Worldviews

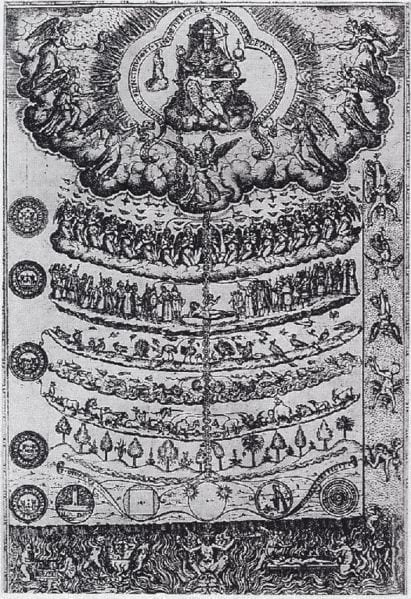

Great Chain of Being – The Natural Order

Illustration of the Ladder of Life from Rhetorica Christiana by Didacus Valades – 1579

A pictorial (and mental) representation of the world order

Everything is arranged like the steps of a ladder

From God – to rulers – to common people – to animals – to plants – to rocks

higher to lower

perfect to imperfect

spiritual to material

rational to irrational

complex to simple

God in blissful heaven above, the Devil in burning hell below

Everything is in its God-ordained fixed place in an eternal natural order of matter and moral worth

The connecting ‘chain of being’ runs up the centre.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons – Duncharris – Accessed 29 Apr. 2016

Introduction

Simply by being, by existing, we are confronted by some very obvious and simple general questions to which there are no obvious and simple answers. Let’s have a look at some of these ‘existential’ questions.

Who am I? Why am I here? How did I get here? What other things are here with me . . . what are they made of, how did they get here, and what are they all doing? Of all these other things apart from me, which ones are important to me and why? Why does some particular thing happen rather than something else, that is, why do things happen in an orderly way? How should I behave towards the people around me and how do I justify behaving in one way rather than another? How do I know anything at all? Will I end, or will I live in some way forever? Will everything else end . . . and how did everything begin? We get particularly preoccupied with explanations for origins . . . of the universe, of life, of humans, of consciousness, of our national, religious, or ethnic group, of language, of flowering plants . . . and so on.

We might to pass over these questions in daily life as though they don’t matter to us. We dismiss them by perhaps assuming we know the answers . . . or that we can never know the answers . . . or we think that science and/or religion can provide adequate answers . . . or maybe we live each day as it comes without worrying about such things . . . maybe the questions just seem embarrassingly silly and we’ve got better things to think about.

Whatever our personal opinion, finding satisfying answers to such questions has occupied humanity from its very beginnings – and it still does – questions about origins, meaning, purpose, science, identity, morality, and destiny. We have an inner curiosity and need for an answer to everything, altogether, and all at once. And surprisingly, from as far back as records go, it is clear that we have always managed to find answers. The answers we have found, the explanations for everything, we call (in English) a ‘worldview‘, ‘grand narrative’, ‘metanarrative’, or . . . maybe (in German) . . . a ‘Weltanschauung’.[2]

All-embracing worldviews exist in every culture providing both individuals and societies with meaning because commonly-held worldviews cement people together with a common identity – and it is this common identity that binds people into systems of flexible cooperation unlike any others in the animal kingdom.

Unfortunately this remarkable source of cooperative social cohesion can also be the source of deep division – when worldviews clash. Worldviews both ‘bInd and blInd’[10] and that is why we need to study them. This is the work of the social scientist.

The Ladder of Life or Great Chain of Being

Trying to represent, in words or pictures, the way the world actually is turns out to be extremely difficult.

How would you do it?

One extremely powerful piece of explanatory imagery presents everything on a graduated scale as a hierarchy that becomes progressively more important and worthy as it passes from ‘bottom’ to ‘top’. So, for example, biologists sometimes describe the world as atoms that are united into molecules, molecules are united into living cells, cells are united into tissues – and so on – to organs, organisms, and populations. These are like ‘levels’ of the world and each level has its own subject of study, principles, rules, and descriptive terms . . . molecular biology, cytology, histology etc.

This biological way of representing the world is very similar to the Ladder of Life or Great Chain of Being that was described by ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle and later absorbed into Christianity although it was probably around much longer than this because it provides a neat and tidy account of something very complicated. Each person knows exactly where they fit into the physical and moral universe, and human society.

The pictorial representation of ‘everything” (given below) provides an excellent example of a worldview – in this instance that of Medieval Europe. Many worldviews are variations on this particular theme.

Religion, natural science, & secular humanism

Grand narratives provide the framework for understanding and explaining the world and our place in it. If we can find one ready-made then it relieves us of the need to provide compelling explanations for everything ourselves. All these difficult and abstract questions can be put to one side so that we can get on with life’s practical necessities.

Historically the desire for communal meaning and collectively-accepted explanations has been satisfied by the great world religions which allow us to overcome explanation by taking an act of faith. Another path would be a grand political ideology, or an overarching interpretation of world history.

Ancient Greek philosophers (see Socrates, Plato & Aristotle), and the pre-Socratic first natural scientists, confronted our lack of understanding of the world, not by blind acceptance and acts of faith, but by trying to ‘think it through’ as best they could, by going back to first principles. Their approach was to organize our thought into simple categories: what exists (ontology), how and what we can know (epistemology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), how we should behave (ethics and politics), the organisation of rational thought (logic), and what is beautiful (aesthetics). This approach did not rule out religious belief but its insistence on reason and evidence reduced the temptation to constantly resort to supernatural explanations.

The first halting steps of natural science were slow, but in the European Renaissance they gave rise to a science whose explanations based on the material world challenged those of religious belief, giving rise to secular humanism which could envisage life without god(s). Grand narratives began to take the form of social ideologies as over-arching explanations of social structure.

Closer to today we can see how large numbers of people have been enthralled by political visions like socialism or Marxism as Utopian grand narratives of social justice and equality, and capitalism as a Utopian vision of unending economic growth, progress and prosperity for all. Wishful grand visions for society like these have been the subject of satirists dystopias like Aldous Huxley‘s Brave New World (1932) or George Orwell’s 1984 (1949).

Our personal worldview

Each one of us has our own grand narrative – our personal explanation of the world, universe, and everything we know – how it arose, how it works, what it all means and, especially, how and where we fit into the scheme of things. It is partly what we have been taught and partly what we have considered for ourselves, and it has much in common with the general beliefs and customs of the society we live in. It is not necessarily a grandiose intellectual theory or something that we could write down but, for most of us, it is, most of the time, something we just assume or accept intuitively. And not having a grand narrative is a grand narrative.

Principle 1 – Whether our personal grand narrative is explicit or implicit it guides our behaviour and without it we could not operate in the world

For both individuals and communities grand narratives are treated as ‘real’ and ‘true’ and we must take them seriously because they are what legitimates the authority that underpins our social institutions – our laws, rituals, beliefs, and customs.

Grand narratives are part of our identity, part of who we are. We therefore hold on to them very dearly and find them extremely difficult to change or place under scrutiny – so difficult to change in fact that we may not allow our views to be challenged. Whether our grand narrative is focused on God, science, democracy, socialism, capitalism, our insistence that we dont have a grand narrative or whatever … we will not abandon it easily.

Comforting myths?

Reality relativity – story-telling & myth – imagined realities

A narrative is a story . . . so are all worldviews simply sources of social cohesion – comforting tales or fictions that help us cope with the mysteries of existence? Are they just functional myths – a deliberate or unconscious strategy for imposing order on society, subjugating peoples’ minds to one particular system of thought or behaviour as way of subduing protest? Karl Marx thought that this applied to Christianity which was the ‘opium of the people”’.

Have you found the one and only complete and authentic account of ‘everything’?

Here is our first big problem. Do we all coexist, peaceably tolerating different or opposing world views? Do we force our own views on others because we know we are right – even if that means taking lives?

How do we assess one worldview against another? Are all grand narratives of equal merit or are some more compelling than others? What can we do when incompatible grand narratives meet? Must it be that one group of people is ‘right’ and the others ‘wrong’, or are all worldviews simply ‘relative’ . . . just ‘myths to live by’? What are our strategies for reconciliation? Can there be any decision procedure for determining which is correct? To what extent are our beliefs soundly based and to what extent are they our own creations – imagined realities – and how can we tell the difference? We can call this the problem of ‘reality relativity’.

If we are all to get along in this world then the very least we can do is make an honest attempt to surmount our difficulties. There is no silver bullet but here are a few suggestions to seriously consider.

1. When encountering an apparent impasse restate the other person’s point of view in a form that they will accept

2. Be prepared to clearly define your own position and why you defend it

3. Make clear what would conceivably settle differences and make reconciliation possible

4. Be aware that in attempting to negotiate common ground agreement is made much more difficult by special pleading – the expectation that we should receive special consideration with respect to our race, religion, social position, or geographic location (sometimes referred to as identity politics)

As a point of departure consider discussing the following proposition:

We use knowledge and reason to maximise human flourishing which is a common-ground foundational morality for humanity

Of course we might think that all these difficulties can be avoided and that we can rise above the crowd by claiming the universe has no meaning (aspects of existentialism and nihilism). Or maybe we mistrust or feel no need for a metanarrative. This is postmodernism, a metanarrative itself – but more of this later.

Secondary worldviews

Would it be possible to develop a grand narrative that was acceptable to everyone – or most people anyway? Is it possible that while the world once consisted of a multitude of different cultures and belief-systems we now have a converging set of beliefs that we can refer to as an emergent global worldview? What would it be like?

The constant barrage of news about human conflict over race, religion, territory, resources, and political affiliation make such a suggestion sound absurdly naive.

Although the really grand narratives account for ‘everything’ (or, at least, they answer really big questions) there are, as it were, secondary grand narratives that circumscribe not ‘everything’, but the content and limits of large domains of our experience and understanding.

Perhaps we can begin an examination of ‘reality relativity’ by seeing how divergent opinions about secondary worldviews have changed over time. Perhaps we can get closer to an understanding of ‘everything’, of reality, by looking at the changing interpretation of some of the the parts out of which it is composed . . .

The secondary worldviews we will look at are:

‘humans & the universe’, ‘factual knowledge’, ‘space’, ‘time’, ‘matter’, ‘value’, ‘spirit’, ‘mind’, and ‘progress’.

Humans in the universe

Anthropomorphism, anthropocentrism, & personification

Humans, once assumed to be at the centre of everything, have come to accept a less exalted position in the scheme of things, largely as a consequence of scientific investigation.

causation in the universe, the reason why things happen, was once attributed to animistic spirits, gods, and other supernatural but human-like agencies is being displaced by a belief in non-supernatural causation acting between ‘things’.

1. Copernicus moved the Earth from the centre of the universe to being one of a number of planets revolving around the Sun. Much later a wider perspective revealed the solar system was at the periphery of the Milky Way, one of billions of galaxies in the universe

2. Darwin provided compelling evidence that, rather than being placed on Earth by God, humans were united with the entire community of life by being a consequence of descent with modification from a common ancestor, with ape-like animals being our closest ancestors. Humans were neither the sole purpose nor pinnacle of the evolutionary tree

Aristotle’s teleology had shown that organisms have intrinsic ends and that these do not depend on their instrumental value to humans. That is, organisms are not placed on the Earth solely for human benefit – the value, good, or flourishing of organisms does not depend on their relationship to humans but lies within the organism itself and its relationship to its environment. As a consequence, their value is not simply a matter of opinion, a product of the human mind, it is an objective fact in the world. The significance of this is that value is not just a product of the human mind. Human values exist alongside other values that exist objectively in the world.

Philosophers, Sigmund Freud, moral and other psychologists, our creative artists, and indeed history itself have demonstrated how quickly the rational human mind can be overtaken by other forces.

Associated with the decline in the privileged status of humans has been a parallel decline in absolutism or foundationalism, the acceptance of certain precepts or conditions as beyond question, absolute, foundational, or otherwise privileged in some special way. Socially this has been most obviously manifest in the challenge to theism, the divine rule of an absolute supernatural being and translated into the Earthly idea of an absolute monarchy. Scientifically we see this most clearly in Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. Perhaps today a similar dogma persists in the assumption of a privileged or foundational state of existence – that of microphysics.

Space

The ease with which anyone with a computer, today, can scan almost every metre of the Earth’s surface using satellite images and Google Earth belies our former ignorance of the earth’s surface. For almost all of human history there have been unexplored distant lands and boundaries that had not been breached. Early Australian settlers less than 200 years ago were convinced that Australia had an inland sea and it took men on horseback exploring the continent to determine that this was untrue. In the last tick of human history all this has changed.

Geographic limits

In ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian and classical Greek cultures the Earth was perceived as a flat disk floating on the sea. In about 850 BCE, at the time of the famous ancient Greek poet Homer, author of the great mythical epics the Iliad and the Odyssey, the prevailing Greek view of the known world (probably the most all-embracing of any people at that time) is described as follows:

The Earth was flat and circular with Greece at the centre and focal point either Mount Olympus or Delphi. The circular disk was divided east-west by the Mediterranean sea. Around the periphery of the disk flowed the tranquil River Ocean in a clockwise direction with the sea and all the rivers obtaining their water from it. To the north lived an inaccessible happy people who did not age or suffer from disease, did not work and did not engage in warfare. In the land were caverns that produce the chill north wind that sometimes blew over Hellas (Greece). To the south were another people that shared banquets and sacrifices with the Olympian Gods. To the west was the Elysian plain where virtuous mortals were transported without passing through death and here they enjoyed immortality and bliss. In the western part of the Mediterranean were giants, monsters, enchantresses. The dawn, Sun, Moon and stars rose out of the ocean in the east to sink into the ocean in the west.[1]

In the 6th century BCE the idea of a spherical Earth is recorded, probably originating from the Pythagorean School of philosophy. And then in about 240 BCE Eratosthenes Greek mathematician, geographer and chief librarian in Alexandria calculated the circumference of the Earth to within 5-15% of present-day figures, he also calculated the tilt of the Earth’s axis, and a fairly accurate stab at the distance between the Earth and Sun. That planet Earth was a sphere was not conclusively demonstrated until the first world circumnavigation by Portuguese sailor Ferdinand Magellan in the years 1519 to 1521 (he did not survive the voyage himself).

However, only 600 years ago the world was still a place containing distant lands of unknown wonders and terrors: we had little idea of the Earth itself let alone the universe although it was always assumed that humanity was at its centre. Our knowledge of the character of space in the universe has likewise undergone drastic recent change. Ancient Greeks would have been dumbfounded by the knowledge that today we calculate the distance between objects in space using the speed of light as a unit of measurement.

In February 2016 scientists from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatories (LIGO) in Louisiana and Washington announced the discovery of gravity waves as a consequence of the collision of two black holes. This discovery means that we can now investigate space through a medium other than light using an instrument so sensitive that it could detect a change in the distance between the solar system and the nearest star four light years away to the thickness of a human hair. So far we have observed the universe mostly using light. This confines our vision to only part of what happens in the universe. Gravitational waves carry completely different information about phenomena in the universe. Using electromagnetic waves we cannot see further back than 400,000 years after the Big Bang as the early universe was opaque to light. It is not opaque to gravitational waves so we can now see exactly what happened at the initial singularity.

If you have doubts about science as a system of knowledge that can improve our understanding of our location within the universe then compare the Greek vision of the known universe of 850 BCE with that of September 2014 (http://www.nature.com/news/earth-s-new-address-solar-system-milky-way-laniakea-1.15819) and the revelation of February 2016.

Time

Chronometric Revolution

There has, since WWII, been a little-acknowledged Chronometric Revolution ‘ … at the end of the nineteenth century it was still impossible to assign reliable absolute dates to any events before the appearance of the first written records’ but ‘There now exist no serious intellectual or scientific or philosophical barriers to a broad unification of historical scholarship’ as improved dating techniques have brought science much closer to mainstream academic history. We can now date (sometimes with great precision): the age of the universe and atronomical phenomena, individual rocks and fossils, archaeological remains, and the timing of the divergence of lineages in biological evolution (see Big history for details).

In the early 1800s European geology was still extricating itself from Deluvianism, the biblical story God’s Creation as told in Genesis notably the great flood, and Noah’s ark. James Ussher (1581-1656) Archbishop of Ireland had established a biblical time-frame by dating the Creation to 4004 BC and this was widely believed. One school of thought, Neptunism, held that rocks were formed as strata settling out in water by sedimentation, the oldest being granite while newer layers contained fossils as a result of further flooding. In contrast Plutonism (Vulcanism), held that rocks were formed in fire, eroded by weathering and then re-formed and uplifted under heat and pressure, the whole process taking eons of time rather than the thousands of years assumed by biblical time-frames. First hints of modern geology came when Frenchman George-Louis Leclerc, Compte de Buffon (1707-1788) Director of the Jardin du Roi in Paris who hypothesised that the Earth began as a hot, fiery ball of molten rock consisting mostly of iron and Scottish geologist James Hutton (1726-1797) who began to seriously question the biblical figures followed by British geologist William Smith (1769–1839) who observed different rock strata having distinct types of fossils. Even so it was only in the early 19th century that geology began to shake off a literal interpretation of the bible and take on its modern form – although there had long been an acceptance of three major human phases of history based on the technological phases of stone, bronze, and iron. It is easy to forget that up to the early 19th century there was no theory of evolution. Modern geology had not been born (the Earth being considered a creation of God only a few thousand years old with fossils placed within geological strata by God himself). Most people were illiterate and there was almost universal belief in special creation.

Research in anthropology and other subjects now allows us to roughly date the origin and evolution of life on Earth about 3.5 billion years ago, the emergence of the genus Homo about 2 million years ago, the species Homo sapiens about 200,000 years ago and to trace a rough path of migration of modern humans as they walked out of Africa about 60,000 years ago to inhabit all continents.

Modern physics now tells us that our universe originated in the Big Bang 13.75 ± 0.11 billion years ago and it is currently both expanding and cooling. Until about the 1920s the universe was considered to be all a part of our galaxy, the Milky Way, of which the Solar System was one small part. We now know that the observable universe consists of a ‘cosmic web’ of about 170 billion galaxies. The universe is expanding rapidly and we only see the stars and galaxies whose light has had time to reach us, the number of these receding as space expands. Measurements of the observable universe’s geometry suggest that it is a flat disc (amazingly like the Earth disc postulated by ancient civilizations).

The Earth and Sun are about five billion years old, being formed at roughly the same time as the other planets in our solar system. In three to five billion years the Sun will swell to become a Red Giant, engulfing the Earth as it does so.

Currently the galaxies are moving apart at an ever-increasing rate. The ultimate fate of the universe depends on uncertain factors such as its shape and role of dark matter which is currently under research. The ‘Big Rip’ theory suggests the expanding universe will disintegrate into unbound elementary particles and radiation; the ‘Big Crunch’ claims that current expansion will reverse and a callapse ensue, leading to a dimensionless singularity. Perhaps there is a continuous repeated cycle of ‘Big Bang’ followed by ‘Big Crunch’, a scenario described as the ‘Big Bounce’. However, there is a growing consensus among cosmologists that the universe is flat and gravitational forces are insufficient for it to contract again so it will continue to expand indefinitely, cooling as it does so until in 10 billion years the stars will have mostly burned out and faded until in about 100 billion years there will be universal darkness – what physicists refer to as the ‘Heat Death’ or ‘Big Freeze’ as the temperature approaches absolute zero and total darkness descends.

English-speaking people in the early nineteenth century seriously believed that the earth and universe were only a matter of a few thousands years old. Only seven generations ago we did not have the faintest idea of humanity’s place in time. Today we can comprehend the sweep of cosmic history dating with remarkable accuracy the origin of the universe, solar system, life, humans and much more. We can even make an educated guess at likely ways in which the future of the universe will play out.

Knowledge

Knowledge can take many forms but it has always been respected as a source of power. To know more is to have an advantage. A distinction is often drawn between descriptive (declarative or propositional knowledge – ‘know what’) expressed in declarative sentences or indicative propositions, and prescriptive (procedural – ‘know how’) knowledge as procedural knowledge, ‘knowing of’, or knowledge by acquaintance.

Limits to knowledge

Various attempts have been made to gather together in one place the totality of human knowledge. In the classical world we have the example of Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder and his monumental Naturalis Historia consisting of 37 books divided into 10 volumes and this was to serve as a template for the later encyclopaedists. Theologians of the Middle Ages also felt the need to synthesise religious knowledge, one major publication being the Summa Theologiae (1265-1274) of Thomas Aquinas. The attempt to capture the whole order of nature, or to depict the entire world or universe, was sometimes referred to as cosmography. English cleric Peter Heylin (1599–1662) of Oxford University was a specialist in historical geography and in 1657 he wrote the book Cosmographie which was an elaboration of his earlier Microcosmos (1621). This was the most comprehensive English seventeenth-century geographic description of the known world and it included what is perhaps the first known description of Australia as well as an early description of California. This was followed in 1659 by the Compendious Description of the Whole World written by Thomas Porter which included a chronology of world events starting with the Creation.

The number of synthesisers was to increase rapidly with the spread and improvement of printing, among the better known being explorer-scientist Alexander von Humboldt and his five-volume biogeographic tract Kosmos (1845). With the revival of classical learning during the Western Enlightenment and Renaissance grand syntheses of human knowledge were produced in vast encyclopaedias like the 27 folio volume Encyclopedie (1772) of the French Enlightenment figure Denis Diderot (1713-1784). No doubt part of the stimulus for such works was the discovery of new lands and the realisation that the Earth had finite bounds that could be mapped and thoroughly explored. Arguably this was also a time when well-educated gentlemen could have a general grasp the entire breadth of human knowledge, something that is unimaginable today.

Wikipedia is a good example of today’s communal desire to accumulate all human knowledge in one place (5,730,603 on 9 Oct 2018), and perhaps Big History has taken the place of the older cosmographies.

Factual knowledge, it seems, has simply accumulated over time, the pace gathering momentum assisted by major historical technological advances that have facilitated its transmission and storage: writing, printing, and electronic data. Having vast numbers of facts at our fingertips must surely create a world of greater choice – but not necessarily greater wisdom in the exercise of that choice.

There is some evidence that knowledge accumulation can be like the search for gold or oil – that ideas are getting harder to find. Just as the popular concerns of morality (animal rights, sexual liberation) are seemingly taking on a finer resolution, so more scientists and resources are needed to achieve the same productivity goals.

Value

How is everything in the world related & what is important to me? The Great Chain of Being

How are we to rank, value and categorise everything around us – where does everything fit in relation to everything else?

At the time of British settlement of Australia the grand narrative of Christianity was beginning to accommodate the grand narrative of science that had been gathering momentum during the Renaissance and Enlightenment. However, the European settler view of the world would have been a Christian cosmology that embraced some variant of the Great Chain of Being. The Great Chain of Being was a highly influential grand narrative of European society that still has many echoes in social and scientific Western thinking. The scala naturae or Great Chain of Being, is an idea derived from antiquity, espoused by Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle (PAiv.5,681a10-15, PAiv.10,686b21-687a4, HA viii.1, 588b12-22), and later modified by the Neoplatonists and Christianity, although elements of this view occur in other cultures and religions.

In very general terms everything in existence was asssumed to be organised (and classified) into a continuous hierarchy arranged in a linear and graded order like the rungs of a ladder, but in degrees of perfection. In the material world there were rocks at the bottom, plants a little higher, followed by animals then, at its pinnacle, human beings. Each rung of the ladder (including species) was eternal and immutable as created by God (although alchemy presented the mesmerizing possibility of converting a base metal to gold). In Christianity a spiritual dimension was included called the ‘soul’ which first appears at the level of humans (animals did not have souls but angels did). The entire edifice of existence was overtopped by the creator God in heaven who was not physical but pure spirit – omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent, transcendent, eternal, and perfect – while at the bottom, in a spiritual underworld, there was the devil and fires of hell.

The Ladder of Life communicated a vision of the world that was assumed to be fixed and real, not a product of the human imagination: it was a framework or structure through which to understand the messy complexity of ‘everything’. This world was organised from ‘lower’ to ‘higher’, from material to spiritual, from imperfect to perfect, from irrational to rational, from simple to complex. Everything had a fixed place in the timeless natural order. To challenge this hierarchy was futile; it was simply the way the world was structured. For most people this was the way the world had been created by God – and therefore the way it would stay. The task of humans was to become more spiritual and less material, to release the human soul from its prison of matter. On Plato’s reading in the Timaeus humans were a microcosm of the greater macrocosm, both organized under similar principles: the orderly behaviour of the heavens signalled the need to govern our individual and collective lives in a rational way.

Hierarchy

Our everyday language is infused with the ideas of the past. One probable carry-over from Aristotle’s scala naturae is the metaphorical language that ranks ideas by altitude, to ‘levels’ that are ‘higher’ or ‘lower’. Hierarchy is deeply embedded in our language and thinking when we speak metaphorically of the ‘rise’ and ‘fall’ of nations, of ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ organisms, of a ‘social ladder’, ‘glass ceiling’, ‘top dog’, ‘high achievement’, ‘low-life’, ‘middle management’. When we take the time to think about the many ways that hierarchy appears in our daily conversations then we can quickly see how it can subtly structure the way we perceive the world.

Colourful metaphors add interest to communication and we are well aware that the idea of some sort of moral or physical altitude is just a figure of speech. But hierarchical language can still carry a moral loading – an attached value. It is more informative to speak of complex and less complex organisms, rather than ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ organisms, if that is what we mean. In fact we would undoubtedly communicate more clearly without metaphorical hierarchies.

The social order

Are social hierarchies the inevitable consequence of a need to maintain social order? How are people to be ranked and organised – which people should have power and authority over others and why?

Animals develop hierarchies that are always the same within a species and therefore clearly based on biological factors. Humans, in contrast, have devised hierarchies based on many different factors. Even so, moral psychologists point out that hierarchical sentiments related to loyalty and submission may have some innate foundation. How are we to behave towards one-another when the different hierarchies of different societies meet?

Humans too have displayed strong social hierarchies with some people and races higher up the ‘social ladder’ than others. Even within particular societies the organization into different classes was not regarded as simply a practical and convenient way of ordering society, the ‘upper’ classes – priests, aristocracy, kings and rulers were generally regarded (implicitly if not explicitly) as ‘higher’ or ‘better’ in a moral or absolute sense than the lower groups or castes and occasionally, as with some Roman Emperors, humans would claim the status of gods.

The natural order?

Throughout history great philosophers and religions have acknowledged the Golden Rule Do as you would be done by as the rational recognition that no individual can reasonably privilege themselves over another. However, this principle of equality is challenged by our real-life differences. Social hierarchies are based on many factors including physical and intellectual difference, religion, race, wealth, gender, caste, occupation, blood line, role in society, or historical tradition. Hierarchies create social order and often reinforced by being considered part of a biological (natural) or religious cosmic order and therefore not to be challenged. Sometimes it is simply more convenient to interact with people according to a social category rather than as individuals on their own merit. Hoiwever, such categories can be taken as the measure of intrinsic worth. A major challenge for future generations is to establish social hierarchies that are as fair as possible and where power of one group or person over another is not abused. Part of this process involves coming to an understanding of the historical circumstances and reasons why such hierarchies arose and what justification exists for their continuation.

Racial & class arrogance

At the time when European colonization was at its peak, and while the British empire flourished, it was generally assumed that white Europeans were at the top of the human hierarchy. Following in a long tradition but derived mainly from the classicalworld, Britain was divided into classes, the landed and wealthy gentry, nobility, and royalty were the natural rulers. Representation in social decision-making (parliament) was decided by sex (males only) and wealth. Gentlemen were accustomed to servants and servant obedience. Well-to-do scientists like Banks and Darwin had manservants wherever they went, including their scientific voyages around the world.

Discipline & the law

Gentleman of the aristocracy were not necessarily oppressors, they too were locked into a system which they did not necessarily support or approve. However, the apparent injustice of such a system of privilege was a major factor in the European revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries and the need to maintain social order could give rise to terrible abuse. This was clearly exposed at sea. Sea captains (generally members of the upper classes in all European navies) would resort to extremes of physical punishment to subdue any undesirable behavior and it included: flogging, keel-hauling, walking the plank, and hanging from the yard-arm (a sail spar), all formally witnessed by the entire crew as a deterrent. The most popular of these was flogging in which the bare back was thrashed with a cat-o-nine-tails (a whip with nine lead-studded leather thongs) salt being rubbed into the lacerations when the punishment was complete. Offenders who lost consciousness were revived with a bucket of water and the process continued. Keel-hauling entailed tying the offender to a rope that looped on both sides of the ship, the offender jumping off the back or side of the ship and his crew-mates pulling on the two ropes to carry him under water along or across the ship’s keel: it was almost certain death.

The European assumption, at the time of settlement of Aboriginal Australian, was that Europeans were superior to Aborigines. This was clearly not just because Europeans had more complex technology, more effective weapons and the like – they felt themselves superior and more civilized in an absolute moral sense. They considered themselves ‘higher’ on the Great Chain of Being and they spoke of ‘moral education’ and the ‘civilizing’ influence that agriculture would have on stone age savages and how agriculture was a higher stage of being than the lowest stage – which was to be a hunter-gatherer.

Ideas that were abandoned by Western science nearly 200 years ago still cloud our judgment. The belief that humans are, in some absolute sense, superior to other organisms (speciesism), and that some humans are superior to other humans is still part of what might be called the Western grand narrative. Ideas of this broad kind underpinned the spread of Empire and the global Western society that we live in today. It was only in the early part of the twentieth century, after the Second World War that, in Britain, the ‘upstairs-downstairs’, ‘upper class, middle class, lower class’ social hierarchy began to break down.

Gender

Almost all societies, at least since the agricultural revolution, have been patriarchal, men privileged over women and dominating the economic, political and legal systems. For much of history, and across cultures, females were treated as male property to treat at will. Hence in almost all countries, up until recent times, rape of a wife was simply not possible – it was a right linked to the woman being property. Why should this apparently universal phenomenon have occurred? Has this hierarchy arisen through historical circumstance and/or biological difference?

Child-rearing

Certainly child-bearing and child care are biologically based but the culturally sanctioned denial of a place for women in political and civic life appears culturally sanctioned since women do not lack intelligence or political skills.

Physical strength

Men are certainly physically stronger and dominate the economic world in a way that translates into political power. But strength is not universal and women have more stamina. More importantly there is no connection between political ability and physical attributes because social power depends on social skills, not physical strength. Traditionally it has been the physically strong that have done the manual work, not the political negotiation with its dependence on social skills.

Aggressiveness

Are males more aggressive and willing to engage in physical conflict? Are men more competitive and do they compete more for partners? Certainly there are hormonal differences between the sexes and men are indeed more violent, but again this does not translate directly to efficient use of political power when women appear to have the necessary skills.

Perhaps men are more competitive , one example maybe being their competition for women? Perhaps women needed men to care for them during and immediately after pregnancy and this resulted in submissiveness? But it is possible to depend on other women. Female social networking teaches negotiation and compromise while these male skills remain undeveloped (this occurs in bands of bonobos).

There is no clear answer.

The biological order

The Great Chain of Being (or versions of it) were increasingly challenged during the Renaissance and Enlightenment as science and secular ideas strengthened.

Botanists were among the first to accept that, although there were differing degrees of structural complexity in plants, it did not make sense to give pride of place to some over others because they were in some way more ‘perfect’ or ‘higher’ in a Great Chain of Being. During the Reformation many botanists were influenced taxonomically by the idea of giving equal weight to each individual in parallel with the view of human equality in the sight of God in a personal relationship that was not mediated by priests of the Church.[8] Zoologists took longer to convince but when, in 1817, the internationally respected French zoologist Cuvier published his authoritative classification of animals, Le Règne Animal, he did so acknowledging Aristotle as predecessor. However, he ranked the animal kingdom on the basis of anatomy (not status within the Great Chain of Being) devising four great groups: the Vertebrata, Articulata, Mollusca and Radiata – ‘It formed no part of my design to arrange the animated tribes according to perceived superiority‘. No group was inherently superior to any other: degrees of perfection were irrelevant. Organisms were simply different – more or less complex, yes; some better adapted to their environments than others, maybe – but not ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ in some cosmic absolute, moral or religious sense. This point may seem obvious today but we can still make quick false assumptions. A chimpanzee is not a failed human, a rather pathetic animal on the evolutionary path to a better life as a human, instead it is an animal that has evolved by adapting to its own particular environment in its own particular way.

The Postmodern metanarrative & science wars – by what authority?

There are no facts, only interpretations

Friedrich Nietzsche

Post-modernism (a panchretic label) of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries questions the validity of all metanarratives but especially modernist certainty and its confidence in scientific objectivity. As a form of skepticism it challenges the claim that we can study the world in a neutral way, observing reality and truth by using the power of reason and science: it questions the notion of certain knowledge and also its value. By what authority can any interpretation take precedence over any other, whether it is an interpretation of history, literature, art or science? Science, like all other grand narratives, is perceived as an explanatory quicksand and just like all other grand narratives though seeming ‘real’ and ‘true’ right now will inevitably, in the future, be assessed correctly as simply a product of a particular time, place and circumstance. We create our own truth and our own meaning: neutral, absolute or objective knowledge is illusory. Any claims to ‘truth’ are simply ways of exerting power and influence of various kinds – truth is simply what works for us, or what we can persuade others to believe. Through most of history we have been told what to believe. Control of the societal grand narrative, once in the hands of a priestly class has passed in part across to humanists, secular scientists, and the intelligentsia of the day. Today there seems to be a mix of these – although some might claim that it is now the world view of economists that prevails.

So postmodernism regards metanarratives (statements about science, history or literature) as legitimations or prescriptions of specific versions of the ‘truth’ – simply narratives (stories or myths) that reflect the culturally embedded viewpoint or conceptual framework of the narrator. Metanarratives are created and reinforced by power structures, they may serve Utopian ideals and tend to dismiss the naturally existing chaotic variety of experience. Metanarratives may be used to reinforce dogma, examples being Marxist theory of historical development, unwarranted presumptions about the meaning of life (religions), or prescribed goals for human activity. There is no grand-narrative other than the one we happen to adopt as individuals or communities acting within a particular cultural context: the diversity of human aspiration and experience is a demonstration of the inevitable variety of grand narratives. Postmodernism as a program offers ‘deconstruction’ as a means of making underlying agendas self-evident. In the absence of an absolute truth aren’t we left with some kind of relativism where, say, accepted standards become purely relative to a particular culture or language?

Critics of postmodernism point out that postmodernism is itself a grand narrative using the tools it attacks to make its case. As a universal skepticism it must confront its own criteria as a self-refuting grand narrative – like the liar who says ‘This statement is false’. It uses logic, reason and other theoretical tools to make its case against these things themselves.

So what can we believe as having any validity or truth? We could accept living with a variety of legitimated language games – a multiplicity of interpretations each equally valid rather than a single, monolithic and all-encompassing theory.

But what if these ‘relative’ truths conflict? Our vision of reality (even the scientific vision) can only be a reflection of our subjective nature and thought processes.

For those who value the scientific and Enlightenment mode of thought both religion (God ultimately controls everything going on in the universe) and postmodernism (there can be no such thing as ‘truth’) rob people of any individual self-initiated impetus for action. When considering cases like climate change and the construction of nuclear bombs, it does not seem to be helpful to argue that scientific knowledge is a social construct. Post-modernism seems not to understand the underlying skepticism of science and to overestimate its claim to certain knowledge. Science may not be truth but regarding it as just modern myth is simply mistaken (see also The grand narrative of science and Reason & science).

Spirit

Much of the spirit world of the past: its ghosts, ghouls, poltergeists, magic, charms, angels, spirits, elves, devils, leprechauns and multiple deities have been discarded. Even so, the majority of people on Earth believe in some kind of supernatural or spirit world that cannot be accessed by science but only by faith and feeling of inner certainty.

A world without God

Politically the West has accommodated multiple religions by separating the powers of the Church and State in a process of secularisation. However, because for many people God is the source of value, meaning, purpose and, above all, moral direction, then God’s absence (and the absence of absolute values in general) may be unthinkable. A world below us (the underworld) or above us (heaven) serves the important function of making right the injustices of this world, a place where earthly ethical scores can be finally settled.

For some people the absence of God is a release. Philosophers like Friedrich Nietsche and existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre have pointed out that that the absence of God does not produce a moral vacuum but instead places full moral responsibility on us as individuals unaided by any divinely ordained rules of behaviour.

Modern culture is still struggles in its adjustment to religious diversity.

The edifice of science

See also Reason and science and The grand narrative of science

Evidence-based science and the scientific method gathered momentum during the Enlightenment. When Darwin first proposed his theory of descent with modification he was regarded by the community at large as a crackpot. Cartoons appeared in the popular press lampooning his insulting idea that humans were related to apes. But hard evidence in support of his ideas continued to appear until, by 1870, Darwin’s theory was broadly accepted by the scientific community, although natural selection as its mechanism remained in question. With mounting evidence it became clear that a literal interpretation of the bible must be discarded by all but the most stalwart believers. Religion had to find ways to accommodate science, not vice-versa as had previously been the case. Darwin’s theory was reaching towards a scientific grand narrative as part of a process of secularization that had been under way for some time.

Matter

Limitations of science

Certainly science has a social dimension that influences the topics researched and the manner in which its assertions come to be accepted by the scientific community[1]; the ‘truths’ of science have become modified over time as additional evidence has emerged or explanations become more all-embracing; there is an element of probability about many scientific conclusions, and scientists are always challenging the ‘truth’ of their theories.

All these factors can give the impression of relative truths with shaky and shifting foundations – facts that change. In spite of all this we demonstrate our trust in the scientific method, scientific knowledge and its system of principles and laws whenever we watch television, use our mobile phones, visit the doctor, fly in an aeroplane, or worry about the use of nuclear weapons. The evidence and principles on which such matters depend is clearly not just another myth or story among many others, just ‘real’ in the way that a dream is real while it lasts, or the way an artistic fashion is simply a product of a particular place and time. Ancient Greeks believed that dawn occurred when, each day, Apollo with his horse and chariot drew the Sun out of the sea and across the sky: today we really do know ‘better’ not just ‘different’.

Though we can achieve much with our creative imaginations we cannot directly alter the ‘physical world’: we might be able to convince ourselves of all manner of things but we cannot focus our mind to change a tree into a house, bend spoons, or live forever. Both ourselves and the objects in the physical universe are subject to factors (scientific ‘laws’) that are outside their control. In spite of all its shortcomings science is our most reliable source of ‘truth’: evidence based knowledge that constantly seeks to proves itself wrong, it is postmodern skepticism but basing its conclusions on the best evidence available.

Historical narratives

Of course our view of the world and the future is coloured by factors other than science, religion and culture. Our assumptions about progress and the ‘rise’ and ‘fall’ of nations and groups, however well founded, can lead to over-simplistic historical analyses of ‘success’ and ‘failure’, the view that history is all about ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ based largely on restrictive assumptions concerning technology or economics.

Today we might draw attention to two competing views that are more attitudinal than ideological – one of optimism and one of pessimism; one triumphal, one Apocalyptic. The fact that opinions diverge like this may be a matter of our differing values, often expressed as either anti-business alarmism or pro-growth greenwash. But such extremes can be informed by improving factual evidence.

Mind

For much of human history the mind was regarded as a spirit-like phenomenon that was distinct from matter: it could exist separately from the body and exist in a separate domain (see Purpose – Aristotle to Darwin). Philosopher Descartes posed the stark contrast of body and mind as separate entities. The mind, and especially consciousness, remain controversial, its association with matter still being problematic although we assume that consciousness is in some way a product of the configuration of neural networks since there is no compelling evidence of mind in any other contexts. These matters are discussed elsewhere.

Do we have a modern grand narrative?

Coming to grips with today’s world involves the complex assessment of our views on reality, meaning, purpose, science, progress, and much more. When confronted by complexity and conflicting evidence we have no choice but to follow our intuitions, what our minds tell us. The following two extreme positions are offered as an expression of modern intuitions about the world that call for some resolution based on improving factual evidence.

Optimism

For the positive triumphalist the story of humanity is, despite setbacks, one of human resourcefulness, enterprise, achievement and progress. This optimistic outlook has been called ‘the Whig view of history’. Through determination, endurance and creative imagination, humanity has overcome adversity to survive and prosper leaving a proud history of achievement including artistic, intellectual, cultural, political, social, technological, and economic advances that could hardly have been imagined just a few generations ago. We have placed men on the moon, discovered the mysteries of matter, space and time, split the atom, and unlocked the secrets of the genetic code. We have built stable and humane forms of government and economics, and reduced violence. We have extended life-expectancy globally and nationally, improved education and literacy and made major inroads in the battle with poverty.

Globalisation now fosters cooperative economic growth which will eventually eliminate poverty and, when combined with technology and human creativity, also improve both our global environment and material well-being.

In general, people today are happier and better off than those who lived in the Middle Ages, who were themselves better off and happier than Neolithic farmers who, in turn, were much happier than Stone Age hunter-gatherers. Given no natural disaster we should be able to harness technology, the invisible hand of the market, and positive human willpower to create a bright, stable, and more harmonious future.

Pessimism

An apocalyptic negative view suggests that the agricultural Neolithic Revolution marked the first severance – both a physical and psychological separation – of humanity from the natural world. This disconnection from nature has led to the present-day indifference to environmental degradation that is going on around us together with the souless inhumanity of industrialization, advertising, consumerism, and product fetishism. The development of cities, city-states and nations has created wage-slavery and the subjugation inherent in social hierarchies, along with the arrogance and misery that accompanies empires and colonial exploitation. Today an escalating and high-consumption human population lives in artificial environments (artificial lighting, heating, cooling, and the virtual realities provided by technology) while depleting natural resources, increasing numerically, and consuming uncontrollably and unsustainably, polluting the environment while creating an increasing social divide between rich and poor. When once people were actively engaged with nature or farming in the open air, most people in the West today are unaware of how their food is grown or where it comes from: they have escaped into a world of computers, smart phones, and televisions. Psychologically and physically this may be comfortable, but it takes us further away from our evolutionary origins, panders to greed, materialism and selfishness, spawns events like the global financial crisis, and an indifference to the natural world that is our life-support system. This is a detachment and indifference that is threatening the future of humans on planet Earth our inability to react to the realities of climate change being just one symptom among many.

We have now created global environmental problems that are sowing the seeds of our own demise, the product of socio-economic institutions of our own creation that are growing inexorably out of control as we step over more and more non-returnable planetary boundaries. The only possible way forward is to reject economic growth and create a global green economy that operates within the Earth’s ecological limits.

One of the major tasks for the present generation is to evaluate the evidence for these two apparently contradictory outlooks on the world so that there may be a more consensual vision for the future that is based less on sentiment and more on evidence.[9]

Commentary & sustainability analysis

We need the best possible system to manage the planet to optimize the flourishing of humanity and the community of life. But how do we negotiate the many different values we hold dear according to our race, religion, political ideology, local interests and so on?

Each one of us employs a grand narratives to help us understand and explain the mysteries of life and death, the meaning of our existence, and our place in society and the world.

As our world becomes progressively more interconnected and interdependent the reconciliation of differing grand narratives becomes more pressing. Today’s confrontation of diverse grand narratives has some resemblance to the advent of monotheistic religions during the Axial Age as a way of dealing with the logical absurdity of multiple spiritual realities, moral codes, and belief systems. Today too we must overcome the surely arrogant notion that one view must be ‘right’. We must surely try and live with tolerance: difference of opinion may lead to fervent debate but need not result in violence and bloodshed.

We encourage peaceful coexistence through time-honoured strategies including: improving social interaction and interdependence by engaging in trade and commerce; the formal establishment of internationally accepted systems of behaviour and law; an increasing exchange of ideas and promotion of cosmopolitanism aided by the use of all communications media including social media; and, arguably, the encouragement of liberal democracy. Such approaches, we hope, will encourage greater mutual tolerance by avoiding the view that a meeting of differing grand narratives means that someone must prevail.

For the student there is the apolitical and intellectual process of examining the nature of grand narratives as part of the global meeting of cultures, religions, value-systems, languages, and ideas.

Does science give us an increasingly accurate view of the world? Is it possible, for example, for the various religions to find common ground? In what ways, if any, is science in conflict with religion? What can we do to facilitate mutual respect when people with vastly different grand narratives meet and interact? Can one grand narrative be right and another wrong and whatare the consequences of this? How are we to deal with logical inconsistencies between grand narratives? Can anyone claim to be in posession of absolute truth? If someone firmly believes they are in possession of absolute truth how do they reconcile this view with that of someone who believes they are in possession of a different absolute truth? What sort of truth can science offer? In what ways, if any, are science and religion related? Do humans have some genetic predisposition to religious belief or grand explanations?

More than any other factors the grand narrative of science has drawn our attention to the fact that space and time are the ultimate finite resources; a fact that has only emerged with genuine urgency in the last fifty or so years.

In trying to understand the world we use all kinds of categories (see Reason & rationality) whether they be names, theories, definitions, explanations, laws or whatever. Among the most important categories we use are those that set boundaries or limits to large blocks of our world, that is, ones that encompass many others. Those that claim to deal with absolutely everything we call a grand narrative, like a religious account of the world. But there are lesser grand narratives that might circumscribe, for example, the limits to the physical world – or what it is possible for us to think, understand, know, say or do.

Clearly grand narratives are of such importance that we need to understand them as best we can. Who or what is it that is setting the boundaries? What evidence is there for both the agents controlling the boundaries and for the authenticity of the boundaries themselves?

Perhaps there is much to be learned about our minds themselves through the way be categorise the world – creating or imposing boundaries where non actually exist and missing others, or choosing ones that could be located more beneficially somewhere else? Maybe our inability to comprehend infinity is simply a function of the way our minds which as evolved structures impose boundaries on everything we think about?

Grand narratives serve different needs. For those requiring an understanding of the material world around them the power of scientific explanation and its application through technology is as convincing and reliable source of knowledge as we can muster. Though science, like other disciplines, is based on theories and changing hypotheses about the world and its material contents (see Grand narrative of science) its self-evident ‘reality’ is overwhelming – whether we use it to travel into space, manipulate our genetic makeup, create modern medicines, or build weapons of war. Science gives us a compelling explanation of the universe and its fundamental constituents, the origin of and evolution of life, the physical location of humanity within the universe, and the physical boundaries of our existence.

This leaves us with spiritual and ethical grand narratives. Somehow we must track a course through these difficult seas. Here is a task for future students of the grand narrative. Perhaps this is a field for multidisciplinary research for those who are experts in myth, religion and ethical systems. How are we to deal with grand narratives that are in apparent conflict? How are we to understand and manage moral and spiritual certitude? Is it possible or desireable, in the face of divergent narratives, to establish a new metanarrative that is mutually acceptable to all?

This web site is a contribution to this discussion as it delves into human nature, moral systems, and the possibility of a globally unified program for human sustainability on planet earth.

Key points

- Grand narratives explain how and why the world arose and the role of humans in it

- Grand narratives are used to legitimate social and other structures

- Having a grand narrative is a universal characteristic of human society: it simply does not seem possible to ‘not know’

- Lesser grand narratives can describe subsets of this larger picture like – how everything is distributed in space (geography and cosmology); how everthing played out in time (cosmology); how humans have interacted over time (world history, Big History); everything there is (descriptive science); how everything is to be ranked and ordered (taxonomy and the Great Chain of Being); how and why large human groups (countries and societies) are to be structured

- The grand grand narratives of today remain science and religion, sometimes viewed as challenged by economics or postmodernism

- Until about the mid nineteenth century (the publication of Darwin’s Origin… and realization of the vast temporal and spatial extent of the Earth and universe, dwarfing the period of inhabitance by humans and later confirming genetic continuity between humans and all other life), cosmologies were almost exclusively anthropocentric humanity considering itself the essence, meaning, and reason for the cosmos

- Today’s Western grand narrative can be influenced by optimism and pessimism with realism requiring improvement of the evidential base

*—

First published on the internet – 1 March 2019