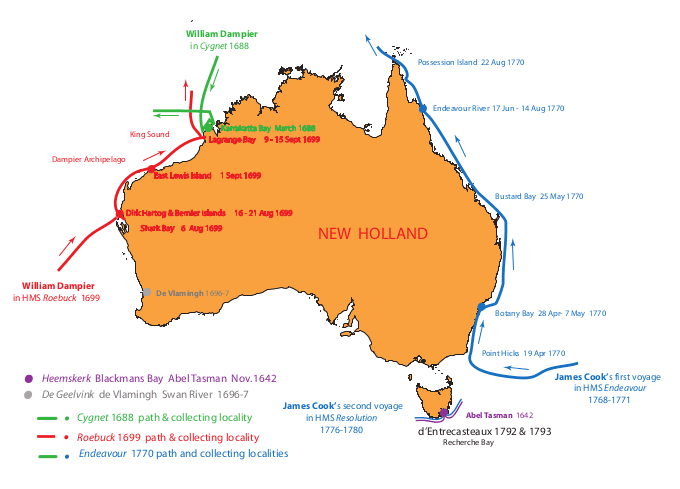

Coastal exploration of Australia

William Dampier in Cygnet (1688) & Roebuck (1699)

James Cook in Endeavour (1768) and Resolution (1776)

Brief visit to Van Diemen’s Land by Frenchmen D’Entrecasteaux with botanist Labillardiere & gardener-botanist Delahaye (1792 & 1793)

At this time Australia, mainly its most-sighted western region, was known as New Holland while Tasmania still retained its Dutch name of Van Diemen’s Land.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The London based British East India Company (EIC) played a lesser role than the VOC in these early days. The first recorded sighting of the Australian mainland by an Englishman was by John Brookes in the EIC ship HMS Tryall on 1 May 1622 when he spotted land near Point Coates south of North West Cape, WA before running aground on a reef and sailing in his skip to Batavia.[1]

If there is error concerning Vlamingh’s 1697 plant collections then the first samples taken to Europe, and certainly the first conclusively recorded specimens that are still extant, were made by Englishman William Dampier.[2]

William Dampier (1651-1715)

Born in East Coker, Somerset in 1651, William Dampier was well-educated but by the time he was sixteen he was orphaned and keen to see the world, joining a merchant vessel sailing to France, then Newfoundland and at age 18 to the East Indies, followed by experience in naval battles against the Dutch in 1673. Then, after falling briefly ill he had travelled to Jamaica where he became owner of a sugar plantation. As this did not suit him he was soon looking for more adventure, this time logging in the Gulf of Mexico when, after a storm wrecked his lodgings, he decided to take up the life of a pirate.

In the late 17th century piracy was rife in certain regions of the globe, especially the East Indies, Caribbean and Pacific where it was a major menace to shipping. As the Spanish empire was thriving on gold, gems, and spices it was Spanish ‘treasure’ that attracted attention. Privateers were ‘respectable’ pirates operating under a license and sometimes financed by businessmen or government who would expect a share of any seized booty. In 1683 Dampier had joined a group of privateers carrying out raids on the Spanish in Panama and Peru, capturing Spanish ships and working the Caribbean, then crossing the Atlantic and sailing up the Pacific coast of South America.

Voyage of the Cygnet

In 1686 Dampier joined the crew of a small privateer trading vessel called the Cygnet with Captain Charles Swan, hunting spoils in the affluent Dutch East Indies. The intention was to sail from the Mexican coast to Guam, a distance of about 8,000 km across the pacific, a feat achieved in 50 days by Francis Drake in 1579, one hundred years before. It was, however about two months before they reached Guam where they loaded up with rice, watermelons, pineapples, oranges, and limes. Dampier also makes mention of the popular local breadfruit which would later feature in the voyages of Cook and Bligh. After leaving the captain on shore at Mindanao in the Philippines the ship then patrolled the China Sea for a year before putting in at Timor before heading south to make landfall on the north-west coast of New Holland on 14 January 1688.

They were off the Kimberley region probably near the Lacepede Islands, the ship then rounding Swan point into King Sound and the mouth of the Fitzroy River where the sailors landed on one or more of the islands before careening Cygnet and doing repairs in a ‘sandy cove’, almost certainly present-day Karrakatta Bay to the southwest of Swan Point which was left on 12 February. The pirates were the first British to set foot on the land some 80 years before Cook and his men and a century before settlement.

Dampier had taken great care of his notes during the voyage, storing them in waterproof bamboo cylinders sealed with wax. Arriving back in England in 1691 he published the journals of this voyage as A New Voyage Round the World. Within two years of its first publication in London in 1697 it had run to four editions, being translated into Dutch (1698), French (1698) and German (1702).[3] Another travelogue of his exploits, Voyages and Discoveries, appeared in 1699 but this time combined with a hydrographic treatise A Discourse on tradewinds … . Together these publications would establish his scientific credentials and celebrity status, and confirm him as an authority on the Pacific region.

During his visit to New Holland Dampier had time to reflect on the voyage and make extensive notes about the arid coast to the south of the Kimberleys, the aboriginals he had met, and the natural history of the area. No plants were gathered on this first visit but his 1697 account gives us among the earliest descriptions of Australian vegetation:

‘New Holland is a very large Tract of Land. It is not yet determined whether it is an Island or a main Continent; but I am certain that it joyns neither to Asia, Africa, nor America. This part of it that we saw is all low even Land, with Sandy Banks against the Sea, only the Points are rocky, and so are some of the Islands in this Bay’.

‘The Land is of a dry sandy Soil, destitute of Water, except you make Wells; yet producing divers sorts of Trees; but the Woods are not thick, nor the Trees very big. Most of the Trees that we saw are Dragon-trees, as we supposed; and these too are the largest Trees of any there. They are about the bigness of our large Apple-trees, and about the same heighth: and the Rind is blackish, and somewhat rough. The Leaves are of a dark colour; the Gum distils out of the Knots or Cracks that are in the Bodies of the Trees. We compared it with some Gum Dragon, or Dragon’s Blood, that was aboard, and it was of the same colour and taste. The other sorts of Trees were not known by any of us. There was pretty long Grass growing under the Trees; but it was very thin. We saw no Trees that bore Fruit or Berries.

For a full account of Dampier’s first visit see http://gutenberg.net.au/ausdisc/ausdisc1-09.html

The Dragon trees referred to are likely the Dragon’s Blood Tree of the Canary Islands (Dracaena draco) which oozes a blood-like resin that has been used to varnish string instruments. Bloodwood eucalypts (formerly in the genus Eucalyptus but now in the genus Corymbia) also secrete a red gum, those growing on this part of the coast – the trees presumably referred to by Dampier here – now being appropriately named Corymbia dampieri.

Voyage of the Roebuck 1699-1701

Dampier was keen to return to the South Seas and so, having established his scientific credentials with the Royal Society, his request to the British Admiralty for a ship was immediately approved. His brief was to investigate the uncharted eastern coast of New Holland sailing via the Pacific Ocean round Cape Horn and, in the process, perhaps solve the mystery of the fabled Terra Australis Incognito.

As an expedition dedicated to both exploration and scientific study this was a first for the British Admiralty. He was to survey ‘all islands, shores, capes, bays, creeks and harbours, fit for shelter as well as defence’ also bringing back specimens of animals and plants with an artist to ‘sketch birds, beasts, fishes and plants’ and even to bring back a a sample native ‘providing they shall be willing to come along’.[13]

As captain of HMS Roebuck, he departed England on 14 January 1699, but because of delays in preparation he sailed, not via the Horn, but via Bahia in Brazil, bypassing the Cape of Good Hope which was controlled by the Dutch, and sailing directly to New Holland. He had with him a chart of the western coast of New Holland made by Abel Tasman more than 50 years before.[4]

Within six months of his departure from England he was back on the west coast of New Holland and by 6 August 1699 was making notes on the organisms he had found in an inlet where the ship landed to pick up water, naming it Shark Bay because of the numerous sharks hooked by his men.[5] Sailing north he landed on Dirk Hartog Island, staying from 16th to 21 August then again proceeding north, collecting specimens (stored between the pages of books)[6]at East Lewis Island in the Dampier Archipelago off present-day Dampier, on 1 September. In today’s Dampier Archipelago he visited an island that he called Rosemary Island on account of a blue flowered plant that looked like the Mediterranean Rosmarinus officinalis which today we assume was Olearia axillaris. There was then a final third period of collecting at Lagrange Bay about 150 km south of Broome from 9-15 Sept, mostly on Dirk Hartog Island.

Having little idea of how to preserve his specimens Dampier had the plants, birds and fish sketched by a crew member (a procedure encouraged by the Royal Society as early as 1665) and these sketches were later combined with his descriptions in his published journal which was the first recorded graphic representation of plants and animals of New Holland.[7]

With the ship in poor condition charting the east coast was abandoned (it would be 80 years before Cook would complete this task and exactly 100 years before settlement) and he headed for Timor and home, but the decrepit Roebuck foundered at Ascension Island between Brazil and the west coast of Africa on 21 February 1701, running ashore to leave about 60 sailors marooned for five weeks before being picked up and returned to England in August 1701, along with Dampier’s plant specimens.

On arriving back in England his account of this second 1699–1701 expedition to New Holland appeared as A Voyage to New Holland (1703 and 1709) but he was court-marshalled from the navy for, among other things, loss of the Roebuck, and cruelty to his Lieutenant and a boatswain, and as a penalty his pay for the voyage was docked. To recoup his costs Dampier returned to writing and, in 1703, published another travelogue, A New Voyage to New Holland &c in the Year 1699 which appeared in two volumes released in 1703 and 1709.

Third global circumnavigation

But with an obvious wanderlust he could not stay on land, returning to the sea for a third circumnavigation in 1708 in two ships the Duke and Duchess following a life of privateering until 1711 when he returned to England living long enough to enjoy his wealth and dying in London in 1715 at age 64.

As a swashbuckling adventurer and observant writer who recorded tides, winds and currents Dampier earned the admiration of many distinguished explorers including von Humboldt, Banks, and Darwin. Remarkably, being an early recorder of novelty, over 1000 words in the Oxford English Dictionary are first used in his books e.g. ‘avocado’, ‘barbeque’ and ‘chopsticks’ .[14]

Dampier’s specimens; their names and description

Botanical specimens from the Roebuck expedition, which he had preserved between the pages of a book, were presented to the Royal Society via naturalist John Woodward (1665-1728), a Fellow of the Royal Society, and Professor of Physic at Gresham College London [15] They are now held by the Fielding-Druce Herbarium of the Department of Plant Sciences at Oxford University.[8]

Altogether 66 specimens in the herbarium are attributed to Dampier (27 from the Americas, 27 from Australia, 9 from SE Asia and three unknown).[17] 18 specimens were collected from Shark Bay, one of them being the Sturt’s Desert Pea, Swainsona formosa, the floral emblem of South Australia.[9] Unfortunately these specimens had become mixed with others he had collected earlier in Brazil. Woodward then passed on the specimens to England’s foremost botanists John Ray (1628-1705) and Leonard Plukenet (1642-1706).

Nine of the specimens were described by Ray the ‘father of British botany’ in his Historiae Plantarum Generalis (1704),[10] those described by Leonard Plukenet (probably 9) appeared in Amaltheum Botanicum (1705), eight of them illustrated as copper engravings by botanical artist J. Collins. It is also likely that the first moss ever described from Australia was part of the collection, described by Johann Dillenius (1687-1747) in his Historia Muscorum (1741).[16] The significance of the collections was not realized until viewed by Robert Brown (1773-1858) when visiting the herbarium at Oxford while preparing his Prodromus Florae Hollandiae et Insulae Van-Diemen[16]

Plant descriptions at this time pre-dated Linnaean binomial nomenclature (see page) and consisted of ‘phrase names’ (brief Latin descriptions also referred to as polynomials). The accepted starting date of modern botanical nomenclature is the first edition of Linnaeus’s Species Plantarum of 1 May 1753. Linnaeus visited London and Oxford between 1735 and 1738 where Dampier’s specimens were housed but, surprisingly, did not take up any of these names in his famous botanical compendium.[11] Twenty four sheets remain in the Dampier Herbarium (17 from New Holland ) along with a solitary brown seaweed, Cystoseira trinodis, figured in his 1703 publication and the first published record of an Australian seaweed.[12]

Plant commentary & sustainability analysis

Dampier was the first person to circumnavigate the world three times, visiting the Australia-to-be twice in the process. Other relevant ‘firsts’ include: the first fully authenticated plant collections in New Holland; the first wide-ranging account of the country’s natural history and people (although his overall impressions were in agreement with the sentiments of the Dutch mariners who had preceded him); first description of breadfruit (leading to voyage of the Bounty).

His escapades were the source of inspiration for Danial Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Coleridge’s poem Rime of the Ancient Mariner. His accounts were to be standard reading for all the subsequent voyages of scientific exploration.

William Dampier is commemorated in the genus Dampiera described by Robert Brown in 1810.

Timeline

1577 to 1580 – Englishman Francis Drake (1540-1596) completes second circumnavigation of the world following that of the Spanish Ferdinand Magellan expedition from 1519 to 1522

1622 – The first recorded sighting of the Australian mainland by an Englishman was by John Brookes in the skip HMS Tryall on 1 May 1622 when he spotted land near Point Coates south of North West Cape, WA before running aground on a reef then sailing to Batavia

1686 – Privateer William Dampier joins the crew of a small privateer trading vessel Cygnet with Captain Charles Swan, hunting spoils in the affluent Dutch East Indies

1688 – 14 January. Cygnet makes landfall on the north-west coast of New Holland on 14 January 1688 after visiting Timor

. . . February – careening Cygnet and doing repairs in a ‘sandy cove’, almost certainly present-day Karrakatta Bay to the southwest of Swan Point which was left on 12 February. The pirates were the first British to set foot on the land some 80 years before Cook and his men and a century before settlement

1691 – Dampier returns to England and publishes A New Voyage Round the World which sells on the continent and runs to four editions

1699 – Dampier publishes a further travelogue Voyages and Discoveries but this time combined with a hydrographic treatise A Discourse on tradewinds . . .. Together, these publications would establish his scientific credentials

. . . 14 January, Dampier sets sail as captain of HMS Roebuck via Bahia in Brazil, bypassing the Cape of Good Hope which was controlled by the Dutch, and sailing directly to New Holland. He had with him a chart of the western coast of New Holland made by Abel Tasman more than 50 years before

. . . 16-21 August lands at Dirk Hartog Island then proceeding north

. . . 1 September collects specimens (stored between the pages of books) at East Lewis Island in the Dampier Archipelago off present-day Dampier

. . . 9-15 September – a third and final period of collecting at Lagrange Bay about 150 km south of Broome. Dampier had the plants, birds and fish sketched by a crew member (a procedure encouraged by the Royal Society as early as 1665) and these sketches were later combined with his descriptions in his published journal which was the first recorded European graphic representation of plants and animals of New Holland

1703 & 1709 – Dampier publishes an account of his second 1699–1701 expedition to New Holland as A Voyage to New Holland but was court-marshalled from the navy. A specimen of a brown seaweed, Cystoseira trinodis is the first published record of an Australian seaweed

. . . to recoup costs he returns to writing with a further travelogue A New Voyage to New Holland &c in the Year 1699 before returning to privateering

1741 – A moss from one of Dampier’s 1699 collections described by Johann Dillenius in his Historia Muscorum is the first moss ever described from Australia