World Flora

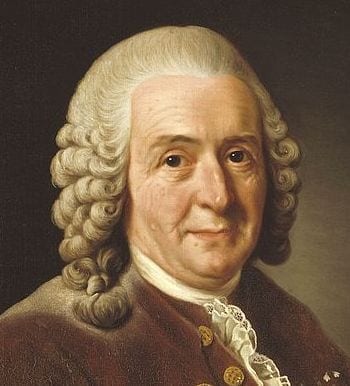

Carl Linnaeus (1718-1793) aged 68

Painted by Alexander Roslin in 1775

Scientific communication needs universally accepted principles, procedures, and terminologies

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Accessed 28 July 2023

Introduction – World Flora

Establishing a simple inventory of all the different kinds of plants that exist on planet Earth (a world flora) might seem, at least in principle, an uncomplicated enterprise.

But, what were the necessary preconditions for the development of a scientific (universal) communication about all the plants growing on the Earth and in its oceans?

A standardised scientific language

To compile a formal list of communicable plant names and descriptions we must have a community of like-minded people, an accepted methodology for generating names and groupings (classifications) as well as an agreed terminology for the plant parts that distinguish one kind of plant from another. In other words, to communicate about plants in a systematically shared way there must be a standardization of procedures. Such a formal system could surely have been developed in a simple form before there was the written word, but the advent of writing would have greatly facilitated this process.

The Scientific Revolution in the West

The systematization of knowledge about the natural world is something we associate primarily with the Scientific Revolution that occurred in the Western world, developing partly out of the naturalistic, analytic, and objective cast of thought developed by Presocratic philosophers that was passed on to the classical world, and partly from the encyclopedic desire to describe the many new organisms that were being encountered by the West during the Age of Discovery and Enlightenment as a period of European colonial expansion. Though there are always exceptions, for the most part, it seems that the great historical cultures of India, China, and the East continued to think about plants primarily for their utility – especially for medicine – while a distinctive ‘scientific’ Western approach, usually attributed to the plant studies of Theophrastus at the Lyceum in ancient Athens, studied plants for their own sake and for a detailed comparison between one plant and another rather than that between plants and humans. The effectiveness of Western science, its principles and procedures, became self-evident to all nations and has now become a globally accepted way of communicating about plants within the academic community.

Floras – plants from particular geographic regions

The man who managed to devise a European-wide standardized system for the presentation of plant scientific knowledge was Swedish Naturalist Carl Linnaeus (like many other scientists he used a Latinised form of his name in deference to the language of classical learning).

With a standardized method of plant description, it then became much easier to communicate more meaningfully about plants, to write accounts of plants growing within particular regions, and to assemble plant collections of various kinds on grand estates, in botanic gardens, and as dried plants stored in plant museums called herbaria.

A scientific account of the plants growing within a particular region became known as a Flora (with a capital ‘F’) and it arranged the plants within a scientific classification that included botanical descriptions of the plants with their authors (a citation indicating where the plant was first described) as well as notes on where the plants can be found, how one can be distinguished from another (identified) and other useful botanical information including illustrations showing the distinguishing characteristics.

The process of scientific plant inventory has been a cumulative one until today plant scientists are well on the way to building up a complete inventory of all the plants in the world … a world Flora. This only became possible as a result of the improved transport and communication systems that have been an integral part of globalization.

This article sketches the historical process that made the systematic description, classification, and illustration of the world’s vegetation possible.

Plant classification

The listing of any large number of objects is simplified by arranging them into groups or categories of various kinds (see plant classification). Early (non-utilitarian i.e. scientific) plant classification systems found in documents of both the West and East divided plants up based on simple and obvious features – whether they were a tree, shrub, subshrub, or herb, the system used for example by Theophrastus around 350 BCE.

This mode of classification continued until a major overhaul in the West during the 18th century Age of Enlightenment when Carl Linnaeus developed a method of subdivision based on the plant’s sexual organs, a method of ‘artificial classification’ called the ‘sexual system’. Other botanists based their groupings on obvious physical similarities using ‘natural classifications’ but Linnaeus’s system was a popular and usable starting point.

The acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution revolutionized thinking about plant classification as plant species, assumed to be unchanging creations of God, became the slowly changing, over many generations, descendants of a common ancestor. This subsequent arrangement of organisms into evolutionary units was known as ‘phylogenetic systematics’ and with the ability to analyse modern genetic data using powerful computers we have entered the age of cladistics (the elucidation of hypothetical evolutionary branching patterns) and molecular systematics.

How many different plants are there in the world?

Today we have good maps of the distribution and general composition of vegetation across the planet. We are also aware of several general features: that land occupied by natural vegetation is being constantly appropriated by cultivated plants; that in very general terms as you move towards the equator the number of species per unit area increases (in Europe the number of native vascular plant species is estimated at about 13,000 with Britain about 1600, France 4400, Spain 4900; the Amazon basin has about 20,000. In America the more northern British Colombia has about 2500 species while the more southern California has about 5000 while on the equator Ecuador and Colombia greatly exceed these numbers; Australia has about 23,000) climate is clearly a major determining factor here along with recent glaciations around the poles.

An indication of the evolving human perception of world plant diversity comes to us from the historic speculation on global plant species numbers made by Western science on the way to today’s much less speculative figure of about 342,000 species now claimed to be accurate to within about 10%. David Mabberley’s Plant Book (2017) lists 13,300 genera of vascular plants.

Plants in cultivation

We have just passed through a major period of cultivated plant globalization – a time when the world’s botanical bounty has been spread among the world’s peoples – the redistribution of temperate cereals and tropical crops, medicinal plants and spices, species of plantation forestry, and ornamental plants. This all occurred mainly within the Age of Plants (c.1550-1950).

Though the collection of plants is not unusual it became a special feature of the European Age of Plants as botanists began the process of global inventory and encyclopedic description that was part of the Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment. Though vast areas of land were quickly covered by crop monocultures, plant diversity was explored in the living collections of leading European botanic gardens keen to hold the most species.

The increasing numbers of their holdings give us an insight into the degree of exploitation of the world flora.

1660 – Jardin du Roi, Paris (later Jardin des Plantes – c. 4000 species (Stafleu 1969)

1720 – Hortus Botanicas Leiden – 5846 species (Boerhaave 1720)

c. 1760 – Chelsea Physic garden – c. 5000 (Uglow 2005, p. 147)

1789 – Kew Gardens 3-vol Aiton’s Hortus Kewensis – c. 5500 species.

1813 – Hortus Kewensis – >11,000 species.

Botanical stepping-stones on the way to a world Flora

The classical world bequeathed to the West several substantial plant compendia: the Hippocratic Corpus attributed to the medico Hippocrates of Cos (c. 460-c. 370 BCE); the approximately 500 plants listed in Theophrastus’s (c. 371-c. 287 BCE) works; the encyclopaedic Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE); and the materia medica of Pedanius Dioscorides (c.40-90 CE). These were works that each borrowed freely from their predecessors in a tradition that continued Deference to the past meant that the lists of approximately 600 plants that had appeared in the materia medica of Dioscorides would be repeated again and again in the derivative printed herbals of the Middle Ages. Only towards the end of the era of herbals (c. 1470-1670) were new plant discoveries added to plant compilations as interest in medicinal properties took on more of the character of regional floras. This was at a time when botany was diverging from medicine with the appointment of botany professors to curate the physic gardens of the medical faculties universities in Renaissance Italy.

The legacy of the Classical and Medieval worlds to the European Scientific Revolution was a total of around 1000 descriptions of different species of plants (Morton 1981, p. 145).

Botanists focus on the development in methods of plant classification that occurred from the Early Modern period onwards but it must be remembered that these classifications were also a way of organising the increasing number of plants becoming known to Western science through the Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment, and it is interesting to follow the historical numerical increase in plants known to science as represented by these botanical compendia. The nationalities of leading botanical scientists at any given time tended to reflect the cultural, economic and political status of the European countries where they worked: Italy in the 16th century, mostly France but also England in the 17th century, France and Germany in the 18th century, while France, Germany and Britain all produced great botanists in the 19th century but work on plants of the British empire would draw together the plants present over a large part of the Earth’s surface.

A. Caesalpino (1519-1603) – De Plantis (1583) – 1500 species.

G. Bauhin (1560-1624) – Pinax Theatri Botanici (1623) – 6000 species.

J. P. de Tournefort (1656-1708) – Institutiones Rei Herbariae (1700) – 9000 species.

J. Ray (1627-1705) – Methodus Plantarum Novus (1682, 2nd edn 1703) – 18,000 species.

C. Linnaeus (1707-1778) – Species Plantarum (1753) + Genera Plantarum (1737) – 7700 species.

C.L. Willdenow (1765-1812) – Species Plantarum 4th edn (1797) – 6 vols and >16,000 species.

A.P. de Candolle (1778-1841) Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis (1824–1873) 17-volume treatise intended it as a summary of all known seed plants, 7 volumes completed before his death a further 10 edited by his son A. de Candolle (1806-1893) but remained incomplete, dealing with about 58,000 species of dicotyledons only.

Complementing this accounts were compendia of genera:

S.L. Endlicher (1805-1849) – Genera Plantarum – 6835 genera of plants

G. Bentham (1800-1884) & J.D. hooker (1817-1911) – Genera Plantarum (1862-1883) – 7569 genera of seed plants.

J.C. Willis A Dictionary of the Flowering Plants and Ferns (rev. H.K.A. Shaw) (1973)

R.K. Brummitt (1992). Vascular Plant Families and Genera includes 13,888 accepted genera.

D. Mabberley (1948->)The Plant-book (2008). The revised edition of (2017) lists 13,300 genera of vascular plants

Also from the time when modern botanic gardens first appeared in Italy in the mid-16th century there was a gathering competition to collect and cultivate the greatest number of species. The figures here are string indicators of a country’s political and economic fortune as well as its capacity to interest botanical scientists.

Part of the 19th century British colonial enterprise was what amounted to a botanical inventory of the British Empire. This was a consolidation of biological inventory that had gathered momentum during the Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment, it included Floras of: North America, Flora Boreali-Americana (W. Hooker, 1829-1840); Antarctica (J.D. Hooker, 1844-1847); New Zealand, Flora Novae-Zelandiae (J.D. Hooker, 1852-55); Tasmania, Flora Tasmaniae (J. Hooker, 1855-1859); West Indies, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Enumeratio plantarum Zeylaniae (G. Thwaites & J. Hooker, 1858-1864); Flora of the British West Indian Islands (A.H.R. Grisebach, 1859-1864 (3 vols)); Cape of South Africa, Flora Capensis (W. Harvey, O. Sonder & W. Thistleton-Dyer, 1859-1933 (7 vols)); Hong Kong, Flora Hongkongensis (G. Bentham, 1861); Australia, Flora Australiensis (G. Bentham & F. Mueller, 1863-1878 (7 vols); British India, Flora of British India (J. Hooker, 1872-1897 (7 vols)).

At the turn of the 20th century plant taxonomy was dominated by the great German systematist H.G.A. Engler (1844-1930) which evolved into three major works: Die Naturlichen Pflanzenfamilien (1887-1915 with K.ZA. Prantl) a massive revision of the higher ranks of the plant world to genus and sometimes sub-generic ranks; Syllabus der Pflanzenfamilien (1892 to 12th edition edited by Melchior in two volumes, 1954 and 1964) a revision to family level; and Das Pflanzenreich (1900-1953) of many authors as an attempt at a modern-day Species Plantarum, never completed but extending to 107 volumes. These latter works are the closest we get to a world monograph in the period preceding the computer.

World Flora online

Global plant inventory has now entered the information age with the work of the World Flora Online http://www.worldfloraonline.org/ (WFO) an international initiative of the Global Partnership for Plant Conservation to facilitate the protection of endangered species and the investigation of plants with potential health, social, environmental and economic benefits. In 2010 an updated Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (a component of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity) established Target 1 as ‘an online flora of all known plants’. In 2012 representatives from four institutions: the Missouri Botanical Garden, the New York Botanical Garden, the Royal Botanic garden Edinburgh, and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – all members of the Global Partnership for Plant Conservation undertook to achieve this target by 2020, proposing an outline of the scope and content of a World Flora Online and a consortium of institutions and organizations to collaborate on providing that content and by August 2014, 24 institutions and organizations had signed a memorandum of understanding as participants of a collaborative, international WFO Consortium contributing to a consolidated global information service on the world flora.

Historical commentary

The publication of a comprehensive World Flora, providing an exhaustive inventory and description of all plant species on Earth, is a monumental undertaking with a rich historical background dating back centuries. The concept of compiling a global botanical inventory has intrigued and challenged scientists, botanists, and naturalists for generations, reflecting humanity’s enduring fascination with the diverse and complex world of plants.

The origins of botanical exploration can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where plant knowledge was primarily utilitarian, focusing on medicinal, culinary, and decorative applications. Early civilizations such as the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans documented plants for their practical uses, with texts like the Ebers Papyrus and the works of Theophrastus providing valuable insights into ancient plant taxonomy and classification.

During the Age of Exploration in the 15th and 16th centuries, European voyages to distant lands brought back a wealth of new plant species, leading to the establishment of botanical gardens and the emergence of botanical study as a scientific discipline. Notable figures such as Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, revolutionized the classification of plants with his system of binomial nomenclature, laying the foundation for organizing and categorizing plant diversity.

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed an explosion of botanical exploration and discovery, fueled by expeditions to remote corners of the globe in search of new plant species. Pioneering botanists like Sir Joseph Banks, Alexander von Humboldt, and Charles Darwin embarked on groundbreaking journeys, documenting flora from diverse ecosystems and contributing to the burgeoning field of plant science.

The publication of regional floras became increasingly common during this period, with botanical expeditions producing detailed accounts of the plant species encountered in specific geographical areas. Works such as Flora Graeca, Flora Lapponica, and Flora Brasiliensis provided valuable insights into the plant diversity of Greece, Lapland, and Brazil, respectively, showcasing the beauty and complexity of regional flora.

As scientific exploration expanded and botanical knowledge accumulated, the idea of compiling a comprehensive World Flora gained traction among the global botanical community. The monumental task of cataloging every plant species on Earth seemed daunting but essential for understanding the planet’s biodiversity and preserving its natural heritage.

In the 20th century, advancements in technology, including the development of herbaria, botanical databases, and molecular research techniques, revolutionized plant taxonomy and systematics. The rise of international collaboration and initiatives such as the Flora Europaea and Flora of China demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale botanical projects spanning multiple regions and countries.

The publication of the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants (ICN) in 2011 standardized plant taxonomy and nomenclature worldwide, providing a framework for botanical research and communication across borders. Global initiatives such as the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation and the Millenium Seed Bank Partnership underscored the importance of plant diversity conservation and sustainable resource management on a global scale.

In recent years, the advent of digital technology and online platforms has facilitated the sharing of botanical data and resources, enabling scientists and researchers to collaborate more effectively and access information on plant species from around the world. Projects like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and the Plant List have provided valuable tools for compiling and disseminating plant information on a global scale.

The proposal for a unified World Flora, encompassing all plant species on Earth in a single comprehensive publication, represents a bold and ambitious endeavor that holds immense scientific and educational value. Such a monumental undertaking would require extensive collaboration among botanists, taxonomists, ecologists, and conservationists from every corner of the globe, pooling their expertise and knowledge to create a definitive resource on the world’s plant life.

A World Flora would not only serve as a valuable reference for scientists and researchers but also as a source of inspiration and wonder for plant enthusiasts and nature lovers worldwide. By documenting and celebrating the incredible diversity of plant species that inhabit our planet, a World Flora would underscore the importance of plants in sustaining life on Earth and highlight the urgent need for their conservation and protection.

In conclusion, the historical background to the publication of a World Flora is a testament to humanity’s enduring curiosity and reverence for the natural world. From ancient civilizations to modern botanical expeditions, the story of botanical exploration and discovery has been marked by passion, perseverance, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. A World Flora would be the culmination of centuries of botanical research and exploration, encapsulating the beauty and complexity of the plant kingdom in a single, comprehensive volume for generations to come (AI Sider July 2024)..

Citations & notes

See also Kew’s Plants of the World Online.

References

Smith, G.F. 2017. The World Flora Online. Annals of the Missouri Botanic Garden 102: 551-557